Dopamine and the Gut Microbiota: Interactions Within the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Dopamine in the Gastrointestinal Tract

4. Microbial Production and Metabolism of Dopamine

5. Microbiota and Levodopa Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease

6. Pathways of Communication: From Gut Dopamine to Brain

7. Beyond Parkinson’s Disease: Emerging Links

8. Therapeutic Perspectives

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MGBA | microbiota–gut–brain axis |

| TyrDC | tyrosine decarboxylase |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorder |

| ADHD | attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| ENS | enteric nervous system |

| EC | enterochromaffin cells |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

References

- Xu, J.; Lu, Y. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and central nervous system diseases: From mechanisms of pathogenesis to therapeutic strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1583562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Margolis, K.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Mayer, E.A. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: From Motility to Mood. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1486–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costescu, M.; Paunescu, H.; Coman, O.A.; Coman, L.; Fulga, I. Antidepressant effect of the interaction of fluoxetine with granisetron. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 5108–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sittipo, P.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.K. The function of gut microbiota in immune-related neurological disorders: A review. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamah, S.; Aghazarian, A.; Nazaryan, A.; Hajnal, A.; Covasa, M. Role of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Regulating Dopaminergic Signaling. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.O.; Battagello, D.S.; Cardoso, A.R.; Hauser, D.N.; Bittencourt, J.C.; Correa, R.G. Dopamine: Functions, Signaling, and Association with Neurological Diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 39, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rekdal, V.M.; Bess, E.N.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Balskus, E.P. Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science 2019, 364, eaau6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini Rekdal, V.; Nol Bernadino, P.; Luescher, M.U.; Kiamehr, S.; Le, C.; Bisanz, J.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Bess, E.N.; Balskus, E.P. A widely distributed metalloenzyme class enables gut microbial metabolism of host- and diet-derived catechols. eLife 2020, 9, e50845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Kessel, S.P.; Frye, A.K.; El-Gendy, A.O.; Castejon, M.; Keshavarzian, A.; van Dijk, G.; El Aidy, S. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases restrict levels of levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Reynolds, R.; Tan, E.-K.; Pettersson, S. The role of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic options. Brain 2021, 144, 2571–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reunanen, S.; Ghemtio, L.; Patel, J.Z.; Patel, D.R.; Airavaara, K.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Jeltsch, M.; Xhaard, H.; Piepponen, P.T.; Tammela, P. Targeting bacterial and human levodopa decarboxylases for improved drug treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Discovery and characterization of new inhibitors. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 211, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wu, X. Brain Neurotransmitter Modulation by Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 649103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lyte, M. Microbial endocrinology in health and disease. BioEssays 2011, 33, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino Del Portillo, M.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Ruisoto, P.; Jimenez, M.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Beltran-Velasco, A.I.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Nutritional Modulation of the Gut-Brain Axis: A Comprehensive Review of Dietary Interventions in Depression and Anxiety Management. Metabolites 2024, 14, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Debs, L.H.; Patel, A.P.; Nguyen, D.; Patel, K.; O’Connor, G.; Grati, M.; Mittal, J.; Yan, D.; Eshraghi, A.A.; et al. Neurotransmitters: The critical modulators regulating gut–brain axis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 2359–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Sheng, S.; Zhang, F. Relationship Between Gut Bacteria and Levodopa Metabolism. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, X.; Lou, J.; Shan, W.; Ding, J.; Jin, Z.; Hu, Y.; Du, Q.; Liao, Q.; Xie, R.; Xu, J. Pathophysiologic Role of Neurotransmitters in Digestive Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 567650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, C.; Wang, G.Q.; Li, D.D.; Zhang, F. Microbiota-gut-brain axis in neurodegenerative diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayer, E.A.; Tillisch, K.; Gupta, A. Gut/brain axis and the microbiota. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Bergson, C.; Howard, R.L.; Lidow, M.S. Differential expression of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in the fetal primate cerebral wall. Cereb. Cortex 1997, 7, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Gao, G.; Yang, H. The Pathological Mechanism Between the Intestine and Brain in the Early Stage of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 861035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, Q.; Ma, S.R.; Zhao, Z.X.; Pan, L.B.; Cong, L.; Han, P.; Peng, R.; Yu, H.; Lin, Y.; et al. Oral berberine improves brain dopa/dopamine levels to ameliorate Parkinson’s disease by regulating gut microbiota. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Benea, S.-N.; Căruntu, C.; Nancoff, A.-S.; Homentcovschi, C.; Bucurica, S. Rewiring the Brain Through the Gut: Insights into Microbiota–Nervous System Interactions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruntu, C.; Boda, D.; Musat, S.; Caruntu, A.; Poenaru, E.; Calenic, B.; Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Draghia, A.; Rotaru, M.; Badarau, A. Stress effects on cutaneous nociceptive nerve fibers and their neurons of origin in rats. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. J. 2014, 19, 9517–9530. [Google Scholar]

