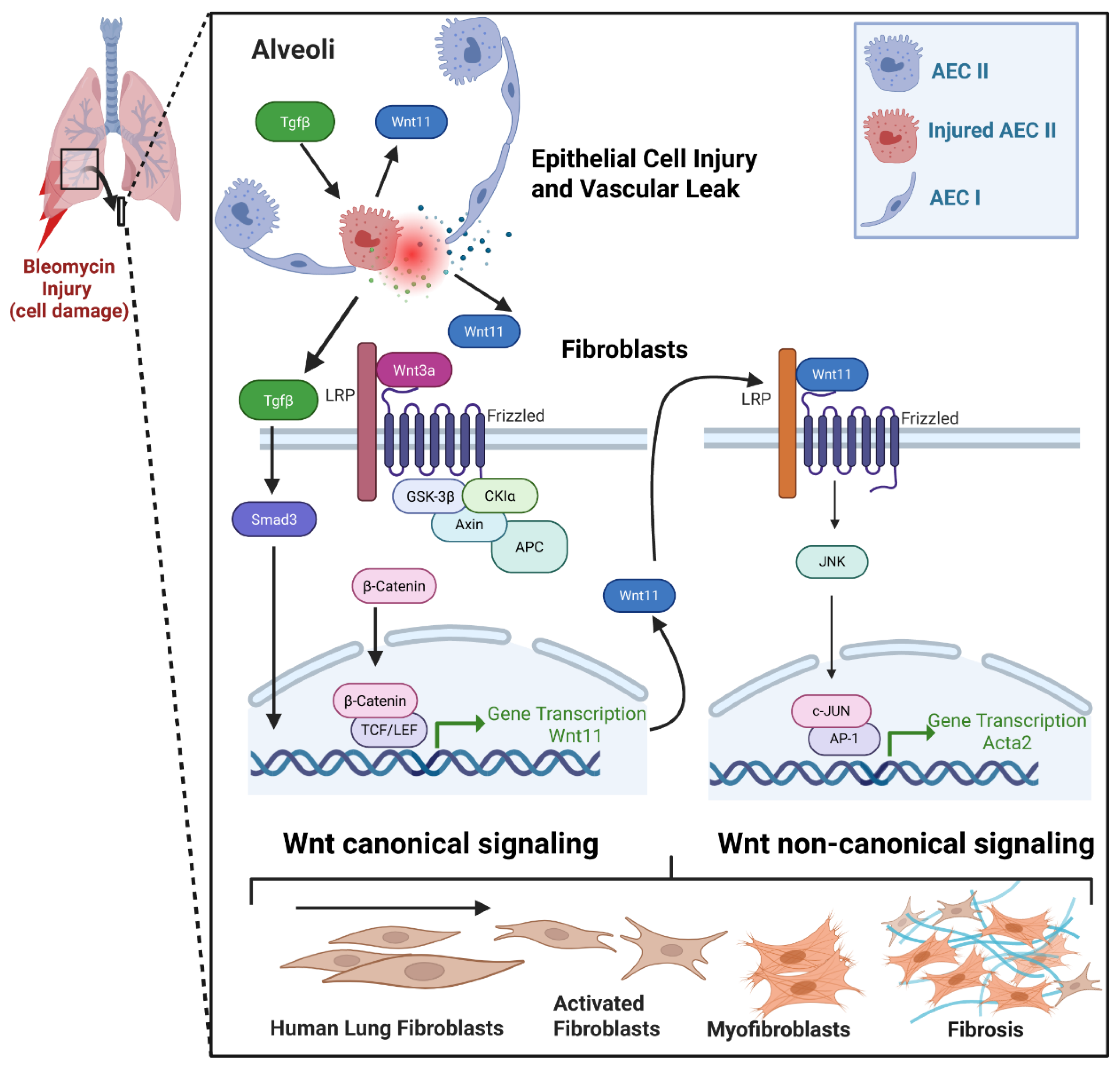

Non-Canonical Wnt11 Signaling Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis via Fibroblast and Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Crosstalk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

