GJB2-Related Hearing Loss: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, Natural History, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

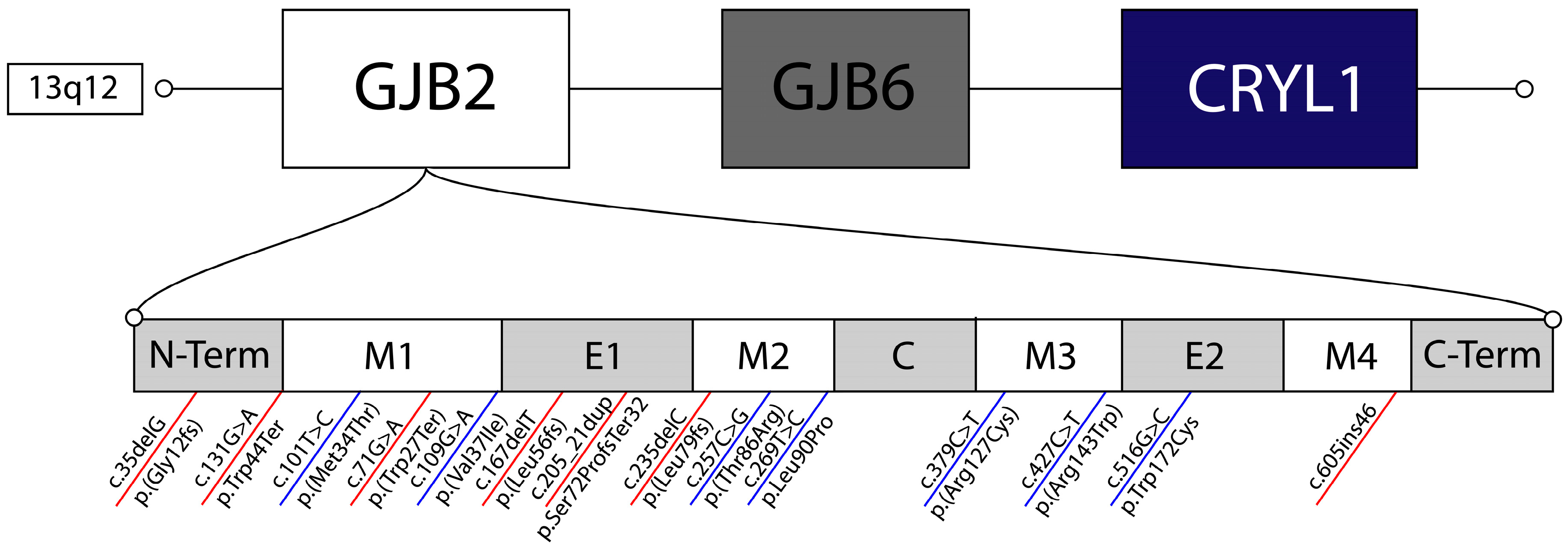

3. Molecular Basis of GJB2 Hearing Loss

3.1. Truncating Mutations

3.2. Non-Truncating Mutations

| Mutation Type | Protein Change | Chromosomal Change | Molecular Consequence | Phenotype | Origin | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truncating | p.Gly12fs | c.35delG | Frameshift | Severe to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Europe | [23,24,65] |

| p.Leu79fs | c.235delC | Frameshift | Severe to profound bilateral congenital NSHL, with some cases of asymmetric NSHL | China | [26,27,66] | |

| p.Trp24Ter | c.71G>A | Termination | Variable, Mild to moderate bilateral congenital NSHL | South Asia | [54] | |

| p.Leu56fs | c.167delT | Frameshift | Severe to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Eurasia | [44,67] | |

| p.Trp44Ter | c.131G>A | Termination | Severe to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Guatemala | [36] | |

| p.Ser72ProfsTer32 | c.205_21dupTTCCCCA | Termination | Severe bilateral congenital NSHL | West Africa | [35] | |

| - | c.605ins46 | Termination | Severe to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Japan | [37] | |

| Non-Truncating | p.Arg143Trp | c.427C>T | Missense | Moderate to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Ghana | [46,47] |

| p.Met34Thr | c.101T>C | Missense | Mild to moderate bilateral congenital NSHL | Europe | [54] | |

| p.Val37Ile | c.109G>A | Missense | Mild to moderate bilateral congenital NSHL | East Asia | [55] | |

| p.Thr86Arg | c.257C>G | Missense | Moderate to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | East Asia | [37,68] | |

| p.Arg127Cys | c.379C>T | Missense | Moderate to severe bilateral congenital NSHL | Undetermined | [45] | |

| p.Trp172Cys | c.516G>C | Missense | Mild to profound bilateral congenital NSHL | Eastern Europe | [69] | |

| p.Leu90Pro | c.269T>C | Missense | Mild to moderate bilateral congenital NSHL | Middle East | [7,70] |