- Poluektova, E.U.; Stavrovskaya, A.; Pavlova, A.; Yunes, R.; Marsova, M.; Koshenko, T.; Illarioshkin, S.; Danilenko, V. Gut Microbiome as a Source of Probiotic Drugs for Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiard, B.P.; Gotti, G. The High-Precision Liquid Chromatography with Electrochemical Detection (HPLC-ECD) for Monoamines Neurotransmitters and Their Metabolites: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.A.; King, K.Y.; Baldridge, M.T. Mouse Microbiota Models: Comparing Germ-Free Mice and Antibiotics Treatment as Tools for Modifying Gut Bacteria. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sandru, F.; Poenaru, E.; Stoleru, S.; Radu, A.M.; Roman, A.M.; Ionescu, C.; Zugravu, A.; Nader, J.M.; Baicoianu-Nitescu, L.C. Microbial Colonization and Antibiotic Resistance Profiles in Chronic Wounds: A Comparative Study of Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Venous Ulcers. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Heijtz, R.; Wang, S.; Anuar, F.; Qian, Y.; Björkholm, B.; Samuelsson, A.; Hibberd, M.L.; Forssberg, H.; Pettersson, S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3047–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socała, K.; Doboszewska, U.; Szopa, A.; Serefko, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Zielińska, A.; Poleszak, E.; Fichna, J.; Wlaź, P. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2021, 172, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menozzi, E.; Schapira, A.H.V. The Gut Microbiota in Parkinson Disease: Interactions with Drugs and Potential for Therapeutic Applications. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perez-Pardo, P.; Dodiya, H.B.; Engen, P.A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Huschens, A.M.; Shaikh, M.; Voigt, R.M.; Naqib, A.; Green, S.J.; Kordower, J.H.; et al. Role of TLR4 in the gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: A translational study from men to mice. Gut 2019, 68, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanz, J.E.; Spanogiannopoulos, P.; Pieper, L.M.; Bustion, A.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J. How to Determine the Role of the Microbiome in Drug Disposition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1588–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarkar, A.; Harty, S.; Lehto, S.M.; Moeller, A.H.; Dinan, T.G.; Dunbar, R.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Burnet, P.W. The microbiome in psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018, 22, 611–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ye, M.; Yan, F. A review of studies on gut microbiota and levodopa metabolism. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1046910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayer, E.A.; Knight, R.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Tillisch, K. Gut microbes and the brain: Paradigm shift in neuroscience. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15490–15496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaue, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Liu, S.; Ito, Y.; Yamanishi, Y.; Ando, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Mogi, M.; Nagai, M. Association of Enterococcus faecalis and tyrosine decarboxylase gene levels with levodopa pharmacokinetics in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut–brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A.H.; Lim, S.Y.; Chong, K.K.; AManap, M.A.A.; Hor, J.W.; Lim, J.L.; Low, S.C.; Chong, C.W.; Mahadeva, S.; Lang, A.E. Probiotics for Constipation in Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Neurology 2021, 96, e772–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shehawy, R.; Luecke-Johansson, S.; Ribbenstedt, A.; Gorokhova, E. Microbiota-Dependent and -Independent Production of l-Dopa in the Gut of Daphnia magna. mSystems 2021, 6, e0089221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DuPont, H.L.; Suescun, J.; Jiang, Z.D.; Brown, E.L.; Essigmann, H.T.; Alexander, A.S.; DuPont, A.W.; Iqbal, T.; Utay, N.S.; Newmark, M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson’s disease-A randomized repeat-dose, placebo-controlled clinical pilot study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, N.; Chen, S.-D.; Xiao, Q. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 70, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, D.; Hellström, P.M. Effects of Helicobacter pylori on Levodopa Pharmacokinetics. J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Misiti, F.; Marotta, G.; Falese, L.; Calabrò, G.E.; Mancone, S. The Gut Microbiome and Its Impact on Mood and Decision-Making: A Mechanistic and Therapeutic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; McVey Neufeld, K.