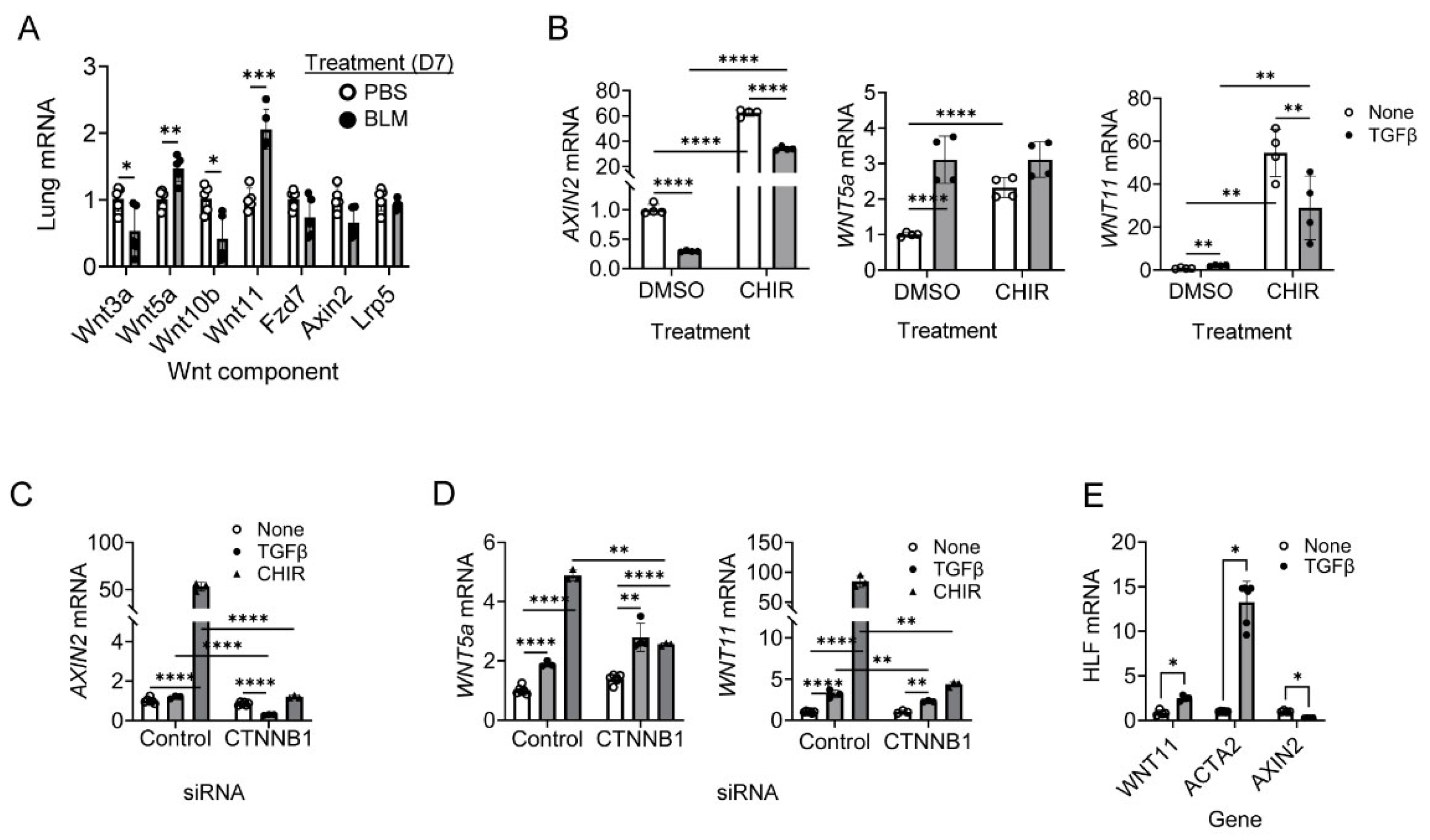

2.1. Wnt11 Induction Is Dependent on β-Catenin in Human Lung Fibroblasts (HLF)

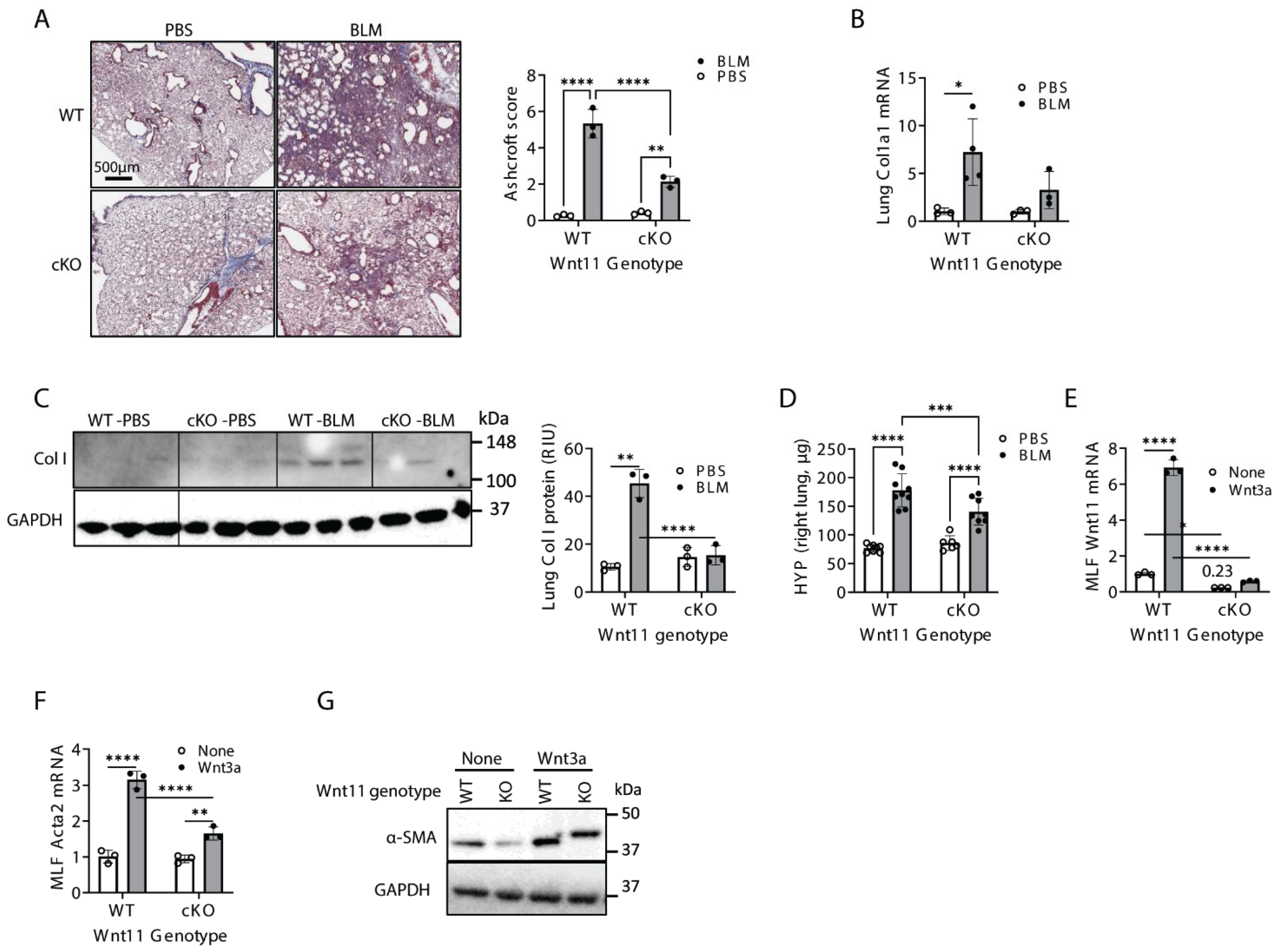

