3D Bioprinting Strategies in Autoimmune Disease Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

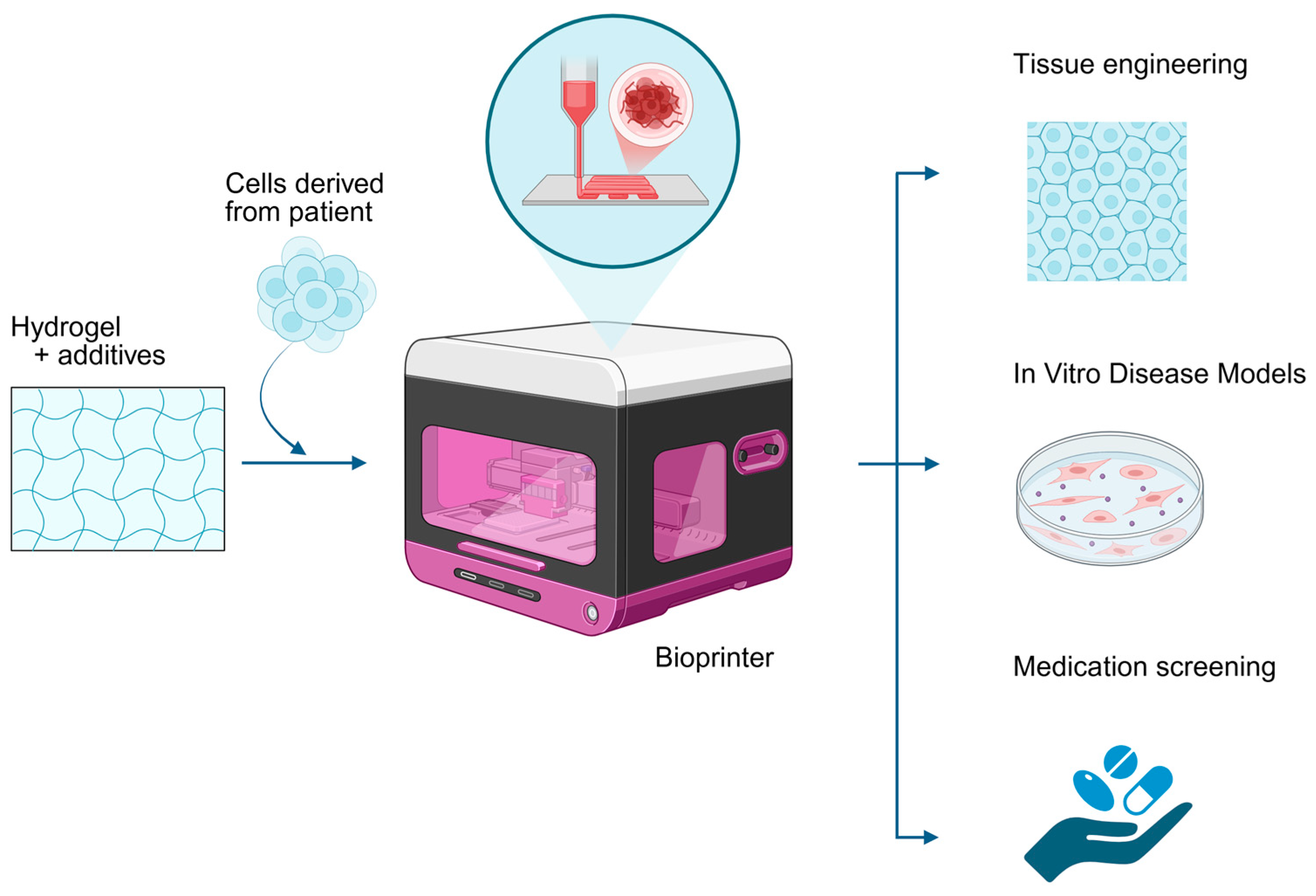

2. 3D Bioprinting for Autoimmune Disease Modeling

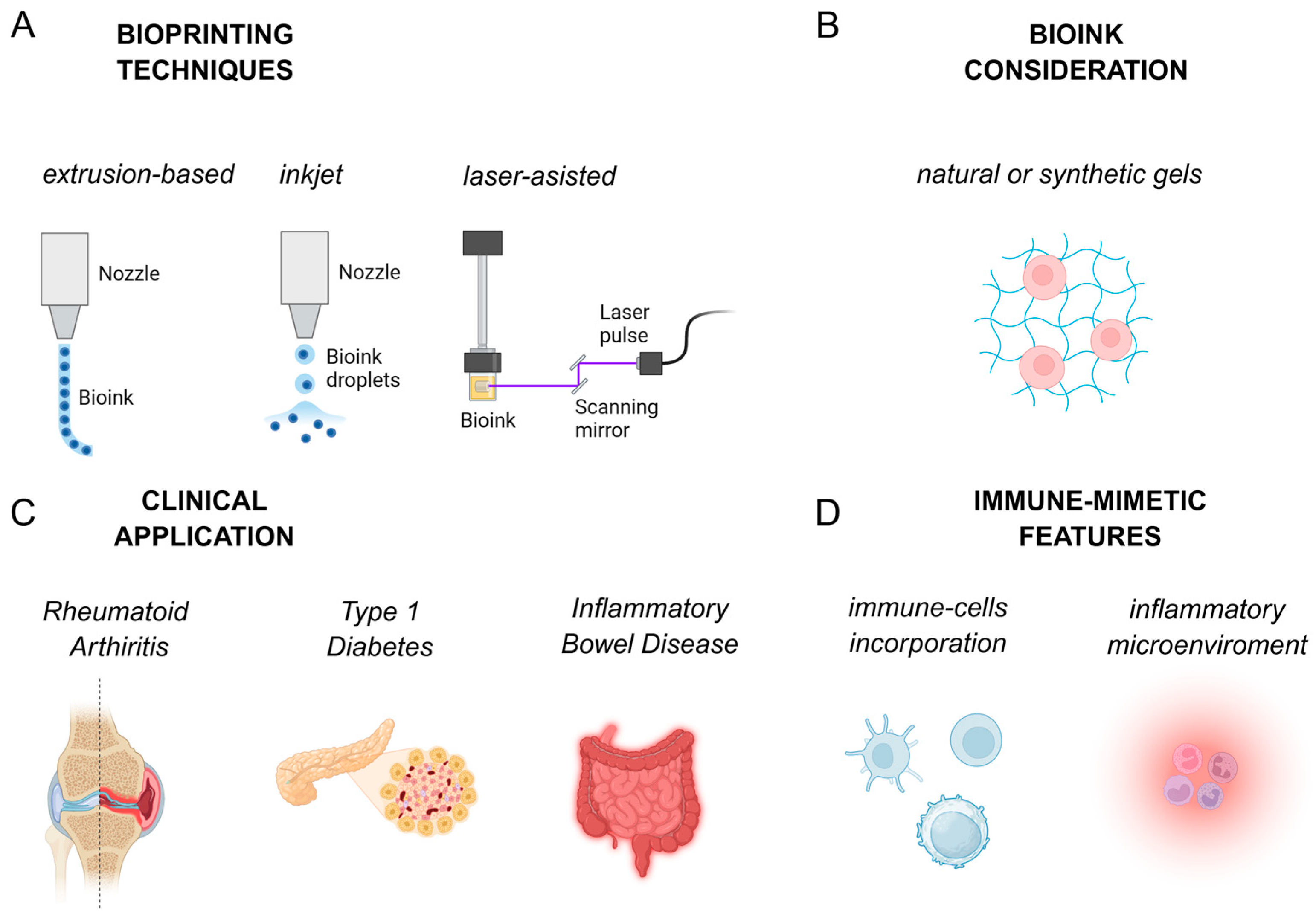

2.1. Bioprinting Techniques

2.2. Bioink

2.3. Application of 3D Bioprinting in AD Models

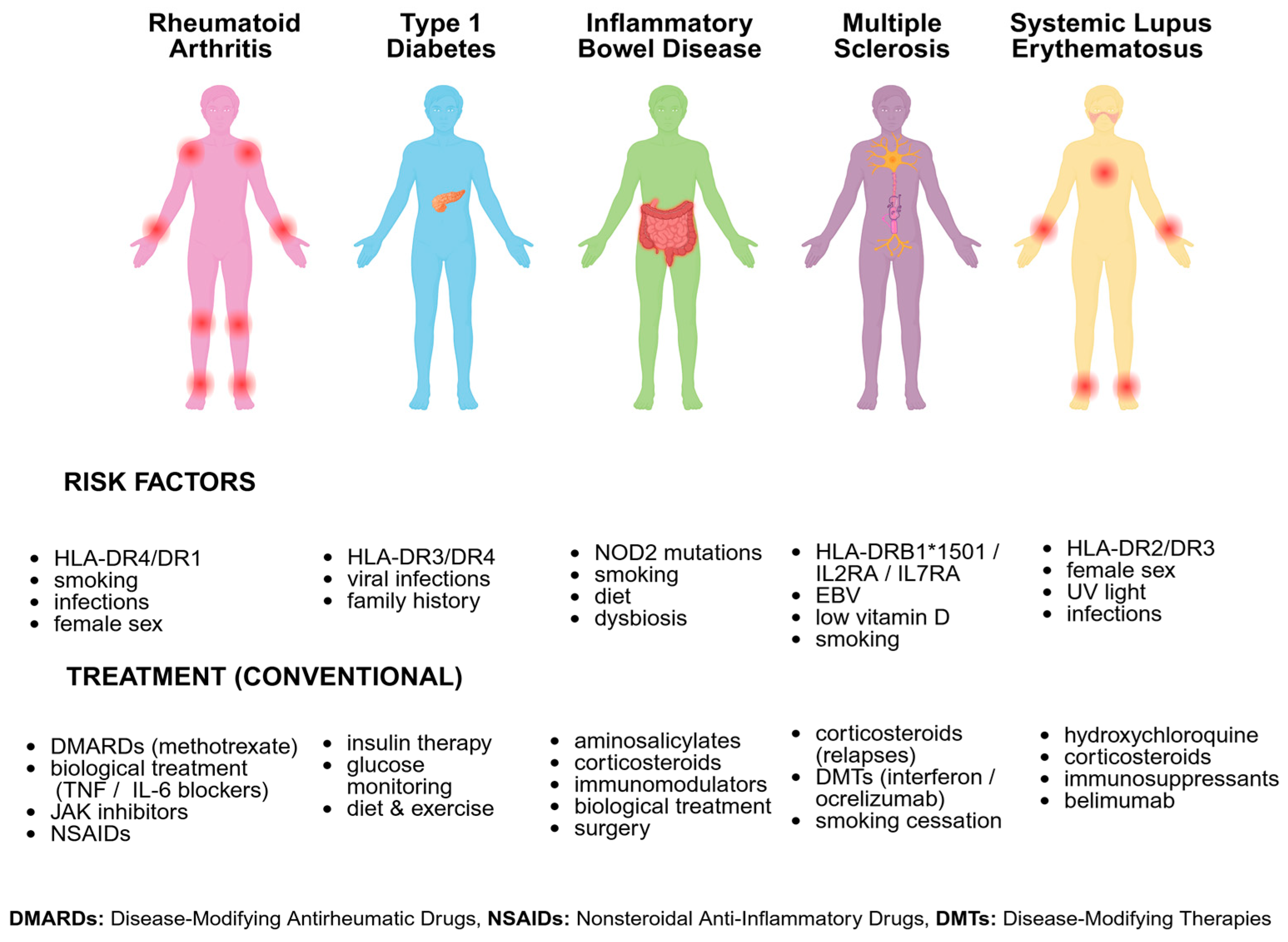

2.3.1. Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

2.3.2. Type 1 Diabetes (T1D)

2.3.3. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

2.3.4. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

2.3.5. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

2.3.6. Key Immune-Mimetic Applications

2.4. Translational Applications in Drug Screening and Mechanistic Studies

2.5. Potential Applications of 3D Bioprinting in Transplantation

2.6. Legal Regulation of Bioprinted Products

3. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conrad, N.; Misra, S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G.; Taylor, P.N.; Mason, J.; Sattar, N.; McMurray, J.J.V.; McInnes, I.B.; et al. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: A population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet 2023, 401, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.R. Prediction and Prevention of Autoimmune Disease in the 21st Century: A Review and Preview. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.M.; Hwang, Y.C.; Liu, I.J.; Lee, C.C.; Tsai, H.Z.; Li, H.J.; Wu, H.C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moszczuk, B.; Mucha, K.; Kucharczyk, R.; Zagożdżon, R. The Role of Glomerular and Serum Expression of Lymphocyte Activating Factors BAFF and APRIL in Patient with Membranous and IgA Nephropathies. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2025, 73, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danieli, M.G.; Antonelli, E.; Gammeri, L.; Longhi, E.; Cozzi, M.F.; Palmeri, D.; Gangemi, S.; Shoenfeld, Y. Intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapy for autoimmune conditions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2025, 24, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiewiórska-Krata, N.; Foroncewicz, B.; Mucha, K.; Zagożdżon, R. Cell therapies for immune-mediated disorders. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1550527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.G.; Kim, H.; Kwon, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Jang, J.; Cho, D.W. Application of 3D bioprinting in the prevention and the therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, N.A.; Ehlen, Q.T.; Greenfield, J.A.; Antonietti, M.; Slavin, B.V.; Nayak, V.V.; Pelaez, D.; Tse, D.T.; Witek, L.; Daunert, S.; et al. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Review for Applications in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Organs-on-a-Chip: A Fast Track for Engineered Human Tissues in Drug Development. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Kathuria, H.; Dubey, N. Advances in 3D bioprinting of tissues/organs for regenerative medicine and in-vitro models. Biomaterials 2022, 287, 121639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawade, D.B.; Oisakede, E.O.; Egbon, E.; Ovsepian, S.V.; Boussios, S. Immune Organoids: A Review of Their Applications in Cancer and Autoimmune Disease Immunotherapy. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, H.; Qiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Developments and Opportunities for 3D Bioprinted Organoids. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Yue, K.; Aleman, J.; Moghaddam, K.M.; Bakht, S.M.; Yang, J.; Jia, W.; Dell’Erba, V.; Assawes, P.; Shin, S.R.; et al. 3D Bioprinting for Tissue and Organ Fabrication. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzl, K.; Lin, S.; Tytgat, L.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Gu, L.; Ovsianikov, A. Bioink properties before, during and after 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Harrysson, O.L.A.; Rao, P.K.; Tamayol, A.; Cormier, D.R.; Zhang, Y.; Rivero, I.V. Extrusion bioprinting: Recent progress, challenges, and future opportunities. Bioprinting 2021, 21, e00116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospodiuk, M.; Dey, M.; Sosnoski, D.; Ozbolat, I.T. The bioink: A comprehensive review on bioprintable materials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, E.; Sarikhani, E.; Montazerian, H.; Ahadian, S.; Costantini, M.; Swieszkowski, W.; Willerth, S.M.; Walus, K.; Mofidfar, M.; Toyserkani, E.; et al. Extrusion and Microfluidic-Based Bioprinting to Fabricate Biomimetic Tissues and Organs. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 1901044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsianikov, A.; Khademhosseini, A.; Mironov, V. The Synergy of Scaffold-Based and Scaffold-Free Tissue Engineering Strategies. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoliu, D.S.; Zagar, C.; Negut, I.; Visan, A.I. Laser-Based Fabrication of Hydrogel Scaffolds for Medicine: From Principles to Clinical Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, T.J.; Jallerat, Q.; Palchesko, R.N.; Park, J.H.; Grodzicki, M.S.; Shue, H.-J.; Ramadan, M.H.; Hudson, A.R.; Feinberg, A.W. Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwarski, D.J.; Hudson, A.R.; Tashman, J.W.; Feinberg, A.W. Emergence of FRESH 3D printing as a platform for advanced tissue biofabrication. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 010904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.E.; Jones, S.W.; ter Horst, B.; Moiemen, N.; Snow, M.; Chouhan, G.; Hill, L.J.; Esmaeli, M.; Moakes, R.J.A.; Holton, J.; et al. Structuring of Hydrogels across Multiple Length Scales for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budharaju, H.; Sundaramurthi, D.; Sethuraman, S. Embedded 3D bioprinting—An emerging strategy to fabricate biomimetic & large vascularized tissue constructs. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32, 356–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.; Wang, Z.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.-H. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norotte, C.; Marga, F.S.; Niklason, L.E.; Forgacs, G. Scaffold-free vascular tissue engineering using bioprinting. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5910–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, L.; Burdick, J.A.; Highley, C.; Lee, S.J.; Morimoto, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Yoo, J.J. Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 21–37, Correction in Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 70. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-018-0020-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.; Camarero-Espinosa, S.; Baker, M.B.; Wieringa, P.; Moroni, L. Bioprinting: From Tissue and Organ Development to in Vitro Models. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10547–10607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavens, K.F.; Alvarez-Dominguez, J.R.; Vo, L.T.; Russ, H.A.; Parent, A.V. Stem cell-based multi-tissue platforms to model human autoimmune diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2022, 66, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duin, S.; Schütz, K.; Ahlfeld, T.; Lehmann, S.; Lode, A.; Ludwig, B.; Gelinsky, M. 3D Bioprinting of Functional Islets of Langerhans in an Alginate/Methylcellulose Hydrogel Blend. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1801631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sun, A.R.; Li, J.; Yuan, T.; Cheng, W.; Ke, L.; Chen, J.; Sun, W.; Mi, S.; Zhang, P. A Three-Dimensional Co-Culture Model for Rheumatoid Arthritis Pannus Tissue. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 764212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Yonezawa, T.; Hubbell, K.; Dai, G.; Cui, X. Inkjet-bioprinted acrylated peptides and PEG hydrogel with human mesenchymal stem cells promote robust bone and cartilage formation with minimal printhead clogging. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 10, 1568–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ngo, G.H.; Hong, W.; Lee, S.H.; Mahajan, V.B.; DeBoer, C. 3D Bioprinting of Cellular Therapeutic Systems in Ophthalmology: From Bioengineered Tissue to Personalized Drug Delivery. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2025, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skylar-Scott, M.A.; Uzel, S.G.M.; Nam, L.L.; Ahrens, J.H.; Truby, R.L.; Damaraju, S.; Lewis, J.A. Biomanufacturing of organ-specific tissues with high cellular density and embedded vascular channels. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimene, D.; Lennox, K.K.; Kaunas, R.R.; Gaharwar, A.K. Advanced Bioinks for 3D Printing: A Materials Science Perspective. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 2090–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M.R. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: An overview. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.B.; Fazel Anvari-Yazdi, A.; Duan, X.; Zimmerling, A.; Gharraei, R.; Sharma, N.K.; Sweilem, S.; Ning, L. Biomaterials/bioinks and extrusion bioprinting. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 38; Staros, R.; Michalak, A.; Rusinek, K.; Mucha, K.; Pojda, Z.; Zagożdżon, R. Perspectives for 3D-Bioprinting in Modeling of Tumor Immune Evasion. Cancers 2022, 14, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, L.; Abubakar, S.; Permatasari, I.; Lawal, A.A.; Uddin, S.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, I. Advanced Biocompatible and Biodegradable Polymers: A Review of Functionalization, Smart Systems, and Sustainable Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Matteo, A.; Bathon, J.M.; Emery, P. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2023, 402, 2019–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravallese, E.M.; Firestein, G.S. Rheumatoid Arthritis—Common Origins, Divergent Mechanisms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.H.; Berman, J.R. What Is Rheumatoid Arthritis? JAMA 2022, 327, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finckh, A.; Gilbert, B.; Hodkinson, B.; Bae, S.C.; Thomas, R.; Deane, K.D.; Alpizar-Rodriguez, D.; Lauper, K. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Kolahi, A.A.; Hoy, D.; Smith, E.; Bettampadi, D.; Mansournia, M.A.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; Ashrafi-Asgarabad, A.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Qorbani, M.; et al. Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Venrooij, W.J.; van Beers, J.J.; Pruijn, G.J. Anti-CCP antibodies: The past, the present and the future. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011, 7, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Broek, M.; Dirven, L.; Klarenbeek, N.B.; Molenaar, T.H.; Han, K.H.; Kerstens, P.J.; Huizinga, T.W.; Dijkmans, B.A.; Allaart, C.F. The association of treatment response and joint damage with ACPA-status in recent-onset RA: A subanalysis of the 8-year follow-up of the BeSt study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.A.; Gurish, M.F.; Marshall, J.L.; Slowikowski, K.; Fonseka, C.Y.; Liu, Y.; Donlin, L.T.; Henderson, L.A.; Wei, K.; Mizoguchi, F.; et al. Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 2017, 542, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivo, R.; Di Franco, M.; Spadaro, A.; Valesini, G. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1108, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, A.H.; Zhang, F.; Dunlap, G.; Gomez-Rivas, E.; Watts, G.F.M.; Faust, H.J.; Rupani, K.V.; Mears, J.R.; Meednu, N.; Wang, R.; et al. Granzyme K+ CD8 T cells form a core population in inflamed human tissue. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo0686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; McInnes, I.B. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schett, G.; Gravallese, E. Bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis: Mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culemann, S.; Grüneboom, A.; Nicolás-Ávila, J.; Weidner, D.; Lämmle, K.F.; Rothe, T.; Quintana, J.A.; Kirchner, P.; Krljanac, B.; Eberhardt, M.; et al. Locally renewing resident synovial macrophages provide a protective barrier for the joint. Nature 2019, 572, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, I.B.; Schett, G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2017, 389, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestein, G.S. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 2003, 423, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Q. Constructing a 3D co-culture in vitro synovial tissue model for rheumatoid arthritis research. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petretta, M.; Villata, S.; Scozzaro, M.P.; Roseti, L.; Favero, M.; Napione, L.; Frascella, F.; Pirri, C.F.; Grigolo, B.; Olivotto, E. In Vitro Synovial Membrane 3D Model Developed by Volumetric Extrusion Bioprinting. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, U.; Ford, E.M.; Ha, B.; Rijns, L.; Chaudhuri, O.; Dankers, P.Y.W.; Kloxin, A.M.; Snedeker, J.G.; Gentleman, E. Engineered hydrogels for mechanobiology. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Lu, Y.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Zheng, A.; Lamb, A.; Yan, Y.; Lipa, K.E.; Lei, G.; Lin, H. Mechanotransduction pathways in articular chondrocytes and the emerging role of estrogen receptor-α. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadessa, A.; Ronca, A.; Salerno, A. Integrating bioprinting, cell therapies and drug delivery towards in vivo regeneration of cartilage, bone and osteochondral tissue. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 858–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Yang, Y. 3D bioprinting technology to construct bone reconstruction research model and its feasibility evaluation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1328078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Song, X.-J.; Lu, X.-C.; Chen, Z.-J.; Li, Y.-W.; Kankala, R.K.; Chen, A.-Z.; Wang, S.-B.; Fu, C.-P. 3D-bioprinted osteochondral model based on hierarchical polymeric microarchitectures for in vitro osteoarthritis drug screening. Int. J. Bioprint. 2025, 11, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.A.; Sant, S.; Cho, S.K.; Goodman, S.B.; Bunnell, B.A.; Tuan, R.S.; Gold, M.S.; Lin, H. Synovial joint-on-a-chip for modeling arthritis: Progress, pitfalls, and potential. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippon, E.M.L.; van Rooijen, L.J.E.; Khodadust, F.; van Hamburg, J.P.; van der Laken, C.J.; Tas, S.W. A novel 3D spheroid model of rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue incorporating fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1188835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Wen, J.; Sun, Y.; He, M. Synovial Organoids and Cell Culture Models: An Ideal Platform for Exploring Traditional Chinese Medicine in Rheumatoid Arthritis. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 36904–36916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Darvishi, A.; Sabzevari, A. A review of advanced hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1340893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMeglio, L.A.; Evans-Molina, C.; Oram, R.A. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2018, 391, 2449–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.A.; Robinson, T.I.G.; Linklater, S.E.; Wang, F.; Colagiuri, S.; de Beaufort, C.; Donaghue, K.C.; Magliano, D.J.; Maniam, J.; Orchard, T.J.; et al. Global incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021 with projection to 2040: A modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 741–760, Erratum in Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Isom, S.; Dolan, L.; Imperatore, G.; Linder, B.; Marcovina, S.; Pettitt, D.J.; et al. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.A. Immunogenetics of type 1 diabetes: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2015, 64, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, H.; Valdes, A.M.; Noble, J.; Carlson, J.A.; Varney, M.; Concannon, P.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Todd, J.A.; Bonella, P.; Fear, A.L.; et al. HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: Analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concannon, P.; Rich, S.S.; Nepom, G.T. Genetics of type 1A diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjouri, M.R.; Aob, P.; Mansoori Derakhshan, S.; Shekari Khaniani, M.; Chiti, H.; Ramazani, A. Association study of IL2RA and CTLA4 Gene Variants with Type I Diabetes Mellitus in children in the northwest of Iran. Bioimpacts 2016, 6, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcastro, E.; Cudini, A.; Mezzani, I.; Petrini, S.; D’Oria, V.; Schiaffini, R.; Scarsella, M.; Russo, A.L.; Fierabracci, A. Effect of the autoimmune-associated genetic variant PTPN22 R620W on neutrophil activation and function in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1554570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio, F.; Carré, A.; Korenkov, D.; Zhou, Z.; Apaolaza, P.; Tuomela, S.; Burgos-Morales, O.; Snowhite, I.; Perez-Hernandez, J.; Brandao, B.; et al. Coxsackievirus infection induces direct pancreatic β cell killing but poor antiviral CD8+ T cell responses. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, M.; Vaarala, O.; Hermann, R.; Salminen, K.; Vahlberg, T.; Veijola, R.; Hyöty, H.; Knip, M.; Simell, O.; Ilonen, J. Enteral virus infections in early childhood and an enhanced type 1 diabetes-associated antibody response to dietary insulin. J. Autoimmun. 2006, 27, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.G.; Nepom, G.T. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity 2010, 32, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, T.; Wiles, T.A.; Baker, R.L.; Bradley, B.; Barbour, G.; Reisdorph, R.; Armstrong, M.; Powell, R.L.; Reisdorph, N.; Kumar, N.; et al. Pathogenic CD4 T cells in type 1 diabetes recognize epitopes formed by peptide fusion. Science 2016, 351, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roep, B.O.; Arden, S.D.; de Vries, R.R.; Hutton, J.C. T-cell clones from a type-1 diabetes patient respond to insulin secretory granule proteins. Nature 1990, 345, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrack, A.L.; Martinov, T.; Fife, B.T. T Cell-Mediated Beta Cell Destruction: Autoimmunity and Alloimmunity in the Context of Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizirik, D.L.; Sammeth, M.; Bouckenooghe, T.; Bottu, G.; Sisino, G.; Igoillo-Esteve, M.; Ortis, F.; Santin, I.; Colli, M.L.; Barthson, J.; et al. The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: Expression of candidate genes for type 1 diabetes and the impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonen, J.; Lempainen, J.; Veijola, R. The heterogeneous pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Thompson, M.L.; Filipp, S.L.; Grajo, J.R.; Nambam, B.; Beegle, R.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Gurka, M.J.; Atkinson, M.A.; Schatz, D.A.; Haller, M.J. Relative Pancreas Volume Is Reduced in First-Degree Relatives of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribezzi, D.; Català, P.; Pignatelli, C.; Citro, A.; Levato, R. Bioprinting and synthetic biology approaches to engineer functional endocrine pancreatic constructs. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.; Perrier, Q.; Rengaraj, A.; Bowlby, J.; Byers, L.; Peveri, E.; Jeong, W.; Ritchey, T.; Gambelli, A.M.; Rossi, A.; et al. State of the Art of Bioengineering Approaches in Beta-Cell Replacement. Curr. Transpl. Rep. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, Q.; Jeong, W.; Rengaraj, A.; Byers, L.; Gonzalez, G.; Peveri, E.; Miller, J.; Opara, E.; Bottino, R.; Mikhailov, A.; et al. Breakthroughs in 3D printing: Functional human islets in an alginate-dECM bioink. Cytotherapy 2025, 27, S32–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.D.; Yeh, W.I.; Arnoletti, J.M.; Brown, M.E.; Posgai, A.L.; Mathews, C.E.; Brusko, T.M. Modeling cell-mediated immunity in human type 1 diabetes by engineering autoreactive CD8+ T cells. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1142648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daramola, O.; Abrahamse, H.; Crous, A. Advancements in photobiomodulation for generating functional beta cells from adipose derived stem cells in 3D culture: A comprehensive review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Comas, J.; Ramón-Azcón, J. Islet-on-a-chip for the study of pancreatic β-cell function. In Vitro Models 2022, 1, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Song, D.; Wang, X. 3D Bioprinting for Pancreas Engineering/Manufacturing. Polymers 2022, 14, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattner, N. Immune cell infiltration in the pancreas of type 1, type 2 and type 3c diabetes. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 14, 20420188231185958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Ren, J.; Wu, X. Advances in hydrogels for capturing and neutralizing inflammatory cytokines. J. Tissue Eng. 2025, 16, 20417314251342175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaneh, S.; Kemény, L.; Ghaffarinia, A.; Yarani, R.; Veréb, Z. Three-dimensional bioprinting of functional β-islet-like constructs. Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espona-Noguera, A.; Ciriza, J.; Cañibano-Hernández, A.; Orive, G.; Hernández, R.M.M.; Saenz Del Burgo, L.; Pedraz, J.L. Review of Advanced Hydrogel-Based Cell Encapsulation Systems for Insulin Delivery in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.G.; Millman, J.R. Applications of iPSC-derived beta cells from patients with diabetes. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, C.; Campo, F.; Neroni, A.; Piemonti, L.; Citro, A. Bioengineering the Vascularized Endocrine Pancreas: A Fine-Tuned Interplay Between Vascularization, Extracellular-Matrix-Based Scaffold Architecture, and Insulin-Producing Cells. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q. A Comprehensive Review and Update on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 7247238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombel, J.F.; D’Haens, G.; Lee, W.J.; Petersson, J.; Panaccione, R. Outcomes and Strategies to Support a Treat-to-target Approach in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Pang, Z.; Chen, W.; Ju, S.; Zhou, C. The epidemiology and risk factors of inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 22529–22542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frolkis, A.D.; Dykeman, J.; Negrón, M.E.; Debruyn, J.; Jette, N.; Fiest, K.M.; Frolkis, T.; Barkema, H.W.; Rioux, K.P.; Panaccione, R.; et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Lytras, T.; Bonovas, S. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 647–659.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstrup, H.; Mohamed, H.A.S.; Honoré, J.; Schullehner, J.; Sigsgaard, T.; Forsberg, B.; Oudin, A. Air pollution exposure and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic literature review of epidemiological and mechanistic studies. Front. Environ. Health 2024, 3, 1463016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Leddin, D.; Malekzadeh, R. Mini Review: The Impact of Climate Change on Gastrointestinal Health. Middle East. J. Dig. Dis. 2023, 15, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, S.A.; Arce, M.; Khaja, A.; Fernandez, M.; Naser, N.; Elwasila, S.; Thanigachalam, S. Role of ATG16L, NOD2 and IL23R in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micati, D.; Hlavca, S.; Chan, W.H.; Abud, H.E. Harnessing 3D models to uncover the mechanisms driving infectious and inflammatory disease in the intestine. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torras, N.; Zabalo, J.; Abril, E.; Carré, A.; García-Díaz, M.; Martínez, E. A bioprinted 3D gut model with crypt-villus structures to mimic the intestinal epithelial-stromal microenvironment. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 153, 213534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, L.R.; Nguyen, T.V.; Garcia-Mojica, S.; Shah, V.; Le, A.V.; Peier, A.; Visconti, R.; Parker, E.M.; Presnell, S.C.; Nguyen, D.G.; et al. Bioprinted 3D Primary Human Intestinal Tissues Model Aspects of Native Physiology and ADME/Tox Functions. iScience 2018, 2, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Huang, S. Intestinal organoids in inflammatory bowel disease: Advances, applications, and future directions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1517121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Huh, D.; Hamilton, G.; Ingber, D.E. Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinal peristalsis-like motions and flow. Lab. Chip 2012, 12, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Lee, H. Engineering Hydrogels for the Development of Three-Dimensional In Vitro Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Paul, H.T.; Guo, C.; Kaplan, D.L. 3D bioengineered tissue model of the large intestine to study inflammatory bowel disease. Biomaterials 2019, 225, 119517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Blanchard, A.; Walker, J.R.; Graff, L.A.; Miller, N.; Bernstein, C.N. Common symptoms and stressors among individuals with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodat, Y.A.; Kang, M.G.; Kiaee, K.; Kim, G.J.; Martinez, A.F.H.; Rosenkranz, A.; Bae, H.; Shin, S.R. Human-Derived Organ-on-a-Chip for Personalized Drug Development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 5471–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehab, S.; Gaser, O.A.; Dayem, A.A. Hypoxia and Multilineage Communication in 3D Organoids for Human Disease Modeling. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrachi, T.; Portone, A.; Arnaud, G.F.; Ganzerli, F.; Bergamini, V.; Resca, E.; Accorsi, L.; Ferrari, A.; Delnevo, A.; Rovati, L.; et al. Novel bioprinted 3D model to human fibrosis investigation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derman, I.D.; Moses, J.C.; Rivera, T.; Ozbolat, I.T. Understanding the cellular dynamics, engineering perspectives and translation prospects in bioprinting epithelial tissues. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 43, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucafò, M.; Muzzo, A.; Marcuzzi, M.; Giorio, L.; Decorti, G.; Stocco, G. Patient-derived organoids for therapy personalization in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 2636–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jelcic, I.; Mühlenbruch, L.; Haunerdinger, V.; Toussaint, N.C.; Zhao, Y.; Cruciani, C.; Faigle, W.; Naghavian, R.; Foege, M.; et al. HLA-DR15 Molecules Jointly Shape an Autoreactive T Cell Repertoire in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell 2020, 183, 1264–1281.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Multiple sclerosis genomic map implicates peripheral immune cells and microglia in susceptibility. Science 2019, 365, eaav7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Murúa, S.; Farez, M.F.; Quintana, F.J. The Immune Response in Multiple Sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2022, 17, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berer, K.; Mues, M.; Koutrolos, M.; Rasbi, Z.A.; Boziki, M.; Johner, C.; Wekerle, H.; Krishnamoorthy, G. Commensal microbiota and myelin autoantigen cooperate to trigger autoimmune demyelination. Nature 2011, 479, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.; Chitnis, T. Association Between Cigarette Smoking and Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokry, L.E.; Ross, S.; Timpson, N.J.; Sawcer, S.; Davey Smith, G.; Richards, J.B. Obesity and Multiple Sclerosis: A Mendelian Randomization Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, K.C.; Munger, K.L.; Köchert, K.; Arnason, B.G.; Comi, G.; Cook, S.; Goodin, D.S.; Filippi, M.; Hartung, H.P.; Jeffery, D.R.; et al. Association of Vitamin D Levels With Multiple Sclerosis Activity and Progression in Patients Receiving Interferon Beta-1b. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelcic, I.; Al Nimer, F.; Wang, J.; Lentsch, V.; Planas, R.; Jelcic, I.; Madjovski, A.; Ruhrmann, S.; Faigle, W.; Frauenknecht, K.; et al. Memory B Cells Activate Brain-Homing, Autoreactive CD4+ T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell 2018, 175, 85–100.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverman, J.M. Immune tolerance in multiple sclerosis. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 241, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baecher-Allan, C.; Kaskow, B.J.; Weiner, H.L. Multiple Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Immunotherapy. Neuron 2018, 97, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendrou, C.A.; Fugger, L.; Friese, M.A. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.P.; Hemmer, B.; Lublin, F.; Montalban, X.; Rammohan, K.W.; Selmaj, K.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicaise, A.M.; Wagstaff, L.J.; Willis, C.M.; Paisie, C.; Chandok, H.; Robson, P.; Fossati, V.; Williams, A.; Crocker, S.J. Cellular senescence in progenitor cells contributes to diminished remyelination potential in progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9030–9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Bessler, N.; Figler, K.; Buchholz, M.B.; Rios, A.C.; Malda, J.; Levato, R.; Caiazzo, M. Bioprinting Neural Systems to Model Central Nervous System Diseases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, T.; Onesto, V.; Banerjee, D.; Guo, S.; Polini, A.; Vogt, C.; Viswanath, A.; Esworthy, T.; Cui, H.; O’Donnell, A.; et al. 3D bioprinting in tissue engineering: Current state-of-the-art and challenges towards system standardization and clinical translation. Biofabrication 2025, 17, 042003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Tomaskovic-Crook, E.; Lozano, R.; Chen, Y.; Kapsa, R.M.; Zhou, Q.; Wallace, G.G.; Crook, J.M. Functional 3D Neural Mini-Tissues from Printed Gel-Based Bioink and Human Neural Stem Cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Mathivanan, S.; Kong, L.; Tao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Zhao, X.; et al. 3D bioprinting of human neural tissues with functional connectivity. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 260–274.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, M.; Ning, L.; King, A.; Hwang, B.; Jin, L.; Serpooshan, V.; Sloan, S.A. 3D Bioprinting of Neural Tissues. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2001600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaki, T.; Sivathanu, V.; Kamm, R.D. Engineered 3D vascular and neuronal networks in a microfluidic platform. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, S.; Mäkinen, A.; Ylä-Outinen, L.; Huhtala, H.; Elovaara, I.; Narkilahti, S. Effects of inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-6 on the viability and functionality of human pluripotent stem cell-derived neural cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 331, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, A.; Hao, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; He, J.; Gao, L.; Mao, X.; Paz, R. In vitro model of the glial scar. Int. J. Bioprint. 2019, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.I.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L. Microfluidic blood-brain barrier model provides in vivo-like barrier properties for drug permeability screening. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelt-Menzel, A.; Oerter, S.; Mathew, S.; Haferkamp, U.; Hartmann, C.; Jung, M.; Neuhaus, W.; Pless, O. Human iPSC-Derived Blood-Brain Barrier Models: Valuable Tools for Preclinical Drug Discovery and Development? Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2020, 55, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.H.Y.; Yu, F.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z. 3D Bioprinting for Next-Generation Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Gordon, C.; Crow, M.K.; Touma, Z.; Urowitz, M.B.; van Vollenhoven, R.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Hughes, G. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durcan, L.; O’Dwyer, T.; Petri, M. Management strategies and future directions for systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Lancet 2019, 393, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörner, T.; Furie, R. Novel paradigms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet 2019, 393, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L.; Guyatt, G.; Fink, H.A.; Cannon, M.; Grossman, J.; Hansen, K.E.; Humphrey, M.B.; Lane, N.E.; Magrey, M.; Miller, M.; et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 1521–1537, Erratum in Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, M.; Salmaso, L.; Barbiellini Amidei, C.; Fedeli, U.; Bellio, S.; Iaccarino, L.; Doria, A.; Saia, M. Mortality and causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus over the last decade: Data from a large population-based study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 112, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodke-Puranik, Y.; Niewold, T.B. Immunogenetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2015, 64, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rullo, O.J.; Tsao, B.P. Recent insights into the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, ii56–ii61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, M.K. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: Risks, mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.Y.; Hahn, J.; Malspeis, S.; Stevens, E.F.; Karlson, E.W.; Sparks, J.A.; Yoshida, K.; Kubzansky, L.; Costenbader, K.H. Association of a Combination of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors With Reduced Risk of Incident Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, M.K. Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 316, 359–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, D.A.; Poenariu, I.S.; Crînguș, L.I.; Vreju, F.A.; Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Tica, A.A.; Padureanu, V.; Dumitrascu, R.M.; Banicioiu-Covei, S.; Dinescu, S.C.; et al. JAK/STAT pathway in pathology of rheumatoid arthritis (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 3498–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokos, G.C. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2110–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.R.W.; Drenkard, C.; Falasinnu, T.; Hoi, A.; Mak, A.; Kow, N.Y.; Svenungsson, E.; Peterson, J.; Clarke, A.E.; Ramsey-Goldman, R. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 515–532, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-021-00690-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jia, J. Bioprinted vascular tissue: Assessing functions from cellular, tissue to organ levels. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhu, H.; Bosholm, C.C.; Beiner, D.; Duan, Z.; Shetty, A.K.; Mou, S.S.; Kramer, P.A.; Barroso, L.F.; Liu, H.; et al. Precision nephrotoxicity testing using 3D in vitro models. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ruan, D.; Huang, M.; Tian, M.; Zhu, K.; Gan, Z.; Xiao, Z. Harnessing the potential of hydrogels for advanced therapeutic applications: Current achievements and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, X. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Updated insights on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Choi, Y.Y.; Kwon, E.J.; Seo, S.; Kim, W.Y.; Park, S.H.; Park, S.; Chin, H.J.; Na, K.Y.; Kim, S. Characterizing Glomerular Barrier Dysfunction with Patient-Derived Serum in Glomerulus-on-a-Chip Models: Unveiling New Insights into Glomerulonephritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Jin, G.; Ju, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, L.; Fu, Y.; Hou, R.; Atala, A.; Zhao, W. Bioprinting small-diameter vascular vessel with endothelium and smooth muscle by the approach of two-step crosslinking process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Kunz, M. Current concepts of photosensitivity in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 939594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Shin, S.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Knowles, J.C.; Lee, H.-H.; Kim, H.-W. Adaptive immunity of materials: Implications for tissue healing and regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 41, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenko, S.; Nagalla, R.R.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Palomba, F.; David, L.M.; Nguyen, R.Q.; Gay, D.; Almet, A.A.; Digman, M.A.; Nie, Q.; et al. Hydrogel crosslinking modulates macrophages, fibroblasts, and their communication, during wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremmel, D.M.; Sackett, S.D.; Feeney, A.K.; Mitchell, S.A.; Schaid, M.D.; Polyak, E.; Chlebeck, P.J.; Gupta, S.; Kimple, M.E.; Fernandez, L.A.; et al. A human pancreatic ECM hydrogel optimized for 3-D modeling of the islet microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisconti, F.; Vilardo, B.; Corallo, G.; Scalera, F.; Gigli, G.; Chiocchetti, A.; Polini, A.; Gervaso, F. An Assist for Arthritis Studies: A 3D Cell Culture of Human Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes by Encapsulation in a Chitosan-Based Hydrogel. Adv. Ther. 2024, 7, 2400166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyer, A.; Beyer, L.; Simon, C.; Stemmler, F.; Englbrecht, M.; Beyer, C.; Rech, J.; Manger, B.; Krönke, G.; Schett, G.; et al. Development of three-dimensional prints of arthritic joints for supporting patients’ awareness to structural damage. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanns, C.; de Vries, R.H.W.; Rademakers, T.; Stell, A.; de Bont, D.F.A.; da Silva Filho, O.P.; Jetten, M.J.; Mota, C.D.; Mohammed, S.G.; Vaithilingam, V.; et al. Assessing mesh size and diffusion of alginate bioinks: A crucial factor for successful bioprinting functional pancreatic islets. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 34, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poklar, M.; Ravikumar, K.; Wiegand, C.; Mizerak, B.; Wang, R.; Florentino, R.M.; Liu, Z.; Soto-Gutierrez, A.; Kumta, P.N.; Banerjee, I. Bioprinting of human primary and iPSC-derived islets with retained and comparable functionality. Biofabrication 2025, 17, 035028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, A.; Mutlu-Ağardan, N.B.; Özgenç Çınar, Ö.; Ceylan, A.; Uyar, R.; Yurdakök Dikmen, B.; Acartürk, F. In vitro/in vivo evaluation of 3D bioprinted silk fibroin hydrogels for IBD: A dual mesalazine and TNF-α siRNA approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 213, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, G.; Montescagli, M.; Di Giulio, G.; Augello, A.; Ferrara, V.; Minopoli, A.; Evangelista, D.; Marras, M.; Artemi, G.; Caretto, A.A.; et al. 3D-Bioprinting of Stromal Vascular Fraction for Gastrointestinal Regeneration. Gels 2025, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat, I.T. Bioprinting scale-up tissue and organ constructs for transplantation. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Yue, K.; Zhu, K.; Liu, W.; Pi, Q.; Byambaa, B.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Shin, S.R.; et al. Direct 3D bioprinting of perfusable vascular constructs using a blend bioink. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 58–68, Correction in Biomaterials 2025, 322, 123364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, F.; Jang, J.; Ha, D.-H.; Won Kim, S.; Rhie, J.-W.; Shim, J.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Cho, D.-W. Printing three-dimensional tissue analogues with decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbagh Moghaddam, F.; Anvar, A.; Ilkhani, E.; Dadgar, D.; Rafiee, M.; Ranjbaran, N.; Mortazavi, P.; Ghoreishian, S.M.; Huh, Y.S.; Makvandi, P. Advances in engineering immune-tumor microenvironments on-a-chip: Integrative microfluidic platforms for immunotherapy and drug discovery. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldo, P.B.; Craveiro, V.; Guller, S.; Mor, G. Effect of Culture Conditions on the Phenotype of THP-1 Monocyte Cell Line. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 70, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Song, Y. Generation and clinical potential of functional T lymphocytes from gene-edited pluripotent stem cells. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Kempf, H.; Hetzel, M.; Hesse, C.; Hashtchin, A.R.; Brinkert, K.; Schott, J.W.; Haake, K.; Kühnel, M.P.; Glage, S.; et al. Bioreactor-based mass production of human iPSC-derived macrophages enables immunotherapies against bacterial airway infections. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, P.; Jullienne, R.; He, Z.; Aldossary, M.; Acquart, S.; Cognasse, F.; Thuret, G. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, A.; Swioklo, S.; Connon, C.J. 3D bioprinting of a corneal stroma equivalent. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 173, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorkio, A.; Koch, L.; Koivusalo, L.; Deiwick, A.; Miettinen, S.; Chichkov, B.; Skottman, H. Human stem cell based corneal tissue mimicking structures using laser-assisted 3D bioprinting and functional bioinks. Biomaterials 2018, 171, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Campos, D.F.; Rohde, M.; Ross, M.; Anvari, P.; Blaeser, A.; Vogt, M.; Panfil, C.; Yam, G.H.; Mehta, J.S.; Fischer, H.; et al. Corneal bioprinting utilizing collagen-based bioinks and primary human keratocytes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grönroos, P.; Mörö, A.; Puistola, P.; Hopia, K.; Huuskonen, M.; Viheriälä, T.; Ilmarinen, T.; Skottman, H. Bioprinting of human pluripotent stem cell derived corneal endothelial cells with hydrazone crosslinked hyaluronic acid bioink. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchels, F.P.; Feijen, J.; Grijpma, D.W. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6121–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenovska, T.; Choong, P.F.; Wallace, G.G.; O’Connell, C.D. The regulatory challenge of 3D bioprinting. Regen. Med. 2023, 18, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukelis, K.; Koutsomarkos, N.; Mikos, A.G.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Advances in 3D bioprinting for regenerative medicine applications. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielniok, K.; Rusinek, K.; Słysz, A.; Lachota, M.; Bączyńska, E.; Wiewiórska-Krata, N.; Szpakowska, A.; Ciepielak, M.; Foroncewicz, B.; Mucha, K.; et al. 3D-Bioprinted Co-Cultures of Glioblastoma Multiforme and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Indicate a Role for Perivascular Niche Cells in Shaping Glioma Chemokine Microenvironment. Cells 2024, 13, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, N.; Hosseini, S.A.; Dalan, A.B.; Mohammadrezaei, D.; Goldman, A.; Kohandel, M. Controlled tumor heterogeneity in a co-culture system by 3D bio-printed tumor-on-chip model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visalakshan, R.M.; Lowrey, M.K.; Sousa, M.G.C.; Helms, H.R.; Samiea, A.; Schutt, C.E.; Moreau, J.M.; Bertassoni, L.E. Opportunities and challenges to engineer 3D models of tumor-adaptive immune interactions. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1162905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.C.; Alvites, R.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Moreira, A.; Coelho, A.; Santos, J.D.; Atayde, L.; Alves, N.; Maurício, A.C. Three-Dimensional Printing/Bioprinting and Cellular Therapies for Regenerative Medicine: Current Advances. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perin, F.; Ouyang, L.; Lim, K.S.; Motta, A.; Maniglio, D.; Moroni, L.; Mota, C. Bioprinted Constructs in the Regulatory Landscape: Current State and Future Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2025, e04037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitorino, R.; Ghavami, S. Convergence: Multi-omics and AI are reshaping the landscape biomedical research. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1872, 168027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakare, K.; Jerpseth, L.; Pei, Z.; Elwany, A.; Quek, F.; Qin, H. Bioprinting of Organ-on-Chip Systems: A Literature Review from a Manufacturing Perspective. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Typical Resolution (µm) | Cell Viability (%) | Key Advantages | Main Limitations | Representative Applications in AD Modeling | Reference/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-based bioprinting | 100–300 | ~75–90 | Supports highly viscous bioinks (e.g., alginate/methylcellulose); enables macroporous scaffolds with controlled architecture; maintains islet morphology and glucose responsiveness | Potential shear stress during printing; reduced insulin response over time; limited diffusion in larger constructs | Pancreatic islet constructs for T1D (viable, glucose-responsive islets within Alg/MC scaffolds) | Duin et al., 2019 [30] |

