Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Cardiac Regeneration: Opportunity for Cell-Free Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Burden, Risk Factors, and Limitations of Current Treatments

1.2. Cardiac Progenitor Cells (CPCs) and Cardiac-Derived Stromal Cells (CSCs)

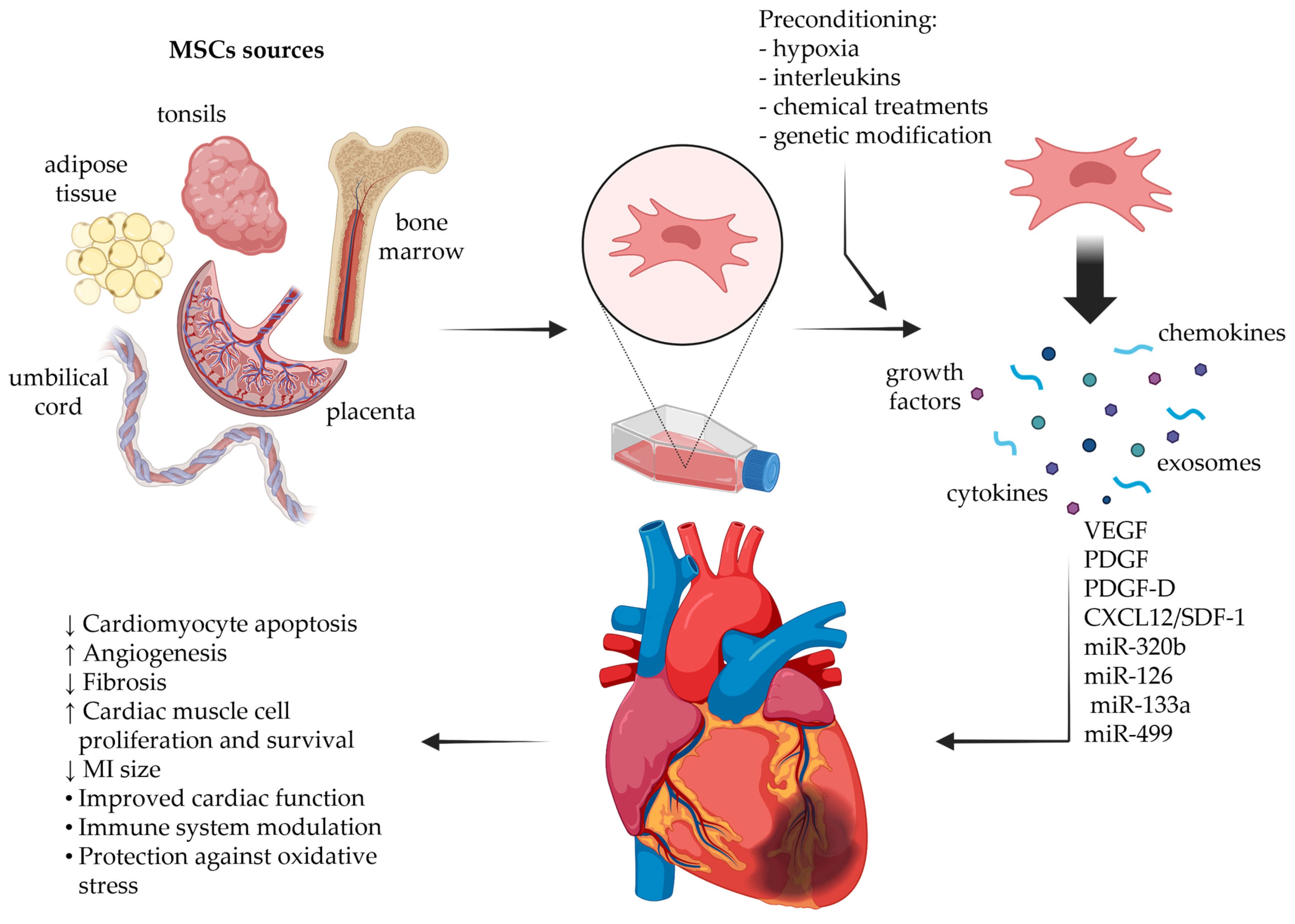

1.3. Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cardiac Regeneration