2.2. Mesenchymal Cell-Specific Wnt11 Deficiency In Vivo Impairs Pulmonary Fibrosis and Myofibroblast Differentiation

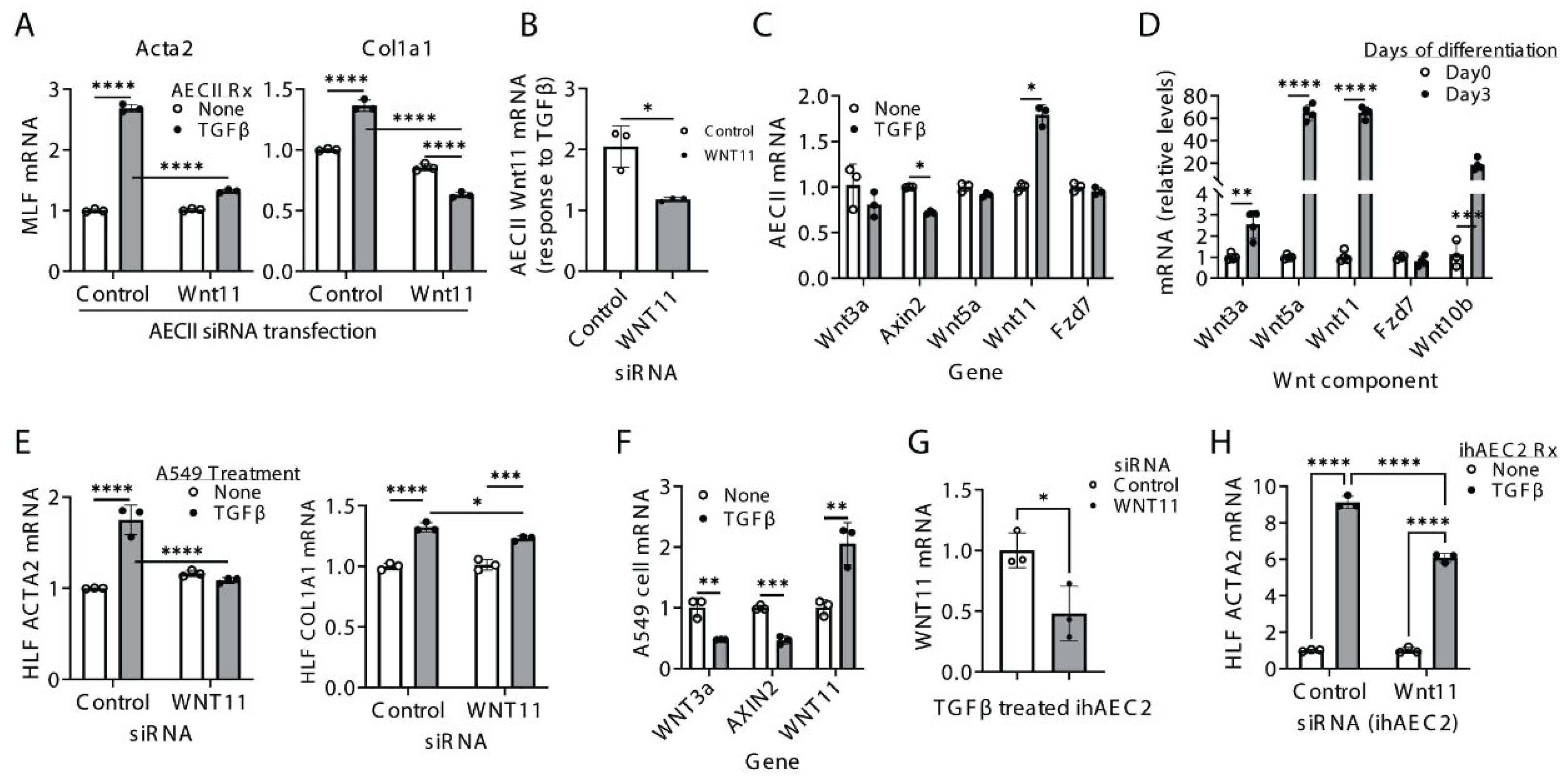

