Identification of Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from Amino Derivatives of Epoxyalantolactone: In Silico and In Vitro Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

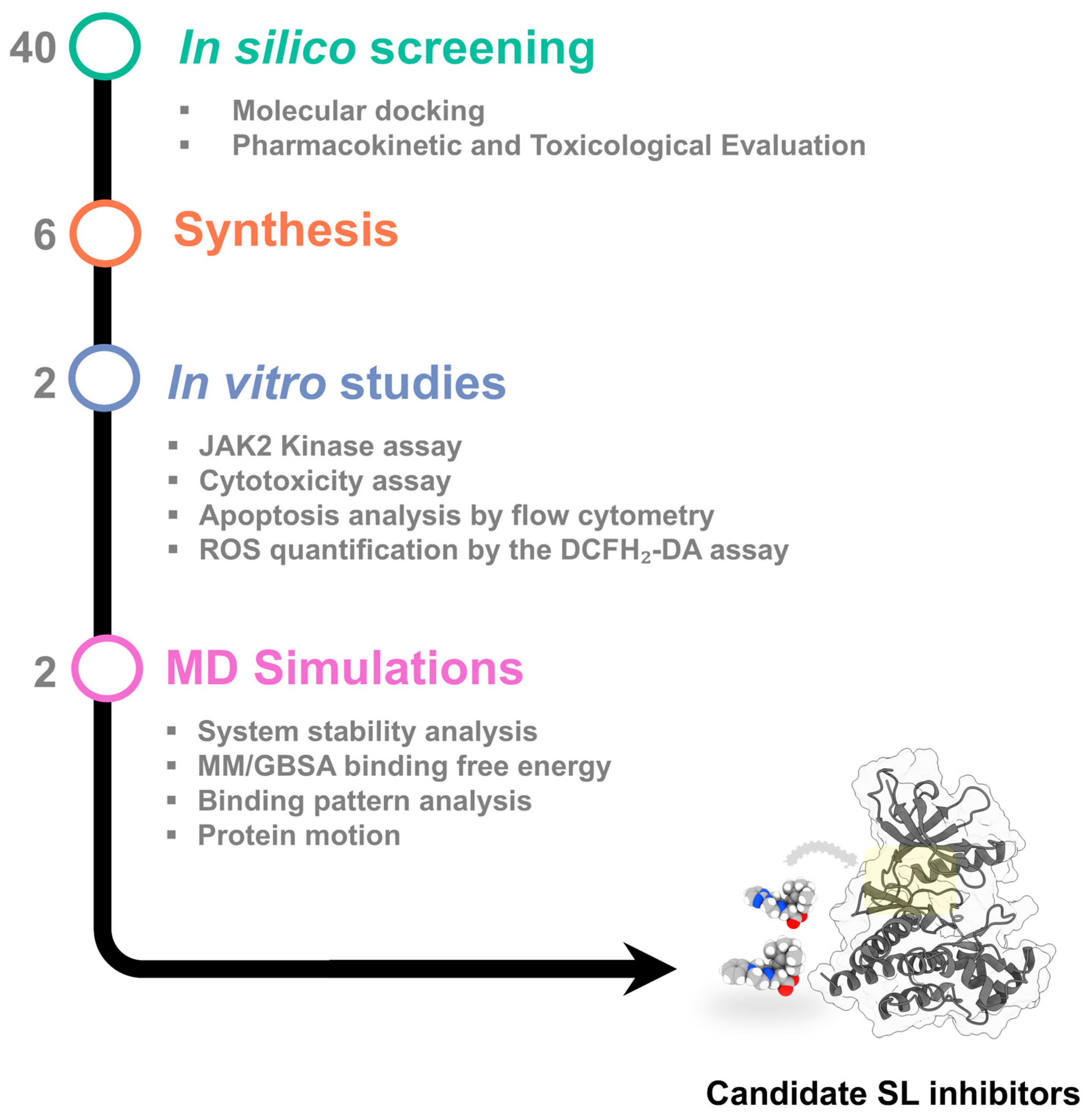

2. Results and Discussion

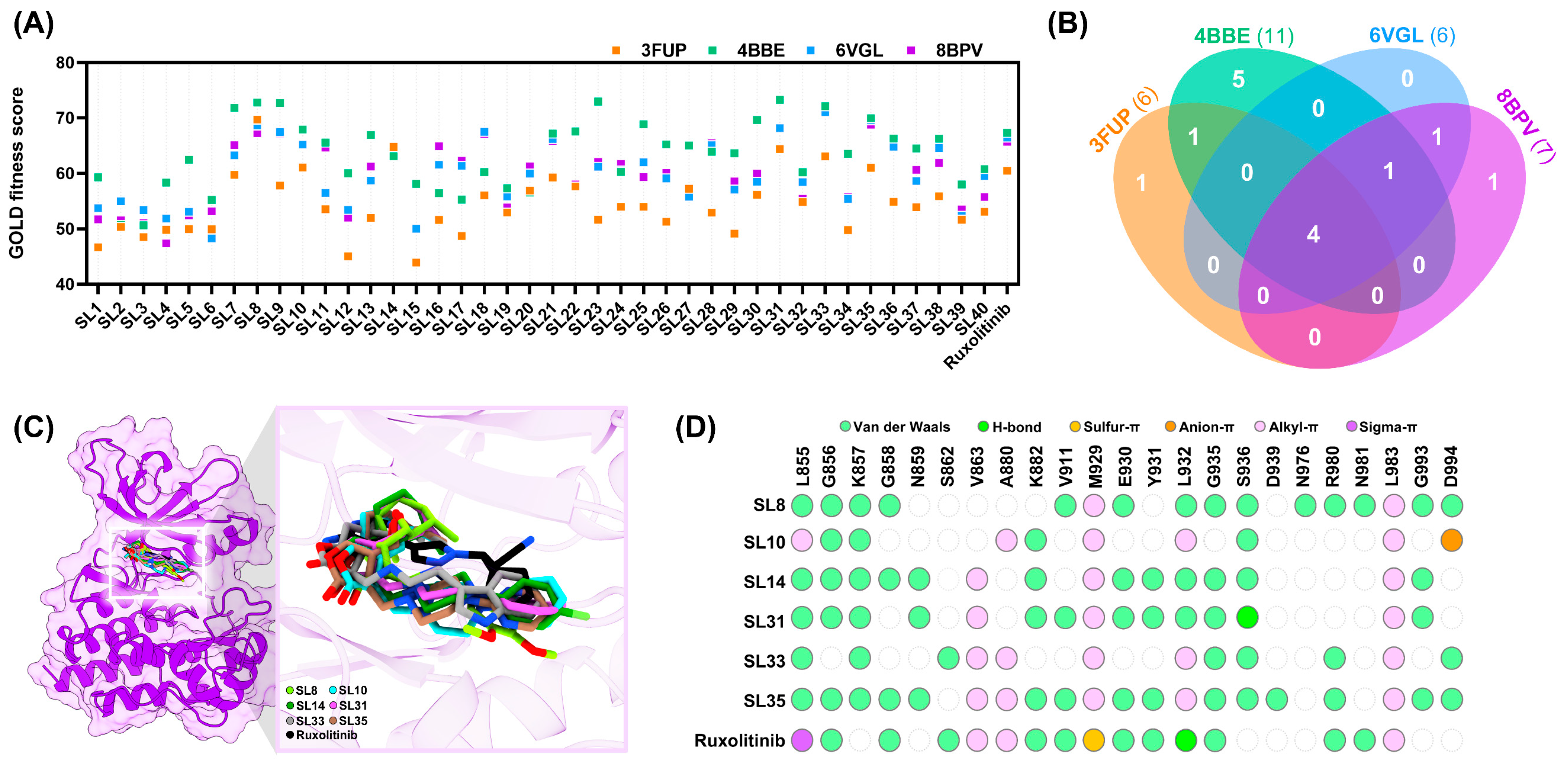

