Harnessing Moringa oleifera for Immune Modulation in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods/Literature Search Strategy

3. Chemical Composition of Moringa oleifera

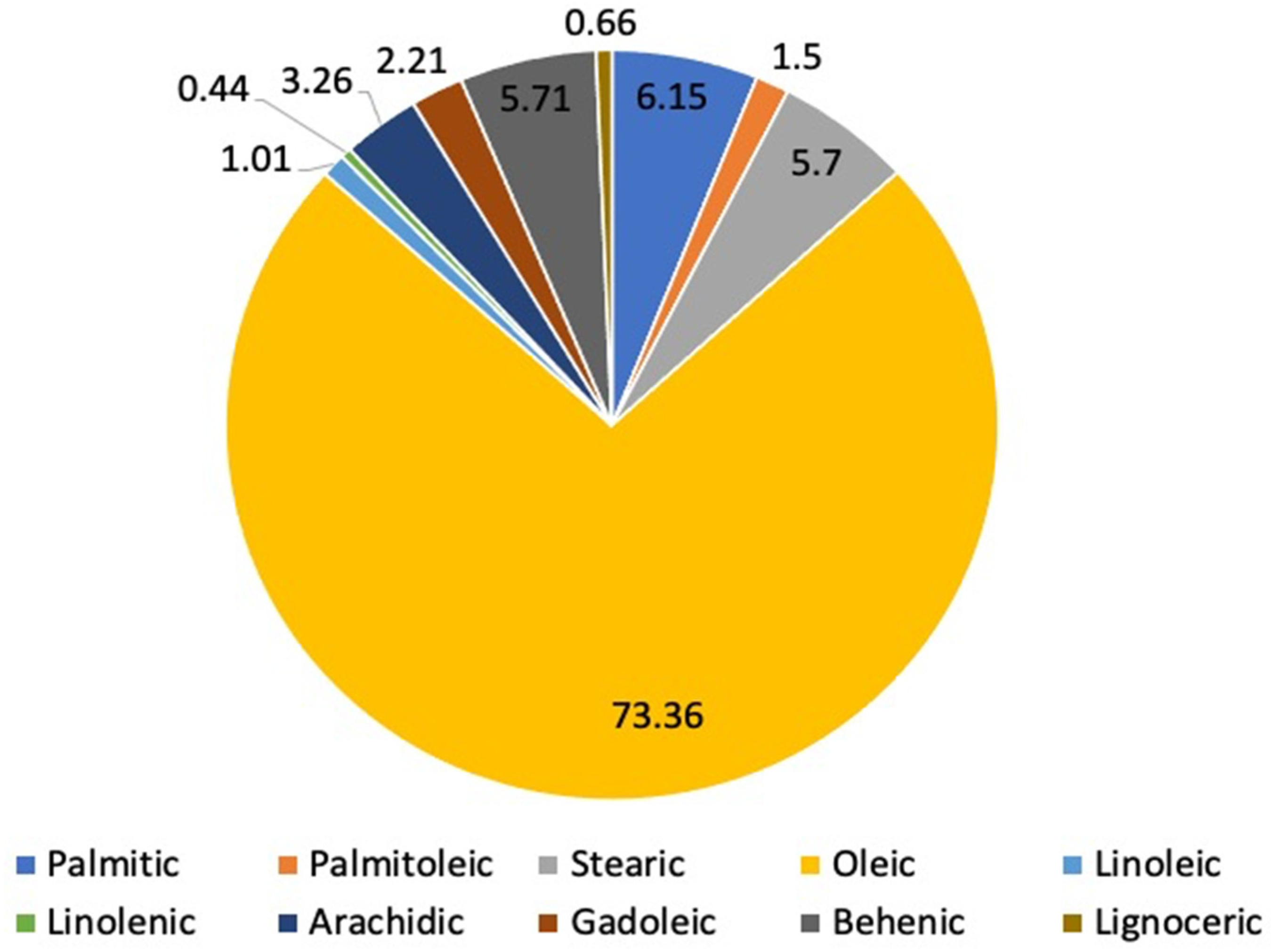

3.1. Seeds

3.2. Leaves

3.3. Roots

3.4. Stems

4. The Impact of Moringa oleifera on the Immune System

4.1. Moringa oleifera Effect on Innate and Adaptive Immunity

4.2. Cellular Responses and Cytokine Pathways in Innate and Adaptive Immunity

4.3. Multilevel Modulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity

4.3.1. Gut Microbiota Modulation

4.3.2. Immune Modulation and Anti-Inflammatory Balance

4.4. Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Moringa oleifera

5. Moringa oleifera and Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential

5.1. Apoptosis, Proliferation, and Cell-Cycle Control in Moringa oleifera-Mediated Cancer Progression

5.2. Moringa oleifera in Cancer: Dual Regulation of Oncogenic Signaling and Oxidative Stress

5.3. Inhibition of Angiogenesis and Metastasis Progression

5.4. From Bench to Bedside: Addressing Translation Challenges in Moringa oleifera-Based Cancer Therapy

6. Clinical Trials on the Immunomodulatory Properties of Moringa oleifera in Disease Prevention and Cancer Therapy

7. Long-Term Safety and Toxicity of Moringa oleifera

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCR7 | C-C Chemokine Receptor Type 7 |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| HSP70 | Heat Shock Protein 70 |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| MOP | Moringa oleifera Polysaccharide |

| Mop3 | Motif 3 Protein |

| MRP-1 | Moringa Root Polysaccharide 1 |

| NLRP3 | NOD (Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization) LRR (Leucine-Rich Repeat) Pyrin Domain-containing Protein 3 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H: Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 |

| PGE-2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PTP1B | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

