Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Molecular Profiling of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of H/L and NHW Cohorts

2.2. Genomic Comparisons Across Age Groups and Ancestral Backgrounds

2.2.1. Baseline Characteristics of the H/L and NHW Cohorts

2.2.2. Clinical Distribution of NHW Patients by Age at Onset, Treatment Status, and Tumor Characteristics

2.2.3. Ethnic Patterns Among EOCRC Cases by Treatment Status

2.3. JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations by Age, Ancestry, and Treatment Status

2.3.1. Within-Ancestry Comparisons

2.3.2. Between-Ancestry Comparisons

2.4. Frequencies of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations Across Age, Ancestry, and Treatment Groups

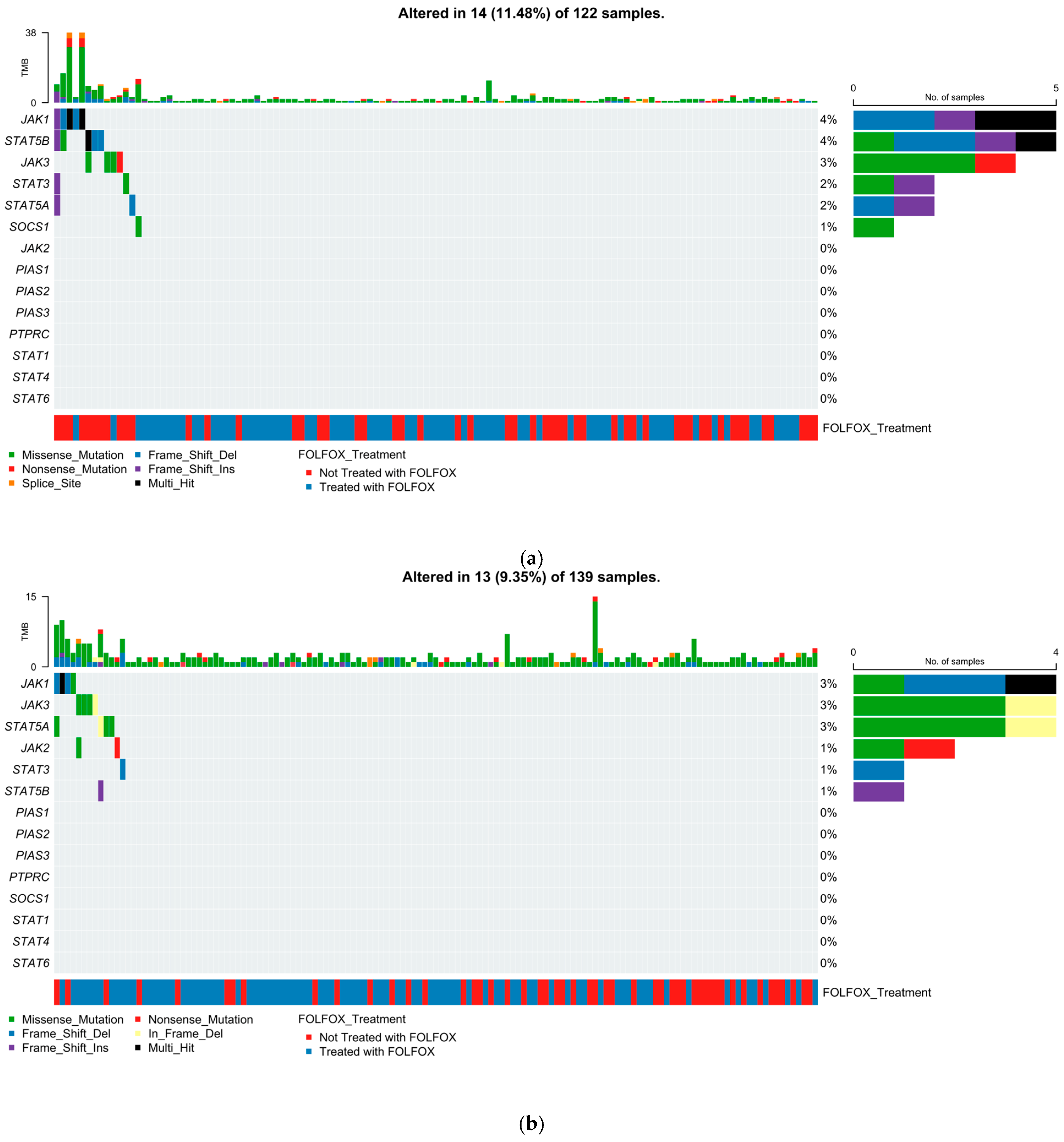

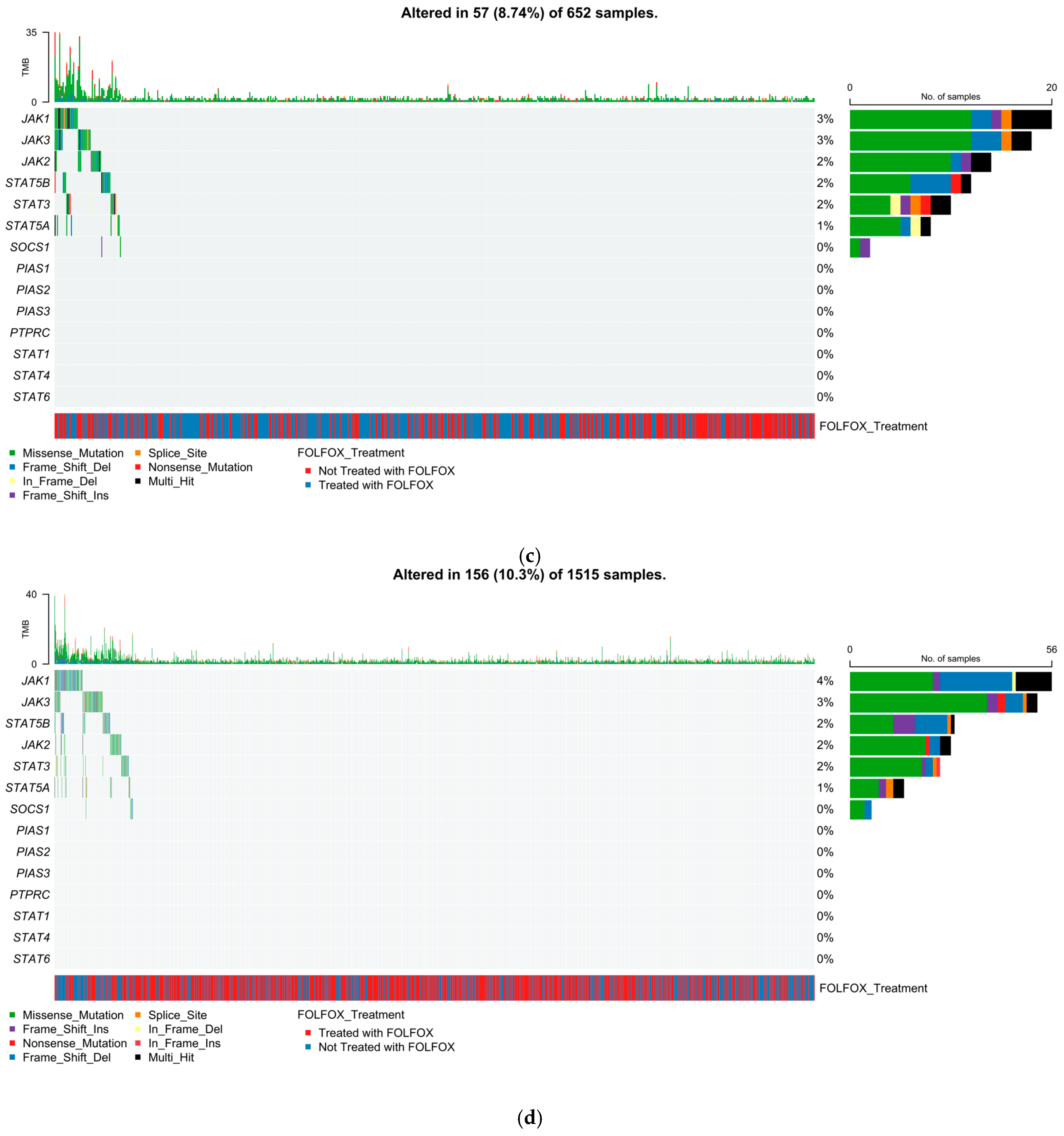

2.5. Mutational Landscape of the JAK-STAT Pathway

2.5.1. Early-Onset H/L CRC

2.5.2. Late-Onset H/L CRC

2.5.3. Early-Onset NHW CRC

2.5.4. Late-Onset NHW CRC

