Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma with Prominent Expansion of PD-1+ T-Follicular Helper Cells: A Persistent Diagnostic Challenge with a Heterogeneous Mutational Architecture

Abstract

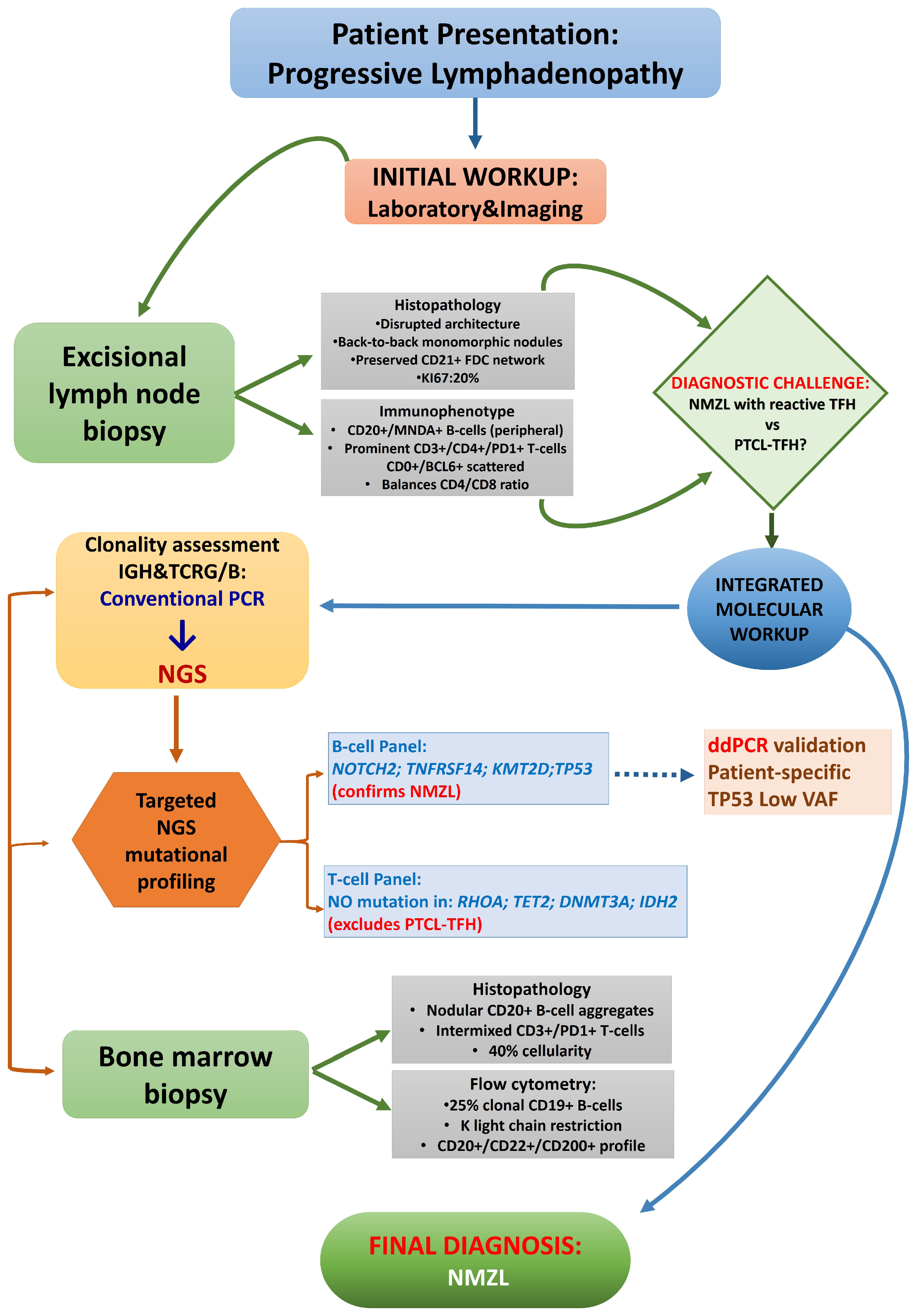

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Case Summary

2.2. Histopathological and Immunophenotypic Findings

2.3. Molecular Genetic Findings

2.3.1. Clonality Assessment

2.3.2. Mutational Profiling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

4.2. DNA Isolation and Quality Control

4.3. Clonality Assessment

4.4. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

4.5. Droplet Digital PCR

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zucca, E.; Arcaini, L.; Buske, C.; Johnson, P.W.; Ponzoni, M.; Raderer, M.; Ricardi, U.; Salar, A.; Stamatopoulos, K.; Thieblemont, C.; et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 17–29, Correction in Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, C.; Bertoni, F. The Biology of MZL subtypes: Challenge and Relevance of Classification. Blood 2025, 30, blood.2024028268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo, I.B.O.; Berti, E.; Bhagat, G.; Borges, A.M.; Boyer, D.; Calaminici, M.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748, Correction in Leukemia 2023, 37, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, E.; Jaffe, E.S.; Cook, J.R.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Swerdlow, S.H.; Anderson, K.C.; Brousset, P.; Cerroni, L.; de Leval, L.; Dirnhofer, S.; et al. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: A report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood 2022, 140, 1229–1253, Erratum in Blood 2023, 141, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Martino, G.; Lazzi, S. A comparison of the International Consensus and 5th World Health Organization classifications of mature B-cell lymphomas. Leukemia 2023, 37, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, S.M. Marginal Zone Lymphoma: Treatment Update with a Focus on Systemic Approaches. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 43, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Bertoni, F.; Zucca, E. Marginal-Zone Lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, C.Y.; Zucca, E.; Rossi, D.; Habermann, T.M. Marginal zone lymphoma: Present status and future perspectives. Haematologica 2022, 107, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Kang, K.; Liu, Q.; Luo, R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, A.; Niu, T. Transformation risk and associated survival outcome of marginal zone lymphoma: A nationwide study. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 4211–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, A.G.; Caimi, P.F.; Fu, P.; Massoud, M.R.; Meyerson, H.; Hsi, E.D.; Mansur, D.B.; Cherian, S.; Cooper, B.W.; De Lima, M.J.; et al. Dual institution experience of nodal marginal zone lymphoma reveals excellent long-term outcomes in the rituximab era. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcaini, L.; Bommier, C.; Alderuccio, J.P.; Merli, M.; Fabbri, N.; Nizzoli, M.E.; Maurer, M.J.; Tarantino, V.; Ferrero, S.; Rattotti, S.; et al. Marginal zone lymphoma international prognostic index: A unifying prognostic index for marginal zone lymphomas requiring systemic treatment. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N.; Chen, X.; Zhong, Q.; Qiao, C.; Jin, H.; Li, J.; Fan, L.; et al. CD180 as a Robust Immunophenotypic Marker for Differentiating Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma/Waldenström Macroglobulinemia From Marginal Zone Lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 2025, 38, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, E.; Miquel, R.; Krenacs, L.; Sorbara, L.; Raffeld, M.; Jaffe, E.S. Primary nodal marginal zone lymphomas of splenic and MALT type. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999, 23, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bob, R.; Falini, B.; Marafioti, T.; Paterson, J.C.; Pileri, S.; Stein, H. Nodal reactive and neoplastic proliferation of monocytoid and marginal zone B cells: An immunoarchitectural and molecular study highlighting the relevance of IRTA1 and T-bet as positive markers. Histopathology 2013, 63, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, D.M.; Brown, J.A.; Shahsafaei, A.; Freeman, G.J. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) is a marker of germinal center-associated T cells and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leval, L.; Parrens, M.; Le Bras, F.; Jais, J.P.; Fataccioli, V.; Martin, A.; Lamant, L.; Delarue, R.; Berger, F.; Arbion, F.; et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is the most common T-cell lymphoma in two distinct French information data sets. Haematologica 2015, 100, e361–e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, C.; Laurent, C.; Alejo, J.C.; Pileri, S.; Campo, E.; Swerdlow, S.H.; Piris, M.; Chan, W.C.; Warnke, R.; Gascoyne, R.D.; et al. Expansion of PD1-positive T Cells in Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma: A Potential Diagnostic Pitfall. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Cao, Y.; Diao, X.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Shi, Y. Recognizing puzzling PD1 + infiltrates in marginal zone lymphoma by integrating clonal and mutational findings: Pitfalls in both nodal and transformed splenic cases. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamò, A.; van den Brand, M.; Climent, F.; de Leval, L.; Dirnhofer, S.; Leoncini, L.; Ng, S.B.; Ondrejka, S.L.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Soma, L.; et al. The many faces of nodal and splenic marginal zone lymphomas. A report of the 2022 EA4HP/SH lymphoma workshop. Virchows Arch. Correction in Virchows Arch. 2023, 483, 437. 2023, 483, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abukhiran, I.; Syrbu, S.I.; Holman, C.J. Markers of Follicular Helper T Cells Are Occasionally Expressed in T-Cell or Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma, and Atypical Paracortical HyperplasiaA Diagnostic Pitfall For T-Cell Lymphomas of T Follicular Helper Origin. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, S.N.; Caponetti, G.C.; Smith, L.; Qualtieri, J.; Morrissette, J.J.D.; Lee, W.S.; Frank, D.M.; Bagg, A. Mutational Analysis Reinforces the Diagnosis of Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma With Robust PD1-positive T-Cell Hyperplasia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 45, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langerak, A.W.; Groenen, P.J.; Brüggemann, M.; Beldjord, K.; Bellan, C.; Bonello, L.; Boone, E.; Carter, G.I.; Catherwood, M.; Davi, F.; et