AHR Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Cholesterol Accumulation via Inhibiting Bile Acid Synthesis in MAFLD Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

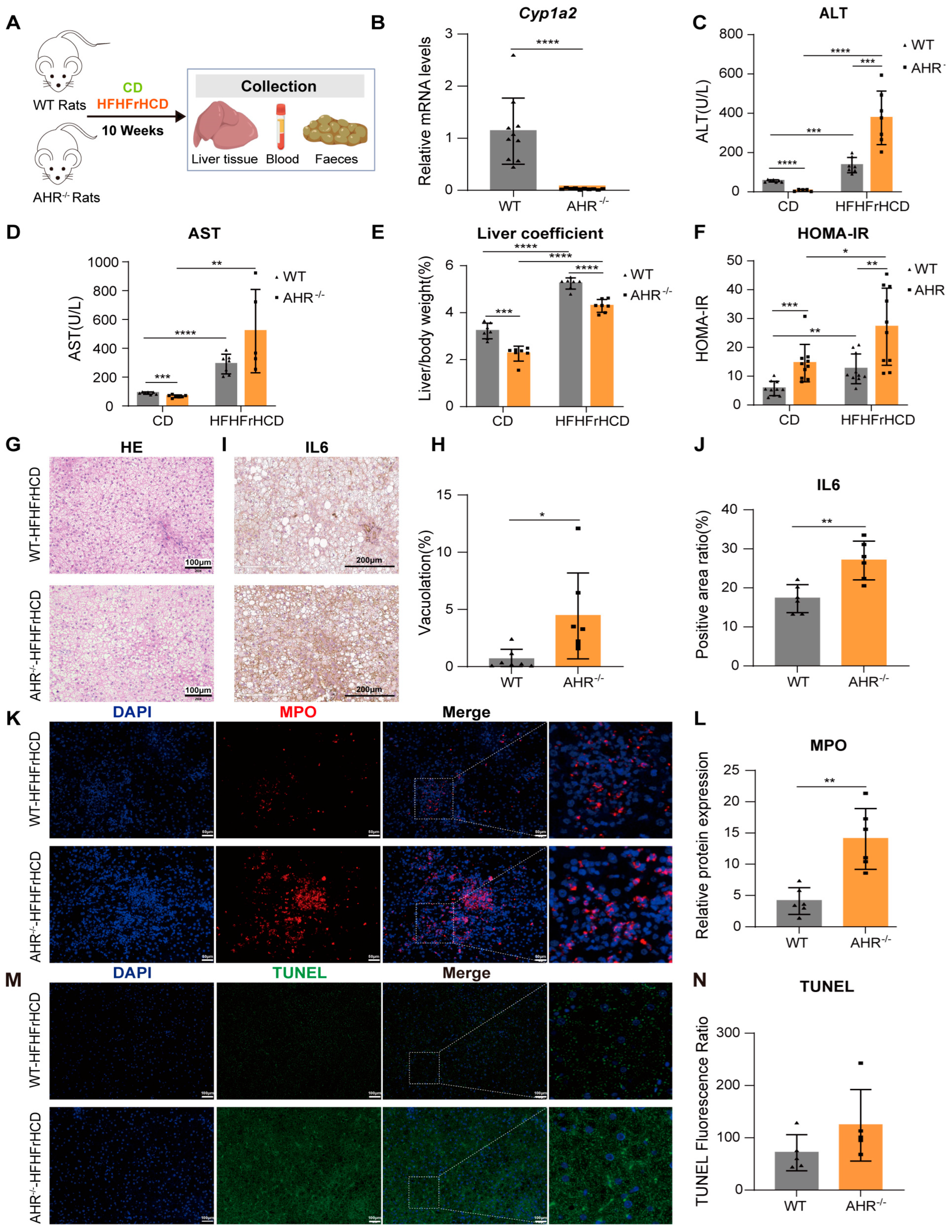

2.1. AHR Knockout Exacerbates HFHFrHCD-Induced Liver Injury and Insulin Resistance

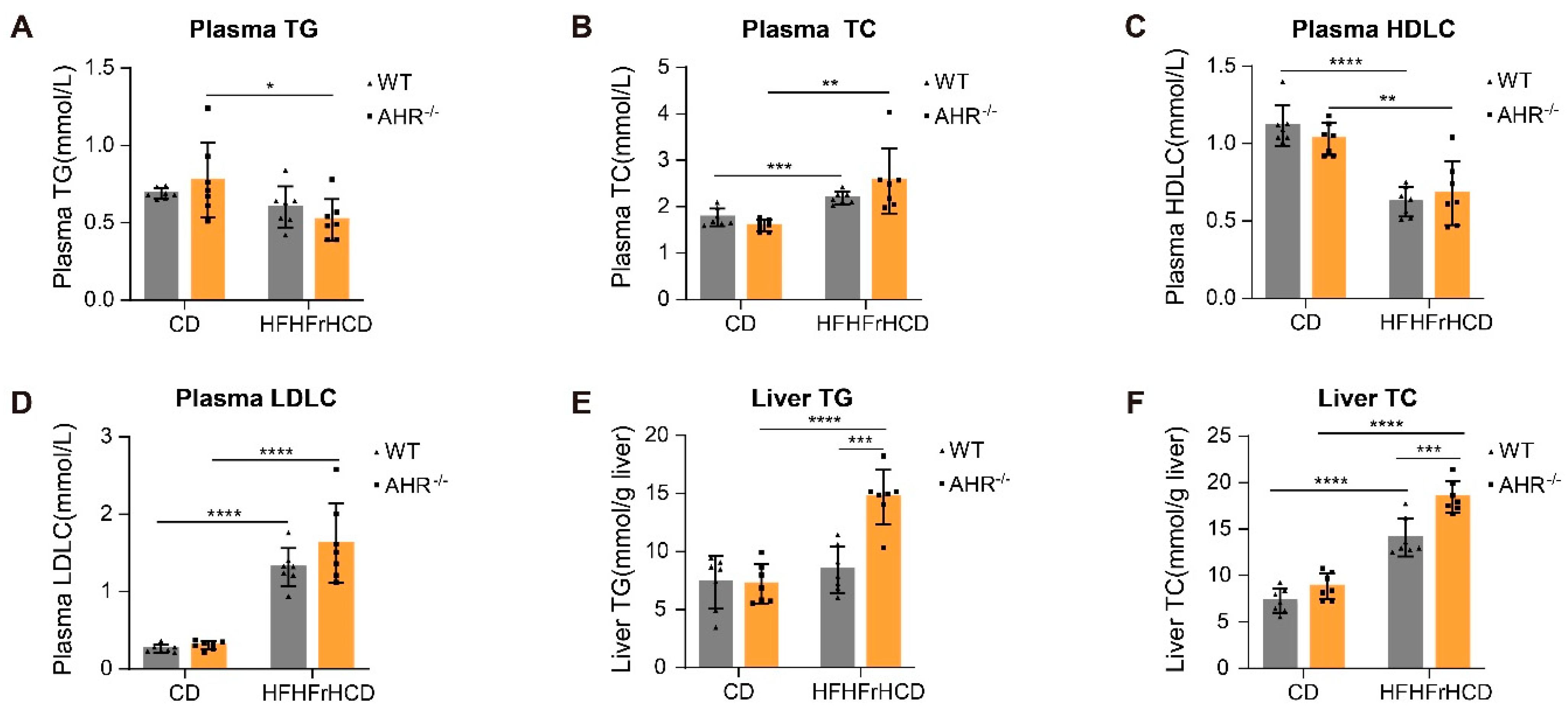

2.2. AHR Knockout Facilitates HFHFrHCD-Induced Lipid Accumulation

