Insights into the Complex Biological Network Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

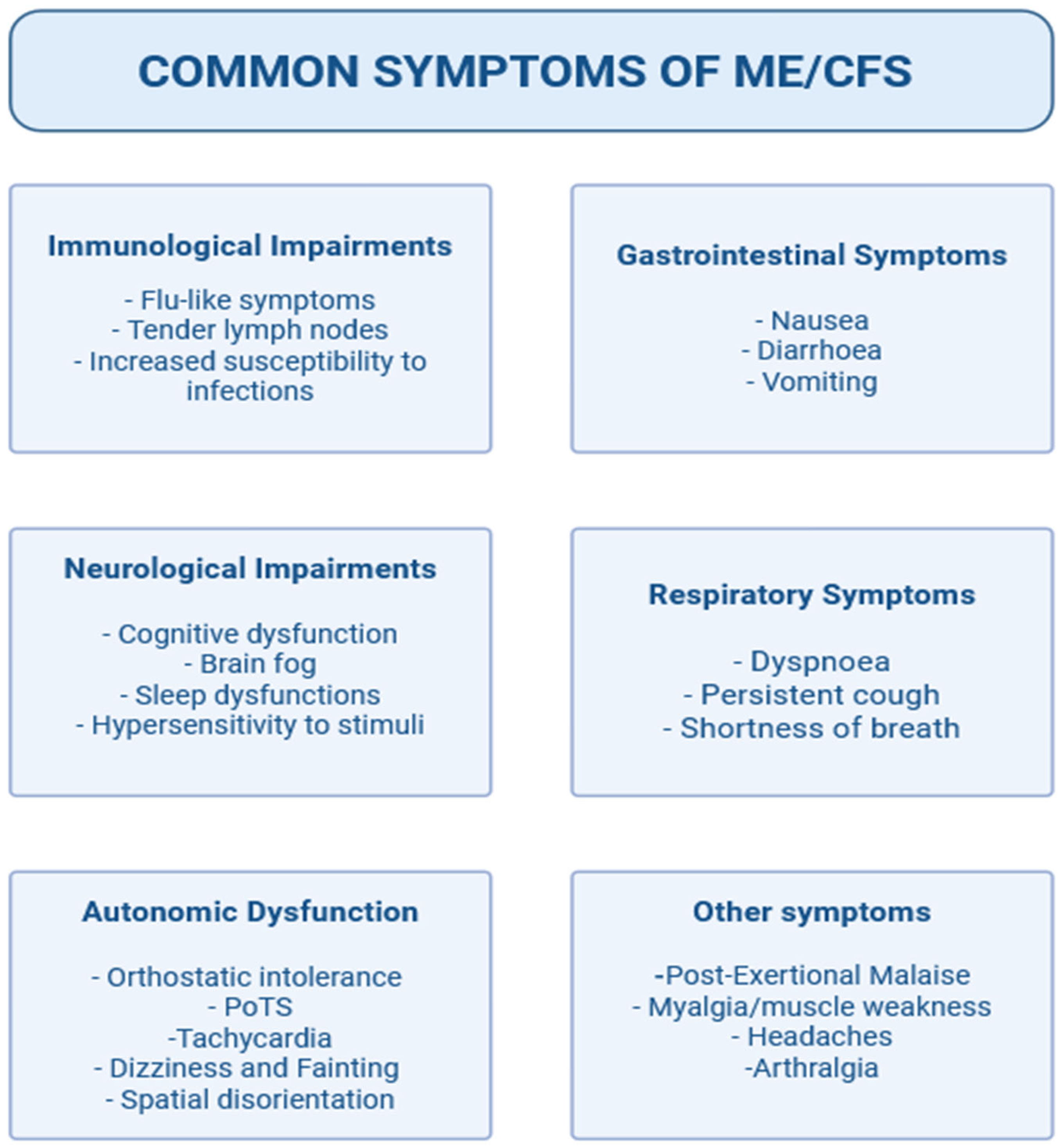

2. Definition

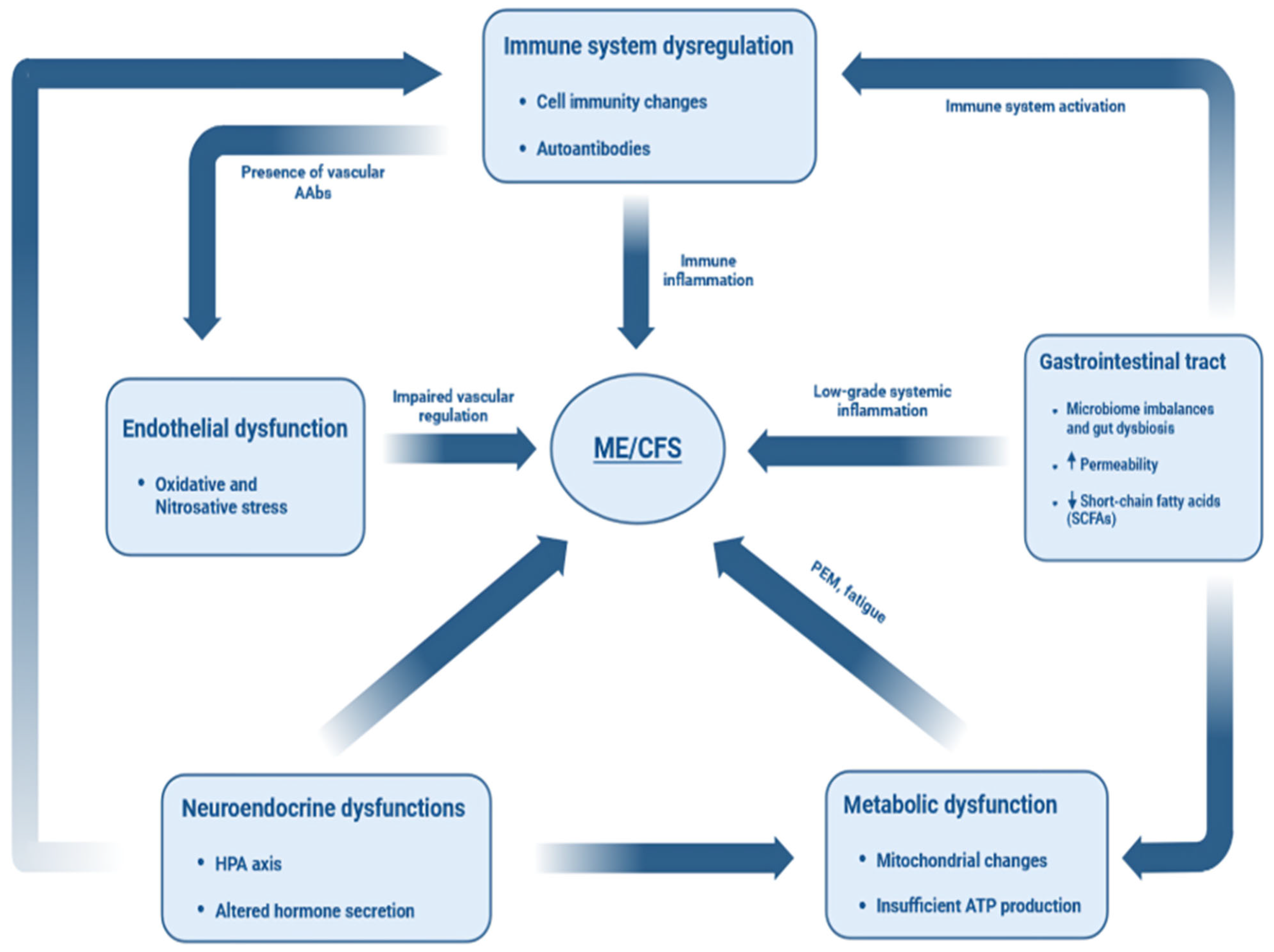

3. Etiology

4. Immunopathology

5. Gastrointestinal Tract Dysbiosis

6. Neuroendocrine Interactions

7. Metabolic Impairments

8. Endothelial Dysfunction

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAbs | Autoantibodies |

| Abs | Antibodies |

| AdR | Adrenergic Receptor |

| AECAs | Anti-Endothelial Cell Antibodies |

| ANA | Antinuclear Antibodies |

| APC | Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| Ca2+ | Calcium Ion |

| CAMs | Cell Adhesion Molecules |

| CBG | Cortisol-Binding Globulin |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| dsDNA | Double-Stranded DNA |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr Virus |

| FAO | Fatty Acid Oxidation |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GH | Growth Hormone |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| HCs | Healthy Controls |

| HHV | Human Herpes Virus |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis |

| ICC | International Consensus Criteria |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| IGF | Insulin-Like Growth Factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| IST | Insulin Stress Test |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| mAChR | Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

| Nabs | Natural Antibodies |

| NK | Natural Killer (Cells) |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NO2 | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PEM | Post-Exertional Malaise |

| POTS | Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SNPs | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| SNVs | Single-Nucleotide Variants |

| T3 | Triiodothyronine |

| T4 | Thyroxine |

| TCR | T-Cell Receptor |

| TORC1 | Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cell |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

