Incretin Mimetics as Potential Therapeutics for Concussion and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

TBI and Incretin Mimetics

2. Results—Incretin Mimetic Use in Concussion, TBI, and Neuroinflammation

3. Discussion

3.1. TBI Pathophysiology

Neuroinflammation

3.2. Common Outcomes of Incretin Use in TBI and Neuroinflammation

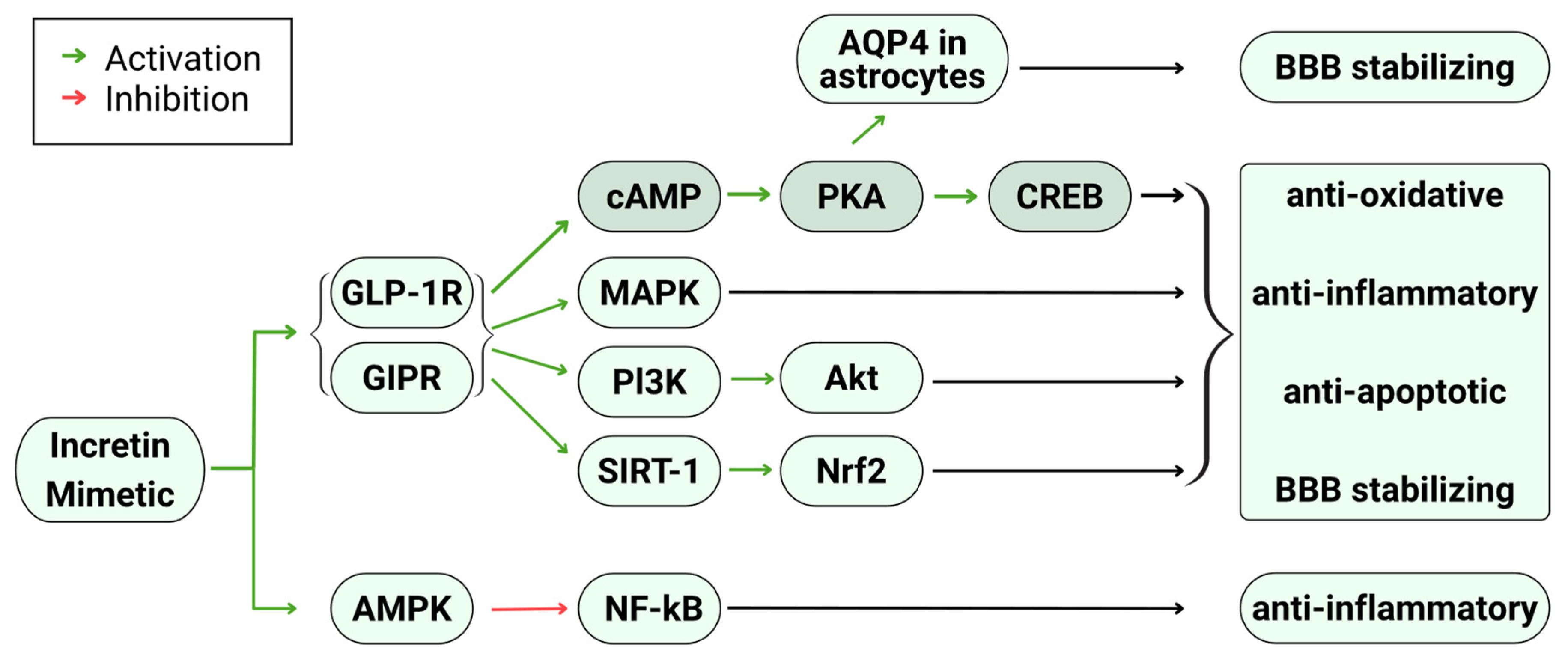

3.3. Mechanisms Underlying Neuroprotective and Neurotrophic Properties of Incretin Mimetics

4. Methodology

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1RAs | glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists |

| GIP | glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide |

| Gcg | glucagon |

| T2DM | type 2 Diabetes mellitus |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| Iba1 | ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 |

| GFAP | glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| CREB | cAMP response element binding protein |

| PKA | protein kinase A |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| SERT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| AQP4 | aquaporin 4 |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