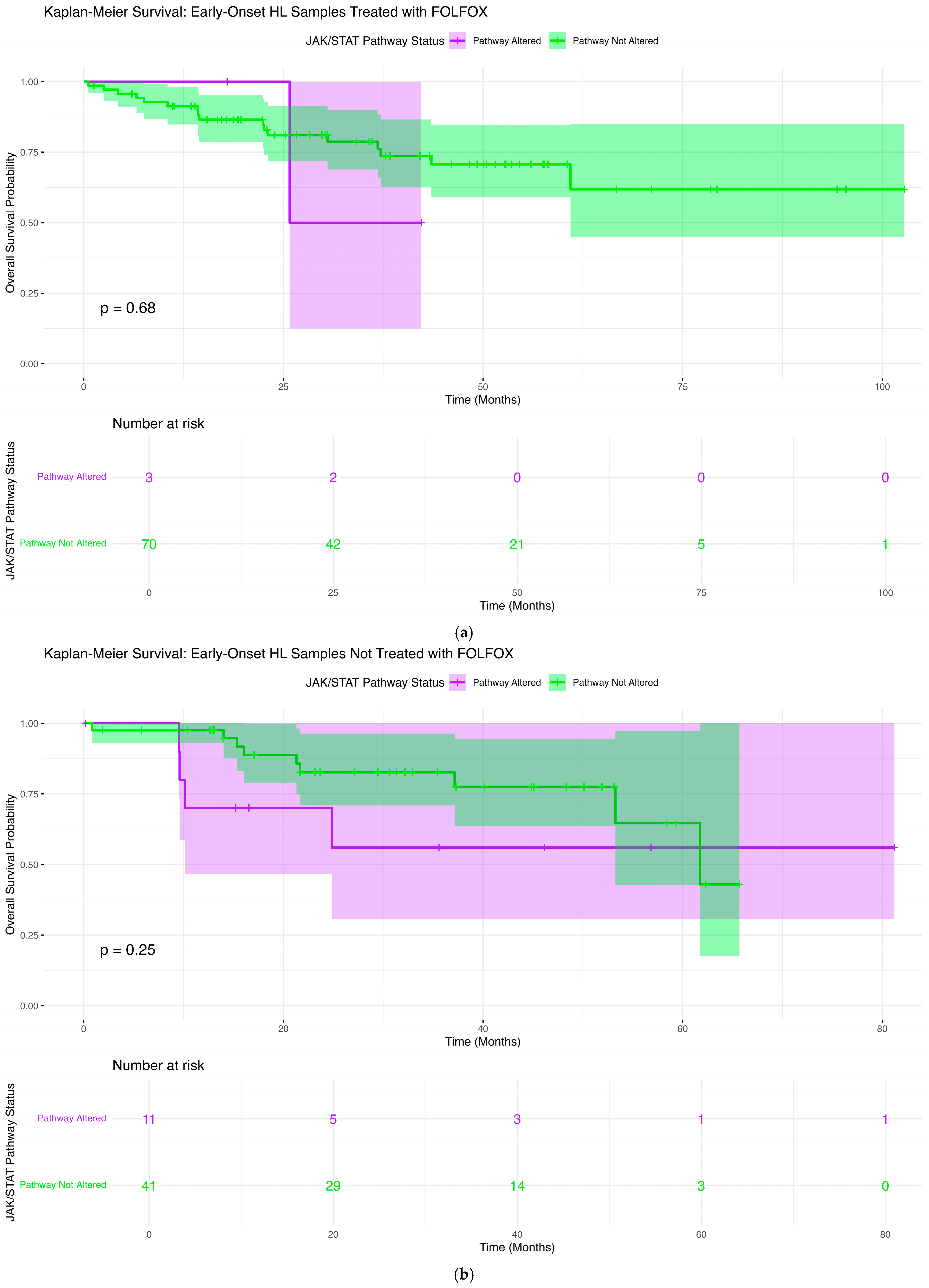

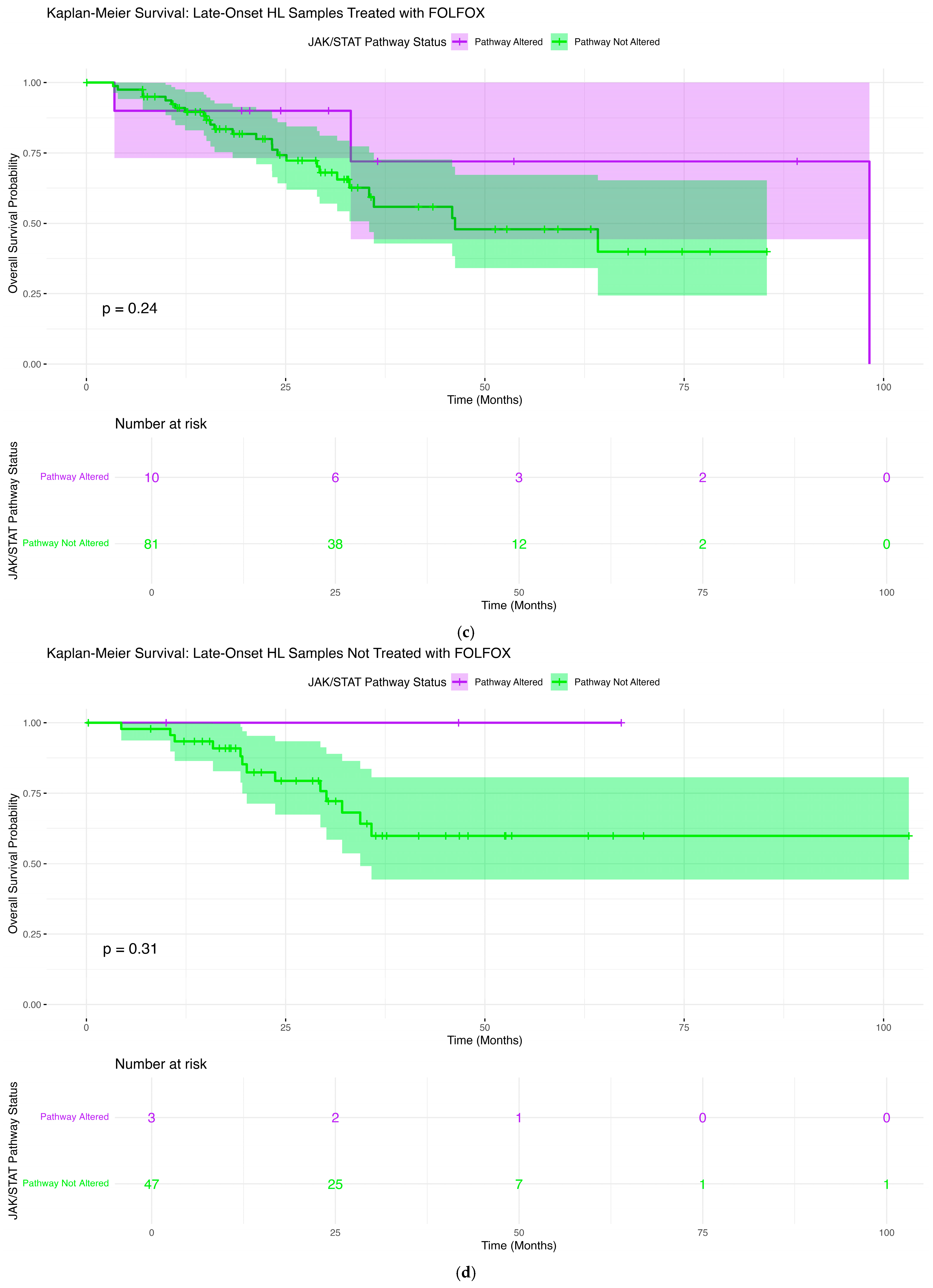

2.6. Overall Survival Patterns Associated with JAK-STAT Pathway Mutations Across Clinical and Demographic Strata

2.6.1. Early-Onset H/L Patients Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.2. Early-Onset H/L Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.3. Late-Onset H/L Patients Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.4. Late-Onset H/L Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

