Molecular Basis of Persister Awakening and Lag-Phase Recovery in Escherichia coli After Antibiotic Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

Fundamental Concepts, Clinical Relevance of Persistence, and the Role of Stochasticity and Stress in Dormancy Induction

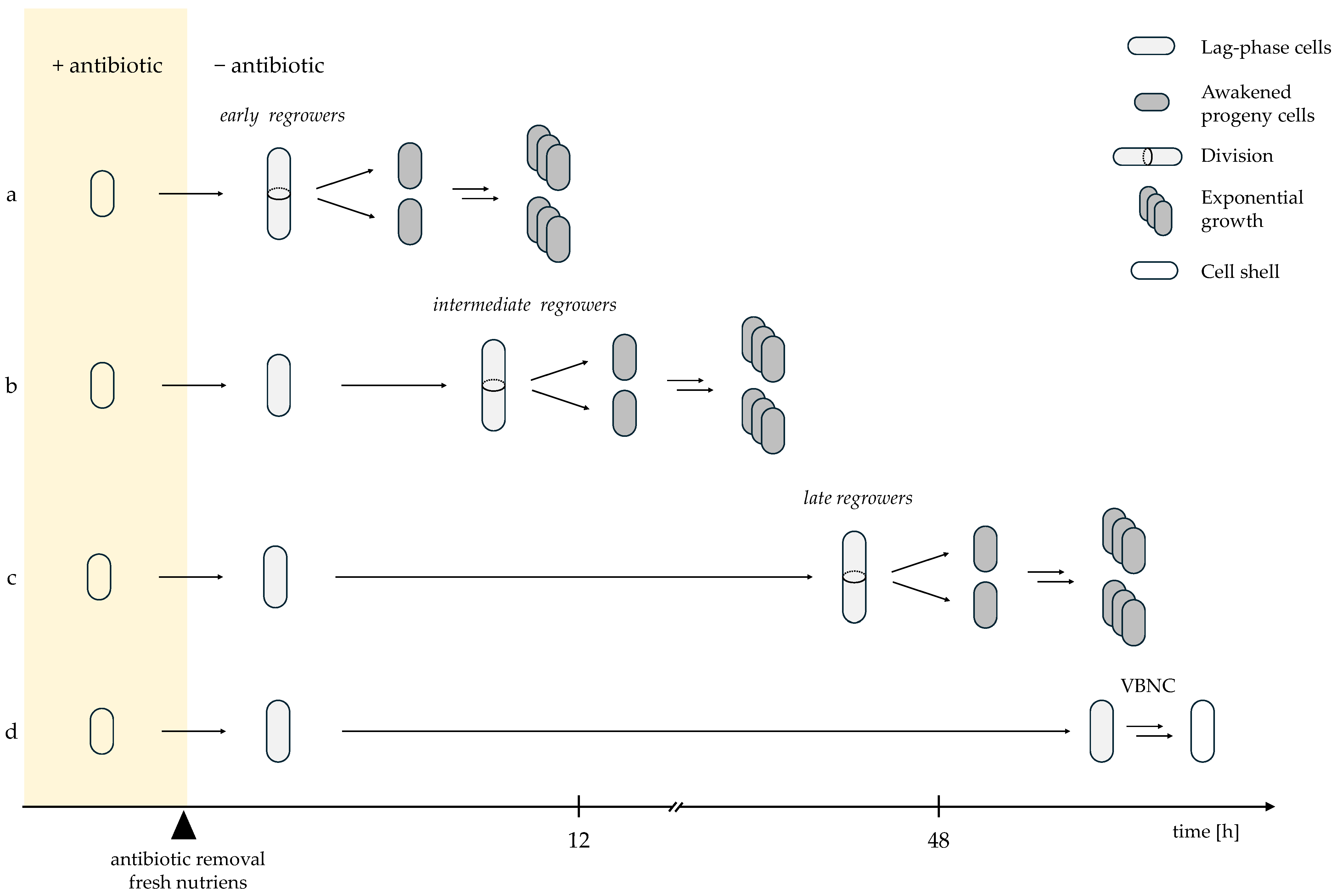

2. Heterogeneity in Persister Awakening Dynamics

Diverse Recovery Timings Reveal Graded Survival Outcomes After Antibiotic Exposure

