Increased Intrahepatic Mast Cell Density in Liver Cirrhosis Due to MASLD and Other Non-Infectious Chronic Liver Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of the Participants

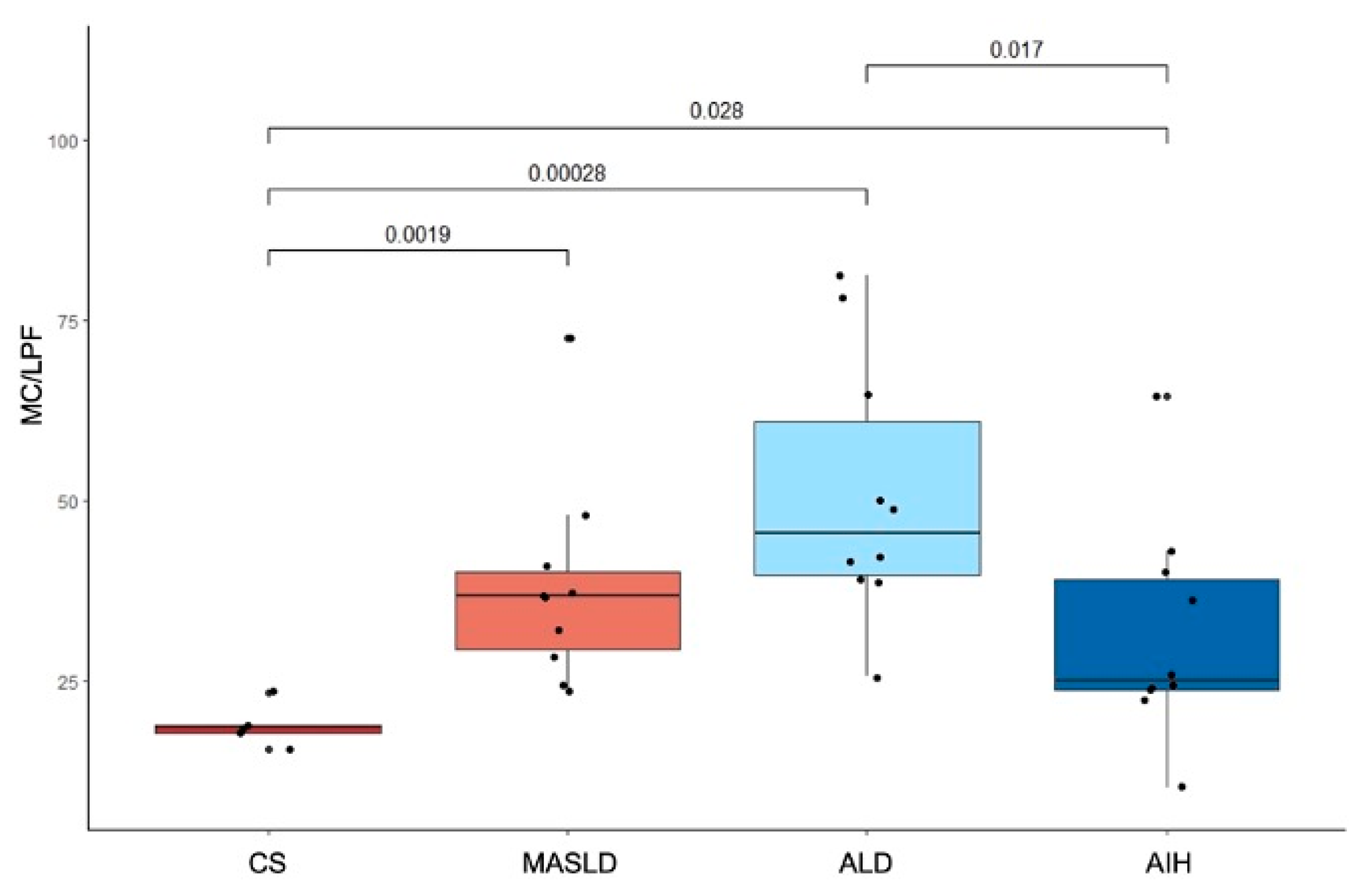

2.2. Differences in MC Density in Cirrhotic Liver Explants from Patients with MASLD, ALD, AIH, and CS

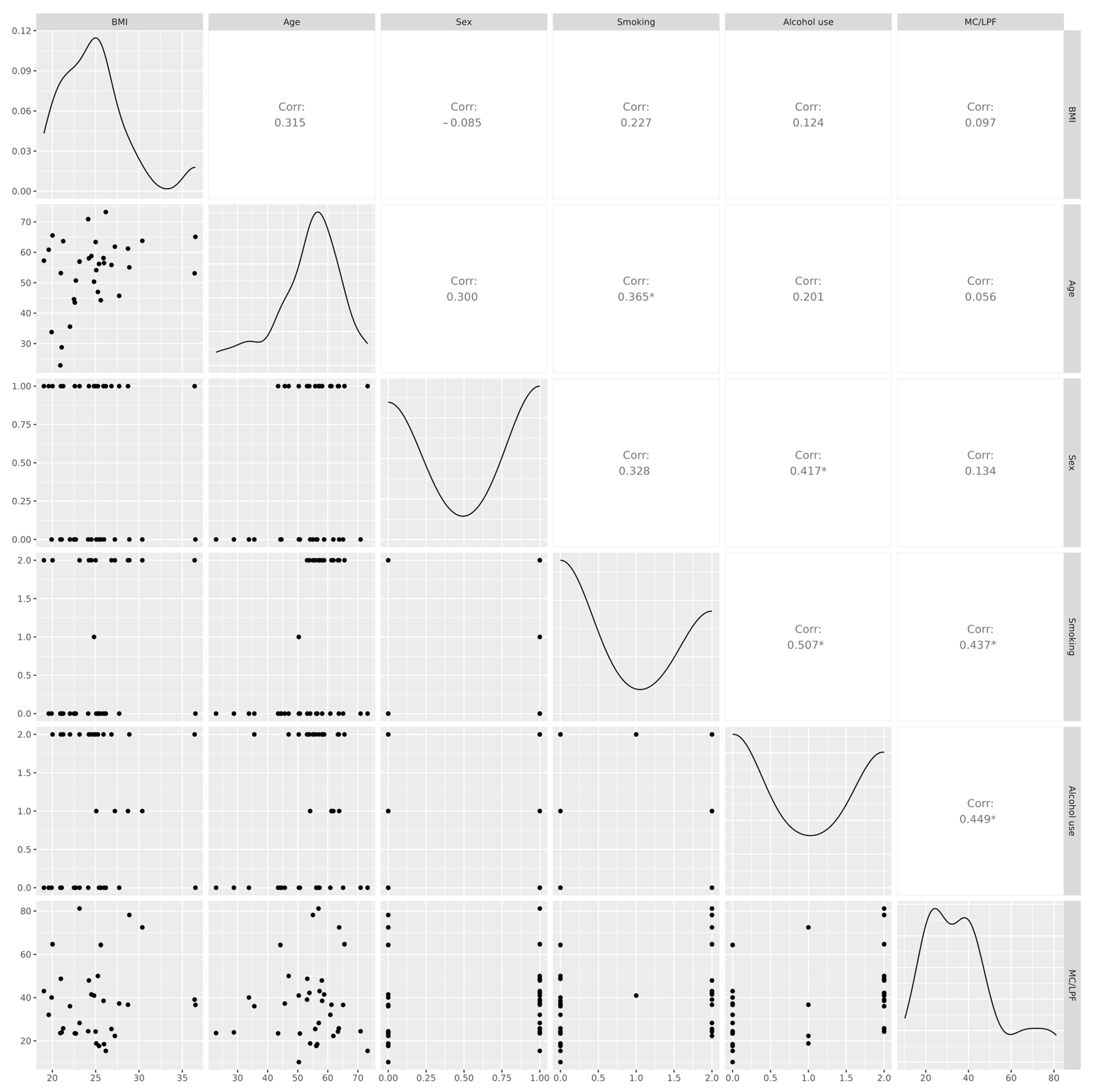

2.3. Correlation Between MC Density and Clinical Characteristics

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

4.2. Participants and Sampling

4.3. Preparation and Deparaffinization of Liver Tissue Samples

4.4. Indirect Immunofluorescence for MC Tryptase

4.5. MC Quantification

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Son, K.C.; Te Nijenhuis-Noort, L.C.; Boone, S.C.; Mook-Kanamori, D.O.; Holleboom, A.G.; Roos, P.R.; Lamb, H.; Alblas, G.; Coenraad, M.; Rosendaal, F.; et al. Prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in a middle-aged population with overweight and normal liver enzymes, and diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive proxies. Medicine 2024, 103, e34934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Adachi, H.; Hakoshima, M.; Iida, S.; Katsuyama, H. Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Its Pathophysiology, Association with Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Disease, and Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-López, N.; Ponce-Arancibia, S.; Aleman, L.; Roblero, J.P.; Urzua, A.; Cattaneo, M.; Poniachik, J. A General Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Liver Damage in Primary Health Care. Rev. Med. Chil. 2024, 152, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-López, N.; Fuenzalida, C.; Dufeu, M.S.; Pinto-León, A.; Escobar, A.; Poniachik, J.; Roblero, J.P.; Valenzuela-Pérez, L.; Beltrán, C.J. The immune response as a therapeutic target in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 954869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, H.; Gao, J.; Kong, X.; Che, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, E.; Xiao, J. Liver diseases: Epidemiology, causes, trends and predictions. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2025, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, H.; Luo, F.; Zhang, B.; Li, T.; Yang, Z.; Ren, B.; Yin, W.; Wu, D.; Tai, S. Exploring the role of mast cells in the progression of liver disease. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 964887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügle, T. Beyond allergy: The role of mast cells in fibrosis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2014, 144, w13999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, E.; Gao, K. Mast cells: A double-edged sword in inflammation and fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1466491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Friedman, S.L. Found in translation—Fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadi0759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarido, V.; Kennedy, L.; Hargrove, L.; Demieville, J.; Thomson, J.; Stephenson, K.; Francis, H. The emerging role of mast cells in liver disease. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2017, 313, G89–G101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Kennedy, L.; Baiocchi, L.; Meadows, V.; Ekser, B.; Kundu, D.; Zhou, T.; Sato, K.; Glaser, S.; Ceci, L.; et al. Mast cells in liver disease progression: An update on current studies and implications. Hepatology 2021, 75, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, N.M.; Fiancette, R.; Oo, Y.H. Interplay between Mast Cells and Regulatory T Cells in Immune-Mediated Cholangiopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, J.; Broadwater, D.; Collins, R.; Cebe, K.; Brady, R.; Harrison, S. Hepatic mast cell concentration directly correlates to stage of fibrosis in NASH. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 86, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, L.; Meadows, V.; Sybenga, A.; Demieville, J.; Chen, L.; Hargrove, L.; Ekser, B.; Dar, W.; Ceci, L.; Kundu, D.; et al. Mast Cells Promote Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Phenotypes and Microvesicular Steatosis in Mice Fed a Western Diet. Hepatology 2021, 74, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaoka, Y.; Jin, D.; Tashiro, K.; Komeda, K.; Masubuchi, S.; Hirokawa, F.; Hayashi, M.; Takai, S.; Uchiyama, K. Chymase inhibitor prevents the development and progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats fed a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 134, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, E.; Wosiak, A.; Zieliński, A.; Brzeziński, P.; Strzelczyk, J.; Szymański, D.; Kobos, J. Role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pol. J. Pathol. 