Vascular Complications of Long COVID—From Endothelial Dysfunction to Systemic Thrombosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

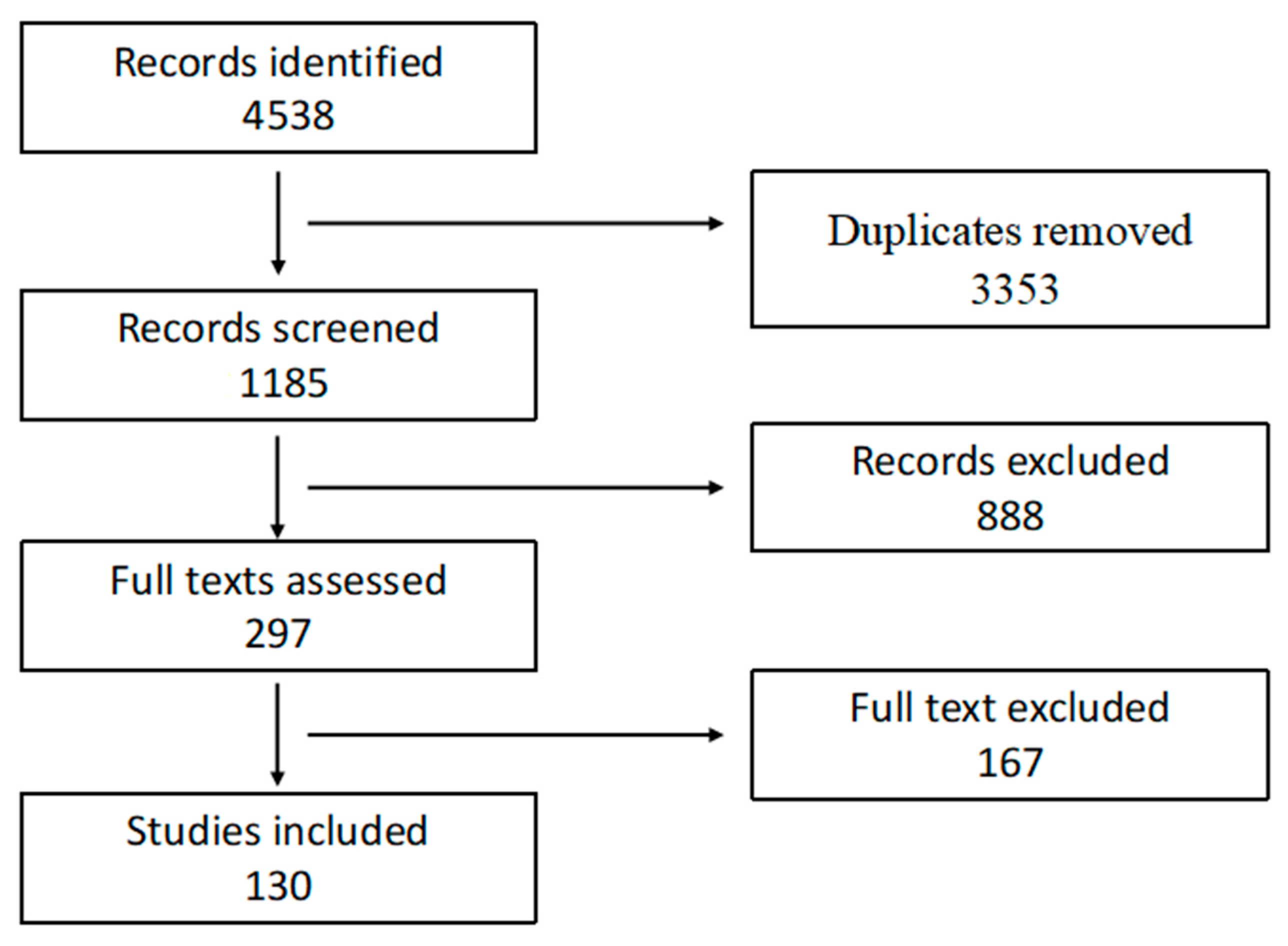

2. Methods

2.1. Review Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- ○

- Indicators of endothelial dysfunction (e.g., vascular reactivity, endothelial biomarkers);

- ○

- Evidence of coagulopathy (e.g., D-dimer, fibrinogen, hypercoagulability assays);

- ○

- Markers of immunothrombosis (e.g., neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), platelet activation markers);

- ○

- Clinical thromboembolic events (e.g., deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE)).

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

- Endothelial injury and vascular dysfunction;

- Coagulation and fibrinolytic dysregulation;

- Immunothrombosis and platelet activation;

- Clinical thromboembolic events: incidence and risk factors.