2.1. In Silico Evaluation of Compound Binding Affinity, Pharmacokinetics, and Safety Profiles

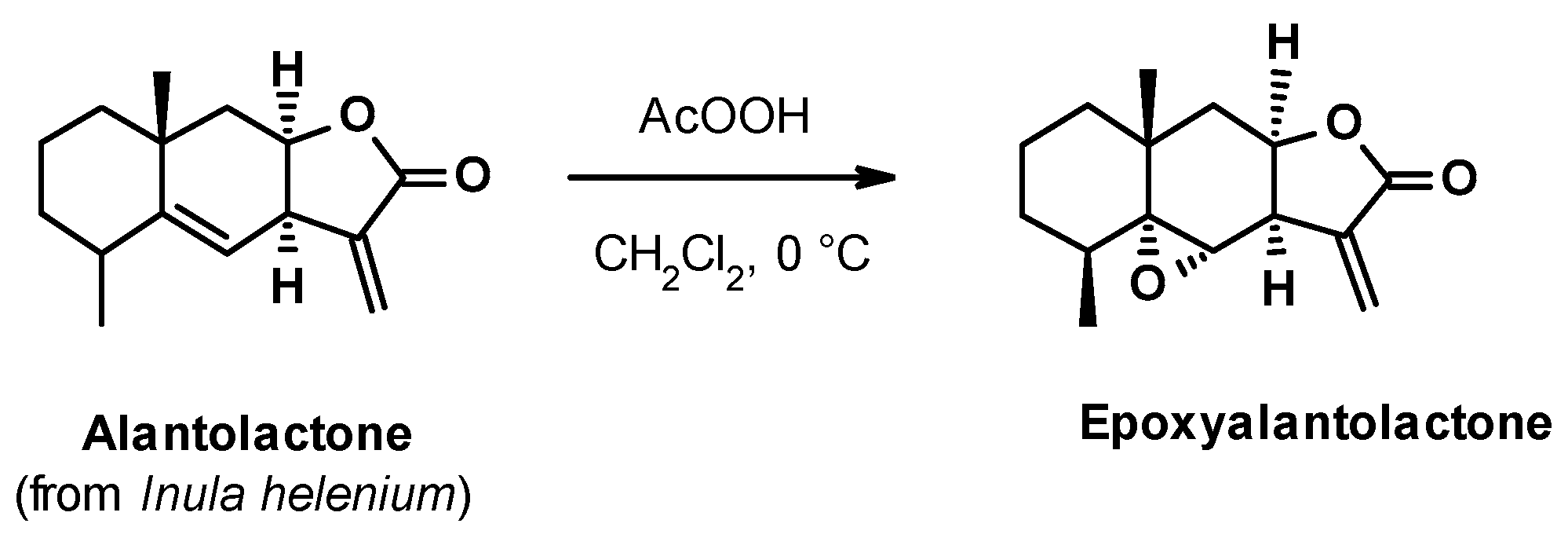

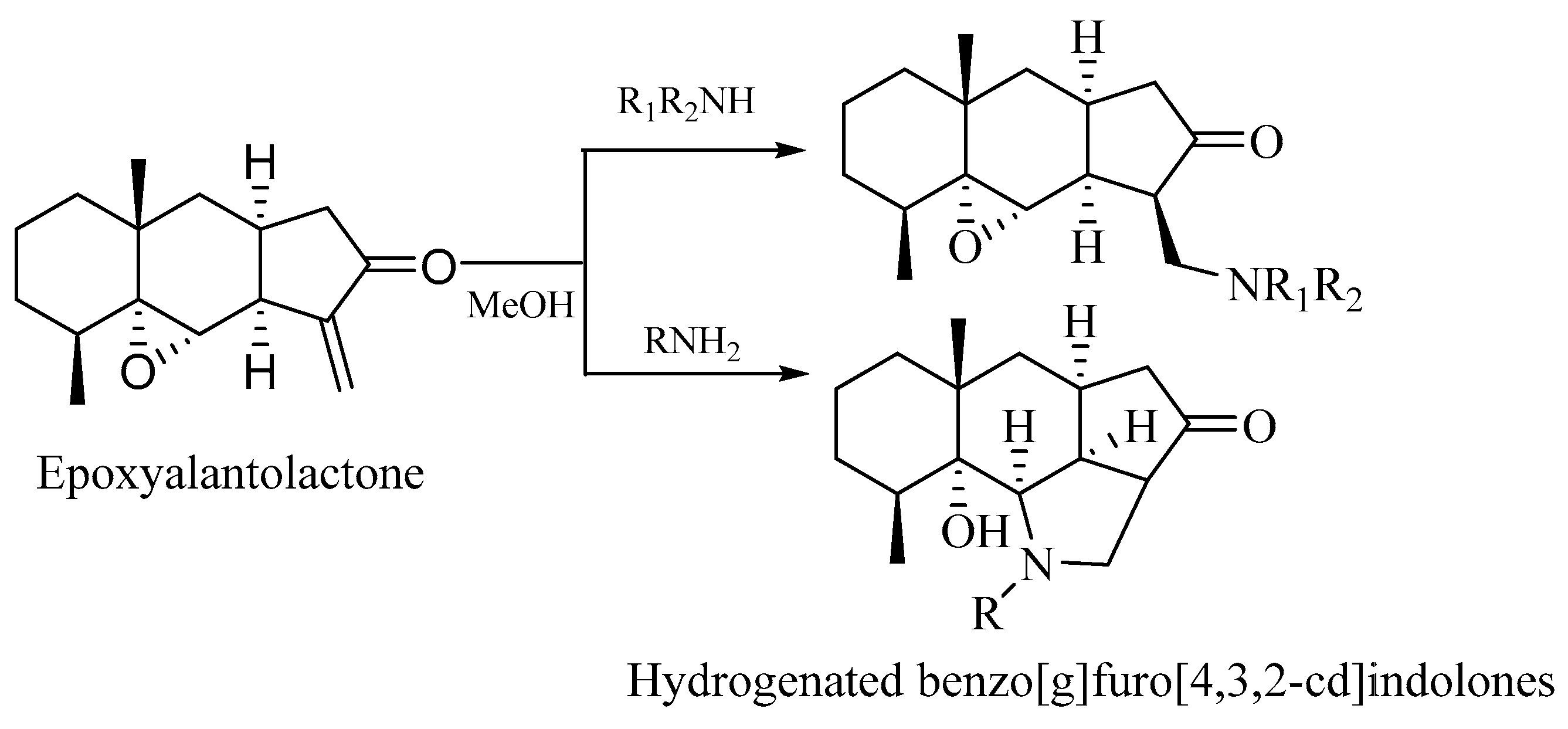

2.2. Chemistry

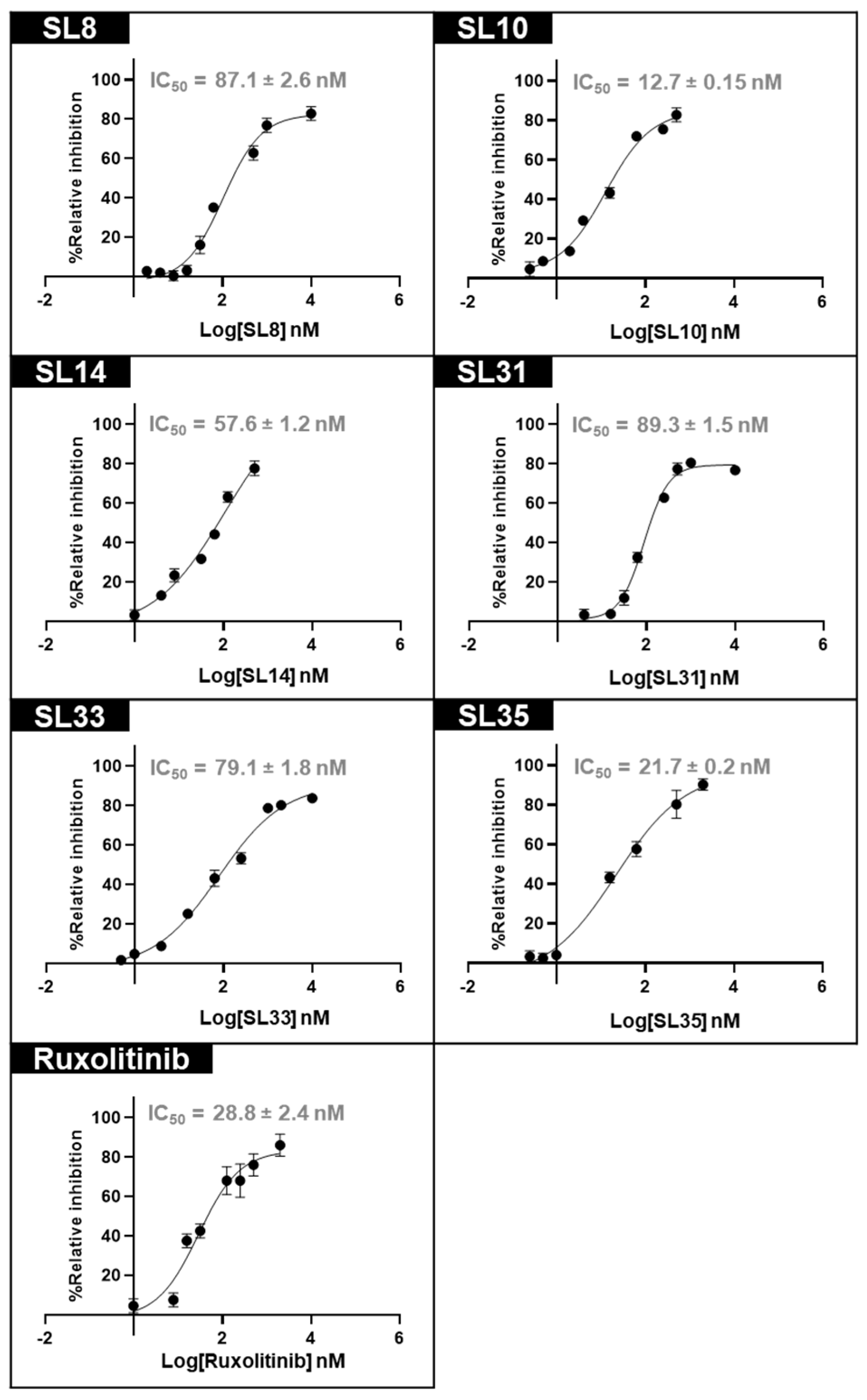

2.3. In Vitro Validation of JAK2 Inhibitory Activity

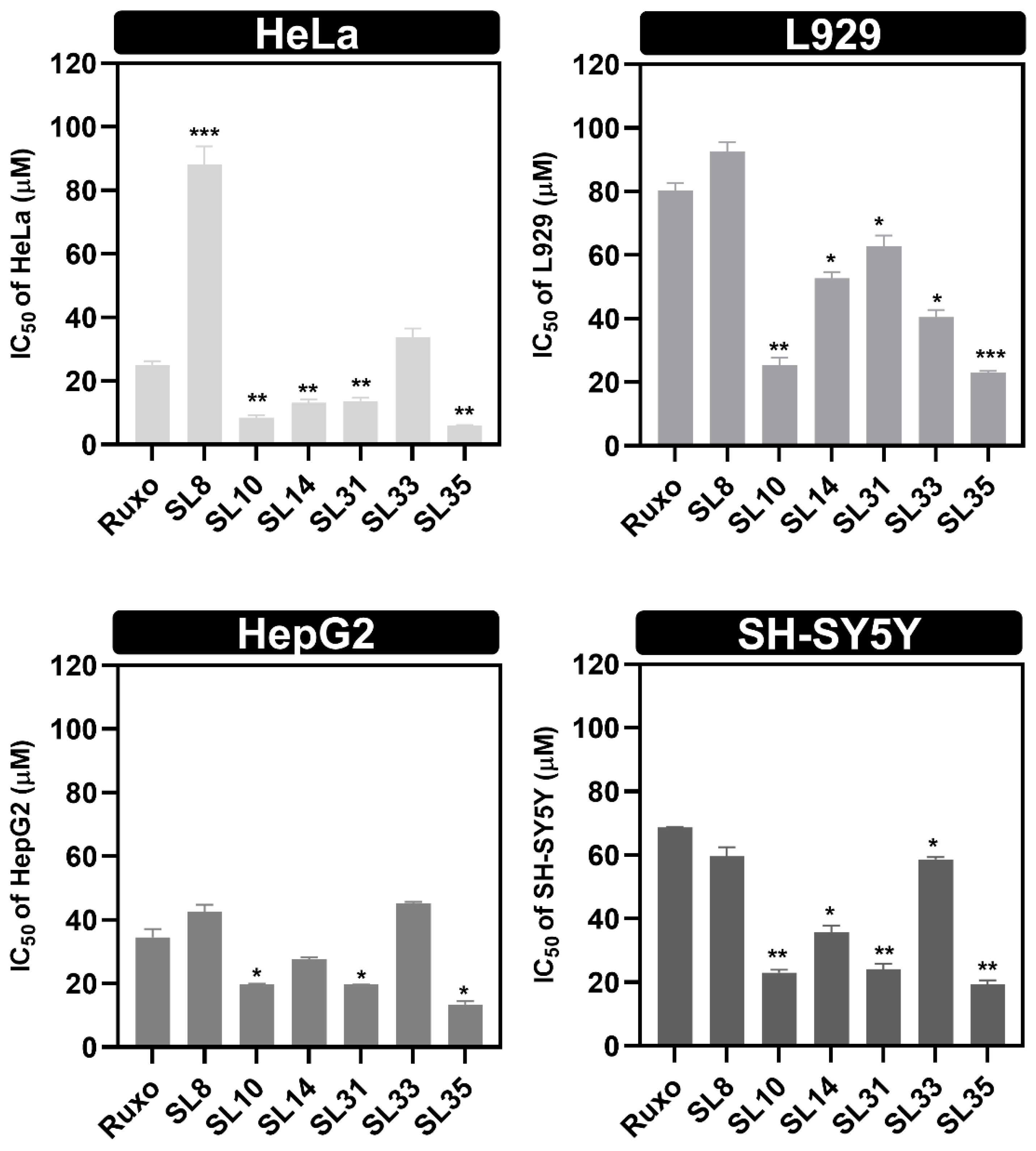

2.4. In Vitro Study of Anti-Proliferative Effects of SL Compounds

