Serum Oncostatin M in Ulcerative Colitis Patients and Its Relation to Disease Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

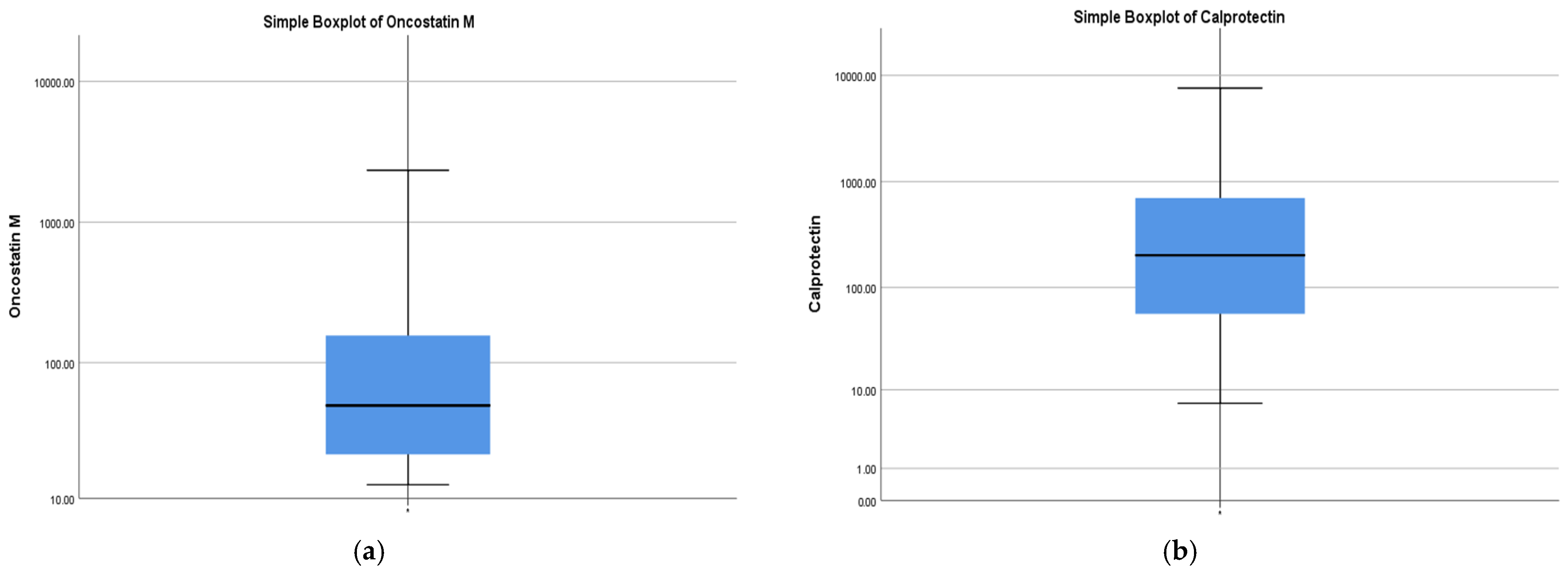

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

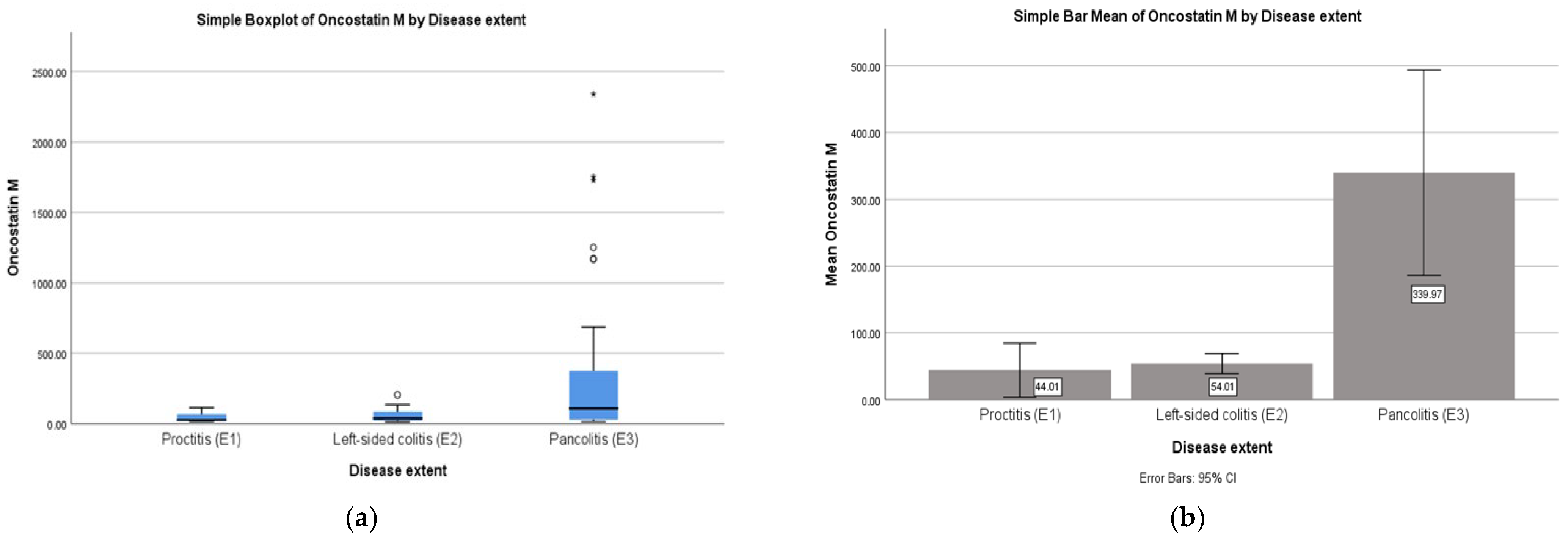

2.2. Correlations: OSM with Disease Extent

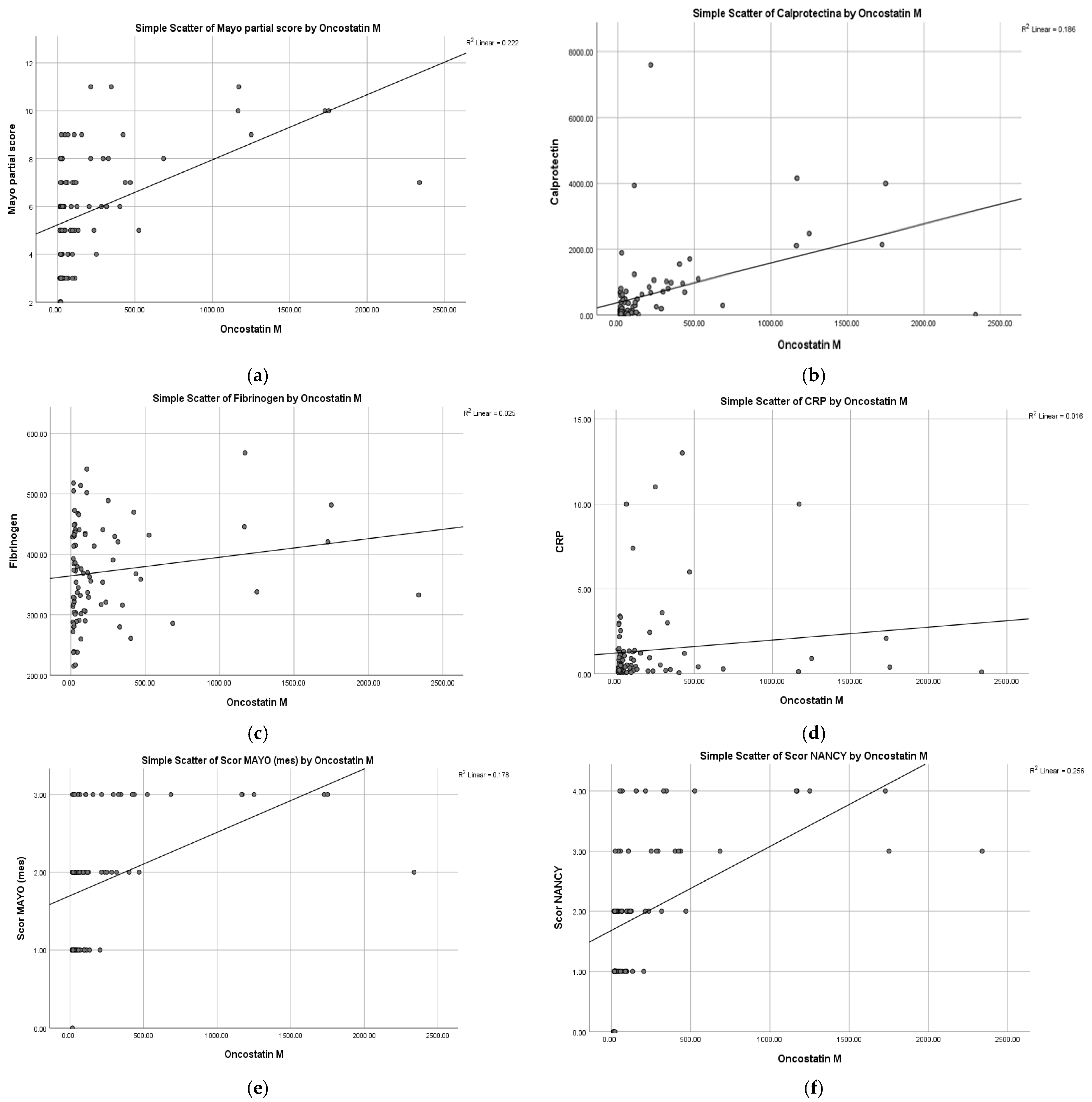

2.3. Correlations of OSM with Clinical Activity (pMS)

Partial Mayo Score

2.4. Correlations of OSM with Biological Markers (FC, CRP, Fibrinogen)

2.4.1. Fecal Calprotectin

2.4.2. CRP, Fibrinogen

2.4.3. Multiple Linear Regression

2.5. Correlations of OSM with Endoscopic Activity

2.6. Correlations of OSM with Histological Activity

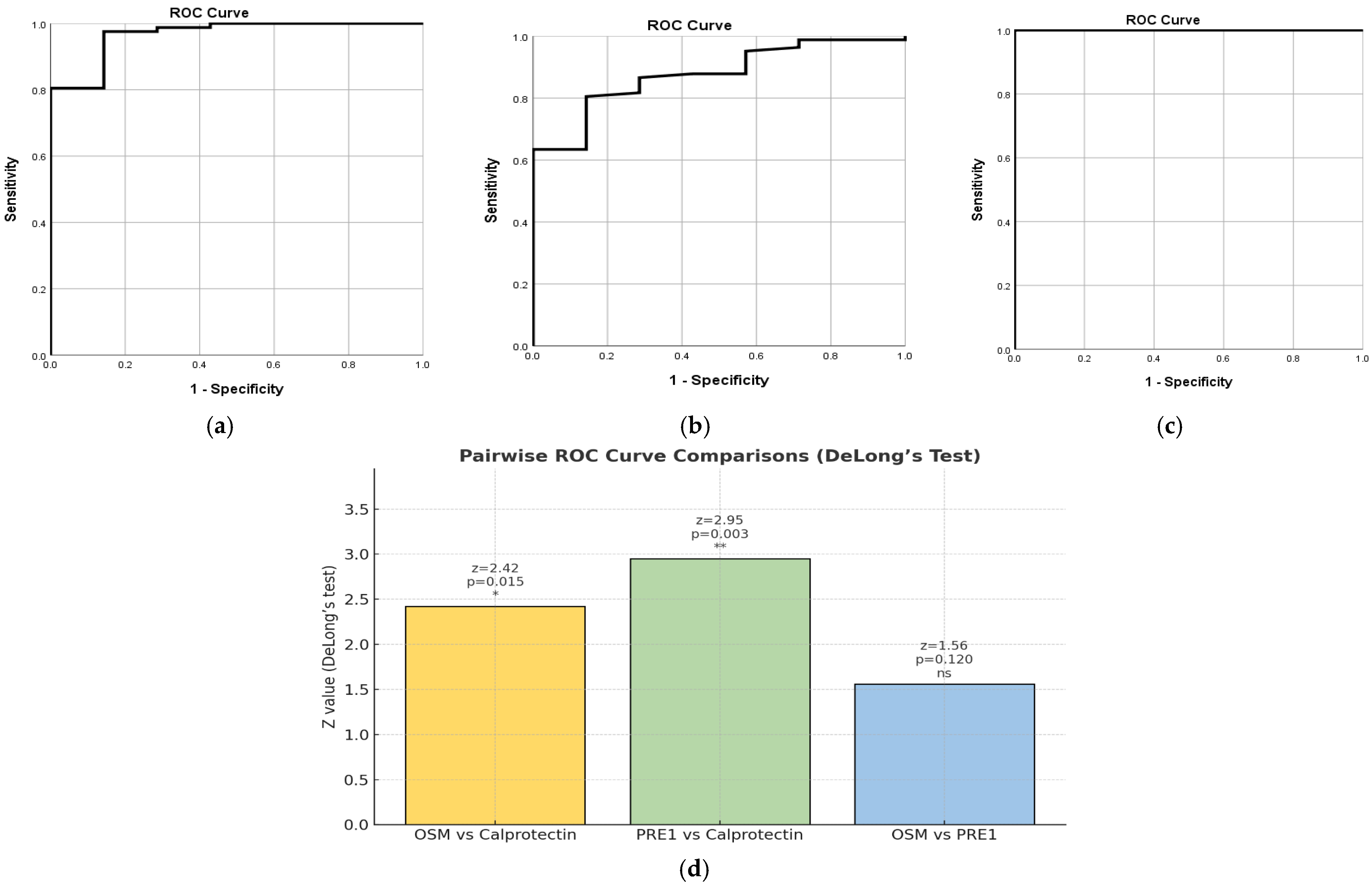

2.7. Combined Biomarkers

2.7.1. PRE1 Based on NHI

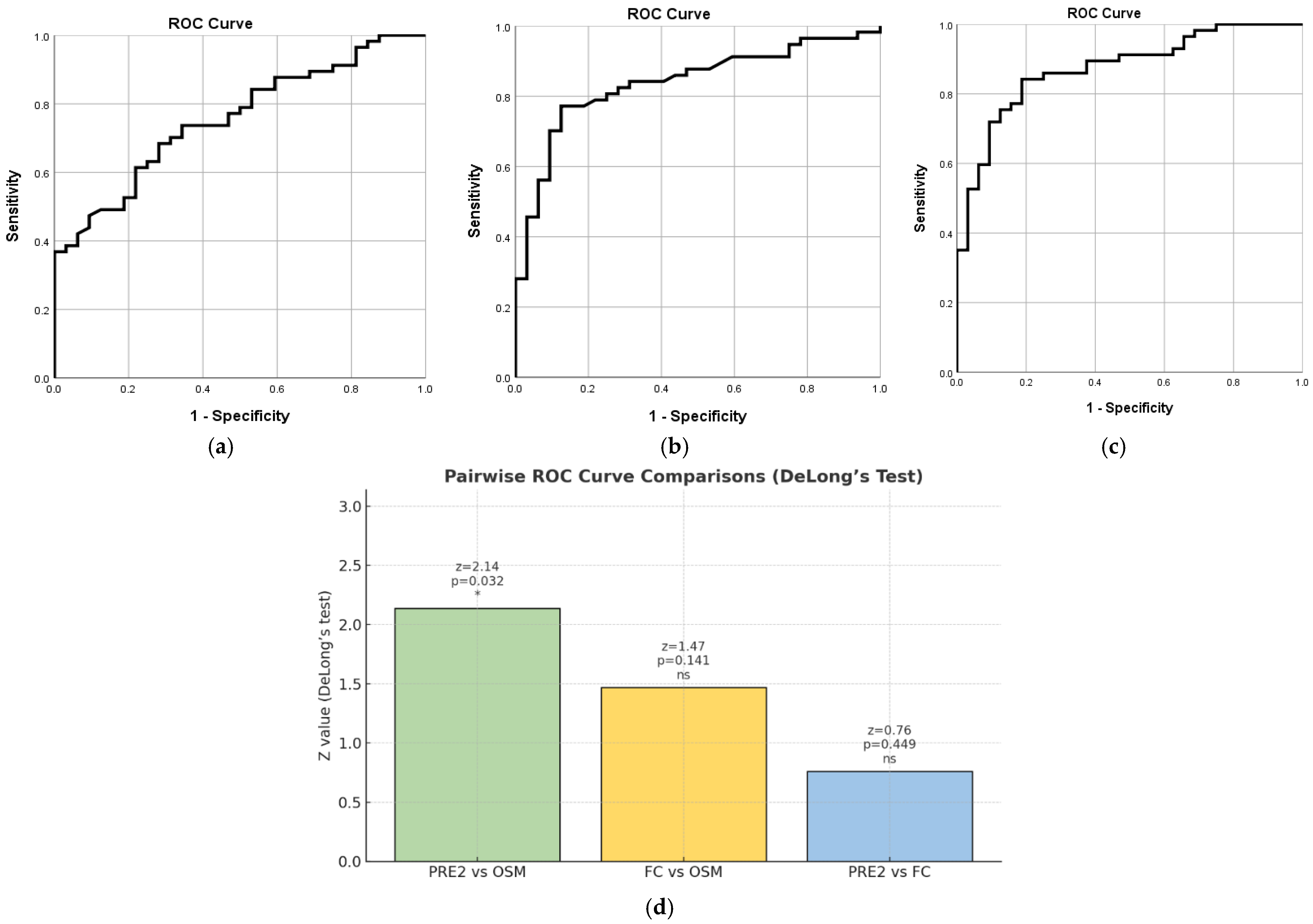

2.7.2. PRE2 Based on MES

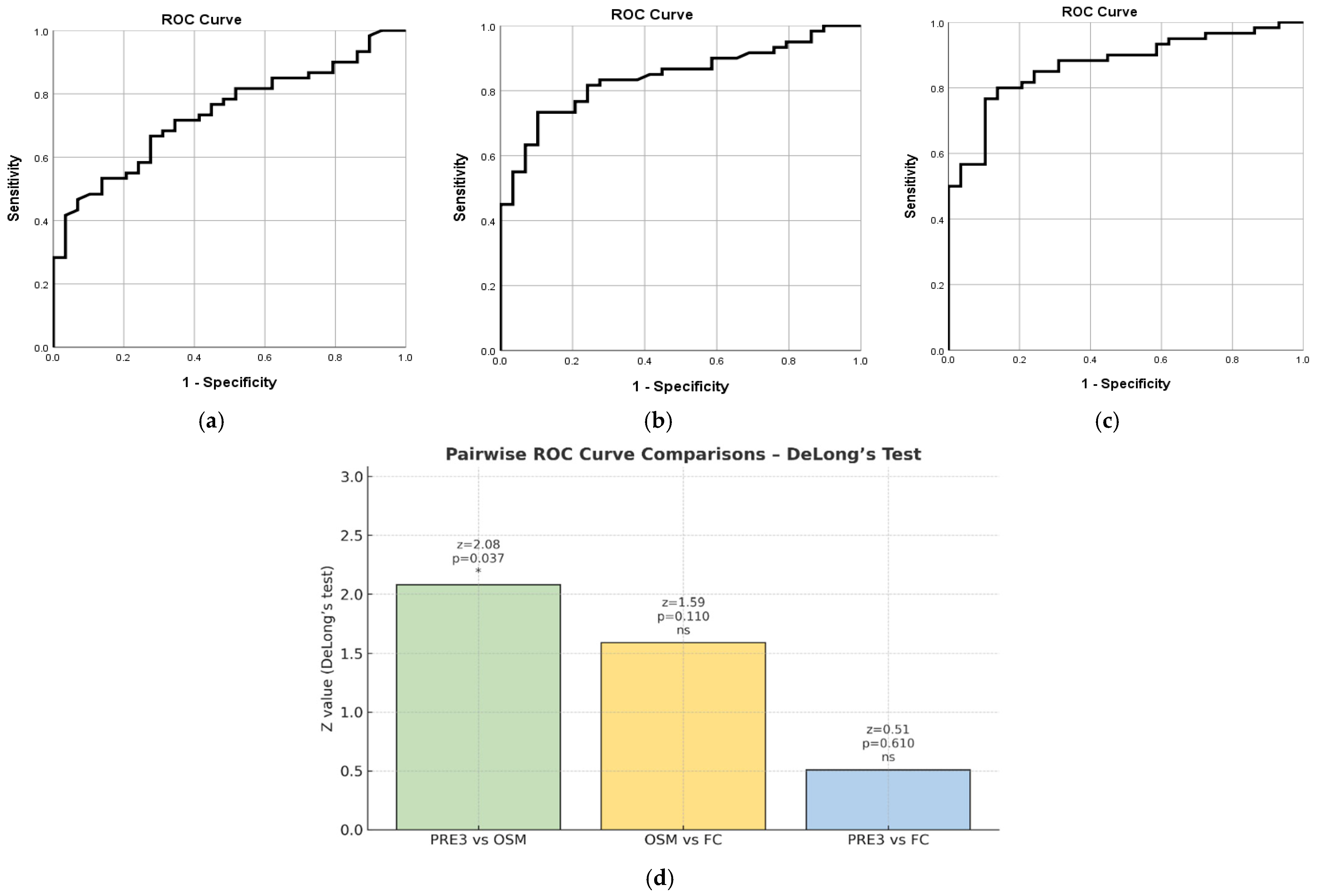

2.7.3. PRE3 Based on pMS

3. Discussion

3.1. Serum OSM Correlates with Disease Healing in UC