3. Nutrient-Sensing and Signal-Driven Control of Resuscitation

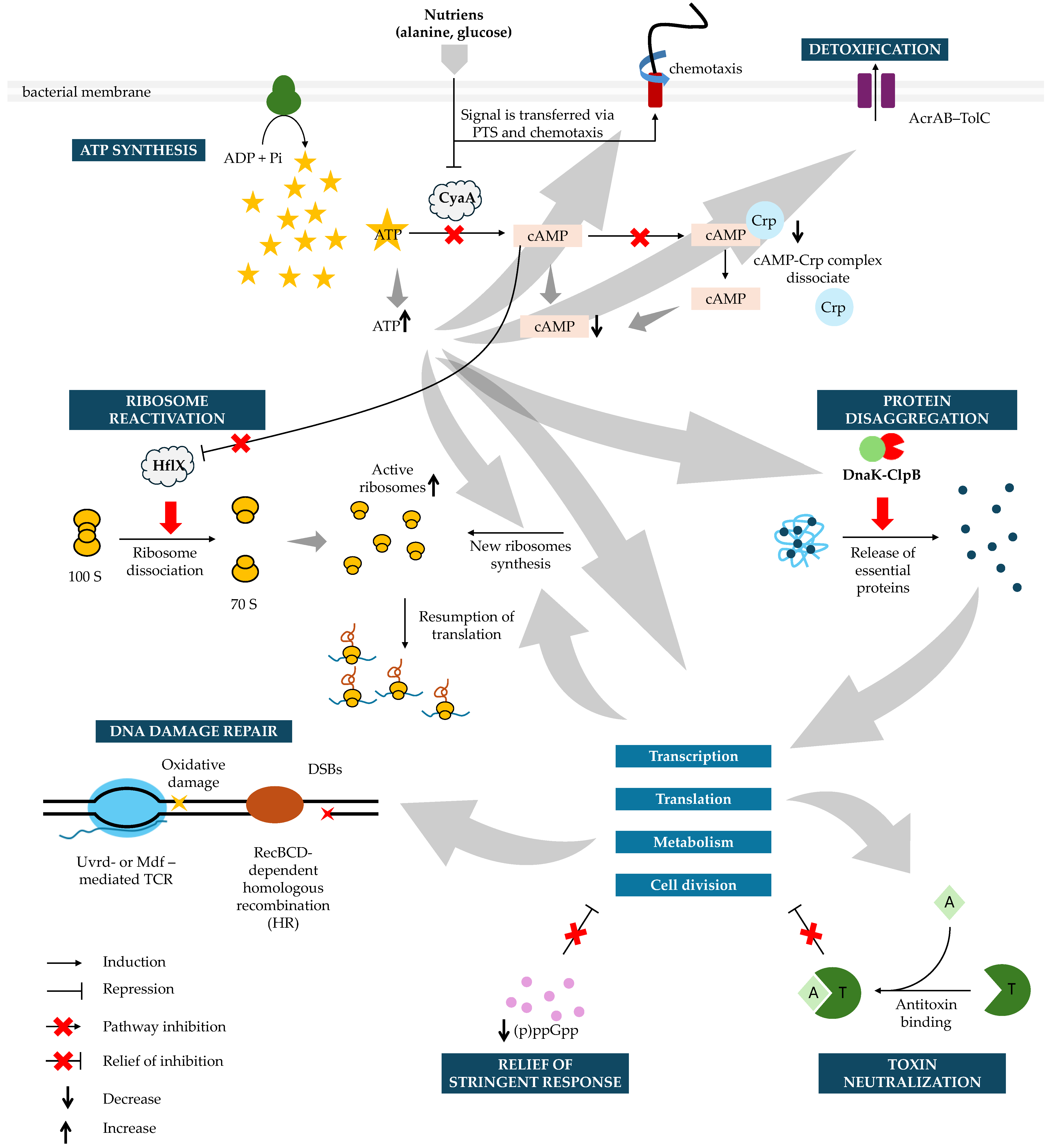

Persister Awakening Is Actively Triggered by Environmental Cues Rather than Random Activation

4. Energy Status as a Driver of Dormancy Entry and Awakening

ATP Depletion Induces Persistence, Whereas ATP and cAMP Dynamics Govern Recovery

5. Ribosome Availability as a Key Modulator of Awakening Speed

Pre-Existing and Newly Synthesized Ribosomes Determine the Success of Recovery

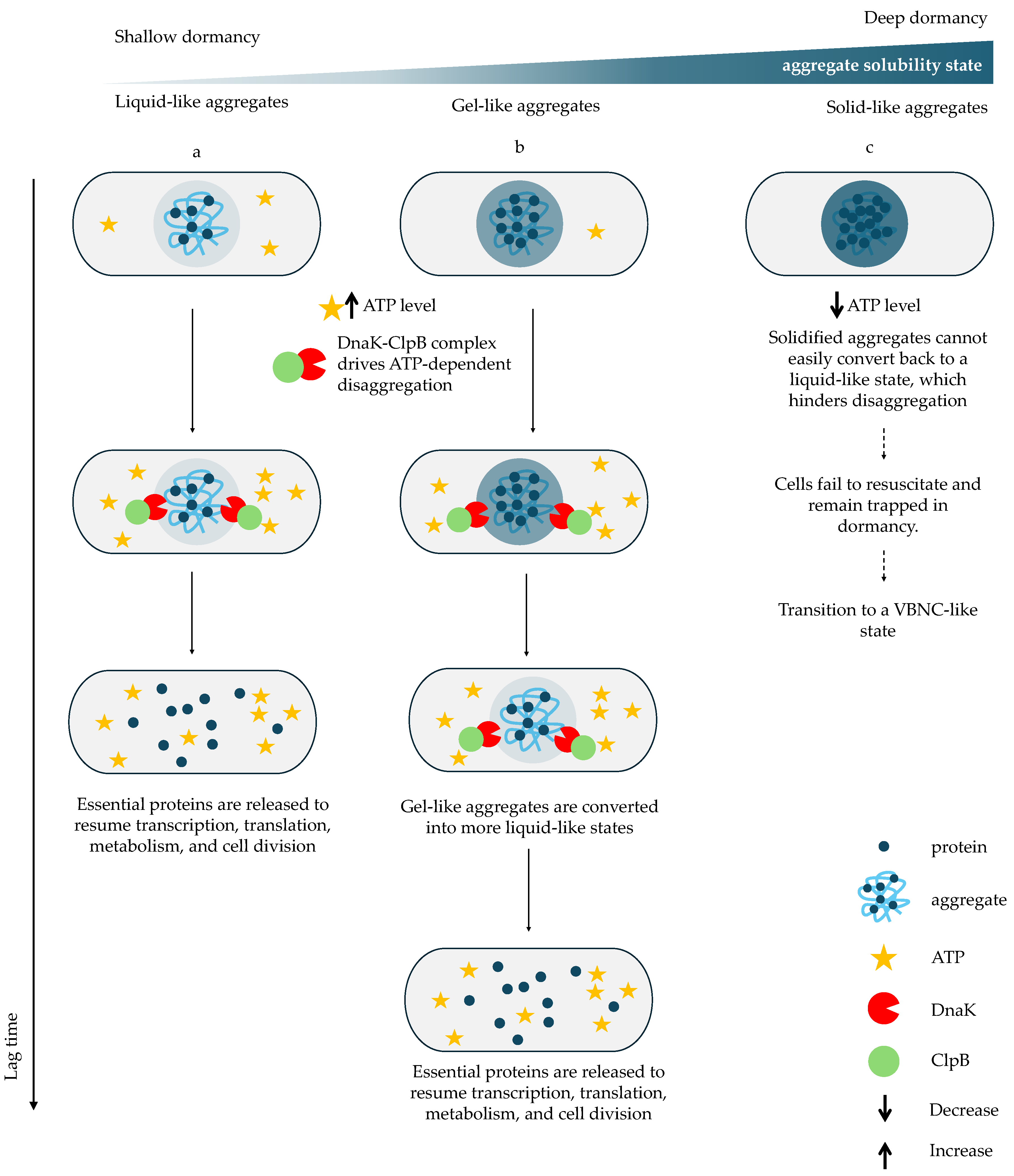

6. Protein Aggregation as a Molecular Signature of Dormancy and a Barrier to Resuscitation

Proteome Condensation Stabilizes Persistence but Requires ATP-Dependent Disaggregation for Growth Restart