3. Pathophysiology of Vascular Complications in Long COVID

3.1. Long COVID and Endothelial Dysfunction

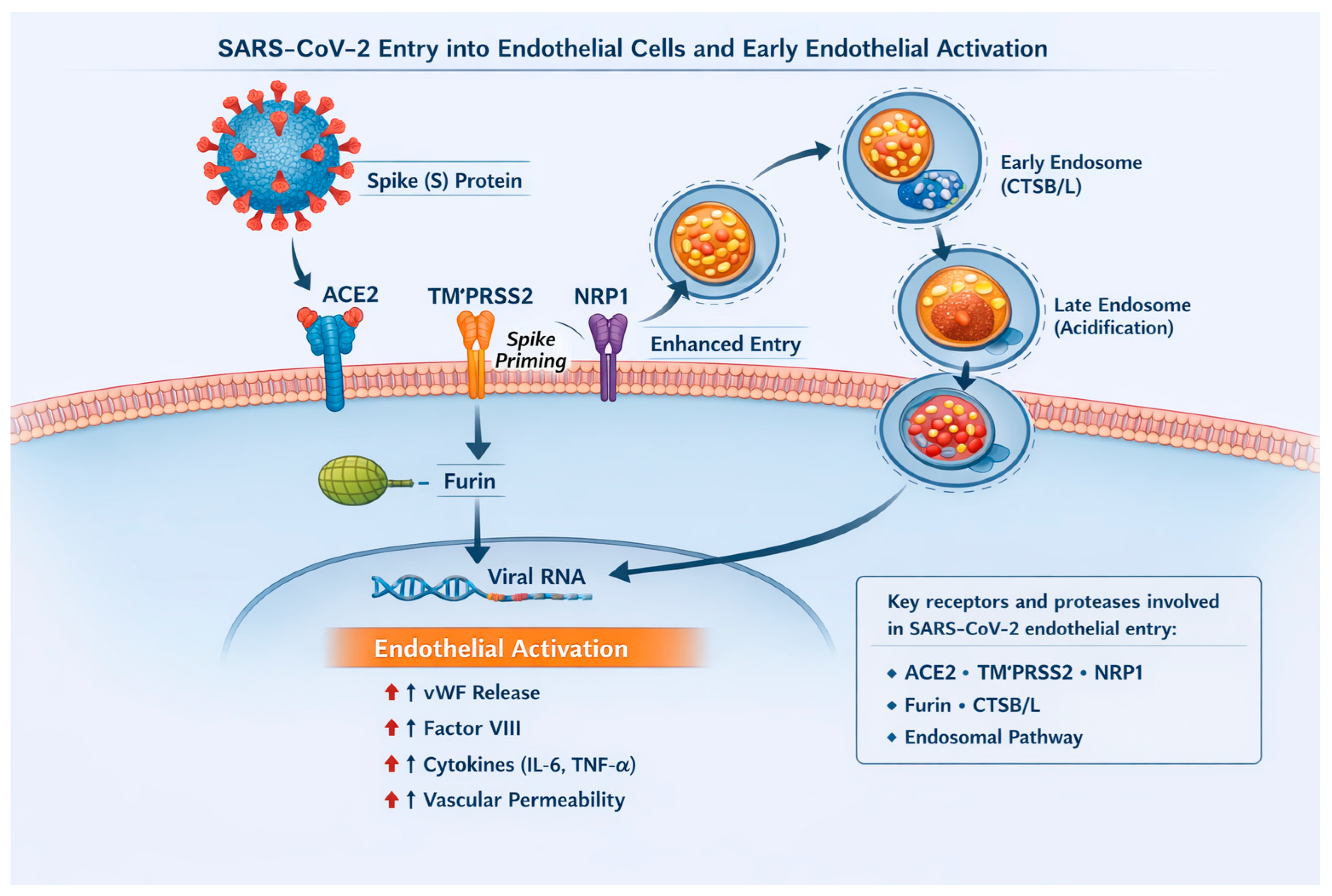

3.1.1. Endothelial Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2

3.1.2. Endothelial Dysfunction in Long COVID

3.1.3. Microinflammation and Endothelial Activation

3.1.4. Glycocalyx Damage

3.1.5. Microthrombosis and Impaired Microcirculation

3.2. COVID-19 and Coagulation

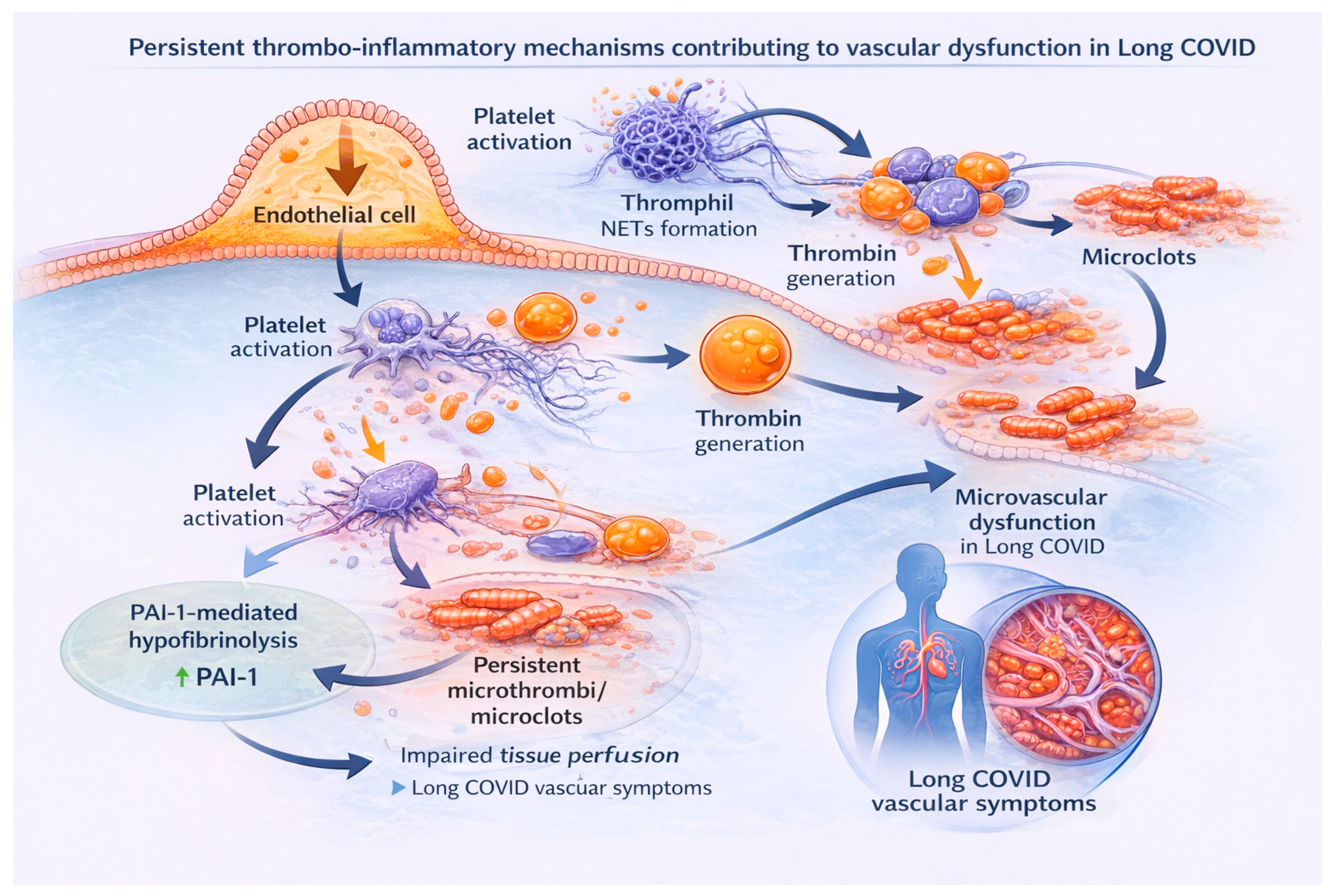

3.2.1. Immunothrombosis

3.2.2. The Coagulation System in COVID-19

3.3. Persistent Vascular Disturbances and Coagulopathy in Long COVID

4. Complications of Long COVID

4.1. Venous Thromboembolic Complications

4.2. Arterial Thromboembolic Complications

4.2.1. Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and Acute Myocardial Infarction

4.2.2. Ischaemic Stroke

4.2.3. Cardiac Arrhythmias

4.2.4. Myocarditis

4.2.5. Heart Failure

4.3. Microvascular and Peripheral Manifestations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| Long COVID | LC |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NASEM | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

| PASC | Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 |

| NETs | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| DVT | Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| PE | Pulmonary Embolism |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| TMPRSS2 | Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| FMD | Flow-Mediated Vasodilatation |

| O2− | Superoxide Radicals |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| vWF | von Willebrand Factor |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 |

| tPA | tissue Plasminogen Activator |

| uPA | urokinase Plasminogen Activator |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| MPO-DNA | Myeloperoxidase-DNA |

| FDP | Fibrin Degradation Products |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| PT | Prothrombin Time |

| aPTT | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time |

| aPL | Antiphospholipid Antibodies |

| aCL | Anticardiolipin |

| anti-β2GPI | anti-β2-Glycoprotein I |

| LA | Lupus Anticoagulant |

| VTE | Venous Thromboembolism |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events |

| cfPWV | Carotid–Femoral Pulse Wave Velocity |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| LGE | Late Gadolinium Enhancement |