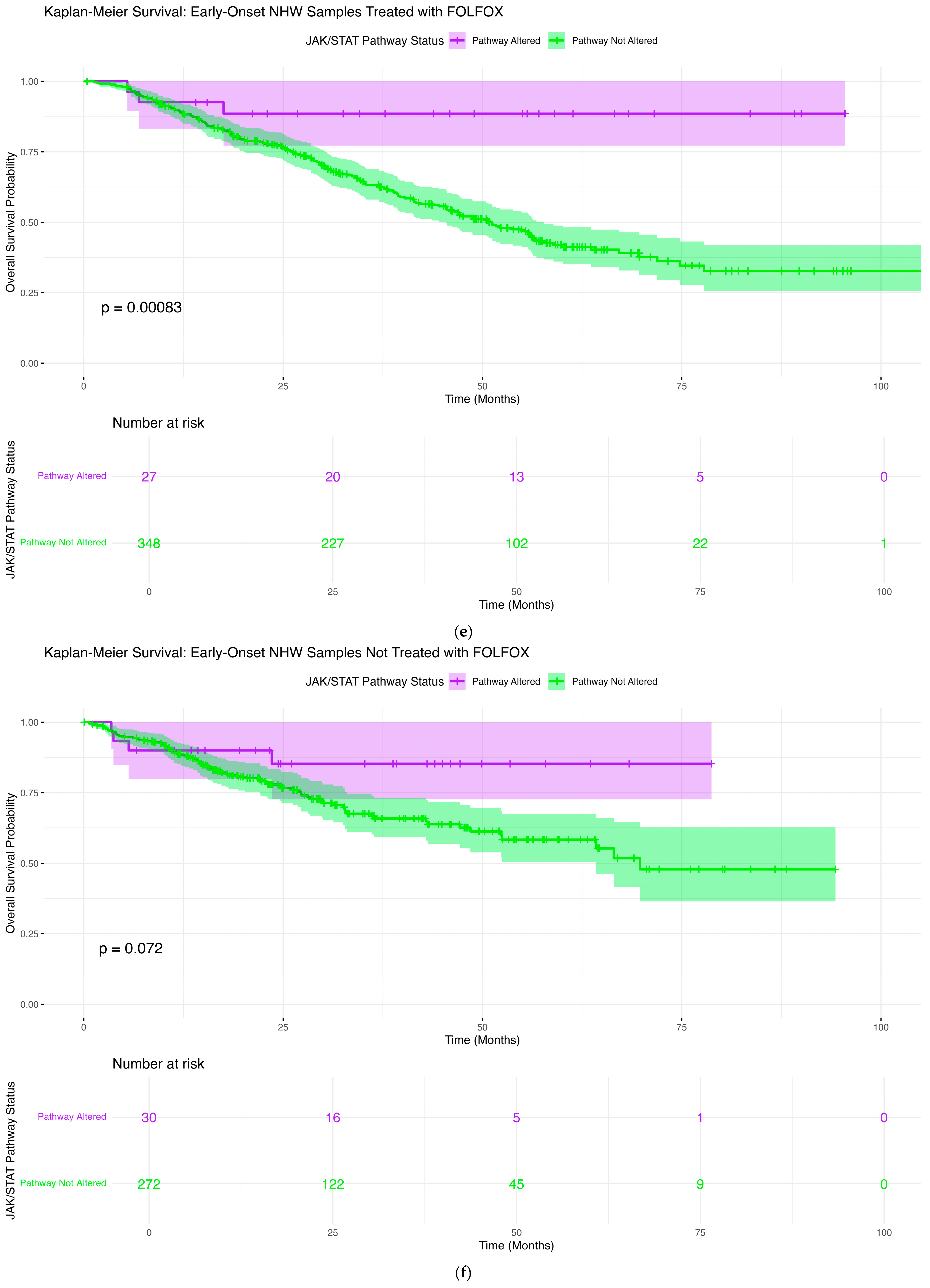

2.6.5. Early-Onset NHW Patients Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.6. Early-Onset NHW Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.7. Late-Onset NHW Patients Treated with FOLFOX

2.6.8. Late-Onset NHW Patients Not Treated with FOLFOX

2.7. AI-Driven Exploratory Interrogation of Clinical-Genomic Data Prior to Formal Statistical Testing

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of Key Findings

3.2. Biological Implications of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations

3.3. Ancestry-Specific Genomic Patterns and Treatment Context

3.4. Implications for FOLFOX Response and Prognostic Stratification

3.5. AI-HOPE-JAK-STAT as an Enabling Technology

3.6. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources and Cohort Construction

4.2. Case Selection

4.3. Classification of Disproportionately Affected Populations

4.4. Identification of FOLFOX-Treated and Non-FOLFOX Groups

4.5. JAK-STAT Pathway Gene Set Compilation and Molecular Alteration Definition

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. AI-HOPE-Enabled Data Harmonization, Pathway Interrogation, and Analytic Refinement