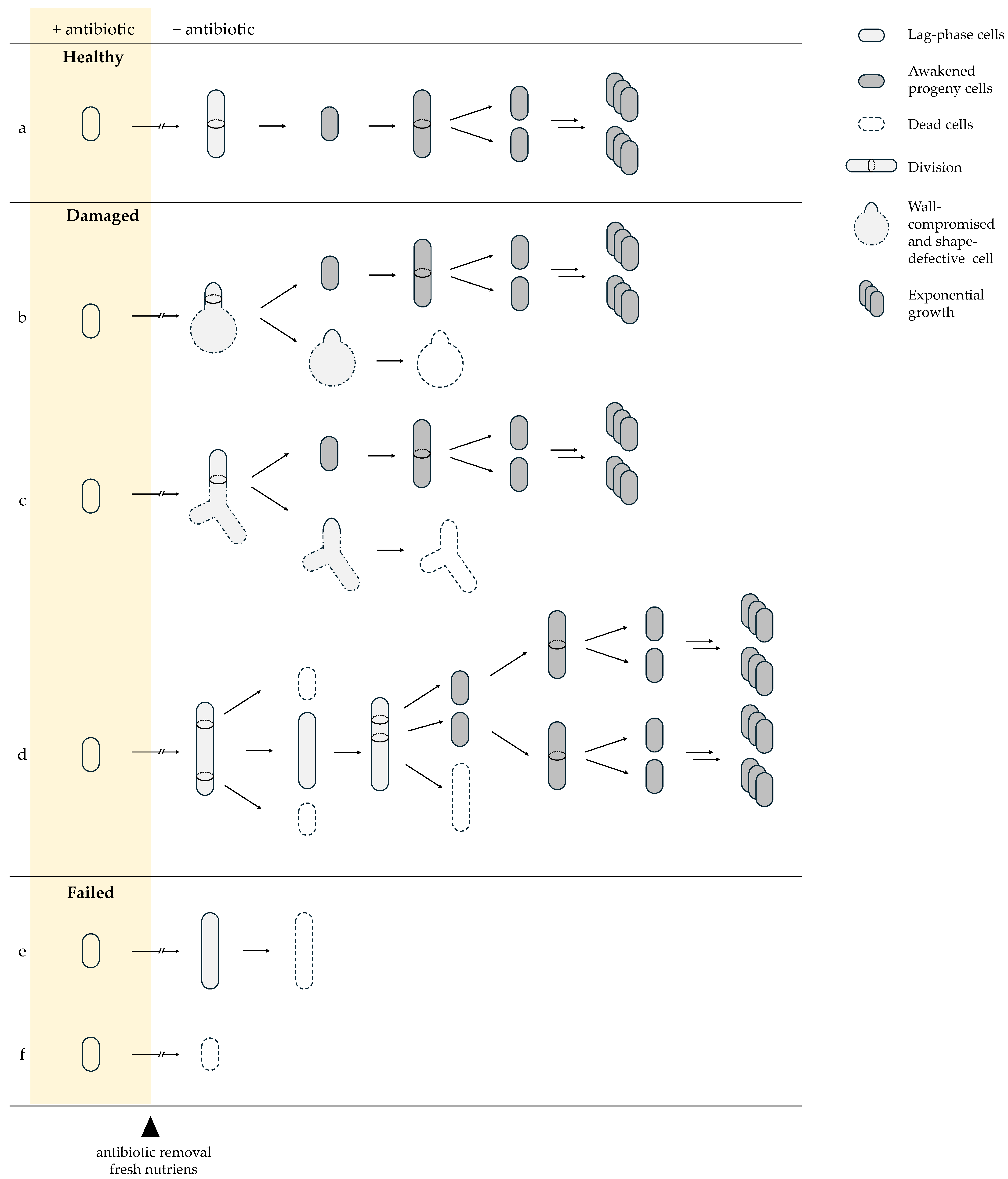

7. Antibiotic-Induced Damage Determines Recovery Trajectories

β-Lactam and Fluoroquinolone Exposure Impose Distinct Molecular Lesions Shaping Awakening Outcomes

8. Efflux-Mediated Detoxification as an Essential Requirement for Post-Antibiotic Regrowth

Clearance of Residual Intracellular Antibiotics Limits Lag Time and Enables Cell Wall Synthesis