References

- Lim, E.J.; Ahn, Y.C.; Jang, E.S.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Son, C.G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). J. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotzny, F.; Blanco, J.; Capelli, E.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Steiner, S.; Murovska, M.; Scheibenbogen, C. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome—Evidence for an autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board on the Health of Select Populations. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness; Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.P.; Kaplan, J.E.; Gantz, N.M.; Komaroff, A.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Straus, S.E.; Jones, J.F.; Dubois, R.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Pahwa, S.; et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: A working case definition. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988, 108, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, M.C.; Archard, L.C.; Banatvala, J.E.; Borysiewicz, L.K.; Clare, A.W.; David, A.; Edwards, R.H.; Hawton, K.E.; Lambert, H.P.; Lane, R.J.; et al. A report--chronic fatigue syndrome: Guidelines for research. J. R. Soc. Med. 1991, 84, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.C.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A. The Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Comprehensive Approach to Its Definition and Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, E.; Goudsmit, E.G.; Macintyre, A.; Shepherd, C.B. “London Criteria for M.E.” Report from The National Task Force on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome (PVFS), Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). 1994. Available online: https://meassociation.org.uk/2011/02/london-criteria-for-m-e/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lemer, A.M.; Bested, A.C.; Flor-Henry, P.; Joshi, P.; Peter Powles, A.C.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J. Chronic. Fatigue Syndr. 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A.C.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM 2015 Diagnostic Criteria|Diagnosis|Healthcare Providers|Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)|CDC n.d. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/hcp/diagnosis/iom-2015-diagnostic-criteria-1.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management NICE Guideline 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Rasa, S.; Nora-Krukle, Z.; Henning, N.; Eliassen, E.; Shikova, E.; Harrer, T.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Murovska, M.; Prusty, B.K. Chronic viral infections in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, H.M.; Lee, E.J.; Lim, E.J.; Son, C.G. REVIEW Open Access Evaluation of viral infection as an etiology of ME/CFS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolini, A.M.; Miller, S.D. The role of infections in autoimmune disease 2008. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 155, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, J.; Gottfries, C.G.; Elfaitouri, A.; Rizwan, M.; Rosén, A. Infection elicited autoimmunity and Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An explanatory model. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 308084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, R.S.; Albrich, W.C.; Kahlert, C.R.; Bahr, L.S.; Löber, U.; Vernazza, P.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Forslund, S.K. The Gut Microbiome in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 628741, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 878196.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The impact of gut microbiota on brain and behaviour: Implications for psychiatry. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheedy, J.R.; Wettenhall, R.E.H.; Scanlon, D.; Gooley, P.R.; Lewis, D.P.; Mcgregor, N.; Stapleton, D.I.; Butt, H.L.; DE Meirleir, K.L. Increased D-Lactic Acid Intestinal Bacteria in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. In Vivo 2009, 23, 621. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Che, X.; Briese, T.; Ranjan, A.; Allicock, O.; Yates, R.A.; Cheng, A.; March, D.; Hornig, M.; Komaroff, A.L.; et al. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Hargreaves, I.P.; Domingo, J.C.; Castro-Marrero, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Post-Viral Fatigue Syndrome: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, C.; Brown, A.; Strassheim, V.; Elson, J.; Newton, J.; Manning, P. Cellular bioenergetics is impaired in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186802, Correction in PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192817.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Fitch, N.; Du Preez, S.; Cabanas, H.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. A systematic review of natural killer cells profile and cytotoxic function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, T.K.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. ERK1/2, MEK1/2 and p38 downstream signalling molecules impaired in CD56dimCD16+ and CD56brightCD16dim/- natural killer cells in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, N.; Cabanas, H.; Balinas, C.; Klein, A.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Rituximab impedes natural killer cell function in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis patients: A pilot in vitro investigation. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Hoag, G.E.; Salerno, J.P.; Hornig, M.; Klimas, N.; Selin, L.K. Identification of CD8 T-cell dysfunction associated with symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long COVID and treatment with a nebulized antioxidant/anti-pathogen agent in a retrospective case series. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 36, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, J. Surveying the Metabolic and Dysfunctional Profiles of T Cells and NK Cells in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarano, A.H.; Maya, J.; Giloteaux, L.; Peterson, D.L.; Maynard, M.; Gottschalk, C.G.; Hanson, M.R. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients exhibit altered T cell metabolism and cytokine associations. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, J.; Indre Bileviciute-Ljungar Tesi, B.; Schlums, H.; Johnsgaard, M.S.; Asadi-Azarbaijani, B.; Bolle Strand, E.; Bryceson, Y.T. Unperturbed cytotoxic lymphocyte phenotype and function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 248175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.L.; Palencia, T.; Fernández, G.; García, M. Association of T and NK cell phenotype with the diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 341493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenu, E.W.; van Driel, M.L.; Staines, D.R.; Ashton, K.J.; Hardcastle, S.L.; Keane, J.; Tajouri, L.; Peterson, D.; Ramos, S.B.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Longitudinal investigation of natural killer cells and cytokines in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Brenu, E.; Broadley, S.; Kwiatek, R.; Ng, J.; Nguyen, T.; Freeman, S.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Regulatory T, natural killer T and γδ T cells in multiple sclerosis and chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A comparison. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 34, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.S.; Ford, B.; Bansal, A.S. Altered functional B cell subset populations in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared to healthy controls. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 172, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenu, E.W.; Huth, T.K.; Hardcastle, S.L.; Fuller, K.; Kaur, M.; Johnston, S.; Ramos, S.B.; Staines, D.R.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Role of adaptive and innate immune cells in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Int. Immunol. 2014, 26, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, L.; Mikhaylova, S.V.; Capelli, E.; Ferrari, D.; Ngonga, G.K.; Ricevuti, G. Immunological aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 2009, 8, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natelson, B.H.; Haghighi, M.H.; Ponzio, N.M. Evidence for the Presence of Immune Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2002, 9, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, G.; Fuite, J.; Kreitz, A.; Vernon, S.D.; Klimas, N.; Fletcher, M.A. A formal analysis of cytokine networks in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010, 24, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenu, E.W.; van Driel, M.L.; Staines, D.R.; Ashton, K.J.; Ramos, S.B.; Keane, J.; Klimas, N.G.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Immunological abnormalities as potential biomarkers in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, S.; Ray, K.K.; Buckland, M.; White, P.D. Chronic fatigue syndrome and circulating cytokines: A systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 50, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornig, M.; Montoya, J.G.; Klimas, N.G.; Levine, S.; Felsenstein, D.; Bateman, L.; Peterson, D.L.; Gottschalk, C.G.; Schultz, A.F.; Che, X.; et al. Distinct plasma immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, K.; Von Mikecz, A.; Buchwald, D.; Jones, J.; Gerace, L.; Tan, E.M. Autoantibodies to nuclear envelope antigens in chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikai, M.; Tomomatsu, S.; Hankins, R.W.; Takagi, S.; Miyachi, K.; Kosaka, S.; Akiya, K. Autoantibodies to a 68/48 kDa protein in chronic fatigue syndrome and primary fibromyalgia: A possible marker for hypersomnia and cognitive disorders. Rheumatology 2001, 40, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebel, M.; Grabowski, P.; Heidecke, H.; Bauer, S.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Wittke, K.; Meisel, C.; Reinke, P.; Volk, H.D.; Fluge, Ø.; et al. Antibodies to β adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 52, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Kuratsune, H.; Hidaka, Y.; Hakariya, Y.; Tatsumi, K.I.; Takano, T.; Kanakura, Y.; Amino, N. Autoantibodies against muscarinic cholinergic receptor in chronic fatigue syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 12, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mikecz, A.; Konstantinov, K.; Buchwald, D.S.; Gerace, L.; Tan, E.M. High frequency of autoantibodies to insoluble cellular antigens in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokama, Y.; Empey-Campora, C.; Hara, C.; Higa, N.; Siu, N.; Lau, R.; Kuribayashi, T.; Yabusaki, K. Acute phase phospholipids related to the cardiolipin of mitochondria in the sera of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), chronic ciguatera fish poisoning (CCFP), and other diseases attributed to chemicals, Gulf War, and marine toxins. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2008, 22, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokama, Y.; Campora, C.E.; Hara, C.; Kuribayashi, T.; Le Huynh, D.; Yabusaki, K. Anticardiolipin antibodies in the sera of patients with diagnosed chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2009, 23, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Hernandez, O.D.; Cuccia, M.; Bozzini, S.; Bassi, N.; Moscavitch, S.; Diaz-Gallo, L.M.; Blank, M.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Shoenfeld, Y. Autoantibodies, Polymorphisms in the Serotonin Pathway, and Human Leukocyte Antigen Class II Alleles in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1173, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Ouchi, Y.; Nakatsuka, D.; Tahara, T.; Mizuno, K.; Tajima, S.; Onoe, H.; Yoshikawa, E.; Tsukada, H.; Iwase, M.; et al. Reduction of [11C](+)3-MPB Binding in Brain of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome with Serum Autoantibody against Muscarinic Cholinergic Receptor. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaskamp, L.; Roubal, C.; Uddin, S.; Sotzny, F.; Kedor, C.; Bauer, S.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Seifert, M. Serum of Post-COVID-19 Syndrome Patients with or without ME/CFS Differentially Affects Endothelial Cell Function In Vitro. Cells 2022, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Berg, P.A. High incidence of antibodies to 5-hydroxytryptamine, gangliosides and phospholipids in patients with chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia syndrome and their relatives: Evidence for a clinical entity of both disorders. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1995, 1, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sasso, E.M.; Muraki, K.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Smith, P.; Jeremijenko, A.; Griffin, P.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Investigation into the restoration of TRPM3 ion channel activity in post-COVID-19 condition: A potential pharmacotherapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1264702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliff, J.M.; King, E.C.; Lee, J.S.; Sepúlveda, N.; Wolf, A.S.; Kingdon, C.; Bowman, E.; Dockrell, H.M.