4. The DFNB1 Locus Beyond the Coding Sequence

5. Clinical Manifestations and Natural History

5.1. Audiology

5.2. Cochlear Implant Outcomes

6. Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

7. Therapeutics and Future Directions

7.1. Gene Therapy

7.2. Allele-Specific Suppression

7.3. Gene Editing

7.4. Model Systems and Translational Barriers

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Powell, D.S.; Oh, E.S.; Reed, N.S.; Lin, F.R.; Deal, J.A. Hearing Loss and Cognition: What We Know and Where We Need to Go. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 769405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, A.J. The cellular basis of hearing: The biophysics of hair cells. Science 1985, 230, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiber, S.; Gwilliam, K.; Hertzano, R.; Avraham, K.B. The Genomics of Auditory Function and Disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2022, 23, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.J.; Chowdhry, A.A.; Kurima, K.; Hood, L.J.; Keats, B.; Berlin, C.I.; Morell, R.J.; Friedman, T.B. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic neurosensory deafness at DFNB1 not associated with the compound-heterozygous GJB2 (connexin 26) genotype M34T/167delT. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, C.; Rudy, N.; Smith, R.J.; Robin, N.H. Genetic testing hearing loss: The challenge of non syndromic mimics. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 150, 110872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, A.E.; Hildebrand, M.S.; Odell, A.M.; Smith, R.J. Genetic Hearing Loss Overview. In GeneReviews(®) [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993–2025; first published 14 February 1999; updated 3 April 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20301607/ (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Snoeckx, R.L.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Feldmann, D.; Marlin, S.; Denoyelle, F.; Waligora, J.; Mueller-Malesinska, M.; Pollak, A.; Ploski, R.; Murgia, A.; et al. GJB2 Mutations and Degree of Hearing Loss: A Multicenter Study. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsell, D.P.; Dunlop, J.; Stevens, H.P.; Lench, N.J.; Liang, J.N.; Parry, G.; Mueller, R.F.; Leigh, I.M. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature 1997, 387, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y. Mechanisms of congenital hearing loss caused by GJB2 gene mutations and current progress in gene therapy. Gene 2025, 946, 149326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Avraham, K.B. Hearing Loss: Mechanisms Revealed by Genetics and Cell Biology. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liao, R.; Yin, X.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, L.; Yan, M.; Zhou, J.; et al. The pathogenesis of common Gjb2 mutations associated with human hereditary deafness in mice. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Chang, Q.; Park, H.; Jeon, C.; Lin, X.; Bok, J.; Kim, U. Functional Evaluation of GJB2 Variants in Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Lin, P.; Lo, M.; Chen, H.; Lee, C.; Tsai, C.; Lin, Y.; Tsai, S.; Liu, T.; Hsu, C.; et al. Genetic Factors Contribute to the Phenotypic Variability in GJB2-Related Hearing Impairment. J. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 25, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, D.T.; Jin, N.; Tu, Z.; Lin, H.H. Upstream genomic sequence of the human connexin26. Gene 1997, 199, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shave, S.; Botti, C.; Kwong, K. Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 69, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaiez, H.; Chamberlin, G.P.; Fischer, S.M.; Welp, C.L.; Prasad, S.D.; Taggart, R.T.; Castillo, I.D.; Camp, G.V.; Smith, R.J.H. GJB2: The spectrum of deafness-causing allele variants and their phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2004, 24, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Wang, Y.; An, L.; Zeng, B.; Wang, Y.; Frishman, D.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Tang, W.; Xu, H. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Phenotypes of GJB2 Missense Variants. Biology 2023, 12, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posukh, O.L.; Maslova, E.A.; Danilchenko, V.Y.; Zytsar, M.V.; Orishchenko, K.E. Functional Consequences of Pathogenic Variants of the GJB2 Gene (Cx26) Localized in Different Cx26 Domains. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, D.; Tekin, M. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness genes: A review. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2012, 17, 2213–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, K.; Nishio, S.-Y.; Hattori, M.; Usami, S.-I. Ethnic-Specific Spectrum of GJB2 and SLC26A4 Mutations. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2015, 124, 61S–76S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.; Chang, K.W. GJB2-associated hearing loss: Systematic review of worldwide prevalence, genotype, and auditory phenotype. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, E34–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, H.; Kupsch, P.; Sudendey, J.; Winterhager, E.; Jahnke, K.; Lautermann, J. Mutations in the connexin26/GJB2 gene are the most common event in non-syndromic hearing loss among the German population. Hum. Mutat. 2001, 17, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, A.; Arnos, K.S.; Xia, X.J.; Welch, K.O.; Blanton, S.H.; Friedman, T.B.; Sanchez, G.G.; Liu, X.Z.; Morell, R.; Nance, W.E. Frequency and distribution of GJB2 (connexin 26) and GJB6 (connexin 30) mutations in a large North American repository of deaf probands. Genet. Med. 2003, 5, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, M.; Akar, N.; Cin, S.; Blanton, S.H.; Xia, X.J.; Liu, X.Z.; Nance, W.E.; Pandya, A. Connexin 26 (GJB2) mutations in the Turkish population: Implications for the origin and high frequency of the 35delG mutation in Caucasians. Hum. Genet. 2001, 108, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, N.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Bai, L.; Han, D.; Dai, P. Evolutionary origin of pathogenic GJB2 alleles in China. Clin. Genet. 2022, 102, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Park, H.; Ouyang, X.M.; Pandya, A.; Doi, K.; Erdenetungalag, R.; Du, L.L.; Matsushiro, N.; Nance, W.E.; Griffith, A.J.; et al. Evidence of a founder effect for the 235delC mutation of GJB2 (connexin 26) in east Asians. Hum. Genet. 2003, 114, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Xia, X.J.; Ke, X.M.; Ouyang, X.M.; Du, L.L.; Liu, Y.H.; Angeli, S.; Telischi, F.F.; Nance, W.E.; Balkany, T.; et al. The prevalence of connexin 26 (GJB2) mutations in the Chinese population. Hum. Genet. 2002, 111, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, T.; Ikeda, K.; Kure, S.; Matsubara, Y.; Oshima, T.; Watanabe, K.I.; Kawase, T.; Narisawa, K.; Takasaka, T. Novel mutations in the connexin 26 gene (GJB2) responsible for childhood deafness in the Japanese population. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 90, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, M.; Vijaya, R.; Ghosh, M.; Shastri, S.; Kabra, M.; Menon, P.S.N. Screening of families with autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment (ARNSHI) for mutations in GJB2 gene: Indian scenario. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 120A, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RamShankar, M.; Girirajan, S.; Dagan, O.; Ravi Shankar, H.M.; Jalvi, R.; Rangasayee, R.; Avraham, K.B.; Anand, A. Contribution of connexin26 (GJB2) mutations and founder effect to non-syndromic hearing loss in India. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, R.S.; Ganapathy, A.; Jalvi, R.; Srikumari Srisailapathy, C.R.; Malhotra, V.; Chadha, S.; Agarwal, A.; Ramesh, A.; Rangasayee, R.R.; Anand, A. Functional consequences of novel connexin 26 mutations associated with hereditary hearing loss. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Xiang, G.; Chai, X.; Qing, J.; Shang, H.; Zou, B.; Mittal, R.; Shen, J.; Smith, R.J.H.; Fan, Y.; et al. Screening of deafness-causing DNA variants that are common in patients of European ancestry using a microarray-based approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.M.; Ahmmed, H.S.; Al-Khafaji, S.M. Connexin 26 (GJB2) gene mutations linked with autosomal recessive non-syndromic sensor neural hearing loss in the Iraqi population. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toure, M.; Amalou, G.; Raise, I.A.; Mobio, N.M.A.; Malki, A.; Barakat, A. First report of an Ivorian family with nonsyndromic hearing loss caused by GJB2 compound heterozygous variants. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2025, 89, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza, C.; Menendez, I.; Herrera, M.; Castellanos, P.; Amado, C.; Maldonado, F.; Rosales, L.; Escobar, N.; Guerra, M.; Alvarez, D.; et al. A Mayan founder mutation is a common cause of deafness in Guatemala. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Lu, Y.; Xing, G.; Cao, X. A novel compound heterozygous mutation in the GJB2 gene causing non-syndromic hearing loss in a family. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 33, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Yu, F.; Han, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, D.; Kang, D.; et al. GJB2 mutation spectrum in 2063 Chinese patients with nonsyndromic hearing impairment. J. Transl. Med. 2009, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Bae, J.W.; Kim, S.; Chung, K.W.; Drayna, D.; Kim, U.K.; Lee, S.H. Molecular analysis of the GJB2, GJB6 and SLC26A4 genes in Korean deafness patients. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuge, I.; Ohtsuka, A.; Matsunaga, T.; Usami, S. Identification of 605ins46, a novel GJB2 mutation in a Japanese family. Auris Nasus Larynx 2002, 29, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryns, K.; Orzan, E.; Murgia, A.; Huygen, P.L.M.; Moreno, F.; Del Castillo, I.; Parker Chamberlin, G.; Azaiez, H.; Prasad, S.; Cucci, R.A.; et al. A genotype-phenotype correlation for GJB2 (connexin 26) deafness. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 41, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Juárez, A.A.; Lugo-Trampe, J.D.J.; Campos-Acevedo, L.D.; Lugo-Trampe, A.; Treviño-González, J.L.; De-La-Cruz-Ávila, I.; Martínez-De-Villarreal, L.E. GJB2 and GJB6 mutations are an infrequent cause of autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss in residents of Mexico. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, S.I. Phenotype/genotype correlations in a DFNB1 cohort with ethnical diversity. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 2014–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna, M.A.; Feldman, H.A.; Neault, M.W.; Frangulov, A.; Wu, B.; Fligor, B.; Rehm, H.L. Audiologic Phenotype and Progression in GJB2 (Connexin 26) Hearing Loss. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, A.; Kashio, A.; Koyama, M.; Urata, S.; Koyama, H.; Yamasoba, T. Hearing and Hearing Loss Progression in Patients with GJB2 Gene Mutations: A Long-Term Follow-Up. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadey, S.M.; Quaye, O.; Amedofu, G.K.; Awandare, G.A.; Wonkam, A. Screening for GJB2-R143W-Associated Hearing Impairment: Implications for Health Policy and Practice in Ghana. Public Health Genom. 2020, 23, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, E.T.; Adadey, S.M.; Esoh, K.; Jonas, M.; de Kock, C.; Amenga-Etego, L.; Awandare, G.A.; Wonkam, A. Age Estimate of GJB2-p.(Arg143Trp) Founder Variant in Hearing Impairment in Ghana, Suggests Multiple Independent Origins across Populations. Biology 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, A. Bioinformatic Analysis of GJB2 Gene Missense Mutations. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 71, 1623–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Lu, Y.; Chan, Y.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Chang, Y.; Lin, S.; Liu, T.; Hsu, C.; Chen, P.; Yang, L.; et al. Simulation-predicted and -explained inheritance model of pathogenicity confirmed by transgenic mice models. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 5698–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Suga, M.; Yamashita, E.; Oshima, A.; Fujiyoshi, Y.; Tsukihara, T. Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 Å resolution. Nature 2009, 458, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, P.M.; Harris, D.J.; Comer, B.C.; Askew, J.W.; Fowler, T.; Smith, S.D.; Kimberling, W.J. Novel Mutations in the Connexin 26 Gene (GJB2) That Cause Autosomal Recessive (DFNB1) Hearing Loss. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlin, S.; Garabédian, E.N.; Roger, G.; Moatti, L.; Matha, N.; Lewin, P.; Petit, C.; Denoyelle, F. Connexin 26 gene mutations in congenitally deaf children: Pitfalls for genetic counseling. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001, 127, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, D.; Denoyelle, F.; Loundon, N.; Weil, D.; Garabedian, E.; Couderc, R.; Joannard, A.; Schmerber, S.; Delobel, B.; Leman, J.; et al. Clinical evidence of the nonpathogenic nature of the M34T variant in the connexin 26 gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 12, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Oza, A.M.; del Castillo, I.; Duzkale, H.; Matsunaga, T.; Pandya, A.; Kang, H.P.; Mar-Heyming, R.; Guha, S.; Moyer, K.; et al. Consensus interpretation of the p.Met34Thr and p.Val37Ile variants in GJB2 by the ClinGen Hearing Loss Expert Panel. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, S.; Wang, Z. Analysis of GJB2 gene mutations spectrum and the characteristics of individuals with c.109G>A in Western Guangdong. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pshennikova, V.G.; Barashkov, N.A.; Romanov, G.P.; Teryutin, F.M.; Solov’ev, A.V.; Gotovtsev, N.N.; Nikanorova, A.A.; Nakhodkin, S.S.; Sazonov, N.N.; Morozov, I.V.; et al. Comparison of Predictive In Silico Tools on Missense Variants in GJB2, GJB6, and GJB3 Genes Associated with Autosomal Recessive Deafness 1A (DFNB1A). Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 5198931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzzone, R.; Veronesi, V.; Gomès, D.; Bicego, M.; Duval, N.; Marlin, S.; Petit, C.; D’Andrea, P.; White, T.W. Loss-of-function and residual channel activity of connexin26 mutations associated with non-syndromic deafness. FEBS Lett. 2003, 533, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, H.; Lee, K.Y.; Dinh, E.H.; Chang, Q.