References

- Pant, T.; Uche, N.; Juric, M.; Zielonka, J.; Bai, X. Regulation of Immunomodulatory Networks by Nrf2-Activation in Immune Cells: Redox Control and Therapeutic Potential in Inflammatory Diseases. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelec, M.; Detka, J.; Mieszczak, P.; Sobocińska, M.K.; Majka, M. Immunomodulation—A General Review of the Current State-of-the-Art and New Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1127704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kroemer, G. The Cancer-Immune Dialogue in the Context of Stress. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnet Le Provost, K.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G.; Bezu, L. Trial Watch: Dexmedetomidine in Cancer Therapy. OncoImmunology 2024, 13, 2327143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, J.; Iwaszkiewicz-Grześ, D.; Cholewiński, G. Approaches Towards Better Immunosuppressive Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 1230–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La-Beck, N.M.; Owoso, J. Updates and Emerging Trends in the Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 11, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, S.; Debnath, T. Drugs Used for Immunomodulation. In Essentials of Pharmacodynamics and Drug Action; Chakraverty, R., Mathur, R., Chakraborty, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 229–240. ISBN 978-981-97-2776-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, R.; Mathew, M.; Patel, K.K.; Reddy, S.A.; Haider, Z.; Naria, M.; Habib, A.; Abdin, Z.U.; Razzaq Chaudhry, W.; Akbar, A. Effects of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and Gastroprotective NSAIDs on the Gastrointestinal Tract: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Suzuki, C.; Honda, Y.; Fernandez, J.L. Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness of Vonoprazan for Prevention of Gastric and Duodenal Ulcer Recurrence in Patients on Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Japan: A 12-Month Post-Marketing Surveillance Study. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2023, 22, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakik, R.M.; Alqahtani, N.I.; Al-Hagawi, Y.; Nasser Alsharif, S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Hadi Asiri, D.; Al-Mani, S.Y. Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Diaphragms and Strictures Induced by Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Through Intraoperative Enteroscopy: A Case Study from Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e59752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.; Park, J.M.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, B.-W.; Choi, M.-G.; Kim, N.J. Drugs Effective for Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs or Aspirin-Induced Small Bowel Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 58, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, L.A.M.; Andreassen, B.K.; Stenehjem, J.S.; Heir, T.; Karlstad, Ø.; Juzeniene, A.; Ghiasvand, R.; Larsen, I.K.; Green, A.C.; Veierød, M.B.; et al. Use of Immunomodulating Drugs and Risk of Cutaneous Melanoma: A Nationwide Nested Case-Control Study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Haider, M.F. A Comprehensive Review on Glucocorticoids Induced Osteoporosis: A Medication Caused Disease. Steroids 2024, 207, 109440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubosaka, M.; Maruyama, M.; Lui, E.; Kushioka, J.; Toya, M.; Gao, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Zhang, N.; et al. Preclinical Models for Studying Corticosteroid-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2024, 112, e35360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Hsu, C.L.; Langley, A.; Wojcik, C.; Iraganje, E.; Grygiel-Górniak, B. Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis—From Molecular Mechanism to Clinical Practice. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2024, 40, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgert, K.D. Immunology: Understanding the Immune System, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-08157-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kamran, M.; Hussain, S.; Abid, M.A.; Syed, S.K.; Suleman, M.; Riaz, M.; Iqbal, M.; Mahmood, S.; Saba, I.; Qadir, R. Phytochemical Composition of Moringa oleifera Its Nutritional and Pharmacological Importance. Postep. Biol. Komorki 2020, 47, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Rana, H.K.; Tshabalala, T.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, A.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Pandey, A.K. Phytochemical, Nutraceutical and Pharmacological Attributes of a Functional Crop Moringa oleifera Lam: An Overview. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, E.; Blundell, R. A Comprehensive Review of the Phytochemicals, Health Benefits, Pharmacological Safety and Medicinal Prospects of Moringa oleifera. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, A.; Pant, M.; Gupta, M.M.; Kashania, P.; Ratan, Y.; Jain, V.; Pareek, A.; Chuturgoon, A.A. Moringa oleifera: An Updated Comprehensive Review of Its Pharmacological Activities, Ethnomedicinal, Phytopharmaceutical Formulation, Clinical, Phytochemical, and Toxicological Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owon, M.; Osman, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Salama, M.A.; Matthäus, B. Characterisation of Different Parts from Moringa oleifera Regarding Protein, Lipid Composition and Extractable Phenolic Compounds. OCL 2021, 28, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Spada, A.; Battezzati, A.; Schiraldi, A.; Aristil, J.; Bertoli, S. Moringa oleifera Seeds and Oil: Characteristics and Uses for Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, M.; Essandoh, P.K.; Asare, R.K.; Nazir, K.-H. The Value Chain of Moringa oleifera Plant and the Process of Producing Its Biodiesel in Ghana. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 1827514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Ashraf, M.; Bhanger, M.I. Interprovenance Variation in the Composition of Moringa oleifera Oilseeds from Pakistan. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2005, 82, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, P. It’s Time for an Oil Change! Opportunities for High-Oleic Vegetable Oils. Inf.-Int. News Fats Oils Relat. Mater. 2003, 14, 480–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gharsallah, K.; Rezig, L.; Msaada, K.; Chalh, A.; Soltani, T. Chemical Composition and Profile Characterization of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 137, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Invally, M.; Sanzagiri, R.; Buttar, H.S. Evaluation of the Antidepressant Activity of Moringa oleifera Alone and in Combination with Fluoxetine. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2015, 6, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masitlha, E.P.; Seifu, E.; Teketay, D. Nutritional Composition and Mineral Profile of Leaves of Moringa oleifera Provenances Grown in Gaborone, Botswana. Food Prod. Process Nutr. 2024, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrufo, T.; Nazzaro, F.; Mancini, E.; Fratianni, F.; Coppola, R.; De Martino, L.; Agostinho, A.B.; De Feo, V. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of the Essential Oil from Leaves of Moringa oleifera Lam. Cultivated in Mozambique. Molecules 2013, 18, 10989–11000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, S.; Pandey, V.K.; Dixit, R.; Rustagi, S.; Suthar, T.; Atuahene, D.; Nagy, V.; Ungai, D.; Ahmed, A.E.M.; Kovács, B.; et al. Exploring the Phytochemical, Pharmacological and Nutritional Properties of Moringa oleifera: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.B.; Das, A.K.; Banerji, N. Chemical Investigations on the Gum Exudate from Sajna (Moringa oleifera). Carbohydr. Res. 1982, 102, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, S.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Saleem, R.; Siddiqui, S.; Aftab, K.; Gilani, A.H. Isolation and Structure Elucidation of New Nitrile and Mustard Oil Glycosides from Moringa oleifera and Their Effect on Blood Pressure. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, C.; Rojas-Silva, P.; Tumer, T.B.; Kuhn, P.; Richard, A.J.; Wicks, S.; Stephens, J.M.; Wang, Z.; Mynatt, R.; Cefalu, W.; et al. Isothiocyanate-rich Moringa oleifera Extract Reduces Weight Gain, Insulin Resistance, and Hepatic Gluconeogenesis in Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Qian, Y.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Peng, L.-J.; Mao, J.-Y.; Yang, M.-R.; Tian, Y.; Sheng, J. Isothiocyanate from Moringa oleifera Seeds Inhibits the Growth and Migration of Renal Cancer Cells by Regulating the PTP1B-Dependent Src/Ras/Raf/ERK Signaling Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 790618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Núñez, M.L.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Berhow, M.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Glucosinolate-Rich Hydrolyzed Extract from Moringa oleifera Leaves Decreased the Production of TNF-α and IL-1β Cytokines and Induced ROS and Apoptosis in Human Colon Cancer Cells. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodur, G.M.; Olson, M.E.; Wade, K.L.; Stephenson, K.K.; Nouman, W.; Garima; Fahey, J.W. Wild and Domesticated Moringa oleifera Differ in Taste, Glucosinolate Composition, and Antioxidant Potential, but Not Myrosinase Activity or Protein Content. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarina; Wani, A.W.; Rawat, M.; Kaur, H.; Das, S.; Kaur, T.; Akram, N.; Faisal, Z.; Jan, S.S.; Oyshe, N.N.; et al. Medicinal Utilization and Nutritional Properties of Drumstick (Moringa oleifera)—A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 4546–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engsuwan, J.; Waranuch, N.; Limpeanchob, N.; Ingkaninan, K. HPLC Methods for Quality Control of Moringa oleifera Extract Using Isothiocyanates and Astragalin as Bioactive Markers. ScienceAsia 2017, 43, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Rasul, A.; Hussain, G.; Zahoor, M.K.; Jabeen, F.; Subhani, Z.; Younis, T.; Ali, M.; Sarfraz, I.; Selamoglu, Z. Astragalin: A Bioactive Phytochemical with Potential Therapeutic Activities. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 2018, 9794625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Fiorillo, G.; Criscuoli, F.; Ravasenghi, S.; Santagostini, L.; Fico, G.; Spadafranca, A.; Battezzati, A.; Schiraldi, A.; Pozzi, F. Nutritional Characterization and Phenolic Profiling of Moringa oleifera Leaves Grown in Chad, Sahrawi Refugee Camps, and Haiti. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18923–18937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zduńska, K.; Dana, A.; Kolodziejczak, A.; Rotsztejn, H. Antioxidant Properties of Ferulic Acid and Its Possible Application. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Rutka, A.; Blicharska, E.; Tatarczak-Michalewska, M.; Kulik-Siarek, K.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Malinowska, M.A.; Szopa, A. Moringa oleifera (Drumstick Tree)—Nutraceutical, Cosmetological and Medicinal Importance: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1288382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkon, F.; Hasan, S.; Salam, K.A.; Mosaddik, M.A.; Khondkar, P.; Haque, M.E.; Rahman, M. Benzylcarbamothioethionate from Root Bark of Moringa oleifera Lam. and Its Toxicological Evaluation. Boletín Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2009, 8, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Alhakmani, F.; Kumar, S.; Khan, S.A. Estimation of Total Phenolic Content, in–Vitro Antioxidant and Anti–Inflammatory Activity of Flowers of Moringa oleifera. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atawodi, S.E.; Atawodi, J.C.; Idakwo, G.A.; Pfundstein, B.; Haubner, R.; Wurtele, G.; Bartsch, H.; Owen, R.W. Evaluation of the Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Properties of Methanol Extracts of the Leaves, Stem, and Root Barks of Moringa oleifera Lam. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calva, J.; Cuenca, M.B.; León, A.; Benítez, Á. Chemical Composition, Acetylcholinesterase-Inhibitory Potential and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Three Populations of Parthenium Hysterophorus L. in Ecuador. Molecules 2025, 30, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaspina, P.; Polito, F.; Mainetti, A.; Khedhri, S.; De Feo, V.; Cornara, L. Exploring Chemical Variability in the Essential Oil of Artemisia Absinthium L. in Relation to Different Phenological Stages and Geographical Location. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 20, e00743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hridoy, A.A.M.; Munny, F.J.; Shahriar, F.; Rahman, M.; Islam, F.; Kazmi, A.; Kawsar, A.; Bailey, C. Exploring the Potentials of Sajana (Moringa oleifera Lam.) as a Plant-Based Feed Ingredient to Sustainable and Good Aquaculture Practices: An Analysis of Growth Performance and Health Benefits. Aquac. Res. 2025, 2025, 3580123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilaoui, M.; Mouse, H.A.; Jaafari, A.; Zyad, A. Comparative Phytochemical Analysis of Essential Oils from Different Biological Parts of Artemisia Herba Alba and Their Cytotoxic Effect on Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M.; Sapuan, S.; Hashim, I.F.; Ismail, N.I.; Yaakop, A.S.; Kamaruzaman, N.A.; Mokhtar, A.M.A. The Properties and Mechanism of Action of Plant Immunomodulators in Regulation of Immune Response—A Narrative Review Focusing on Curcuma longa L., Panax Ginseng C. A. Meyer and Moringa oleifera Lam. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, F. Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Moringa oleifera in Neurodegeneration: Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Neuroprotective Mechanisms. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 3653–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, H.G.; Younis, N.A.; Saleh, S.Y. Comparative Physiological and Immunological Impacts of Moringa oleifera Leaf and Seed Water Supplements on African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus): Effects on Disease Resistance and Health Parameters. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, M.T.; Gallardo, W.; Salin, K.R.; Pumpuang, S.; Chavan, B.R.; Bhujel, R.C.; Medhe, S.V.; Kettawan, A.; Thompson, K.D.; Pirarat, N. Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on the Growth Performance, Hematology, Innate Immunity, and Disease Resistance of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) against Streptococcus Agalactiae Biotype 2. Animals 2024, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Al Junaidi, H.S.; Alshaeri, H.K.; Alasmari, M.M.; Hadi, R.W.; Alsayed, A.R.; Law, D. Immunomodulatory and Anticancer Effects of Moringa Polyherbal Infusions: Potentials for Preventive and Therapeutic Use. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1597602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Q.; Hua, H.; Zhao, J. Advancements in Plant-Derived sRNAs Therapeutics: Classification, Delivery Strategies, and Therapeutic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai Ud Din, R.; Eman, S.; Zafar, M.H.; Chong, Z.; Saleh, A.A.; Husien, H.M.; Wang, M. Moringa oleifera as a Multifunctional Feed Additive: Synergistic Nutritional and Immunomodulatory Mechanisms in Livestock Production. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1615349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazim, A.M.; Afifi, M.; Abu-Alghayth, M.H.; Alkadri, D.H. Moringa oleifera: Recent Insights for Its Biochemical and Medicinal Applications. J. Food Biochem. 2024, 2024, 1270903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, Q.; Chang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Z. Moringa oleifera Leaf Polysaccharides Exert Anti-Lung Cancer Effects upon Targeting TLR4 to Reverse the Tumor-Associated Macrophage Phenotype and Promote T-Cell Infiltration. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 4607–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentina, A.S.; Nugroho, T.; Susilaningsih, N. The Effect of Ethanolic Extract of Moringa oleifera Leaves on the Macrophage Count and VEGF Expression on Wistar Rats with Burn Wound. Biosci. Med. J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 2022, 6, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Song, S. The Potential Role of Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf Proteins in Moringa Allergy by Functionally Activating Murine Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells and Inducing Their Differentiation toward a Th2-Polarizing Phenotype. Nutrients 2023, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilotos, J.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Mowa, C.N.; Opata, M.M. Moringa oleifera Treatment Increases Tbet Expression in CD4+ T Cells and Remediates Immune Defects of Malnutrition in Plasmodium Chabaudi-Infected Mice. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, U.K.; Mediani, A.; Rohani, E.R.; Tong, X.; Han, R.; Misnan, N.M.; Jam, F.A.; Bunawan, H.; Sarian, M.N.; Hamezah, H.S. A Comprehensive Review with Updated Future Perspectives on the Ethnomedicinal and Pharmacological Aspects of Moringa oleifera. Molecules 2022, 27, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.M.; Lee, S.; Huh, J.-E.; Perumalsamy, H.; Balusamy, S.R.; Kim, Y.-J. Fermentation of Moringa oleifera Lam. Using Bifidobacterium Animalis Subsp. Lactis Enhances the Anti-Inflammatory Effect in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 109, 105752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, M.; Sakran, T.; Badawi, Y.K.; Abdel-Hady, D.S. Influence of Moringa oleifera Extract, Vitamin C, and Sodium Bicarbonate on Heat Stress-Induced HSP70 Expression and Cellular Immune Response in Rabbits. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestà, M.; Minutolo, A.; Gismondi, A.; Canuti, L.; Kenzo, M.; Roglia, V.; Macchi, F.; Grelli, S.; Canini, A.; Colizzi, V.; et al. Cytotoxic and Apoptotic Effects of Different Extracts of Moringa oleifera Lam on Lymphoid and Monocytoid Cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhy, T.I.; Adam, D.; Azis, Z.M.R.; Syahputri, V.; Yuliani, M.G.A.; Suwarto, M.F.S.; Setiawan, F. The Potential of Moringa Leaf Nanoparticles (Moringa oleifera) on the Expression of TNFα, IL10, and HSP 27 in Oral Cavity Cancer. J. Multidiscip. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2024, 4, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-J.; Debnath, T.; Tang, Y.; Ryu, Y.-B.; Moon, S.-H.; Kim, E.-K. Topical Application of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract Ameliorates Experimentally Induced Atopic Dermatitis by the Regulation of Th1/Th2/Th17 Balance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omodanisi, E.I.; Aboua, Y.G.; Chegou, N.N.; Oguntibeju, O.O. Hepatoprotective, Antihyperlipidemic, and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Moringa oleifera in Diabetic-Induced Damage in Male Wistar Rats. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 182. [Google Scholar]

