NSUN7 Regulates Sperm Flagella Formation at All Stages of Spermiogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

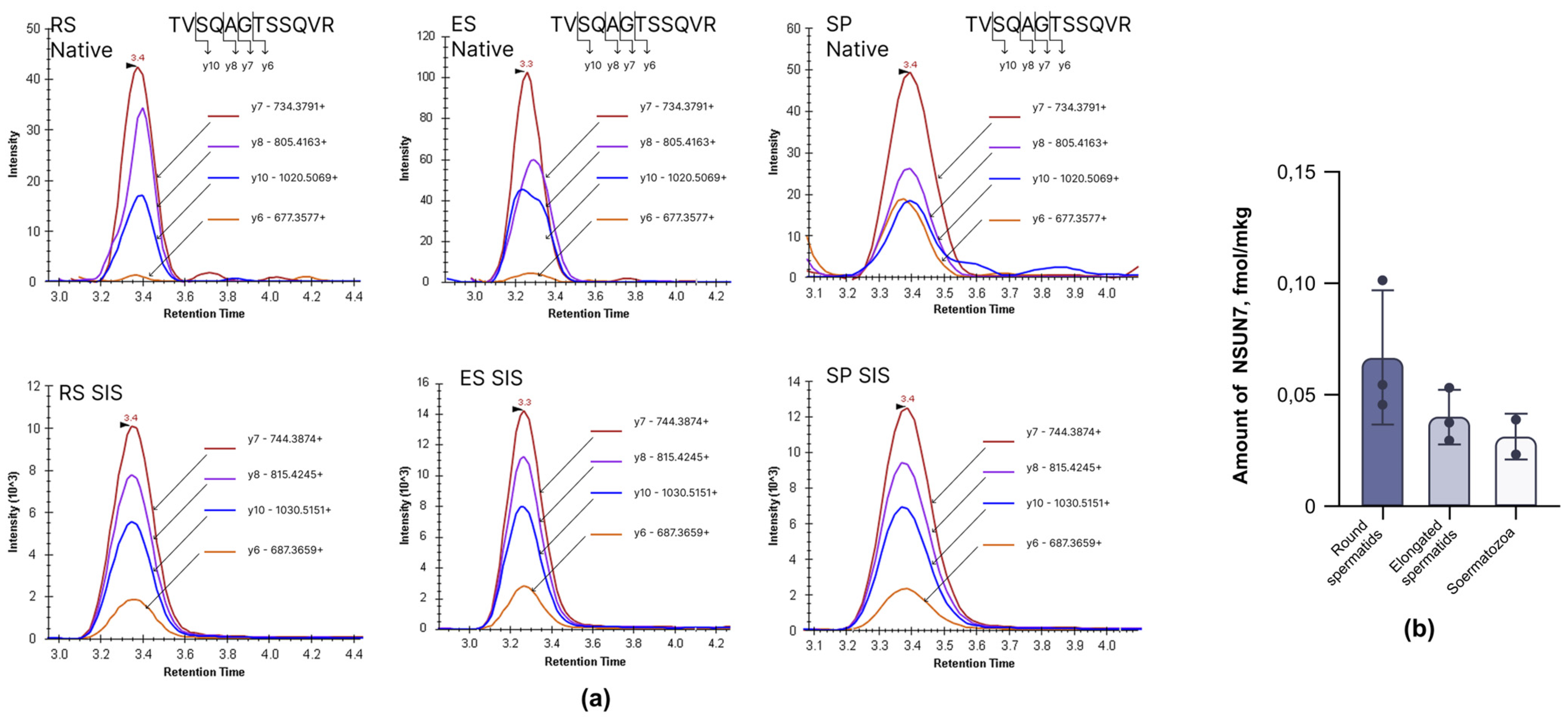

2.1. NSUN7 Is Present in Developing Spermatids and Mature Sperm

