Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

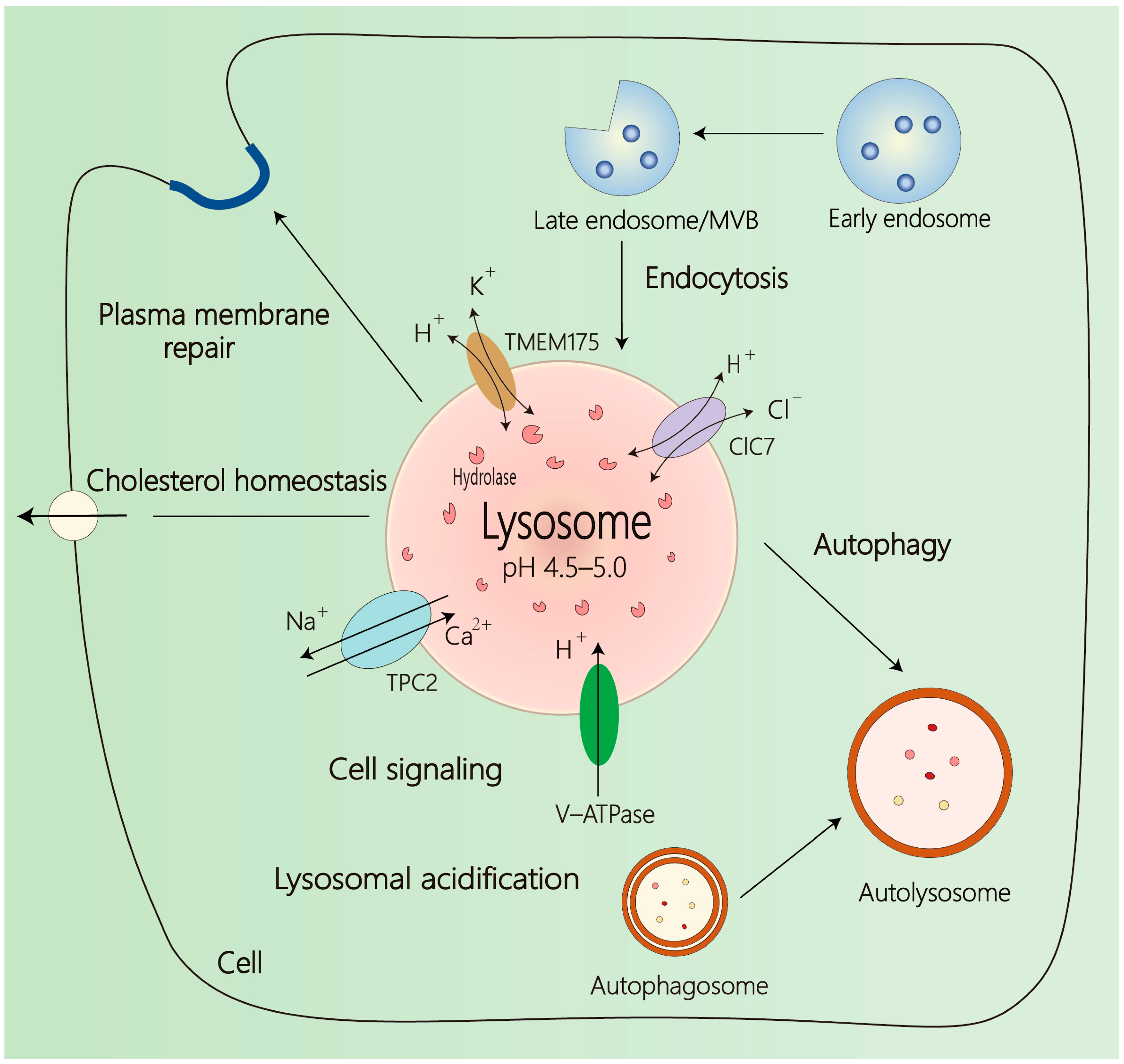

2. Overview of Lysosome

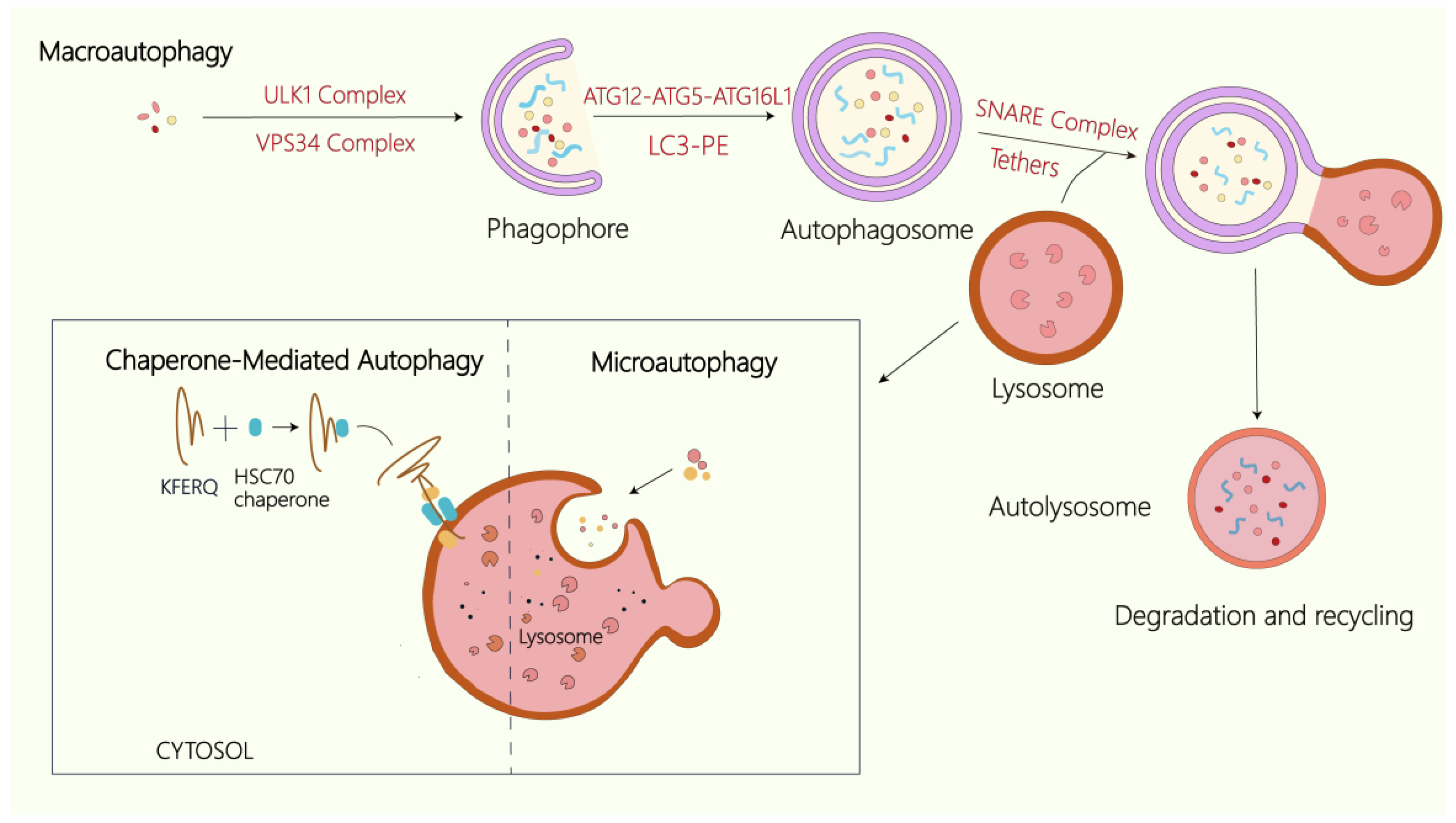

3. Overview of Autophagy

4. The Autophagy–Lysosome Axis: An Integrated Degradative Network

5. Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Diseases

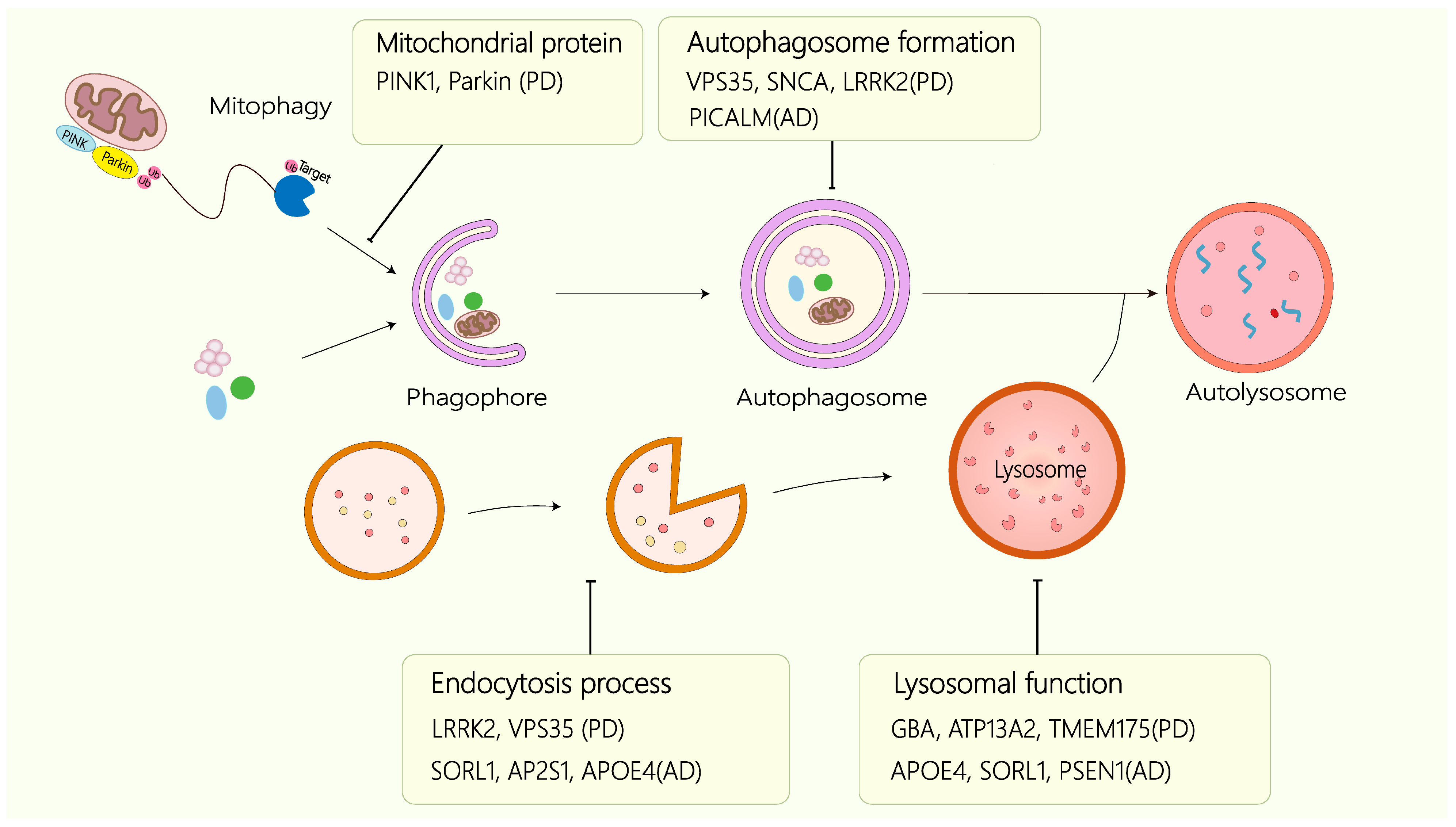

5.1. Neurodegenerative Diseases

5.1.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

5.1.2. Parkinson’s Disease

5.1.3. Huntington’s Disease

5.1.4. BPAN

5.2. Cancer

5.3. The Interaction Between Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cancer

6. Autophagy–Lysosome-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

| Target | Drug Name | Disease | Most Advanced Clinical Trials | NCT No./References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR | Rapamycin(Sirolimus) | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | FDA-approved | NCT00414648 | [116,117] |

| Lung cancer, Kidney cancer, Breast cancer, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Preclinical | - | |||