- Drue, G.; Minor, R.C. Moringa oleifera Tea Alters Neutrophil but Not Lymphocyte Levels in Blood of Acutely Stressed Mice. Madridge J. Immunol. 2018, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husni, E.; Badriyya, E.; Putri, L.; Aldi, Y. The Effect of Ethanol Extract of Moringa Leaf (Moringa oleifera Lam) Against the Activity and Capacity of Phagocytosis of Macrofag Cells and the Percentage of Leukosit Cells of White Mice. Pharmacogn. J. 2021, 13, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q.; Liu, G.; Fu, X. Structural Characterization and Immune Enhancement Activity of a Novel Polysaccharide from Moringa oleifera Leaves. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 115897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangnoi, C.; Chingsuwanrote, P.; Praengamthanachoti, P.; Svasti, S.; Tuntipopipat, S. Moringa oleifera Pod Inhibits Inflammatory Mediator Production by Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Murine Macrophage Cell Lines. Inflammation 2012, 35, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, I.; Rifa’i, M. In Vitro Immunomodulatory Activity of Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf to the CD4+, CD8+ and B220+ Cells in Mus Musculus. J. Exp. Life Sci. 2014, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hong, Z.-S.; Xie, J.; Wang, X.-F.; Dai, J.-J.; Mao, J.-Y.; Bai, Y.-Y.; Sheng, J.; Tian, Y. Moringa oleifera Lam. Peptide Remodels Intestinal Mucosal Barrier by Inhibiting JAK-STAT Activation and Modulating Gut Microbiota in Colitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 924178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Yuan, G.; Jiang, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, L. Characterization of Moringa oleifera Roots Polysaccharide MRP-1 with Anti-Inflammatory Effect. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunthayung, K.; Bhawamai, S. Polyphenol Compounds of Freeze-Dried Moringa oleifera Lam Pods and Their Anti-Inflammatory Effects on RAW 264.7 Macrophages Stimulated with Lipopolysaccharide. Bioact. Compd. Health Dis. 2024, 7, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Arulselvan, P.; Tan, W.S.; Gothai, S.; Muniandy, K.; Fakurazi, S.; Esa, N.M.; Alarfaj, A.A.; Kumar, S.S. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Ethyl Acetate Fraction of Moringa oleifera in Downregulating the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages. Molecules 2016, 21, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praengam, K.; Muangnoi, C.; Dawilai, S.; Awatchanawong, M.; Tuntipopipat, S. Digested Moringa oleifera Boiled Pod Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Caco-2 Cells. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2015, 21, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetragoon, T.; Pankla Sranujit, R.; Noysang, C.; Thongsri, Y.; Potup, P.; Suphrom, N.; Nuengchamnong, N.; Usuwanthim, K. Bioactive Compounds in Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaves Inhibit the Pro-Inflammatory Mediators in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. Molecules 2020, 25, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldayel, T.S.; Gad El Hak, H.N.; Nafie, M.S.; Saad, R.; Abdelrazek, H.M.A.; Kilany, O.E. Evaluation of Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Anticancer Activities and Molecular Docking of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil Extract against Experimental Model of Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma in Swiss Female Albino Mice. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Xie, S.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Song, S. Moringa oleifera Leaves Protein Suppresses T-Lymphoblastic Leukemogenesis via MAPK/AKT Signaling Modulation of Apoptotic Activation and Autophagic Flux Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1546189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, S.K.; Khwaldeh, A.; Alsarhan, A.A.; Yousef, I.; Al-Shdefat, R.; Shoiab, A.; Ababneh, S. The Modulatory Effects of Statins, Vitamin E, and Moringa oleifera Extract on CD3 Expression in Ribociclib-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Acta Inf. Med. 2025, 33, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluan, J.C.; Zubair, M.S.; Ramadani, A.P.; Hayati, F. Narrative Review: Potential of Flavonoids from Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) Leaves as Immunomodulators. J. Farm. Galen. Galen. J. Pharm. 2023, 9, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, A.K.; Lalitha, C.M.V.N.; Shanmugam, M.; Subramanian, G.; Natarajan, J.; Selvaraj, J. Plant Derived Immunomodulators; A Critical Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nfambi, J.; Bbosa, G.S.; Sembajwe, L.F.; Gakunga, J.; Kasolo, J.N. Immunomodulatory Activity of Methanolic Leaf Extract of Moringa oleifera in Wistar Albino Rats. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 26, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.K.; Albalawi, S.M.; Athar, M.T.; Khan, A.Q.; Al-Shahrani, H.; Islam, M. Moringa oleifera as an Anti-Cancer Agent against Breast and Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Tang, Q.; Wu, W.-T.; Huang, X.-A.; Xu, Q.; Rong, G.-L.; Chen, S.; Song, J.-P. Three Constituents of Moringa oleifera Seeds Regulate Expression of Th17-Relevant Cytokines and Ameliorate TPA-Induced Psoriasis-Like Skin Lesions in Mice. Molecules 2018, 23, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, H. Potential Allergenicity Response to Moringa oleifera Leaf Proteins in BALB/c Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuryandari, M.R.E.; Atho’illah, M.F.; Laili, R.D.; Fatmawati, S.; Widodo, N.; Widjajanto, E.; Rifa’i, M. Lactobacillus Plantarum FNCC 0137 Fermented Red Moringa oleifera Exhibits Protective Effects in Mice Challenged with Salmonella Typhi via TLR3/TLR4 Inhibition and down-Regulation of Proinflammatory Cytokines. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2022, 13, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladia, R.E.; Ampode, K.M.B. Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) Pod Meal: Nutrient Analysis and Its Effect on the Growth Performance and Cell-Mediated Immunity of Broiler Chickens. J. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 9, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Yasoob, T.B.; Khalid, A.R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hang, S. Liver Transcriptome of Rabbits Supplemented with Oral Moringa oleifera Leaf Powder under Heat Stress Is Associated with Modulation of Lipid Metabolism and Up-Regulation of Genes for Thermo-Tolerance, Antioxidation, and Immunity. Nutr. Res. 2022, 99, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minutolo, A.; Potestà, M.; Roglia, V.; Cirilli, M.; Iacovelli, F.; Cerva, C.; Fokam, J.; Desideri, A.; Andreoni, M.; Grelli, S. Plant microRNAs from Moringa oleifera Regulate Immune Response and HIV Infection. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 620038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldi, Y.; Ramadhan, Z.L.; Dillasamola, D.; Alianta, A.A. The Activities of Moringa oleifera Lam Leaf Extract on Specific Cellular Immune of Albino Male Mice Induced by the COVID-19 Antigen. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 9, 2421–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, S.; Lal, M.; Rahaman, S.B.; Debnath, U.; Rawal, R.K. Computational Screening of Moringa oleifera Compounds for Immunomodulatory Targets: Identification and Validation of Core Genes. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 185, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Xi, C.; Feng, D.; Song, S. Analysis of the Sensitization Activity of Moringa oleifera Leaves Protein. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1509343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Li, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.H. Characterization of a Novel Polysaccharide from the Leaves of Moringa oleifera and Its Immunostimulatory Activity. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 49, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Lu, X.; Yang, S.; Zou, Y.; Zeng, F.; Xiong, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, W. The Anti-Inflammatory Activity of GABA-Enriched Moringa oleifera Leaves Produced by Fermentation with Lactobacillus Plantarum LK-1. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1093036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ma, L.; Wen, Y.; Xie, J.; Yan, L.; Ji, A.; Zeng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Sheng, J. Crude Polysaccharide Extracted from Moringa oleifera Leaves Prevents Obesity in Association with Modulating Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 861588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husien, H.M.; Rehman, S.U.; Duan, Z.; Wang, M. Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaf Polysaccharide on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1409026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Peng, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, H. The Structural Characterization of Polysaccharides from Three Cultivars of Moringa oleifera Lam. Root and Their Effects on Human Intestinal Microflora. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Tian, H.; Liang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Deng, M.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, B. Moringa oleifera Polysaccharide Regulates Colonic Microbiota and Immune Repertoire in C57BL/6 Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 198, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Husien, H.; Peng, W.; Su, H.; Zhou, R.; Tao, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, M.; Bo, R.; Li, J. Moringa oleifera Leaf Polysaccharide Alleviates Experimental Colitis by Inhibiting Inflammation and Maintaining Intestinal Barrier. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1055791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.R.; Yasoob, T.B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hang, S. Dietary Moringa oleifera Leaf Powder Improves Jejunal Permeability and Digestive Function by Modulating the Microbiota Composition and Mucosal Immunity in Heat Stressed Rabbits. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 80952–80967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Liang, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Deng, M.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; Sun, B. Moringa oleifera Polysaccharides Regulates Caecal Microbiota and Small Intestinal Metabolic Profile in C57BL/6 Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Fu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Q. In Vitro Digestibility and Prebiotic Activities of a Bioactive Polysaccharide from Moringa oleifera Leaves. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, H.; Gao, C.; Tian, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, B. Moringa oleifera Leaf Polysaccharide Regulates Fecal Microbiota and Colonic Transcriptome in Calves. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husien, H.M.; Peng, W.; Essa, M.O.A.; Adam, S.Y.; Ur Rehman, S.; Ali, R.; Saleh, A.A.; Wang, M.; Li, J. The Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Polysaccharides Extracted from Moringa oleifera Leaves on IEC6 Cells Stimulated with Lipopolysaccharide In Vitro. Animals 2024, 14, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, B. Comprehensive Analysis of Microbiome, Metabolome and Transcriptome Revealed the Mechanisms of Moringa oleifera Polysaccharide on Preventing Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricosta, L.; Silvestro, S.; Pizzicannella, J.; Diomede, F.; Bramanti, P.; Trubiani, O.; Mazzon, E. Transcriptomic Analysis of Stem Cells Treated with Moringin or Cannabidiol: Analogies and Differences in Inflammation Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Xu, Y.-M.; Lau, A.T.Y. Anti-Cancer and Medicinal Potentials of Moringa Isothiocyanate. Molecules 2021, 26, 7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuellar-Núñez, M.L.; De Mejia, E.G.; Loarca-Piña, G. Moringa oleifera Leaves Alleviated Inflammation through Downregulation of IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α in a Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Model. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleo, I.V.; Gao, Q.; Liu, B.; Sun, C.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Shan, F.; Xiong, Z.; Bo, L.; Song, C. Effects of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract on Growth Performance, Physiological and Immune Response, and Related Immune Gene Expression of Macrobrachium Rosenbergii with Vibrio Anguillarum and Ammonia Stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 89, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.; Huang, H.-T.; Liao, Z.-H.; Chen, B.-Y.; Wu, Y.-S.; Lin, Y.-J.; Nan, F.-H. Moringa oleifera Leaves’ Extract Enhances Nonspecific Immune Responses, Resistance against Vibrio Alginolyticus, and Growth in Whiteleg Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Animals 2021, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.A.; El-Mleeh, A.A.; Hamad, R.T.; Abu-Alya, I.S.; El-Hewaity, M.H.; Elbestawy, A.R.; Elbagory, A.M.; Sayed-Ahmed, A.S.; Abd Eldaim, M.A.; Elshabrawy, O.I. Immunostimulant Potential of Moringa oleifera Leaves Alcoholic Extract versus Oregano Essential Oil (OEO) against Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression in Broilers Chicks. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Fang, X.; Bao, W.; Aqueous, M. Oleifera Leaf Extract Alleviates DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice through Suppression of Inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailaja, B.S.; Aita, R.; Maledatu, S.; Ribnicky, D.; Verzi, M.P.; Raskin, I. Moringa Isothiocyanate-1 Regulates Nrf2 and NF-κB Pathway in Response to LPS-Driven Sepsis and Inflammation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman-Lara, E.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Ávila-Manrique, S.; Dorado-López, C.; Villalva, M.; Jaime, L.; Santoyo, S.; Martínez-Sánchez, C.E. In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Bioaccessibility of Ethanolic Extracts from Mexican Moringa oleifera Leaf. Foods 2024, 13, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetragoon, T.; Daowtak, K.; Thongsri, Y.; Potup, P.; Calder, P.C.; Usuwanthim, K. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of 3-Hydroxy-β-Ionone from Moringa oleifera: Decreased Transendothelial Migration of Monocytes Through an Inflamed Human Endothelial Cell Monolayer by Inhibiting the IκB-α/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Naeem, H.; Batool, M.; Imran, M.; Hussain, M.; Mujtaba, A.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Ghoneim, M.M.; et al. Antioxidant, Anticancer, and Anti-inflammatory Potential of Moringa Seed and Moringa Seed Oil: A Comprehensive Approach. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 6157–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias-Pereira, R.; Camayoc, P.; Raskin, I. Isothiocyanate-Rich Moringa Seed Extract Activates SKN-1/Nrf2 Pathway in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, A.A.M.A.; Gharib, A.A.E.-A.; Abdelgalil, S.Y.; AbdAllah, H.M.; Elmowalid, G.A. Immunomodulatory, Antioxidant, and Growth-Promoting Activities of Dietary Fermented Moringa oleifera in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromus niloticus) with in-Vivo Protection against Aeromonas Hydrophila. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, J.; Gong, J.; Peng, W.; Yu, C.; Huai, Y.; Chen, C.; Bo, R.; Liu, M.; Li, J. Composition and Anti-Colitis Efficacy Analysis of Ethanol and Aqueous Extraction of Moringa oleifera Leaves. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetragoon, T.; Sranujit, R.P.; Noysang, C.; Thongsri, Y.; Potup, P.; Somboonjun, J.; Maichandi, N.; Suphrom, N.; Sangouam, S.; Usuwanthim, K. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. and Cyanthillium Cinereum (Less) H. Rob. Lozenges in Volunteer Smokers. Plants 2021, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Prieto, L.E.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Vicente-Castro, I.; Heredia, C.; González-Romero, E.A.; Martín-Ridaura, M.D.C.; Ceinos, M.; Picón, M.J.; Marcos, A.; Nova, E. Effects of Moringa oleifera Lam. Supplementation on Inflammatory and Cardiometabolic Markers in Subjects with Prediabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, N.A. Effect of Moringa Leaf Extract on Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients; Clinicaltrials.gov: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022.