-A. Gut–brain axis: How the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyte, M. Microbial endocrinology in the microbiome-gut-brain axis: How bacterial production and utilization of neurochemicals influence behavior. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Hardy, M.; Hillard, C.J.; Feix, J.B.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitigating gut microbial degradation of levodopa and enhancing brain dopamine: Implications in Parkinson’s disease. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varesi, A.; Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Fahmideh, F.; Pierella, E.; Romeo, M.; Ricevuti, G.; Nicoletta, M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Pascale, A. The Interplay between Gut Microbiota and Parkinson’s Disease: Implications on Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.K.; Thu, N.Q.; Tien, N.T.N.; Long, N.P.; Nguyen, H.T. Advancements in Mass Spectrometry-Based Targeted Metabolomics and Lipidomics: Implications for Clinical Research. Molecules 2024, 29, 5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanches, P.H.G.; de Melo, N.C.; Porcari, A.M.; de Carvalho, L.M. Integrating Molecular Perspectives: Strategies for Comprehensive Multi-Omics Integrative Data Analysis and Machine Learning Applications in Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Biology 2024, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.H.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.Y.; Yap, I.K.S.; Teh, C.S.J.; Loke, M.F.; Song, S.L.; Tan, J.Y.; Ang, B.H.; Tan, Y.Q.; et al. Gut Microbial Ecosystem in Parkinson Disease: New Clinicobiological Insights from Multi-Omics. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallen, Z.D.; Demirkan, A.; Twa, G.; Cohen, G.; Dean, M.N.; Standaert, D.G.; Sampson, T.R.; Payami, H. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghalandari, N.; Assarzadegan, F.; Habibi, S.A.H.; Esmaily, H.; Malekpour, H. Efficacy of Probiotics in Improving Motor Function and Alleviating Constipation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2023, 22, e137840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weis, S.; Schwiertz, A.; Unger, M.M.; Becker, A.; Faßbender, K.; Ratering, S.; Kohl, M.; Schnell, S.; Schäfer, K.H.; Egert, M. Effect of Parkinson’s disease and related medications on the composition of the fecal bacterial microbiota. npj Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nuzum, N.D.; Deady, C.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Mahony, S.M.; Clarke, G. More than just a number: The gut microbiota and brain function across the extremes of life. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2418988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Magistrelli, L.; Contaldi, E.; Visciglia, A.; Deusebio, G.; Pane, M.; Amoruso, A. The Impact of Probiotics on Clinical Symptoms and Peripheral Cytokines Levels in Parkinson’s Disease: Preliminary In Vivo Data. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waseem, M.H.; Abideen, Z.U.; Shoaib, A.; Rehman, N.; Osama, M.; Sajid, B.; Ahmad, R.; Fahim, Z.; Ansari, M.W.; Aimen, S.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2025, 17, 11795735251388781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Mustafa, M.; Usmani, N.; Habib, S. Microbiome-based therapies for Parkinson’s disease. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1496616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsiao, E.Y.; McBride, S.W.; Hsien, S.; Sharon, G.; Hyde, E.R.; McCue, T.; Codelli, J.A.; Chow, J.; Reisman, S.E.; Petrosino, J.F.; et al. Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell 2013, 155, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkki, H. Parkinson disease: Could gut microbiota influence severity of Parkinson disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felger, J.C.; Treadway, M.T. Inflammation effects on motivation and motor activity: Role of dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, N.; Hannoun, A.; Flahive, J.; Ward, D.; Goostrey, K.; Deb, A.; Smith, K.M. Effect of Levodopa Initiation on the Gut Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 574529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ai, P.; Xu, S.