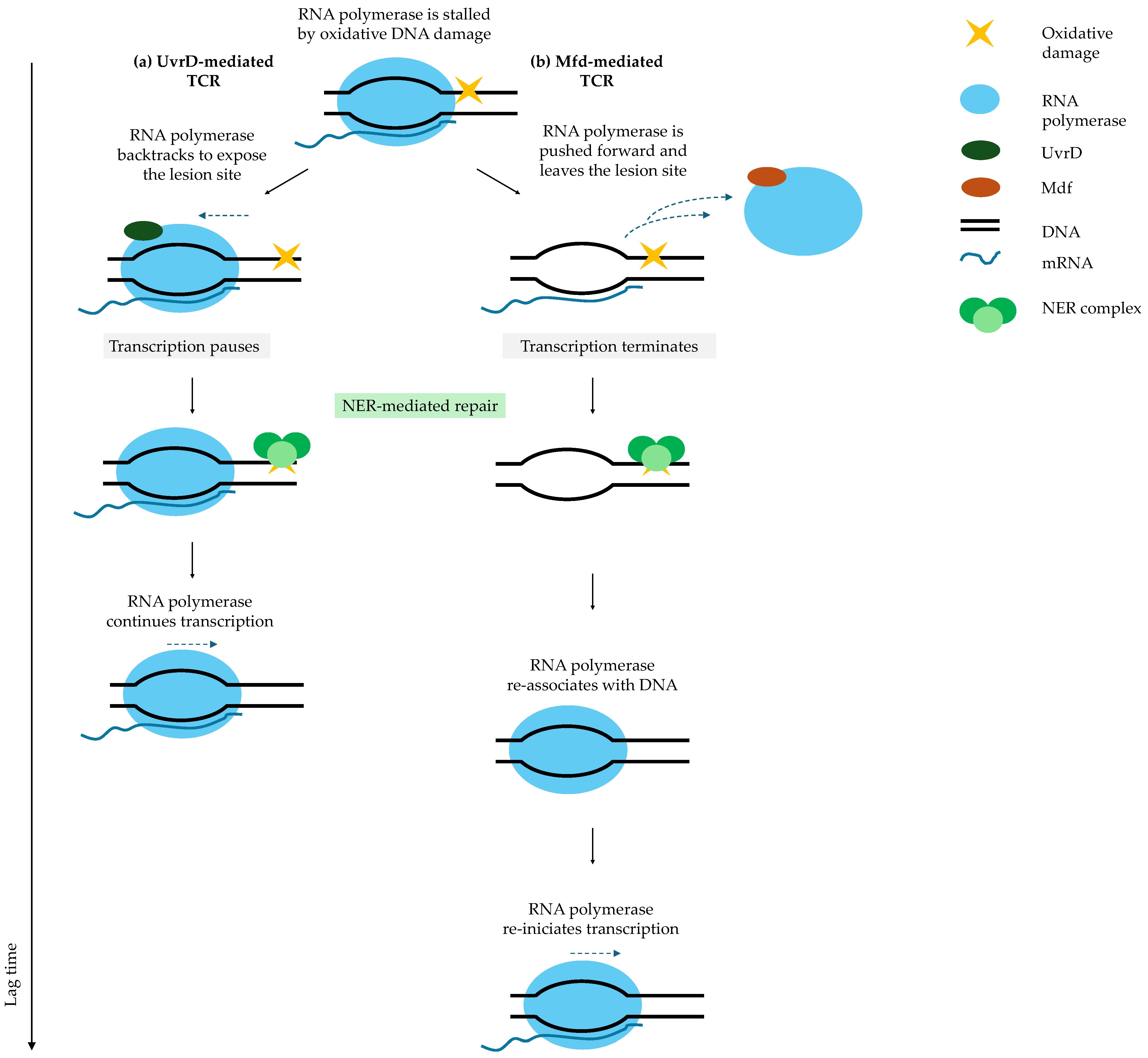

9. DNA Repair Pathways as Central Determinants of Fluoroquinolone Persister Recovery

SOS-Driven Homologous Recombination and Transcription-Coupled Repair Govern Successful Resuscitation

10. Induction Pathways Impose Indirect Constraints on Persister Awakening

Stringent Response and Toxin–Antitoxin Systems Condition, but Do Not Dictate, Lag-Phase Duration

11. Conclusions

Persister Cell Survival Becomes Clinically Relevant Only When It Is Followed by Successful Physiological Reactivation and the Formation of Viable Progeny