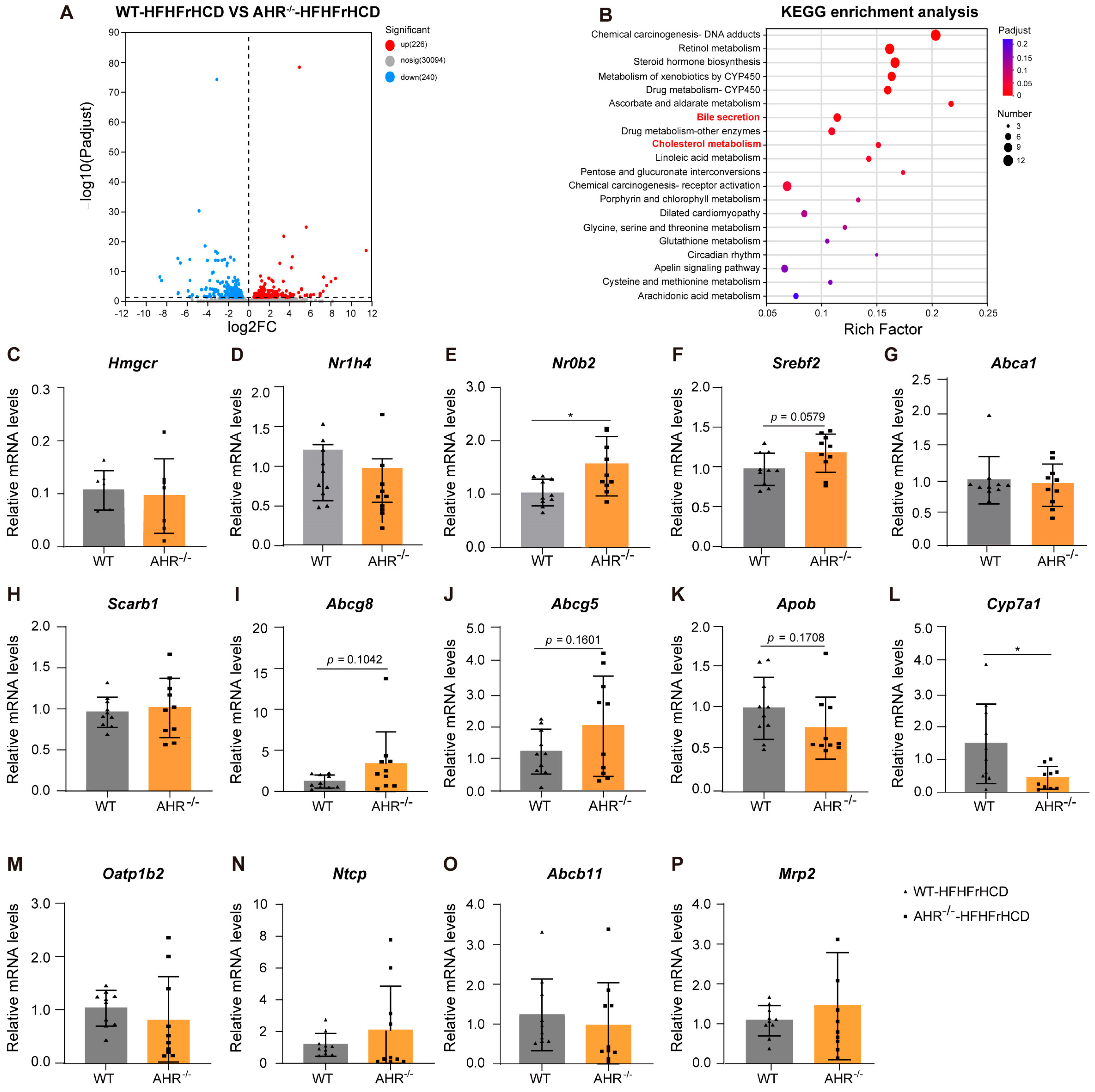

2.3. Expression of Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes Dysregulated in AHR Knockout Rats Under the Pressure of HFHFrHCD