2020, 71, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of autoimmune hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 453–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finotto, S.; Mekori, Y.A.; Metcalfe, D.D. Glucocorticoids decrease tissue mast cell number by reducing the production of the c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, by resident cells: In vitro and in vivo evidence in murine systems. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukinen, A.; Fitzgibbon, A.; Oikarinen, A.; Hinkkanen, L.; Viinikanoja, M.; Harvima, I.T. Increased numbers of tryptase-positive mast cells in the healthy and sun-protected skin of tobacco smokers. Dermatology 2014, 229, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Gou, G.; Wen, M.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Du, Q.; et al. Mast cells: Key players in digestive system tumors and their interactions with immune cells. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert-Bayo, M.; Paracuellos, I.; González-Castro, A.M.; Rodríguez-Urrutia, A.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Alonso-Cotoner, C.; Santos, J.; Vicario, M. Intestinal Mucosal Mast Cells: Key Modulators of Barrier Function and Homeostasis. Cells 2019, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, B.; Kamath, A.J.; Tergaonkar, V.; Sethi, G.; Nath, L.R. Mast cells and the gut-liver Axis: Implications for liver disease progression and therapy. Life Sci. 2024, 351, 122818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-López, N.; Madrid, A.M.; Aleman, L.; Zazueta, A.; Smok, G.; Valenzuela-Pérez, L.; Poniachik, J.; Beltrán, C.J. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in obese patients with biopsy-confirmed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1376148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, J.; Canioni, D.; Aouba, A.; Bulai-Livideanu, C.; Barete, S.; Lancesseur, C.; Polivka, L.; Madrange, M.; Ballul, T.; Neuraz, A.; et al. Histological characterization of liver involvement in systemic mastocytosis. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CS (n = 5) | MASLD (n = 10) | ALD (n = 10) | AIH (n = 10) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, IQR) | 56.2 (54.1–56.5) | 59.4 (50.3–63.8) | 55.4 (53.2–58.1) | 47.3 (33.8–61.9) | 0.400 |