al. EuroClonality/BIOMED-2 guidelines for interpretation and reporting of Ig/TCR clonality testing in suspected lymphoproliferations. Leukemia 2012, 26, 2159–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, C.Y.; Seymour, J.F. Marginal zone lymphoma: 2023 update on diagnosis and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabzevari, A.; Ung, J.; Craig, J.W.; Jayappa, K.D.; Pal, I.; Feith, D.J.; Loughran, T.P., Jr.; O’Connor, O.A. Management of T-cell malignancies: Bench-to-bedside targeting of epigenetic biology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Bosch-Schips, J.; Gašljević, G.; van den Brand, M.; Balagué, O.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Ponzoni, M.; Cook, J.R.; Dirnhofer, S.; Sander, B.; et al. Exploring the boundaries between neoplastic and reactive lymphoproliferations: Lymphoid neoplasms with indolent behavior and clonal lymphoproliferations-a report of the 2024 EA4HP/SH lymphoma workshop. Virchows Arch. 2025, 487, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uherova, P.; Ross, C.W.; Finn, W.G.; Singleton, T.P.; Kansal, R.; Schnitzer, B. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma mimicking marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 2002, 15, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisig, B.; Savage, K.J.; De Leval, L. Pathobiology of nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas: Current understanding and future directions. Haematologica 2023, 108, 3227–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, N.; Choi, J.; Grothusen, G.; Kim, B.J.; Ren, D.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Inamdar, A.; Beer, T.; et al. DLBCL-associated NOTCH2 mutations escape ubiquitin-dependent degradation and promote chemoresistance. Blood 2023, 142, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Trifonov, V.; Fangazio, M.; Bruscaggin, A.; Rasi, S.; Spina, V.; Monti, S.; Vaisitti, T.; Arruga, F.; Famà, R.; et al. The coding genome of splenic marginal zone lymphoma: Activation of NOTCH2 and other pathways regulating marginal zone development. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.Q. EMZL at various sites: Learning from each other. Blood 2025, 145, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo-Ayala, F.; Béguelin, W. Biology as vulnerability in follicular lymphoma: Genetics, epigenetics, and immunogenetics. Blood 2025, 146, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobaño-López, C.; Araujo-Ayala, F.; Serrat, N.; Valero, J.G.; Pérez-Galán, P. Follicular Lymphoma Microenvironment: An Intricate Network Ready for Therapeutic Intervention. Cancers 2021, 13, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickenden, K.; Nawaz, N.; Mamand, S.; Kotecha, D.; Wilson, A.L.; Wagner, S.D.; Ahearne, M.J. PD1hi cells associate with clusters of proliferating B-cells in marginal zone lymphoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2018, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boice, M.; Salloum, D.; Mourcin, F.; Sanghvi, V.; Amin, R.; Oricchio, E.; Jiang, M.; Mottok, A.; Denis-Lagache, N.; Ciriello, G.; et al. Loss of the HVEM Tumor Suppressor in Lymphoma and Restoration by Modified CAR-T Cells. Cell 2016, 167, 405–418.