12. Future Perspectives and Clinical Relevance

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darby, E.M.; Trampari, E.; Siasat, P.; Gaya, M.S.; Alav, I.; Webber, M.A.; Blair, J.M.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Revisited. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 280–295, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q.; Helaine, S.; Lewis, K.; Ackermann, M.; Aldridge, B.; Andersson, D.I.; Brynildsen, M.P.; Bumann, D.; Camilli, A.; Collins, J.J.; et al. Definitions and Guidelines for Research on Antibiotic Persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 441–448, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Persister Cells, Dormancy and Infectious Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q.; Merrin, J.; Chait, R.; Kowalik, L.; Leibler, S. Bacterial Persistence as a Phenotypic Switch. Science 2004, 305, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewachter, L.; Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J. Bacterial Heterogeneity and Antibiotic Survival: Understanding and Combatting Persistence and Heteroresistance. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenreich, W.; Rudel, T.; Heesemann, J.; Goebel, W. Link Between Antibiotic Persistence and Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 900848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Łupkowska, A.; Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Laskowska, E. Antibiotic Heteroresistance in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Yang, K. Reversing Antibiotic Resistance Caused by Mobile Resistance Genes of High Fitness Cost. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, R.; Yuan, B.; Yang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Q. Heterogeneous Subpopulations in Escherichia coli Strains Acquire Adaptive Resistance to Imipenem Treatment through Rapid Transcriptional Regulation. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1563316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauvart, M.; de Groote, V.N.; Michiels, J. Role of Persister Cells in Chronic Infections: Clinical Relevance and Perspectives on Anti-Persister Therapies. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yew, W.W.; Barer, M.R. Targeting Persisters for Tuberculosis Control. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, J.; Lewis, K. Noise in a Metabolic Pathway Leads to Persister Formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e02948-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrey, H.L.; Keren, I.; Via, L.E.; Lee, J.S.; Lewis, K. High Persister Mutants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, L.R.; Burns, J.L.; Lory, S.; Lewis, K. Emergence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains Producing High Levels of Persister Cells in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 6191–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, I.; Risener, C.J.; Falk, K.; Northington, G.; Quave, C.L. Bacterial Persistence in Urinary Tract Infection Among Postmenopausal Population. Urogynecology 2024, 30, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.O.; Flores, C.; Williams, C.; Flusberg, D.A.; Marr, E.E.; Kwiatkowska, K.M.; Charest, J.L.; Isenberg, B.C.; Rohn, J.L. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: A Mystery in Search of Better Model Systems. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 691210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Brown, A.V.; Matluck, N.E.; Hu, L.T.; Lewis, K. Borrelia Burgdorferi, the Causative Agent of Lyme Disease, Forms Drug-Tolerant Persister Cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4616–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeaux, D.; Ghigo, J.-M.; Beloin, C. Biofilm-Related Infections: Bridging the Gap between Clinical Management and Fundamental Aspects of Recalcitrance toward Antibiotics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2014, 78, 510–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helaine, S.; Cheverton, A.M.; Watson, K.G.; Faure, L.M.; Matthews, S.A.; Holden, D.W. Internalization of Salmonella by Macrophages Induces Formation of Nonreplicating Persisters. Science 2014, 343, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Gollan, B.; Helaine, S. Persistent Bacterial Infections and Persister Cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windels, E.M.; Michiels, J.E.; Fauvart, M.; Wenseleers, T.; Van den Bergh, B.; Michiels, J. Bacterial Persistence Promotes the Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance by Increasing Survival and Mutation Rates. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldini, M.; Mostowy, R.; Bonhoeffer, S.; Ackermann, M. Evolution of Stress Response in the Face of Unreliable Environmental Signals. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Kærn, M. A Chance at Survival: Gene Expression Noise and Phenotypic Diversification Strategies. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 71, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuse, S.; Shan, Y.; Canas-Duarte, S.J.; Bakshi, S.; Sun, W.S.; Mori, H.; Paulsson, J.; Lewis, K. Bacterial Persisters Are a Stochastically Formed Subpopulation of Low-Energy Cells. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.W.; Valenta, J.A.; Benedik, M.J.; Wood, T.K. Arrested Protein Synthesis Increases Persister-like Cell Formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Brown Gandt, A.; Rowe, S.E.; Deisinger, J.P.; Conlon, B.P.; Lewis, K. ATP-Dependent Persister Formation in Escherichia coli. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmaerts, D.; Windels, E.M.; Verstraeten, N.; Michiels, J. General Mechanisms Leading to Persister Formation and Awakening. Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, R.H.; Padberg, F.T.; Smith, S.M.; Tan, E.N.; Cherubin, C.E. Bactericidal Effects of Antibiotics on Slowly Growing and Nongrowing Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 1824–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaldalu, N.; Tenson, T. Slow Growth Causes Bacterial Persistence. Sci. Signal 2019, 12, eaay1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, H.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Y. Bacterial Persisters: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Development. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Persisters, Persistent Infections and the Yin-Yang Model. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2014, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orman, M.A.; Brynildsen, M.P. Dormancy Is Not Necessary or Sufficient for Bacterial Persistence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõers, A.; Tenson, T. Growth Resumption from Stationary Phase Reveals Memory in Escherichia coli Cultures. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõers, A.; Kaldalu, N.; Tenson, T. The Frequency of Persisters in Escherichia coli Reflects the Kinetics of Awakening from Dormancy. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3379–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goormaghtigh, F.; Melderen, L. Van Single-Cell Imaging and Characterization of Escherichia coli Persister Cells to Ofloxacin in Exponential Cultures. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetani, M.; Fujisawa, M.; Okura, R.; Nozoe, T.; Suenaga, S.; Nakaoka, H.; Kussell, E.; Wakamoto, Y. Observation of Persister Cell Histories Reveals Diverse Modes of Survival in Antibiotic Persistence. Elife 2025, 14, e79517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LRenbarger, T.; M Baker, J.; Matthew Sattley, W. Slow and Steady Wins the Race: An Examination of Bacterial Persistence. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaldalu, N.; Hauryliuk, V.; Tenson, T. Persisters—As Elusive as Ever. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6545–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.K.; Knabel, S.J.; Kwan, B.W. Bacterial Persister Cell Formation and Dormancy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7116–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.E.; Van den Bergh, B.; Verstraeten, N.; Michiels, J. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications of Bacterial Persistence. Drug Resist. Updates 2016, 29, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semanjski, M.; Gratani, F.L.; Englert, T.; Nashier, P.; Beke, V.; Nalpas, N.; Germain, E.; George, S.; Wolz, C.; Gerdes, K.; et al. Proteome Dynamics during Antibiotic Persistence and Resuscitation. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmaerts, D.; Govers, S.K.; Michiels, J. Assessing Persister Awakening Dynamics Following Antibiotic Treatment in E. coli. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmaerts, D.; Focant, C.; Matthay, P.; Michiels, J. Transcription-Coupled DNA Repair Underlies Variation in Persister Awakening and the Emergence of Resistance. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Allison, K.R. Resuscitation Dynamics Reveal Persister Partitioning after Antibiotic Treatment. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2023, 19, MSB202211320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Tian, T.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Yao, G.; et al. ATP-Dependent Dynamic Protein Aggregation Regulates Bacterial Dormancy Depth Critical for Antibiotic Tolerance. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 143–156.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yamasaki, R.; Song, S.; Zhang, W.; Wood, T.K. Single Cell Observations Show Persister Cells Wake Based on Ribosome Content. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. ‘Viable but non-culturable Cells’ Are Dead. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 2335–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.; Dewachter, L.; Michiels, J. Protein Aggregation as a Bacterial Strategy to Survive Antibiotic Treatment. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 669664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.; Louwagie, S.; Deroover, F.; Duverger, W.; Khodaparast, L.; Khodaparast, L.; Hofkens, D.; Schymkowitz, J.; Rousseau, F.; Dewachter, L.; et al. Composition and Liquid-to-Solid Maturation of Protein Aggregates Contribute to Bacterial Dormancy Development and Recovery. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chowdhury, N.; Yamasaki, R.; Wood, T.K. Viable but Non-culturable and Persistence Describe the Same Bacterial Stress State. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. Waiting for Godot: Response to ‘How Dead Is Dead? Viable but Non-culturable versus Persister Cells. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 246–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. Mostly Dead and All Dead: Response to ‘what Do We Mean by Viability in Terms of “Viable but Non-culturable Cells”. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, R.; Song, S.; Benedik, M.J.; Wood, T.K. Persister Cells Resuscitate Using Membrane Sensors That Activate Chemotaxis, Lower CAMP Levels, and Revive Ribosomes. iScience 2020, 23, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windels, E.M.; Ben Meriem, Z.; Zahir, T.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Hersen, P.; Van den Bergh, B.; Michiels, J. Enrichment of Persisters Enabled by a SS-Lactam-Induced Filamentation Method Reveals Their Stochastic Single-Cell Awakening. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notley-McRobb, L.; Death, A.; Ferenci, T. The Relationship between External Glucose Concentration and CAMP Levels inside Escherichia coli: Implications for Models of Phosphotransferase-Mediated Regulation of Adenylate Cyclase. Microbiology 1997, 143, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Stapleton, M.R.; Smith, L.J.; Artymiuk, P.J.; Kahramanoglou, C.; Hunt, D.M.; Buxton, R.S. Cyclic-AMP and Bacterial Cyclic-AMP Receptor Proteins Revisited: Adaptation for Different Ecological Niches. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, J.S.; Hazelbauer, G.L.; Falke, J.J. Signaling and Sensory Adaptation in Escherichia coli Chemoreceptors: 2015 Update. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowsell, E.H.; Smith, J.M.; Wolfe, A.; Taylor, B.L. CheA, CheW, and CheY Are Required for Chemotaxis to Oxygen and Sugars of the Phosphotransferase System in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 6011–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, J.; Groisman, E.A. Reduced ATP-Dependent Proteolysis of Functional Proteins during Nutrient Limitation Speeds the Return of Microbes to a Growth State. Sci. Signal 2021, 14, eabc4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, M.H.; Yeom, J.; Groisman, E.A. Reducing Ribosome Biosynthesis Promotes Translation during Low Mg 2 + Stress. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, H.; Chang, Z. Regrowth-Delay Body as a Bacterial Subcellular Structure Marking Multidrug-Tolerant Persisters. Cell Discov. 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Malinovska, L.; Saha, S.; Wang, J.; Alberti, S.; Krishnan, Y.; Hyman, A.A. ATP as a Biological Hydrotrope. Science 2017, 356, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.G.; Mohiuddin, S.G.; Ananda, A.; Orman, M. Unraveling CRP/CAMP-Mediated Metabolic Regulation in Escherichia coli Persister Cells. Elife 2025, 13, RP99735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. PpGpp Ribosome Dimerization Model for Bacterial Persister Formation and Resuscitation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prossliner, T.; Skovbo Winther, K.; Sørensen, M.A.; Gerdes, K. Ribosome Hibernation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, K.; Wada, A.; Wada, C. Expression of Ribosome Modulation Factor (RMF) in Escherichia coli Requires PpGpp. Genes Cells 2001, 6, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Ishihama, A. Involvement of Cyclic AMP Receptor Protein in Regulation of the Rmf Gene Encoding the Ribosome Modulation Factor in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueta, M.; Yoshida, H.; Wada, C.; Baba, T.; Mori, H.; Wada, A. Ribosome Binding Proteins YhbH and YfiA Have Opposite Functions during 100S Formation in the Stationary Phase of Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 2005, 10, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, A.; Igarashi, K.; Yoshimura, S.; Aimoto, S.; Ishihama, A. Ribosome Modulation Factor: Stationary Growth Phase-Specific Inhibitor of Ribosome Functions from Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 214, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.; Rogers, J.; Kearns, M.; Leslie, M.; Hartson, S.D.; Wilson, K.S. Escherichia coli Persister Cells Suppress Translation by Selectively Disassembling and Degrading Their Ribosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 95, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zborníková, E.; Rejman, D.; Gerdes, K. Novel (p)PpGpp Binding and Metabolizing Proteins of Escherichia coli. mBio 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, R.M.; Bellows, L.E.; Wood, A.; Gründling, A. PpGpp Negatively Impacts Ribosome Assembly Affecting Growth and Antimicrobial Tolerance in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1710–E1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Hao, C.; Lam, H. Specific Enrichment and Proteomics Analysis of Escherichia coli Persisters from Rifampin Pretreatment. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 3984–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Lam, H. Proteomic Investigation of Tolerant Escherichia coli Populations from Cyclic Antibiotic Treatment. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynska, D.; Matuszewska, E.; Kuczynska-Wisnik, D.; Furmanek-Blaszk, B.; Laskowska, E. The Formation of Persister Cells in Stationary-Phase Cultures of Escherichia coli Is Associated with the Aggregation of Endogenous Proteins. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowska, E.; Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K. Role of Protein Aggregates in Bacteria. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2025, 145, 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewachter, L.; Bollen, C.; Wilmaerts, D.; Louwagie, E.; Herpels, P.; Matthay, P.; Khodaparast, L.; Khodaparast, L.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; et al. The Dynamic Transition of Persistence toward the Viable but Nonculturable State during Stationary Phase Is Driven by Protein Aggregation. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Laskowska, E. Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Protective Protein Aggregates in Bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, A.; Wang, R.; Sandoval, E.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, R. Solid-to-Liquid Phase Transition in the Dissolution of Cytosolic Misfolded-Protein Aggregates. iScience 2023, 26, 108334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougan, D.A.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Protein Folding and Degradation in Bacteria: To Degrade or Not to Degrade? That Is the Question. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, R.; Moradi, S.; Zarrine-Afsar, A.; Glover, J.R.; Kay, L.E. Unraveling the Mechanism of Protein Disaggregation Through a ClpB-DnaK Interaction. Science 2013, 339, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyffer, F.; Kummer, E.; Oguchi, Y.; Winkler, J.; Kumar, M.; Zahn, R.; Sourjik, V.; Bukau, B.; Mogk, A. Hsp70 Proteins Bind Hsp100 Regulatory M Domains to Activate AAA + Disaggregase at Aggregate Surfaces. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, A.M.; Brynildsen, M.P. Ploidy Is an Important Determinant of Fluoroquinolone Persister Survival. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 2039–2050.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.C. Mechanisms of Action of Antimicrobials: Focus on Fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völzing, K.G.; Brynildsen, M.P. Stationary-Phase Persisters to Ofloxacin Sustain DNA Damage and Require Repair Systems Only during Recovery. mBio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslowska, K.H.; Makiela-Dzbenska, K.; Fijalkowska, I.J. The SOS System: A Complex and Tightly Regulated Response to DNA Damage. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2019, 60, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Wang-Kan, X.; Neuberger, A.; van Veen, H.W.; Pos, K.M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Luisi, B.F. Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Structure, Function and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 523–539, Erratum in Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmiller, T.; Andersson, A.M.C.; Tomasek, K.; Balleza, E.; Kiviet, D.J.; Hauschild, R.; Tkačik, G.; Guet, C.C. Biased Partitioning of the Multidrug Efflux Pump AcrAB-TolC Underlies Long-Lived Phenotypic Heterogeneity. Science 2017, 356, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delmar, J.A.; Su, C.-C.; Yu, E.W. Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2014, 43, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, B.A.; Zenick, B.; Rocha-Granados, M.C.; Englander, H.E.; Hare, P.J.; LaGree, T.J.; DeMarco, A.M.; Mok, W.W.K. The AcrAB-TolC Efflux Pump Impacts Persistence and Resistance Development in Stationary-Phase Escherichia coli Following Delafloxacin Treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneau, S.; Michaux, C.; Giorgio, R.T.; Helaine, S. Intoxication of Antibiotic Persisters by Host RNS Inactivates Their Efflux Machinery during Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Meouche, I.; Dunlop, M.J. Heterogeneity in Efflux Pump Expression Predisposes Antibiotic-Resistant Cells to Mutation. Science 2018, 362, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zou, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Ke, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Baker, M.A.B.; et al. Enhanced Efflux Activity Facilitates Drug Tolerance in Dormant Bacterial Cells. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostalu, J.; Jõers, A.; Luidalepp, H.; Kaldalu, N.; Tenson, T. Cell Division in Escherichia Colicultures Monitored at Single Cell Resolution. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.; Zhang, Z.; Khodursky, A.; Kaldalu, N.; Kurg, K.; Lewis, K. Persisters: A Distinct Physiological State of E. coli. BMC Microbiol. 2006, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, K.J.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Mechanism of Quinolone Action and Resistance. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörr, T.; Vulić, M.; Lewis, K. Ciprofloxacin Causes Persister Formation by Inducing the TisB Toxin in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, A.; Lewis, K.; Vulić, M. Tolerance of Escherichia coli to Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics Depends on Specific Components of the SOS Response Pathway. Genetics 2013, 195, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, T.; Lewis, K.; Vulić, M. SOS Response Induces Persistence to Fluoroquinolones in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Herzfeld, A.M.; Leon, G.; Brynildsen, M.P. Differential Impacts of DNA Repair Machinery on Fluoroquinolone Persisters with Different Chromosome Abundances. mBio 2024, 15, e00374-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, W.W.K.; Brynildsen, M.P. Timing of DNA Damage Responses Impacts Persistence to Fluoroquinolones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6301–E6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, C.P.; Sancar, A. Molecular Mechanism of Transcription-Repair Coupling. Science 1993, 260, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobta, A.; Sarmini, L. Transcription-Coupled Nucleotide Excision Repair: A Faster Solution or the Only Option? Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epshtein, V.; Kamarthapu, V.; McGary, K.; Svetlov, V.; Ueberheide, B.; Proshkin, S.; Mironov, A.; Nudler, E. UvrD Facilitates DNA Repair by Pulling RNA Polymerase Backwards. Nature 2014, 505, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebali, O.; Chiou, Y.-Y.; Hu, J.; Sancar, A.; Selby, C.P. Genome-Wide Transcription-Coupled Repair in Escherichia Coli Is Mediated by the Mfd Translocase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2116–E2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Marr, M.T.; Roberts, J.W.E. Coli Transcription Repair Coupling Factor (Mfd Protein) Rescues Arrested Complexes by Promoting Forward Translocation. Cell 2002, 109, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portman, J.R.; Brouwer, G.M.; Bollins, J.; Savery, N.J.; Strick, T.R. Cotranscriptional R-Loop Formation by Mfd Involves Topological Partitioning of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019630118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, L.U.; Farewell, A.; Nyström, T. PpGpp: A Global Regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spira, B.; Ospino, K. Diversity in E. coli (p)PpGpp Levels and Its Consequences. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patacq, C.; Chaudet, N.; Létisse, F. Crucial Role of PpGpp in the Resilience of Escherichia coli to Growth Disruption. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarthapu, V.; Epshtein, V.; Benjamin, B.; Proshkin, S.; Mironov, A.; Cashel, M.; Nudler, E. PpGpp Couples Transcription to DNA Repair in E. coli. Science 2016, 352, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Minnick, P.J.; Pribis, J.P.; Garcia-Villada, L.; Hastings, P.J.; Herman, C.; Rosenberg, S.M. PpGpp and RNA-Polymerase Backtracking Guide Antibiotic-Induced Mutable Gambler Cells. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 1298–1310.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapragasam, S. The Emerging Role of (p)PpGpp in DNA Repair and Associated Bacterial Survival against Fluoroquinolones. Gene Expr. 2024, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonika, S.; Singh, S.; Mishra, S.; Verma, S. Toxin-Antitoxin Systems in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14220, Erratum in Heliyon 2025, 11, e42945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.; Christensen, S.K.; Gerdes, K. Rapid Induction and Reversal of a Bacteriostatic Condition by Controlled Expression of Toxins and Antitoxins. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.K.; Mikkelsen, M.; Pedersen, K.; Gerdes, K. RelE, a Global Inhibitor of Translation, Is Activated during Nutritional Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14328–14333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Yadav, M.; Ghosh, C.; Rathore, J.S. Bacterial Toxin-Antitoxin Modules: Classification, Functions, and Association with Persistence. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J. Physiological Heterogeneity in Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yao, S. Persisters of Bacterial Biofilms. In Exploring Bacterial Biofilms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, A.; Maisonneuve, E.; Gerdes, K. Mechanisms of Bacterial Persistence during Stress and Antibiotic Exposure. Science 2016, 354, aaf4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathy, J.P.; Zuccotto, F.; Hsinpin, H.; Sandberg, L.; Via, L.E.; Marriner, G.A.; Masquelin, T.; Wyatt, P.; Ray, P.; Dartois, V. Prediction of Drug Penetration in Tuberculosis Lesions. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gengenbacher, M.; Kaufmann, S.H.E. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Success through Dormancy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.-R.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Liao, K.; Shi, Q.-S.; Huang, X.-B.; Xie, X.-B. Efflux Pumps of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Their Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying Multidrug Resistance. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2025, 202, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Alexandre, K.; Etienne, M. Tolerance and Persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Biofilms Exposed to Antibiotics: Molecular Mechanisms, Antibiotic Strategies and Therapeutic Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Buchad, H.; Gajjar, D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Persister Cell Formation upon Antibiotic Exposure in Planktonic and Biofilm State. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, R.A.; von Eiff, C.; Kahl, B.C.; Becker, K.; McNamara, P.; Herrmann, M.; Peters, G. Small Colony Variants: A Pathogenic Form of Bacteria That Facilitates Persistent and Recurrent Infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.E.; Wagner, N.J.; Li, L.; Beam, J.E.; Wilkinson, A.D.; Radlinski, L.C.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, E.A.; Conlon, B.P. Reactive Oxygen Species Induce Antibiotic Tolerance during Systemic Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 5, 282–290, Erratum in Nat Microbiol. 2020, 5, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamaga, B.; Kong, L.; Pasquina-Lemonche, L.; Lafage, L.; von und zur Muhlen, M.; Gibson, J.F.; Grybchuk, D.; Tooke, A.K.; Panchal, V.; Culp, E.J.; et al. Demonstration of the Role of Cell Wall Homeostasis in Staphylococcus Aureus Growth and the Action of Bactericidal Antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2106022118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeaux, D.; Chauhan, A.; Rendueles, O.; Beloin, C. From in Vitro to in Vivo Models of Bacterial Biofilm-Related Infections. Pathogens 2013, 2, 288–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkeren, E.; Diard, M.; Hardt, W.-D. Evolutionary Causes and Consequences of Bacterial Antibiotic Persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Surviving cells/ survivors | Cells that remain viable after antibiotic exposure, without necessarily fulfilling the definition of persister cells; may follow healthy, damaged, failed, or VBNC trajectories. |

