Applications of Exosomes in Female Medicine: A Systematic Review of Molecular Biology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

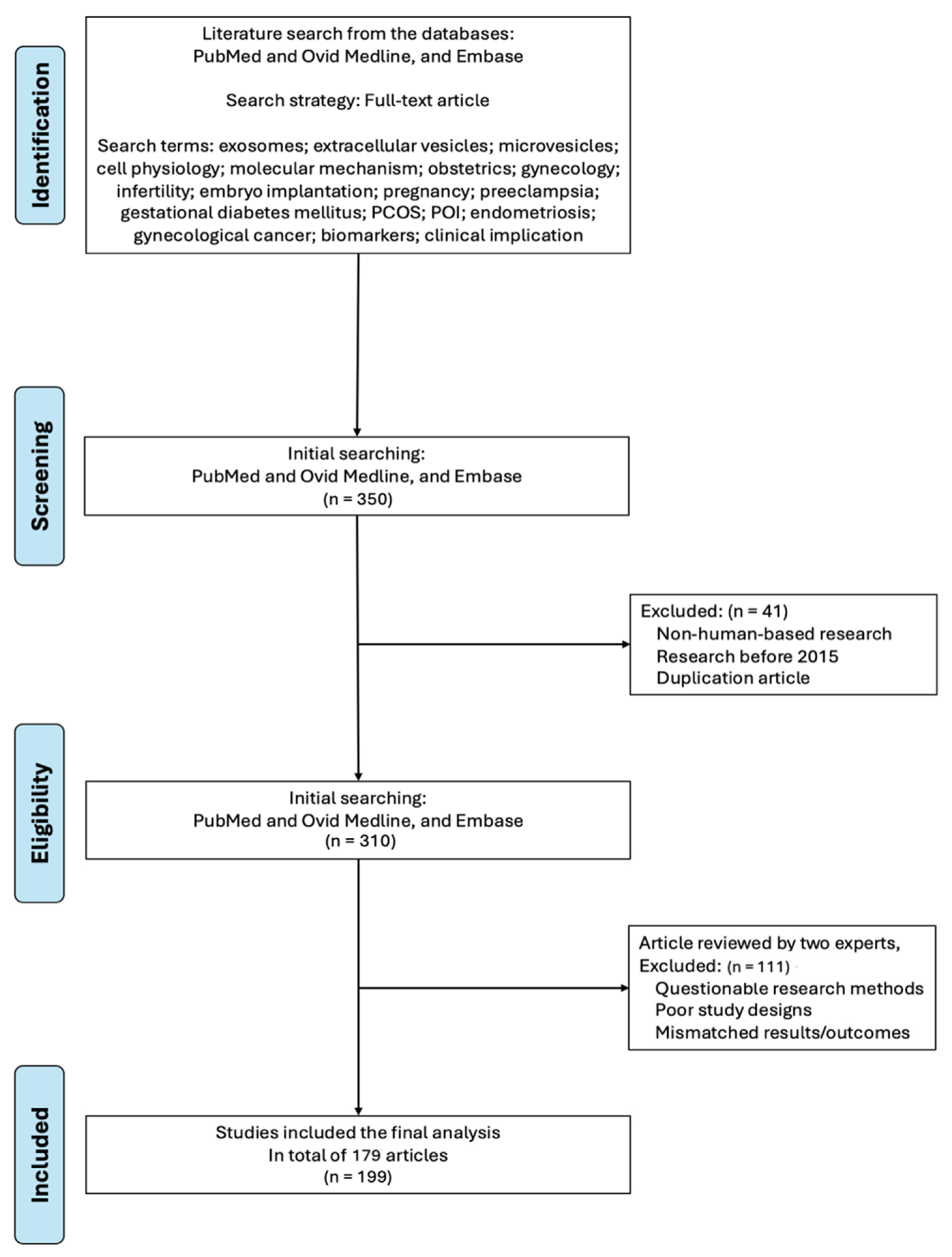

2. Method

3. Results and Discussion

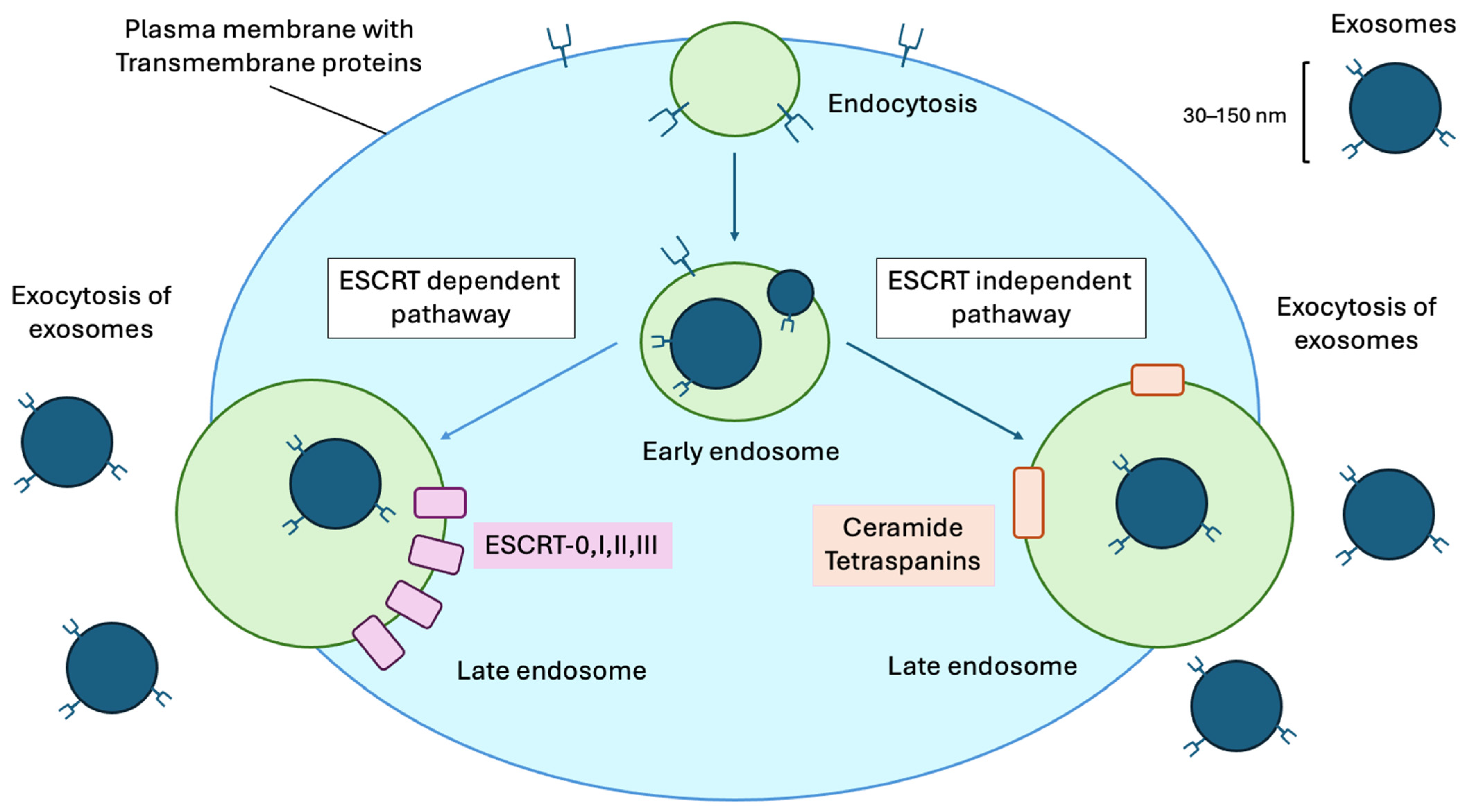

3.1. Exosome Characteristic and Biogenesis

3.1.1. ESCRT-Dependent Pathway

3.1.2. ESCRT-Independent Pathway

3.1.3. Accessory and Post-Translational Regulation

3.2. Cell Physiology and Intercellular Communication

3.2.1. Physiological Functions

3.2.2. Roles in Obstetrics

3.2.3. Roles in Gynecology and Reproductive Endocrinology

3.2.4. Intercellular Communication

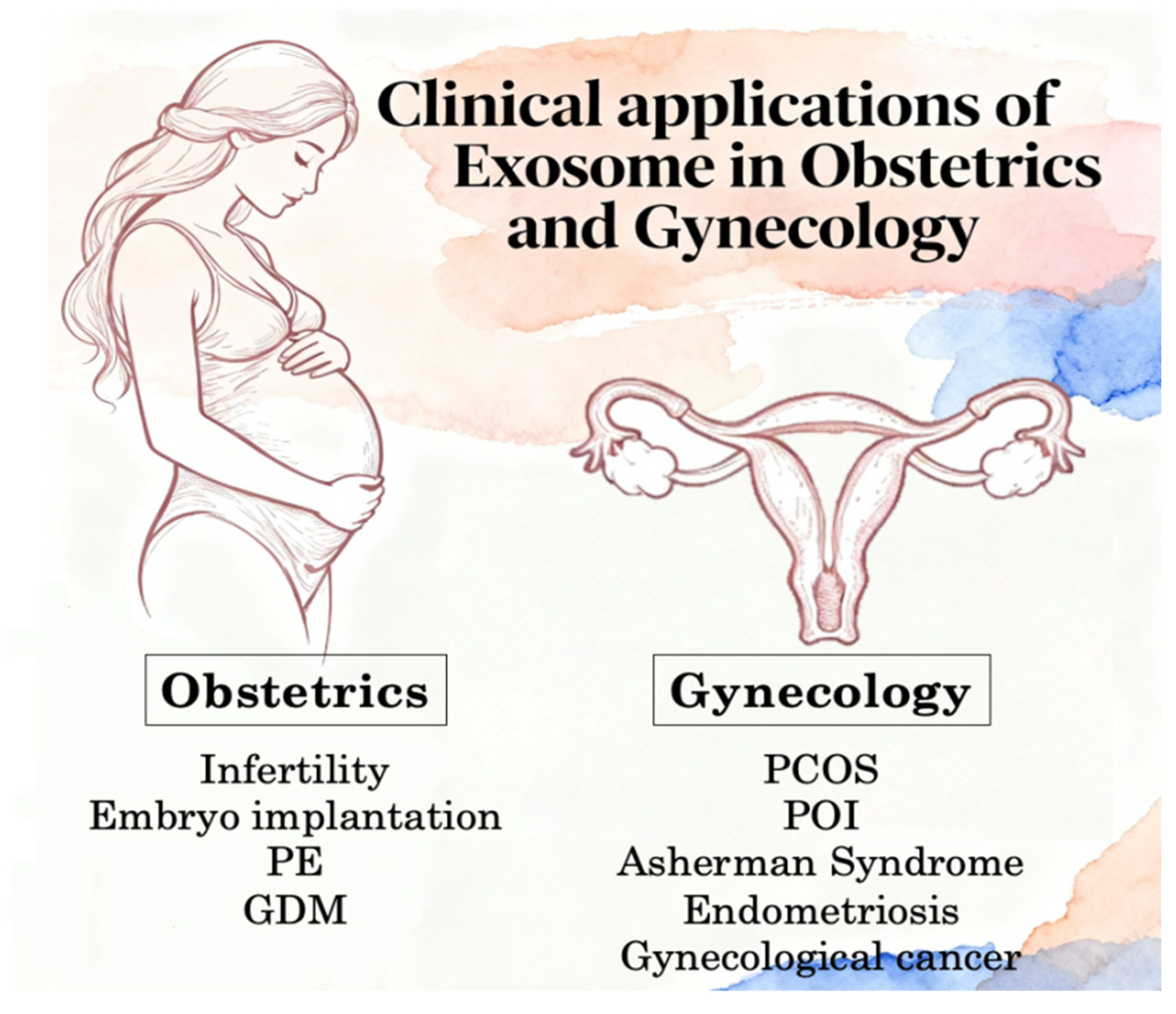

3.3. Clinical Applications in Obstetrics and Gynecology

3.3.1. Exosomes: Cellular Origin in Pregnancy, Standardization of Techniques, Diagnosis and Quantification

Cellular Origin in Normal Pregnancy

Standardization of Techniques

Diagnostic Value of Assays

- Omics-Based Profiling (Highest Value): High-throughput sequencing of exosomal cargo (miRNA, proteomic, lipidomic) offers the highest diagnostic specificity. Multi-marker panels from placenta-enriched EV fractions have demonstrated superior sensitivity for predicting PE and GDM compared to single-marker assays [121,124,125].

- Cell-Specific Immunophenotyping: Assays targeting STB-specific surface markers (e.g., PLAP+ flow cytometry or ELISA) provide moderate-to-high diagnostic value by specifically quantifying the “fetal signal” amid maternal noise and correlate strongly with placental stress [122].

- Bulk Concentration and Size (Lowest Specificity): While total EV concentration often increases in pathology, it lacks specificity due to high inter-individual variability and the influence of non-pregnancy factors (e.g., BMI, inflammation), limiting its standalone diagnostic utility [125].

Significance of Exosome Quantification

3.3.2. Exosomes in Obstetrics Disease

Infertility

Embryo Implantation

Preeclampsia (PE)

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

3.3.3. Exosomes in Gynecological Disease

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

Premature Ovarian Failure/Insufficiency (POF/POI)