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monge, C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Ethnicity-Specific Molecular Alterations in MAPK and JAK/STAT Pathways in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, E.W.; Waldrup, B.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Decoding the JAK-STAT Axis in Colorectal Cancer with AI-HOPE-JAK-STAT: A Conversational Artificial Intelligence Approach to Clinical-Genomic Integration. Cancers 2025, 17, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.G.; Karlitz, J.J.; Yen, T.; Lieu, C.H.; Boland, C.R. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santucci, C.; Mignozzi, S.; Alicandro, G.; Pizzato, M.; Malvezzi, M.; Negri, E.; Jha, P.; La Vecchia, C. Trends in cancer mortality under age 50 in 15 upper-middle and high-income countries. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2025, 117, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garcia, S.; Pruitt, S.L.; Singal, A.G.; Murphy, C.C. Colorectal cancer incidence among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sinicrope, F.A. Increasing Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Huo, J. TP53 Is a Potential Target of Juglone Against Colorectal Cancer: Based on a Combination of Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and In Vitro Experiments. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, I.; Kim, S.; Sridhar, S.; Basha, R. Colorectal Cancer: An Emphasis on Factors Influencing Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2020, 25, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.Y.; Thrift, A.P.; Zarrin-Khameh, N.; Wichmann, A.; Armstrong, G.N.; Thompson, P.A.; Bondy, M.L.; Musher, B.L. Rising Incidence of Colorectal Cancer Among Young Hispanics in Texas. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhandari, A.; Woodhouse, M.; Gupta, S. Colorectal cancer is a leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality among adults younger than 50 years in the USA: A SEER-based analysis with comparison to other young-onset cancers. J. Investig. Med. 2017, 65, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torres, T.; Arellano Villanueva, E.; Alsabawi, Y.; Fofana, D.; Tripathi, M.K. Unraveling Early Onset Disparities and Determinants: An Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Outcomes and Trends in Texas. Cureus 2025, 17, e83124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, H.E.; Cho, N.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, G.H. Characterisation of PD-L1-positive subsets of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, X.; Schardey, J.; Wirth, U.; Heinrich, K.; Massiminio, L.; Cavestro, G.M.; Neumann, J.; Bazhin, A.V.; Werner, J.; et al. Molecular characteristics of microsatellite stable early-onset colorectal cancer as predictors of prognosis and immunotherapeutic response. npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mauri, G.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Russo, A.G.; Marsoni, S.; Bardelli, A.; Siena, S. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lieu, C.H.; Golemis, E.A.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Newberg, J.; Hemmerich, A.; Connelly, C.; Messersmith, W.A.; Eng, C.; Eckhardt, S.G.; Frampton, G.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Landscapes in Early and Later Onset Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5852–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Antelo, M.; Balaguer, F.; Shia, J.; Shen, Y.; Hur, K.; Moreira, L.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Bujanda, L.; Giraldez, M.D.; Takahashi, M.; et al. A high degree of LINE-1 hypomethylation is a unique feature of early-onset colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lim, H.I.; Kim, G.Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, K.; Ko, S.G. Uncovering the anti-cancer mechanism of cucurbitacin D against colorectal cancer through network pharmacology and molecular docking. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, C.; Zhu, R.; Dai, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, G.; Tao, K.; Xu, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, G. TIMP-2 Modulates 5-Fu Resistance in Colorectal Cancer Through Regulating JAK-STAT Signalling Pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, J.; Han, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Li, X. LncRNA FAM30A Suppresses Proliferation and Metastasis of Colorectal Carcinoma by Blocking the JAK-STAT Signalling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, D.E.; O’Keefe, R.A.; Grandis, J.R. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xue, J.; Liao, L.; Yin, F.; Kuang, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y. LncRNA AB073614 induces epithelial- mesenchymal transition of colorectal cancer cells via regulating the JAK/STAT3 pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 21, 849–858, Erratum in Cancer Biomark. 2021, 32, 569. https://doi.org/10.3233/CBM-219780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarino, A.V.; Kanno, Y.; Ferdinand, J.R.; O’Shea, J.J. Mechanisms of Jak/STAT signaling in immunity and disease. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nobel, Y.R.; Stier, K.; Krishnareddy, S. STAT signaling in the intestine. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 361, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, N.; Liongue, C.; Ward, A.C. STAT proteins: A kaleidoscope of canonical and non-canonical functions in immunity and cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sabaawy, H.E.; Ryan, B.