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.; et al. Cellular immune function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 422277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, N.G.; Salvato, F.R.; Morgan, R.; Fletcher, M.A. Immunologic abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landay, A.L.; Lennette, E.T.; Jessop, C.; Levy, J.A. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical condition associated with immune activation. Lancet 1991, 338, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, L.; Rohrhofer, J.; Zehetmayer, S.; Stingl, M.; Untersmayr, E. Article evaluation of immune dysregulation in an austrian patient cohort suffering from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda, N.; Carneiro, J.; Lacerda, E.; Nacul, L. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome as a Hyper-Regulated Immune System Driven by an Interplay Between Regulatory T Cells and Chronic Human Herpesvirus Infections. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 479474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgarth, N. B-1 cell heterogeneity and the regulation of natural and antigen-induced IgM production. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 215204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluge, Ø.; Bruland, O.; Risa, K.; Storstein, A.; Kristoffersen, E.K.; Sapkota, D.; Næss, H.; Dahl, O.; Nyland, H.; Mella, O. Benefit from B-Lymphocyte Depletion Using the Anti-CD20 Antibody Rituximab in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. A Double-Blind and Placebo-Controlled Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekeland, I.G.; Sørland, K.; Neteland, L.L.; Fosså, A.; Alme, K.; Risa, K.; Dahl, O.; Tronstad, K.J.; Mella, O.; Fluge, Ø. Six-year follow-up of participants in two clinical trials of rituximab or cyclophosphamide in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluge, Ø.; Rekeland, I.G.; Lien, K.; Thürmer, H.; Borchgrevink, P.C.; Schäfer, C.; Sørland, K.; Aßmus, J.; Ktoridou-Valen, I.; Herder, I.; et al. B-Lymphocyte Depletion in Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygiel-Górniak, B.; Mazurkiewicz, Ł. Positive antiphospholipid antibodies: Observation or treatment? J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2023, 56, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Mihaylova, I.; Leunis, J.-C.; Maes, M. Chronic fatigue syndrome is accompanied by an IgM-related immune response directed against neopitopes formed by oxidative or nitrosative damage to lipids and proteins. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2006, 27, 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, M.; Mihaylova, I.; Kubera, M.; Leunis, J.C.; Twisk, F.N.M.; Geffard, M. IgM-mediated autoimmune responses directed against anchorage epitopes are greater in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) than in major depression. Metab. Brain Dis. 2012, 27, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, A.; Fluge, Ø.; Strand, E.B.; Flåm, S.T.; Sosa, D.D.; Mella, O.; Egeland, T.; Saugstad, O.D.; Lie, B.A.; Viken, M.K. Human Leukocyte Antigen alleles associated with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibble, J.J.; McGrath, S.J.; Ponting, C.P. Genetic risk factors of ME/CFS: A critical review. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, R117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Taylor, K.; Kozubek, J.; Sardell, J.; Gardner, S. Genetic risk factors for ME/CFS identified using combinatorial analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, P.; Carrillo-Trabalón, F.; Sánchez-Labraca, N.; Cañadas, F.; Estévez, A.F.; Cardona, D. Are probiotic treatments useful on fibromyalgia syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome patients? A systematic review. Benef. Microbes 2018, 9, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bested, A.C.; Marshall, L.M. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev. Environ. Health 2015, 30, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Preez, S.; Corbitt, M.; Cabanas, H.; Eaton, N.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. A systematic review of enteric dysbiosis in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; Neidhöfer, S.; Matthias, T. The gut microbiome feelings of the brain: A perspective for non-microbiologists. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Mahony, S.M. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: From bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frémont, M.; Coomans, D.; Massart, S.; De Meirleir, K. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals alterations of intestinal microbiota in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Anaerobe 2013, 22, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.; Round, J.L. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.; Gunter, C.; Fleming, E.; Vernon, S.D.; Bateman, L.; Unutmaz, D.; Oh, J. Multi-‘omics of gut microbiome-host interactions in short- and long-term myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 273–287.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, G.F.D.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Lorusso, L.; Manara, E.; Bertelli, M.; Puglisi, E.; Capelli, E. Potential role of microbiome in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelits (CFS/ME). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitami, T.; Fukuda, S.; Kato, T.; Yamaguti, K.; Nakatomi, Y.; Yamano, E.; Kataoka, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kogo, Y.; et al. Deep phenotyping of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in Japanese population. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Cao, Y.; Ma, H.; Guo, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Causal Effects between Gut Microbiome and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1190894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarano, A.H.; Giloteaux, L.; Keller, B.A.; Levine, S.M.; Hanson, M.R. Eukaryotes in the gut microbiota in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.W.; McGregor, N.R.; Lewis, D.P.; Butt, H.L.; Gooley, P.R. The association of fecal microbiota and fecal, blood serum and urine metabolites in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.K.; Cook, D.; Meyer, J.; Vernon, S.D.; Le, T.; Clevidence, D.; Robertson, C.E.; Schrodi, S.J.; Yale, S.; Frank, D.N. Changes in Gut and Plasma Microbiome following Exercise Challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy-Szakal, D.; Williams, B.L.; Mishra, N.; Che, X.; Lee, B.; Bateman, L.; Klimas, N.G.; Komaroff, A.L.; Levine, S.; Montoya, J.G.; et al. Fecal metagenomic profiles in subgroups of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome 2017, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giloteaux, L.; Hanson, M.R.; Keller, B.A. A Pair of Identical Twins Discordant for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Differ in Physiological Parameters and Gut Microbiome Composition. Am. J. Case Rep. 2016, 17, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giloteaux, L.; Goodrich, J.K.; Walters, W.A.; Levine, S.M.; Ley, R.E.; Hanson, M.R. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome 2016, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navaneetharaja, N.; Griffiths, V.; Wileman, T.; Carding, S.R. A role for the intestinal microbiota and virome in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)? J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arron, H.E.; Marsh, B.D.; Kell, D.B.; Khan, M.A.; Jaeger, B.R.; Pretorius, E. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The biology of a neglected disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1386607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Maya, R.W.; Abass, M.A.; Gupta, J.; Singh, A.; Joshi, K.K.; Premkumar, J.; Sahoo, S.; Khosravi, M. The potential therapeutic approaches targeting gut health in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A narrative review. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmach, A.; Quickert, S.; Puta, C.; Reuken, P.A. The gastrointestinal microbiota in the development of ME/CFS: A critical view and potential perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1352744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deumer, U.S.; Varesi, A.; Floris, V.; Savioli, G.; Mantovani, E.; López-Carrasco, P.; Rosati, G.M.; Prasad, S.; Ricevuti, G. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): An Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varesi, A.; Deumer, U.S.; Ananth, S.; Ricevuti, G. The Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Current Evidence and Potential Therapeutic Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Mihaylova, I.; Leunis, J.C. Increased serum IgA and IgM against LPS of enterobacteria in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): Indication for the involvement of gram-negative enterobacteria in the etiology of CFS and for the presence of an increased gut-intestinal permeability. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 99, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sehrawy, A.A.M.A.; Ayoub, I.I.; Uthirapathy, S.; Ballal, S.; Gabble, B.C.; Singh, A.; Panigrahi, R.; Kamali, M.; Khosravi, M. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative review of an emerging field. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2025, 35, 13690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjö, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petra, A.I.; Panagiotidou, S.; Hatziagelaki, E.; Stewart, J.M.; Conti, P.; Theoharides, T.C. Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis and Its Effect on Neuropsychiatric Disorders with Suspected Immune Dysregulation. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Anderson, G.; Maes, M. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6806–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, A.V.; Rivier, C.L. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis by Cytokines: Actions and Mechanisms of Action. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.J.; Saadé, N.E.; Safieh-Garabedian, B. Cytokines and neuro-immune-endocrine interactions: A role for the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal revolving axis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2002, 133, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanculescu, D.; Larsson, L.; Bergquist, J. Theory: Treatments for Prolonged ICU Patients May Provide New Therapeutic Avenues for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Front. Med. 2021, 8, 672370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Núñez, B.; Tarasse, R.; Vogelaar, E.F.; Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.J.; Muskiet, F.A.J. Higher Prevalence of “Low T3 Syndrome” in Patients With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 328134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.B.; William, A.H.; Strauss, A.C.; Unger, E.R.; Jason, L.A.; Marshall, G.D.; Dimitrakoff, J.D. Chronic fatigue syndrome: The current status and future potentials of emerging biomarkers. Fatigue 2014, 2, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Twisk, F.N.M.; Kubera, M.; Ringel, K.; Leunis, J.C.; Geffard, M. Increased IgA responses to the LPS of commensal bacteria is associated with inflammation and activation of cell-mediated immunity in chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Affect Disord. 2012, 136, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, A.J. The neuroendocrinology of chronic fatigue syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, L.M.; Cleare, A.J.; Ormel, J.; Manoharan, A.; Kok, I.C.; Wessely, S.; Rosmalen, J.G. Meta-analysis and meta-regression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in functional somatic disorders. Biol. Psychol. 2011, 87, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Harding, S.; Sorenson, M.; Jason, L.; Reynolds, N.; Brown, M.; Maher, K.; Fletcher, M.A.; Reynolds, N.; Brown, M. The Associations Between Basal Salivary Cortisol and Illness Symptomatology in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2008, 13, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhof, S.L.; Rutten, J.M.T.M.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; Bleijenberg, G.; Kimpen, J.L.L.; van de Putte, E.M. The role of hypocortisolism in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 42, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.V.; Burnett, F.; Medbak, S.; Dinan, T.G. Naloxone-mediated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.C.; Mastronardi, C.; Silva-Aldana, C.T.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Lidbury, B.A. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofford, L.J.; Young, E.A.; Engleberg, N.C.; Korszun, A.; Brucksch, C.B.; McClure, L.A.; Brown, M.B.; Demitrack, M.A. Basal circadian and pulsatile ACTH and cortisol secretion in patients with fibromyalgia and/or chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.S.; Cleare, A.J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyller, V.B.; Vitelli, V.; Sulheim, D.; Fagermoen, E.; Winger, A.; Godang, K.; Bollerslev, J. Altered neuroendocrine control and association to clinical symptoms in adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome: A cross-sectional study. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 121, Erratum in J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 157.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, D.A.; Amsterdam, J.D.; Levine, S.; McCann, S.M.; Moore, R.C.; Newbrand, C.H.; Allen, G.; Nisenbaum, R.; Pfaff, D.W.; Tsokos, G.C.; et al. Neuroendocrine Aspects of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Neuroimmunomodulation 2004, 11, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, K. Down-regulation of renin–aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone systems in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, C.; Newton, J.; Watson, S. A Review of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. ISRN Neurosci. 2013, 2013, 784520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanriverdi, F.; Karaca, Z.; Unluhizarci, K.; Kelestimur, F. The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome. Stress 2007, 10, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, S.; Brkic, S.; Lendak, D.; Maric, D.; Medic Stojanoska, M.; Novakov Mikic, A. Neuroendocrine disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 47, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, A.J.; Sookdeo, S.S.; Jones, J.; O’Keane, V.; Miell, J.P. Integrity of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor system is maintained in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorkens, G.; Berwaerts, J.; Wynants, H.; Abs, R. Characterization of pituitary function with emphasis on GH secretion in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2000, 53, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavyani, B.; Lidbury, B.A.; Schloeffel, R.; Fisher, P.R.; Missailidis, D.; Annesley, S.J.; Dehhaghi, M.; Heng, B.; Guillemin, G.J. Could the kynurenine pathway be the key missing piece of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) complex puzzle? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missailidis, D.; Annesley, S.J.; Allan, C.Y.; Sanislav, O.; Lidbury, B.A.; Lewis, D.P.; Fisher, P.R. An Isolated Complex V Inefficiency and Dysregulated Mitochondrial Function in Immortalized Lymphocytes from ME/CFS Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missailidis, D.; Sanislav, O.; Allan, C.Y.; Smith, P.K.; Annesley, S.J.; Fisher, P.R. Dysregulated Provision of Oxidisable Substrates to the Mitochondria in ME/CFS Lymphoblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, A.; Barupal, D.K.; Levine, S.M.; Hanson, M.R. Comprehensive Circulatory Metabolomics in ME/CFS Reveals Disrupted Metabolism of Acyl Lipids and Steroids. Metabolites 2020, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Miyazawa, T.; Burdeos, G.C.; Miyazawa, T. Biological Functions of Antioxidant Dipeptides. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2022, 68, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 19, 175, Correction in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 673.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naviaux, R.K.; Naviaux, J.C.; Li, K.; Bright, A.T.; Alaynick, W.A.; Wang, L.; Baxter, A.; Nathan, N.; Anderson, W.; Gordon, E. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5472–E5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeus, M.; Nijs, J.; Hermans, L.; Goubert, D.; Calders, P. The role of mitochondrial dysfunctions due to oxidative and nitrosative stress in the chronic pain or chronic fatigue syndromes and fibromyalgia patients: Peripheral and central mechanisms as therapeutic targets? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2013, 17, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Maes, M. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metab. Brain Dis. 2014, 29, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Maes, M. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Immune-Inflammatory Pathways in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2014, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M. Inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways underpinning chronic fatigue, somatization and psychosomatic symptoms. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. The potential role of ischaemia–reperfusion injury in chronic, relapsing diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Long COVID, and ME/CFS: Evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 1653–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinat, R.; Villalobos-Labra, R.; Hofmann, L.; Blauensteiner, J.; Sepúlveda, N.; Westermeier, F. Decreased NO production in endothelial cells exposed to plasma from ME/CFS patients. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2022, 143, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.K.; Janakidevi, K.; Lai, L.; Malik, A.B. Hydrogen peroxide-induced increase in endothelial adhesiveness is dependent on ICAM-1 activation. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1993, 264, L406–L412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluge, Ø.; Tronstad, K.J.; Mella, O. Pathomechanisms and possible interventions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e150377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakov, N.; Szklarski, M.; Hartwig, J.; Sotzny, F.; Lorenz, S.; Meyer, A.; Grabowski, P.; Doehner, W.; Scheibenbogen, C. Peripheral endothelial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.; Scheibenbogen, C. A Unifying Hypothesis of the Pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ß2-adrenergic receptors. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, M.K.; Sørland, K.; Leirgul, E.; Rekeland, I.G.; Stavland, C.S.; Mella, O.; Fluge, Ø. Endothelial dysfunction in ME/CFS patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.M.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. Cardiovascular and haematological pathology in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A role for viruses. Blood Rev. 2023, 60, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year/Name of Criteria | Core Requirements | Duration of Symptoms | Additional Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988—CDC (Holmes) | Debilitating fatigue + exclusion of other causes | ≥6 months | Diagnosis requires ≥ 8 of 11 symptoms (fever, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, insomnia, etc.) or 6 symptoms + ≥2 physical findings (fever, pharyngitis, tender nodes) | [4] |