2.5. Evaluation of Apoptosis Induced by Lead Compounds in Cancer Cells

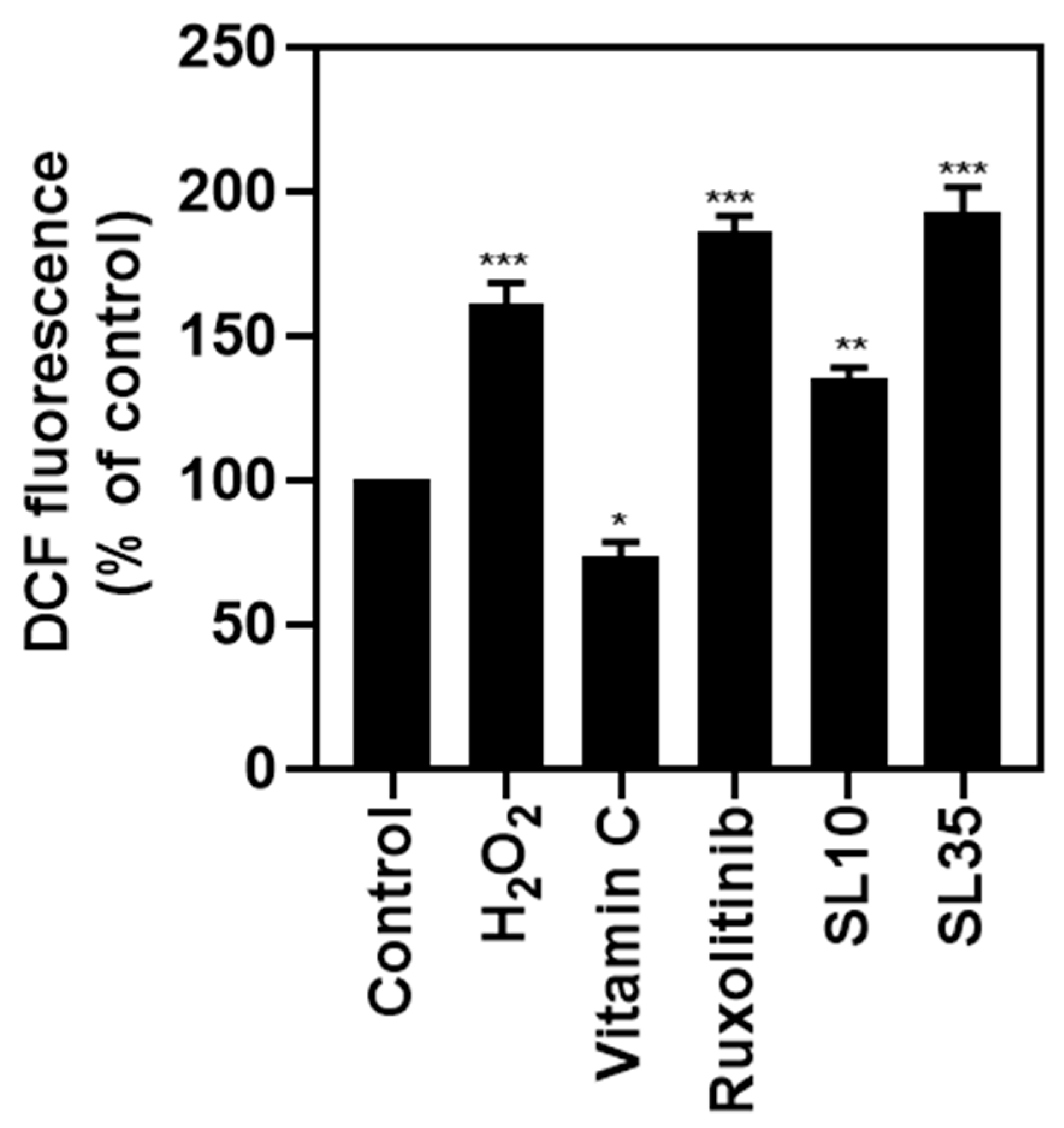

2.6. Investigation of Intracellular ROS Generation Induced by Lead Compounds

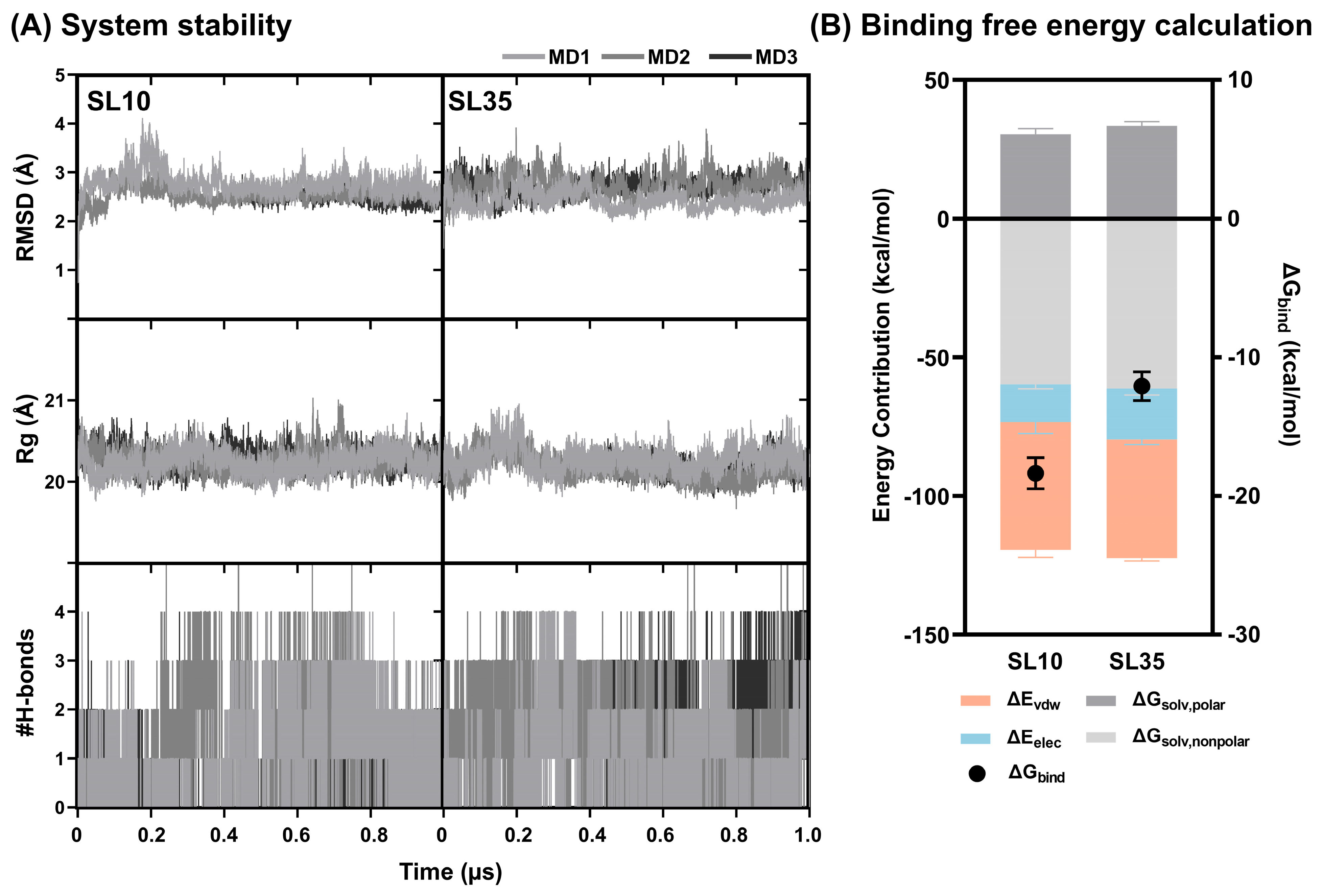

2.7. Structural Dynamics and Binding Free Energy Analysis of JAK2–SL Complexes