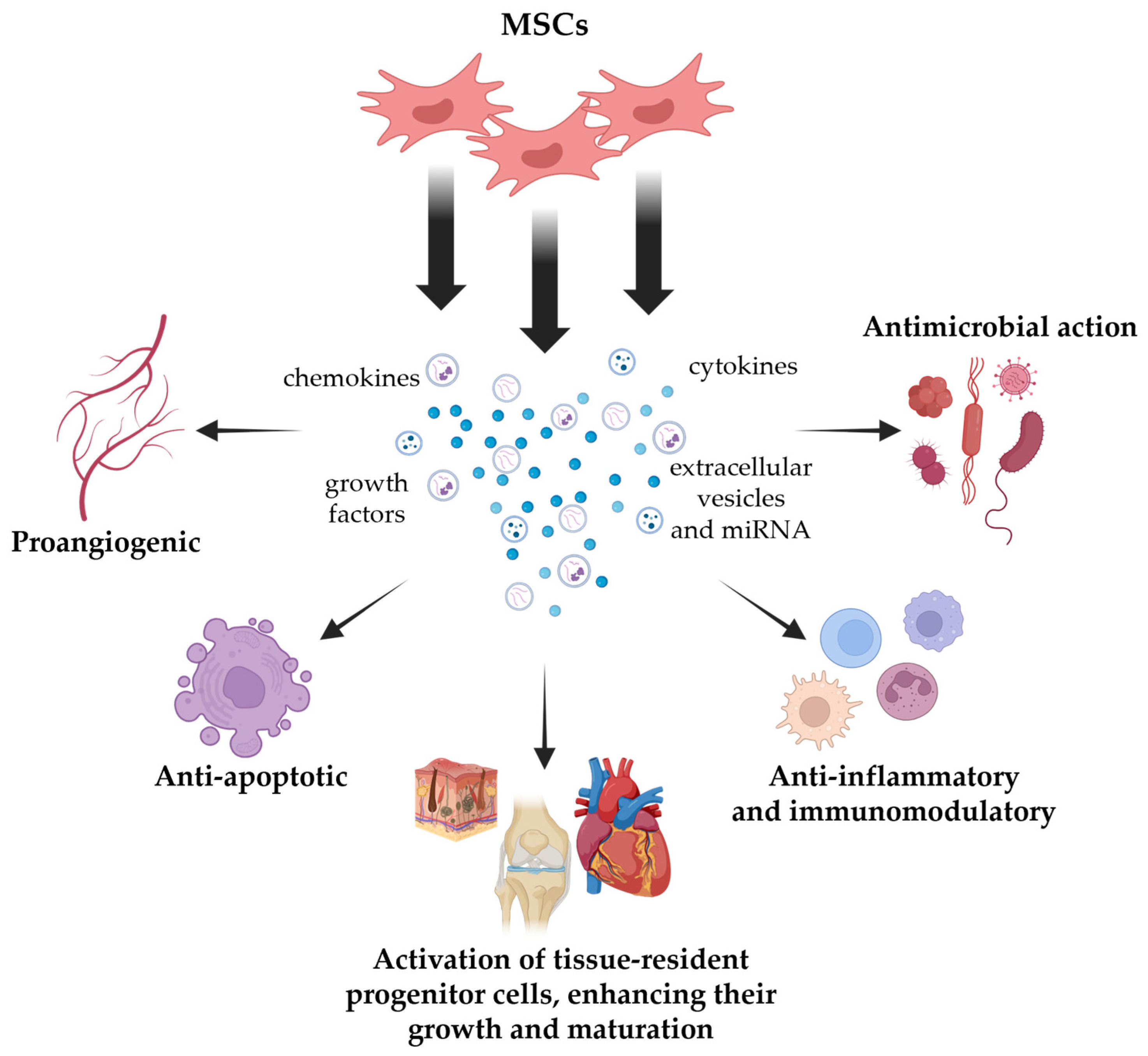

2. MSC Secretome

2.1. MSC Secretome Composition

2.2. Priming Approaches to Tailor MSC Secretome Composition

2.3. Methods of Preparation of MSC Secretomes

| Parameter | Cell Type | Passage/ Confluence | Base Medium | CM Induction Medium | Induction Time | Pre- Treatment | Concentration Method | Concentration Factor | Cut-Off (kDa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. | ||||||||||

