Efficacy and Tolerability of Bupropion in Major Depressive Disorder with Comorbid Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias

2.5. Synthesis and Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

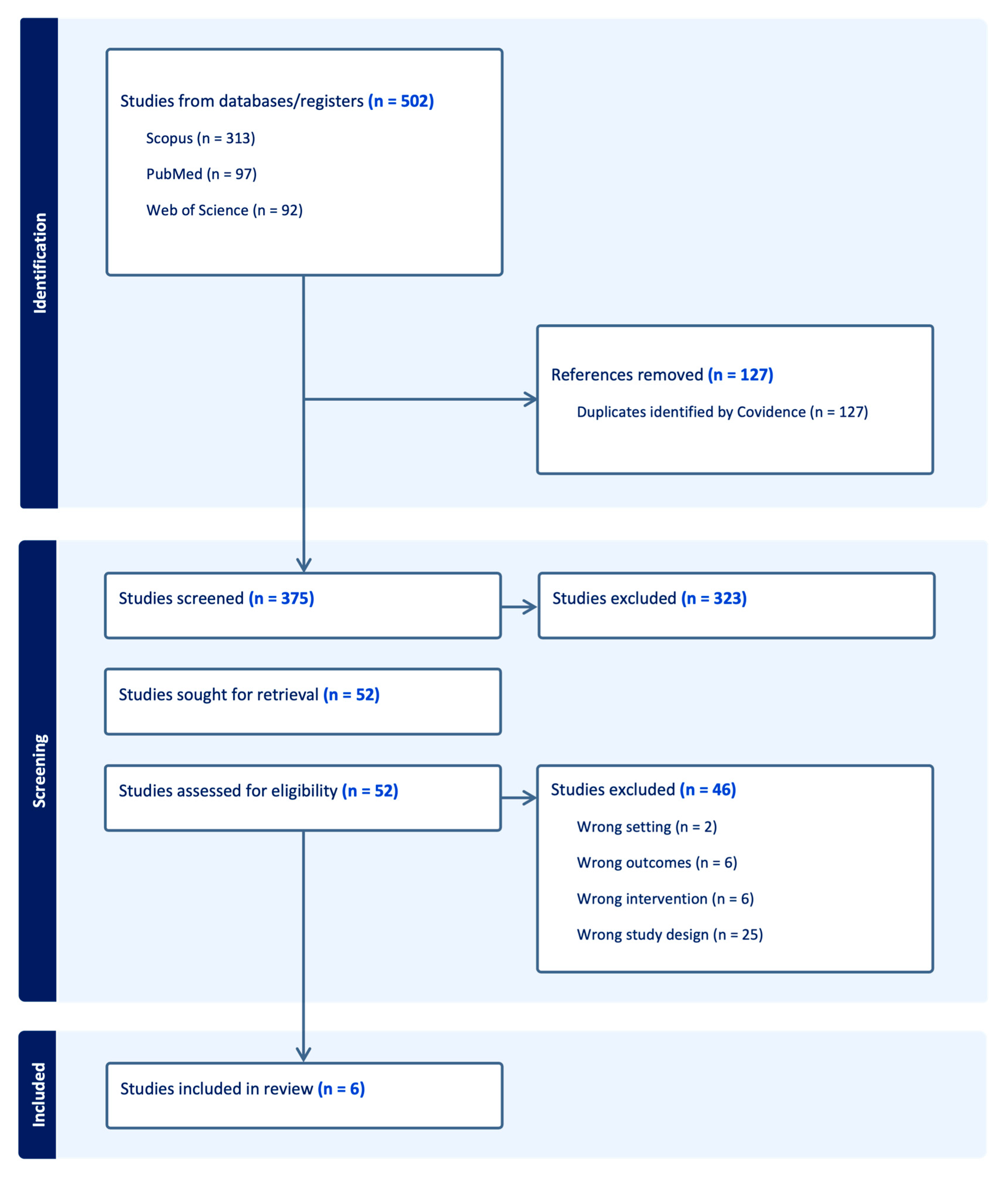

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Randomized Controlled Trials