2.3. Non-Canonical Wnt11 Promotes Myofibroblast Differentiation via a Paracrine Mechanism>

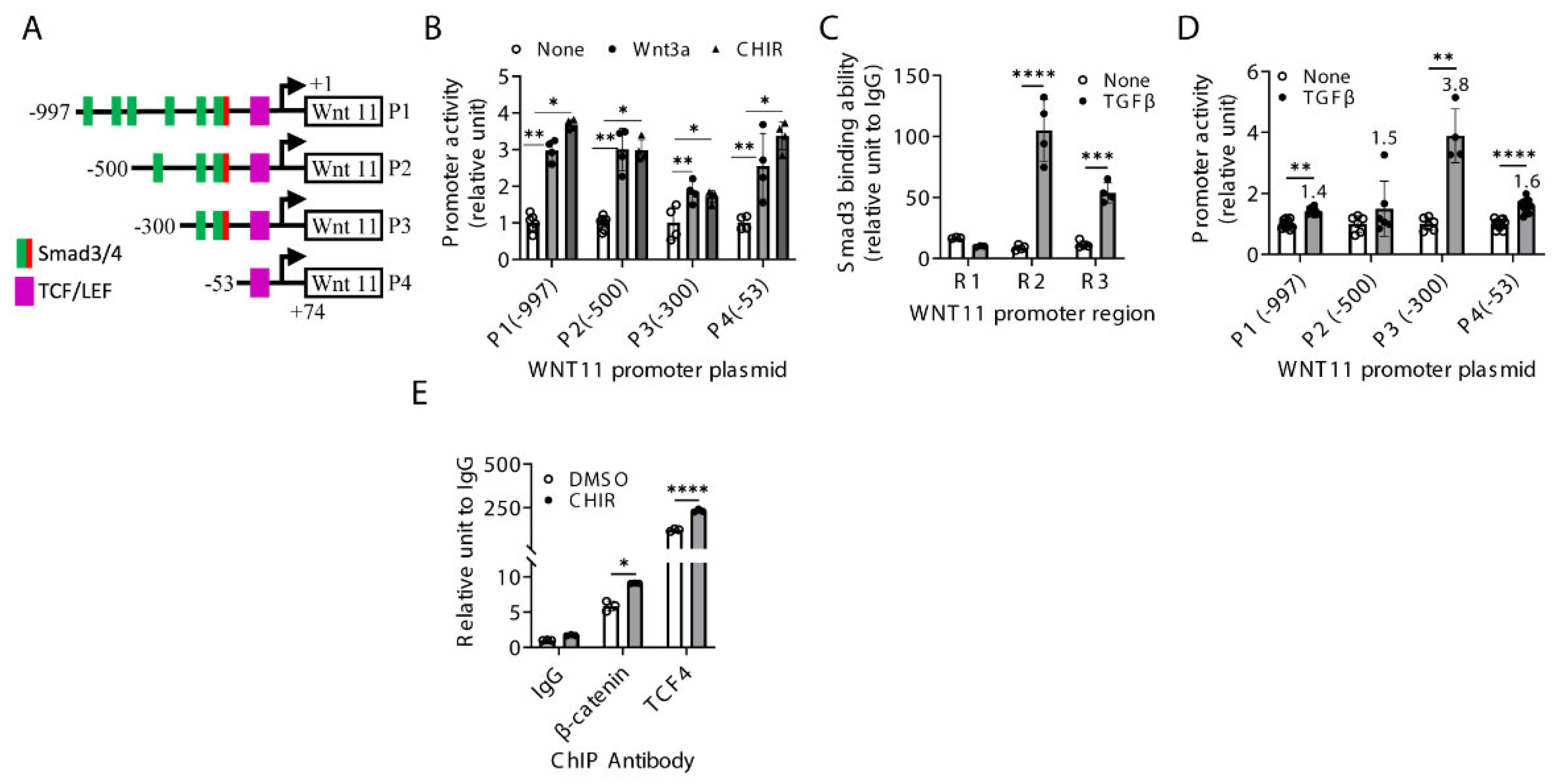

2.4. Regulation of Wnt11 Transcription and Expression

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Mice and BLM Model of Pulmonary Fibrosis