2.2. NSUN7 Influence on Transcription and Axoneme Associated Proteins in Round Spermatids

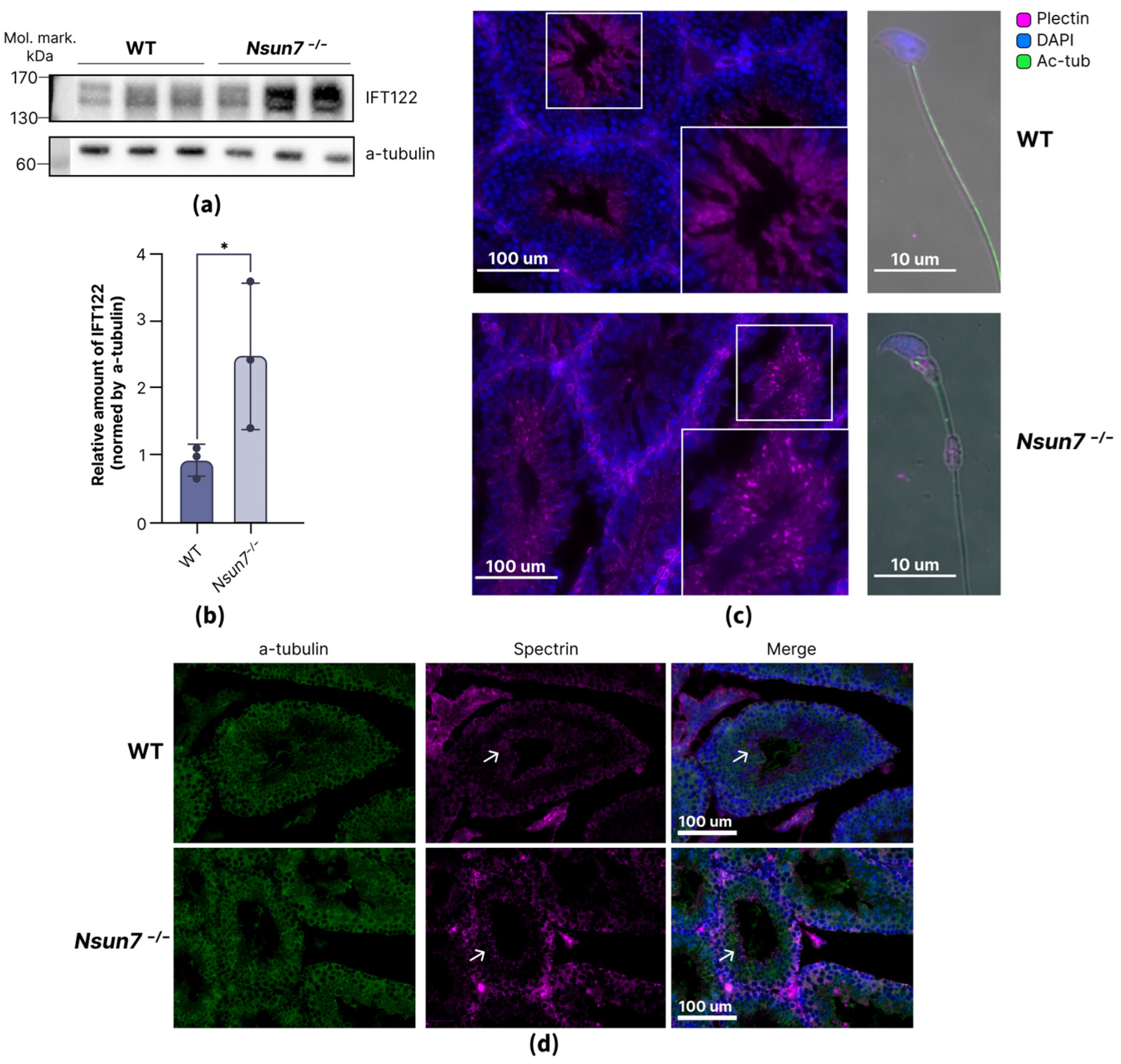

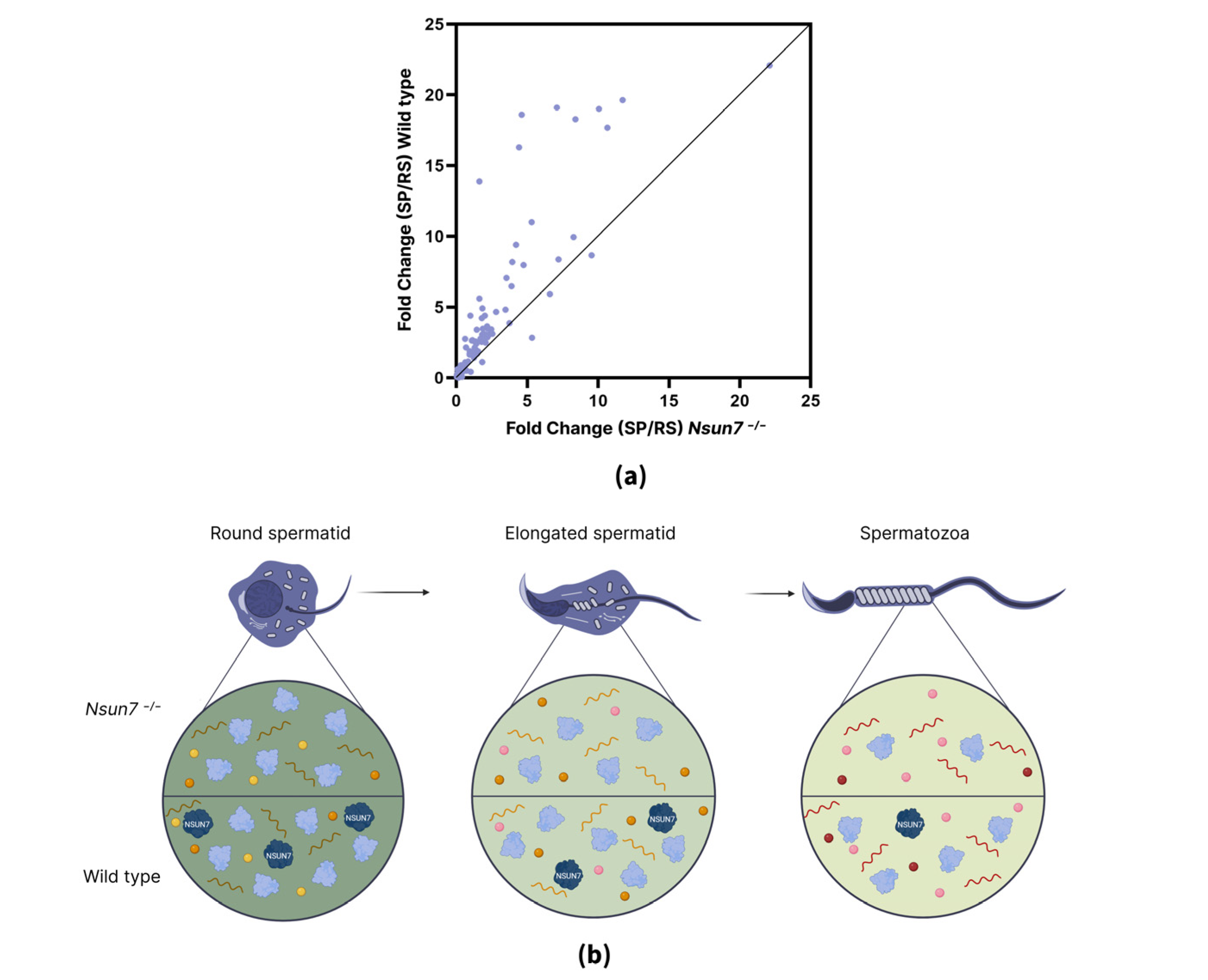

2.3. NSUN7 Influences Transport Proteins in Elongated Spermatids, While Proteome of Mature Sperm Remains Unaltered

2.4. NSUN7 May Regulate Protein Stabilization During Late Stages of Spermatogenesis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice Housing, Breeding, and Generation of Nsun7−/−