3.2. Study Limitations

3.3. Clinical Implications

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Considerations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feakins, R.; Borralho Nunes, P.; Driessen, A.; Gordon, I.O.; Zidar, N.; Baldin, P.; Christensen, B.; Danese, S.; Herlihy, N.; Iacucci, M.; et al. Definitions of Histological Abnormalities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An ECCO Position Paper. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kokkotis, G.; Filidou, E.; Tarapatzi, G.; Spathakis, M.; Kandilogiannakis, L.; Dovrolis, N.; Arvanitidis, K.; Drygiannakis, I.; Valatas, V.; Vradelis, S.; et al. Oncostatin M Induces a Pro-inflammatory Phenotype in Intestinal Subepithelial Myofibroblasts. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lee, C.; Yu, Z.; Chen, C.; Liang, C. Ulcerative colitis: Molecular insights and intervention therapy. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilescu, O.; Prelipcean, C.C.; Dranga, M.; Popa, I.V.; Mihai, C. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Quality of Life of IBD Patients. Medicina 2022, 58, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaros, K.; Adam, S.; Krokidis, M.G.; Exarchos, T.; Vlamos, P.; Vrahatis, A.G. Non-Invasive Biomarkers in the Era of Big Data and Machine Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H. IBD: Oncostatin M promotes inflammation in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestrovic, A.; Perkovic, N.; Bozic, D.; Kumric, M.; Vilovic, M.; Bozic, J. Precision Medicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Spotlight on Emerging Molecular Biomarkers. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, J.K.; Kalla, R.; Satsangi, J. Current and emerging biomarkers for ulcerative colitis. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 23, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Kim, M.