| Temsirolimus | Advanced renal cell cancer | FDA-approved | NCT00065468 | ||

| Everolimus | Renal cell cancer | FDA-approved | NCT00410124 | ||

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | NCT00510068 | ||||

| Breast cancer | NCT00863655 | ||||

| Epilepsy | NCT01713946 | ||||

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas | NCT00789828 | ||||

| Ridaforolimus | Sarcomas | III | NCT00538239 | ||

| GDC-0980 | Renal cell cancer | II | NCT01442090 | ||

| Endometrial cancer | II | NCT01455493 | |||

| Breast cancer | I | NCT01254526 | |||

| AMPK | Metformin | Type 2 diabetes | FDA-approved | NCT02252965 | [118,119] |

| Colorectal cancer | III | NCT05921942 | |||

| Breast cancer | III | NCT01101438 | |||

| AD | II | NCT01965756 | |||

| TFEB | Celastrol | AD, Gastric, Renal cell carcinoma | Preclinical | - | [122,123] |

| Trehalose | PD, HD | [124] | |||

| Curcumin analog C1 | AD | [148,149,150] | |||

| PF11 | AD | ||||

| PARP1 | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) inhibitors | AD, PD | Preclinical | - | [125] |

| Ovarian cancer | FDA-approved | NCT01844986 | |||

| Breast cancer | NCT01945775 | ||||

| Pancreatic cancer | NCT02184195 | ||||

| Prostate cancer | NCT05457257 | ||||

| TrxR1/2 | Hdy-7 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, Colorectal cancer, Lung cancer | Preclinical | - | [126] |

| PGRN | AL001 | AD | I/II | NCT05363293 | [127] |

| Lysosomal lumen alkalizer | Chloroquine (CQ) | Glioblastoma multiforme | III | NCT00224978 | [133,134] |

| Malaria | FDA-approved | NCT01814423 | |||

| ATG4B | UAMC-2526 | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical | - | [137,138,139,140,141] |

| NSC185058 | Osteosarcoma tumors | - | |||

| S130 | Colorectal cancer | - | |||

| ULK1 | SBI-0206965 | Renal cell cancer, Neuroblastoma | Preclinical | - | |

| ULK101 | Advanced cancers | - | |||

| VPS34 | VPS34-IN1 | Breast cancer, Acute myeloid leukemia, Non-small-cell lung cancer | Preclinical | - | |

| SAR405 | Kidney cancer, Melanoma, Colorectal cancer, Central nervous system tumors | - | |||

| 3-methyladenine (3-MA) | Colorectal cancer, Head and neck cancer | - | [135] | ||

| Lysosomal Ca2+ channel MCOLN3 | Baicalin | Non-small-cell lung cancer | Preclinical | - | [142] |

| σ-2 receptor | Siramesine | Pancreatic cancer | Preclinical | - | [144] |

| Small-cell lung cancer | - | ||||

| Lysosomal membrane | FV-429 | T-cell malignancies | Preclinical | - | [145] |

| Tetrandrine | AD | - | [148,149,150] | ||

| LRRK2 | DNL201 | PD | I | NCT03710707 | [146] |

| ClC7 | Isoproterenol (ISO) | AD | Preclinical | - | [147] |

| Atrioventricular Block, Shock | FDA-approved | - | |||

| V-ATPase | Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) | Leukemia, Glioblastoma | Preclinical | - | [136] |

| C381 | AD | [148,149,150] | |||

| NKH-477 | AD | ||||

| TRPML1 | SF-22 | AD | Preclinical | [148,149,150] | |

| SIRT1/SIRT3 | Nicotinamide riboside (NR) | AD | II | NCT05617508 | [148,149,150] |