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, S. T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity 2019, 50, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.J.; Johnson, N.A.; Affleck, J.G.; Severson, T.; Steidl, C.; Ben-Neriah, S.; Schein, J.; Morin, R.D.; Moore, R.; Shah, S.P.; et al. Acquired TNFRSF14 mutations in follicular lymphoma are associated with worse prognosis. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 9166–9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillonel, V.; Juskevicius, D.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Bodmer, A.; Zettl, A.; Jucker, D.; Dirnhofer, S.; Tzankov, A. High-throughput sequencing of nodal marginal zone lymphomas identifies recurrent BRAF mutations. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2412–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, V.; Khiabanian, H.; Messina, M.; Monti, S.; Cascione, L.; Bruscaggin, A.; Spaccarotella, E.; Holmes, A.B.; Arcaini, L.; Lucioni, M.; et al. The genetics of nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Blood 2016, 128, 1362–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, S.; Malcikova, J.; Radova, L.; Bonfiglio, S.; Cowland, J.B.; Brieghel, C.; Andersen, M.K.; Karypidou, M.; Biderman, B.; Doubek, M.; et al. Detection of clinically relevant variants in the TP53 gene below 10% allelic frequency: A multicenter study by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL. Hemasphere 2025, 9, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burack, W.R.; Li, H.; Adlowitz, D.; Spence, J.M.; Rimsza, L.M.; Shadman, M.; Spier, C.M.; Kaminski, M.S.; Leonard, J.P.; Leblanc, M.L. Subclonal TP53 mutations are frequent and predict resistance to radioimmunotherapy in follicular lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 5082–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araf, S.; Wang, J.; Korfi, K.; Pangault, C.; Kotsiou, E.; Rio-Machin, A.; Rahim, T.; Heward, J.; Clear, A.; Iqbal, S.; et al. Genomic profiling reveals spatial intra-tumor heterogeneity in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1261–1265, Correction in Leukemia 2019, 33, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lin, Y.; An, L. Genetic alterations and their prognostic impact in marginal zone lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela, V.; Juskevicius, D.; Dirnhofer, S.; Menter, T.; Tzankov, A. Mutational landscape of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of various origin: Organotypic alterations and diagnostic potential for assignment of organ origin. Virchows Arch. 2022, 480, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Feijóo Varela, R.; Lafuente, M.; Garcia-Gisbert, N.; Rodríguez, C.F.; Sánchez-González, B.; Gibert, J.; Ibarrondo, L.F.; Camacho, L.; Longarón, R.; Colomo, L. Genetic Characterization of Marginal Zone Lymphomas in Tissue and cfDNA. Blood 2024, 144, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.; Degeling, K.; Thompson, E.R.; Blombery, P.; Westerman, D.; IJzerman, M.J. Health economic evidence for the use of molecular biomarker tests in hematological malignancies: A systematic review. Eur. J. Haematol. 2022, 108, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Leval, L.