Endometriosis

Asherman Syndrome

3.3.4. Gynecological Malignancies

Ovarian Cancer

Uterine and Endometrial Cancer

Cervical Cancer

3.4. Exosomal Biomarkers in OB/GYN Diagnostics and Therapeutic Applications

3.4.1. Diagnostic Advantages

3.4.2. Therapeutic Applications

3.5. Discussion: Challenges and Future Directions

3.5.1. Future Directions

3.5.2. Standardization and Biomarker Validation

3.5.3. Mechanistic Understanding and Multi-Omics Integration

3.5.4. Therapeutic Optimization and Manufacturing

3.5.5. Regulatory Framework and Technology Integration

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoi, A.; Villar-Prados, A.; Oliphint, P.A.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; De Hoff, P.; Morey, R.; Liu, J.; Roszik, J.; Clise-Dwyer, K.; et al. Mechanisms of nuclear content loading to exosomes. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stope, M.B.; Klinkmann, G.; Diesing, K.; Koensgen, D.; Burchardt, M.; Mustea, A. Heat Shock Protein HSP27 Secretion by Ovarian Cancer Cells Is Linked to Intracellular Expression Levels, Occurs Independently of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Pathway and HSP27’s Phosphorylation Status, and Is Mediated by Exosome Liberation. Dis. Markers 2017, 2017, 1575374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergauwen, G.; Tulkens, J.; Pinheiro, C.; Avila Cobos, F.; Dedeyne, S.; De Scheerder, M.A.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Impens, F.; Miinalainen, I.; Braems, G.; et al. Robust sequential biophysical fractionation of blood plasma to study variations in the biomolecular landscape of systemically circulating extracellular vesicles across clinical conditions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, G.; Nijman, H.W.; Stoorvogel, W.; Liejendekker, R.; Harding, C.V.; Melief, C.J.; Geuze, H.J. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liang, R.; Zheng, M.; Cai, L.; Fan, X. Surface-Functionalized Nanoparticles as Efficient Tools in Targeted Therapy of Pregnancy Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovic, R.A.; Collett, G.P.; Hole, P.; Ferguson, D.J.; Redman, C.W.; Sargent, I.L.; Tannetta, D.S. Isolation of syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles and exosomes and their characterisation by multicolour flow cytometry and fluorescence Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. Methods 2015, 87, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Wrzecińska, M.; Czerniawska-Piątkowska, E.; Kupczyński, R. Exosomes—Spectacular role in reproduction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muinelo-Romay, L.; Casas-Arozamena, C.; Abal, M. Liquid Biopsy in Endometrial Cancer: New Opportunities for Personalized Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.Y.; Dong, Y.P.; Sun, X.; Sui, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Mason, C.; Zhu, Q.; Han, S.X. High levels of serum glypican-1 indicate poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5525–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.W.; Ullah, K.; Khan, N.; Pan, H.T. Comprehensive profiling of serum microRNAs in normal and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtaz, C.J.; Reifschläger, L.; Strähle, L.; Feldheim, J.; Feldheim, J.J.; Schmitt, C.; Kiesel, M.; Herbert, S.L.; Wöckel, A.; Meybohm, P.; et al. Analysis of microRNAs in Exosomes of Breast Cancer Patients in Search of Molecular Prognostic Factors in Brain Metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.F.; Xu, X.; Bhandari, K.; Gin, A.; Rao, C.V.; Morris, K.T.; Hannafon, B.N.; Ding, W.Q. Isolation of extra-cellular vesicles in the context of pancreatic adenocarcinomas: Addition of one stringent filtration step improves recovery of specific microRNAs. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.; Kulick, N.; Rementer, R.J.B.; Fallon, J.K.; Sykes, C.; Schauer, A.P.; Malinen, M.M.; Mosedale, M.; Watkins, P.B.; Kashuba, A.D.M.; et al. Pregnancy-Related Hormones Increase Nifedipine Metabolism in Human Hepatocytes by Inducing CYP3A4 Expression. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, S.; Hannafon, B.N. Breast Cancer Microenvironment Cross Talk through Extracellular Vesicle RNAs. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lv, X.; Ru, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, N.; Xi, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Chang, R.; Xie, T.; et al. Circulating Exosomal Gastric Cancer-Associated Long Noncoding RNA1 as a Biomarker for Early Detection and Monitoring Progression of Gastric Cancer: A Multiphase Study. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrat, C.E.; Varlas, V.N.; Duică, F.; Antoniadis, P.; Danila, C.A.; Cretoiu, D.; Suciu, N.; Crețoiu, S.M.; Voinea, S.C. Pregnancy-Related Extracellular Vesicles Revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Li, X.; Zhong, J.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Lee, C.L.; Chiu, P.C.N. Placenta-Derived Exosomes as a Modulator in Maternal Immune Tolerance During Pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 671093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Yuan, M.; Li, D.; Sun, C.; Wang, G. Serum Exosomal MicroRNAs as Potential Circulating Biomarkers for Endometriosis. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 2456340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yokoi, A.; Kato, T.; Ochiya, T.; Yamamoto, Y. The clinical impact of intra- and extracellular miRNAs in ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, O.D.; Thistlethwaite, W.; Rozowsky, J.; Subramanian, S.L.; Lucero, R.; Shah, N.; Jackson, A.R.; Srinivasan, S.; Chung, A.; Laurent, C.D.; et al. exRNA Atlas Analysis Reveals Distinct Extracellular RNA Cargo Types and Their Carriers Present across Human Biofluids. Cell 2019, 177, 463–477.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.J.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Monckeberg, M.; Realini, O.; Hernández, M.; Rice, G.; Romero, R.; Saavedra, J.F.; Illanes, S.E.; Chaparro, A. Oral extracellular vesicles in early pregnancy can identify patients at risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, H.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Lolicato, F.; Heidarpour, M.; Pashazadeh, F.; Nouri, M.; Mahdipour, M. Evaluation of the association between exosomal levels and female reproductive system and fertility outcome during aging: A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Menon, R. Placental exosomes: A proxy to understand pregnancy complications. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 79, e12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandyari, S.; Elkafas, H.; Chugh, R.M.; Park, H.S.; Navarro, A.; Al-Hendy, A. Exosomes as Biomarkers for Female Reproductive Diseases Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capra, E.; Lange-Consiglio, A. The Biological Function of Extracellular Vesicles during Fertilization, Early Embryo-Maternal Crosstalk and Their Involvement in Reproduction: Review and Overview. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almiñana, C.; Bauersachs, S. Extracellular vesicles: Multi-signal messengers in the gametes/embryo-oviduct cross-talk. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin-Kujundzic, V.; Sola, I.M.; Predavec, N.; Potkonjak, A.; Somen, E.; Mioc, P.; Serman, A.; Vranic, S.; Serman, L. Novel Epigenetic Biomarkers in Pregnancy-Related Disorders and Cancers. Cells 2019, 8, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.; Nuzhat, Z.; Dixon, C.L.; Menon, R. Placental Exosomes During Gestation: Liquid Biopsies Carrying Signals for the Regulation of Human Parturition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X. The emerging roles and therapeutic potential of exosomes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashchenko, E.P.; Vysokikh, M.Y.; Marey, M.V.; Sidorova, K.O.; Manukhova, L.A.; Shkavro, N.N.; Uvarova, E.V.; Chuprynin, V.D.; Fatkhudinov, T.K.; Adamyan, L.V.; et al. Altered Glycolysis, Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Autophagy and Apoptosis in Peritoneal Endometriosis in Adolescents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, L.; Ma, S.; Lin, R.; Li, J.; Yang, S. Biogenesis and function of exosome lncRNAs and their role in female pathological pregnancy. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1191721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Van Oostdam, A.S.; Toro-Ortíz, J.C.; López, J.A.; Noyola, D.E.; García-López, D.A.; Durán-Figueroa, N.V.; Martínez-Martínez, E.; Portales-Pérez, D.P.; Salgado-Bustamante, M.; López-Hernández, Y. Placental exosomes isolated from urine of patients with gestational diabetes exhibit a differential profile expression of microRNAs across gestation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Choodinatha, H.K.; Kim, K.S.; Shin, K.; Kim, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Hong, J.W.; Lee, L.P. Understanding the role of soluble proteins and exosomes in non-invasive urine-based diagnosis of preeclampsia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Benítez, M.; Carbajo-García, M.C.; Corachán, A.; Faus, A.; Pellicer, A.; Ferrero, H. Proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles secreted by primary human epithelial endometrial cells reveals key proteins related to embryo implantation. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalo Cordeiro, M.; Roque, R.; Laranjeiro, B.; Carvalhos, C.; Figueiredo-Dias, M. Menstrual Blood Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes as Promising Therapeutic Tools in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency Induced by Gonadotoxic Systemic Anticancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.B.; Fields, D.A.; Pezant, N.P.; Kharoud, H.K.; Gulati, S.; Jacobs, K.; Gale, C.A.; Kharbanda, E.O.; Nagel, E.M.; Demerath, E.W.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Is Associated with Altered Abundance of Exosomal MicroRNAs in Human Milk. Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 172–185.e1, Erratum in Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbinian, N.; Hampe, M.; Martirosyan, D.; Bajwa, A.; Darbinyan, A.; Merabova, N.; Tatevosian, G.; Goetzl, L.; Amini, S.; Selzer, M.E. Fetal Brain-Derived Exosomal miRNAs from Maternal Blood: Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, L.A.; Sheller-Miller, S.; Russell, W.; Saade, G.R.; Dixon, C.L.; Urrabaz-Garza, R.; Menon, R. Fetal membrane extracellular vesicle profiling reveals distinct pathways induced by infection and inflammation in vitro. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 84, e13282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, E.; Vago, R.; Sanchez, A.M.; Podini, P.; Zarovni, N.; Murdica, V.; Rizzo, R.; Bortolotti, D.; Candiani, M.; Viganò, P. Secretome of in vitro cultured human embryos contains extracellular vesicles that are uptaken by the maternal side. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Long, L.; Xiao, H.; He, X. Cancer-Derived Exosomal miR-651 as a Diagnostic Marker Restrains Cisplatin Resistance and Directly Targets ATG3 for Cervical Cancer. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 1544784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiozzo, C.; Bustoros, M.; Lin, X.; Manzano De Mejia, C.; Gurzenda, E.; Chavez, M.; Hanna, I.; Aguiari, P.; Perin, L.; Hanna, N. Placental extracellular vesicles-associated microRNA-519c mediates endotoxin adaptation in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 681.e1–681.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, C.; Ohe, J.V.; Hass, R. Anti-Tumor Effects of Exosomes Derived from Drug-Incubated Permanently Growing Human MSC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheller, S.; Papaconstantinou, J.; Urrabaz-Garza, R.; Richardson, L.; Saade, G.; Salomon, C.; Menon, R. Amnion-Epithelial-Cell-Derived Exosomes Demonstrate Physiologic State of Cell under Oxidative Stress. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campoy, I.; Lanau, L.; Altadill, T.; Sequeiros, T.; Cabrera, S.; Cubo-Abert, M.; Pérez-Benavente, A.; Garcia, A.; Borrós, S.; Santamaria, A.; et al. Exosome-like vesicles in uterine aspirates: A comparison of ultracentrifugation-based isolation protocols. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmäe, S.; Koel, M.; Võsa, U.; Adler, P.; Suhorutšenko, M.; Laisk-Podar, T.; Kukushkina, V.; Saare, M.; Velthut-Meikas, A.; Krjutškov, K.; et al. Meta-signature of human endometrial receptivity: A meta-analysis and validation study of transcriptomic biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, K.; Qing, Y.; Li, D.; Cui, M.; Jin, P.; Xu, T. Proteomic and lipidomic analysis of exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells and ovarian surface epithelial cells. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zan, J.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhao, H.; Peng, Q.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Human Follicular Fluid-Derived Exosomes Reveals That Insufficient Folliculogenesis in Aging Women is Associated With Infertility. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2025, 24, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azumi, M.; Inubushi, S.; Yano, Y.; Obata, K.; Yamanaka, K.; Terai, Y. MiR-575 in Exosomes of Vaginal Discharge Is Downregulated in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2025, 22, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Than, N.G.; Romero, R.; Fitzgerald, W.; Gudicha, D.W.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Posta, M.; Zhou, F.; Bhatti, G.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Awonuga, A.O.; et al. Proteomic Profiles of Maternal Plasma Extracellular Vesicles for Prediction of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 92, e13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, D.; Liang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Wang, M.; Tang, X.; Zhuang, H.; Wang, H.; Yin, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Proteomic analysis of plasma total exosomes and placenta-derived exosomes in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus in the first and second trimesters. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ma, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Q.; Guo, X.; Chen, L.; Cao, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, X. Serum Exosomes From Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients Contain LRP1, Which Promotes the Migration of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cell. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2023, 22, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Leung, L.L.; Mak, C.S.L.; Wang, X.; Chan, W.S.; Hui, L.M.N.; Tang, H.W.M.; Siu, M.K.Y.; Sharma, R.; Xu, D.; et al. Tumor-secreted exosomal miR-141 activates tumor-stroma interactions and controls premetastatic niche formation in ovarian cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, D.M.; Fitzgerald, W.; Romero, R.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Gudicha, D.W.; Than, N.G.; Bosco, M.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Jung, E.; Meyyazhagan, A.; et al. Proteomic profile of extracellular vesicles in maternal plasma of women with fetal death. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2177529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.A.; Thomé, C.H.; Izumi, C.; Grassi, M.L.; Lanfredi, G.P.; Smolka, M.; Faça, V.M.; Candido Dos Reis, F.J. Proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and potential biomarkers of mesenchymal high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.; Dixon, C.L.; Cayne, S.; Radnaa, E.; Salomon, C.; Sheller-Miller, S. Differences in cord blood extracellular vesicle cargo in preterm and term births. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 87, e13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Pang, D.; Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Cui, J. Integrative single-cell and exosomal multi-omics uncovers SCNN1A and EFNA1 as non-invasive biomarkers and drivers of ovarian cancer metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1630794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, C.; Jing, X.; Xu, X. Exosomes derived from hypoxic mesenchymal stem cells restore ovarian function by enhancing angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, M.; Shang, J.; Zhou, J.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X. Hypoxic mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal circDennd2a regulates granulosa cell glycolysis by interacting with LDHA. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebara, N.; Scheel, J.; Skovronova, R.; Grange, C.; Marozio, L.; Gupta, S.; Giorgione, V.; Caicci, F.; Benedetto, C.; Khalil, A.; et al. Single extracellular vesicle analysis in human amniotic fluid shows evidence of phenotype alterations in preeclampsia. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X. Exosomes derived from hypoxic epithelial ovarian cancer cells deliver microRNAs to macrophages and elicit a tumor-promoted phenotype. Cancer Lett. 2018, 435, 80–91, Erratum in Cancer Lett. 2023, 586, 216292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Qi, J.; Zhao, F.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Li, P.; Tan, J. PDGFBB improved the biological function of menstrual blood-derived stromal cells and the anti-fibrotic properties of exosomes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, U.; Smith, B.Q.; Dorayappan, K.D.P.; Yoo, J.Y.; Maxwell, G.L.; Kaur, B.; Konishi, I.; O’Malley, D.; Cohn, D.E.; Selvendiran, K. Targeting TMEM205 mediated drug resistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma using oncolytic virus. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 130, Erratum in J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusar, V.; Kan, N.; Leonova, A.; Chagovets, V.; Tyutyunnik, V.; Khachatryan, Z.; Yarotskaya, E.; Sukhikh, G. Non-Invasive Assessment of Neurogenesis Dysfunction in Fetuses with Early-Onset Growth Restriction Using Fetal Neuronal Exosomes Isolating from Maternal Blood: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S.; Qi, X.; Gao, S.; Qi, J.; Li, P.; Tan, J. Exosomes derived from menstrual blood stromal cells ameliorated premature ovarian insufficiency and granulosa cell apoptosis by regulating SMAD3/AKT/MDM2/P53 pathway via delivery of thrombospondin-1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göhner, C.; Plösch, T.; Faas, M.M. Immune-modulatory effects of syncytiotrophoblast extracellular vesicles in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Placenta 2017, 60, S41–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Peng, P.; Kuang, Y.; Yang, J.; Cao, D.; You, Y.; Shen, K. Characterization of exosomes derived from ovarian cancer cells and normal ovarian epithelial cells by nanoparticle tracking analysis. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 4213–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, A.; Sawada, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Yagi, T.; Kinose, Y.; Kodama, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Kimura, T. Exosomal CD47 Plays an Essential Role in Immune Evasion in Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.; Maharaj, N. The immune-modulatory dynamics of exosomes in preeclampsia. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 311, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Yang, Z.; Cui, J.; Tao, H.; Ma, R.; Zhao, Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: A promising alternative in the therapy of preeclampsia. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Liu, H.; He, J.; Wu, J.; Yuan, C.; Wang, R.; Yuan, M.; Yang, D.; Deng, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Model construction and drug therapy of primary ovarian insufficiency by ultrasound-guided injection. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Richardson, L.S. Preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes: A disease of the fetal membranes. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H.; Alečković, M.; Lavotshkin, S.; Matei, I.; Costa-Silva, B.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Williams, C.; García-Santos, G.; Ghajar, C.; et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 883–891, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Z.; Shen, Y.; Feng, G.; Dai, F.; Yang, D.; Deng, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, R.; Yang, L.; et al. Targeting Decidual CD16(+) Immune Cells with Exosome-Based Glucocorticoid Nanoparticles for Miscarriage. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2406370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, R.; Rashidi, S.; Soleymani, B.; Bakhtiari, M.; Mohammadi, P.; Yarani, R.; Mansouri, K. The supportive role of stem cells-deived exosomes in the embryo implantation process by regulating oxidative stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 188, 118171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.X.; Lv, Y. MiR-99 Family of Exosomes Targets Myotubularin-related Protein 3 to Regulate Autophagy in Trophoblast Cells and Influence Insulin Resistance. J. Physiol. Investig. 2025, 68, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman-Gibson, S.; Chandiramani, C.; Stone, M.L.; Waker, C.A.; Rackett, T.M.; Maxwell, R.A.; Dhanraj, D.N.; Brown, T.L. Streamlined Analysis of Maternal Plasma Indicates Small Extracellular Vesicles are Significantly Elevated in Early-Onset Preeclampsia. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 2771–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysler, S.M.; Mulla, M.J.; Guerra, M.; Brosens, J.J.; Salmon, J.E.; Chamley, L.W.; Abrahams, V.M. Antiphospholipid antibody-induced miR-146a-3p drives trophoblast interleukin-8 secretion through activation of Toll-like receptor 8. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 22, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Hou, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, A.; Liu, S. Exploring the role of exosomal MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers in preeclampsia. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1385950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavina, G.; Mamillapalli, R.; Krikun, G.; Zhou, Y.; Gawde, N.; Taylor, H.S. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes shuttle microRNAs to endometrial stromal fibroblasts that promote tissue proliferation/regeneration/and inhibit differentiation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Fang, Z.; Dong, J.; Chen, S.; Mao, J.; Zhang, W.; Hai, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X. Maternal circulating exosomal miR-185-5p levels as a predictive biomarker in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L. miR-548az-5p induces amniotic epithelial cell senescence by regulating KATNAL1 expression in labor. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atukorala, I.; Hannan, N.; Hui, L. Immersed in a reservoir of potential: Amniotic fluid-derived extracellular vesicles. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Chen, H.; Zou, G.; Yuan, L.; Liu, P.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Jing, F.; Nie, X.; Liu, T.; et al. Human Amniotic Fluid Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Inhibit Apoptosis in Ovarian Granulosa Cell via miR-369-3p/YAF2/PDCD5/p53 Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3695848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, L.; Fóthi, Á.; Orosz, G.; Nagy, S.; Than, N.G.; Orbán, T.I. Exosomal small RNA profiling in first-trimester maternal blood explores early molecular pathways of preterm preeclampsia. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1321191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ou, Q.; Gao, L. The increased cfRNA of TNFSF4 in peripheral blood at late gestation and preterm labor: Its implication as a noninvasive biomarker for premature delivery. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1154025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Shahin, H. Extracellular vesicles in spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, M.; Solhjoo, S.; Palmerini, M.G.; Nematollahi-Mahani, S.N.; Ezzatabadipour, M. Granulosa cell insight: Unraveling the potential of menstrual blood-derived stem cells and their exosomes on mitochondrial mechanisms in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, X.; Chang, X.; Yao, J.; He, Q.; Shen, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, K. S100-A9 protein in exosomes derived from follicular fluid promotes inflammation via activation of NF-κB pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, M.; Li, W.X.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shang, J.; Shi, X.; Lu, J.; Xing, J.; et al. HuMSCs-derived exosomal YBX1 participates in oxidative damage repair in granulosa cells by stabilizing COX5B mRNA in an m5C-dependent manner. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voros, C.; Athanasiou, D.; Mavrogianni, D.; Varthaliti, A.; Bananis, K.; Athanasiou, A.; Athanasiou, A.; Papadimas, G.; Gkirgkinoudis, A.; Papapanagiotou, I.; et al. Exosomal Communication Between Cumulus-Oocyte Complexes and Granulosa Cells: A New Molecular Axis for Oocyte Competence in Human-Assisted Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.C.; Wang, L.F.; Zhang, Y.W.; Zhuo, Y.Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wei, X.Y.; Liu, Q.W.; Deng, K.Y.; Xin, H.B. Human urine stem cells protect against cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian failure by inhibiting SLC1A4-mediated outflux of intracellular serine in ovarian granulosa cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Pan, B.; Dong, X.; Guo, W. Correlation between steroid levels in follicular fluid and hormone synthesis related substances in its exosomes and embryo quality in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, C. Exosome-mediated communication in the ovarian follicle. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, B.; Xu, M.; Wu, M.; Lin, J.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Q.; Huang, G.; Hu, H. Improving Granulosa Cell Function in Premature Ovarian Failure with Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Exosome-Derived hsa_circ_0002021. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2024, 21, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tao, M.; Wei, M.; Du, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomal miR-323-3p promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of cumulus cells in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 3804–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endometriosis. World Health Organization. WHO Fact Sheets. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Zheng, L.; Sun, D.F.; Tong, Y. Exosomal miR-202 derived from leukorrhea as a potential biomarker for endometriosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605221147183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, L.; Lin, R.; Ma, S.; Li, J.; Yang, S. A comprehensive overview of exosome lncRNAs: Emerging biomarkers and potential therapeutics in endometriosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1199569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, H.M.; Greaves, E.; Quenby, S.; Dragovic, R.; Tapmeier, T.T.; Becker, C.M. The role of small extracellular vesicle-miRNAs in endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 2296–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Xu, W.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Na, Q. Enhancing exosome stability and delivery with natural polymers to prevent intrauterine adhesions and promote endometrial regeneration: A review. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Mei, S.; Cheng, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Che, X. Exosomal miR-92a-3p serves as a promising marker and potential therapeutic target for adenomyosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Yu, Q.; Long, Y. Unveiling the Pathological Landscape of Intrauterine Adhesion: Mechanistic Insights and Exosome-Biomaterial Therapeutic Innovations. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 9667–9694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, D.; Singh, A.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, M.K.; Roy, K.K.; Chauhan, S.C.; Kashyap, V.K. Emerging Roles and Potential Applications of Non-Coding RNAs in Cervical Cancer. Genes 2022, 13, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Gu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Yue, W.; Li, M. VIPAS39 confers ferroptosis resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer through exporting ACSL4. eBioMedicine 2025, 114, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuma, T.; Asare-Werehene, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Tsang, B.K. Exosomal Plasma Gelsolin Is an Immunosuppressive Mediator in the Ovarian Tumor Microenvironment and a Determinant of Chemoresistance. Cells 2022, 11, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, K.; Nanashima, N.; Yokoyama, Y.; Yoshioka, H.; Watanabe, J. Exosomal MicroRNA as Biomarkers for Diagnosing or Monitoring the Progression of Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma: A Pilot Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.H.; Du, Y.P.; Guan, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y. CircWHSC1 promotes ovarian cancer progression by regulating MUC1 and hTERT through sponging miR-145 and miR-1182. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, R.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. Circular RNAs and their emerging roles as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 473, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S.; Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; Baruteau, J. The exosome journey: From biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratta, S.; Tancini, B.; Sagini, K.; Delo, F.; Chiaradia, E.; Urbanelli, L.; Emiliani, C. Lysosomal Exocytosis, Exosome Release and Secretory Autophagy: The Autophagic- and Endo-Lysosomal Systems Go Extracellular. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, I.; Nabet, B.Y. Exosomes in the tumor microenvironment as mediators of cancer therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, A.; Soudi, S.; Malekpour, K.; Mahmoudi, M.; Rahimi, A.; Hashemi, S.M.; Varma, R.S. Immune cells-derived exosomes function as a double-edged sword: Role in disease progression and their therapeutic applications. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, J.; Hill, A.F. Exosomes in the Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 26589–26597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Fan, B.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X. Extracellular vesicles in normal pregnancy and pregnancy-related diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 4377–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J.; Cheng, S.B.; Padbury, J.; Sharma, S. Placental extracellular vesicles and pre-eclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyemi, T.; Cerdeira, A.S.