| NVC | Nailfold Videoocapillaroscopy |

| ANA | Antinuclear Antibodies |

References

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Epidemiological Update—24 December 2024; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update---24-december-2024 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Wu, X.; Xiang, M.; Liu, L.; Novakovic, V.A.; Shi, J. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Thrombosis in Acute and Long COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 992384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146, Correction in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID): Case Definition and Key Messages; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-covid-19-condition-(long-covid) (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Barbar, S.; Noventa, F.; Rossetto, V.; Ferrari, A.; Brandolin, B.; Perlati, M.; De Bon, E.; Tormene, D.; Pagnan, A.; Prandoni, P. A Risk Assessment Model for the Identification of Hospitalized Medical Patients at risk for Venous Thromboembolism: The Padua Prediction Score. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 2450–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and Predictors of Long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631, Correction in Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Kim, S.S.; Lindsell, C.J.; Billig Rose, E.; Shapiro, N.I.; Files, D.C.; Gibbs, K.W.; Erickson, H.L.; Steingrub, J.S.; Smithline, H.A.; et al. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, H.; Townsend, L.; Ni Cheallaigh, C.; Bergin, C.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Browne, P.; Carty, C.; O’Connor, L.; O’Dwyer, C.; Ryan, P.; et al. Persistent endotheliopathy in the pathogenesis of long COVID syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Pavli, A.; Tsakris, A. Post-COVID syndrome: An insight on its pathogenesis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Davis, H.; McCorkell, L.; Soares, L.; Wulf-Hanson, S.; Iwasaki, A.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2148–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroni, M.G.; Piantoni, S.; Masneri, S.; Garrafa, E.; Martini, G.; Tincani, A.; Andreoli, L.; Franceschini, F. Coagulation Dysfunction in COVID-19: The Interplay Between Inflammation, Viral Infection and the Coagulation System. Blood Rev. 2021, 46, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Thachil, J.; Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. Coagulation Abnormalities and Thrombosis in Patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e438–e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J. Long COVID: A Clinical Update. Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Long COVID or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC) and the Urgent Need to Identify Diagnostic Biomarkers and Risk Factors. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e946512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, A.G.; Vrettou, C.S.; Keskinidou, C.; Dimopoulou, I.; Kotanidou, A.; Orfanos, S.E. Endotheliopathy in Acute COVID-19 and Long COVID. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H.; Adachi, H.; Hakoshima, M.; Katsuyama, H.; Sako, A. The Significance of Endothelial Dysfunction in Long COVID-19 for the Possible Future Pandemic of Chronic Kidney Disease and Cardiovascular Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial Cell Infection and Endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, A.M.; Diz, D.I.; Chappell, M.C. COVID-19, ACE2, and the Cardiovascular Consequences. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1084–H1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhou, L.; Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, D.W.; Wei, J. Deep Insight Into Cytokine Storm: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Huang, Q.; Wan, L.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, B.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Advances in Research on the Release of von Willebrand Factor from Endothelial Cells through the Membrane Attack Complex C5b-9 in Sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 6719–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, G.; Volpe, M.; Savoia, C. Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension: Current Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 798958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric Oxide Synthases: Regulation and Function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.C.; Rainger, G.E.; Mason, J.C.; Guzik, T.J.; Osto, E.; Stamataki, Z.; Neil, D.; Hoefer, I.E.; Fragiadaki, M.; Waltenberger, J.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in COVID-19: A Position Paper of the ESC Working Group for Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, and the ESC Council of Basic Cardiovascular Science. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, G.; D’Elia, S.; Morello, M.; Titolo, G.; Luisi, E.; Solimene, A.; Serpico, C.; Conte, S.; Natale, F.; Loffredo, F.S.; et al. Cardio-Pulmonary Features of Long COVID: From Molecular and Histopathological Characteristics to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, K.; Postma, R.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; Harms, A.; Hankemeier, T. Microvessels-on-chip: Exploring Endothelial Cells and COVID-19 Plasma Interaction with Nitric Oxide Metabolites. Nitri. Oxide 2025, 155, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia Luciani, G.; Visigalli, R.; Dall’Asta, V.; Rotoli, B.M.; Barilli, A. Cytokines from Macrophages Activated by Spike S1 of SARS-CoV-2 Cause eNOS/Arginase Imbalance in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, A.M.; Lighezan, D.F.; Nicoras, V.A.; Dumitrescu, P.; Bodea, O.M.; Velimirovici, D.E.; Otiman, G.; Banciu, C.; Nisulescu, D.D. Effects of COVID-19 Infection on Endothelial Vascular Function. Viruses 2025, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binesh, A.; Venkatachalam, K. IL 6 Cascade in Post COVID Cardiovascular Complications: A Review of Endothelial Injury and Clotting Pathways. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Drug Targets, 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, A.; Bursy, M.; Szkudlarek, W.; Linkiewicz, J.; Fabiszewski, Z.; Starosta, P. Chronic Cardiovascular Disorders Associated with COVID-19: A Literature Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e93271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ochoa, A.J.; Szolnoky, G.; Hernandez-Ibarra, A.G.; Fareed, J. Treatment with Sulodexide Downregulates Biomarkers for Endothelial Dysfunction in Convalescent COVID-19 Patients. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2025, 31, 10760296241297647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielle, R.C.S.; Débora, D.M.; Alessandra, N.L.P.; Alexia, S.S.Z.; Débora, M.C.R.; Elizabel, N.V.; Felipe, A.M.; Giulia, M.G.; Henrique, P.R.; Karen, R.M.B.; et al. Correlating COVID-19 Severity with Biomarker Profiles and Patient Prognosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, A.; Joffe, D.; Lloyd-Jones, G.; Khan, M.A.; Šalamon, Š.; Laubscher, G.J.; Putrino, D.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. Vascular Pathogenesis in Acute and Long COVID: Current Insights and Therapeutic Outlook. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2025, 51, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U.; Aja, P.M.; Okoroiwu, G.I.A.; Ubosi, N.I.; Pius, T.; Ashiru, M.; Akaba, K.; Adias, T.C. Soluble Platelet Selectin and Platelets in COVID-19: A Multifaceted Connection. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 4634–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, D.; Sorrentino, S.; Ferretti, A.; Morello, R.; Valentini, P.; Di Gennaro, L.; De Candia, E. Circulating Activated Platelets in Children with Long COVID: A Case-Controlled Preliminary Observation. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, e430–e433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesgards, J.F.; Cerdan, D.; Perronne, C. Do Long COVID and COVID Vaccine Side Effects Share Pathophysiological Picture and Biochemical Pathways? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7879, Correction in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, B.P.; da Silva, J.A.M.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Palmeira, J.D.F.; Amato, A.A.; Argañaraz, G.A.; Argañaraz, E.R. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Long COVID-Part 2: Understanding the Impact of Spike Protein and Cellular Receptor Interactions on the Pathophysiology of Long COVID Syndrome. Viruses 2025, 17, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsiaris, A.G.; Karakousis, K. Long COVID Mechanisms, Microvascular Effects, and Evaluation Based on Incidence. Life 2025, 15, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Fang, Y.; Ye, T.; Li, H.; Lan, P. Factors Influencing Glycocalyx Degradation: A Narrative Review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1490395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, C.S.; Morrow, G.B.; Mitchell, J.L.; Chowdary, P.; Mutch, N.J. Fibrinolytic Abnormalities in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukahori, S.; Kawazoe, Y.; Han, J.Y.; Kolliputi, N.; Lezama, K.; Kumar, R.; Mukae, H.; Lockey, R.F.; Vera, I.M.; Kim, K.; et al. Elevated Plasma Level of PAI-1 is Associated with Severe COVID-19 Outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.A.; He, X.Y.; Denorme, F.; Campbell, R.A.; Ng, D.; Salvatore, S.P.; Mostyka, M.; Baxter-Stoltzfus, A.; Borczuk, A.C.; Loda, M.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Contribute to Immunothrombosis in COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Blood 2020, 3, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; Illescas-Montes, R.; Puerta-Puerta, J.M.; Ruiz, C.; Melguizo-Rodríguez, L. SARS-CoV-2 infection: The Role of Cytokines in COVID-19 Disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 54, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Long, H.; Sun, J.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, K.; Tong, Y.; Wang, B.; Wu, Q.; et al. New Laboratory Evidence for the Association Between Endothelial Dysfunction and COVID-19 Disease Progression. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3112–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkel, S.J.; Benjamens, S.; Dijk, A.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Pol, R.A. Circulating Myeloperoxidase–DNA Complexes as a Marker for Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Their Association with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in the General Population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H.; Levi, M.; Jecko Thachil, J. Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2103–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Tang, N.; Gando, S.; Falanga, A.; Cattaneo, M.; Levi, M.; Clark, C.; Iba, T. ISTH Interim Guidance on Recognition and Management of Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ardes, D.; Boccatonda, A.; Cocco, G.; Stefano Fabiani, S.; Rossi, I.; Bucci, M.; Guagnano, M.T.; Schiavone, C.; Cipollone, F. Impaired Coagulation, Liver Dysfunction and COVID-19: Discovering an Intriguing Relationship. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, F.L.; Vogler, T.O.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Wohlauer, M.V.; Urban, S.; Nydam, T.L.; Moore, P.K.; McIntyre, R.C. Fibrinolysis Shutdown Correlation with Thromboembolic Events in Severe COVID-19 Infection. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020, 231, 193e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Wang, C.; Zhu, W.; Chen, W. Coagulation Disorders and Thrombosis in COVID-19 Patients and a Possible Mechanism Involving Endothelial Cells: A Review. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I. The Dynamic Role of Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (suPAR) in Monitoring Coagulation Dysfunction During COVID-19 Progression: A Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 87, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Abnormal Coagulation Parameters are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, M.; Coste, F.; Meyer, A.; Enache, I.; Talha, S.; Charloux, A.; Reboul, C.; Geny, B. Mechanisms of Pulmonary Vasculopathy in Acute and Long-Term COVID-19: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, G.; Nini, G.; Frenț, S.M.; Cotoraci, C. Hematologic and Immunologic Overlap Between COVID-19 and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, L.H.; Nagy, M.; ten Cate, H.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Groh, L.A.; Leentjens, J.; Janssen, N.A.F.; Netea, M.G.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Hannink, G.; et al. Sustained Inflammation, Coagulation Activation and Elevated Endothelin-1 Levels Without Macrovascular Dysfunction at 3 Months After COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2022, 209, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Pang, J.; Ji, P.; Zhong, Z.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J. Coagulation Dysfunction is Associated with Severity of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Plebani, M. Laboratory Abnormalities in Patients with COVID-2019 Infection. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 25, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, J.; Tacquard, C.; Severac, F.; Leonard-Lorant, I.; Ohana, M.; Delabranche, X.; Merdji, H.; Clere-Jehl, R.; Schenck, M.; Fagot Gandet, F.F.; et al. High Risk of Thrombosis in Patients with Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Course and Risk Factors for Mortality of Adult in Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062, Correction in Lancet 2020, 395, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.M.; Barouqa, M.; Krause, G.J.; Gonzalez-Lugo, J.D.; Rahman, S.; Gil, M.R. Low ADAMTS13 Activity Correlates with Increased Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. TH Open 2021, 5, e89–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.E.; Fogarty, H.; Karampini, E.; Lavin, M.; Schneppenheim, S.; Dittmer, R.; Morrin, H.; Glavey, S.; Cheallaigh, C.N.; Bergin, C.; et al. ADAMTS13 Regulation of VWF Multimer Distribution in Severe COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzallah, I.; Debliquis, A.; Drénou, B. Lupus Anticoagulant is Frequent in Patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2064–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Parsa-Kondelaji, M.; Bos, M.H.A.; Mansouritorghabeh, H. Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2025, 58, 982–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertin, D.; Brodovitch, A.; Lopez, A.; Arcani, R.; Thomas, G.M.; Beziane, A.; Weber, S.; Babacci, B.; Heim, X.; Rey, L.; et al. Anti-Cardiolipin IgG Autoantibodies Associate with Circulating Extracellular DNA in Severe COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollerbach, A.; Müller-Calleja, N.; Pedrosa, D.; Canisius, A.; Sprinzl, M.F.; Falter, T.; Rossmann, H.; Bodenstein, M.; Werner, C.; Sagoschen, I.; et al. Pathogenic Lipid-Binding Antiphospholipid Antibodies are Associated with Severity of COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 19, 2335–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caillon, A.; Trimaille, A.; Favre, J.; Jesel, L.; Olivier Morel, O.; Kauffenstein, G. Role of Neutrophils, Platelets, and Extracellular Vesicles and Their Interactions in COVID-19-Associated Thrombopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimury, A.; Khameneh, M.T.; Khaledi, E.M. Major Coagulation Disorders and Parameters in COVID-19 Patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichmann, D.; Sperhake, J.P.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Steurer, S.; Edler, C.; Heinemann, A.; Heinrich, F.; Mushumba, H.; Kniep, I.; Schröder, A.S.; et al. Autopsy Findings and Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Vlok, M.; Venter, C.; Bezuidenhout, J.A.; Laubscher, G.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muys, M.; Demulder, A.; Besse-Hammer, T.; Ghorra, N.; Rozen, L. Exploring Hypercoagulability in Post-COVID Syndrome (PCS): An Attempt at Unraveling the Endothelial Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykara, Y.; Sevgy, K.; Akgun, Y. COVID-19 Microangiopathy: Insights into Plasma Exchange as a Therapeutic Strategy. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2025, 47, 103963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silingardi, M.; Zappulo, F.; Dormi, A.; Pizzini, A.M.; Donadei, C.; Cappuccilli, M.; Fantoni, C.; Zaccaroni, S.; Pizzuti, V.; Cilloni, N.; et al. Is COVID-19 Coagulopathy a Thrombotic Microangiopathy? A Prospective, Observational Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyatos, P.; Luque, N.; Sabater, G.; Eizaguirre, S.; Bonnin, M.; Orriols, R.; Tura-Ceide, O. Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Risk in Post-COVID-19 Patients After 6- and 12-Months SARS-CoV-2. Infection 2024, 52, 1269–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljadah, M.; Khan, N.; Beyer, A.M.; Chen, Y.; Blanker, A.; Widlansky, M.E. Clinical Implications of COVID-19-Related Endothelial Dysfunction. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, B.; Noris, M.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Kemper, C. The State of Complement in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Khan, A.; Putrino, D.; Woodcock, A.; Kell, D.K.; Pretorius, E. Long COVID: Pathophysiological Factors and Abnormalities of Coagulation. Trends Endocrino. Metab. 2023, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, W.; Tu, B.; Xiao, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Early Immunological and Inflammation Proteomic Changes in Elderly COVID-19 Patients Predict Severe Disease Progression. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iba, T.; Jerrold, H.; Levy, J.H.; Maier, C.L.; Connors, J.M.; Levi, M. Four Years Into the Pandemic, Managing COVID-19 Patients with Acute Coagulopathy: What have we Learned? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popazu, C.; Romila, A.; Petrea, M.; Grosu, R.M.; Lescai, A.M.; Vlad, A.L.; Oprea, V.D.; Baltă, A.A.S. Overview of Inflammatory and Coagulation Markers in Elderly Patients with COVID-19: Retrospective Analysis of Laboratory Results. Life 2025, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaloro, E.J.; Pasalic, L. Innovative Diagnostic Solutions in Hemostasis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, L.H.; Jacobs, L.M.C.; Groh, L.A.; ten Cate, H.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Wilson-Storey, B.; Hannink, G.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Ghossein-Doha, C.; Nagy, M.; et al. Vascular Function, Systemic Inflammation, and Coagulation Activation 18 Months after COVID-19 Infection: An Observational Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minno, A.; Ambrosino, P.; Calcaterra, I.; Di Minno, M.N.D. COVID-19 and Venous Thromboembolism: A Meta-analysis of Literature Studies. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.B.; Siqueira, S.; de Assis, S.W.R.; de Souza, R.F.; Santos, N.O.; Dos Santos, A.F.; da Silveira, P.R.; Tiwari, S.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Góes-Neto, A.; et al. Long-COVID and Post-COVID Health Complications: An Up-to-Date Review on Clinical Conditions and Their Possible Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses 2021, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, M.; Henes, J.; Saur, S. The Role of Antiphospholipid Antibodies in COVID-19. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Crawford, J.M.; Chen, Y.C.; Ashton, V.; Campbell, A.K.; Milentijevic, D.; Peacock, W.F. Occurrence of Thromboembolic Events and Mortality Among Hospitalized Coronavirus 2019 Patients: Large Observational Cohort Study of Electronic Health Records. TH Open 2022, 6, e408–e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, V.; Gianesello, L.; Horton, A. Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Thromboembolism: Cause of Disease or Epiphenomenon? J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 52, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.A.; Agrawal, D.K. Thromboembolism in the Complications of Long COVID-19. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 7, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rettew, A.; Garrahy, I.; Rahimian, S.; Brown, R.; Sangha, N. COVID-19 Coagulopathy. Life 2024, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patell, R.; Bogue, T.; Koshy, A.; Bindal, P.; Merrill, M.; Aird, W.C.; Bauer, K.A.; Zwicker, J.I. Postdischarge Thrombosis and Hemorrhage in Patients with COVID-19. Blood 2020, 136, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, A.M.; Li, D. Symptomatology of Long COVID Associated with Inherited and Acquired Thrombophilic Conditions: A Systematic Review. Viruses 2025, 17, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loutsidi, N.E.; Politou, M.; Vlahakos, V.; Korakakis, D.; Kassi, T.; Nika, A.; Pouliakis, A.; Eleftheriou, K.; Balis, E.; Pappas, A.G.; et al. Hypercoagulable Rotational Thromboelastometry During Hospital Stay Is Associated with Post-Discharge DLco Impairment in Patients with COVID-19-Related Pneumonia. Viruses 2024, 16, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płazak, W.; Drabik, L. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and SLE: Endothelial Dysfunction, Atherosclerosis, and Thrombosis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 42, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Giarratana, D.; Malatino, L. Evidence for the Interplay Between Inflammation and Clotting System in the Pathogenetic Chain of Pulmonary Embolism: A Potential Therapeutic Target to Prevent Multi-organ Failure and Residual Thrombotic Risk. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 23, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Engelen, M.M.; Barco, S.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Vanassche, T.; Hunt, B.J.; Vandenbriele, C.; Verhamme, P.; Kucher, N.; Rashidi, F.; et al. Incidence of Venous Thromboembolic Events in COVID-19 Patients After Hospital Discharge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thromb. Res. 2022, 209, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Barco, S.; Giannakoulas, G.; Engelen, M.M.; Hobohm, L.; Valerio, L.; Christophe Vandenbriele, C.; Peter Verhamme, P.; Vanassche, T.; Konstantinides, S.V. Risk of Venous Thromboembolic Events After COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2023, 55, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, C.A.; Sun, C.K.; Tsai, I.T.; Chang, Y.P.; Lin, M.C.; Hung, I.Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Wang, L.K.; Lin, Y.T.; Hung, K.C. Mortality and Risk Factors Associated with Pulmonary Embolism in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, M.; Lin, L.; Brandt, C.B.; Milusev, A.; Despont, A.; Shaw, J.; Döring, Y.; Luo, Y.; Rieben, R. Sustained Vascular Inflammatory Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein on Human Endothelial Cells. Inflammation 2025, 48, 2531–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Mei, Q.; Walline, J.H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Du, B. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1450470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, P.; Calcaterra, I.; Molino, A.; Moretta, P.; Lupoli, R.; Spedicato, G.A.; Papa, A.; Motta, A.; Maniscalco, M.; Di Minno, M.N.D. Persistent Endothelial Dysfunction in Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksova, A.; Fluca, A.L.; Gagno, G.; Pierri, A.; Padoan, L.; Derin, A.; Moretti, R.; Noveska, E.A.; Azzalini, E.; D’Errico, S.; et al. Long-term Effect of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Cardiovascular Outcomes and All-Cause Mortality. Life Sci. 2022, 310, 121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez García, H.A.; Wong, S.; Jeong, D.; Binka, M.; Naveed, Z.; Wilton, J.; Hawkins, N.M.; Janjua, N.Z. Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events After SARS-CoV-2 Infection in British Columbia: A Population-Based Study. Am. J. Med. 2025, 138, 524–531.e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeghy, R.E.; Stute, N.L.; Province, V.M.; Augenreich, M.A.; Stickford, J.L.; Stickford, A.S.L.; Ratchford, S.M. Six-Month Longitudinal Tracking of Arterial Stiffness and Blood Pressure in Young Adults Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Nasoufidou, A.; Sagris, M.; Fragakis, N.; Tsioufis, K. Vascular Alterations Following COVID-19 Infection: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Life 2024, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Mazzitelli, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Bilato, C.; Cattelan, A.M. Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients Recovered from COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Stroke J. 2023, 8, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins-Gonçalves, R.; Hottz, E.D.; Bozza, P.T. Acute to Post-Acute COVID-19 Thromboinflammation Persistence: Mechanisms and Potential Consequences. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, I.; Lumpuy-Castillo, J.; Magalhaes, G.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F.; Lorenzo, Ó.; Peiró, C. Mechanisms of Endothelial Activation, Hypercoagulation and Thrombosis in COVID-19: A Link with Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Tang, S.; Guo, J.; Gabriel, N.; Gellad, W.F.; Essien, U.R.; Magnani, J.W.; Hernandez, I. COVID-19 Diagnosis, Oral Anticoagulation, and Stroke Risk in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2024, 24, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Tan, X.; Li, T. The Potential Mechanisms of Arrhythmia in Coronavirus Disease-2019. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 21, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeeva, T.I.; Zbyshevskaya, E.V.; Mayer, M.V.; Talibov, F.A.; Saiganov, S.A. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia as a Manifestation of Acute Myocardial Injury. Card. Arrhythm. 2023, 3, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Hasimbegovic, E.; Schönbauer, R.; Beitzke, D.; Gyöngyösi, M. Combined Cardiac Arrhythmias Leading to Electrical Chaos Developed in the Convalescent Phase of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Nalroad Sundararaj, S.; Bhatia, J.; Singh Arya, D. Understanding Long COVID Myocarditis: A Comprehensive Review. Cytokine 2024, 178, 156584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, S.; Peker, E.; Bozer Uludağ, S.; Yılmazer Zorlu, S.N.; Ergüden, R.E.; Hekimoğlu, A.A. Cardiac MRI for COVID-19-Related Late Myocarditis: Functional Parameters and T1 and T2 Mapping. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fijalkowska, J.; Glinska, A.; Fijalkowski, M.; Sienkiewicz, K.; Kulawiak-Galaska, D.; Szurowska, E.; Pienkowska, J.; Dorniak, K. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Relaxometry Parameters, Late Gadolinium Enhancement, and Feature-Tracking Myocardial Longitudinal Strain in Patients Recovered from COVID-19. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.M.; Fudim, M.; O’Neil, S.T.; Manna, A.; Chute, C.G.; Caughey, M.C. Post-Recovery COVID-19 and Incident Heart Failure in the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Study. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohun, J.; Dorniak, K.; Faran, A.; Kochańska, A.; Zacharek, D.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L. Long COVID-19 Myocarditis and Various Heart Failure Presentations: A Case Series. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan, M.; Mirzohreh, S.T.; Kaviani, R.; Yousefi, S.; Pourmehran, Y. A Deeper Look at Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Myocardial Function in Survivors with No Prior Heart Diseases: A GRADE Approach Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1458389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideratou, C.M.; Papaneophytou, C. Persistent Vascular Complications in Long COVID: The Role of ACE2 Deactivation, Microclots, and Uniform Fibrosis. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, Y.; Alameer, A.; Calpin, G.; Alkhattab, M.; Sultan, S. A comprehensive review of vascular complications in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2022, 53, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M. ACE2 and COVID-19 Susceptibility and Severity. Aging. Dis. 2022, 13, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Barnett, J.; Brill, S.E.; Brown, J.S.; Denneny, E.K.; Hare, S.S.; Siddiqui, I.; Patel, I.; Freeman, A.; Jones, M.; et al. Long-COVID: A Cross-Sectional Study of Persisting Symptoms, Biomarker and Imaging Abnormalities Following Hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax 2021, 76, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, M.M.; Vandenbriele, C.; Balthazar, T.; Claeys, E.; Gunst, J.; Guler, I.; Vanassche, T.; Verhamme, P. Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Discharged After COVID-19 Hospitalization. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 47, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotelli, E.; Campitiello, R.; Pizzorni, C.; Sammorì, S.; Aitella, E.; Ginaldi, L.; De Angelis, R.; Paolino, S.; Cutolo, M.; Sulli, A. Multicentre Retrospective Detection of Nailfold Videocapillaroscopy Abnormalities in Long COVID Patients. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Fogarty, H.; Dyer, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Bannan, C.; Nadarajan, P.; Bergin, C.; O’Brien, M.; Thomas, S.; O’Connell, N.; et al. Prolonged Elevation of D-Dimer Levels in Convalescent COVID-19 Patients Is Independent of the Acute Phase Response. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charfeddine, S.; Ibn Hadj Amor, H.; Jallouli, M.; Lagha, R.; Thabet, A.; Kaabachi, N.; Kammoun, S.; Bahloul, A.; Fendri, S.; Ben Kahla, S.; et al. Long COVID-19 Syndrome: Is It Related to Microcirculation and Endothelial Dysfunction? Insights From the TUN-EndCOV Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 745758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H.; Karp Leaf, R.S.; Dzik, W.H.; Carlson, J.; Fogerty, A.E.; Waheed, A.; Goodarzi, K.; Singh, A.; Spriggs, D.R.; Brock, A.; et al. COVID-19 and Coagulation: Bleeding and Thrombotic Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Blood 2020, 136, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yu, C.; Jing, H.; Wu, X.; Novak, N.; Peng, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, G.; Wang, C. Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on the Cardiovascular System: A Review. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, G.K.; Kotagiri, R.; Chandiramohan, A.; Subramaniam, S.; Narasimhan, M.; Raghavan, V.; Ramakrishnan, N. COVID-19 and Coagulation Disorders: An Updated Review. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncati, L.; Nasillo, V.; Lusenti, B.; Riva, G. Signals of Thromboembolic Events in Long COVID Patients. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021, 59, e365–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. Reply to: “A Dermatologic Manifestation of COVID-19: Transient Livedo Reticularis”. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, e155–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gil, M.F.; Monte Serrano, J.; Lapeña-Casado, A.; García García, M.; Matovelle Ochoa, C.; Ara-Martín, M. Livedo Reticularis and Acrocyanosis as Late Manifestations of COVID-19 in Two Cases with Familial Aggregation. Potential Pathogenic Role of Complement (C4c). Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 1549–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Cong, B.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, S.; Yu, Z.; Xu, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Enhances Complement-Mediated Endothelial Injury Via the Suppression of Membrane Complement Regulatory Proteins. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2025, 14, 467781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.C.; Chuang, S.C.; Hung, K.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chuang, K.P.; Yuan, C.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Tsai, P.H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, S.C.; et al. Exploring Risk Factors for Raynaud’s Phenomenon Post COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PICOS Component | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | Adults (≥18 years) with Long COVID (LC), encompassing individuals with persistent or newly emerging symptoms or clinically relevant conditions following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. For search completeness, studies referring to post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) were included, provided that LC was the primary condition investigated. Eligible studies defined symptom persistence beyond 4 weeks after acute infection, while also incorporating those applying the WHO post-COVID-19 condition definition (≥12 weeks). |