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Bergsagel, P.L.; Campo, E.; Davies, A.; Dogan, A.; Fitzgibbon, J.; Horwitz, S.M.; Melnick, A.M.; Morice, W.G.; et al. Genomic profiling for clinical decision making in lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2022, 140, 2193–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sánchez-Beato, M.; Méndez, M.; Guirado, M.; Pedrosa, L.; Sequero, S.; Yanguas-Casás, N.; de la Cruz-Merino, L.; Gálvez, L.; Llanos, M.; García, J.F.; et al. A genetic profiling guideline to support diagnosis and clinical management of lymphomas. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 1043–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cappello, F.; Angerilli, V.; Munari, G.; Ceccon, C.; Sabbadin, M.; Pagni, F.; Fusco, N.; Malapelle, U.; Fassan, M. FFPE-Based NGS Approaches into Clinical Practice: The Limits of Glory from a Pathologist Viewpoint. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van den Brand, M.; Rijntjes, J.; Möbs, M.; Steinhilber, J.; van der Klift, M.Y.; Heezen, K.C.; Kroeze, L.I.; Reigl, T.; Porc, J.; Darzentas, N.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Clonality Assessment of Ig Gene Rearrangements: A Multicenter Validation Study by EuroClonality-NGS. J. Mol. Diagn 2021, 23, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wästerlid, T.; Cavelier, L.; Haferlach, C.; Konopleva, M.; Fröhling, S.; Östling, P.; Bullinger, L.; Fioretos, T.; Smedby, K.E. Application of precision medicine in clinical routine in haematology—Challenges and opportunities. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 292, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coccaro, N.; Tota, G.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Specchia, G.; Albano, F. Digital PCR: A Reliable Tool for Analyzing and Monitoring Hematologic Malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, S.H.; Erber, W.N.; Porwit, A.; Tomonaga, M.; Peterson, L.C. International Council for Standardization In Hematology. ICSH guidelines for the standardization of bone marrow specimens and reports. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2008, 30, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torlakovic, E.E.; Brynes, R.K.; Hyjek, E.; Lee, S.H.; Kreipe, H.; Kremer, M.; McKenna, R.; Sadahira, Y.; Tzankov, A.; Reis, M.; et al. ICSH guidelines for the standardization of bone marrow immunohistochemistry. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2015, 37, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggemann, M.; Kotrová, M.; Knecht, H.; Bartram, J.; Boudjogrha, M.; Bystry, V.; Fazio, G.; Froňková, E.; Giraud, M.; Grioni, A.; et al. Standardized next-generation sequencing of immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations for MRD marker identification in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; a EuroClonality-NGS validation study. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2241–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scheijen, B.; Meijers, R.W.J.; Rijntjes, J.; van der Klift, M.Y.; Möbs, M.; Steinhilber, J.; Reigl, T.; van den Brand, M.; Kotrová, M.; Ritter, J.M.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements for clonality assessment: A technical feasibility study by EuroClonality-NGS. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2227–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Lymph Node | Bone Marrow | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Reference Sequence Exons | Chromosome Position | cDNA Protein Mutation Type | VAF (%) | Gene Reference Sequence Exons | Chromosome Position | cDNA Protein Mutation Type | VAF (%) |