| [60] | Tonsil-derived MSCs | P7–9, 80% | Low-glucose DMEM | Low- glucose DMEM (serum-free implied) | 48 h | None specified | Amicon Ultra (centrifugal) | 20-fold | Not specified | |

| [68] | hMSCs (ATCC) | Confluence | α- MEM | Serum-free | 48 h | None specified | Amicon Ultra-15 (centrifugal) | Not specified | 100 kDa | |

| [69] | MSCs | 90% | DMEM | Serum-free | 12 h | 20 ng/mL IFN-γ TNF-α | Ultrafiltration (membrane) | Not specified | 3 kDa | |

| [70] | WJ-MSCs | P4, 80% | DMEM | hPL-free DMEM | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | None specified | Ultrafiltration | Not specified | Not specified | |

| [64] | UC-MSCs | 80–90% | L-DMEM | Serum-free | 48 h | Akt Transfection | Ultrafiltration (membrane) | Not specified | 100 kDa | |

3. Advantages and Challenges of MSC-Derived Cell-Free Therapy

4. Recent Preclinical Findings in Cardiac Regeneration

| Cells/Animal | Form (Dose) | Types of MSCs | Secretome/ Exosomes | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyocytes isolated from rat hearts | 30 ug/mL | MSC (human ATCC) | Exosomes | Improvement of cell viability and reduction in apoptosis; pyroptosis inhibition | [82] |

| Mouse and H9c2 cells | 50 μL of CM (4 μg/mL | AT-MSC (human) | Secretome | Decreased apoptosis and fibrosis | [79] |

| Rat | 400 μg | UC-MSC (human) | Secretome | Improved cardiac function, decreased apoptosis, increased angiogenesis | [78] |

| Rat | 20 μg/20 μL | UC-MSC (human) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, reduced MI size, decreased inflammation | [64] |

| Rat | 600 μL | BM-MSC (rat) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, reduced MI size | [61] |

| Mouse | 20 μg/mL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Secretome | Improved cardiac function, decreased apoptosis, increased angiogenesis | [83] |

| Mouse | 50 μg/30 μL | Cardiac- MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, increased angiogenesis | [62] |

| Mouse | 0.5 μg/μL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Decreased apoptosis | [84] |

| Mouse | 50 μg/100 μL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, increased angiogenesis, decreased MI size, decreased inflammation | [85] |

| Mouse | 600 μg/20 μL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, increased angiogenesis | [86] |

| Mouse | 5 μg/25 μL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, decreased apoptosis | [87] |

| Rat | 40 μg/300 μL | MSC (human ATCC) | Exosomes | Decreased MI size, apoptosis, and inflammation | [88] |

| Rat | 50 μg/mL | UC- MSC (human Shycbio) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, decreased MI size and apoptosis, increased angiogenesis | [65] |

| Rat | 80 μg/200 μL | BM-MSC (rat) | Extracellular vesicles | Improved cardiac function, decreased MI size, decreased inflammation | [81] |

| Rat | 500 μL | BM-MSC (human) | Secretome | Decreased MI size, increased angiogenesis | [63] |

| Mouse | 50 μg/25 μL | BM-MSC (mouse) | Exosomes | Decreased MI size and inflammation | [89] |

| Mouse | 20 μg/30 μL | MSC (not specified) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, decreased MI size, increased angiogenesis | [90] |

| Mouse | 10 μg/100 μL | BM-MSC (rat) | Extracellular vesicles | Improved cardiac function, decreased collagen volume | [91] |

| Pig | 1000 μg | Embryo MSC (human cell line) | Exosomes | Reduced infarct size and protected regional cardiac wall function | [80] |

| Mouse, Rat, Pig | 9 × 1010 particles/mL | MSC (not specified) | Exosomes | Improved cardiac function, decreased MI size | [92] |