| 100–300 | 70–90 | Handles viscous, high-cell-density bioinks; supports multi-material fabrication; simple and cost-effective setup | High shear stress on cells; limited resolution; slower printing speed | Synovial and osteochondral constructs for RA (3D co-culture pannus tissue models) | Lin et al., 2021 [31] | |

| Inkjet bioprinting | ~20–30 | ~87–90 | High printing resolution and throughput; non-contact cell placement; compatible with low-viscosity bioinks; minimal nozzle clogging with PEG-based hydrogels | Limited to low-viscosity inks; potential for cell damage due to thermal stress; low mechanical strength of printed hydrogels | Cytokine gradient mapping and cell–matrix interaction studies in inflammatory and musculoskeletal models (RA, IBD) | Gao et al., 2015 [32] |

| Laser-assisted bioprinting | 10–50 | 85–95 | High precision and resolution; supports delicate cell types like stem cells; enables micro-structured tissues (e.g., cornea, retina) with minimal shear stress | High operational cost; complex setup and calibration; limited scalability for large constructs | Bioengineered corneal and retinal constructs for studying immune privilege, inflammation, and tissue repair mechanisms in ocular autoimmune diseases (e.g., uveitis, autoimmune keratitis) | Kim et al., 2025 [33] |

| 3D-embedded/SWIFT bioprinting | 100–400 | >90 | Enables embedded vascular networks within densely cellular organoid matrices; supports perfusion and long-term viability; maintains native tissue microarchitecture; scalable to organ-level constructs | Limited resolution below 400 µm due to organoid size; complex fabrication workflow; slow printing and perfusion setup; incomplete endothelialization of channels | Perfusable, immune-vascularized microtissues for modeling inflammation, hypoxia, and tissue–immune cell interactions in diseases such as RA, SLE, or T1D | Skylar-Scott et al., 2019 [34] |

| Disease Model | Cells Used | Bioink/Scaffold | Key Features & Innovations | Reference/Year | Main Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | MH7A synoviocytes, EA.hy926 endothelial cells | Gelatin/alginate hydrogel | TNF induced VEGF/ANG expression, methotrexate response | Lin et al., 2021 [31] | Tissue modeling, drug screening |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Human fibroblast-like synoviocytes | Chitosan–Matrigel hydrogel composite | Stable 3D FLS culture mimicking synovial microarchitecture | Bisconti et al., 2024 [168] | Synovial tissue modelling, drug testing |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (joint anatomy) | (imaging data) | PLA or photopolymer resin (no cells) | CT-based RA joint 3D prints for anatomical erosion | Kleyer et al., 2017 [169] | Surgical education, visualization |

| Type 1 Diabetes | INS1E β-cell line, rat and human pancreatic islets | 1.5% ultrapure alginate hydrogel | Preserved islet viability and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion | Hermanns et al., 2025 [170] | Islet transplantation optimization and metabolic modeling |

| Type 1 Diabetes | Primary human islets, iPSC-derived islets | Alginate/methylcellulose bioink (3%/6%) | Human and iPSC-derived islets; maintained glucose responsiveness and gene expression | Poklar et al., 2025 [171] | Personalized islet bioprinting, autologous cell therapy |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | RAW 264.7 macrophages; in vivo Balb/c mouse model | Silk fibroin/alginate/hyaluronic acid hydrogel with mesalazine + chitosan:TNF-α siRNA | Hydrogels reduced inflammation and improved mucosal healing in vivo | Yıldız et al., 2025 [172] | Oral bioprinted hydrogel for combinatorial IBD therapy |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Patient-derived MSCs, fibroblasts, endothelial and epithelial cells | GelMA hydrogel | Promotion of epithelial repair, tight junction formation, fibroblast chemotaxis, and angiogenesis | Perini et. al, 2025 [173] | Regenerative medicine platform for IBD and mucosal healing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wiewiórska-Krata, N.; Foroncewicz, B.; Zagożdżon, R.; Mucha, K. 3D Bioprinting Strategies in Autoimmune Disease Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010343

Wiewiórska-Krata N, Foroncewicz B, Zagożdżon R, Mucha K. 3D Bioprinting Strategies in Autoimmune Disease Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010343

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiewiórska-Krata, Natalia, Bartosz Foroncewicz, Radosław Zagożdżon, and Krzysztof Mucha. 2026. "3D Bioprinting Strategies in Autoimmune Disease Models" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010343

APA StyleWiewiórska-Krata, N., Foroncewicz, B., Zagożdżon, R., & Mucha, K. (2026). 3D Bioprinting Strategies in Autoimmune Disease Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010343