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Pine, S.R. JAK/STAT of all trades: Linking inflammation with cancer development, tumor progression and therapy resistance. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farooqi, A.A.; de la Roche, M.; Djamgoz, M.B.A.; Siddik, Z.H. Overview of the oncogenic signaling pathways in colorectal cancer: Mechanistic insights. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 58, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, P.R.; Mo, J.H.; Harris, A.R.; Lee, J.; Raz, E. STAT3: An Anti-Invasive Factor in Colorectal Cancer? Cancers 2014, 6, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, H.; Ren, G.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Gong, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, H.; Shen, J.; Zhu, L.; et al. Aberrantly expressed Fra-1 by IL-6/STAT3 transactivation promotes colorectal cancer aggressiveness through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pennel, K.A.F.; Hatthakarnkul, P.; Wood, C.S.; Lian, G.Y.; Al-Badran, S.S.F.; Quinn, J.A.; Legrini, A.; Inthagard, J.; Alexander, P.G.; van Wyk, H.; et al. JAK/STAT3 represents a therapeutic target for colorectal cancer patients with stromal-rich tumors. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, A.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Tang, E.; Jiang, H. Comparative mutational analysis of distal colon cancer with rectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, N.; Yue, W.; Jiao, B.; Cheng, D.; Wang, J.; Liang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, K.; Liu, J.; et al. Unveiling prognostic value of JAK/STAT signaling pathway related genes in colorectal cancer: A study of Mendelian randomization analysis. Infect. Agents Cancer 2025, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tordjman, M.; Bolger, I.; Yuce, M.; Restrepo, F.; Liu, Z.; Dercle, L.; McGale, J.; Meribout, A.L.; Liu, M.M.; Beddok, A.; et al. Large Language Models in Cancer Imaging: Applications and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shanwetter Levit, N.; Saban, M. When investigator meets large language models: A qualitative analysis of cancer patient decision-making journeys. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buvat, I.; Weber, W. Nuclear Medicine from a Novel Perspective: Buvat and Weber Talk with OpenAI’s ChatGPT. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visvikis, D.; Lambin, P.; Beuschau Mauridsen, K.; Hustinx, R.; Lassmann, M.; Rischpler, C.; Shi, K.; Pruim, J. Application of artificial intelligence in nuclear medicine and molecular imaging: A review of current status and future perspectives for clinical translation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 4452–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, J.; Yang, P.; Xue, S.; Sharma, B.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Wang, F.; Beaty, K.A.; Dehan, E.; Parikh, B. Translating cancer genomics into precision medicine with artificial intelligence: Applications, challenges and future perspectives. Hum. Genet. 2019, 138, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akimoto, N.; Ugai, T.; Zhong, R.; Hamada, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Giannakis, M.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Ng, K.; Ogino, S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer—A call to action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carranza, F.G.; Diaz, F.C.; Ninova, M.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Current state and future prospects of spatial biology in colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1513821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elhanani, O.; Ben-Uri, R.; Keren, L. Spatial profiling technologies illuminate the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilento, M.A.; Sweeney, C.J.; Butler, L.M. Spatial transcriptomics in cancer research and potential clinical impact: A narrative review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. STAT3 regulates 5-Fu resistance in human colorectal cancer cells by promoting Mcl-1-dependent cytoprotective autophagy. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 2293–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polak, K.L.; Chernosky, N.M.; Smigiel, J.M.; Tamagno, I.; Jackson, M.W. Balancing STAT Activity as a Therapeutic Strategy. Cancers 2019, 11, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiong, H.; Zhang, Z.G.; Tian, X.Q.; Sun, D.F.; Liang, Q.C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Lu, R.; Chen, Y.X.; Fang, J.Y. Inhibition of JAK1, 2/STAT3 signaling induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and reduces tumor cell invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Swierz, M.J.; Storman, D.; Mitus, J.W.; Hetnal, M.; Kukielka, A.; Szlauer-Stefanska, A.; Pedziwiatr, M.; Wolff, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Bala, M.M. Transarterial (chemo)embolisation versus systemic chemotherapy for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 8, CD012757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Artificial Intelligence-Guided Molecular Determinants of PI3K Pathway Alterations in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Among High-Risk Groups Receiving FOLFOX. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.W.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. AI-HOPE: An AI-driven conversational agent for enhanced clinical and genomic data integration in precision medicine research. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Clinical Feature | H/L Cohort n (%) | NHW Cohort n (%) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Disease Onset | |||