- Asare, B.; Selorm Segbefia, P.; Awuku-Larbi, R.; Asema Asandem, D.; Brenko, T.; Bentum-Ennin, L.; Osei, F.; Teye-Adjei, D.; Agyekum, G.; Akuffo, L. Immunomodulatory Effect of Moringa oleifera and Phyllanthus niruri extracts on Anti-HBV Cytokine Production by Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Open Res. Eur. 2025, 5, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambo, A.; Moodley, I.; Babashani, M.; Babalola, T.K.; Gqaleni, N. A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial to Examine the Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaf Powder Supplementation on the Immune Status and Anthropometric Parameters of Adult HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in a Resource-Limited Setting. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G.R.; Mohana, T.; Athesh, K.; Hillary, V.E.; Vasconcelos, A.B.S.; Farias de Franca, M.N.; Montalvão, M.M.; Ceasar, S.A.; Jothi, G.; Sridharan, G.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Natural Products Modulate Interleukins and Their Related Signaling Markers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 13, 1408–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Shi, S.-R.; Ma, C.-N.; Lin, Y.-P.; Song, W.-G.; Guo, S.-D. Natural Products in Atherosclerosis Therapy by Targeting PPARs: A Review Focusing on Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1372055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sahardi, N.F.N.; Makpol, S. Suppression of Inflamm-Aging by Moringa oleifera and Zingiber Officinale Roscoe in the Prevention of Degenerative Diseases: A Review of Current Evidence. Molecules 2023, 28, 5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiș, A.; Noubissi, P.A.; Pop, O.-L.; Mureșan, C.I.; Fokam Tagne, M.A.; Kamgang, R.; Fodor, A.; Sitar-Tăut, A.-V.; Cozma, A.; Orășan, O.H.; et al. Bioactive Compounds in Moringa oleifera: Mechanisms of Action, Focus on Their Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Plants 2023, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzashokouhi, A.H.; Rezaee, R.; Omidkhoda, N.; Karimi, G. Natural Compounds Regulate the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β Pathway in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Cycle 2023, 22, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, L.; Xu, M.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, K. Moringin Alleviates DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Mice by Regulating Nrf2/NF-κB Pathway and PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 134, 112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.G.; Chang, S.N.; Park, S.M.; Hwang, B.S.; Kang, S.-A.; Kim, K.S.; Park, J.G. Moringa oleifera Mitigates Ethanol-Induced Oxidative Stress, Fatty Degeneration and Hepatic Steatosis by Promoting Nrf2 in Mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 100, 154037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, O.A.; Akhigbe, T.M.; Akhigbe, R.E.; Alabi, B.A.; Gbolagun, O.T.; Taiwo, M.E.; Fakeye, O.O.; Yusuf, E.O. Methanolic Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract Protects against Epithelial Barrier Damage and Enteric Bacterial Translocation in Intestinal I/R: Possible Role of Caspase 3. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 989023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftah, A.H.; Alhelfi, N.; Al Salait, S.K.; Altemimi, A.B.; Tabandeh, M.R.; Tsakali, E.; Van Impe, J.F.; Abd El-Maksoud, A.A.; Abedelmaksoud, T.G. Mitigation of Doxorubicin-Induced Liver Toxicity in Mice Breast Cancer Model by Green Tea and Moringa oleifera Combination: Targeting Apoptosis, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 124, 106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.M.; Helmy, R.M.A.; Osman, A.; Ahmed, F.A.G.; Kotb, G.A.M.; El-Fattah, A.H.A. The Potential Effect of Moringa oleifera Ethanolic Leaf Extract against Oxidative Stress, Immune Response Disruption Induced by Abamectin Exposure in Oreochromis niloticus. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 58569–58587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liga, S.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Avram, Ș.; Minda, D.I.; Vlase, A.-M.; Muntean, D.; Vlase, L.; Moacă, E.-A.; Danciu, C. Comparative Analysis of Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaves Ethanolic Extracts: Effects of Extraction Methods on Phytochemicals, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and In Ovo Profile. Plants 2025, 14, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Li, F.; Jiao, J.; Qian, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Zhou, T.; Wu, H.; Kong, X. Quercetin, a Natural Flavonoid, Protects against Hepatic Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury via Inhibiting Caspase-8/ASC Dependent Macrophage Pyroptosis. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 70, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, R.; Buhe, A.; Xu, B. Quercetin Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Hepatic Inflammation by Modulating Autophagy and Necroptosis. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsaros, I.; Sotiropoulou, M.; Vailas, M.; Kapetanakis, E.I.; Valsami, G.; Tsaroucha, A.; Schizas, D. Quercetin’s Potential in MASLD: Investigating the Role of Autophagy and Key Molecular Pathways in Liver Steatosis and Inflammation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Tang, Y.; Song, S.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y. A Detailed Overview of Quercetin: Implications for Cell Death and Liver Fibrosis Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1389179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhai, J.; Tao, L.; Sun, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J. Quercetin Attenuates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Apoptosis to Protect INH-Induced Liver Injury via Regulating SIRT1 Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 85, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guon, T.E.; Chung, H.S. Moringa oleifera Fruit Induce Apoptosis via Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Human Melanoma A2058 Cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, G.B.; Olowoparija, S.F.; Olayemi, J.O.; Olayinka, E. Effect of Ethanol Extract of Moringa oleifera Leaves on T-Cell Proliferation. West. J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni, E.O.; Adedeji, A.L.; Akanni, R.A.; Oloke, J.K. Up-Regulation of TNF-α by Ethanol Extract of Moringa oleifera in Benzene-Induced Leukemic Wister Rat: A Possible Mechanism of Anticancer Property. Res. Rev. J. Oncol. Haematol. 2014, 3, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Abutu, P.; Amuda, O.; Osinaya, O.; Babatunde, B. Regulatory Activity of Ethanol Leaves Extract of Moringa oleifera on Benzene Induced Leukemia in Wister Rat Using TNF-α Analysis. Am. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Van Pham, A.T.; Luong, M.H.; Dinh, H.T.T.; Mai, T.P.; Trinh, Q.V.; Luong, L.H. Immunostimulatory Effect of Moringa oleifera Extracts on Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppressed Mice. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2021, 27, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, A.K.M.; Hasan, I.; Chakrabortty, A.; Zaman, S.; Islam, S.S.; Ahmed, F.R.S.; Kabir, K.A.; Nurujjaman, M.; Uddin, M.B.; Alam, M.T. Moringa oleifera Seed Lectin Inhibits Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma Cell Growth by Inducing Apoptosis through the Regulation of Bak and NF-κB Gene Expression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, S.S.; Chuturgoon, A.A.; Ghazi, T. Moringa oleifera Lam Leaf Extract Stimulates NRF2 and Attenuates ARV-Induced Toxicity in Human Liver Cells (HepG2). Plants 2023, 12, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailaja, B.S.; Hassan, S.; Cohen, E.; Tmenova, I.; Farias-Pereira, R.; Verzi, M.P.; Raskin, I. Moringa Isothiocyanate-1 Inhibits LPS-Induced Inflammation in Mouse Myoblasts and Skeletal Muscle. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Vazquez, E.Y.; Gómez-Cansino, R.; Marcelino-Pérez, G.; Jiménez-López, D.; Quintas-Granados, L.I. Unveiling the Miracle Tree: Therapeutic Potential of Moringa oleifera in Chronic Disease Management and Beyond. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, B.H.; Hoang, N.S.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Ho, N.Q.C.; Le, T.L.; Doan, C.C. Phenolic Extraction of Moringa oleifera Leaves Induces Caspase-Dependent and Caspase-Independent Apoptosis through the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Activation of Intrinsic Mitochondrial Pathway in Human Melanoma Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, R.; Ahmed, A.; Wei, L.; Saeed, H.; Islam, M.; Ishaq, M. The Anticancer Potential of Chemical Constituents of Moringa oleifera Targeting CDK-2 Inhibition in Estrogen Receptor Positive Breast Cancer Using in-Silico and in Vitro Approches. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Zha, D.; Sang, Y.; Tao, J.; Cheng, Y. Moringa oleifera Mediated Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anti-Cancer Activity against A549 Cell Line of Lung Cancer through ROS/Mitochondrial Damage. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1521089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaavyaunni; Antony, S.; Chanthini, K.M.-P. Biogenically Synthesized Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract-Derived Silver Nanoparticles Exhibit Potent Antimicrobial and Anticancer Effects via Oxidative Stress and Apoptotic Pathways in AGS Gastric Cancer Cells. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, P.K.; Shukla, A.; Singh, R.K.; Patel, A.K.; Yadav, L.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Kaushalendra; Acharya, A. Moringa oleifera L. Leaf Extract Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Mitochondrial Apoptosis in Dalton’s Lymphoma: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 302, 115849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shalabi, R.; abdul Samad, N.; Al-Deeb, I.; Joseph, J.; Abualsoud, B.M. Assessment of Antiangiogenic and Cytotoxic Effects of Moringa oleifera Silver Nanoparticles Using Cell Lines. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2024, 12, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choirunnisa, N.L.; Kezia, D.C.; Permana, A.Z.; Malek, N.A.N.N.; Nurkolis, F.; Permatasari, H.K. Modulation of pAKT and NF-κB Pathways by Moringa oleifera Silver Nanoparticles: Inducing Apoptosis in Cervical Cancer Cells. CyTA J. Food 2025, 23, 2543878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Allah, R.S.; Ahmmed, N.H.; Walaa, A.; Heibashy, D.M. The Curative Role of Moringa Leaf Extract Nanomaterial and Low Doses of Gamma Irradiation on Ehrlich Carcinoma Bearing Mice. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci. 2025, 14, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, N.S.C.; Kei, W.W. Anti-Angiogenic Screening of Moringa oleifera Leaves Extract Using Chorioallantonic Membrane Assay. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 31, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, H.; Firdaus, S.R.A.; Sholeh, M.; Endharti, A.T.; Taufiq, A.; Malek, N.A.N.N.; Permatasari, H.K. Moringa oleifera Leaf Powder—Silver Nanoparticles (MOLP-AgNPs) Efficiently Inhibit Metastasis and Proliferative Signaling in HT-29 Human Colorectal Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunica, E.R.; Yang, S.; Coulter, A.; White, C.; Kirwan, J.P.; Gilmore, L.A. Moringa oleifera Seed Extract Concomitantly Supplemented with Chemotherapy Worsens Tumor Progression in Mice with Triple Negative Breast Cancer and Obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armagan, G.; Sevgili, E.; Gürkan, F.T.; Köse, F.A.; Bilgiç, T.; Dagcı, T.; Saso, L. Regulation of the Nrf2 Pathway by Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β in MPP+-Induced Cell Damage. Molecules 2019, 24, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourebaba, L.; Komakula, S.S.B.; Weiss, C.; Adrar, N.; Marycz, K. The PTP1B Selective Inhibitor MSI-1436 Mitigates Tunicamycin-Induced ER Stress in Human Hepatocarcinoma Cell Line through XBP1 Splicing Modulation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wu, N.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Li, C.; Jiang, B.; Wang, H.; Shi, D. Inhibition of PTP1B Blocks Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Targeting the PKM2/AMPK/mTOC1 Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagoel, L.; Vexler, A.; Kalich-Philosoph, L.; Earon, G.; Ron, I.; Shtabsky, A.; Marmor, S.; Lev-Ari, S. Combined Effect of Moringa oleifera and Ionizing Radiation on Survival and Metastatic Activity of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1534735419828829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aja, P.M.; Agu, P.C.; Ezeh, E.M.; Awoke, J.N.; Ogwoni, H.A.; Deusdedit, T.; Ekpono, E.U.; Igwenyi, I.O.; Alum, E.U.; Ugwuja, E.I.; et al. Prospect into Therapeutic Potentials of Moringa oleifera Phytocompounds against Cancer Upsurge: De Novo Synthesis of Test Compounds, Molecular Docking, and ADMET Studies. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Desai, B.M.A.; Biswas, P. Multi-Ligand Simultaneous Docking Analysis of Moringa oleifera Phytochemicals Reveals Enhanced BCL-2 Inhibition via Synergistic Action. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (IBIOMED), Bali, Indonesia, 23–25 October 2024; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadresha, K.; Thakore, V.; Brahmbhatt, J.; Upadhyay, V.; Jain, N.; Rawal, R. Anticancer Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaves Extract against Lung Cancer Cell Line via Induction of Apoptosis. Adv. Cancer Biol. Metastasis 2022, 6, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICTRP Search Portal. Available online: https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=CTRI/2022/02/040594 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Tshingani, K.; Donnen, P.; Mukumbi, H.; Duez, P.; Dramaix-Wilmet, M. Impact of Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf Powder Supplementation versus Nutritional Counseling on the Body Mass Index and Immune Response of HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy: A Single-Blind Randomized Control Trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprioku, J.S.; Robinson, O.; Obianime, A.W.; Tamuno, I. Moringa Supplementation Improves Immunological Indices and Hematological Abnormalities in Seropositive Patients Receiving HAARTs. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoi, D.; Upadhaya, P.; Barbhuiya, S.N.; Giri, A.; Giri, S. Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera Exhibit Potential Anticancer Activity and Can Be Used as a Possible Cancer Therapeutic Agent: A Study Involving In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jaja-Chimedza, A.; Merrill, D.; Mendes, O.; Raskin, I. A 14-Day Repeated-Dose Oral Toxicological Evaluation of an Isothiocyanate-Enriched Hydro-Alcoholic Extract from Moringa oleifera Lam. Seeds in Rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweerutchana, R.; Lumlerdkij, N.; Vannasaeng, S.; Akarasereenont, P.; Sriwijitkamol, A. Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaf Capsules on Glycemic Control in Therapy-Naïve Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Randomized Placebo Controlled Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 6581390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.; Shaari, M.R.; Ahmad Sayuti, N.S.; Reduan, F.H.; Sithambaram, S.; Mohamed Mustapha, N.; Shaari, K.; Hamzah, H.B. Moringa oleifera Hydorethanolic Leaf Extract Induced Acute and Sub-Acute Hepato-Nephrotoxicity in Female ICR-Mice. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211004272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, M.L.; Hallarou, M.E.; Halidou, M.D.; Maiga, D.A.; Bahwere, P.; Salimata, W.; Castetbon, K.; Wilmet-Dramaix, M.; Donnen, P. Effect of Moringa Supplementation in the Management of Moderate Malnutrition in Children under 5 Receiving Ready-to-Use Supplementary Foods in Niger: A Randomized Clinical Trial. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 071–086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajuju Malla, J.; Ochola, S.; Ogada, I.; Munyaka, A. Effect of Moringa oleifera Fortified Porridge Consumption on Protein and Vitamin A Status of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Nairobi, Kenya: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.R.G.; Costa, W.K.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; Soares, L.A.L.; Napoleão, T.H.; Paiva, P.M.G.; de Oliveira, A.M. 13-Week Repeated-Dose Toxicity Study of Optimized Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera Leaves in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 335, 118637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedapo, A.A.; Mogbojuri, O.M.; Emikpe, B.O. Safety Evaluations of the Aqueous Extract of the Leaves of Moringa oleifera in Rats. J. Med. Plants Res. 2009, 3, 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu, D.; Rwuaan, J.S.; Sani, D.; Nwannenna, A.I.; Njoku, C.O.; Mustapha, A.R.; Peter, I.D. Evaluation of Safety, Proximate and Efficacy of Graded Dose of Moringa oleifera Aqueous Seed Extract as Supplement That Improve Live-Body Weight and Scrotal Circumference in Yankasa Ram. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2020, 10, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Pacheco, M.; Rojas-Armas, J.P.; Ortiz-Sánchez, J.M.; Arroyo-Acevedo, J.L.; Justil-Guerrero, H.J.; Martínez-Heredia, J.T. Assessment of Oral Toxicity of Moringa oleifera Lam Aqueous Extract and Its Effect on Gout Induced in a Murine Model. Vet. World 2024, 17, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.H.; Gebru, G.; Debella, A.; Makonnen, E.; Asefa, M.; Woldekidan, S.; Abebe, A.; Lengiso, B.; Bashea, C. Prenatal Developmental Toxicity Study of Herbal Tea of Moringa stenopetala and Mentha spicata Leaves Formulation in Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajar, A.; Abdelmounaim, B.; Hamid, K.; Jaouad, L.; Abdelfattah, A.B.; Majda, B.; Loubna, E.Y.; Mohammed, L.; Rachida, A.; Abderrahman, C. Developmental Toxicity of Moringa oleifera and Its Effect on Postpartum Depression, Maternal Behavior and Lactation. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 171, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S.S.; Suliman, A.A.; Fathy, K.; Sedik, A.A. Ovario-Protective Effect of Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract against Cyclophosphamide-Induced Oxidative Ovarian Damage and Reproductive Dysfunction in Female Rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1054. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulahi, S.K.; Dada, E.O.; Adebayo, R.O. Histopathological Effects of Seed Oil of Moringa oleifera Lam. on Albino Mice Infected with Plasmodium Berghei (NK65). Adv. J. Grad. Res. 2022, 11, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghama, O.E.; Timothy, O.; Gabriel, B.O.; Abaku, S.N. 21 Days Effects of Ethanol Root Extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. on Kidney and Liver Functions in Wistar Rats. Trop. J. Chem. 2025, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.H.; Hagos, A.D.; Dimsu, G.G.; Eshetu, E.M.; Tola, M.A.; Admas, A.; Gelagle, A.A.; Tullu, B.L. Subchronic Toxicity Study of Herbal Tea of Moringa stenopetala (Baker f.) Cudof. and Mentha spicata L. Leaves Formulation in Wistar Albino Rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohs, S.J.; Hartman, M.J. Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Moringa oleifera. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanikachalam, P.V.; Ramesh, K.; Hydar, M.I.; Dhalapathy, V.V.; Devaraji, M. Therapeutic Potential of Moringa oleifera Lam. in Metabolic Disorders: A Molecular Overview. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2025, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, H.; Nakayama, S.M.M.; Kataba, A.; Toyomaki, H.; Doya, R.; Beyene Yohannes, Y.; Ikenaka, Y.; Ishizuka, M. Does Moringa oleifera Affect Element Accumulation Patterns and Lead Toxicity in Sprague–Dawley Rats? J. Funct. Foods 2022, 97, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, J.O.; Aworunse, O.S.; Oyesola, O.L.; Akinnola, O.O.; Obembe, O.O. A Systematic Review of Pharmacological Activities and Safety of Moringa oleifera. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2020, 9, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwanis, F.M.; Abdelaty, H.S.; Saleh, S.A. Exploring the Multifaceted Uses of Moringa oleifera: Nutritional, Industrial and Agricultural Innovations in Egypt. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, H.; Soror, E.; El-Asely, A.; El-Gawad, E.A.; Abbass, A. Dietary Supplementation of Moringa Leaf Meal for Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus: Effect on Growth and Stress Indices. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2019, 45, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, G.R.; Abdel-Rahim, M.M.; Lotfy, A.M.; Fayed, W.M.; Shehata, A.I.; El Basuini, M.F.; Elwan, R.I.; Al-absawey, M.A.; Elhetawy, A.I.G. Long Term Dietary Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract to Florida Red Tilapia Oreochromis Sp Improves Performance Immunity Maturation and Reproduction in Saltwater. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofulue, O.O.; Ebomoyi, M.I. Acute Toxicity Test of Alkaloid Fraction of Moringa oleifera Leaf and Its Effect on Reproductive Hormones of Pregnant Wistar Rats. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2023, 27, 2235–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilaoui, M.; Ait Mouse, H.; Zyad, A. Update and New Insights on Future Cancer Drug Candidates from Plant-Based Alkaloids. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 719694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, M.; Li, N.; Chan, W.Y.; Lin, G. Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid-Induced Hepatotoxicity Associated with the Formation of Reactive Metabolite-Derived Pyrrole–Protein Adducts. Toxins 2021, 13, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; Xiang, Q.; Wen, J.; Huang, Y.; Rao, C.; Chen, Y. A Toxicological Review of Alkaloids. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 47, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagrera, A.; Montenegro, T.; Borrego, L. Toxicodermia por Moringa oleifera. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021, 112, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Part Used | Form of Application | Model/System | Key Mechanistic Insights | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Leaf polysaccharide fraction | Lewis lung carcinoma (C57BL/6 mice, oral). In vitro bone marrow-derived macrophages | Activation of macrophage through toll-like receptor reprograms TAMs from M2 to M1 through TLR4, ↑ CXCL9/10, ↑ T-cell infiltration | [58,63] |