| PD | NCT06853743 | ||||

| Breast cancer | II | NCT05732051 | |||

| Cathepsin Z(Ctsz) | Urolithin A (UA) | AD | Preclinical | - | [161] |

| Prostate cancer | II | NCT06022822 | |||

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Debnath, J.; Gammoh, N.; Ryan, K.M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Bourdenx, M.; Fujimaki, M.; Karabiyik, C.; Krause, G.J.; Lopez, A.; Martín-Segura, A.; Puri, C.; Scrivo, A.; Skidmore, J.; et al. The different autophagy degradation pathways and neurodegeneration. Neuron 2022, 110, 935–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.E.; Wilson, N.; Son, S.M.; Obrocki, P.; Wrobel, L.; Rob, M.; Takla, M.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Autophagy, aging, and age-related neurodegeneration. Neuron 2025, 113, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, B.A.; Hiesinger, P.R. Autophagy in synapse formation and brain wiring. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2814–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, C.; Cattaneo, M.G.; Molteni, R.; De Palma, C. Autophagy in the Regulation of Tissue Differentiation and Homeostasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 602901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Biological Functions of Autophagy Genes: A Disease Perspective. Cell 2019, 176, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runwal, G.; Stamatakou, E.; Siddiqi, F.H.; Puri, C.; Zhu, Y.; Rubinsztein, D.C. LC3-positive structures are prominent in autophagy-deficient cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, P.P.Y.; Nixon, R.A. Lysosome trafficking and signaling in health and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 122, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; White, E.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Breakthroughs and bottlenecks in autophagy research. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K.; Stransky, L.; McGuire, C.; Forgac, M. Recent Insights into the Structure, Regulation, and Function of the V-ATPases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.H.; Zeng, J. Defective lysosomal acidification: A new prognostic marker and therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, F.M.; d’Azzo, A.; Davidson, B.L.; Neufeld, E.F.; Tifft, C.J. Lysosomal storage diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yue, P.; Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Role of lysosomes in physiological activities, diseases, and therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, J.; Wang, G.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ouyang, L. Targeting Lysosomal Degradation Pathways: New Strategies and Techniques for Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 3493–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Chu, J.; Zhang, T.; Yin, T.; Gu, Y.; Liang, W.; Ji, W.; Zhuang, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. Nanomaterials-mediated lysosomal regulation: A robust protein-clearance approach for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftig, P.; Klumperman, J. Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: Trafficking meets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Richards, C.M.; Jabs, S. LYSET/TMEM251- a novel key component of the mannose 6-phosphate pathway. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2143–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, P.; Wang, C.; Feng, X.; Geng, Q.; Chen, W.; Marthi, M.; Zhang, W.; Gao, C.; Reid, W.; et al. Parkinson’s disease-risk protein TMEM175 is a proton-activated proton channel in lysosomes. Cell 2022, 185, 2292–2308.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Wen, N.; Cai, W.; Li, P.; Zhao, L.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yang, X.; et al. SLC7A11 is an unconventional H(+) transporter in lysosomes. Cell 2025, 188, 3441–3458.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, W.; Han, Y.; Lee, W.R.; Liou, J.; Jiang, Y. Lysosomal LAMP proteins regulate lysosomal pH by direct inhibition of the TMEM175 channel. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2524–2539.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; Perera, R.M. Lysosomes as coordinators of cellular catabolism, metabolic signalling and organ physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, F.; Wang, S.; Tian, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Fang, C.; Ma, C.; Rong, Y. The STX17-SNAP47-VAMP7/VAMP8 complex is the default SNARE complex mediating autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Guo, S.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Anoctamin 1 controls bone resorption by coupling Cl(-) channel activation with RANKL-RANK signaling transduction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; Levine, B.; Cuervo, A.M.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008, 451, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, Y.; Schmauck-Medina, T.; Hansen, M.; Morimoto, R.I.; Simon, A.K.; Bjedov, I.; Palikaras, K.; Simonsen, A.; Johansen, T.; Tavernarakis, N.; et al. Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavoe, A.K.H.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Autophagy in Neurons. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 35, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraes, F.V.; Niven, J.; Dubrot, J.; Hugues, S.; Gannagé, M. Macroautophagy in Endogenous Processing of Self- and Pathogen-Derived Antigens for MHC Class II Presentation. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, P.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.-F.; Lu, J.; Li, M.; Kurihara, H.; Luo, Z.; Meng, T.; Onishi, M.; et al. Selective autophagy of intracellular organelles: Recent research advances. Theranostics 2021, 11, 222–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, M.O.; Ichimura, Y.; Komatsu, M. Selective autophagy. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3972–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Cuervo, A.M. The coming of age of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oku, M.; Sakai, Y. Three Distinct Types of Microautophagy Based on Membrane Dynamics and Molecular Machineries. Bioessays 2018, 40, e1800008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Codogno, P.; Zhang, H. Machinery, regulation and pathophysiological implications of autophagosome maturation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Jung, C.H.; Seo, M.; Otto, N.M.; Grunwald, D.; Kim, K.H.; Moriarity, B.; Kim, Y.M.; Starker, C.; Nho, R.S.; et al. The ULK1 complex mediates MTORC1 signaling to the autophagy initiation machinery via binding and phosphorylating ATG14. Autophagy 2016, 12, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Skulsuppaisarn, M.; Strong, L.M.; Ren, X.; Lazarou, M.; Hurley, J.H.; Hummer, G. Three-step docking by WIPI2, ATG16L1, and ATG3 delivers LC3 to the phagophore. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, K.; Ulferts, R.; Jacquin, E.; Veith, T.; Gammoh, N.; Arasteh, J.M.; Mayer, U.; Carding, S.R.; Wileman, T.; Beale, R.; et al. The WD40 domain of ATG16L1 is required for its non-canonical role in lipidation of LC3 at single membranes. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e97840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Miao, G.; Xue, X.; Guo, X.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; Feng, D.; Hu, J.; et al. The Vici Syndrome Protein EPG5 Is a Rab7 Effector that Determines the Fusion Specificity of Autophagosomes with Late Endosomes/Lysosomes. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubas, A.; Karantanou, C.; Popovic, D.; Tascher, G.; Hoffmann, M.E.; Platzek, A.; Dawe, N.; Dikic, I.; Krause, D.S.; McEwan, D.G. The endolysosomal adaptor PLEKHM1 is a direct target for both mTOR and MAPK pathways. FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 864–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florey, O. TECPR1 helps bridge the CASM during lysosome damage. EMBO J 2023, 42, e115210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Tong, M.