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, Z.; He, X.; Mo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, Q. Targeted Gut Microbiota Modulation Enhances Levodopa Bioavailability and Motor Recovery in MPTP Parkinson’s Disease Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirstea, M.S.; Creus-Cuadros, A.; Lo, C.; Yu, A.C.; Serapio-Palacios, A.; Neilson, S.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Finlay, B.B. A novel pathway of levodopa metabolism by commensal Bifidobacteria. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkovaca Latic, I.; Popovic, Z.; Mijatovic, K.; Sahinovic, I.; Pekic, V.; Vucic, D.; Cosic, V.; Miskic, B.; Tomic, S. Association of intestinal inflammation and permeability markers with clinical manifestations of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2024, 123, 106948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P.; et al. The gut microbiota influences blood–brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 263ra158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantozzi, M.; Pietroiusti, A.; Brusa, L.; Galati, S.; Stefani, A.; Lunardi, G.; Fedele, E.; Sancesario, G.; Bernardi, G.; Bergamaschi, A.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication and L-dopa absorption in patients with PD and motor fluctuations. Neurology 2006, 66, 1824–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddian-Green, R.G. Helicobacter pylori eradication and L-dopa absorption in patients with PD and motor fluctuations. Neurology 2007, 68, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sciscio, M.; Bryant, R.V.; Haylock-Jacobs, S.; Day, A.S.; Pitchers, W.; Iansek, R.; Costello, S.P.; Kimber, T.E. Faecal microbiota transplant in Parkinson’s disease: Pilot study to establish safety & tolerability. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2025, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, Y.; Helal, M.M.; Qutob, I.A.; Dawoud, A.I.A.; Allam, S.; Haddad, R.; Manasrah, G.M.; AlEdani, E.M.; Sleibi, W.; Faris, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation in the management of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Mo, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yan, Z.; Qian, Y.; Lai, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Association Between Microbial Tyrosine Decarboxylase Gene and Levodopa Responsiveness in Patients with Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2022, 99, e2443–e2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurelian, J.; Zamfirescu, A.; Nedelescu, M.; Stoleru, S.; Gidei, S.M.; Gita, C.D.; Prada, A.; Oancea, C.; Vladulescu-trandafir, A.I.; Aurelian, S.M. Vitamin D Impact on Stress and Cognitive Decline in Older Romanian Adults. FARMACIA 2024, 72, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, G.; Sampson, T.R.; Geschwind, D.H.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2016, 167, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lynch, L.E.; Lahowetz, R.; Maresso, C.; Terwilliger, A.; Pizzini, J.; Melendez Hebib, V.; Britton, R.A.; Maresso, A.W.; Preidis, G.A. Present and future of microbiome-targeting therapeutics. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e184323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-C.; Hung, C.-S.; Shen, M.-H.; Lai, C.-L.; Huang, C.-J. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites and Probiotic Strategies in Colorectal Cancer: Implications for Disease Modulation and Precision Therapy. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.G.; Stribinskis, V.; Rane, M.J.; Demuth, D.R.; Gozal, E.; Roberts, A.M.; Jagadapillai, R.; Liu, R.; Choe, K.; Shivakumar, B.; et al. Exposure to bacterial amyloids enhances α-synuclein aggregation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Scuderi, S.A.; Capra, A.P.; Giosa, D.; Bonomo, A.; Ardizzone, A.; Esposito, E. An Updated and Comprehensive Review Exploring the Gut–Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Neurotraumas: Implications for Therapeutic Strategies. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levite, M. Dopamine and T cells: Dopamine receptors and potent effects on T cells, dopamine production in T cells, and abnormalities in the dopaminergic system in T cells in autoimmune, neurological and psychiatric diseases. Acta Physiol. 2016, 216, 42–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, F.A.; Di Marzo, V. The gut microbiome, endocannabinoids and metabolic disorders. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 248, R83–R97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The microbiota–gut–brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.A.; Saltykova, I.V.; Zhukova, I.A.; Alifirova, V.M.; Zhukova, N.G.