| EOCRC Treated with FOLFOX | 73 (27.4%) | 375 (16.7%) | 448 |

| EOCRC Not Treated with FOLFOX | 52 (19.5%) | 302 (13.4%) | 354 |

| LOCRC Treated with FOLFOX | 91 (34.2%) | 919 (40.9%) | 1010 |

| LOCRC Not Treated with FOLFOX | 50 (18.8%) | 653 (29.0%) | 703 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 158 (59.4%) | 1267 (56.3%) | 1425 |

| Female | 108 (40.6%) | 982 (43.7%) | 1090 |

| Sample type | |||

| Primary Tumor | 266 (100.0%) | 2249 (100.0%) | 2515 |

| State at Diagnosis | |||

| Stage 1–3 | 156 (58.6%) | 1236 (55.0%) | 1392 |

| Stage 4 | 108 (40.6%) | 1005 (44.7%) | 1113 |

| NA | 2 (0.8%) | 8 (0.4%) | 10 |

| Cancer Type | |||

| Colon Adenocarcinoma | 164 (61.7%) | 1328 (59.0%) | 1492 |

| Rectal Adenocarcinoma | 64 (24.1%) | 646 (28.7%) | 710 |

| Colorectal Adenocarcinoma | 38 (14.3%) | 275 (12.2%) | 313 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Spanish NOS/Hispanic NOS/Latino NOS | 230 (86.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 230 |

| Mexican (includes Chicano) | 30 (11.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 30 |

| Hispanic Category 2 | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 |

| Hispanic Category 1 | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 |

| Other Spanish/Hispanic | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 0 (0.0%) | 2249 (100.0%) | 2249 |

| (a) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 42 (36–47) | 40 (34–43) | 0.05411 | 59 (54–66) | 62 (56–70) | 0.04865 |

| Median Mutation Count | 7 (5–8) | 7 (5–20) | 0.09735 | 8 (6–9) [NA=1] | 7 (5.25–9) | 0.6507 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 6.3 (4.5–7.8) [NA = 15] | 5.5 (3.4–8.3) [NA = 2] | 0.1719 | 6.1 (4.9–7.8) [NA = 10] | 6.9 (5.6–9.0) [NA = 2] | 0.04389 |