| Persister cells | A subpopulation of survivors that tolerate antibiotics without genetic resistance, enter a lag phase, successfully resume growth, and produce viable progeny. |

| Failed persister cells | Survivors that initiate recovery (e.g., elongation or filamentation) but fail to complete the first division and do not form colonies. |

| VBNC (viable but non-culturable) cells | Cells that retain membrane integrity and minimal metabolic activity but are unable to resume growth; many are structurally compromised “cell shells” and effectively non-recoverable. |

| Awakening | The transition of persister cells from dormancy to the first successful division, involving metabolic reactivation, detoxification, repair, and restoration of proteostasis. |

| Lag phase (awakening lag) | The time period between the transfer of persister cells into antibiotic-free nutrient-rich conditions and the completion of the first division. |

| Category | Factor | Effect on Lag Time/ Awakening (Evidence Level) * | General Role | Ref ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic (pre-existing before antibiotic exposure) | ATP level | Low ATP → long lag; ATP rise required for growth (S2) | ATP fuels repair, disaggregation, translation restart | [25,46,54] |

| Ribosome abundance | High → fast; low → delayed (S2) | Pre-existing ribosomes enable immediate translation; low pool requires de novo synthesis | [47,65] | |

| Protein aggregates (load & solubility) | Liquid/small → fast; solid/large → long lag/VBNC (S2) | Aggregates must be dissolved to release essential proteins | [50,62] | |

| Chaperone capacity (DnaK-ClpB) | Strong → efficient awakening; weak → failure (S1) | ATP-dependent disaggregation and refolding of aggregated proteins | [46,50,62] | |

| Nutrient-sensing systems (PTS, chemotaxis) | Efficient sensing → fast exit from dormancy (S2) | Detect nutrients, lower cAMP, activate growth programs | [54] | |

| Dormancy depth | Shallow → short lag; deep → long lag/VBNC (S2) | Defines how much reactivation and repair is required | [34] | |

| (p)ppGpp level/ stringent response | High (p)ppGpp → deeper dormancy; indirect extension of lag (C1) | Sets dormancy depth via global translational repression | [112] | |

| Toxin–antitoxin–mediated growth arrest (e.g., MazEF, RelBE) | TA-induced persisters → prolonged lag (C1) | Reversible inhibition of translation and/or replication; | [103] | |

| Chromosome copy number (ploidy) | ≥2 chromosomes → higher survival, faster recovery (S1) | Extra template improves DNA damage repair | [84] | |

| Damage-related (acquired during antibiotic exposure) | Residual intracellular antibiotic | High concentration → long lag (S2) | Drug must be cleared before growth resumes | [45] |

| Efflux activity (AcrAB–TolC) | High → short lag; low → prolonged lag (S1) | Pumps out antibiotics, enables metabolic restart | [45] | |

| Cell-wall damage (β-lactams) | Structural defects slow recovery (S2) | Wall rebuilt after detox; damage partitioned during division | [45] | |

| DNA double-strand breaks (fluoroquinolones) | More breaks → longer lag; severe → failure (S1) | Must be repaired before replication and division | [36] | |

| Homologous recombination (HR) RecA/RecBCD | Efficient HR → successful recovery (S1) | Repairs DSBs using intact DNA template | [84] | |

| Transcription-coupled repair (TCR) UvrD vs. Mfd | UvrD → shorter lag; Mfd → longer lag + mutagenesis (S1) | Repairs transcription-blocking lesions | [44] | |

| Filamentation and damage partitioning | Extends lag; supports survival of one lineage (S2) | Dilutes damage; asymmetric divisions | [45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Laskowska, E.; Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D. Molecular Basis of Persister Awakening and Lag-Phase Recovery in Escherichia coli After Antibiotic Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010467

Stojowska-Swędrzyńska K, Laskowska E, Kuczyńska-Wiśnik D. Molecular Basis of Persister Awakening and Lag-Phase Recovery in Escherichia coli After Antibiotic Exposure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010467

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojowska-Swędrzyńska, Karolina, Ewa Laskowska, and Dorota Kuczyńska-Wiśnik. 2026. "Molecular Basis of Persister Awakening and Lag-Phase Recovery in Escherichia coli After Antibiotic Exposure" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010467

APA StyleStojowska-Swędrzyńska, K., Laskowska, E., & Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D. (2026). Molecular Basis of Persister Awakening and Lag-Phase Recovery in Escherichia coli After Antibiotic Exposure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010467