4.2. Cell Isolations and Treatments

4.3. siRNA Transfection and Adenoviral Transduction

4.4. Real Time PCR and Western Blotting Analysis

4.5. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

4.6. Promoter Activity Assay

4.7. Histological Staining and Ashcroft Scoring

4.8. Statistics

4.9. Study Approval

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinz, B.; Phan, S.H.; Thannickal, V.J.; Prunotto, M.; Desmouliere, A.; Varga, J.; De Wever, O.; Mareel, M.; Gabbiani, G. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: Paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, S.H. Genesis of the myofibroblast in lung injury and fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2012, 9, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, T.; Rindtorff, N.; Boutros, M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, W.J.; Bothwell, A.L.M. Canonical and Non-Canonical Wnt Signaling in Immune Cells. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, C.Y.; Nusse, R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 20, 781–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Gonzalez De Los Santos, F.; Hirsch, M.; Wu, Z.; Phan, S.H. Noncanonical Wnt Signaling Promotes Myofibroblast Differentiation in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 65, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.R.; Sills, W.S.; Hanrahan, K.; Ziegler, A.; Tidd, K.M.; Cook, E.; Sannes, P.L. Expression of WNT5A in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Its Control by TGF-beta and WNT7B in Human Lung Fibroblasts. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2016, 64, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Cai, Y.; Soofi, A.; Dressler, G.R. Activation of Wnt11 by transforming growth factor-beta drives mesenchymal gene expression through non-canonical Wnt protein signaling in renal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 21290–21302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bellusci, S.; Borok, Z.; Minoo, P. Non-canonical WNT signalling in the lung. J. Biochem. 2015, 158, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, M.P.; Dawn, B. Noncanonical Wnt11 signaling and cardiomyogenic differentiation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 18, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, M.P.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Li, Q.; Hunt, G.; Ranjan, S.; Ou, Q.; Tang, X.L.; Johnson, R.K.; Bolli, R.; Dawn, B. Noncanonical Wnt11 signaling is sufficient to induce cardiomyogenic differentiation in unfractionated bone marrow mononuclear cells. Circulation 2008, 117, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Liang, J.; Huang, K.; Liu, X.; Taghavifar, F.; Yao, C.; Parimon, T.; Liu, N.; Dai, K.; Aziz, A.; et al. Basal Cell-derived WNT7A Promotes Fibrogenesis at the Fibrotic Niche in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 68, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisson, J.A.; Mills, B.; Paul Helt, J.C.; Zwaka, T.P.; Cohen, E.D. Wnt5a and Wnt11 inhibit the canonical Wnt pathway and promote cardiac progenitor development via the Caspase-dependent degradation of AKT. Dev. Biol. 2015, 398, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.D.; Miller, M.F.; Wang, Z.; Moon, R.T.; Morrisey, E.E. Wnt5a and Wnt11 are essential for second heart field progenitor development. Development 2012, 139, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; DeRan, M.T.; Ignatius, M.S.; Grandinetti, K.B.; Clagg, R.; McCarthy, K.M.; Lobbardi, R.M.; Brockmann, J.; Keller, C.; Wu, X.; et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors induce the canonical WNT/beta-catenin pathway to suppress growth and self-renewal in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5349–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ting, C.; Riemondy, K.A.; Douglas, M.; Foster, K.; Patel, N.; Kaku, N.; Linsalata, A.; Nemzek, J.; Varisco, B.M.; et al. Regulation of epithelial transitional states in murine and human pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e165612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Morley, M.; Hawkins, F.; McCauley, K.B.; Jean, J.C.; Heins, H.; Na, C.L.; Weaver, T.E.; Vedaie, M.; Hurley, K.; et al. Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells into Functional Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 472–488.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumduri, C.; Gurumurthy, R.K.; Berger, H.; Dietrich, O.; Kumar, N.; Koster, S.; Brinkmann, V.; Hoffmann, K.; Drabkina, M.; Arampatzi, P.; et al. Opposing Wnt signals regulate cervical squamocolumnar homeostasis and emergence of metaplasia. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetshina, A.; Palumbo, K.; Dees, C.; Bergmann, C.; Venalis, P.; Zerr, P.; Horn, A.; Kireva, T.; Beyer, C.; Zwerina, J.; et al. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-beta-mediated fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilosi, M.; Poletti, V.; Zamo, A.; Lestani, M.; Montagna, L.; Piccoli, P.; Pedron, S.; Bertaso, M.; Scarpa, A.; Murer, B.; et al. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 162, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flozak, A.S.; Lam, A.P.; Russell, S.; Jain, M.; Peled, O.N.; Sheppard, K.A.; Beri, R.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.; Gottardi, C.J. Beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling is activated during lung injury and promotes the survival and migration of alveolar epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 3157–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, W.R.; Chi, E.Y., Jr.; Ye, X.; Nguyen, C.; Tien, Y.T.; Zhou, B.; Borok, Z.; Knight, D.A.; Kahn, M. Inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin/CREB binding protein (CBP) signaling reverses pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14309–14314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konigshoff, M.; Kramer, M.; Balsara, N.; Wilhelm, J.; Amarie, O.V.; Jahn, A.; Rose, F.; Fink, L.; Seeger, W.; Schaefer, L.; et al. WNT1-inducible signaling protein-1 mediates pulmonary fibrosis in mice and is upregulated in humans with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carthy, J.M.; Garmaroudi, F.S.; Luo, Z.; McManus, B.M. Wnt3a induces myofibroblast differentiation by upregulating TGF-beta signaling through SMAD2 in a beta-catenin-dependent manner. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, S.; He, W.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Hou, Y.; Nie, J.; Hou, F.F.; Kahn, M.; Liu, Y. Targeted inhibition of beta-catenin/CBP signaling ameliorates renal interstitial fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1642–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, J.; Zhu, X.; Tang, C.; Hu, D. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway forms a negative feedback loop during TGF-beta1 induced human normal skin fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012, 65, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa-Vergniory, N.; Gorrono-Etxebarria, I.; Gonzalez-Salazar, I.; Kypta, R.M. A switch from canonical to noncanonical Wnt signaling mediates early differentiation of human neural stem cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 3196–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, M.C.; Nattamai, K.J.; Dorr, K.; Marka, G.; Uberle, B.; Vas, V.; Eckl, C.; Andra, I.; Schiemann, M.; Oostendorp, R.A.; et al. A canonical to non-canonical Wnt signalling switch in haematopoietic stem-cell ageing. Nature 2013, 503, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakisaka, Y.; Tsuchiya, M.; Nakamura, T.; Tamura, M.; Shimauchi, H.; Nemoto, E. Wnt5a attenuates Wnt3a-induced alkaline phosphatase expression in dental follicle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 336, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, P.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.; Wu, D. Multiple mechanisms for Wnt11-mediated repression of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24659–24665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T.; Fujita, Y.; Araya, J.; Watanabe, N.; Fujimoto, S.; Kawamoto, H.; Minagawa, S.; Hara, H.; Ohtsuka, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Human bronchial epithelial cell-derived extracellular vesicle therapy for pulmonary fibrosis via inhibition of TGF-beta-WNT crosstalk. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; Kahn, M.; Ann, D.K.; Han, A.; Wang, H.; Nguyen, C.; Flodby, P.; Zhong, Q.; Krishnaveni, M.S.; et al. Interactions between beta-catenin and transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathways mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition and are dependent on the transcriptional co-activator cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP). J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 7026–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Flanders, K.C.; Phan, S.H. Cellular localization of transforming growth factor-beta expression in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 147, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gauldie, J.; Bonniaud, P.; Sime, P.; Ask, K.; Kolb, M. TGF-beta, Smad3 and the process of progressive fibrosis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wu, Z.; Phan, S.H. Smad3 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 29, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Phan, S.H. Inhibition of myofibroblast apoptosis by transforming growth factor beta(1). Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999, 21, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbe, E.; Letamendia, A.; Attisano, L. Association of Smads with lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1/T cell-specific factor mediates cooperative signaling by the transforming growth factor-beta and wnt pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8358–8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yu, H.; Ding, L.; Wu, Z.; Gonzalez De Los Santos, F.; Liu, J.; Ullenbruch, M.; Hu, B.; Martins, V.; Phan, S.H. Conditional Knockout of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase in Mesenchymal Cells Impairs Mouse Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaux, F.; Liu, T.; McGarry, B.; Ullenbruch, M.; Xing, Z.; Phan, S.H. Eosinophils and T lymphocytes possess distinct roles in bleomycin-induced lung injury and fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 5470–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Gonzalez De Los Santos, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Rinke, A.E.; Kim, K.K.; Phan, S.H. Telomerase reverse transcriptase ameliorates lung fibrosis by protecting alveolar epithelial cells against senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 8861–8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Vedaie, M.; Roberts, D.A.; Thomas, D.C.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Alysandratos, K.D.; Hawkins, F.; Kotton, D.N. Derivation of self-renewing lung alveolar epithelial type II cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 3303–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, E.; Ahn, S.S.; Yeo, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Seo, J.K.; Lee, Y.H.; Shin, S.Y. WNT11 is a direct target of early growth response protein 1. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, T.; Simpson, J.M.; Timbrell, V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J. Clin. Pathol. 1988, 41, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gonzalez De Los Santos, F.; Ando, A.; Hu, B.; Rosek, A.; Phan, S.H.; Liu, T. Non-Canonical Wnt11 Signaling Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis via Fibroblast and Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Crosstalk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010351

Gonzalez De Los Santos F, Ando A, Hu B, Rosek A, Phan SH, Liu T. Non-Canonical Wnt11 Signaling Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis via Fibroblast and Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Crosstalk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010351

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez De Los Santos, Francina, Akira Ando, Biao Hu, Alyssa Rosek, Sem H. Phan, and Tianju Liu. 2026. "Non-Canonical Wnt11 Signaling Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis via Fibroblast and Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Crosstalk" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010351

APA StyleGonzalez De Los Santos, F., Ando, A., Hu, B., Rosek, A., Phan, S. H., & Liu, T. (2026). Non-Canonical Wnt11 Signaling Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis via Fibroblast and Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cell Crosstalk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010351