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.V.; Kovarsky, B.A.; Alekseev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 162, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzian, A.; Green, S.J.; Engen, P.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Mutlu, E.; Shannon, K.M. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero-Rodríguez, J.; Zimmermann, J.; Taubenheim, J.; Arias-Rodríguez, N.; Caicedo-Narvaez, J.D.; Best, L.; Mendieta, C.V.; López-Castiblanco, J.; Gómez-Muñoz, L.A.; Gonzalez-Santos, J.; et al. Changes in Bacterial Gut Composition in Parkinson’s Disease and Their Metabolic Contribution to Disease Development: A Gut Community Reconstruction Approach. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clapp, M.; Aurora, N.; Herrera, L.; Bhatia, M.; Wilen, E.; Wakefield, S. Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clin. Pract. 2017, 7, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Arancibia, C.; Urrutia-Piñones, J.; Illanes-González, J.; Martinez-Pinto, J.; Sotomayor-Zárate, R.; Julio-Pieper, M.; Bravo, J.A. Do your gut microbes affect your brain dopamine? Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCarlo, G.E.; Wallace, M.T. Modeling dopamine dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: From invertebrates to vertebrates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 133, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, M.; Yu, B.; Chen, D. The effects of gut microbiota on appetite regulation and the underlying mechanisms. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2414796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kurnik-Łucka, M.; Pasieka, P.; Łączak, P.; Wojnarski, M.; Jurczyk, M.; Gil, K. Gastrointestinal Dopamine in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, C.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qijie, L.; Khan, M.I.U.; Hassan, I.U.; Li, K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in neurological disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1225875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tan, A.H.; Hor, J.W.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.Y. Probiotics for Parkinson’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. JGH Open 2020, 5, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meiners, F.; Ortega-Matienzo, A.; Fuellen, G.; Barrantes, I. Gut microbiome-mediated health effects of fiber and polyphenol-rich dietary interventions. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1647740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Randeni, N.; Xu, B. Critical Review of the Cross-Links Between Dietary Components, the Gut Microbiome, and Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Elkamhawy, A.; Rakhalskaya, P.; Lu, Q.; Nada, H.; Quan, G.; Lee, K. Small Molecules in Parkinson’s Disease Therapy: From Dopamine Pathways to New Emerging Targets. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Pereira, M.; Silva, A.; Santos, J.; Saldanha, L.; Silva, I.; Magalhães, P.; Schmidt, S.; Vale, N. Advancing Precision Medicine: A Review of Innovative In Silico Approaches for Drug Development, Clinical Pharmacology and Personalized Healthcare. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Kessel, S.P.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F.; El Aidy, S. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylase associates with clinical variables in a longitudinal cohort study of Parkinsons disease. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abouelela, M.E.; Helmy, Y.A. Next-Generation Probiotics as Novel Therapeutics for Improving Human Health: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, O.P.-C.; Ben Okon, M.; Alum, E.U.; Ugwu, C.N.M.; Anyanwu, E.G.; Mariam, B.; Ogenyi, F.C.B.; Eze, V.H.U.; Anyanwu, C.N.; Ezeonwumelu, J.O.C.; et al. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of the gut microbiota–brain axis: Novel insights and clinical applications in neurological disorders. Medicine 2025, 104, e43542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Intestinal Dopamine | Mechanism | Principal Local Functions | Evidence (Representative References) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterochromaffin (EC) cells | Tyrosine → L-DOPA → dopamine via aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC); paracrine release to ENS | Modulation of motility, secretion, epithelial barrier tone | MGBA overviews; Front. Microbiol. 2025 [1]; Metabolites 2024 [17] |