References

- Killen, M.J.; Giorgi-Coll, S.; Helmy, A.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Carpenter, K.L. Metabolism and inflammation: Implications for traumatic brain injury therapeutics. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Creed, J.A.; Raghupathi, R. Frontiers in Neuroengineering Pathophysiology of Mild TBI: Implications for Altered Signaling Pathways. In Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects; Kobeissy, F.H., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg, J.; Smith, T. Traumatic Brain Injury. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Harej Hrkać, A.; Pilipović, K.; Belančić, A.; Juretić, L.; Vitezić, D.; Mršić-Pelčić, J. The Therapeutic Potential of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists in Traumatic Brain Injury. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, K.; Borsi, L.; Sterling, A.; Giacino, J.T. Recovery after moderate to severe TBI and factors influencing functional outcome: What you need to know. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2024, 97, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.K. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rellan, M.J.; Drucker, D.J. New Molecules and Indications for GLP-1 Medicines. JAMA 2025, 334, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. Could GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Like Semaglutide Treat Addiction, Alzheimer Disease, and Other Conditions? JAMA 2024, 331, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Sharma, S. Recent Advances in Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotfelty, E.J.; Delgado, T.; Tovar, Y.R.L.B.; Luo, Y.; Hoffer, B.; Olson, L.; Karlsson, T.; Mattson, M.P.; Harvey, B.; Tweedie, D.; et al. Incretin Mimetics as Rational Candidates for the Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 2, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Wen, Z.; Lu, Z.; Cui, L.; Fu, C.; Xue, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Beyond Their Pancreatic Effects. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 721135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhajib, M.; Tayab, Z.; Di Marco, C.; Suh, D.D. The pharmacokinetics and comparative bioavailabilty of oral and subcutaneous semaglutide in healthy volunteers. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 36, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkáč, I.; Gotthardová, I. Pharmacogenetic aspects of the treatment of Type 2 diabetes with the incretin effect enhancers. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, A.; Wu, C.C.; Lawley, S.D. Alternative dosing regimens of GLP-1 receptor agonists may reduce costs and maintain weight loss efficacy. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 2251–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulton, D.W. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Saxagliptin, a Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, T.S.; Rhea, E.M.; Talbot, K.; Banks, W.A. Brain uptake pharmacokinetics of incretin receptor agonists showing promise as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease therapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, M.; Li, Y.; Lecca, D.; Rubovitch, V.; Tweedie, D.; Glotfelty, E.; Rachmany, L.; Kim, H.K.; Choi, H.I.; Hoffer, B.J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of PT302, a sustained-release Exenatide formulation, in a murine model of mild traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, E.M.; Babin, A.; Thomas, P.; Omer, M.; Weaver, R.; Hansen, K.; Banks, W.A.; Talbot, K. Brain uptake pharmacokinetics of albiglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide, and DA5-CH in the search for new treatments of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Tissue Barriers 2024, 12, 2292461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Malik, R.; Singh, G.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Mohan, S.; Albratty, M.; Albarrati, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Pathogenesis and management of traumatic brain injury (TBI): Role of neuroinflammation and anti-inflammatory drugs. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Shen, Z.; Anraku, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Chen, X. Nanomaterial-based blood-brain-barrier (BBB) crossing strategies. Biomaterials 2019, 224, 119491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, S.; Blouet, C. Brain access of incretins and incretin receptor agonists to their central targets relevant for appetite suppression and weight loss. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E472–E480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulhameed, N.; Babin, A.; Hansen, K.; Weaver, R.; Banks, W.A.; Talbot, K.; Rhea, E.M. Comparing regional brain uptake of incretin receptor agonists after intranasal delivery in CD-1 mice and the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bader, M.; Tamargo, I.; Rubovitch, V.; Tweedie, D.; Pick, C.G.; Greig, N.H. Liraglutide is neurotrophic and neuroprotective in neuronal cultures and mitigates mild traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, M.; Li, Y.; Tweedie, D.; Shlobin, N.A.; Bernstein, A.; Rubovitch, V.; Tovar, Y.R.L.B.; DiMarchi, R.D.; Hoffer, B.J.; Greig, N.H.