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, S.H.; Bok, J.; Lin, X.; Kim, U. Different functional consequences of two missense mutations in the GJB2 gene associated with non-syndromic hearing loss. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, E716–E727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posukh, O.L.; Zytsar, M.V.; Bady-Khoo, M.; Danilchenko, V.Y.; Maslova, E.A.; Barashkov, N.A.; Bondar, A.A.; Morozov, I.V.; Maximov, V.N.; Voevoda, M.I. Unique Mutational Spectrum of the GJB2 Gene and Its Pathogenic Contribution to Deafness in Tuvinians (Southern Siberia, Russia): A High Prevalence of Rare Variant c.516G>C (p.Trp172Cys). Genes 2019, 10, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Fang, P.; Ward, P.A.; Schmitt, E.; Darilek, S.; Manolidis, S.; Oghalai, J.S.; Roa, B.B.; Alford, R.L. DNA sequence analysis of GJB2, encoding connexin 26: Observations from a population of hearing impaired cases and variable carrier rates, complex genotypes, and ethnic stratification of alleles among controls. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 140A, 2401–2415, Erratum in Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2008, 146A, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, H.M.; Saunders, K.; Kelly, T.M.; Osborn, A.H.; Wilcox, S.; Cone-Wesson, B.; Wunderlich, J.L.; Du Sart, D.; Kamarinos, M.; Gardner, R.J.M.; et al. Prevalence and nature of connexin 26 mutations in children with non-syndromic deafness. Med. J. Aust. 2001, 175, 191–194, Erratum in Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, E.B.; Kaul, V.; Paschall, J.; Church, D.M.; Bunke, B.; Kunig, D.; Moreno-De-Luca, D.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; Mulle, J.G.; Warren, S.T.; et al. An evidence-based approach to establish the functional and clinical significance of copy number variants in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkenhäger, R.; Lüblinghoff, N.; Prera, E.; Schild, C.; Aschendorff, A.; Arndt, S. Autosomal dominant prelingual hearing loss with Palmoplantar Keratoderma syndrome: Variability in clinical expression from mutations of R75W and R75Q in the GJB2 gene. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2010, 152A, 1798–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Paris, J.; Waldhaus, J.; Gordhandas, J.A.; Pique, L.; Schrijver, I. Comparative functional characterization of novel non-syndromic GJB2 gene variant p.Gly45Arg and lethal syndromic variant p.Gly45Glu. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laer, L.; Coucke, P.; Mueller, R.F.; Caethoven, G.; Flothmann, K.; Prasad, S.D.; Chamberlin, G.P.; Houseman, M.; Taylor, G.R.; Van de Heyning, C.M.; et al. A common founder for the 35delG GJB2gene mutation in connexin 26 hearing impairment. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 38, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, N.; Kang, D.; Yang, S.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Dai, P. Hearing Phenotypes of Patients with Hearing Loss Homozygous for the GJB2 c.235delc Mutation. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8841522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhemileva, L.U.; Barashkov, N.A.; Posukh, O.L.; Khusainova, R.I.; Akhmetova, V.L.; Kutuev, I.A.; Gilyazova, I.R.; Tadinova, V.N.; Fedorova, S.A.; Khidiyatova, I.M.; et al. Carrier frequency of GJB2 gene mutations c.35delG, c.235delC and c.167delT among the populations of Eurasia. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Zhuang, W.; Yuan, N.; Sun, T.; Gao, J.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, K. A Novel GJB2 compound heterozygous mutation c.257C>G (p.T86R)/c.176del16 (p.G59A fs*18) causes sensorineural hearing loss in a Chinese family. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32, e22444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zytsar, M.V.; Bady-Khoo, M.S.; Danilchenko, V.Y.; Maslova, E.A.; Barashkov, N.A.; Morozov, I.V.; Bondar, A.A.; Posukh, O.L. High Rates of Three Common GJB2 Mutations c.516G>C, c.-23+1G>A, c.235delC in Deaf Patients from Southern Siberia Are Due to the Founder Effect. Genes 2020, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, F.J.; del Castillo, I. DFNB1 Non-syndromic Hearing Impairment: Diversity of Mutations and Associated Phenotypes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.J.; Azaiez, H.; Booth, K. GJB2-Related Autosomal Recessive Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss. In GeneReviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Bick, S., Mirzaa, G.M., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993–2025; first published 28 September 1998; updated 20 July 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1272/ (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Lin, Y.; Wu, P.; Tsai, C.; Lin, Y.; Lo, M.; Hsu, S.; Lin, P.; Erdenechuluun, J.; Wu, H.; Hsu, C.; et al. Hearing Impairment with Monoallelic GJB2 Variants. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayoun, A.N.A.; Mason-Suares, H.; Frisella, A.L.; Bowser, M.; Duffy, E.; Mahanta, L.; Funke, B.; Rehm, H.L.; Amr, S.S. Targeted Droplet-Digital PCR as a Tool for Novel Deletion Discovery at the DFNB1 Locus. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safka Brozkova, D.; Uhrova Meszarosova, A.; Lassuthova, P.; Varga, L.; Staněk, D.; Borecká, S.; Laštůvková, J.; Čejnová, V.; Rašková, D.; Lhota, F.; et al. The Cause of Hereditary Hearing Loss in GJB2 Heterozygotes—A Comprehensive Study of the GJB2/DFNB1 Region. Genes 2021, 12, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeha, N.; Koh, A.L.; Kam, S.; Lim, J.Y.; Goh, D.L.M.; Jamuar, S.S.; Graves, N. Reduced resource utilization with early use of next-generation sequencing in rare genetic diseases in an Asian cohort. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2022, 188, 3482–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petillo, R.; De Maggio, I.; Piscopo, C.; Chetta, M.; Tarsitano, M.; Chiriatti, L.; Sannino, E.; Torre, S.; D’Antonio, M.; D’Ambrosio, P.; et al. Genomic Testing in Adults with Undiagnosed Rare Conditions: Improvement of Diagnosis Using Clinical Exome Sequencing as a First-Tier Approach. Clin. Genet. 2025, 108, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Thiry, M. Recent insights into gap junction biogenesis in the cochlea. Dev. Dyn. 2023, 252, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerer, I.; Sagi, M.; Ben-Neriah, Z.; Wang, T.; Levi, H.; Abeliovich, D. A deletion mutation in GJB6 cooperating with a GJB2 mutation in trans in non-syndromic deafness: A novel founder mutation in Ashkenazi Jews. Hum. Mutat. 2001, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Castillo, I.; Villamar, M.; Moreno-Pelayo, M.A.; del Castillo, F.J.; Alvarez, A.; Tellería, D.; Menéndez, I.; Moreno, F. A deletion involving the connexin 30 gene in nonsyndromic hearing impairment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, I.; Moreno-Pelayo, M.A.; Del Castillo, F.J.; Brownstein, Z.; Marlin, S.; Adina, Q.; Cockburn, D.J.; Pandya, A.; Siemering, K.R.; Chamberlin, G.P.; et al. Prevalence and evolutionary origins of the del (GJB6-D13S1830) mutation in the DFNB1 locus in hearing-impaired subjects: A multicenter study. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 73, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares-Ruiz, N.; Blanchet, P.; Mondain, M.; Claustres, M.; Roux, A. A large deletion including most of GJB6 in recessive non syndromic deafness: A digenic effect? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 10, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, F.J.; Rodríguez-Ballesteros, M.; Alvarez, A.; Hutchin, T.; Leonardi, E.; de Oliveira, C.A.; Azaiez, H.; Brownstein, Z.; Avenarius, M.R.; Marlin, S.; et al. A novel deletion involving the connexin-30 gene, del (GJB6-d13s1854), found in trans with mutations in the GJB2 gene (connexin-26) in subjects with DFNB1 non-syndromic hearing impairment. J. Med. Genet. 2005, 42, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, D.; Le Maréchal, C.; Jonard, L.; Thierry, P.; Czajka, C.; Couderc, R.; Ferec, C.; Denoyelle, F.; Marlin, S.; Fellmann, F. A new large deletion in the DFNB1 locus causes nonsyndromic hearing loss. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 52, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliznetz, E.A.; Lalayants, M.R.; Markova, T.G.; Balanovsky, O.P.; Balanovska, E.V.; Skhalyakho, R.A.; Pocheshkhova, E.A.; Nikitina, N.V.; Voronin, S.V.; Kudryashova, E.K.; et al. Update of the GJB2/DFNB1 mutation spectrum in Russia: A founder Ingush mutation del (GJB2-D13S175) is the most frequent among other large deletions. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilch, E.; Azaiez, H.; Fisher, R.A.; Elfenbein, J.; Murgia, A.; Birkenhäger, R.; Bolz, H.; Da Silva-Costa, S.M.; Del Castillo, I.; Haaf, T.; et al. A novel DFNB1 deletion allele supports the existence of a distant cis-regulatory region that controls GJB2 and GJB6 expression. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, S.; Nishio, S.; Yokota, Y.; Moteki, H.; Kumakawa, K.; Usami, S. Diagnostic pitfalls for GJB2-related hearing loss: A novel deletion detected by Array-CGH analysis in a Japanese patient with congenital profound hearing loss. Clin. Case Rep. 2018, 6, 2111–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yu, L.; Li, D.; Gao, Q.