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, E.R.; Hong, S.N.; Chang, D.K.; Ha, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-H. Histologic improvement predicts endoscopic remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, M.; Takahashi, F.; Tominaga, K.; Abe, K.; Izawa, N.; Fukushi, K.; Nagashima, K.; Kanamori, A.; Takenaka, K.; Sugaya, T.; et al. Relationship between endoscopic mucosal healing and histologic inflammation during remission maintenance phase in ulcerative colitis: A retrospective study. Endosc. Int. Open 2019, 7, E568–E575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Rocha, C.; Nayeri, S.; Turpin, W.; Steel, M.; Borowski, K.; Stempak, J.M.; Conner, J.; Silverberg, M.S. Combined Histo-endoscopic Remission but not Endoscopic Healing Alone in Ulcerative Colitis is Associated with a Mucosal Transcriptional Profile Resembling Healthy Mucosa. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, M. Current Use of Fecal Calprotectin in the Management of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 16, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, C.L.; Pruett, C.; Lighter, D.; Jorcyk, C.L. The clinical relevance of OSM in inflammatory diseases: A comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1239732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Ross, C.; Chande, N.; Gregor, J.; Ponich, T.; Khanna, R.; Sey, M.; Beaton, M.; Yan, B.; Kim, R.B.; et al. High oncostatin M predicts lack of clinical remission for patients with inflammatory bowel disease on tumor necrosis factor α antagonists. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertani, L.; Barberio, B.; Fornili, M.; Antonioli, L.; Zanzi, F.; Casadei, C.; Benvenuti, L.; Facchin, S.; D’ANtongiovanni, V.; Lorenzon, G.; et al. Serum oncostatin M predicts mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases treated with anti-TNF, but not vedolizumab. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Yu, Q.; Hu, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, P.; Ping, Y.; Sun, T.; et al. Serum oncostatin M is a potential biomarker of disease activity and infliximab response in inflammatory bowel disease measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay. Clin. Biochem. 2022, 100, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Fu, K.Z.; Pan, G. Role of Oncostatin M in the prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2024, 16, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, M.M.; Breen, E.C.; Magpantay, L.; Detels, R.; Lepone, L.; Penugonda, S.; Bream, J.H.; Jacobson, L.P.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Birmann, B.M. Temporal stability of serum concentrations of cytokines and soluble receptors measured across two years in low-risk HIV-seronegative men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Count | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 56 | 62.9 |