| 1991—Oxford | Fatigue as main symptom, definite onset, debilitating, present ≥ 50% of time | ≥6 months | Includes psychiatric conditions; recognizes post-infectious subtype | [5] |

| 1994—CDC (Fukuda) | Chronic fatigue (unexplained, disabling, not lifelong, not relieved by rest) + ≥4 of memory/concentration problems, sore throat, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, arthralgia, new headaches, unrefreshing sleep, PEM > 24 h | ≥6 months | Widely used in research; requires exclusion of psychiatric and medical causes | [6] |

| 1994—London Criteria | Fatigue triggered by exertion, impaired short-term memory/concentration, fluctuating symptoms | ≥6 months | Autonomic/immune symptoms common; initially research-oriented | [7] |

| 2003—Canadian Consensus | Severe fatigue, PEM/fatigue, sleep dysfunction, myalgia, ≥2 neuro/cognitive symptoms, + ≥1 symptom from ≥2 of autonomic, neuroendocrine, immune | ≥6 months | Excludes primary psychiatric illness; 2010 revision added functional impairment thresholds | [8] |

| 2011—International Consensus (ICC) | Post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion (PENE) + ≥1 neurological, ≥3 immune/GI/GU, ≥1 energy production symptom | No duration requirement | Focused on biological abnormalities; defines severity levels (mild → very severe) | [9] |

| 2015—Institute of Medicine (IOM) | Fatigue, PEM, unrefreshing sleep + (cognitive impairment or orthostatic intolerance) | ≥6 months; symptoms ≥ 50% of time with moderate severity | Simplified for clinical use; CDC currently adopts this | [10] |

| 2021—UK NICE Guideline | Fatigue, PEM, unrefreshing/disturbed sleep, cognitive difficulties | ≥6 weeks (adults), ≥4 weeks (children) | Practical clinical guideline; emphasizes early recognition | [11] |

| Virus | Evidence/Association | Proposed Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) | Frequently reported in onset cases; serological evidence of reactivation | Latent infection in B cells, molecular mimicry, autoimmunity trigger | [12,13,14] |

| Human Herpes viruses (HHV-6A, HHV-6B, HHV-7, HHV-8) | Detected in tissues/sera of ME/CFS patients | Latency/reactivation, immune dysregulation | [12,13] |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Reported in subsets of patients | Chronic infection, immune exhaustion | [12,13] |

| Human Parvovirus B19 | Linked to ME/CFS onset in case studies | Autoimmunity trigger via tissue damage and antigen release | [12,13] |

| Enteroviruses | Historical outbreaks associated with CFS-like illness | Persistent infection, chronic inflammation | [12] |

| Retroviruses (XMRV, others) | Early studies suggested association, later disputed | Chronic immune activation | [12] |

| Ross River virus | Post-viral fatigue syndrome documented after outbreaks | Post-viral immune dysregulation | [12] |

| Coronaviruses (incl. SARS-CoV-2) | Post-COVID-19 syndrome overlaps with ME/CFS phenotype | Persistent immune activation, autoimmunity | [12,13] |

| Immune Component | Reported Alteration | Clinical/Functional Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK cells | ↓ Cytotoxic activity; altered phenotype (↓ perforin, granzyme; impaired MAPK and Ca2+ signaling) | Reduced viral clearance, chronic infection risk | [23,24,25] |

| CD8+ T cells | Exhaustion phenotype (↑ PD-1, CTLA-4, TIGIT; ↓ proliferation, ↓ mitochondrial potential) | Impaired viral control, chronic inflammation | [26,27,28] |

| CD4+ T cells | ↓ Glycolysis, ↑ fatty acid oxidation | Metabolic dysfunction, immune exhaustion | [27,28] |

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | Conflicting: ↑ count in some studies, ↓ in others | Dysregulated tolerance, possible autoimmunity | [29,30,31,32] |

| B cells | ↑ Naïve and transitional B cells; ↑ CD20+CD5+ subset | Impaired antibody regulation, autoantibody production | [33,34,35,36] |

| Cytokines | Contradictory reports: Th2 skewing in some studies, mixed Th1/Th2 in others | Heterogeneous immune activation states | [37,38,39,40] |

| Autoantibodies–ANA | Varying prevalence in different studies (13–68%) | Non-specific marker of autoimmunity | [41,42,43,44,45] |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibodies | Varying prevalence in different studies (4–90%) | Thrombosis, vascular abnormalities | [46,47,48] |

| Anti-β2 adrenergic receptor (AdR) Abs | Detected in patients | Orthostatic intolerance, POTS, BP dysregulation | [43] |

| Anti-muscarinic AChR (M1, M3, M4) Abs | Detected in multiple cohorts | Muscle weakness, cholinergic dysfunction | [44,49] |

| Anti-endothelial cell Abs (AECA) | Detected in patients | Vascular dysregulation, hypoxia, cognitive dysfunction | [50] |

| Other autoantibodies (dsDNA, gangliosides, phospholipids) | Varying prevalence in different studies | Possible neurological and vascular symptoms | [46,47,48,51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dudova, D.; Bozhkova, M.; Petrov, S.; Nikolova, R.; Kalfova, T.; Ivanovska, M.; Vaseva, K.; Nikolova, M.; Ivanov, I.N. Insights into the Complex Biological Network Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010268

Dudova D, Bozhkova M, Petrov S, Nikolova R, Kalfova T, Ivanovska M, Vaseva K, Nikolova M, Ivanov IN. Insights into the Complex Biological Network Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudova, Dobrina, Martina Bozhkova, Steliyan Petrov, Ralitsa Nikolova, Teodora Kalfova, Mariya Ivanovska, Katya Vaseva, Maria Nikolova, and Ivan N. Ivanov. 2026. "Insights into the Complex Biological Network Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010268

APA StyleDudova, D., Bozhkova, M., Petrov, S., Nikolova, R., Kalfova, T., Ivanovska, M., Vaseva, K., Nikolova, M., & Ivanov, I. N. (2026). Insights into the Complex Biological Network Underlying Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010268