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects and Treatment Potential of Incretin Mimetics in a Murine Model of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmany, L.; Tweedie, D.; Li, Y.; Rubovitch, V.; Holloway, H.W.; Miller, J.; Hoffer, B.J.; Greig, N.H.; Pick, C.G. Exendin-4 induced glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation reverses behavioral impairments of mild traumatic brain injury in mice. Age 2013, 35, 1621–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedie, D.; Rachmany, L.; Rubovitch, V.; Lehrmann, E.; Zhang, Y.; Becker, K.G.; Perez, E.; Miller, J.; Hoffer, B.J.; Greig, N.H.; et al. Exendin-4, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist prevents mTBI-induced changes in hippocampus gene expression and memory deficits in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 239, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, I.A.; Bader, M.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Talbot, K.; DiMarchi, R.D.; Pick, C.G.; Greig, N.H. Novel GLP-1R/GIPR co-agonist “twincretin” is neuroprotective in cell and rodent models of mild traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 288, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.W.; Hsieh, T.H.; Chen, K.Y.; Wu, J.C.; Hoffer, B.J.; Greig, N.H.; Li, Y.; Lai, J.H.; Chang, C.F.; Lin, J.W.; et al. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Ameliorates Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Cognitive and Sensorimotor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in Rats. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 2044–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakon, J.; Ruscher, K.; Romner, B.; Tomasevic, G. Preservation of the blood brain barrier and cortical neuronal tissue by liraglutide, a long acting glucagon-like-1 analogue, after experimental traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakin, K.; Li, Y.; Chiang, Y.H.; Hoffer, B.J.; Rosenheim, H.; Greig, N.H.; Miller, J.P. Exendin-4 ameliorates traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive impairment in rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, A.; Xu, C.; Hou, J.; Hong, J. GLP-1(7-36) protected against oxidative damage and neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampal CA region after traumatic brain injury by regulating ERK5/CREB. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Han, S.; Sha, Z.; Liu, M.; Dong, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Lu, S.; Xu, Z.; et al. Cerebral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation alleviates traumatic brain injury by glymphatic system regulation in mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 3876–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DellaValle, B.; Hempel, C.; Johansen, F.F.; Kurtzhals, J.A. GLP-1 improves neuropathology after murine cold lesion brain trauma. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2014, 1, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, Y.L.; Linnane, C.; Mao, Y.; Anwer, A.G.; Sapkota, A.; Annissa, T.F.; Herok, G.; Vissel, B.; Oliver, B.G.; et al. L-Carnitine and extendin-4 improve outcomes following moderate brain contusion injury. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedie, D.; Rachmany, L.; Rubovitch, V.; Li, Y.; Holloway, H.W.; Lehrmann, E.; Zhang, Y.; Becker, K.G.; Perez, E.; Hoffer, B.J.; et al. Blast traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive deficits are attenuated by preinjury or postinjury treatment with the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, exendin-4. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Welch, P.; Sanders, S.; Gan, R.Z. Mitigation of Hearing Damage After Repeated Blast Exposures in Animal Model of Chinchilla. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2022, 23, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Sanders, S.; Gan, R.Z. Mitigation of Hearing Damage with Liraglutide Treatment in Chinchillas After Repeated Blast Exposures at Mild-TBI. Mil. Med. 2023, 188, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmany, L.; Tweedie, D.; Rubovitch, V.; Li, Y.; Holloway, H.W.; Kim, D.S.; Ratliff, W.A.; Saykally, J.N.; Citron, B.A.; Hoffer, B.J.; et al. Exendin-4 attenuates blast traumatic brain injury induced cognitive impairments, losses of synaptophysin and in vitro TBI-induced hippocampal cellular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Zhang, C.; He, J.; Wang, Y. Semaglutide alleviates early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage by suppressing ferroptosis and neuroinflammation via SIRT1 pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.K.; Chen, Q.; Chen, S.; Huang, B.; Ren, B.G.; Shi, S.S. GLP-1R Agonist Liraglutide Attenuates Inflammatory Reaction and Neuronal Apoptosis and Reduces Early Brain Injury After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Inflammation 2021, 44, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Enkhjargal, B.; Wu, L.; Zhou, K.; Sun, C.; Hu, X.; Gospodarev, V.; Tang, J.; You, C.; Zhang, J.H. Exendin-4 attenuates neuronal death via GLP-1R/PI3K/Akt pathway in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Neuropharmacology 2018, 128, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Manaenko, A.; Hakon, J.; Hansen-Schwartz, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. Liraglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 mimetic, and its metabolite attenuate inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2012, 32, 2201–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giza, C.C.; Hovda, D.A. The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion. Neurosurgery 2014, 75, S24–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, A.; Theus, M.H. Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Ariza-Salamanca, D.F.; Corrales-Hernández, M.G.; Pachón-Londoño, M.J.; Hernandez-Duarte, I.; Calderon-Ospina, C.A. Revisiting Excitotoxicity in Traumatic Brain Injury: From Bench to Bedside. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, K.; Khan, H.; Singh, T.G.; Kaur, A. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanistic Insight on Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 71, 1725–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karve, I.P.; Taylor, J.M.; Crack, P.J. The contribution of astrocytes and microglia to traumatic brain injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSabato, D.J.; Quan, N.; Godbout, J.P. Neuroinflammation: The devil is in the details. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postolache, T.T.; Wadhawan, A.; Can, A.; Lowry, C.A.; Woodbury, M.; Makkar, H.; Hoisington, A.J.; Scott, A.J.; Potocki, E.; Benros, M.E.; et al. Inflammation in Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 74, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, B.L.; Gardner, R.C.; Godbout, J.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Keene, C.D. Traumatic Brain Injury and Risk of Neurodegenerative Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.K.; Rich, W.; Reilly, M.A. Oxidative stress in the brain and retina after traumatic injury. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1021152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.G.; Yong, Y.Y.; Pan, Y.R.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wei, J.; Yu, L.; Law, B.Y.; et al. Targeting Nrf2-Mediated Oxidative Stress Response in Traumatic Brain Injury: Therapeutic Perspectives of Phytochemicals. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 1015791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Shi, W.; Ye, Y.; Xu, K.; Hu, J.; Chao, H.; Tao, Z.; Xu, L.; Gu, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Atox1 protects hippocampal neurons after traumatic brain injury via DJ-1 mediated anti-oxidative stress and mitophagy. Redox Biol. 2024, 72, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, X.M.; Wu, L.Y.; Liu, G.J.; Xu, W.D.; Zhang, X.S.; Gao, Y.Y.; Tao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Aucubin alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation via Nrf2-mediated signaling activity in experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoo, M.; O’Halloran, P.J.; Henry, J.; Ben Husien, M.; Brennan, P.; Campbell, M.; Caird, J.; Curley, G.F. Permeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier after Traumatic Brain Injury: Radiological Considerations. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, J. Incretins: Clinical perspectives, relevance, and applications for the primary care physician in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, S38–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgano, M.; Toshkezi, G.; Qiu, X.; Russell, T.; Chin, L.; Zhao, L.R. Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Treatment Strategies and Future Endeavors. Cell Transplant. 2017, 26, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Cejudo, J.; Wisniewski, T.; Marmar, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; de Leon, M.J.; Fossati, S. Traumatic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Cerebrovascular Link. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, K.O.; Glotfelty, E.J.; Li, Y.; Greig, N.H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and neuroinflammation: Implications for neurodegenerative disease treatment. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 186, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölscher, C. Glucagon-like peptide-1 class drugs show clear protective effects in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: A revolution in the making? Neuropharmacology 2024, 253, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Maclagan, K.; Skene, S.S.; Bajwa-Joseph, M.; Letchford, D.; Chowdhury, K.; Hibbert, S.; Budnik, N.; Zampedri, L.; Dickson, J.; et al. Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Rosanbalm, S.; Leinonen, M.; Olanow, C.W.; To, D.; Bell, A.; Lee, D.; Chang, J.; Dubow, J.; Dhall, R.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Incretin Mimetic | Model | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Protocols and Results | |||