| Median FGA | 0.18 (0.03–0.27) [NA = 6] | 0.19 (0.03–0.29) | 0.7661 | 0.15 (0.06–0.25) [NA = 7] | 0.21 (0.04–0.3) [NA = 2] | 0.5464 |

| STAT5B Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (9.6%) | 0.01108 | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 |

| Absent | 73 (100.0%) | 47 (90.4%) | 90 (98.9%) | 90 (98.9%) | ||

| (b) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 43 (37–48) | 44 (38–47) | 0.5646 | 63 (57–69) | 66 (57–74) | 4.146 × 10−7 |

| Median Mutation Count | 6 (5–8) [NA = 4] | 7 (5–9) [NA = 2] | 0.1258 | 7 (5–9) [NA = 10] | 8 (6–12) [NA = 3] | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 5.7 (4.1–6.9) | 5.7 (4.1–7.8) | 0.4214 | 6.1 (4.3–8.2) | 6.6 (4.9–10.4) | 0.0002854 |

| Median FGA | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) [NA = 4] | 0.15 (0.04–0.23) [NA = 2] | 0.5589 | 0.16 (0.06–0.28) [NA = 6] | 0.15 (0.05–0.27) [NA = 5] | 0.1929 |

| JAK3 Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 4 (1.1%) | 14 (4.6%) | 0.006502 | 14 (2.6%) | 28 (4.3%) | 0.9409 |

| Absent | 371 (98.9%) | 288 (95.4%) | 288 (97.4%) | 625 (95.7%) | ||

| (c) | ||||||

| Clinical Feature | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| Median Diagnosis Age (IQR) | 42 (36–47) | 43 (37–48) | 0.08467 | 40 (34–43) | 44 (38–47) | 0.0006016 |

| Median Mutation Count | 7 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) [NA = 4] | 0.942 | 7 (5–20) | 7 (5–9) [NA = 2] | 0.2601 |

| Median TMB (IQR) | 6.3 (4.5–7.8) [NA = 15] | 5.7 (4.1–6.9) | 0.05806 | 5.5 (3.4–8.3) [NA = 2] | 5.7 (4.1–7.8) | 0.5732 |

| Median FGA | 0.18 (0.03–0.27) [NA = 6] | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) [NA = 4] | 0.5556 | 0.19 (0.03–0.29) | 0.15 (0.04–0.23) [NA = 2] | 0.3612 |

| STAT5B Mutation | ||||||

| Present | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.3%) | 1 | 5 (9.6%) | 7 (2.3%) | 0.01994 |

| Absent | 73 (100.0%) | 370 (98.7%) | 47 (90.4%) | 295 (97.7%) | ||

| (a) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Present | 3 (4.1%) | 11 (21.2%) | 0.003851 | 10 (11.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0.3811 |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Absent | 70 (95.9%) | 41 (78.8%) | 81 (89.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | ||

| (b) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Present | 27 (7.2%) | 30 (9.9%) | 0.9979 | 69 (7.5%) | 87 (13.3%) | 0.0002036 |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Absent | 348 (92.8%) | 372 (123.2%) | 850 (92.5%) | 566 (86.7%) | ||

| (c) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Early-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Early-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Present | 3 (4.1%) | 27 (7.2%) | 0.4472 | 11 (21.2%) | 30 (9.9%) | 0.002843 |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Absent | 70 (95.9%) | 348 (92.8%) | 41 (78.8%) | 372 (123.2%) | ||

| (d) | ||||||

| Pathway Alterations | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value | Late-Onset Hispanic/Latino Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | Late-Onset NHW Not Treated with FOLFOX n (%) | p-value |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Present | 10 (11.0%) | 69 (7.5%) | 0.3296 | 3 (6.0%) | 87 (13.3%) | 0.1857 |

| JAK/STAT Alterations Absent | 81 (89.0%) | 850 (92.5%) | 47 (94.0%) | 566 (86.7%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diaz, F.C.; Waldrup, B.; Carranza, F.G.; Manjarrez, S.; Velazquez-Villarreal, E. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Molecular Profiling of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010479

Diaz FC, Waldrup B, Carranza FG, Manjarrez S, Velazquez-Villarreal E. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Molecular Profiling of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010479

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaz, Fernando C., Brigette Waldrup, Francisco G. Carranza, Sophia Manjarrez, and Enrique Velazquez-Villarreal. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Molecular Profiling of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010479

APA StyleDiaz, F. C., Waldrup, B., Carranza, F. G., Manjarrez, S., & Velazquez-Villarreal, E. (2026). Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Molecular Profiling of JAK-STAT Pathway Alterations in FOLFOX-Treated Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010479