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, X. Human YKT6 forms priming complex with STX17 and SNAP29 to facilitate autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, D.G.; Popovic, D.; Gubas, A.; Terawaki, S.; Suzuki, H.; Stadel, D.; Coxon, F.P.; Miranda de Stegmann, D.; Bhogaraju, S.; Maddi, K.; et al. PLEKHM1 regulates autophagosome-lysosome fusion through HOPS complex and LC3/GABARAP proteins. Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szinyákovics, J.; Keresztes, F.; Kiss, E.A.; Falcsik, G.; Vellai, T.; Kovács, T. Potent New Targets for Autophagy Enhancement to Delay Neuronal Ageing. Cells 2023, 12, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varland, S.; Silva, R.D.; Kjosås, I.; Faustino, A.; Bogaert, A.; Billmann, M.; Boukhatmi, H.; Kellen, B.; Costanzo, M.; Drazic, A.; et al. N-terminal acetylation shields proteins from degradation and promotes age-dependent motility and longevity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghetti, G.; Skobo, T.; Chrisam, M.; Facchinello, N.; Fontana, C.M.; Bellesso, S.; Sabatelli, P.; Raggi, F.; Cecconi, F.; Bonaldo, P.; et al. The epg5 knockout zebrafish line: A model to study Vici syndrome. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1438–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Esposito, A.; Napolitano, G.; Ballabio, A.; Hurley, J.H. Structural basis for mTORC1 activation on the lysosomal membrane. Nature 2025, 647, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Wu, X.; Yin, D.; Jia, X.H.; Chen, X.; Gu, Z.Y.; Zhu, X.M. Autophagy inhibitors for cancer therapy: Small molecules and nanomedicines. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 249, 108485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, J.A.; Diab, H.I.; Lishu, L.; Jeong, A.L.; Patange, S.; Raben, N.; Puertollano, R. The nutrient-responsive transcription factor TFE3 promotes autophagy, lysosomal biogenesis, and clearance of cellular debris. Sci. Signal 2014, 7, ra9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Yu, D. Dissecting the multifaced function of transcription factor EB (TFEB) in human diseases: From molecular mechanism to pharmacological modulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 215, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Dion, W.A.; Yang, H.; Xun, J.; Kim, D.H.; Zhu, B.; Tan, J.X. A TBK1-independent primordial function of STING in lysosomal biogenesis. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 3979–3996.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Qian, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Song, L.; He, Z.; Liu, W.; Wan, W. The cGAS-STING pathway activates transcription factor TFEB to stimulate lysosome biogenesis and pathogen clearance. Immunity 2025, 58, 309–325.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhitomirsky, B.; Yunaev, A.; Kreiserman, R.; Kaplan, A.; Stark, M.; Assaraf, Y.G. Lysosomotropic drugs activate TFEB via lysosomal membrane fluidization and consequent inhibition of mTORC1 activity. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Ponpuak, M.; Mudd, M.H.; Kimura, T.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Mandell, M.; Bruun, J.A.; et al. TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2016, 39, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, H.; Tabata, K.; Saeki, M.; Umemoto, T.; Hatta, T.; Otomo, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Natsume, T.; Yoshimori, T.; Hamasaki, M. Identification of CUL4A-DDB1-WDFY1 as an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex involved in initiation of lysophagy. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, M. Calcium Signalling in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Pathophysiological Regulation to Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2021, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A. Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.C.; Vest, R.; Prado, M.A.; Wilson-Grady, J.; Paulo, J.A.; Shibuya, Y.; Moran-Losada, P.; Lee, T.T.; Luo, J.; Gygi, S.P.; et al. Proteostasis and lysosomal repair deficits in transdifferentiated neurons of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yang, D.S.; Goulbourne, C.N.; Im, E.; Stavrides, P.; Pensalfini, A.; Chan, H.; Bouchet-Marquis, C.; Bleiwas, C.; Berg, M.J.; et al. Faulty autolysosome acidification in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models induces autophagic build-up of Aβ in neurons, yielding senile plaques. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretou, M.; Sannerud, R.; Escamilla-Ayala, A.; Leroy, T.; Vrancx, C.; Van Acker, Z.P.; Perdok, A.; Vermeire, W.; Vorsters, I.; Van Keymolen, S.; et al. Accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments causes endolysosomal dysfunction through the dysregulation of late endosome to lysosome-ER contact sites. Dev. Cell 2024, 59, 1571–1592.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Tuck, E.; Stubbs, V.; van der Lee, S.J.; Aalfs, C.; van Spaendonk, R.; Scheltens, P.; Hardy, J.; Holstege, H.; Livesey, F.J. SORL1 deficiency in human excitatory neurons causes APP-dependent defects in the endolysosome-autophagy network. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.S.; Miranda, R.D.; Newhouse, Y.M.; Weisgraber, K.H.; Huang, Y.; Mahley, R.W. Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid beta peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21821–21828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.X.; Luo, B.; Xie, X.Y.; Zhou, G.F.; Chen, J.; Song, L.; Liu, Y.; Xie, S.Q.; Chen, L.; Li, K.Y.; et al. AP2S1 regulates APP degradation through late endosome-lysosome fusion in cells and APP/PS1 mice. Traffic 2023, 24, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Huang, W.; Zhang, P.; Shi, J.; Yu, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Critical role of ROCK1 in AD pathogenesis via controlling lysosomal biogenesis and acidification. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradian, S.H.; Lewis, A.J.; Genoud, C.; Hench, J.; Moors, T.E.; Navarro, P.P.; Castaño-Díez, D.; Schweighauser, G.; Graff-Meyer, A.; Goldie, K.N.; et al. Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet-Ponce Ph, D.L.; Cookson, M.R. Can Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 Inhibition Benefit GBA-Parkinson’s Disease? Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Ping, M.; Liu, H.; Yu, T.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Hou, X.; Chu, Q.; Li, S.; et al. Structural insights into the activation of TMEM175 by small molecule. Neuron 2025, 113, 3567–3581.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobny, A.; Boros, F.A.; Balta, D.; Prieto Huarcaya, S.; Caylioglu, D.; Qazi, N.; Vandrey, J.; Schneider, Y.; Dobert, J.P.; Pitcairn, C.; et al. Reciprocal effects of alpha-synuclein aggregation and lysosomal homeostasis in synucleinopathy models. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Li, Y.; Hattori, N. Lysosomal defects in ATP13A2 and GBA associated familial Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Ash, P.E.; Gowda, V.; Liu, L.; Shirihai, O.; Wolozin, B. Mutations in LRRK2 potentiate age-related impairment of autophagic flux. Mol. Neurodegener. 2015, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, A.R.; Chen, C.W.; Corrochano, S.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; Gordon, D.E.; Peden, A.A.; Lichtenberg, M.; Menzies, F.M.; Ravikumar, B.; Imarisio, S.; et al. α-Synuclein impairs macroautophagy: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhao, M.; Wang, D.; Sun, Z.; Wen, P.; Dai, Y.; Gou, F.; Ji, Y.; et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 84, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilina, A.; Bonet-Ponce, L.; Kumaran, R.; Kordich, J.J.; Ishida, M.; Mamais, A.; Kaganovich, A.; Saez-Atienzar, S.; Gershlick, D.C.; Roosen, D.A.; et al. The Parkinson’s Disease Protein LRRK2 Interacts with the GARP Complex to Promote Retrograde Transport to the trans-Golgi Network. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Almeida, S.; Prudencio, M.; Caulfield, T.R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Tay, W.M.; Bauer, P.O.; Chew, J.; Sasaguri, H.; Jansen-West, K.R.; et al. Targeted manipulation of the sortilin-progranulin axis rescues progranulin haploinsufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, P.; Taylor, M.; Lam, P.Y.; Tonelli, F.; Hecht, C.A.; Lis, P.; Nirujogi, R.S.; Phung, T.K.; Yeshaw, W.M.; Jaimon, E.; et al. Parkinson’s VPS35[D620N] mutation induces LRRK2-mediated lysosomal association of RILPL1 and TMEM55B. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadj1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajkovic, K.; Jeong, H.; Krainc, D. Mutant Huntingtin Is Secreted via a Late Endosomal/Lysosomal Unconventional Secretory Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 9000–9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erie, C.; Sacino, M.; Houle, L.; Lu, M.L.; Wei, J. Altered lysosomal positioning affects lysosomal functions in a cellular model of Huntington’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2015, 42, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.M.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, W.K.; Chen, S.; Church, V.A.; Cates, K.; Li, T.; Zhang, B.; Dolle, R.E.; Dahiya, S.; et al. Age-related Huntington’s disease progression modeled in directly reprogrammed patient-derived striatal neurons highlights impaired autophagy. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, C. Targeting the autophagy-lysosomal pathway in Huntington disease: A pharmacological perspective. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1175598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, S.; Christodoulou, K.; Anastasiadou, V.; Nicolaides, P. Early-onset presentation of a new subtype of β-Propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) caused by a de novo WDR45 deletion in a 6 year-old female patient. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 63, 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneubourg, C.; Ramm, M.; Smith, L.J.; Baron, O.; Singh, K.; Byrne, S.C.; Duchen, M.R.; Gautel, M.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Fanto, M.; et al. The spectrum of neurodevelopmental, neuromuscular and neurodegenerative disorders due to defective autophagy. Autophagy 2022, 18, 496–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.L.; Gregory, A.; Kurian, M.A.; Bushlin, I.; Mochel, F.; Emrick, L.; Adang, L.; Hogarth, P.; Hayflick, S.J. Consensus clinical management guideline for beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2021, 63, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almannai, M.; Marafi, D.; El-Hattab, A.W. WIPI proteins: Biological functions and related syndromes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1011918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhao, Y.G. The BPAN and intellectual disability disease proteins WDR45 and WDR45B modulate autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 2021, 17, 1783–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aring, L.; Choi, E.K.; Kopera, H.; Lanigan, T.; Iwase, S.; Klionsky, D.J.; Seo, Y.A. A neurodegeneration gene, WDR45, links impaired ferritinophagy to iron accumulation. J. Neurochem. 2022, 160, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibler, P.; Burbulla, L.F.; Dulovic, M.; Zittel, S.; Heine, J.; Schmidt, T.; Rudolph, F.; Westenberger, A.; Rakovic, A.; Münchau, A.; et al. Iron overload is accompanied by mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in WDR45 mutant cells. Brain 2018, 141, 3052–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloedjes, T.A.; de Wilde, G.; Guikema, J.E.J. Metabolic Effects of Recurrent Genetic Aberrations in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2021, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; You, Q.; Hou, K.; Tian, Y.; Wei, P.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, B.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Aref, A.R.; Kalbasi, A.; et al. Autophagy in cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2025, 78, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Jackson, S.; Seaman, M.; Brown, K.; Kempkes, B.; Hibshoosh, H.; Levine, B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999, 402, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Yu, J.; Bhagat, G.; Furuya, N.; Hibshoosh, H.; Troxel, A.; Rosen, J.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Mizushima, N.; Ohsumi, Y.; et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangež, Ž.; Gérard, D.; He, Z.; Gavriil, M.; Fernández-Marrero, Y.; Seyed Jafari, S.M.; Hunger, R.E.; Lucarelli, P.; Yousefi, S.; Sauter, T.; et al. ATG5 and ATG7 Expression Levels Are Reduced in Cutaneous Melanoma and Regulated by NRF1. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 721624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.R.; Kim, M.S.; Oh, J.E.; Kim, Y.R.; Song, S.Y.; Kim, S.S.; Ahn, C.H.; Yoo, N.J.; Lee, S.H. Frameshift mutations of autophagy-related genes ATG2B, ATG5, ATG9B and ATG12 in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. J. Pathol. 2009, 217, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Pham, V.T.; Fu, S.; Huang, G.; Liu, Y.G.; Zheng, L. Mitophagy’s impacts on cancer and neurodegenerative diseases: Implications for future therapies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, F.; Servais, S.; Besson, P.; Roger, S.; Dumas, J.F.; Brisson, L. Autophagy and mitophagy in cancer metabolic remodelling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 98, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Wen, Q.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Kroemer, G.; et al. PINK1 and PARK2 Suppress Pancreatic Tumorigenesis through Control of Mitochondrial Iron-Mediated Immunometabolism. Dev. Cell 2018, 46, 441–455.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.; Golbourn, B.; Huang, X.; Remke, M.; Younger, S.; Cairns, R.A.; Chalil, A.; Smith, C.A.; Krumholtz, S.L.; Mackenzie, D.; et al. PINK1 Is a Negative Regulator of Growth and the Warburg Effect in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4708–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.H.; Tracy, K.; Frankenberger, C.; Boland, M.L.; Sharifi, M.N.; Drake, L.E.; Sachleben, J.R.; Asara, J.M.; Locasale, J.W.; Karczmar, G.S.; et al. Mitophagy defects arising from BNip3 loss promote mammary tumor progression to metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsli-Uzunbas, G.; Guo, J.Y.; Price, S.; Teng, X.; Laddha, S.V.; Khor, S.; Kalaany, N.Y.; Jacks, T.; Chan, C.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; et al. Autophagy is required for glucose homeostasis and lung tumor maintenance. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Luo, X.; Wu, K.; He, X. Targeting lysosomes in human disease: From basic research to clinical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Yin, Y.; Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W. Prevention of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma by Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañeque, T.; Baron, L.; Müller, S.; Carmona, A.; Colombeau, L.; Versini, A.; Solier, S.; Gaillet, C.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Sampaio, J.L.; et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature 2025, 642, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegeli, K.M.; Hastie, E.; Garde, A.; Wang, Z.; Keeley, D.P.; Gordon, K.L.; Pani, A.M.; Kelley, L.C.; Morrissey, M.A.; Chi, Q.; et al. Cell Invasion In Vivo via Rapid Exocytosis of a Transient Lysosome-Derived Membrane Domain. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 403–417.