| Liraglutide. Commenced 30 min after injury and continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment | Li et al. [23] |

| Liraglutide. Pre-treated 1 h before injury. | Human SH-SY5Y and SH-hGLP-1R#9 neuroblastoma cells and rat primary neuronal cultures | Induced cellular proliferation, recovered loss in cell viability due to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, decreased caspase-3 activity, did not decrease apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) levels | Li et al. [23] |

| Liraglutide or Twincretin. Commenced 30 min after injury and continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment, neuronal degeneration, and microglial activation but not astrogliosis, recovered mTBI induced p-PKA reduction | Bader et al. [24] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced immediately after trauma or pre-treated for 2 days. Continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment, no significant improvement in passive avoidance | Rachmany et al. [25] |

| Exendin-4. Pre-treated shortly before injury or rapid treatment post insult. | Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and rat primary neuronal cultures | Recovered loss in cell viability due to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress | Rachmany et al. [25] |

| Exendin-4. Pretreated for 2 days and continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased visual memory impairment, recovered altered gene expression | Tweedie et al. [26] |

| Twincretin. Commenced 30 min after injury and continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment | Tamargo et al. [27] |

| Twincretin. Pre-treated 1 h before injury. | Human SH-SY5Y and SH-hGLP-1R#9 neuroblastoma cells and rat primary neuronal cultures | Increased cAMP levels and induced CREB pathway activation, recovered loss in cell viability due to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress | Tamargo et al. [27] |

| PT302. Commenced 1 h after injury and continued for 7 days. | Mild TBI murine model (rats and mice) | Decreased visual and spatial memory impairment, neuronal degeneration, and microglial activation but not astrogliosis | Bader et al. [17] |

| GIP. Pre-treated 2 days before injury. Continued for 14 days. | Mild TBI murine model (rats) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment, balance and fine motor impairment, astrogliosis, apoptosis, and axonal damage, did not affect sensorimotor impairment | Yu et al. [28] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced 10 min after injury. Continued 12, 24, and 36 h after injury. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (rats) | Decreased sensorimotor impairment, cerebral edema, blood–brain barrier permeability, and cortical lesion size but not thalamic, did not reduce thalamic delayed neuronal cell death | Hakon et al. [29] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced 30 min after injury and continued for 7 days. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (rats) | Decreased spatial memory impairment | Eakin et al. [30] |

| Exendin-4. Pre-treated 1 h before injury or rapid treatment post insult. | Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and rat primary neuronal cultures | Recovered loss in cell viability due to excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, decreased caspase-3 activity | Eakin et al. [30] |

| GLP-1(7–36). Commenced immediately after injury and continued for 30 days. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (rats) | Decreased neurological deficits, sensorimotor impairment, spatial memory impairment, cerebral edema, caspase-3 activity, and levels of hydrogen peroxide and reactive oxygen species, increased antioxidant factors, induced activation of the ERK5/CREB signaling pathways | Wang et al. [31] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced 1 h after injury and continued for 30 days. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased spatial and visual memory impairment, blood–brain barrier dysfunction, astrogliosis, axonal injury, and caspase-3 activity, recovered glymphatic system dysfunction and aquaporin 4 polarization | Lv et al. [32] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced immediately after injury and continued for 3 days. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, inflammatory cytokines, lesion size, and apoptotic-induced caspase activity, did not affect astrogliosis, increased CREB activation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor | DellaValle et al. [33] |

| L-Carnitine and Exendin-4. Commenced immediately after injury. Continued for 14 days. | Moderate-severe TBI murine model (rats) | Decreased visual memory, sensorimotor and sensory function impairment, and oxidative stress, no decrease in microglial activation or astrogliosis, increased antioxidants, did not affect caspase-3 activity | Chen et al. [34] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced 2 h after injury or pre-treated for 2 days. Continued for 7 days. | Blast TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased neurodegeneration and visual memory impairment, recovered altered gene expression | Tweedie et al. [35] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced 2 h after injury or pre-treated for 2 days. Continued for 7 days. | Blast TBI chinchilla model | Increased hearing recovery, decreased caspase-3 activity | Jiang et al. [36] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced 2 h after injury or pre-treated for 2 days. Continued for 7 days. | Blast TBI chinchilla model | Increased hearing recovery | Jiang et al. [37] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced 2 h after injury or pre-treated for 2 days. Continued for 7 days. | Blast TBI murine model (mice) | Decreased visual and spatial memory impairment, recovered loss in synaptophysin immunoreactivity | Rachmany et al. [38] |