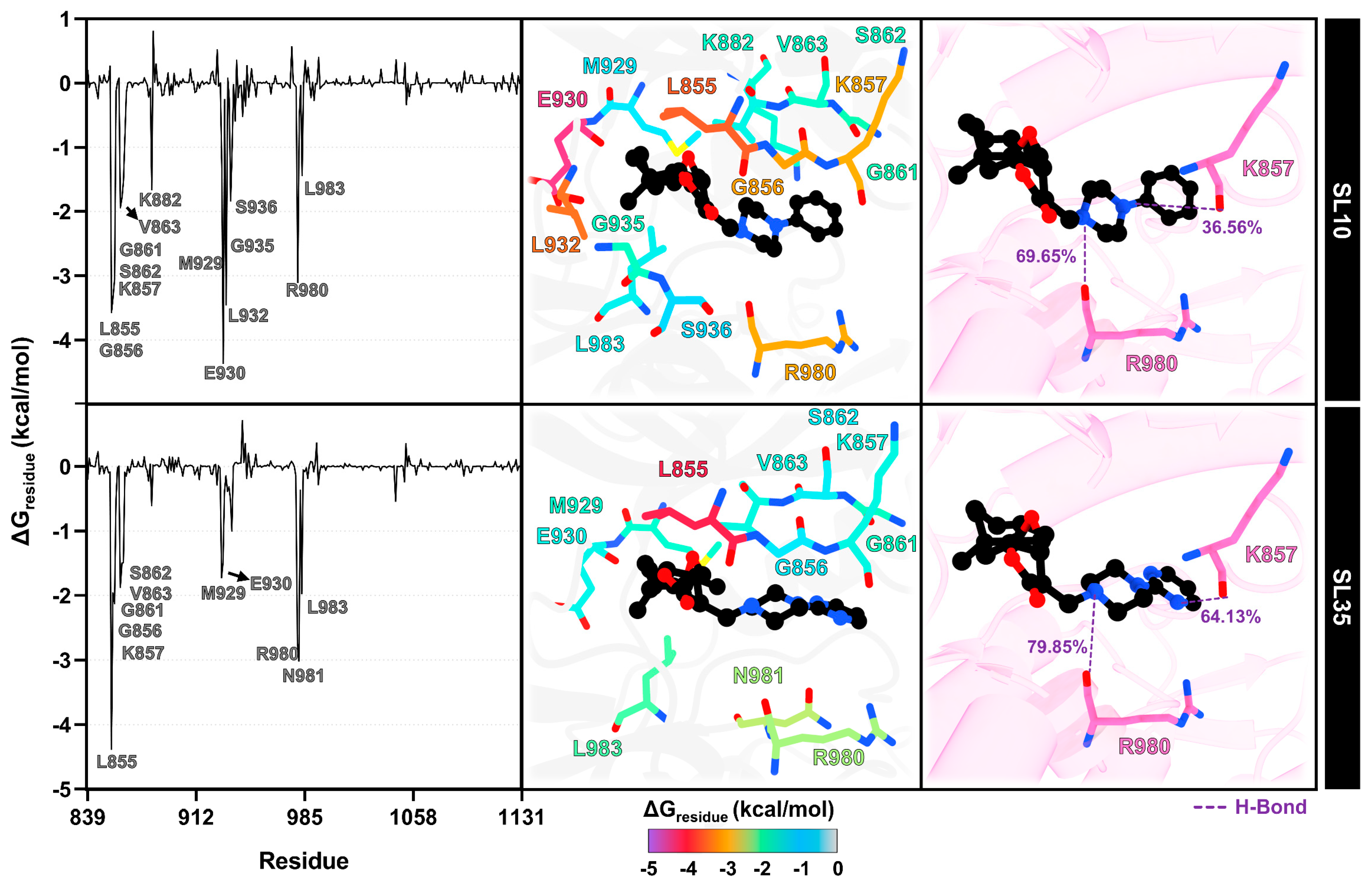

2.8. Interaction Profile of SL Derivatives as Potential JAK2 Inhibitors

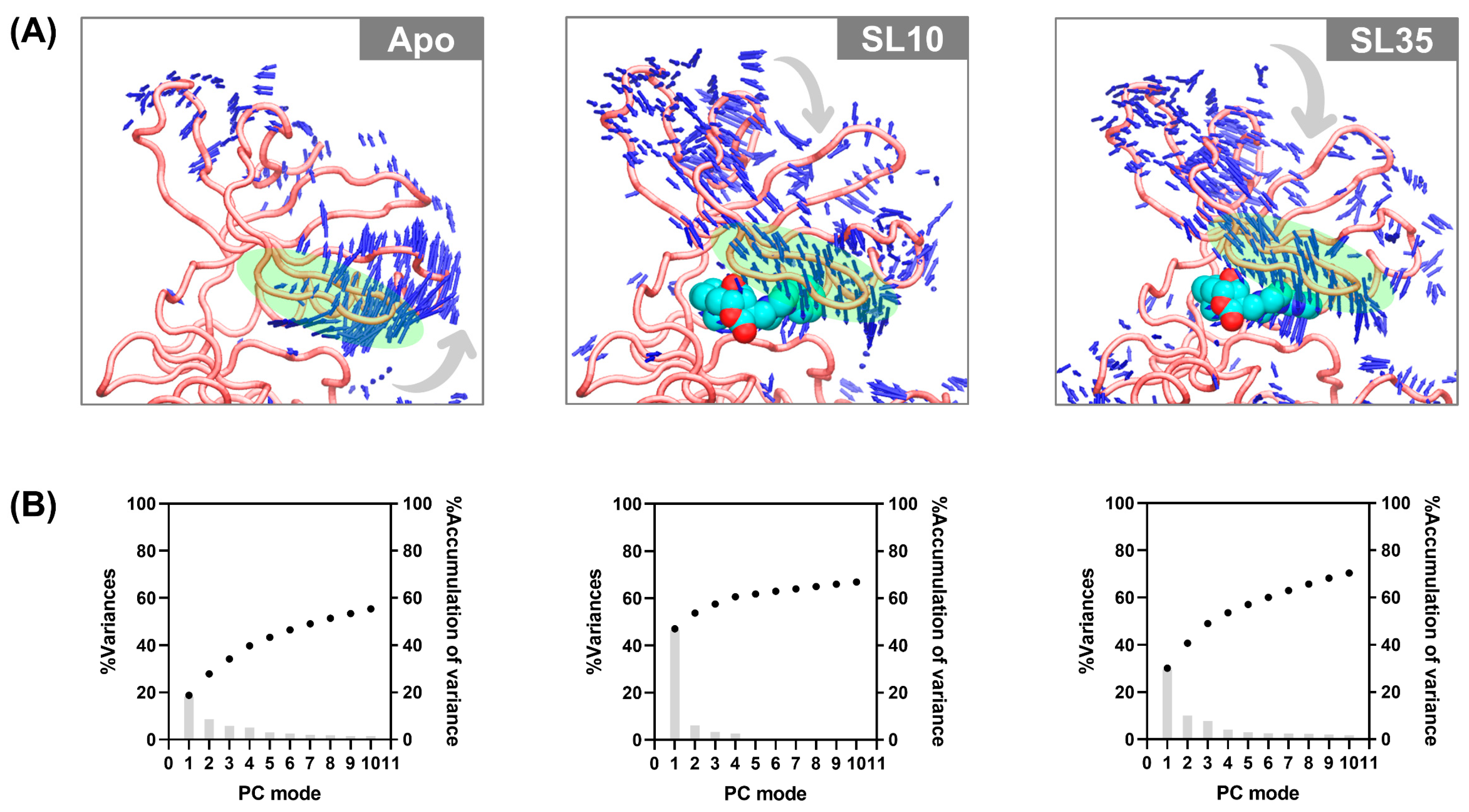

2.9. Conformational Dynamics of the JAK2 upon SL Binding

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Molecular Docking

3.2. Epoxidation of Alantolactone

3.3. Reaction of Epoxyalantolactone with Amines

3.4. Cell Lines, Chemicals and Reagents

3.5. JAK2 Kinase Assay

3.6. Cell Culture

3.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.8. Apoptosis Detection

3.9. DCFH2-DA Assay

3.10. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.11. Pharmacokinetic and Toxicological Evaluation