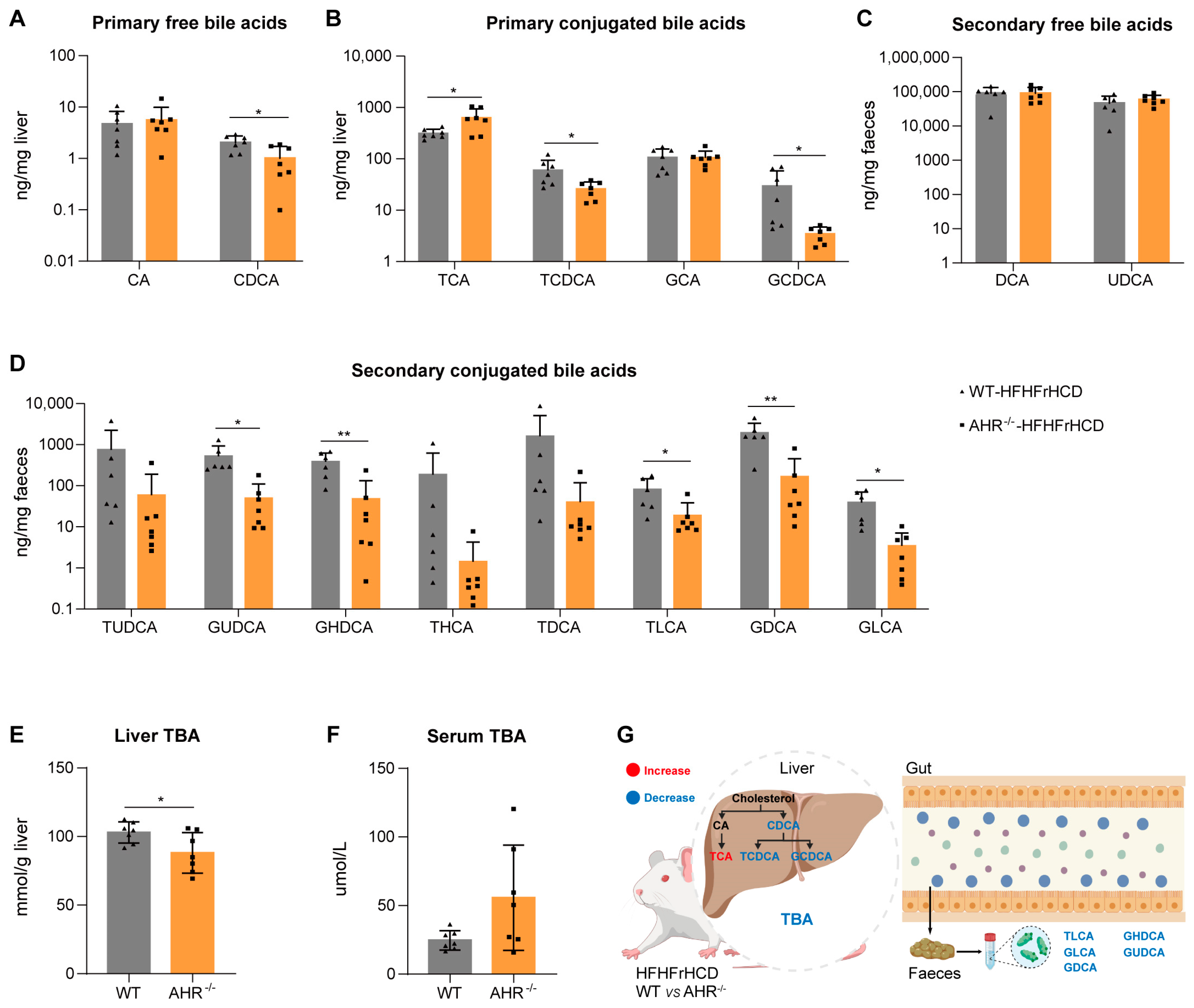

2.4. Effect of AHR Deficiency on Hepatic and Fecal Bile Acid Profiles in MAFLD Rats

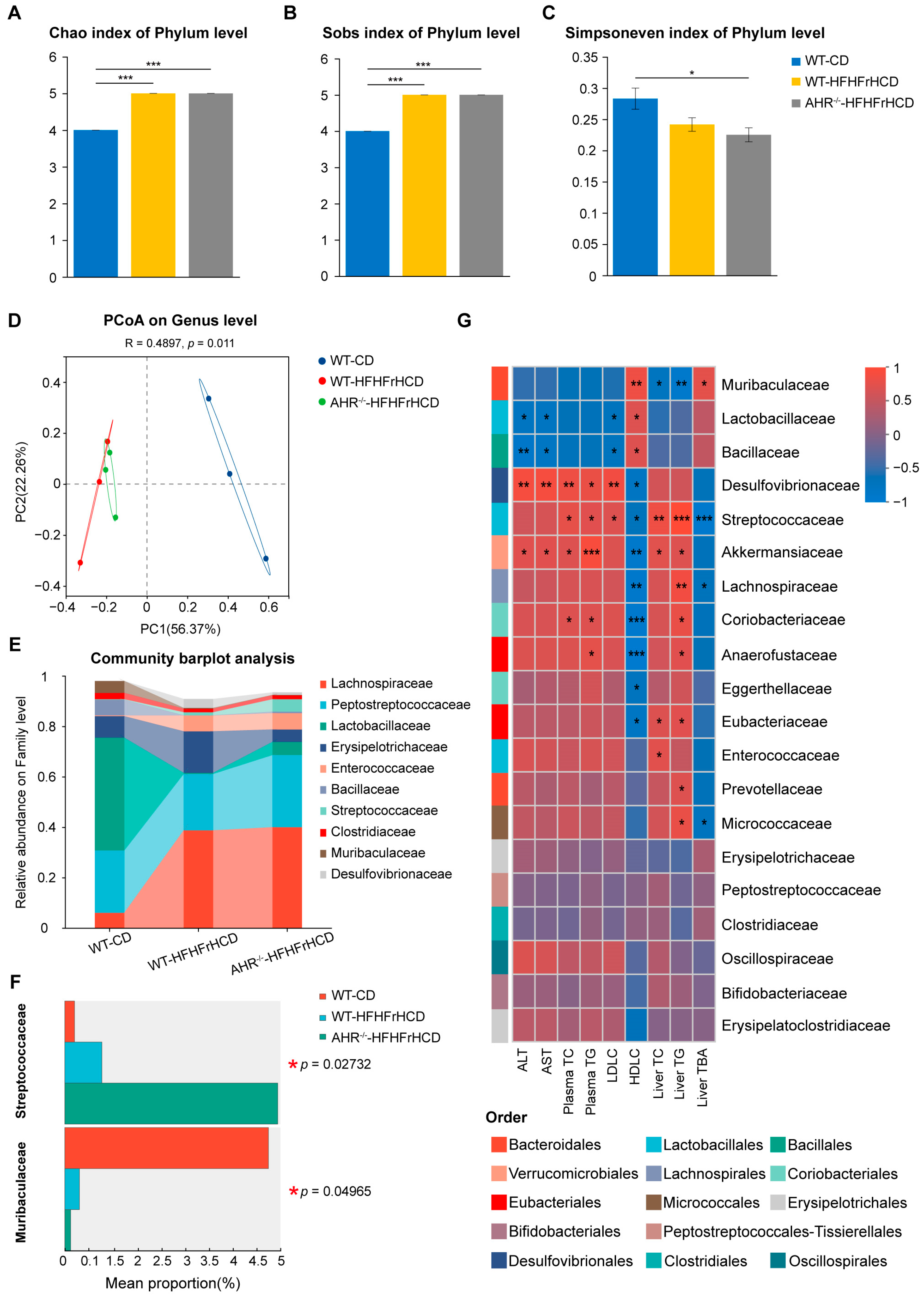

2.5. Effect of AHR Deficiency on Gut Microbiota Diversity and Composition in MAFLD Rats

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Experiments

4.2. Biochemical Assays

4.3. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

4.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.5. Apoptosis Staining

4.6. Immunohistochemical Staining

4.7. Detection and Analysis of Intestinal Bile Acids-LC-MS/MS Analysis

4.8. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) and Bioinformatic Analysis