| Enteric nervous system (ENS) and sympathetic fibers | Neuronal synthesis and synaptic release onto smooth muscle and secretory epithelium | Fine-tuning of peristalsis (D1/D2-family effects), fluid and electrolyte transport | Reviews on gut dopaminergic signaling; J. Cell. Physiol. 2017 [18] |

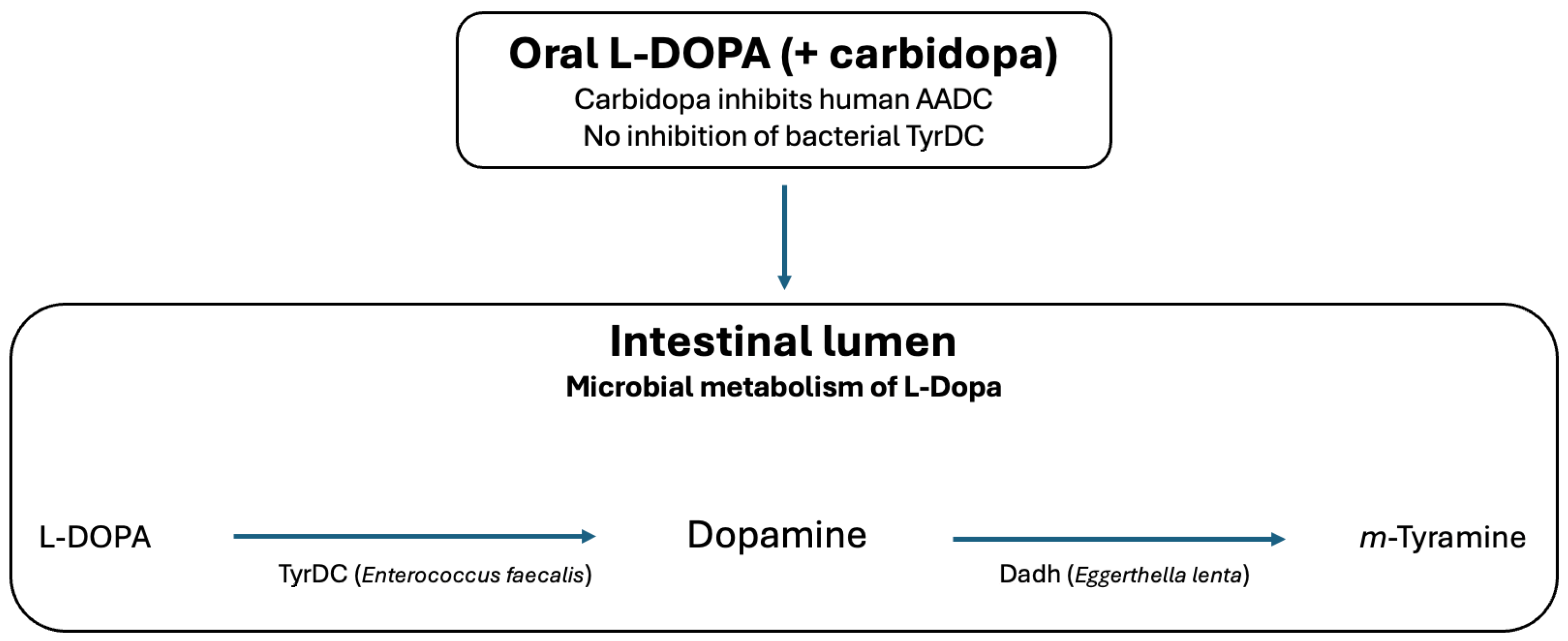

| Microbiota-derived pathways | (i) Enterococcus faecalis TyrDC: L-DOPA → dopamine; (ii) Eggerthella lenta Dadh: dopamine → m-tyramine | Potential alteration of luminal catecholamine exposure; reduces L-DOPA availability | Science 2019 [8]; eLife 2020 [9]; Nat. Commun. 2019 [10] |

| Additional microbial taxa | Reported dopamine synthesis by Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Clostridium spp. | Potential neuromodulation; hypothesized barrier and immune effects | Biomedicines 2022 [6] |

| Immune compartment cross-talk | Dopamine receptors on T cells and macrophages; cytokine modulation | Regulation of mucosal immunity and inflammation | Brain 2021 [11]; Cell 2016 [19] |

| Microbial Species | Enzyme | Substrate → Product | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecalis | Tyrosine decarboxylase (TyrDC), PLP-dependent | L-DOPA → dopamine | Rekdal et al., Science 2019 [8] |

| Eggerthella lenta | Catechol dehydroxylase (Dadh), molybdenum-dependent | Dopamine → m-tyramine | Bisanz et al., Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018 [38] |

| Clostridium spp. | Multiple decarboxylases and reductases | Tyrosine/catecholamines → various metabolites | Strandwitz, Brain Res. 2018 [4] |

| Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus spp. | Putative tyrosine decarboxylases | Tyrosine → dopamine | Lyte, BioEssays 2011 [15] |

| Helicobacter pylori | Indirect effects on absorption and metabolism | Reduced bioavailability of therapeutic L-DOPA | Front. Neurol. 2023 [41] |

| Study/Period | Intervention/Population | Main Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010s, observational cohorts | H. pylori eradication in PD patients | Improved L-DOPA absorption and motor symptoms | Brain 2021 [11] |