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Rahbar, M.; Logenthiran, P.; Redman, C.; Vatish, M. Preeclampsia and syncytiotrophoblast membrane extracellular vesicles (STB-EVs). Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 1793–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannetta, D.S.; Hunt, K.; Jones, C.I.; Davidson, N.; Coxon, C.H.; Ferguson, D.; Redman, C.W.; Gibbins, J.M.; Sargent, I.L.; Tucker, K.L. Syncytiotrophoblast Extracellular Vesicles from Pre-Eclampsia Placentas Differentially Affect Platelet Function. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, S.; Ge, Z.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Placenta-derived exosomes exacerbate beta cell dysfunction in gestational diabetes mellitus through delivery of miR-320b. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1282075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, M.V.C.; Pantazi, P.; Holder, B. Circulating extracellular vesicles in healthy and pathological pregnancies: A scoping review of methodology, rigour and results. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, 12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pónusz-Kovács, D.; Csákvári, T.; Sántics-Kajos, L.F.; Elmer, D.; Pónusz, R.; Kovács, B.; Várnagy, Ákos; Kovács, K.; Bódis, J.; Boncz, I. Epidemiological disease burden and annual, nationwide health insurance treatment cost of female infertility based on real-world health insurance claims data in Hungary. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ning, Y.; Ye, H. Global, regional, and national burden of female infertility and trends from 1990 to 2021 with projections to 2050 based on the GBD 2021 analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtinger, R.; Rodosthenous, R.S.; Adir, M.; Mansour, A.; Racowsky, C.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Hauser, R. Extracellular microRNAs in follicular fluid and their potential association with oocyte fertilization and embryo quality: An exploratory study. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lv, J.; Tang, R.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fei, X.; Chian, R.; Xie, Q. Association of exosomal microRNAs in human ovarian follicular fluid with oocyte quality. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 534, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, Y.; Özgül, M.; Gökap, S.; Ok, G.; Tan, A.; Vatansever, H.S. The correlation between unexplained infertility and exosomes. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E.A.; Stephens, K.K.; Winuthayanon, W. Extracellular Vesicles and the Oviduct Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfandyari, S.; Chugh, R.M.; Park, H.S.; Hobeika, E.; Ulin, M.; Al-Hendy, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Bio Organ for Treatment of Female Infertility. Cells 2020, 9, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.X.; Li, X.L. The Complicated Effects of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Cargos on Embryo Implantation. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 681266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Fu, Y.; Shen, L.; Quan, S. MicroRNA signatures in plasma and plasma exosome during window of implantation for implantation failure following in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Deng, G.; Ruan, X.; Chen, S.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, G.; Gao, J. Exosomal MicroRNAs in Serum as Potential Biomarkers for Ectopic Pregnancy. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3521859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luddi, A.; Zarovni, N.; Maltinti, E.; Governini, L.; Leo, V.; Cappelli, V.; Quintero, L.; Paccagnini, E.; Loria, F.; Piomboni, P. Clues to Non-Invasive Implantation Window Monitoring: Isolation and Characterisation of Endometrial Exosomes. Cells 2019, 8, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Mouillet, J.F.; Sorkin, A.; Sadovsky, Y. Trophoblastic extracellular vesicles and viruses: Friends or foes? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 85, e13345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Groom, K.; Chamley, L.; Chen, Q. Melatonin, a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Preeclampsia, Reduces the Extrusion of Toxic Extracellular Vesicles from Preeclamptic Placentae. Cells 2021, 10, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wu, M.; Huang, H.; Zou, L.; Luo, Q. Pathogenic mechanisms of preeclampsia with severe features implied by the plasma exosomal mirna profile. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9140–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannetta, D.; Masliukaite, I.; Vatish, M.; Redman, C.; Sargent, I. Update of syncytiotrophoblast derived extracellular vesicles in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 119, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Kumar, S.; Hyett, J.; Salomon, C. Molecular Targets of Aspirin and Prevention of Preeclampsia and Their Potential Association with Circulating Extracellular Vesicles during Pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Tao, H. Small RNA sequencing of exosomal microRNAs reveals differential expression of microRNAs in preeclampsia. Medicine 2023, 102, e35597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.R.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.P. Prediction of severe preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction based on serum placental exosome miR-520a-5p levels during the first-trimester. Medicine 2024, 103, e38188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devor, E.; Santillan, D.; Scroggins, S.; Warrier, A.; Santillan, M. Trimester-specific plasma exosome microRNA expression profiles in preeclampsia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3116–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, P.; Vatish, M.; Duarte, R.; Moodley, J.; Mackraj, I. Exosomal microRNA profiling in early and late onset preeclamptic pregnant women reflects pathophysiology. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5637–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, L.; Habertheuer, A.; Ram, C.; Korutla, L.; Schwartz, N.; Hu, R.W.; Reddy, S.; Freas, A.; Zielinski, P.D.; Harmon, J.; et al. Syncytiotrophoblast extracellular microvesicle profiles in maternal circulation for noninvasive diagnosis of preeclampsia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.K. Cell- and size-specific analysis of placental extracellular vesicles in maternal plasma and pre-eclampsia. Transl. Res. 2018, 201, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, G.; Guanzon, D.; Kinhal, V.; Elfeky, O.; Lai, A.; Longo, S.; Nuzhat, Z.; Palma, C.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Menon, R.; et al. Oxygen tension regulates the miRNA profile and bioactivity of exosomes released from extravillous trophoblast cells—Liquid biopsies for monitoring complications of pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, E.U.; Mamerto, T.P.; Chung, G.; Villavieja, A.; Gaus, N.L.; Morgan, E.; Pineda-Cortel, M.R.B. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Harbinger of the Vicious Cycle of Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modzelewski, R.S.-R.M.; Matuszewski, W.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E.M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus—Recent Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, T.; Gulati, R.; Uppal, A.; Kumari, S.R.; Tripathy, S.; Ranjan, P.; Janardhanan, R. Prospecting of exosomal-miRNA signatures as prognostic marker for gestational diabetes mellitus and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1097337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.N.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Yang, M.M.; Chen, C.; Zhao, B.H.; Huang, H.F.; Luo, Q. MiRNAs in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Potential Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 4632745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liang, B.; Chen, X. Exosomal circular RNA circ_0074673 regulates the proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells via the microRNA-1200/MEOX2 axis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 6782–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Wen, J. Circular RNA expression profiles in umbilical cord blood exosomes from normal and gestational diabetes mellitus patients. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frørup, C.; Mirza, A.H.; Yarani, R.; Nielsen, L.B.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Damm, P.; Svare, J.; Engelbrekt, C.; Størling, J.; Johannesen, J.; et al. Plasma Exosome-Enriched Extracellular Vesicles From Lactating Mothers With Type 1 Diabetes Contain Aberrant Levels of miRNAs During the Postpartum Period. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 744509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Huang, Q.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhuang, X.X.; Lin, S.; Shi, Q.Y. Therapeutic potential of exosomes/miRNAs in polycystic ovary syndrome induced by the alteration of circadian rhythms. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 918805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, R.; Asare-Werehene, M.; Wyse, B.A.; Abedini, A.; Pan, B.; Gutsol, A.; Jahangiri, S.; Szaraz, P.; Burns, K.D.; Vanderhyden, B.; et al. Granulosa cell-derived miR-379-5p regulates macrophage polarization in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1104550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, R.; Wyse, B.A.; Asare-Werehene, M.; Esfandiarinezhad, F.; Abedini, A.; Pan, B.; Urata, Y.; Gutsol, A.; Vinas, J.L.; Jahangiri, S.; et al. Androgen-induced exosomal miR-379-5p release determines granulosa cell fate: Cellular mechanism involved in polycystic ovaries. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidi, M.; Karimabadi, K.; Ghanbari, E.; Rezakhani, L.; Khazaei, M. Stem cells and exosomes: As biological agents in the diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1269266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Huo, P.; Cui, K.; Wei, H.