| Male sex | 1 (20%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (80%) | 3 (30%) | 0.052 |

| BMI | 25.4 (25.1–26.0) | 24.5 (23.1–28.7) | 25.3 (23.1–26.8) | 21.3 (20.9–25.0) | 0.200 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Never | 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Suspended * | 1 | 4 | 10 | 4 | |

| Active | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 5 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 0.070 |

| Suspended * | 0 | 4 | 7 | 3 | |

| Active | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (mean, IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–3.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 4.0 (4.0–6.0) | 3.5 (3.0–6.0) | 0.010 |

| MELD score at liver transplant (mean, SD) | N/A | 23.2 ± 7.82 | 26.2 ± 5.65 | 26.4 ± 6.32 | 0.600 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ortiz-López, N.; Pinto-León, A.; Favi, J.; Guíñez Francois, D.; Aleman, L.; Carreño-Toro, L.; Zazueta, A.; Magne, F.; Poniachik, J.; Beltrán, C.J. Increased Intrahepatic Mast Cell Density in Liver Cirrhosis Due to MASLD and Other Non-Infectious Chronic Liver Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010392

Ortiz-López N, Pinto-León A, Favi J, Guíñez Francois D, Aleman L, Carreño-Toro L, Zazueta A, Magne F, Poniachik J, Beltrán CJ. Increased Intrahepatic Mast Cell Density in Liver Cirrhosis Due to MASLD and Other Non-Infectious Chronic Liver Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010392

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz-López, Nicolás, Araceli Pinto-León, Javiera Favi, Dannette Guíñez Francois, Larissa Aleman, Laura Carreño-Toro, Alejandra Zazueta, Fabien Magne, Jaime Poniachik, and Caroll J. Beltrán. 2026. "Increased Intrahepatic Mast Cell Density in Liver Cirrhosis Due to MASLD and Other Non-Infectious Chronic Liver Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010392

APA StyleOrtiz-López, N., Pinto-León, A., Favi, J., Guíñez Francois, D., Aleman, L., Carreño-Toro, L., Zazueta, A., Magne, F., Poniachik, J., & Beltrán, C. J. (2026). Increased Intrahepatic Mast Cell Density in Liver Cirrhosis Due to MASLD and Other Non-Infectious Chronic Liver Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010392