| Rekdal et al. 2019; Bisanz et al. 2018 | Mechanistic characterization of TyrDC (E. faecalis) and Dadh (E. lenta) | Defined two-step microbial L-DOPA degradation pathway | Science 2019 [8]; Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018 [38] |

| 2022–2024 pilot studies | Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in PD | Safe; preliminary benefit for motor and non-motor symptoms | Front. Neurol. 2023; ClinicalTrials.gov [48] |

| 2024–2025 experimental therapies | Selective bacterial TyrDC/Dadh inhibitors + carbidopa | Enhanced systemic and central L-DOPA availability (preclinical/early translational) | Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025 [12] |

| Pathway | Mechanism | Representative Evidence | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural (ENS and vagus nerve) | Dopamine modulates enteric neurons and vagal afferents; vagotomy abolishes microbial effects | Germ-free and vagotomy animal models | Links gut dopamine to central motor and reward circuits |

| Immune | Dopamine receptors on T cells and macrophages regulate IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ | PD and IBD models | Peripheral immune modulation influences neuroinflammation |

| Metabolic/Endocrine | Interaction with SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites, GLP-1, and ghrelin | Metabolomics and multi-omics MGBA studies | Regulation of appetite, energy balance, reward |

| Barrier function (gut and BBB) | Dopamine modulates tight junction proteins and permeability | Experimental models | Facilitates cytokine/metabolite entry into CNS |

| Condition | Proposed Mechanism | Key Evidence | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression and anxiety | Microbial modulation of dopaminergic mood and reward circuits | Germ-free models; human dysbiosis studies | Potential adjunctive probiotic or FMT strategies |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders (ASD, ADHD) | Microbiota-driven alterations in striatal dopamine signaling | Animal models | Microbiome-targeted adjunct therapies |

| Metabolic disorders and feeding behavior | Interaction with SCFAs, ghrelin, leptin affecting reward-based eating | Animal studies | Targeting dopaminergic pathways for weight management |

| Gastrointestinal and immune disorders (IBD) | Dopamine-dependent regulation of mucosal immunity and barrier integrity | Human mucosal studies | Probiotic/prebiotic strategies to reduce inflammation |

| Strategy | Mechanism | Stage of Evidence | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics/Prebiotics | Modulate microbial composition; enhance beneficial taxa (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) | Pilot RCTs; animal models | Brain 2021 [11]; Neurology 2021 [46] |

| Dietary interventions | High-fiber diet → SCFA production; polyphenols inhibit microbial decarboxylases | Observational and experimental studies | Metabolites 2024 [17] |

| Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) | Restores microbial balance; indirectly normalizes dopamine metabolism | Pilot clinical trials in PD | Front. Neurol. 2023 [48] |

| Pharmacological inhibition | Small-molecule inhibitors of bacterial TyrDC and Dadh | Preclinical and translational studies | Science 2019 [8]; eLife 2020 [9] |

| Precision medicine approaches | Biomarker-guided stratification (TyrDC/Dadh genes, m-tyramine, metabolomics) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbu, A.C.; Stoleru, S.; Zugravu, A.; Poenaru, E.; Dragomir, A.; Costescu, M.; Aurelian, S.M.; Shhab, Y.; Stoleru, C.M.; Coman, O.A.; et al. Dopamine and the Gut Microbiota: Interactions Within the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010271

Barbu AC, Stoleru S, Zugravu A, Poenaru E, Dragomir A, Costescu M, Aurelian SM, Shhab Y, Stoleru CM, Coman OA, et al. Dopamine and the Gut Microbiota: Interactions Within the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010271

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbu, Aurelia Cristiana, Smaranda Stoleru, Aurelian Zugravu, Elena Poenaru, Adrian Dragomir, Mihnea Costescu, Sorina Maria Aurelian, Yara Shhab, Clara Maria Stoleru, Oana Andreia Coman, and et al. 2026. "Dopamine and the Gut Microbiota: Interactions Within the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Perspectives" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010271

APA StyleBarbu, A. C., Stoleru, S., Zugravu, A., Poenaru, E., Dragomir, A., Costescu, M., Aurelian, S. M., Shhab, Y., Stoleru, C. M., Coman, O. A., & Fulga, I. (2026). Dopamine and the Gut Microbiota: Interactions Within the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010271