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guida, F.; Kidman, R.; Ferlay, J.; Schüz, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Kithaka, B.; Ginsburg, O.; Mailhot Vega, R.B.; Galukande, M.; Parham, G. Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2563–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, C.B.; Collins, S.I.; Young, L.S. The natural history of cervical HPV infection: Unresolved issues. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanjose, S.; Quint, W.G.; Alemany, L.; Geraets, D.T.; Klaustermeier, J.E.; Lloveras, B.; Tous, S.; Felix, A.; Bravo, L.E.; Shin, H.-R. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: A retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMay, R.M. Cytopathology of false negatives preceding cervical carcinoma. AJOG 1996, 175, 1110–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wentzensen, N.; Zhang, R.R.; Dunn, S.T.; Gold, M.A.; Wang, S.S.; Schiffman, M.; Walker, J.L.; Zuna, R.E. Factors associated with reduced accuracy in Papanicolaou tests for patients with invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014, 122, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Sings, H.; Bryan, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Mach, H.; Kosinski, M.; Washabaugh, M.; Sitrin, R.; Barr, E. GARDASIL®: Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccine development–from bench top to bed-side. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 81, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monie, A.; Hung, C.-F.; Roden, R.; Wu, T.C. Cervarix™: A vaccine for the prevention of HPV 16, 18-associated cervical cancer. Biol. Targets Ther. 2008, 2, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Tumban, E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antivir. Res. 2016, 130, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marth, C.; Landoni, F.; Mahner, S.; McCormack, M.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Colombo, N.; Committee, E.G. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv72–iv83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Herrero, E.; Fernández-Medarde, A. Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: Drug nanocarriers, the future of chemotherapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.K.; Cucchiella, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Li, J.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S.; Wei, G.; Zeng, X. Modelling the correlations of e-waste quantity with economic increase. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompaey, L.; Galien, R.; van der Aar, E.M.; Clement-Lacroix, P.; Nelles, L.; Smets, B.; Lepescheux, L.; Christophe, T.; Conrath, K.; Vandeghinste, N. Preclinical characterization of GLPG0634, a selective inhibitor of JAK1, for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, D.S.; Horvath, C.M. A road map for those who don’t know JAK-STAT. Science 2002, 296, 1653–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, J.S.; Rosler, K.M.; Harrison, D.A. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, J.J.; Holland, S.M.; Staudt, L.M. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, M.N.; Flaxman, S.R.; Boerma, T.; Vanderpoel, S.; Stevens, G.A. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Kambhampati, S.; Parmar, S.; Platanias, L.C. Jak family of kinases in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003, 22, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, E.J.; Scott, L.M.; Campbell, P.J.; East, C.; Fourouclas, N.; Swanton, S.; Vassiliou, G.S.; Bench, A.J.; Boyd, E.M.; Curtin, N. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet 2005, 365, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralovics, R.; Teo, S.-S.; Buser, A.S.; Brutsche, M.; Tiedt, R.; Tichelli, A.; Passamonti, F.; Pietra, D.; Cazzola, M.; Skoda, R.C. Altered gene expression in myeloproliferative disorders correlates with activation of signaling by the V617F mutation of Jak2. Blood 2005, 106, 3374–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, M.I.; Bacon, W.A.; Kapeni, C.; Fitch, S.R.; Kimber, G.; Cheng, S.P.; Li, J.; Green, A.R.; Ottersbach, K. Analysis of Jak2 signaling reveals resistance of mouse embryonic hematopoietic stem cells to myeloproliferative disease mutation. Blood 2016, 127, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchert, M.; Burns, C.; Ernst, M. Targeting JAK kinase in solid tumors: Emerging opportunities and challenges. Oncogene 2016, 35, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Biehl, A.; Gadina, M.; Hasni, S.; Schwartz, D.M. JAK–STAT signaling as a target for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases: Current and future prospects. Drugs 2017, 77, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.W.; Al-Fayoumi, S.; Ma, H.; Komrokji, R.S.; Mesa, R.; Verstovsek, S. Comprehensive kinase profile of pacritinib, a nonmyelosuppressive Janus kinase 2 inhibitor. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2016, 8, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-C.; Li, L.S.; Kopp, N.; Montero, J.; Chapuy, B.; Yoda, A.; Christie, A.L.; Liu, H.; Christodoulou, A.; van Bodegom, D. Activity of the type II JAK2 inhibitor CHZ868 in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Balligand, T.; Pecquet, C.; Mouton, C.; Colau, D.; Shiau, A.K.; Dusa, A.; Constantinescu, S.N. Differential effect of inhibitory strategies of the V617 mutant of JAK2 on cytokine receptor signaling. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Constantinescu, S.N. Rethinking JAK2 inhibition: Towards novel strategies of more specific and versatile janus kinase inhibition. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shi, M.; Shen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zuo, S.; Zuo, C.; Zhang, H.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, J. COX-1–derived thromboxane A2 plays an essential role in early B-cell development via regulation of JAK/STAT5 signaling in mouse. Blood 2014, 124, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, B.L.; Eckhardt, S.G.; Jimeno, A. JAK2 inhibition for the treatment of hematologic and solid malignancies. Expert Op. Investig. Drugs 2012, 21, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Lee, H.; Li, Y.-J.; Tripathi, S.C.; Yue, C.; Zhang, C.; Lifshitz, V.; Song, J.; Yuan, Y. JAK/STAT3-regulated fatty acid β-oxidation is critical for breast cancer stem cell self-renewal and chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 136–150.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.L.; Macdonald, A. JAK2 inhibition impairs proliferation and sensitises cervical cancer cells to cisplatin-induced cell death. Cancers 2019, 11, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Selenadiazole-Induced Hela Cell Apoptosis through the Redox Oxygen Species-Mediated JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 20919–20926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, N.C.; Sarma, J.C.; Barua, N.C.; Sarma, S.; Sharma, R.P. Germination and growth inhibitory sesquiterpene lactones and a flavone from Tithonia diversifolia. Phytochem 1994, 36, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoja, S.O.; Nnadi, C.O.; Udem, S.C.; Anaga, A.O. Potential antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of a heliangolide sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Helianthus annuus L. leaves. Acta Pharm. 2020, 70, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, M.; Shah, I.; Ali, N.; Adhikari, A.; Tahir, M.N.; Shah, S.W.A.; Ishtiaq, S.; Khan, J.; Khan, S.; Umer, M.N. Sesquiterpene lactone! A promising antioxidant, anticancer and moderate antinociceptive agent from Artemisia macrocephala jacquem. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Santos, E.; Vilas-Boas, D.F.; Diniz, L.F.; Veloso, M.P.; Mazzeti, A.L.; Rodrigues, M.R.; Oliveira, C.M.; Fernandes, V.H.C.; Novaes, R.D.; Chagas-Paula, D.A. Sesquiterpene lactone potentiates the immunomodulatory, antiparasitic and cardioprotective effects on anti-Trypanosoma cruzi specific chemotherapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 77, 105961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; Brás, T.; Santos, J.O.; Sampaio, P.; Gomes, A.C.; Duarte, M.F. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory action of sesquiterpene lactones. Molecules 2022, 27, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurella, L.C.; Mirakian, N.T.; Garcia, M.N.; Grasso, D.H.; Sülsen, V.P.; Papademetrio, D.L. Sesquiterpene lactones as promising candidates for cancer therapy: Focus on pancreatic cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhyani, P.; Sati, P.; Sharma, E.; Attri, D.C.; Bahukhandi, A.; Tynybekov, B.; Szopa, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D.; Suleria, H.A. Sesquiterpenoid lactones as potential anti-cancer agents: An update on molecular mechanisms and recent studies. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Roscetto, E.; Masi, M.; Tuzi, A.; Radjai, I.; Gahdab, C.; Paolillo, R.; Guarino, A.; Catania, M.R.; Evidente, A. Sesquiterpene lactones from Cotula cinerea with antibiotic activity against clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Y.; Yang, W.-Q.; Zhou, X.-Z.; Shao, F.; Shen, T.; Guan, H.-Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L.-M. Antibacterial and antifungal sesquiterpenoids: Chemistry, resource, and activity. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.S.; Anastácio, J.D.; Nunes dos Santos, C. Sesquiterpene lactones: Promising natural compounds to fight inflammation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sülsen, V.P.; Elso, O.G.; Borgo, J.; Laurella, L.C.; Catalán, C.A. Recent patents on sesquiterpene lactones with therapeutic application. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2021, 69, 129–194. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; He, J.; Huang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Antiviral activity of the sesquiterpene lactones from Centipeda minima against influenza A virus in vitro. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801300201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, Y.; Abdelwahab, G.; Heraiz, A.A.; Sallam, M.; Othman, A. Exploring sesquiterpene lactones: Structural diversity and antiviral therapeutic insights. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1970–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althurwi, H.N.; Soliman, G.A.; Abdel-Rahman, R.F.; Abd-Elsalam, R.M.; Ogaly, H.A.; Alqarni, M.H.; Albaqami, F.F.; Abdel-Kader, M.S. Vulgarin, a Sesquiterpene Lactone from Artemisia judaica, improves the antidiabetic effectiveness of Glibenclamide in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic rats via modulation of PEPCK and G6Pase genes expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.P.; Borges, B.A.; Veloso, M.P.; Chagas-Paula, D.A.; Goncalves, R.V.; Novaes, R.D. Impact of sesquiterpene lactones on the skin and skin-related cells? A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo evidence. Life Sci. 2021, 265, 118815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fateh, S.T.; Fateh, S.T.; Shekari, F.; Mahdavi, M.; Aref, A.R.; Salehi-Najafabadi, A. The effects of sesquiterpene lactones on the differentiation of human or animal cells cultured in-vitro: A critical systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 862446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeratichamroen, S.; Lirdprapamongkol, K.; Thongnest, S.; Boonsombat, J.; Chawengrum, P.; Sornprachum, T.; Sirirak, J.; Verathamjamras, C.; Ornnork, N.; Ruchirawat, S. JAK2/STAT3-mediated dose-dependent cytostatic and cytotoxic effects of sesquiterpene lactones from Gymnanthemum extensum on A549 human lung carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukhov, S.; Afanasyeva, S.; Anikina, L.; Semakov, A.; Dubrovskaya, E.; Klochkov, S. Amino derivatives of natural epoxyalantolactone: Synthesis and cytotoxicity toward tumor cells. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 44, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patigo, A.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Cao, V.; Paunrat, W.; Vijara, N.; Chokmahasarn, T.; Maitarad, P.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Shigeta, Y.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S.; et al. Design, synthesis, in vitro, in silico, and SAR studies of flavone analogs towards anti-dengue activity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengphasatporn, K.; Shigeta, Y. Advances in Methods and Applications of Quantum Systems in Chemistry, Physics, and Biology. In Integrated In-Silico Drug Modeling for Viral Proteins; Grabowski, I., Słowik, K., Maruani, J., Brändas, E.J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Sanachai, K.; Aiebchun, T.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Seetaha, S.; Tabtimmai, L.; Maitarad, P.; Xenikakis, I.; Geronikaki, A.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Discovery of novel JAK2 and EGFR inhibitors from a series of thiazole-based chalcone derivatives. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalapbutr, P.; Sangkhawasi, M.; Kammarabutr, J.; Chamni, S.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Rosmarinic Acid as a Potent Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitor: In Vitro and In Silico Study. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2046–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengphasatporn, K.; Wilasluck, P.; Deetanya, P.; Wangkanont, K.; Chavasiri, W.; Visitchanakun, P.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Paunrat, W.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; et al. Halogenated Baicalein as a Promising Antiviral Agent toward SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, J.D.; McCammon, J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangpheak, K.; Tabtimmai, L.; Seetaha, S.; Rungnim, C.; Chavasiri, W.; Wolschann, P.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Biological Evaluation and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Chalcone Derivatives as Epidermal Growth Factor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2019, 24, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucl. Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wielheesen, D.; Sillevis Smitt, P.; Haveman, J.; Fatehi, D.; Van Rhoon, G.; Van Der Zee, J. Incidence of acute peripheral neurotoxicity after deep regional hyperthermia of the pelvis. Int. J. Hyperth. 2008, 24, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, C.; Azzi, R.; Wagner, D. The development of the globally harmonized system (GHS) of classification and labelling of hazardous chemicals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 125, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, N.J.; McGown, A.T.; Nduka, J.; Hadfield, J.A.; Pritchard, R.G. Cytotoxic michael-type amine adducts of α-methylene lactones alantolactone and isoalantolactone. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.-R.; Wu, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-W.; Lien, T.-W.; Chen, W.-C.; Tan, U.-K.; Hsu, J.T.; Hsieh, H.-P. Synthesis and anti-viral activity of a series of sesquiterpene lactones and analogues in the subgenomic HCV replicon system. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, C.L.; Pridgeon, J.W.; Fronczek, F.R.; Becnel, J.J. Structure–activity relationship studies on derivatives of eudesmanolides from Inula helenium as toxicants against Aedes aegypti larvae and adults. Chem. Biodiver. 2010, 7, 1681–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.R.; Mo, H.; Bieberich, A.A.; Alavanja, T.; Colby, D.A. Amino-derivatives of the sesquiterpene lactone class of natural products as prodrugs. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klochkov, S.; Afanaseva, S.; Pushin, A. Acidic isomerization of alantolactone derivatives. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2006, 42, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyyasov, A.; Seitembetov, T.; Turdybekov, K.; Adekenov, S. Epoxidation of alantolactone and isoalantolactone. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1996, 32, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, T.; Xu, L.; Dong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, Y.; Chen, K.; Qin, M.; Liu, Y. Discovery of 4-piperazinyl-2-aminopyrimidine derivatives as dual inhibitors of JAK2 and FLT3. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, J.; Lu, J.; Ran, D.; Gan, Z. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 2, 4-dianilinopyrimidine derivatives as potent dual janus kinase 2 and histone deacetylases inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1253, 132200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hu, M.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, M.; Tang, M.; Qi, W.; Shi, M.; He, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, C. N-(pyrimidin-2-yl)-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-amine derivatives as selective janus kinase 2 inhibitors for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14921–14936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, B.; Gor, R.; Ramalingam, S.; Thiagarajan, A.; Sohn, H.; Madhavan, T. Repurposing FDA-approved compounds to target JAK2 for colon cancer treatment. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Nagarajan, S.K.; Sathish, S.; Negi, V.S.; Sohn, H.; Madhavan, T. Identification of potent and selective JAK1 lead compounds through ligand-based drug design approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 837369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, B.; Sohn, H.; Madhavan, T. Discovery of potential JAK2 inhibitor: In silico molecular docking and molecular dynamics study for colon cancer therapy. Chem. Pap. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, J.; Mughal, T.I.; Verstovsek, S. Biology and clinical management of myeloproliferative neoplasms and development of the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 4399–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, Y.-T.; Lau, W.K.-W.; Yu, M.-S.; Lai, C.S.-W.; Yeung, S.-C.; So, K.-F.; Chang, R.C.-C. Effects of all-trans-retinoic acid on human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma as in vitro model in neurotoxicity research. Neurotoxico 2009, 30, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palachai, N.; Buranrat, B.; Noisa, P.; Mairuae, N. Oroxylum indicum (L.) Leaf Extract Attenuates β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowati, W.; Laksmitawati, D.R.; Pratami, D.K.; Rahmat, D.; Kiran, S.R.; Devi, J.A.; Priyandoko, D.; Dewi, N.S.M.; Sutendi, A.F.; Azis, R. Protective effects of turmeric extract, curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, bis-demethoxycurcumin, and ar-turmerone from Curcuma longa L. rhizomes on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Asian Pac. J. Trop.Biomed. 2025, 15, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, L.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; Pérez-Cataldo, G.; Castell, J.V.; Donato, M.T. HepG2 cells simultaneously expressing five P450 enzymes for the screening of hepatotoxicity: Identification of bioactivable drugs and the potential mechanism of toxicity involved. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hayashida, Y.; Kakehi, Y.; Tamura, H. Induction of G2/M arrest and apoptosis through mitochondria pathway by a dimer sesquiterpene lactone from Smallanthus sonchifolius in HeLa cells. JFDA 2017, 25, 619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, D.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J. Targeting thioredoxin reductase by parthenolide contributes to inducing apoptosis of HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 10021–10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. BBA Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Niu, J.; Luo, M.; Gou, Y.; Miao, L.; Zou, Z.; Cheng, Y. Induction of ROS overload by alantolactone prompts oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Shao, Z. Ambrosin exerts strong anticancer effects on human breast cancer cells via activation of caspase and inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.Z.; Nisar, M.A.; Alshwmi, M.; Din, S.R.U.; Gamallat, Y.; Khan, M.; Ma, T. Brevilin A inhibits STAT3 signaling and induces ROS-dependent apoptosis, mitochondrial stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadlou, H.; Hamzeloo-Moghadam, M.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Yami, A.; Gharehbaghian, A. Britannin, a sesquiterpene lactone induces ROS-dependent apoptosis in NALM-6, REH, and JURKAT cell lines and produces a synergistic effect with vincristine. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6249–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Tang, B.; Qiu, B. Growth inhibition of Saos-2 osteosarcoma cells by lactucopicrin is mediated via inhibition of cell migration and invasion, sub-G1 cell cycle disruption, apoptosis induction and Raf signalling pathway. J. Buon 2019, 24, 2136–2140. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, R.; Von Schwarzenberg, K.; López-Antón, N.; Rudy, A.; Wanner, G.; Dirsch, V.M.; Vollmar, A.M. Helenalin bypasses Bcl-2-mediated cell death resistance by inhibiting NF-κB and promoting reactive oxygen species generation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, R.F.; Schapira, M. A systematic analysis of atomic protein–ligand interactions in the PDB. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanachai, K.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Tabtimmai, L.; Seetaha, S.; Kittikool, T.; Yotphan, S.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Discovery of JAK2/3 inhibitors from quinoxalinone-containing compounds. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33587–33598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Shen, P.; Wang, H.; Qin, L.; Ren, J.; Sun, Q.; Ge, R.; Bian, J.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Z. Discovery of imidazopyrrolopyridines derivatives as novel and selective inhibitors of JAK2. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 218, 113394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Lim-Wilby, M. Molecular docking. In Molecular Modeling of Proteins; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.K.; Bamert, R.S.; Patel, O.; Wang, C.; Walden, P.M.; Wilks, A.F.; Fantino, E.; Rossjohn, J.; Lucet, I.S. Dissecting specificity in the Janus kinases: The structures of JAK-specific inhibitors complexed to the JAK1 and JAK2 protein tyrosine kinase domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 387, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.R.; Li, B.; Yun, S.Y.; Chan, A.; Nareddy, P.; Gunawan, S.; Ayaz, M.; Lawrence, H.R.; Reuther, G.W.; Lawrence, N.J. Structural insights into JAK2 inhibition by ruxolitinib, fedratinib, and derivatives thereof. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 2228–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Virtanen, A.; Zmajkovic, J.; Hilpert, M.; Skoda, R.C.; Silvennoinen, O.; Haikarainen, T. Functional and structural characterization of clinical-stage janus kinase 2 inhibitors identifies determinants for drug selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 10012–10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T.; Kearney, P.C.; Kim, B.G.; Johnson, H.W.; Aay, N.; Arcalas, A.; Brown, D.S.; Chan, V.; Chen, J.; Du, H. SAR and in vivo evaluation of 4-aryl-2-aminoalkylpyrimidines as potent and selective Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7653–7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetiyo, A.; Kumala, S.; Mumpuni, E.; Tjandrawinata, R.R. Validation of structural-based virtual screening protocols with the PDB CODE 3G0B and prediction of the activity of tinospora crispacompounds as inhibitors of dipeptidyl-peptidase-IV. Res. Results Pharmacol. 2022, 8, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.C.; Murray, C.W.; Nissink, J.W.M.; Taylor, R.D.; Taylor, R. Comparing protein–ligand docking programs is difficult. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2005, 60, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolinsky, T.J.; Czodrowski, P.; Li, H.; Nielsen, J.E.; Jensen, J.H.; Klebe, G.; Baker, N.A. PDB2PQR: Expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W522–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvin was Used for Drawing, Displaying and Characterizing Chemical Structures, Substructures and Reactions, Marvin, ChemAxon. Available online: https://www.chemaxon.com (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaussian, I. Gaussian 16 Revision C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Todsaporn, D.; Zubenko, A.; Kartsev, V.; Aiebchun, T.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Petrou, A.; Geronikaki, A.; Divaeva, L.; Chekrisheva, V.; Yildiz, I. Discovery of novel EGFR inhibitor targeting wild-type and mutant forms of EGFR: In silico and in vitro study. Molecules 2023, 28, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todsaporn, D.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Poo-Arporn, R.P.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Structural dynamics and kinase inhibitory activity of three generations of tyrosine kinase inhibitors against wild-type, L858R/T790M, and L858R/T790M/C797S forms of EGFR. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 147, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegzouti, H.; Zdanovskaia, M.; Hsiao, K.; Goueli, S.A. ADP-Glo: A Bioluminescent and homogeneous ADP monitoring assay for kinases. Assay. Drug Dev. Technol. 2009, 7, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riss, T.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Niles, A.L.; Duellman, S.; Benink, H.A.; Worzella, T.J.; Minor, L. Cell viability assays. Assay Guid. Man. 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144065 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Rieger, A.M.; Nelson, K.L.; Konowalchuk, J.D.; Barreda, D.R. Modified annexin V/propidium iodide apoptosis assay for accurate assessment of cell death. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 50, 2597. [Google Scholar]