4.9. RT-qPCR

4.10. Analysis of Gut Microbial Diversity

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| CA | Cholic acid |

| CD | Control diet |

| CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic Acid |

| DCA | Deoxycholic Acid |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| GCA | Glycocholic Acid |

| GCDCA | Glycochenodeoxycholic Acid |

| GDCA | Glycodeoxycholic Acid |

| GHDCA | Glycohyodeoxycholic Acid |

| GLCA | Glycolithocholic Acid |

| GUDCA | Glycoursodeoxycholic Acid |

| HDLC | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HFHFrHCD | High-fat, high-fructose, high-cholesterol diet |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| LCA | Lithocholic Acid |

| LDLC | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| SD | Sprague-Dawley |

| TBA | Total bile acid |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TCA | Taurocholic Acid |

| TCDCA | Taurochenodeoxycholic Acid |

| TDCA | Taurodeoxycholic Acid |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| THCA | Taurohyodeoxycholic acid |

| TLCA | Taurolithocholic Acid |

| TUDCA | Tauroursodeoxycholic acid |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic Acid |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Dufour, J.-F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Le, M.H.; Cheung, R.C.; Nguyen, M.H. Differential Clinical Characteristics and Mortality Outcomes in Persons With NAFLD and/or MAFLD. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, X.; Tian, T.; Ding, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Guo, W.; Jiang, L.; et al. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of MAFLD and NAFLD in Chinese Health Examination Populations. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayada, I.; van Kleef, L.A.; Alferink, L.J.M.; Li, P.; de Knegt, R.J.; Pan, Q. Systematically comparing epidemiological and clinical features of MAFLD and NAFLD by meta-analysis: Focusing on the non-overlap groups. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, J.; Takashimizu, S.; Suzuki, N.; Ohshinden, K.; Sawamoto, K.; Mishima, Y.; Tsuruya, K.; Arase, Y.; Yamano, M.; Kishimoto, N.; et al. Comparative study of MAFLD as a predictor of metabolic disease treatment for NAFLD. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ayada, I.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wen, T.; Ma, Z.; Bruno, M.J.; de Knegt, R.J.; Cao, W.; et al. Estimating Global Prevalence of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight or Obese Adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e573–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, O.O.; Hillhouse, S.A.; Anderson, C.D.; Hinds, T.D.; Stec, D.E. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): Functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 1347–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, D.Y.; van de Sluis, B. Function of the endolysosomal network in cholesterol homeostasis and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ai, Y.; Hu, C.; Bawa, F.N.C.; Xu, Y. Transcription factors, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, and therapeutic implications. Genes. Dis. 2025, 12, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Tung, H.-C.; Li, S.; Niu, Y.; Garbacz, W.G.; Lu, P.; Bi, Y.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Xu, M.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling Prevents Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Liver Fibrogenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrzosek, L.; Ciocan, D.; Hugot, C.; Spatz, M.; Dupeux, M.; Houron, C.; Moal, V.L.-L.; Puchois, V.; Ferrere, G.; Trainel, N.; et al. Microbiota tryptophan metabolism induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation and improves alcohol-induced liver injury. Gut 2021, 70, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Jiang, S.; Yin, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Yin, B.C.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Qi, N.; Zhou, Y.; et al. The microbiota-dependent tryptophan metabolite alleviates high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance through the hepatic AhR/TSC2/mTORC1 axis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2400385121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, K.W. Modulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and the NAD(+)-consuming enzyme CD38: Searches of therapeutic options for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 175, 113905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sundaram, K.; Mu, J.; Dryden, G.W.; Sriwastva, M.K.; Lei, C.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, X.; Xu, F.; Yan, J.; et al. High-fat diet-induced upregulation of exosomal phosphatidylcholine contributes to insulin resistance. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.J.; Suh, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Poulsen, K.L.; An, Y.A.; Moorthy, B.; Hartig, S.M.; Moore, D.D.; Kim, K.H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor maintains hepatic mitochondrial homeostasis in mice. Mol. Metab. 2023, 72, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graelmann, F.J.; Gondorf, F.; Majlesain, Y.; Niemann, B.; Klepac, K.; Gosejacob, D.; Gottschalk, M.; Mayer, M.; Iriady, I.; Hatzfeld, P.; et al. Differential cell type-specific function of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its repressor in diet-induced obesity and fibrosis. Mol. Metab. 2024, 85, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Yu, J.; Zhai, J.; et al. L-Kynurenine activates the AHR-PCSK9 pathway to mediate the lipid metabolic and ovarian dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism 2025, 168, 156238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tian, R.; Liang, C.