| Exendin-4. Pre-treated 2 h before injury | Mouse hippocampal HT22 cells | Recovered loss in cell viability and reduction in neurite length | Rachmany et al. [38] |

| Subarachnoid and Intracerebral Hemorrhage Models | |||

| Semaglutide. Commenced immediately after injury. Continued for 2 days. | Subarachnoid hemorrhage murine model (mice) | Decreased cerebral edema, neuronal cell death, ferroptosis, oxidative stress, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression | Chen et al. [39] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced 2 h after injury. Continued 12 h after injury. | Subarachnoid hemorrhage murine model (rats) | Decreased neurological function and sensorimotor deficit, cerebral edema, blood–brain barrier permeability, microglial activation, apoptosis, level of oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and caspase-3 activation | Tu et al. [40] |

| Exendin-4. Commenced 1 h after injury. | Subarachnoid hemorrhage murine model (rats) | Decreased neurological function, sensorimotor deficit, spatial memory deficit, and apoptosis | Xie et al. [41] |

| Liraglutide. Commenced 1 h after injury. Continued for 3 days. | Intracerebral hemorrhage murine model (mice) | Decreased cerebral edema, neurological function, sensorimotor deficit, and neutrophil infiltration and activation, increased cAMP levels | Hou et al. [42] |

| Outcome | Number of Articles | Model Type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo | In Vitro | ||

| Memory deficits | 14 | 14 | N/A |

| Excitotoxicity + oxidative stress | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Inflammation + blood–brain barrier dysfunction | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Sensorimotor impairment | 7 | 7 | N/A |

| Stimulation of anti-apoptotic and pro-survival pathways | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Key Search Terms | Incretin(s) | Total Number of Screened Papers | 112 |

| incretin mimetic(s) | |||

| glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; GIP | |||

| glucose-dependent insulin-releasing hormone | |||

| gastric inhibitory peptide | |||

| glucagon-like peptide-1; GLP-1 | |||

| glucagon receptor agonist(s) | |||

| glucagon | |||

| semaglutide | |||

| exenatide | |||

| liraglutide | |||

| exendin-4 | |||

| dulaglutide | |||

| albiglutide | |||

| lixisenatide | |||

| tirzepatide | |||

| ozempic | |||

| traumatic brain injury; TBI | |||

| concussion | |||

| neuroinflammation | |||

| Screening Inclusion Criteria | Incretins in concussions | Number of Papers Included | 21 |

| Incretins in traumatic brain injury (TBI) | |||

| Incretins in TBI sequelae | |||

| Incretins in neuroinflammation associated with TBI | |||

| Incretins in TBI associated hemorrhage | |||

| Articles published from 2012–2025 | |||

| Screening Exclusion Criteria | Incretins in models of stroke | Number of Papers Excluded | 91 |

| Incretins in models of ischemic brain injury | |||

| Non-traumatic induction of injury in model | |||

| Spinal cord injuries | |||

| Non-incretin intervention | |||

| Non-TBI associated neuroinflammation | |||

| Articles published before 2012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sipos, S.; Jerkic, M.; Rotstein, O.D.; Schweizer, T.A. Incretin Mimetics as Potential Therapeutics for Concussion and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010045

Sipos S, Jerkic M, Rotstein OD, Schweizer TA. Incretin Mimetics as Potential Therapeutics for Concussion and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleSipos, Samuel, Mirjana Jerkic, Ori D. Rotstein, and Tom A. Schweizer. 2026. "Incretin Mimetics as Potential Therapeutics for Concussion and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010045

APA StyleSipos, S., Jerkic, M., Rotstein, O. D., & Schweizer, T. A. (2026). Incretin Mimetics as Potential Therapeutics for Concussion and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010045