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Bi, G.; Wu, H.; Zhao, S. Human CRYL1, a novel enzyme-crystallin overexpressed in liver and kidney and downregulated in 58% of liver cancer tissues from 60 Chinese patients, and four new homologs from other mammalians. Gene 2003, 302, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, G.A.; Diñeiro, M.; Huete, A.R.; Capín, R.; Santiago, A.; Vargas, A.A.R.; Carrero, D.; Martínez, E.L.; Aguiar, B.; Fischer, A.; et al. A Novel Recurrent 200 kb CRYL1 Deletion Underlies DFNB1A Hearing Loss in Patients from Northwestern Spain. Genes 2025, 16, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautermann, J.; ten Cate, W.F.; Altenhoff, P.; Grümmer, R.; Traub, O.; Frank, H.-.; Jahnke, K.; Winterhager, E. Expression of the gap-junction connexins 26 and 30 in the rat cochlea. Cell Tissue Res. 1998, 294, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forge, A.; Marziano, N.K.; Casalotti, S.O.; Becker, D.L.; Jagger, D. The inner ear contains heteromeric channels composed of cx26 and cx30 and deafness-related mutations in cx26 have a dominant negative effect on cx30. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2003, 10, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marziano, N.K.; Casalotti, S.O.; Portelli, A.E.; Becker, D.L.; Forge, A. Mutations in the gene for connexin 26 (GJB2) that cause hearing loss have a dominant negative effect on connexin 30. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, B.; Michel, V.; Pesch, J.; Lautermann, J.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Söhl, G.; Jahnke, K.; Winterhager, E.; Herberhold, C.; Hardelin, J.; et al. Connexin30 (Gjb6)-deficiency causes severe hearing impairment and lack of endocochlear potential. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Salmon, M.; Regnault, B.; Cayet, N.; Caille, D.; Demuth, K.; Hardelin, J.; Janel, N.; Meda, P.; Petit, C. Connexin30 deficiency causes instrastrial fluid-blood barrier disruption within the cochlear stria vascularis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6229–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nabec, A.; Collobert, M.; Le Maréchal, C.; Marianowski, R.; Férec, C.; Moisan, S. Whole-Genome Sequencing Improves the Diagnosis of DFNB1 Monoallelic Patients. Genes 2021, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.J. Cis-regulatory mutations in human disease. Brief. Funct. Genom. Proteom. 2009, 8, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, M.; Xia, X.; Erdenetungalag, R.; Cengiz, F.B.; White, T.W.; Radnaabazar, J.; Dangaasuren, B.; Tastan, H.; Nance, W.E.; Pandya, A. GJB2 Mutations in Mongolia: Complex Alleles, Low Frequency, and Reduced Fitness of the Deaf. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2010, 74, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashef, A.; Nikzat, N.; Bazzazadegan, N.; Fattahi, Z.; Sabbagh-Kermani, F.; Taghdiri, M.; Azadeh, B.; Mojahedi, F.; Khoshaeen, A.; Habibi, H.; et al. Finding mutation within non-coding region of GJB2 reveals its importance in genetic testing of Hearing Loss in Iranian population. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Propst, E.J.; Blaser, S.; Stockley, T.L.; Harrison, R.V.; Gordon, K.A.; Papsin, B.C. Temporal Bone Imaging in GJB2 Deafness. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 2178–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, S.B.; Mutai, H.; Nakano, A.; Arimoto, Y.; Taiji, H.; Morimoto, N.; Sakata, H.; Adachi, N.; Masuda, S.; Sakamoto, H.; et al. GJB2-associated hearing loss undetected by hearing screening of newborns. Gene 2013, 532, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Pandya, A.; Angeli, S.; Telischi, F.F.; Arnos, K.S.; Nance, W.E.; Balkany, T. Audiological features of GJB2 (connexin 26) deafness. Ear Hear. 2005, 26, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ko, H.; Tsou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, P.; Wu, C. Long-Term Cochlear Implant Outcomes in Children with GJB2 and SLC26A4 Mutations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, S.; Usami, S. Outcomes of cochlear implantation for the patients with specific genetic etiologies: A systematic literature review. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2017, 137, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, S.I.; Suarez, H.; Lopez, A.; Balkany, T.J.; Liu, X.Z. Influence of DFNB1 Status on Expressive Language in Deaf Children with Cochlear Implants. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Budenz, C.L.; Weisstuch, A.S.; Babb, J.; Roland, J.T.; Waltzman, S.B. Predictability of cochlear implant outcome in families. Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xiang, J.; Sun, X.; Song, N.; Liu, X.; Cai, Q.; Yang, J.; Ye, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Genome Sequencing Unveils the Role of Copy Number Variants in Hearing Loss and Identifies Novel Deletions with Founder Effect in the DFNB1 Locus. Hum. Mutat. 2024, 2024, 9517114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, K.; Nishio, S.; Usami, S.; Deafness Gene Study Consortium. A large cohort study of GJB2 mutations in Japanese hearing loss patients. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, N.; Smith, R.J.H.; Van Camp, G. Forty-six genes causing nonsyndromic hearing impairment: Which ones should be analyzed in DNA diagnostics? Mutat. Res. 2009, 681, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsebner, R.; Ludwig, M.; Lucas, T.; de Jong, D.; Hamader, G.; del Castillo, I.; Parzefall, T.; Baumgartner, W.; Schoefer, C.; Szuhai, K.; et al. Identification of a SNP in a regulatory region of GJB2 associated with idiopathic nonsyndromic autosomal recessive hearing loss in a multicenter study. Otol. Neurotol. 2013, 34, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akil, O.; Dyka, F.; Calvet, C.; Emptoz, A.; Lahlou, G.; Nouaille, S.; Boutet De Monvel, J.; Hardelin, J.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Avan, P.; et al. Dual AAV-mediated gene therapy restores hearing in a DFNB9 mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4496–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moyed, H.; Cepeda, A.P.; Jung, S.; Moser, T.; Kügler, S.; Reisinger, E. A dual-AAV approach restores fast exocytosis and partially rescues auditory function in deaf otoferlin knock-out mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, T.; Chen, H.; Kusch, K.; Behr, R.; Vona, B. Gene therapy for deafness: Are we there now? EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Q.; Tang, H.; Hu, S.; Gao, K.; et al. AAV1-hOTOF gene therapy for autosomal recessive deafness 9: A single-arm trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 2317–2325, Erratum in Lancet 2024, 403, 2292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01040-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landegger, L.D. Novel AAV-based GJB2 gene therapy restores hearing function. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2957–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, D.; He, Y.; Shu, Y. Advances in gene therapy hold promise for treating hereditary hearing loss. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Tan, F.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Wei, H.; Li, N.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Lu, L.; et al. Combined AAV-mediated specific Gjb2 expression restores hearing in DFNB1 mouse models. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 3006–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Xie, L.; Qiu, Y.; Kong, C.; Yin, G.; Kong, W.; Sun, Y. Viral-Mediated Connexin 26 Expression Combined with Dexamethasone Rescues Hearing in a Conditional Gjb2 Null Mice Model. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2406510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanchenko, M.V.; Booth, K.T.A.; Karavitaki, K.D.; Antonellis, L.M.; Nagy, M.A.; Peters, C.W.; Price, S.; Li, Y.; Lytvyn, A.; Ward, A.; et al. Cell-specific delivery of GJB2 restores auditory function in mouse models of DFNB1 deafness and mediates appropriate expression in NHP cochlea. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukaji, T.; Arai, D.; Tsutsumi, H.; Nakagawa, R.; Matsumoto, F.; Ikeda, K.; Nureki, O.; Kamiya, K. AAV-mediated base editing restores cochlear gap junction in GJB2 dominant-negative mutation-associated syndromic hearing loss model. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e185193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y. Recent advances in CRISPR-Cas system for the treatment of genetic hearing loss. Am. J. Stem Cells 2023, 12, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Doda, D.; Alonso Jimenez, S.; Rehrauer, H.; Carreño, J.F.; Valsamides, V.; Di Santo, S.; Widmer, H.R.; Edge, A.; Locher, H.; van der Valk, W.H.; et al. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived inner ear organoids recapitulate otic development in vitro. Development 2023, 150, dev201865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Morris, J.A.; Gonzalez, T.; Blanton, S.H.; Angeli, S.I.; Liu, X.Z. GJB2-Related Hearing Loss: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, Natural History, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010491

Morris JA, Gonzalez T, Blanton SH, Angeli SI, Liu XZ. GJB2-Related Hearing Loss: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, Natural History, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010491

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorris, Julia Anne, Tomas Gonzalez, Susan H. Blanton, Simon Ignacio Angeli, and Xue Zhong Liu. 2026. "GJB2-Related Hearing Loss: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, Natural History, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010491

APA StyleMorris, J. A., Gonzalez, T., Blanton, S. H., Angeli, S. I., & Liu, X. Z. (2026). GJB2-Related Hearing Loss: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations, Natural History, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010491