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Tian, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zeng, W.; Ye, Y.; He, M.; Ni, X.; Pan, J.; et al. CCDC50 promotes tumor growth through regulation of lysosome homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e56948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, H. Common mechanisms of onset of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 38, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Park, M. Molecular crosstalk between cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2659–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yoo, J.M.; Li, Y.; Heo, Y.; Okumura, M.; Won, H.S.; Vendruscolo, M.; Lim, M.H.; Lee, Y.H. Disease-disease interactions: Molecular links of neurodegenerative diseases with cancer, viral infections, and type 2 diabetes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2025, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Nie, J.; Ma, X.; Wei, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting PI3K in cancer: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F.; Butterfield, D.A. mTOR signaling in aging and neurodegeneration: At the crossroad between metabolism dysfunction and impairment of autophagy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 84, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pan, C.; Bei, J.X.; Li, B.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.; Fu, X. Mutant p53 in Cancer Progression and Targeted Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 595187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, F.D.; Martiniuk, F.; Marcus, D.L.; Frey, W.H., 2nd; Hite, R.; Bordayo, E.Z.; Freedman, M.L. Apoptotic gene expression in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampal tissue. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2007, 22, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uberti, D.; Lanni, C.; Carsana, T.; Francisconi, S.; Missale, C.; Racchi, M.; Govoni, S.; Memo, M. Identification of a mutant-like conformation of p53 in fibroblasts from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohyagi, Y.; Asahara, H.; Chui, D.H.; Tsuruta, Y.; Sakae, N.; Miyoshi, K.; Yamada, T.; Kikuchi, H.; Taniwaki, T.; Murai, H.; et al. Intracellular Abeta42 activates p53 promoter: A pathway to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostendorf, B.N.; Bilanovic, J.; Adaku, N.; Tafreshian, K.N.; Tavora, B.; Vaughan, R.D.; Tavazoie, S.F. Common germline variants of the human APOE gene modulate melanoma progression and survival. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Motolese, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Caraci, F.; Copani, A.; Nicoletti, F.; Terstappen, G.C.; Gaviraghi, G.; Caricasole, A. Inhibition of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by apolipoprotein E4 in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plun-Favreau, H.; Lewis, P.A.; Hardy, J.; Martins, L.M.; Wood, N.W. Cancer and neurodegeneration: Between the devil and the deep blue sea. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifati, V.; Rizzu, P.; van Baren, M.J.; Schaap, O.; Breedveld, G.J.; Krieger, E.; Dekker, M.C.; Squitieri, F.; Ibanez, P.; Joosse, M.; et al. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science 2003, 299, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, L.D.; Johansen, S.K.; Okarmus, J.; Meyer, M. Pathogenesis of DJ-1/PARK7-Mediated Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, J.M.; Zhou, J.Y.; Wu, G.S. Autophagy and cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2024, 605, 217285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, O.; Fouad, M. Risk of oral and gastrointestinal mucosal injury in patients with solid tumors treated with everolimus, temsirolimus or ridaforolimus: A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2015, 15, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, S.; Xian, H.; Che, H.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Bai, Y.; et al. Metformin Inhibits the NLRP3 Inflammasome via AMPK/mTOR-dependent Effects in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, L.; Bailey-Whyte, M.; Bhattacharya, M.; Butera, G.; Hardell, K.N.L.; Seidenberg, A.B.; Castle, P.E.; Loomans-Kropp, H.A. Association of metformin use and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Kamarudin, M.N.A.; Naidu, R. Anticancer Mechanism of Curcumin on Human Glioblastoma. Nutrients 2021, 13, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Cen, X.; Shan, B.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T.; Wang, Z.; Hou, T.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Metformin activates chaperone-mediated autophagy and improves disease pathologies in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Pi, W.; Huang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Yao, S.; Lin, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Orchestrated metal-coordinated carrier-free celastrol hydrogel intensifies T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade for synergistic chemo-immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2025, 312, 122723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, B.; Ibrahim, E.A.; Moselhy, S.S.; ElShebiney, S.; Elabd, W.K. Phytochemical based on nanoparticles for neurodegenerative alzheimer disease management: Update review. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmini, P.; Cortese, K.; Crippa, V.; Cristofani, R.; Cicardi, M.E.; Ferrari, V.; Vezzoli, G.; Tedesco, B.; Meroni, M.; Messi, E.; et al. Trehalose induces autophagy via lysosomal-mediated TFEB activation in models of motoneuron degeneration. Autophagy 2019, 15, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delint-Ramirez, I.; Madabhushi, R. DNA damage and its links to neuronal aging and degeneration. Neuron 2025, 113, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Niu, Z.; Gu, Z.; Fei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hao, X. Isowalsuranolide targets TrxR1/2 and triggers lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy via the p53-TFEB/TFE3 axis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 1437–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budda, B.; Mitra, A.; Park, L.; Long, H.; Kurnellas, M.; Bien-Ly, N.; Estacio, W.; Burgess, B.; Chao, G.; Schwabe, T.; et al. Development of AL101 (GSK4527226), a progranulin-elevating monoclonal antibody, as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, E.; Giráldez, S.; Sánchez-Aguayo, I.; Romero, F.; Ruano, D.; Daza, P. Breast cancer cell line MCF7 escapes from G1/S arrest induced by proteasome inhibition through a GSK-3β dependent mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Puebla, A.; Boya, P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization as a cell death mechanism in cancer cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, M.; Orhon, I.; Rocchi, C.; Zhou, X.; Luhr, M.; Hijlkema, K.J.; Coppes, R.P.; Engedal, N.; Mari, M.; Reggiori, F. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1435–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.B.; Hui, B.; Shi, Y.H.; Zhou, J.; Peng, Y.F.; Gu, C.Y.; Yang, H.; Shi, G.M.; Ke, A.W.; Wang, X.Y.; et al. Autophagy activation in hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the tolerance of oxaliplatin via reactive oxygen species modulation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6229–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boya, P.; Gonzalez-Polo, R.A.; Poncet, D.; Andreau, K.; Vieira, H.L.; Roumier, T.; Perfettini, J.L.; Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization is a critical step of lysosome-initiated apoptosis induced by hydroxychloroquine. Oncogene 2003, 22, 3927–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, S.; Fadhil, W.; Murtaza, S.; Hassall, J.C.; Ebili, H.O.; Oniscu, A.; Ilyas, M. Positive association of PIK3CA mutation with KRAS mutation but not BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer suggests co-selection is gene specific but not pathway specific. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 72, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy Levy, J.M.; Zahedi, S.; Griesinger, A.M.; Morin, A.; Davies, K.D.; Aisner, D.L.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Fitzwalter, B.E.; Goodall, M.L.; Thorburn, J.; et al. Autophagy inhibition overcomes multiple mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibition in brain tumors. eLife 2017, 6, e19671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, J.; Roh, J.L. RITA plus 3-MA overcomes chemoresistance of head and neck cancer cells via dual inhibition of autophagy and antioxidant systems. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, N.; Song, L.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Cao, Y.; Xu, F.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; et al. Bafilomycin A1 targets both autophagy and apoptosis pathways in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2015, 100, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, D.F.; Chun, M.G.; Vamos, M.; Zou, H.; Rong, J.; Miller, C.J.; Lou, H.J.; Raveendra-Panickar, D.; Yang, C.C.; Sheffler, D.J.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of the Autophagy Kinase ULK1 and Identification of ULK1 Substrates. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianniciello, A.; Zarou, M.M.; Rattigan, K.M.; Scott, M.; Dawson, A.; Dunn, K.; Brabcova, Z.; Kalkman, E.R.; Nixon, C.; Michie, A.M.; et al. ULK1 inhibition promotes oxidative stress-induced differentiation and sensitizes leukemic stem cells to targeted therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bago, R.; Malik, N.; Munson, M.J.; Prescott, A.R.; Davies, P.; Sommer, E.; Shpiro, N.; Ward, R.; Cross, D.; Ganley, I.G.; et al. Characterization of VPS34-IN1, a selective inhibitor of Vps34, reveals that the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-binding SGK3 protein kinase is a downstream target of class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 2014, 463, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronan, B.; Flamand, O.; Vescovi, L.; Dureuil, C.; Durand, L.; Fassy, F.; Bachelot, M.F.; Lamberton, A.; Mathieu, M.; Bertrand, T.; et al. A highly potent and selective Vps34 inhibitor alters vesicle trafficking and autophagy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Tagawa, Y.; Yoshimori, T.; Moriyama, Y.; Masaki, R.; Tashiro, Y. Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 1998, 23, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, D.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Jin, M.; Huang, G. Baicalin induces cell death of non-small cell lung cancer cells via MCOLN3-mediated lysosomal dysfunction and autophagy blockage. Phytomedicine 2024, 133, 155872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halaby, R. Natural Products Induce Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization as an Anticancer Strategy. Medicines 2021, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.P.; Alcalá, S.; Rico-Ferreira, M.D.R.; Hernández-Encinas, E.; García, J.; Albarrán, M.I.; Valle, S.; Muñoz, J.; Martínez-González, S.; Blanco-Aparicio, C.; et al. Induction of Lysosome Membrane Permeabilization as a Therapeutic Strategy to Target Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, J.; Qing, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Yu, X.; Hui, H.; Guo, Q.; Xu, J. FV-429 induces autophagy blockage and lysosome-dependent cell death of T-cell malignancies via lysosomal dysregulation. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.; Huntwork-Rodriguez, S.; Henry, A.G.; Sasaki, J.C.; Meisner, R.; Diaz, D.; Solanoy, H.; Wang, X.; Negrou, E.; Bondar, V.V.; et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of the LRRK2 inhibitor DNL201 for Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabj2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Wolfe, D.M.; Darji, S.; McBrayer, M.K.; Colacurcio, D.J.; Kumar, A.; Stavrides, P.; Mohan, P.S.; Nixon, R.A. β2-adrenergic Agonists Rescue Lysosome Acidification and Function in PSEN1 Deficiency by Reversing Defective ER-to-lysosome Delivery of ClC-7. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 2633–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Wang, X.; Dong, W.; Tang, Y.; Shah, N.; Shuai, S.; et al. Modulation of Ryanodine Receptors on Microglial Ramification, Migration, and Phagocytosis in an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Neurosci. Bull. 2025, 41, 2063–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, H.; Liu, Y.; Reiken, S.; Liu, X.; Argyrousi, E.K.; Yuan, Q.; Miotto, M.C.; Sittenfeld, L.; Meddar, A.; Soni, R.K.; et al. Heart failure-induced cognitive dysfunction is mediated by intracellular Ca2+ leak through ryanodine receptor type 2. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.G.; Liang, Y.L.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.T.; Gao, W.; Ye, Q.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.L. The evolution of Alzheimer’s disease: From mitochondria to microglia. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 111, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, M.; Corrigan, I.; Ramtoola, Z. Influence of particle size and dissolution conditions on the degradation properties of polylactide-co-glycolide particles. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévot, G.; Soria, F.N.; Thiolat, M.L.; Daniel, J.; Verlhac, J.B.; Blanchard-Desce, M.; Bezard, E.; Barthélémy, P.; Crauste-Manciet, S.; Dehay, B. Harnessing Lysosomal pH through PLGA Nanoemulsion as a Treatment of Lysosomal-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Bioconjug Chem. 2018, 29, 4083–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Acin-Perez, R.; Assali, E.A.; Martin, A.; Brownstein, A.J.; Petcherski, A.; Fernández-Del-Rio, L.; Xiao, R.; Lo, C.H.; Shum, M.; et al. Restoration of lysosomal acidification rescues autophagy and metabolic dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, E.; Chen, X.; Linkermann, A.; Jiang, X.; Kang, R.; Kagan, V.E.; Bayir, H.; Yang, W.S.; Garcia-Saez, A.J.; Ioannou, M.S.; et al. A guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimoto, Y.; Kusakabe, D.; Morimoto, K.; Matsuoka, Y.; Kozakura, E.; Kato, N.; Tsunematsu, K.; Umeno, T.; Kiyotani, T.; Matsumoto, S.; et al. Lysosomal lipid peroxidation contributes to ferroptosis induction via lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Abarientos, A.; Hong, J.; Hashemi, S.H.; Yan, R.; Dräger, N.; Leng, K.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B.; Xu, K.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPRi/a screens in human neurons link lysosomal failure to ferroptosis. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Mei, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H.; Sharma, S.; Liao, A.; Liu, C. Targeted Degradation Technology Based on the Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway: A Promising Strategy for Treating Preeclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2025, 93, e70066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wang, R.; You, Q.; Wang, L. Beyond Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeric Molecules: Designing Heterobifunctional Molecules Based on Functional Effectors. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8091–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, Z.; Luo, S.; Ding, Y.; Lu, B. Degradation of lipid droplets by chimeric autophagy-tethering compounds. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, P.; Bourdenx, M.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; Tiano, S.; Diaz, A.; Bartholdy, B.A.; Will, B.; Cuervo, A.M. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperone-mediated autophagy targeting motifs. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Chu, X.; Park, J.H.; Zhu, Q.; Hussain, M.; Li, Z.; Madsen, H.B.; Yang, B.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Urolithin A improves Alzheimer’s disease cognition and restores mitophagy and lysosomal functions. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 4212–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, M.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, C. Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010366

Du M, Yu Y, Wang J, Ji C. Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010366

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Mingyang, Yang Yu, Jiachang Wang, and Cuicui Ji. 2026. "Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010366

APA StyleDu, M., Yu, Y., Wang, J., & Ji, C. (2026). Autophagy–Lysosome Pathway Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010366