3.2.1. Pooled Analyses

3.2.2. Individual Randomized Trials

3.3. Open-Label Trials

3.4. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy

4.2. Safety and Tolerability

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence Base

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fava, M.; Alpert, J.E.; Carmin, C.N.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Trivedi, M.H.; Biggs, M.M.; Shores-Wilson, K.; Morgan, D.; Schwartz, T.; Balasubramani, G.K.; et al. Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, M. Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Commentary on Prevalence and Clinical Implications. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12 (Suppl. S1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, D.F.; Niciu, M.J.; Henter, I.D.; Zarate, C.A. Defining Anxious Depression: A Review of the Literature. CNS Spectr. 2013, 18, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etkin, A.; Wager, T.D. Functional Neuroimaging of Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Processing in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.P.; Etkin, A.; Furman, D.J.; Lemus, M.G.; Johnson, R.F.; Gotlib, I.H. Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis and new integration of base line activation and neural response data. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, B.; Gelenberg, A.; Wang, P.; Merriam, A.; McIntyre, J.S.; Charles, S.C.; Zarin, D.A.; Altshuler, K.Z.; Tasman, A.; Cook, I.A.; et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). American Psychiatric Association. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157 (Suppl. S4), 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Garakani, A.; Murrough, J.W.; Freire, R.C.; Thom, R.P.; Larkin, K.; Buono, F.D.; Iosifescu, D.V. Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 595584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosmann, N.P.; Costa, M.d.A.; Jaeger, M.d.B.; Motta, L.S.; Frozi, J.; Spanemberg, L.; Manfro, G.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Pine, D.S.; Salum, G.A. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and stress disorders: A 3-level network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, B.T.; Greer, T.L.; Trivedi, M.H. Strategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants: Targeting residual symptoms. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampf, C.; Scherf-Clavel, M.; Weiß, C.; Klüpfel, C.; Stonawski, S.; Hommers, L.; Lichter, K.; Erhardt-Lehmann, A.; Unterecker, S.; Domschke, K.; et al. Effects of Anxious Depression on Antidepressant Treatment Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opbroek, A.; Delgado, P.L.; Laukes, C.; McGahuey, C.; Katsanis, J.; Moreno, F.A.; Manber, R. Emotional blunting associated with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Do SSRIs inhibit emotional responses? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 5, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serretti, A.; Chiesa, A. Sexual side effects of pharmacological treatment of psychiatric diseases. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakostas, G.I.; Stahl, S.M.; Krishen, A.; Seifert, C.A.; Tucker, V.L.; Goodale, E.P.; Fava, M. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): A pooled analysis of 10 studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, C.T.; Johnson, L.G. Bupropion Normalizes Cognitive Performance in Patients With Depression. Medscape Gen. Med. 2007, 9, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken, A.J.; Dichter, G.S.; Freid, C.; Addington, S.; Shelton, R.C. Assessing the effects of bupropion SR on mood dimensions of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Allen, S.; Haque, M.N.; Angelescu, I.; Baumeister, D.; Tracy, D.K. Bupropion: A systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness as an antidepressant. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connarn, J.N.; Zhang, X.; Babiskin, A.; Sun, D. Metabolism of Bupropion by Carbonyl Reductases in Liver and Intestine. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eum, S.; Sayre, F.; Lee, A.M.; Stingl, J.C.; Bishop, J.R. Association of CYP2B6 genetic polymorphisms with bupropion and hydroxybupropion exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2022, 42, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, W. Emotional Roles of Mono-Aminergic Neurotransmitters in Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliacoff, Z.; Belanger, H.G.; Winsberg, M. Does Bupropion Increase Anxiety? A Naturalistic Study Over 12 Weeks. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 43, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Carmody, T.J.; Donahue, R.M.; Bolden-Watson, C.; Houser, T.L.; Metz, A. Do bupropion SR and sertraline differ in their effects on anxiety in depressed patients? J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parris, M.S.; Marver, J.E.; Chaudhury, S.R.; Ellis, S.P.; Metts, A.V.; Keilp, J.G.; Burke, A.K.; Oquendo, M.A.; Mann, J.J.; Grunebaum, M.F. Effects of anxiety on suicidal ideation: Exploratory analysis of a paroxetine versus bupropion randomized trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 33, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, C.; Terranova, F.; Loiacono, P.; Caudullo, V.; Russo, R.G.; Luca, M.; Cafiso, M. Bupropion in the treatment of major depressive disorder: A comparison with paroxetine. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Psychopathol. 2010, 16, 128–133. Available online: https://old.jpsychopathol.it/article/bupropion-in-the-treatment-of-major-depressive-disorder-a-comparison-with-paroxetine/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rush, A.J.; Carmody, T.J.; Haight, B.R.; Rockett, C.B.; Zisook, S. Does Pretreatment Insomnia or Anxiety Predict Acute Response to Bupropion SR? Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005, 17, 1–9. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/10401230590905263 (accessed on 14 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.S.; Vornik, L.A.; Khan, D.A.; Rush, A.J. Bupropion in the treatment of outpatients with asthma and major depressive disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2007, 37, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldak, S.E.; Maristany, A.J. Bupropion and Anxiety: A Brief Review. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 40, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Design | Intervention/Comparator | Anxiety Outcomes | Other Main Findings | Exploratory Anxiety Outcome (Scale, Week, ΔMean, p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trivedi et al., 2001 [23] | Pooled analysis of 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs; n = 692 outpatients with recurrent DSM-IV MDD; duration: 8 weeks | Bupropion SR (n = 234), Sertraline (n = 225), Placebo (n = 233) | Both bupropion and sertraline reduced HAM-A significantly vs. placebo, with no difference between the two active drugs. Anxiolytic effects emerged early (week 1) and became clinically significant by week 4. | Both antidepressants outperformed placebo on depressive symptoms. Tolerability was good overall; somnolence was more common with sertraline. | HAM-A, week 8: ΔMean = +0.5 (ns) |