| Female | 33 | 37.1 |

| Proctitis (E1) | 6 | 6.7 |

| Left-sided colitis (E2) | 36 | 40.4 |

| Pancolitis (E3) | 47 | 52.8 |

| Clinical remission (pMS) | 29 | 32.6 |

| Active clinical disease (pMS) | 60 | 67.4 |

| Endoscopic remission | 32 | 36 |

| Active endoscopic disease | 57 | 64 |

| Histological remission | 7 | 7.9 |

| Active histological disease | 82 | 92.1 |

| Variable | Median (IQR) | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.0 (30.5–53.5) | 41.88 | 14.5 | 18 | 77 |

| OSM (pg/mL) | 49.12 (21.34–180.1) | 204.3 | 407 | 12.72 | 2338 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.44 (0.20–1.30) | 13.7 | 24.4 | 0.2 | 130 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 368.0 (306.5–433.0) | 370.96 | 79.46 | 215 | 568 |

| pMS | 6.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.79 | 2.35 | 2 | 11 |

| MES | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.86 | 0.78 | 0 | 3 |

| NHI | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.96 | 1.12 | 0 | 4 |

| FC (µg/g) | 202.0 (55.5–701.5) | 626.9 | 1124 | 7.19 | 7600 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jucan, A.-E.; Sarbu, G.-E.; Mihai, V.-C.; Atodiresei, C.; Juncu, S.; Mihai, I.-R.; Pavel-Tanasa, M.; Constantinescu, D.; Dranga, M.; Nedelciuc, O.; et al. Serum Oncostatin M in Ulcerative Colitis Patients and Its Relation to Disease Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010307

Jucan A-E, Sarbu G-E, Mihai V-C, Atodiresei C, Juncu S, Mihai I-R, Pavel-Tanasa M, Constantinescu D, Dranga M, Nedelciuc O, et al. Serum Oncostatin M in Ulcerative Colitis Patients and Its Relation to Disease Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010307

Chicago/Turabian StyleJucan, Alina-Ecaterina, Georgiana-Elena Sarbu, Vasile-Claudiu Mihai, Carmen Atodiresei, Simona Juncu, Ioana-Ruxandra Mihai, Mariana Pavel-Tanasa, Daniela Constantinescu, Mihaela Dranga, Otilia Nedelciuc, and et al. 2026. "Serum Oncostatin M in Ulcerative Colitis Patients and Its Relation to Disease Activity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010307

APA StyleJucan, A.-E., Sarbu, G.-E., Mihai, V.-C., Atodiresei, C., Juncu, S., Mihai, I.-R., Pavel-Tanasa, M., Constantinescu, D., Dranga, M., Nedelciuc, O., Iosep, D.-G., Danciu, M., Diaconescu, S., Gîlca-Blanariu, G.-E., Andronic, A. M., Toader, E., Drug, V.-L., Prelipcean, C. C., & Mihai, C. (2026). Serum Oncostatin M in Ulcerative Colitis Patients and Its Relation to Disease Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010307