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Lei, X.; Zhang, S. Follicular fluid-derived exosomal miR-143-3p/miR-155-5p regulate follicular dysplasia by modulating glycolysis in granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 61, Erratum in Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, C.; Wyse, B.A.; Tsang, B.K.; Librach, C.L. Extracellular vesicles and their content in the context of polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometriosis: A review. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Improve Ovarian Function and Proliferation of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency by Regulating the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 711902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Lu, J.; Ding, C.; Zou, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, H. Exosomes derived from human adipose mesenchymal stem cells improve ovary function of premature ovarian insufficiency by targeting SMAD. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yu, Z.; Yao, D.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jia, R. Mesenchymal stem cells therapy: A promising method for the treatment of uterine scars and premature ovarian failure. Tissue Cell 2022, 74, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.L.; Jeong, D.U.; Noh, E.J.; Jeon, H.J.; Lee, D.C.; Kang, M.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.K.; Han, A.R.; Kang, J.; et al. Exosomal miR-205-5p Improves Endometrial Receptivity by Upregulating E-Cadherin Expression through ZEB1 Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankiewicz, K.; Laudański, P.; Issat, T. The Role of Noncoding RNA in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Liu, M.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, L. Exosomal lncRNA CHL1-AS1 Derived from Peritoneal Macrophages Promotes the Progression of Endometriosis via the miR-610/MDM2 Axis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 5451–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Fang, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, W.; Wang, L.; Xia, X. Construction and topological analysis of an endometriosis-related exosomal circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network. Aging 2021, 13, 12607–12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhan, F.; Zhong, Y.; Tan, B. Effects of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived from exosomes on migration ability of endometrial glandular epithelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gao, Y. Screening differentially expressed genes between endometriosis and ovarian cancer to find new biomarkers for endometriosis. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, M. Exosomes released from M2 macrophages transfer miR-221-3p contributed to EOC progression through targeting CDKN1B. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 5976–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.J.; Lin, X.J.; Tang, X.Y.; Zheng, T.T.; Lin, Y.Y.; Hua, K.Q. Exosomal Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 Promotes Angiogenesis and Predicts Poor Prognosis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1960–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, T.; Deng, Y.; Liu, D. Research progress on anti-ovarian cancer mechanism of miRNA regulating tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1050917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Ma, J.; Adu-Amankwaah, J.; Xie, G.; Wang, Y.; Tai, W.; Sun, Z.; Huang, C.; Chen, G.; Fu, T.; et al. Exosomal integrin alpha 3 promotes epithelial ovarian cancer cell migration via the S100A7/p-ERK signaling pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2025, 57, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Ding, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhou, H.; Huang, B.; Huang, T.; Li, M.; et al. Exosomal CMTM4 Induces Immunosuppressive Macrophages to Promote Ovarian Cancer Progression and Attenuate Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e04436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Lu, C. Circular RNA Foxo3 enhances progression of ovarian carcinoma cells. Aging 2021, 13, 22432–22443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yoo, J.; Ho, J.Y.; Jung, Y.; Lee, S.; Hur, S.Y.; Choi, Y.J. Plasma-derived exosomal miR-4732-5p is a promising noninvasive diagnostic biomarker for epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Sasaki, H.; Ueda, S.; Miyamoto, S.; Terada, S.; Konishi, H.; Kogata, Y.; Ashihara, K.; Fujiwara, S.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Serum exosomal microRNA-34a as a potential biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Gui, R. Circulating exosomal circFoxp1 confers cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, A.; Sawada, K.; Nakamura, K.; Kinose, Y.; Nakatsuka, E.; Kobayashi, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Ishida, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kodama, M.; et al. Exosomal miR-99a-5p is elevated in sera of ovarian cancer patients and promotes cancer cell invasion by increasing fibronectin and vitronectin expression in neighboring peritoneal mesothelial cells. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgendorf, S.K.; Thaker, P.H.; Arevalo, J.M.; Goodheart, M.J.; Slavich, G.M.; Sood, A.K.; Cole, S.W. Biobehavioral modulation of the exosome transcriptome in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2018, 124, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Sawada, K.; Kinose, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Toda, A.; Nakatsuka, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Mabuchi, S.; Morishige, K.I.; Kurachi, H.; et al. Exosomes Promote Ovarian Cancer Cell Invasion through Transfer of CD44 to Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.J.; Liu, B.; Linghu, H. Identifying genes as potential prognostic indicators in patients with serous ovarian cancer resistant to carboplatin using integrated bioinformatics analysis. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Sawada, K.; Nakamura, K.; Yoshimura, A.; Miyamoto, M.; Shimizu, A.; Ishida, K.; Nakatsuka, E.; Kodama, M.; Hashimoto, K.; et al. Exosomal miR-1290 is a potential biomarker of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and can discriminate patients from those with malignancies of other histological types. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, W.; Feng, Y.; Sang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Xi, X. Downregulation of miR-145-5p in cancer cells and their derived exosomes may contribute to the development of ovarian cancer by targeting CT. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Dean, D.C.; Hornicek, F.J.; Shi, H.; Duan, Z. Exosomes promote pre-metastatic niche formation in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorayappan, K.D.P.; Gardner, M.L.; Hisey, C.L.; Zingarelli, R.A.; Smith, B.Q.; Lightfoot, M.D.S.; Gogna, R.; Flannery, M.M.; Hays, J.; Hansford, D.J.; et al. A Microfluidic Chip Enables Isolation of Exosomes and Establishment of Their Protein Profiles and Associated Signaling Pathways in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 3503–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, A.; Sawada, K.; Kimura, T. Pathophysiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Exploitation of Exosomes in Ovarian Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.T.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Luo, Y.L.; Luo, Q.; Chen, S.B.; Zhao, J.C.; Chen, Q.R. Exosomal lncRNA NEAT1 from cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitates endometrial cancer progression via miR-26a/b-5p-mediated STAT3/YKL-40 signaling pathway. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziechciowski, M.; Zapala, B.; Skotniczny, K.; Gawlik, K.; Pawlica-Gosiewska, D.; Piwowar, M.; Balajewicz-Nowak, M.; Basta, P.; Solnica, B.; Pitynski, K. Diagnostic and prognostic relevance of microparticles in peripheral and uterine blood of patients with endometrial cancer. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.J.; Zhang, J.; Xie, F.; Wu, J.N.; Ye, J.F.; Wang, J.; Wu, K.; Li, M. CD45RO(-)CD8(+) T cell-derived exosomes restrict estrogen-driven endometrial cancer development via the ERβ/miR-765/PLP2/Notch axis. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5330–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skog, J.; Würdinger, T.; van Rijn, S.; Meijer, D.H.; Gainche, L.; Sena-Esteves, M.; Curry, W.T., Jr.; Carter, B.S.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Breakefield, X.O. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.F.; Ma, J.; Huang, L.; Yi, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wu, X.G.; Yan, R.M.; Liang, L.; Zhong, M.; Yu, Y.H.; et al. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma-secreted exosomal miR-221-3p promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis by targeting VASH1. Oncogene 2019, 38, 1256–1268, Erratum in Oncogene 2022, 41, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Z.; Zhang, S.Q.; Deng, X.L.; Qiang, J.H. Serum Exosomal lncRNA DLX6-AS1 Is a Promising Biomarker for Prognosis Prediction of Cervical Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 1533033821990060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, M.; Qian, L.; Lin, X.; Song, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y. The STAT3-miR-223-TGFBR3/HMGCS1 axis modulates the progression of cervical carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2313–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wei, M.; Kang, Y.; Xing, J.; Zhao, Y. Circular RNA circ_PVT1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote metastasis of cervical cancer. Aging 2020, 12, 20139–20151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, H.; Hayashi, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kuranaga, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Terai, Y.; Akao, Y.; et al. The therapeutic potential of exosomal miR-22 for cervical cancer radiotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2020, 21, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Huang, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, M.; Xu, T. Long non-coding RNA in cervical cancer: From biology to therapeutic opportunity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Sample Source | Key Biomarkers/Cargo | Cargo Type | Clinical Utility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infertility | Follicular fluid Serum | ENO1, HSP90B1, Fetuin-B, Complement C7, CD9, APOC4 | Proteins |