| NOTCH2 NM_024408 34 | 1 120458927 | c.6418C>T p.Gln2140* Nonsense | 5.7 | NOTCH2 NM_024408 34 | 1 120458927 | c.6418C>T p.Gln2140* Nonsense | 0.8 |

| TNFRSF14 NM_001297605 1 | 1 2488174 | c.69+2T>A p.? Splice Site | 7.3 | TNFRSF14 NM_001297605 1 | NDA | NDA | NDA |

| KMT2D NM_003482 19 | 12 49438688 | c.4801_4802delinsT p.Arg1601Leufs*3 Frameshift | 5.5 | KMT2D NM_003482 39 | 12 49426729 | c.11756_11758del p.Gln3919del Deletion | 5.7 |

| TP53 NM_000546 8 | 17 7577035 | c.902del p.Pro301Glnfs*44 Frameshift | 0.3 | TP53 NM_000546 7 | 17 7577539 | c.742C>T p.Arg248Trp Missense | 0.3 |

| Reference | Cases (n) | PD1 Staining Pattern | Molecular Methods | B/T-Cell Clonality | Key Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egan et al. 2020 [17] | 14 | Follicular Pattern (58%); Diffuse Pattern (8%); Reactive Pattern or Reduced Staining (33%) | sPCR-based clonality | IGH monoclonal TCR polyclonal | NA |

| Hurwitz et al. 2021 [21] | 3 | Follicular central (n = 1); Mixed follicular (central) and diffuse (n = 1); Mixed follicular (peripheral) and diffuse (n = 1) | sPCR-based clonality; Targeted NGS | IGH monoclonal TCR polyclonal | FC: NOTCH2 (FS), CREBBP (DEL), KLF2 (MS) MFD: NOTCH2 (NS), KLF2 (MS) MFPD: EZH2 (MS), TNFAIP3 (FS), TP53 (MS) |

| Deng et al. 2023 [18] | 3 | Reactive-like pattern (n = 1); Follicular pattern peripheral and central mixed (n = 1); Diffuse pattern tLBCL (n = 1) | sPCR-based clonality; Targeted NGS | IGH monoclonal TCR polyclonal | NOTCH2 (1/3; FS), KMT2D (3/3; DEL, FS, MS), TBL1XR1 (1/3; MS, SG), TNFAIP3 (2/3; FS), TNFRSF14 (1/3; DEL), EP300 (1/3; MS), KMT2C (1/3, MS), CD58 (1/3; MS) |

| Zamò et al. 2023 [19] | 8 | Nodular aggregates (75%) Diffuse pattern (25%) | Targeted NGS; clonality methods NA | IGH monoclonal TCR polyclonal | NOTCH2 (3/8), KLF2 (2/8), CREBBP (1/8), CD70 (1/8), IRF4 (1/8), SPEN (1/8), TMSB4X(1/8), BTG2(1/8), CCND3 (1/8), IRF8 (1/8), NOTCH1(1/8), TNFAIP3(1/8) |

| Present case | 1 | Predominantly central nodular | NGS-based clonality; Targeted NGS | IGH monoclonal TCR polyclonal | NOTCH2 (NS), TNFRSF14 (SS), KMT2D (FS, DEL), TP53 (FS, MS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Crisci, S.; De Chiara, A.; Oro, M.; Rivieccio, M.; Altobelli, A.; Mele, S.; Sirica, L.; Donnarumma, D.; Bonanni, M.; Cuccaro, A.; et al. Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma with Prominent Expansion of PD-1+ T-Follicular Helper Cells: A Persistent Diagnostic Challenge with a Heterogeneous Mutational Architecture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010051

Crisci S, De Chiara A, Oro M, Rivieccio M, Altobelli A, Mele S, Sirica L, Donnarumma D, Bonanni M, Cuccaro A, et al. Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma with Prominent Expansion of PD-1+ T-Follicular Helper Cells: A Persistent Diagnostic Challenge with a Heterogeneous Mutational Architecture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrisci, Stefania, Annarosaria De Chiara, Maria Oro, Maria Rivieccio, Annalisa Altobelli, Sara Mele, Letizia Sirica, Daniela Donnarumma, Matteo Bonanni, Annarosa Cuccaro, and et al. 2026. "Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma with Prominent Expansion of PD-1+ T-Follicular Helper Cells: A Persistent Diagnostic Challenge with a Heterogeneous Mutational Architecture" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010051

APA StyleCrisci, S., De Chiara, A., Oro, M., Rivieccio, M., Altobelli, A., Mele, S., Sirica, L., Donnarumma, D., Bonanni, M., Cuccaro, A., Fresa, A., De Filippi, R., & Pinto, A. (2026). Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma with Prominent Expansion of PD-1+ T-Follicular Helper Cells: A Persistent Diagnostic Challenge with a Heterogeneous Mutational Architecture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010051