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xie, Q.; Huang, F.; Yuan, H. Biomimetic nanoplatform with microbiome modulation and antioxidant functions ameliorating insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction for T2DM management. Biomaterials 2025, 313, 122804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wahlang, B.; Thapa, M.; Head, K.Z.; Hardesty, J.E.; Srivastava, S.; Merchant, M.L.; Rai, S.N.; Prough, R.A.; Cave, M.C. Proteomics and metabolic phenotyping define principal roles for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mouse liver. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3806–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, M.; Krishnan, A.; Viker, K.; Sanderson, S.; Cazanave, S.; McConico, A.; Masuoko, H.; Gores, G. Fast food diet mouse: Novel small animal model of NASH with ballooning, progressive fibrosis, and high physiological fidelity to the human condition. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G825–G834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Lee, Y.A.; Fujiwara, N.; Ybanez, M.; Allen, B.; Martins, S.; Fiel, M.I.; Goossens, N.; Chou, H.I.; Hoshida, Y.; et al. A simple diet- and chemical-induced murine NASH model with rapid progression of steatohepatitis, fibrosis and liver cancer. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 385–395, Erratum in J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Guzmán, J.E.; Belmont-Hernández, R.A.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C.; Uribe, M.; Nuño-Lámbarri, N. Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeier, R.; van der Vorst, E.P.C. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NRF2): An important crosstalk in the gut-liver axis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 233, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Debelius, J.; Brenner, D.A.; Karin, M.; Loomba, R.; Schnabl, B.; Knight, R. The gut–liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 397–411, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.M.; Jaeger, C.D.; Krager, S.L.; Bottum, K.M.; Liu, J.; Liao, D.F.; Tischkau, S.A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor deficiency protects mice from diet-induced adiposity and metabolic disorders through increased energy expenditure. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Marín, N.; Merino, J.M.; Alvarez-Barrientos, A.; Patel, D.P.; Takahashi, S.; González-Sancho, J.M.; Gandolfo, P.; Rios, R.M.; Muñoz, A.; Gonzalez, F.J.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Promotes Liver Polyploidization and Inhibits PI3K, ERK, and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. IScience 2018, 4, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Zhang, H.; Lund, H.; Zhang, Z.; Castleberry, M.; Rodriguez, M. Intracellular tPA-PAI-1 interaction determines VLDL assembly in hepatocytes. Science 2023, 381, Eadh5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Rimal, B.; Jiang, C.; Chiang, J.Y.L.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 237, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid signaling in metabolic disease and drug therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 948–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopyk, D.M.; Grakoui, A. Contribution of the Intestinal Microbiome and Gut Barrier to Hepatic Disorders. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ye, J.; Shao, C.; Zhong, B. Compositional alterations of gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zheng, R.-D.; Sun, X.-Q.; Ding, W.-J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fan, J.-G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2017, 16, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Peng, S.; Cheng, J.; Yang, H.; Lin, L.; Yang, G.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wen, Z. Chitosan-Stabilized Selenium Nanoparticles Alleviate High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) by Modulating the Gut Barrier Function and Microbiota. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment Restores Gut Microbiota and Alleviates Liver Inflammation in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitic Mouse Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 788558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Huang, F.; Shen, G.X. Dose-Responses Relationship in Glucose Lowering and Gut Dysbiosis to Saskatoon Berry Powder Supplementation in High Fat-High Sucrose Diet-Induced Insulin Resistant Mice. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Tan, M.; Chen, X. Punicic acid ameliorates obesity and liver steatosis by regulating gut microbiota composition in mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7897–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lui, E.M.K.; Xiao, M. Pu-erh tea ameliorates obesity and modulates gut microbiota in high fat diet fed mice. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, T.; Suruga, K.; Oshima, Y.; Fukiharu, M.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Goda, T. Dietary acetic acid reduces serum cholesterol and triacylglycerols in rats fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, H.; Haga, S.; Aoyama, Y.; Kiriyama, S. Short-chain fatty acids suppress cholesterol synthesis in rat liver and intestine. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Qu, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Ren, F.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Ge, S.; Wu, C.; et al. SCFAs alleviated steatosis and inflammation in mice with NASH induced by MCD. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 245, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cyp1a2 | Forward | AAGAGCGAGGAGATGCTCAA |