| Leaves | Oral administration | Rabbits exposed to heat stress | Enhancement of NK cell activity through up-regulation of perforin/granzyme secretion | [64,65,66] |

| Leaves | Purified protein fraction | Murine BMSCs (In vitro), followed by allogenic MLR and in vivo IgE measurement in mice | Activation and maturation of DCs via upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules and the secretion of cytokines and chemokines: ↑ CD80/CD86/MHCII; ↑ IL12 and TNF-α secretion; OX40L-TIM-4-CCL17/22 axis drives Th2 polarization; enhanced T-cell proliferation | [60,67,68] |

| Leaves | Oral administration | Diabetic-induced damage in male Wistar rats | Reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL6) and oxidative stress | [68] |

| Leaves | Topical ethanolic extract (10%) Moringa tea (oral drinking water) | Wistar rats with experimental burn wounds Restraint-stressed mice | Modulation of neutrophil migration/chemotaxis and enhancing phagocytosis | [59,69] |

| Leaves | Oral administration of ethanolic leaf extract at 10, 30 and 100 mg/Kg for 7 days | Staphylococcus aureus-challenged mice (mouse peritoneal macrophage) | ↑ Macrophage phagocytic activity and capacity; ↑ Neutrophile percentage | [70] |

| Leaves | Purified polysaccharide fraction | RAW 264.7 macrophages (in vitro) | Enhances the gene expression of antimicrobial peptides such as Mop3 through ↑ pinocytosis; ↑ ROS/NO; ↑ IL6; TNF-α and iNOS expression | [71] |

| Pods | Boiled extract | RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line | Inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, TNF-α); suppresses iNOS and COX-2 expression; decreases NO production | [72] |

| Leaves | Ethyl acetate fraction | LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages | Regulation of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines through the regulation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling cascades | [73] |

| Seeds | Purified peptide (sequence KETTTIVR) administered orally | Dextran Sulfate Sodium-induced colitis in mice | Modulates gut microbiota and metabolomic profiles, inhibits JAK-STAT signaling, and protects the intestinal barrier | [74] |

| Leaves | Ethanolic extract; oral and in vitro exposure | Swiss albino mice peritoneal macrophages; RAW 264.7 | Increase phagocytosis activity through activation of phagocytic receptors and engulfment efficiency | [70] |

| Roots | Hot water extract, ethanolic extract | LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages murine macrophage cell line | Inhibits NO and TNF-α production; decreases iNOS mRNA production | [75] |

| Pods | Freeze-dried pod polyphenol extract | RAW 264.7 macrophages (LPS-stimulation) | ↓ NO, ↓ TNF-α, strong anti-inflammatory effect | [76] |

| Leaves | Ethyl acetate extract (oral and in vitro) | RAW 264.7 macrophages | Inhibits NF-κB, suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL6); ↓ NO production | [77] |

| Pods | Digested boiled pod extract | Caco-2 cells (intestinal epithelial) | Suppressed inflammatory mediators; promoted epithelial anti-inflammatory defense | [78] |

| Leaves (aqueous and ethanolic extracts) | Oral administration and in vitro exposure | Various animal models (Wistar rats and BALB/c mice) and the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities via free radical scavenging and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α | [68,77,79,80] |

| Plant Part Used | Form of Application | Model/System | Key Mechanistic Insights | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Purified leaf protein | In vitro, Human T-lymphoblastic leukemia (Jurkat cells) | Modulation of T cell activation and proliferation through the regulation of T cell receptor signaling cascades | [60,81,82] |

| Leaves | Aqueous extract | In vitro, murine splenocyte culture | B-cell activation | [73] |

| Leaves | Methanolic extract | SRBC immunized Wistar rats | Antibody production via B cell receptor stimulation | [83,84,85] |

| Leaves | Ethanolic extract | Breast cancer cells (MD-MA-231) | ↓ of NF-κB and p65; Transcription factor modulation; ↓ cancer cell viability | [86] |

| Leaves | Topical application | Atopic dermatitis mouse model | Promote T-helper cell differentiation through modulation of Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cells responses | [61,67,87,88,89] |

| Leaves Leaf proteins | Oral administration Protein extract | Rabbits exposed to heat stress Murine BMDCs | Induction of Foxp3 expression and promotion of Treg cells | [60,64] |

| Pods | Pod meal (dietary inclusion) | Broiler chickens | Enhanced growth performance; improved cell-mediated immunity | [90] |

| Leaves | Leaf protein fraction or extract | BALB/c mice (intraperitoneal sensitization + oral exposure, allergy model); BMDCs (in vitro) and IgE induction after DCs transfer (in vivo) | Regulation of antigen presentation and processing | [60,88,91] |

| Leaves | Methanolic extract | Wistar albino rats | Stimulates neutrophil and lymphocyte function; Enhances humoral immunity; increases antigen-specific antibody secretion and WBC levels | [85] |

| Seeds | MicroRNA-enriched extract | Human PBMCs (HIV+) | Modulates T-cell differentiation and memory T-cell subsets; reduces HIV replication | [92] |

| Leaves | Protein extract (oral and in vitro) | BALB/c mice; Murine BMDCs | Induces IgE production and Th2 polarization; activates DC; modulates humoral immunity by enhancing the production of antigen-specific antibodies | [60,93,94,95] |

| Plant Part | Study Model | Dose/Duration | Key Findings/Safety Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seeds (hydroalcoholic extract) | Rats (14-day toxicity study) | 100–2000 mg/kg/day | No significant toxicological effects; normal hematological and biochemical parameters | [175] |

| Leaf capsules in T2DM patients | Humans: adults with T2DM (therapy naïve) | Nutritional dose, 4 weeks | Well tolerated; no hypoglycemia; renal (BUN, creatinine) and hepatic (AST, ALT) markers remained normal | [176] |

| Leaves (hydroethanolic extract) | Female ICR mice | Acute: 2000 mg/kg, single dose. Sub-acute: 125–1000 mg/kg daily for 28 days. | Acute: LD50 > 2000 mg/kg; signs of liver and kidney damage (increased AST, CK and creatinine; hepatic degeneration; renal necrosis). Sub-acute: moderate hepato-nephrotoxicity (hepatic and renal necrosis, sinusoidal dilatation; glomerulonephritis). Lower doses (125–500 mg/kg): relatively safe with minimal adverse effects. | [177] |

| Leaf powder | Humans: adults | 400 mg capsules, 6x daily (2.4 g/day); 12 weeks | Well tolerated; no adverse effects; kidney parameters (creatinine, urea), liver enzymes (AST, ALT), and hematological markers remained normal; decreased inflammatory parameters (CRP) and improved lipid profile (LDL-C, total cholesterol) | [124] |

| Leaf powder (added to RUSF) | Humans: children < 5 years with moderate malnutrition | Daily supplementation: 5 weeks for the Moringa group and 4 weeks for the placebo group. | No renal/hepatic toxicity reported; well tolerated | [178] |

| Leaf powder (10% fortified porridge) | Humans (observational study): children with cerebral palsy | Daily intake (3 months) | No serious adverse reactions or increased morbidity; improved nutritional (vitamin A and protein status) and immune markers | [179] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tilaoui, M.; El Karroumi, J.; Ait Mouse, H.; Zyad, A. Harnessing Moringa oleifera for Immune Modulation in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010263

Tilaoui M, El Karroumi J, Ait Mouse H, Zyad A. Harnessing Moringa oleifera for Immune Modulation in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010263

Chicago/Turabian StyleTilaoui, Mounir, Jamal El Karroumi, Hassan Ait Mouse, and Abdelmajid Zyad. 2026. "Harnessing Moringa oleifera for Immune Modulation in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010263

APA StyleTilaoui, M., El Karroumi, J., Ait Mouse, H., & Zyad, A. (2026). Harnessing Moringa oleifera for Immune Modulation in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010263