4.2. Sorting of Spermatogenic Cells

4.3. Proteome Analysis

4.4. Targeted Mass-Spectrometry Analysis of NSUN7

4.5. Immunohistochemistry

4.6. Immunocytochemistry

4.7. Immunoblotting

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griswold, M.D. Spermatogenesis: The Commitment to Meiosis. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; L’Hernault, S.W. Spermatogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R988–R994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, K.; Balhorn, R. Sperm Nuclear Protamines: A Checkpoint to Control Sperm Chromatin Quality. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2018, 47, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, M.H.; Fawcett, D.W. Studies on the Fine Structure of the Mammalian Testis. I. Differentiation of the Spermatids in the Cat (Felis Domestica). J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1955, 1, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Li, J.-H.; Tang, G.-C.; Xiao, S.-S. Transformation, Migration and Outcome of Residual Bodies in the Seminiferous Tubules of the Rat Testis. Andrologia 2017, 49, e12786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Wells, D.; Rusch, J.; Ahmad, S.; Marchini, J.; Myers, S.R.; Conrad, D.F. Unified Single-Cell Analysis of Testis Gene Regulation and Pathology in Five Mouse Strains. eLife 2019, 8, e43966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, H.; Yang, H.; Cheng, R.; Zheng, P.; Guo, R. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Round and Elongated Spermatids during Spermiogenesis in Mice. Biomed. Chromatogr. BMC 2020, 34, e4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Rong, B.; Li, L.; Lv, R.; Lan, F.; Tong, M.-H. The Histone Methyltransferase SETD2 Is Required for Expression of Acrosin-Binding Protein 1 and Protamines and Essential for Spermiogenesis in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 9188–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.-W.; Tan, L.-L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.-L.; Zheng, X.-M.; Chang, W.; Gao, L.; Wei, T.; Xu, D.-X.; Wang, H. Combination of High-Fat Diet and Cadmium Impairs Testicular Spermatogenesis in an m6A-YTHDF2-Dependent Manner. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irons, M.J.; Clermont, Y. Kinetics of Fibrous Sheath Formation in the Rat Spermatid. Am. J. Anat. 1982, 165, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oko, R.J.; Clermont, Y. Biogenesis of Specialized Cytoskeletal Elements of Rat Spermatozoa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991, 637, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Kuo, Y.-C.; Chiang, H.-S.; Kuo, P.-L. The Role of the Septin Family in Spermiogenesis. Spermatogenesis 2011, 1, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Oko, R.; Miranda-Vizuete, A. Developmental Expression of Spermatid-Specific Thioredoxin-1 Protein: Transient Association to the Longitudinal Columns of the Fibrous Sheath During Sperm Tail Formation. Biol. Reprod. 2002, 67, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Li, F.-Q.; Weber, W.D.; Chen, J.J.; Kim, E.N.; Kuo, P.-L.; Visconti, P.E.; Takemaru, K.-I. The Cby3/ciBAR1 Complex Positions the Annulus along the Sperm Flagellum during Spermiogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202307147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ren, X.; Chen, X.; Hao, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Transcriptomic Variation during Spermiogenesis in Mouse Germ Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Rong, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Tan, J. Unraveling the Epigenetic Landscape: m6A Modifications in Spermatogenesis and Their Implications for Azoospermia. Discov. Med. 2025, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Kumar, L.; Li, Y.; Baptissart, M. Post-Transcriptional Regulation in Spermatogenesis: All RNA Pathways Lead to Healthy Sperm. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2021, 78, 8049–8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Klukovich, R.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Klungland, A.; Yan, W. ALKBH5-Dependent m6A Demethylation Controls Splicing and Stability of Long 3’-UTR mRNAs in Male Germ Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E325–E333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosronezhad, N.; Hosseinzadeh Colagar, A.; Mortazavi, S.M. The Nsun7 (A11337)-Deletion Mutation, Causes Reduction of Its Protein Rate and Associated with Sperm Motility Defect in Infertile Men. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Tuorto, F.; Menon, S.; Blanco, S.; Cox, C.; Flores, J.V.; Watt, S.; Kudo, N.R.; Lyko, F.; Frye, M. The Mouse Cytosine-5 RNA Methyltransferase NSun2 Is a Component of the Chromatoid Body and Required for Testis Differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Barahona, V.; Soler, M.; Davalos, V.; García-Prieto, C.A.; Janin, M.; Setien, F.; Fernández-Rebollo, I.; Bech-Serra, J.J.; De La Torre, C.; Guil, S.; et al. Epigenetic Inactivation of the 5-Methylcytosine RNA Methyltransferase NSUN7 Is Associated with Clinical Outcome and Therapeutic Vulnerability in Liver Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, E.A.; Averina, O.A.; Isaev, S.V.; Pletnev, P.I.; Bragina, E.E.; Permyakov, O.A.; Buev, V.S.; Priymak, A.V.; Emelianova, M.A.; Pshanichnaya, L.; et al. Positioning of Sperm Tail Longitudinal Columns Depends on NSUN7, an RNA-Binding Protein Destabilizing Elongated Spermatid Transcripts. RNA 2025, 31, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, S.A.; Petrukov, K.S.; Pletnev, F.I.; Sergiev, P.V.; Dontsova, O.A. RNA (C5-Cytosine) Methyltransferases. Biochem. Biokhimiia 2019, 84, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, E.A.; Averina, O.A.; Buev, V.S.; Bragina, E.E.; Permyakov, O.A.; Priymak, A.V.; Emelianova, M.A.; Romanov, E.A.; Grigoryeva, O.O.; Manskikh, V.N.; et al. Testis-Specific RNA Methyltransferase NSUN7 Contains a Re-Arranged Catalytic Site. Biochimie 2025, 236, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, O.; Leduc, F.; Acteau, G.; Arguin, M.; Grégoire, M.-C.; Brazeau, M.-A.; Marois, I.; Richter, M.V.; Boissonneault, G. Step-Specific Sorting of Mouse Spermatids by Flow Cytometry. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2015, 106, e53379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Agustin, J.T.; Pazour, G.J.; Witman, G.B. Intraflagellar Transport Is Essential for Mammalian Spermiogenesis but Is Absent in Mature Sperm. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 4358–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosronezhad, N.; Colagar, A.H.; Jorsarayi, S.G.A. T26248G-Transversion Mutation in Exon7 of the Putative Methyltransferase Nsun7 Gene Causes a Change in Protein Folding Associated with Reduced Sperm Motility in Asthenospermic Men. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2015, 27, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Oliveira, M.E.; Santos, R.; Oliveira, E.; Barbosa, T.; Santos, T.; Gonçalves, P.; Ferraz, L.; Pinto, S.; Barros, A.; et al. Characterization of CCDC103 Expression Profiles: Further Insights in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and in Human Reproduction. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1683–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Shinohara, K.; Botilde, Y.; Nabeshima, R.; Asai, Y.; Fukumoto, A.; Hasegawa, T.; Matsuo, M.; Takeda, H.; Shiratori, H.; et al. Pih1d3 Is Required for Cytoplasmic Preassembly of Axonemal Dynein in Mouse Sperm. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 204, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, G.-D.; Shi, S.-L.; Song, W.-Y.; Jin, H.-X.; Peng, Z.-F.; Yang, H.-Y.; Wang, E.-Y.; Sun, Y.-P. Role of PAFAH1B1 in Human Spermatogenesis, Fertilization and Early Embryonic Development. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 31, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Heck, A.; Zohn, I.E.; Okabe, N.; Pollock, A.; Lenhart, K.B.; Sullivan-Brown, J.; McSheene, J.; Loges, N.T.; Olbrich, H.; Haeffner, K.; et al. The Coiled-Coil Domain Containing Protein CCDC40 Is Essential for Motile Cilia Function and Left-Right Axis Formation. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, M.; Katoh, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Hirano, T.; Sugawa, M.; Tsurumi, Y.; Nakayama, K. Ciliopathy-Associated Mutations of IFT122 Impair Ciliary Protein Trafficking but Not Ciliogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, J.M. Intraflagellar Transport. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003, 19, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Pan, J. Functional Exploration of the IFT-A Complex in Intraflagellar Transport and Ciliogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Plectin: Dual Participation in Tumor Progression. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprando, R.L.; Russell, L.D. Comparative Study of Cytoplasmic Elimination in Spermatids of Selected Mammalian Species. Am. J. Anat. 1987, 178, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristaeus de Asis, M.; Pires, M.; Lyon, K.; Vogl, A.W. A Network of Spectrin and Plectin Surrounds the Actin Cuffs of Apical Tubulobulbar Complexes in the Rat. Spermatogenesis 2013, 3, e25733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytology of the Testis and Intrinsic Control Mechanisms. In Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 827–947.

- Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Xu, C.; Gao, Y.; Lv, M.; Guo, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, P.; et al. DNALI1 Deficiency Causes Male Infertility with Severe Asthenozoospermia in Humans and Mice by Disrupting the Assembly of the Flagellar Inner Dynein Arms and Fibrous Sheath. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, J.A.; Conery, A.R.; Bryant, B.M.; Sandy, P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Mele, D.A.; Bergeron, L.; Sims, R.J. Targeting MYC Dependence in Cancer by Inhibiting BET Bromodomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16669–16674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.Y.; Zhong, R.; Ding, X.P.; Chen, Z.Y.; Jing, Y.L. Investigation of Polymorphisms in Exon7 of the NSUN7 Gene among Chinese Han Men with Asthenospermia. Genet. Mol. Res. GMR 2015, 14, 9261–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cui, S.; Xiong, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Q.; Xia, X.-G.; Zhou, H. PIH1D3-Knockout Rats Exhibit Full Ciliopathy Features and Dysfunctional Pre-Assembly and Loading of Dynein Arms in Motile Cilia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1282787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Ishida, Y.; Hirano, T.; Katoh, Y.; Nakayama, K. Cooperation of the IFT-A Complex with the IFT-B Complex Is Required for Ciliary Retrograde Protein Trafficking and GPCR Import. Mol. Biol. Cell 2021, 32, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, J.L.; Witman, G.B. Intraflagellar Transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalo, F.R.; Reiter, J.F. Open Sesame: How Transition Fibers and the Transition Zone Control Ciliary Composition. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; D’Souza, R.; Sonawane, S.; Gaonkar, R.; Pathak, S.; Jhadav, A.; Balasinor, N.H. Altered Phosphorylation and Distribution Status of Vimentin in Rat Seminiferous Epithelium Following 17β-Estradiol Treatment. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 136, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, W.-Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Hua, M.-M.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Zhou, Y.-J.; Wu, X.-Y.; Li, H.; Liu, M.-F.; et al. NSUN7 Is a Catalytically Inactive RNA m5C Methyltransferase Essential for Sperm Flagellum Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-309-15400-0. [Google Scholar]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.C.; O’Brien, S.J. Genetic Variance of Laboratory Outbred Swiss Mice. Nature 1980, 283, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized p.p.b.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Neuhauser, N.; Michalski, A.; Scheltema, R.A.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. Andromeda: A Peptide Search Engine Integrated into the MaxQuant Environment. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Li, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, W.; Shen, J.; Wu, R.; Ying, W.; Yu, L.; Zi, J.; et al. Prediction and Validation of Mouse Meiosis-Essential Genes Based on Spermatogenesis Proteome Dynamics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2021, 20, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Hein, M.Y.; Luber, C.A.; Paron, I.; Nagaraj, N.; Mann, M. Accurate Proteome-Wide Label-Free Quantification by Delayed Normalization and Maximal Peptide Ratio Extraction, Termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2014, 13, 2513–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Smits, A.H.; van Tilburg, G.B.; Ovaa, H.; Huber, W.; Vermeulen, M. Proteome-Wide Identification of Ubiquitin Interactions Using UbIA-MS. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A Graphical Gene-Set Enrichment Tool for Animals and Plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buev, V.S.; Guseva, E.A.; Rubtsova, M.P.; Priymak, A.V.; Novikova, S.E.; Averina, O.A.; Permyakov, O.A.; Grigoryeva, O.O.; Manskikh, V.N.; Zgoda, V.G.; et al. NSUN7 Regulates Sperm Flagella Formation at All Stages of Spermiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010257

Buev VS, Guseva EA, Rubtsova MP, Priymak AV, Novikova SE, Averina OA, Permyakov OA, Grigoryeva OO, Manskikh VN, Zgoda VG, et al. NSUN7 Regulates Sperm Flagella Formation at All Stages of Spermiogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010257

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuev, Vitaly S., Ekaterina A. Guseva, Maria P. Rubtsova, Anastasia V. Priymak, Svetlana E. Novikova, Olga A. Averina, Oleg A. Permyakov, Olga O. Grigoryeva, Vasily N. Manskikh, Victor G. Zgoda, and et al. 2026. "NSUN7 Regulates Sperm Flagella Formation at All Stages of Spermiogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010257

APA StyleBuev, V. S., Guseva, E. A., Rubtsova, M. P., Priymak, A. V., Novikova, S. E., Averina, O. A., Permyakov, O. A., Grigoryeva, O. O., Manskikh, V. N., Zgoda, V. G., Dontsova, O. A., & Sergiev, P. V. (2026). NSUN7 Regulates Sperm Flagella Formation at All Stages of Spermiogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010257