- Ciapetti, G.; Granchi, D.; Verri, E.; Savarino, L.; Cenni, E.; Savioli, F.; Pizzoferrato, A. Fluorescent microplate assay for respiratory burst of PMNs challenged in vitro with orthopedic metals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 41, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotz, A.W.; Williamson, M.J.; Xu, D.; Poole, D.; Le Grand, S.; Walker, R.C. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 1. Generalized born. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2012, 8, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, R.; Jerath, K.; Badkar, A.V.; Kalonia, D.S. Long-and short-range electrostatic interactions affect the rheology of highly concentrated antibody solutions. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, H.J.; Postma, J.V.; Van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.R.; Cheatham, T.E., III. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 3084–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.R., III; McGee, T.D., Jr.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA. py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Drug-Likeness Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW a | HBD b | HBA c | RB d | PSAe | LogP f | Lipinski g | |

| SL8 | 415.52 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 69.32 | 3.45 | accept |

| SL10 | 410.55 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 45.31 | 3.38 | accept |

| SL14 | 428.54 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 45.31 | 3.71 | accept |

| SL31 | 424.58 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 45.31 | 3.72 | accept |

| SL33 | 408.53 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 66.65 | 3.99 | accept |

| SL35 | 412.53 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 71.09 | 2.33 | accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Todsaporn, D.; Sanachai, K.; Aonbangkhen, C.; Poo-arporn, R.P.; Kartsev, V.; Pukhov, S.; Afanasyeva, S.; Geronikaki, A.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Identification of Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from Amino Derivatives of Epoxyalantolactone: In Silico and In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010329

Todsaporn D, Sanachai K, Aonbangkhen C, Poo-arporn RP, Kartsev V, Pukhov S, Afanasyeva S, Geronikaki A, Rungrotmongkol T. Identification of Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from Amino Derivatives of Epoxyalantolactone: In Silico and In Vitro Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010329

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodsaporn, Duangjai, Kamonpan Sanachai, Chanat Aonbangkhen, Rungtiva P. Poo-arporn, Victor Kartsev, Sergey Pukhov, Svetlana Afanasyeva, Athina Geronikaki, and Thanyada Rungrotmongkol. 2026. "Identification of Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from Amino Derivatives of Epoxyalantolactone: In Silico and In Vitro Studies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010329

APA StyleTodsaporn, D., Sanachai, K., Aonbangkhen, C., Poo-arporn, R. P., Kartsev, V., Pukhov, S., Afanasyeva, S., Geronikaki, A., & Rungrotmongkol, T. (2026). Identification of Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from Amino Derivatives of Epoxyalantolactone: In Silico and In Vitro Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010329