| [47,112] |

| Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (RPL) | Plasma | miR-185-5p | miRNA |

| [79] |

| Preeclampsia (PE) | Maternal plasma, serum or urine | miR-675-5p, miR-3614-5p, miR-520a-5p | miRNA, Proteins |

| [59,121,124,125,126] |

| Gestational Diabetes (GDM) | Maternal plasma or urineUmbilical cord blood | miR-99 family, circRNAs, Placental proteins | miRNA, circRNA, Proteins |

| [32,135,136] |

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) | Follicular fluid Serum | miR-379-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-155-5p, miR-323-3p, S100-A9 | miRNA, Proteins |

| [87,94,139,140,141,142] |

| Premature Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) | Serum Ovarian tissue | miR-205-5p (MSC-derived) | miRNA |

| [147] |

| Endometriosis | Peritoneal fluid Serum | lncRNA CHL1-AS1, miR-134-5p, miR-197-5p, miR-22-3p, miR-610 | lncRNA, miRNA |

| [18,149,150,151] |

| Asherman Syndrome | Uterine tissue | MSC-derived anti-inflammatory factors | miRNA, Proteins |

| [99,146] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Serum Ascites | circFoxp1, miR-221-3p, miR-1290, miR-99a-5p, CD44, CD47 | circRNA, miRNA, Proteins |

| [19,60,67,107,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Uterine tissue Serum | lncRNA NEAT1, Tissue Factor (TF), CD144+ microparticles | lncRNA, Microparticles |

| [171,172,173] |

| Cervical Cancer | Cervix tissue Body fluid | miR-1286, lncRNA DLX6-AS1, miR-22 | miRNA, lncRNA |

| [174,175,176,177,178,179] |

| Condition | Sample Source | Key Cargo/Pathway | Experimental Model | Reported Therapeutic Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POI | Human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes | Hippo pathway, SMAD3–AKT signaling | Chemotherapy- or toxin-induced POI animal models, granulosa cell culture |

| [35,64,144,145] |

| Hypoxia-preconditioned MSC-derived exosomes | miR-205-5p to PTEN–PI3K–AKT–mTOR | Animal POI models |

| [57,147,148] | |

| Human amniotic fluid MSC-derived exosomes | miR-369-3p/YAF2/PDCD5/p53 axis | Granulosa cell apoptosis models |

| [82] | |

| PCOS | MSC-derived exosomes (e.g., bone marrow/umbilical cord) | miR-323-3p and other regulatory miRNAs | PCOS animal models and in vitro granulosa cells |

| [94,139,140,141,142] |

| Asherman syndrome | MSC-derived exosomes (e.g., menstrual blood, UC-MSC) | Anti-fibrotic factors; SMAD3/AKT/MDM2/p53 modulation | Rodent intrauterine adhesion models |

| [99,146] |

| Endometriosis | Human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes | Pro-regenerative factors affecting epithelial migration | In vitro endometrial glandular epithelial cell models |

| [35,64,149,152] |

| Ovarian cancer | Drug-incubated human MSC-derived exosomes | Antitumor drug cargo (e.g., triptolide or cytotoxics) | Ovarian cancer cell lines and xenograft models |

| [42,170] |

| Tumor-derived or MSC exosomes | miR-221-3p, integrins, YBX1, gelsolin, etc. | In vitro and in vivo EOC/SOC models |

| [88,103,153,174] |

| Clinical Implication | Exosome Source/Feature | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Screening | Serum, urine, follicular fluid | Early detection of PE, GDM, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer |

| Diagnosis | Specific exosomal miRNAs/proteins | Diagnosing PCOS, POI, endometriosis, cancer type/type staging |

| Prognosis/Monitoring | Circulating exosomal signatures | Predicting PE/GDM onset, cancer progression, recurrence |

| Therapeutic (Experimental) | Engineered exosomes (MSC, hUCMSC, loaded drugs) | Ovarian rejuvenation (POI), PCOS recovery, targeted drug delivery for cancers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mariadas, H.; Chen, J.-H.; Chen, K.-H. Applications of Exosomes in Female Medicine: A Systematic Review of Molecular Biology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010504

Mariadas H, Chen J-H, Chen K-H. Applications of Exosomes in Female Medicine: A Systematic Review of Molecular Biology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010504

Chicago/Turabian StyleMariadas, Heidi, Jie-Hong Chen, and Kuo-Hu Chen. 2026. "Applications of Exosomes in Female Medicine: A Systematic Review of Molecular Biology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010504

APA StyleMariadas, H., Chen, J.-H., & Chen, K.-H. (2026). Applications of Exosomes in Female Medicine: A Systematic Review of Molecular Biology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010504