| Intervention/Exposure/Context (I) | Post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, irrespective of initial disease severity or hospitalization status. |

| Comparator (C) | Healthy control individuals; individuals recovered from COVID-19 without reported long-term sequelae; or patients with other chronic conditions used as comparator groups (e.g., myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome). Studies without a comparator group were also considered when mechanistic outcomes were reported. |

| Outcomes (O) | One or more of the following outcomes: (1) markers of endothelial dysfunction (e.g., vascular reactivity, endothelial biomarkers); (2) evidence of coagulation or fibrinolytic abnormalities (e.g., D-dimer, fibrinogen, hypercoagulability assays); (3) markers of immunothrombosis (e.g., neutrophil extracellular traps, platelet activation markers, antiphospholipid antibodies); and/or (4) clinical thromboembolic events, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. |

| Study design (S) | Original human studies, including observational studies (prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies), clinical trials, and mechanistic or laboratory-based studies conducted in human participants. |

| Exclusion criteria | Case reports, editorials, narrative opinions, non-peer-reviewed preprints, animal-only studies, and non-English language publications. |

| Mechanism | Key Processes | Main Mediators | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial dysfunction | Direct endothelial infection via ACE2 receptors; loss of antithrombotic function | von Willebrand factor, factor VIII, endothelin-1 | Procoagulant state, microthrombosis |

| Inflammatory activation | Cytokine storm and expression of tissue factor on monocytes | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, tissue factor | Thrombin activation, increased coagulation |

| Platelet activation | Platelet activation and aggregation due to cytokines and endothelial damage | Thromboxane A2, serotonin, CD40L | Microthrombosis, platelet consumption |

| Immunothrombosis (NETs formation) | Neutrophil activation and formation of NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps, fibrin | Microangiopathic thrombosis |

| Imbalance of coagulation and fibrinolysis | Increased PAI-1, reduced plasmin activity | PAI-1, plasmin | Hypofibrinolytic state, fibrin accumulation |

| Autoimmune mechanisms | Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies | aCL, anti-β2GPI, LA | Arterial and venous thrombosis |

| Parameter | Change | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| D-dimer | ↑ elevated | Marker of fibrinolysis and microthrombosis; correlates with disease severity |

| Fibrinogen | ↑ early phase, ↓ late phase | Reflects inflammation and consumption |

| Prothrombin time | Normal → slightly prolonged | Partial consumption of coagulation factors |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | Normal or slightly shortened | Hypercoagulable state |

| Antithrombin | ↓ decreased | Consumption and decreased synthesis; reduced heparin efficacy |

| Platelets | Normal → mildly decreased | Consumption and activation |

| vWF and factor VIII | ↑ elevated | Endothelial activation and microangiopathy |

| ADAMTS13 | ↓ decreased | Imbalance with vWF, prothrombotic effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stojanovic, M.; Djuric, M.; Nenadic, I.; Bojic, S.; Andrijevic, A.; Popovic, A.; Pesic, S. Vascular Complications of Long COVID—From Endothelial Dysfunction to Systemic Thrombosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010433

Stojanovic M, Djuric M, Nenadic I, Bojic S, Andrijevic A, Popovic A, Pesic S. Vascular Complications of Long COVID—From Endothelial Dysfunction to Systemic Thrombosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010433

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojanovic, Maja, Marko Djuric, Irina Nenadic, Suzana Bojic, Ana Andrijevic, Aleksa Popovic, and Slobodan Pesic. 2026. "Vascular Complications of Long COVID—From Endothelial Dysfunction to Systemic Thrombosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010433

APA StyleStojanovic, M., Djuric, M., Nenadic, I., Bojic, S., Andrijevic, A., Popovic, A., & Pesic, S. (2026). Vascular Complications of Long COVID—From Endothelial Dysfunction to Systemic Thrombosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010433