5. Conclusions and Further Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Arachidonoyl acid |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| Akt- Exo | Akt-modified human umbilical cord-derived MSCs |

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| Ang-1 | Angiopoietin 1 |

| ATMSCs | Adipose tissue-derived MSCs |

| BM-MSCs | Bone marrow-derived MSCs |

| CASCs | Cardiac atrial appendage stromal cells |

| CADSCs | Cardiac adipose-derived stromal cells |

| CDC | Cardiosphere-derived cells |

| CM | Conditioned medium |

| CPCs | Cardiac progenitor cells |

| CSCs | Cardiac-derived stromal cells |

| cSPCs | Cardiac side population cells |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DFO | Deferoxamine |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| DMEM | Dulbeco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoyl acid |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast growth factor 2 |

| GMP | Good manufacture practice |

| GRO | Growth-regulated protein |

| HATMSCs | Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| HMSCs | Human-derived MSCs |

| hPL | Human platelet lysate |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IP-10 | Interferon-gamma-induced protein 10 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MCP1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| MMP3 | Matrix metalloproteinase-3 |

| mRNAs | Messenger RNAs |

| MSC-CM | MSC-derived conditioned medium |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal/stromal stem cells |

| MVs | Microvesicles |

| PEA | N-palmitoylethanolamide |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin-E2 |

| PGF2α | Prostaglandin-F2α |

| Sca-1+ | Stem cell antigen-1 |

| SEA | N-stearoylethanolamide |

| sEVs-Ge | sEVs incorporated into an alginate hydrogel |

| SPCs | Side population cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor β |

| TIMP1 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor α |

| UC- MSCs | Umbilical cord MSCs |

| uPAR | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WJ-MSCs | Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs |

| αMEM | Modified minimum essential medium |

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks: A Compass for Global Action. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2980–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.; Mills, N.L. A new clinical classification of acute myocardial infarction. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2200–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafei, A.E.; Ali, M.A.; Ghanem, H.G.; Shehata, A.I.; Abdelgawad, A.A.; Handal, H.R.; Talaat, K.A.; Ashaal, A.E.; El-Shal, A.S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: A promising cell-based therapy for treatment of myocardial infarction. J. Gene Med. 2017, 19, e2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; White, H.D.; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction; Jaffe, A.S.; Apple, F.S.; Galvani, M.; Katus, H.A.; Newby, L.K.; Ravkilde, J.; et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2007, 116, 2634–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Simoons, M.L.; Chaitman, B.R.; White, H.D.; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction; Katus, H.A.; Lindahl, B.; Morrow, D.A.; et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012, 126, 2020–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Ambrose, J.A. Understanding myocardial infarction. F1000Res 2018, 7, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbasiafshar, C.; Sellke, F.W.; Abid, M.R. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the failing heart: Past, present, and future. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1999–H2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, S.; Sanborn, T. Acute myocardial infarction. Dis. Mon. 2013, 59, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E.; Bristow, M.R. Congestive heart failure: Fifty years of progress. Circulation 2000, 102, IV14-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, K.R. Stress pathways and heart failure. Cell 1999, 98, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.J.; Chien, K.R. Signaling pathways for cardiac hypertrophy and failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, F.B. Cardiomyocyte proliferation: A platform for mammalian cardiac repair. Cell Cycle 2005, 4, 1360–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimczak, A.; Kozlowska, U. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Tissue-Specific Progenitor Cells: Their Role in Tissue Homeostasis. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4285215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, K.; White, G.; Khan, S.; Luba, J.; Benharash, P.; Thankam, F.G. Heart-derived endogenous stem cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollini, S.; Smart, N.; Riley, P.R. Resident cardiac progenitor cells: At the heart of regeneration. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2011, 50, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; McKee, C.; Bakshi, S.; Walker, K.; Hakman, E.; Halassy, S.; Svinarich, D.; Dodds, R.; Govind, C.K.; Chaudhry, G.R. Mesenchymal stem cells: Cell therapy and regeneration potential. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1738–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczenko, A.; Klimczak, A. Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Their Contribution to Angiogenic Processes in Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT(R)) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Linthout, S.; Stamm, C.; Schultheiss, H.P.; Tschope, C. Mesenchymal stem cells and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: Cardiac homing and beyond. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 757154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.N.; Bolli, R.; Hare, J.M. Clinical Studies of Cell Therapy in Cardiovascular Medicine: Recent Developments and Future Directions. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 266–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Falguera, D.; Iborra-Egea, O.; Galvez-Monton, C. iPSC Therapy for Myocardial Infarction in Large Animal Models: Land of Hope and Dreams. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csobonyeiova, M.; Beerova, N.; Klein, M.; Debreova-Cehakova, M.; Danisovic, L. Cell-Based and Selected Cell-Free Therapies for Myocardial Infarction: How Do They Compare to the Current Treatment Options? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuh, E.; Brinton, T.J. Bone marrow stem cells for the treatment of ischemic heart disease: A clinical trial review. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2009, 2, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, C.; Jia, L.; Du, J. Heart regeneration, stem cells, and cytokines. Regen. Med. Res. 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirotsou, M.; Zhang, Z.; Deb, A.; Zhang, L.; Gnecchi, M.; Noiseux, N.; Mu, H.; Pachori, A.; Dzau, V. Secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) is the key Akt-mesenchymal stem cell-released paracrine factor mediating myocardial survival and repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laflamme, M.A.; Murry, C.E. Heart regeneration. Nature 2011, 473, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Shen, Y.; Ren, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Asahara, T.; Yang, J. Inflammation in myocardial infarction: Roles of mesenchymal stem cells and their secretome. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Ma, S.; Dong, M.; Wang, J.; Chai, S.; Liu, T.; Li, J. Effect of interleukin-6 on myocardial regeneration in mice after cardiac injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkenov, N.; Mukhatayev, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kushugulova, A. Systematic Review on the Role of IL-6 and IL-1beta in Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarbanell, A.M.; Coffey, A.C.; Fehrenbacher, J.W.; Beckman, D.J.; Herrmann, J.L.; Weil, B.; Meldrum, D.R. Proinflammatory cytokine effects on mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the ischemic heart. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 88, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, M.; Simons, M. Fibroblast growth factor regulation of neovascularization. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2008, 15, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonna, R.; Angelucci, S.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Doria, V.; Giricz, Z.; Gorbe, A.; Ferdinandy, P.; De Caterina, R. Proteomic analysis of the secretome of adipose tissue-derived murine mesenchymal cells overexpressing telomerase and myocardin. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2019, 131, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraskiewicz, H.; Paprocka, M.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Krawczenko, A.; Panek, K.; Kaczynska, J.; Szyposzynska, A.; Psurski, M.; Kuropka, P.; Klimczak, A. Can supernatant from immortalized adipose tissue MSC replace cell therapy? An in vitro study in chronic wounds model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Bioactive Lipids as Mediators of the Beneficial Action(s) of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in COVID-19. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, S.; Giannasi, C.; Niada, S.; Della Morte, E.; Orioli, M.; Brini, A.T. Lipidomics of Cell Secretome Combined with the Study of Selected Bioactive Lipids in an In Vitro Model of Osteoarthritis. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, S.; Giannasi, C.; Niada, S.; Bergamaschi, R.F.; Orioli, M.; Brini, A.T. Bioactive Lipids in MSCs Biology: State of the Art and Role in Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecchi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, A.; Dzau, V.J. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 1204–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraskiewicz, H.; Hinc, P.; Krawczenko, A.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Paprocka, M.; Witkowska, D.; Mohd Isa, I.L.; Pandit, A.; Klimczak, A. HATMSC Secreted Factors in the Hydrogel as a Potential Treatment for Chronic Wounds-In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Lee, J.; Kwon, Y.; Park, K.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, S.J.; Bang, S.I.; Chang, J.W.; Lee, C. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of the Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secretome from Adipose, Bone Marrow, Placenta and Wharton’s Jelly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szyposzynska, A.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Krawczenko, A.; Doszyn, O.; Paprocka, M.; Klimczak, A. Suppression of Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth by AT-MSC Microvesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczenko, A.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Paprocka, M.; Kraskiewicz, H.; Szyposzynska, A.; Wojdat, E.; Klimczak, A. Microvesicles from Human Immortalized Cell Lines of Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells of Adipose Tissue Origin as Carriers of Bioactive Factors Facilitating Angiogenesis. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 1289380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyposzynska, A.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Murawski, M.; Sozanski, R.; Chodaczek, G.; Klimczak, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Microvesicles from Adipose Tissue: Unraveling Their Impact on Primary Ovarian Cancer Cells and Their Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, N.; Sun, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Masoudi, A.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; et al. Proteomic characterization of hUC-MSC extracellular vesicles and evaluation of its therapeutic potential to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, C.; Zhao, R.; Lu, H.; Song, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, B.; Ge, J. Hypoxia-induced signaling in the cardiovascular system: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.S.; Shao, K.; Liu, C.W.; Li, C.J.; Yu, B.T. Hypoxic preconditioning BMSCs-exosomes inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis after acute myocardial infarction by upregulating microRNA-24. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 6691–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Chao, J.; Yang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z. Hypoxia-Elicited Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Alleviate Myocardial Infarction by Promoting Angiogenesis through the miR-214/Sufu Pathway. Stem Cells Int. 2023, 2023, 1662182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.M.; Verma, S.; Upadhya, R.; Bhat, S.; Seetharam, R.N. Inflammatory priming of mesenchymal stromal cells enhances its secretome potential through secretion of anti-inflammatory and ECM modulating factors: Insights into proteomic and functional properties. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 778, 152391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yoo, S.M.; Park, H.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.L.; Seo, K.W.; Kang, K.S. Preconditioning with interleukin-1 beta and interferon-gamma enhances the efficacy of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells-based therapy via enhancing prostaglandin E2 secretion and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1792–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Castro, E.; Cunningham, C.; Miller, J.; Martuscelli, L.; Aoulad-Ali, S.; Rothwell, N.J.; Kielty, C.M.; Allan, S.M.; Pinteaux, E. Interleukin-1 primes human mesenchymal stem cells towards an anti-inflammatory and pro-trophic phenotype in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Ma, Y.; Iyer, R.P.; DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Garrett, M.R.; Lindsey, M.L. IL-10 improves cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by stimulating M2 macrophage polarization and fibroblast activation. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, F.; Chai, R.; Zhou, W.; Hu, M.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, Q.; Liu, N.; et al. Exosomes derived from pro-inflammatory bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammation and myocardial injury via mediating macrophage polarization. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7617–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, A.; Nader, V.; Lebrin, M.; Gross, F.; Prats, A.C.; Cussac, D.; Galinier, M.; Roncalli, J. Pre-Conditioning Methods and Novel Approaches with Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Tian, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, G.; Qian, H.; Jin, C.; et al. Atorvastatin enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes in acute myocardial infarction via up-regulating long non-coding RNA H19. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Huang, P.; Chen, G.; Xiong, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Tang, R.; et al. Atorvastatin-pretreated mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote cardiac repair after myocardial infarction via shifting macrophage polarization by targeting microRNA-139-3p/Stat1 pathway. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z.; Chi, B.; Zou, A.; Mao, L.; Xiong, X.; Jiang, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, W.; et al. HIF-1alpha overexpression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome-encapsulated arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) hydrogels boost therapeutic efficacy of cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Mater. Today Bio 2021, 12, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Ma, R.; Cai, W.; Huang, W.; Paul, C.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Kim, H.W.; Xu, M.; et al. Exosomes Secreted from CXCR4 Overexpressing Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Cardioprotection via Akt Signaling Pathway following Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 659890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprocka, M.; Kraskiewicz, H.; Bielawska-Pohl, A.; Krawczenko, A.; Maslowski, L.; Czyzewska-Buczynska, A.; Witkiewicz, W.; Dus, D.; Czarnecka, A. From Primary MSC Culture of Adipose Tissue to Immortalized Cell Line Producing Cytokines for Potential Use in Regenerative Medicine Therapy or Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, K.A.; Woo, S.Y.; Ryu, K.H. Conditioned medium from human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibits glucocorticoid-induced adipocyte differentiation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, P.; Meng, Q.; Geng, Y.J.; Yu, X.Y.; et al. MiRNA-Sequence Indicates That Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes Have Similar Mechanism to Enhance Cardiac Repair. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4150705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.G.; Li, H.R.; Han, J.X.; Li, B.B.; Yan, D.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, P.; Luo, Y. GATA-4-expressing mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction via secreted exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9047, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefai, M.T.; Tarola, C.L.; Raagas, R.; Ridwan, K.; Shalal, M.; Lomis, N.; Paul, A.; Alrefai, M.D.; Prakash, S.; Schwertani, A.; et al. Functional Assessment of Pluripotent and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Secretome in Heart Disease. Ann. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L.; Sun, X.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X.; Qian, H.; Xu, W.; Zhu, W. Exosomes Derived from Akt-Modified Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Cardiac Regeneration and Promote Angiogenesis via Activating Platelet-Derived Growth Factor D. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Liu, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y.W.; Liu, Z. Exosomes Derived from TIMP2-Modified Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhance the Repair Effect in Rat Model with Myocardial Infarction Possibly by the Akt/Sfrp2 Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 1958941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.J.; Bae, Y.K.; Kim, M.; Kwon, S.J.; Jeon, H.B.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, S.W.; Yang, Y.S.; Oh, W.; Chang, J.W. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood as sources of cell therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 17986–18001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, Y.A.; Volgina, N.E.; Vtorushina, V.V.; Romanov, A.Y.; Dugina, T.N.; Kabaeva, N.V.; Sukhikh, G.T. Comparative Analysis of Secretome of Human Umbilical Cord- and Bone Marrow-Derived Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 166, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.; Ravindran, S.; Liu, X.; Torres, L.; Chennakesavalu, M.; Huang, C.C.; Feng, L.; Zelka, R.; Lopez, J.; Sharma, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles and retinal ischemia-reperfusion. Biomaterials 2019, 197, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, F.; Lu, Y.; Du, P.; Hu, K.; Yin, X.; Zhao, P.; Lu, G. The conditioned medium from mesenchymal stromal cells pretreated with proinflammatory cytokines promote fibroblasts migration and activation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acuto, S.; Lo Iacono, M.; Baiamonte, E.; Lo Re, R.; Maggio, A.; Cavalieri, V. An optimized procedure for preparation of conditioned medium from Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stromal cells isolated from umbilical cord. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1273814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, S.H.; Levy, O.; Inamdar, M.S.; Karp, J.M. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, F.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Innovative approaches to boost mesenchymal stem cells efficacy in myocardial infarction therapy. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid-Otmane, C.; Perrault, L.P.; Ly, H.Q. Mesenchymal stem cell mediates cardiac repair through autocrine, paracrine and endocrine axes. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijani-Ghazyani, Z.; Roushandeh, A.M.; Sabzevari, R.; Salari, A.; Razavi Toosi, M.T.; Jahanian-Najafabadi, A.; Roudkenar, M.H. Conditioned medium harvested from Hif1alpha engineered mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates LAD-occlusion -induced injury in rat acute myocardial ischemia model. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 130, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, X.; Pu, J.; Hu, H. Cardiac cells and mesenchymal stem cells derived extracellular vesicles: A potential therapeutic strategy for myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1493290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.M.; Sabe, S.A.; Brinck-Teixeira, R.; Sabra, M.; Sellke, F.W.; Abid, M.R. Visualization of cardiac uptake of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles after intramyocardial or intravenous injection in murine myocardial infarction. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, N.; Mester-Tonczar, J.; Winkler, J.; Traxler, D.; Spannbauer, A.; Ruger, B.M.; Goliasch, G.; Pavo, N.; Gyongyosi, M.; Zlabinger, K. Comparative Effect of MSC Secretome to MSC Co-culture on Cardiomyocyte Gene Expression Under Hypoxic Conditions in vitro. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 502213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoulvant, D.; Ivanes, F.; Ferrera, R.; Matthews, P.G.; Nataf, S.; Ovize, M. Mesenchymal stem cell conditioned media attenuates in vitro and ex vivo myocardial reperfusion injury. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2011, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.L.; Lai, T.C.; Lin, S.R.; Lin, S.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Pu, C.M.; Lee, I.T.; Tsai, J.S.; Lee, C.W.; Chen, Y.L. Conditioned medium from adipose-derived stem cells attenuates ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiac injury through the microRNA-221/222/PUMA/ETS-1 pathway. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3131–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, C.J.; Li, R.R.; Yeung, T.; Mazlan, S.M.I.; Lai, R.C.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; Lim, S.K.; Richards, A.M. Systemic Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce Myocardial Infarct Size: Characterization With MRI in a Porcine Model. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 601990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, C.; et al. Incorporation of small extracellular vesicles in sodium alginate hydrogel as a novel therapeutic strategy for myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 7403–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Lu, L.; Ma, J.; Ding, P.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect the Myocardium Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Through Inhibiting Pyroptosis. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2020, 14, 3765–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Patnaik, S.; Duan, Z.H.; Kiedrowski, M.; Penn, M.S.; Mayorga, M.E. A Novel Role for CAMKK1 in the Regulation of the Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Liu, N.; Ma, G.; Tang, Y. Transplantation of Cardiac Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Angiogenesis. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018, 11, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, K.M.; Haar, L.; McGuinness, M.; Wang, Y.; Lynch Iv, T.L.; Phan, A.; Song, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gardner, G.; Kuffel, G.; et al. Exosomal miR-21a-5p mediates cardioprotection by mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2018, 119, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Meng, Q.; Yu, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; et al. Engineered Exosomes With Ischemic Myocardium-Targeting Peptide for Targeted Therapy in Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Sun, J.; Shao, L.; Yu, Y.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-132, Delivered by Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes, Promote Angiogenesis in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 3290372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Liang, X.L.; Zhang, C.L.; Pang, Y.H.; Lu, Y.X. LncRNA KLF3-AS1 in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorates pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction through miR-138-5p/Sirt1 axis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, F.; Qiao, S.; Sun, X.; Gao, L.; Xie, J.; Xu, B. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury through miR-182-regulated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liang, X.; Han, Q.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Hong, Y.; Li, W.; Mai, C.; Mo, Q.; et al. Hemin enhances the cardioprotective effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes against infarction via amelioration of cardiomyocyte senescence. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Song, Y.; Huang, Z.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; Yang, H.; Fan, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; et al. Monocyte mimics improve mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle homing in a mouse MI/RI model. Biomaterials 2020, 255, 120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Huang, K.; Zhu, D.; Chen, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mi, L.; Xuan, H.; Hu, S.; Li, J.; et al. A Minimally Invasive Exosome Spray Repairs Heart after Myocardial Infarction. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 11099–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piotrowska, P.; Kraskiewicz, H.; Klimczak, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Cardiac Regeneration: Opportunity for Cell-Free Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010209

Piotrowska P, Kraskiewicz H, Klimczak A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Cardiac Regeneration: Opportunity for Cell-Free Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010209

Chicago/Turabian StylePiotrowska, Paulina, Honorata Kraskiewicz, and Aleksandra Klimczak. 2026. "Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Cardiac Regeneration: Opportunity for Cell-Free Therapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010209

APA StylePiotrowska, P., Kraskiewicz, H., & Klimczak, A. (2026). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Cardiac Regeneration: Opportunity for Cell-Free Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010209