| Papakostas et al., 2008 [14] | Patient-level pooled analysis of 10 multicenter RCTs; n = 2122 adults with DSM-IV MDD, 1275 with anxious depression (HAM-D A/S ≥ 7); duration: 6–12 weeks | Bupropion SR/XL (up to 300–400 mg/day) vs. SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline) | Among anxious depression patients, SSRIs achieved higher response (65.4% vs. 59.4%, p = 0.03) and greater HAM-A reduction (−10.3 vs. −9.0, p < 0.05). No differences in the non-anxious subgroup. | SSRIs caused more sexual dysfunction; insomnia was more frequent with bupropion. | HAM-A, final: ΔMean = −0.9 (p < 0.05) |

| Parris/Grunebaum et al., 2018 [24] | Double-blind RCT; n = 74 adults with DSM-IV MDD and current/past suicidality; duration: 8 weeks | Paroxetine CR 25–50 mg/day (n = 36) vs. Bupropion XL 150–450 mg/day (n = 38) | Post hoc analysis: baseline anxiety moderated suicidal ideation outcomes, with a trend for greater SSI reduction with paroxetine at higher anxiety levels. | Both treatments reduced suicidal ideation over time. | N/A (post hoc; no anxiety mean reported) |

| Calandra et al., 2010 [25] | Randomized open-label trial; n = 30 Italian outpatients with DSM-IV-TR MDD; duration: 24 weeks | Bupropion XL 150 mg/day (n = 15) vs. Paroxetine 20 mg/day (n = 15) | HAM-A decreased substantially in both groups (−54.3% vs. −61.6%), with no significant between-group difference. | Both groups showed comparable reductions in HAM-D and MADRS. Sexual side effects diverged: bupropion improved ASEX scores, while paroxetine worsened them (p < 0.01), especially in men. | HAM-A, week 24: ΔMean = −0.8 (ns) |

| Rush et al., 2005 [26] | Multicenter open-label study; n = 797 outpatients with DSM-IV recurrent, nonpsychotic MDD across 21 US sites; duration: 8 weeks | Bupropion SR: 150 mg/day for 3 days, then 300 mg/day (mean ~295 mg/day) | HAM-A decreased markedly (from 16.3 to 7.4). Pretreatment anxiety delayed antidepressant response by ~1 week but did not reduce final likelihood of anxiolysis. | Depressive symptoms improved strongly (HAM-D decreased from 22.3 to 8.9); response 66.9%, remission 55.5%. | N/A (Single-arm open-label design, no control group) |

| Brown et al., 2007 [27] | Open-label pilot study; n = 18 outpatients with DSM-IV MDD and comorbid asthma (14 evaluable); duration: 12 weeks | Bupropion: 150 mg/day for 1 week, then 300 mg/day | HAM-A decreased modestly (−2.1, p = 0.04). | HAM-D decreased by 4.7 points (p = 0.02). Improvements in depression correlated with better asthma control (r = 0.73, p = 0.001). | N/A (Single-arm open-label design, no control group) |

| Outcome | Studies (Included Evidence Base) | Certainty of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms (HAM-A/HDRS-24 anxiety clusters) | 2 Pooled RCT [14,23], 2 RCT [24,25], 2 open-label [26,27] | Low |

| Depressive symptoms (HAM-D/MADRS) | 2 Pooled RCT [14,23], 1 RCT [25], 2 open-label [26,27]. | Moderate |

| Response (≥50% reduction in depression scale) | 2 Pooled RCT [14,23], 1 RCT [25], 2 open-label [26,27]. | Moderate |

| Remission (scale threshold) | 1 Pooled RCT [14], 2 open-label [26,27]. | Low |

| Tolerability—Sexual dysfunction | 1 RCT [25] | Low |

| Tolerability—Insomnia | 1 open-label [26] | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinzi, M.; Cuomo, A.; Koukouna, D.; Gualtieri, G.; Pierini, C.; Rescalli, M.B.; Pardossi, S.; Patrizio, B.; Fagiolini, A. Efficacy and Tolerability of Bupropion in Major Depressive Disorder with Comorbid Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411767

Pinzi M, Cuomo A, Koukouna D, Gualtieri G, Pierini C, Rescalli MB, Pardossi S, Patrizio B, Fagiolini A. Efficacy and Tolerability of Bupropion in Major Depressive Disorder with Comorbid Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411767

Chicago/Turabian StylePinzi, Mario, Alessandro Cuomo, Despoina Koukouna, Giacomo Gualtieri, Caterina Pierini, Maria Beatrice Rescalli, Simone Pardossi, Benjamin Patrizio, and Andrea Fagiolini. 2025. "Efficacy and Tolerability of Bupropion in Major Depressive Disorder with Comorbid Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411767

APA StylePinzi, M., Cuomo, A., Koukouna, D., Gualtieri, G., Pierini, C., Rescalli, M. B., Pardossi, S., Patrizio, B., & Fagiolini, A. (2025). Efficacy and Tolerability of Bupropion in Major Depressive Disorder with Comorbid Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411767