| Reverse | TGCCGATCTCTGCCAATCAC | |

| Abcg8 | Forward | GATGCTGGCTATCATAGGGAGC |

| Reverse | TCTCTGCCTGTGATAACGTCGA | |

| Apob | Forward | AGAGGATCCCTGAGCAGGCTTCCTCAGCAG |

| Reverse | TTAAAGCTTCAATGATTCTATCAATAATCTG | |

| Oatp1b2 | Forward | ACTACAAGTCAGCGGCTTCA |

| Reverse | GGGTTCATTTTGGCGATTCC | |

| Abcb11 | Forward | AGCCAAAAGCTGAAAAGGTTGT |

| Reverse | CTGGGCCATTCCATGTAGCA | |

| Angptl3 | Forward | TGACACCCAATCAGGCACTC |

| Reverse | AGTGAGTGATGCAAGGAAATCAC | |

| Angptl4 | Forward | TTCTCTACCTGGGACCAAGA |

| Reverse | CTGTAGTGGATAGTAGCGGC | |

| Adcy1 | Forward | TCACCCAGCCCAAGACGGATC |

| Reverse | TCAGTAGCCTCAGCCACGGATG | |

| Ugt2b | Forward | ATTTTGTCGGGACTGGCTGG |

| Reverse | TGGTGGGCCTTCCCAAAATC | |

| Ugt2a1 | Forward | CCCTTGCCCAGATTCCTCAG |

| Reverse | CTCTGGTTTTGGGATGTCCAAG | |

| Ugt2b7 | Forward | GCCCATCCTTGCCAAACATT |

| Reverse | GTGCAAAGTCTTCCATTTCCTTA | |

| Hmgcr | Forward | CCTCCATTGAGATCCGGAGG |

| Reverse | GATGCACCGGGTTATCGTGA | |

| Srebf2 | Forward | TGCCTCACTCTCTGGAAAGG |

| Reverse | GTAGGCCGCTGACATTGAG | |

| Abca1 | Forward | GGGTGGCTTCGCCTACTTG |

| Reverse | GACGCCCGTTTTCTTCTCAG | |

| Scarb1 | Forward | GCATTCGGAACAGTGCAACA |

| Reverse | TCATGAATGGTGCCCACATC | |

| Abcg5 | Forward | CGCAGGAACCGCATTGAAA |

| Reverse | TGTCGAAGTGGTGGAAGAGCT | |

| Ntcp | Forward | CATCGTGATGACCACCTGCT |

| Reverse | TGGACTTGAGGACGATCCCT | |

| Mrp2 | Forward | TGCCCATTATCCGTGCCTTT |

| Reverse | GAACAAAGCCCACAACGTCC | |

| β-actin | Forward | CAGCTGAGAGGGAAATCGTG |

| Reverse | CGTTGCCAATAGTGATGACC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; He, H.; Hu, D.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Tian, Y.; Gong, L. AHR Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Cholesterol Accumulation via Inhibiting Bile Acid Synthesis in MAFLD Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010349

Xu J, Liu P, Wu Y, He H, Hu D, Sun J, Chen J, Tian Y, Gong L. AHR Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Cholesterol Accumulation via Inhibiting Bile Acid Synthesis in MAFLD Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010349

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Junjiu, Pengwei Liu, Yuling Wu, Hongxiu He, Dandan Hu, Jianhua Sun, Jing Chen, Ying Tian, and Likun Gong. 2026. "AHR Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Cholesterol Accumulation via Inhibiting Bile Acid Synthesis in MAFLD Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010349

APA StyleXu, J., Liu, P., Wu, Y., He, H., Hu, D., Sun, J., Chen, J., Tian, Y., & Gong, L. (2026). AHR Deficiency Exacerbates Hepatic Cholesterol Accumulation via Inhibiting Bile Acid Synthesis in MAFLD Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010349