Hepatic FGF21 Deletion Improves Glucose Metabolism, Alters Lipogenic and Chrna4 Gene Expression, and Enhances Telomere Maintenance in Aged Female Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Lifelong Hepatic FGF21 Deficiency Reduces Body Weight and Improves Glucose Tolerance in Females

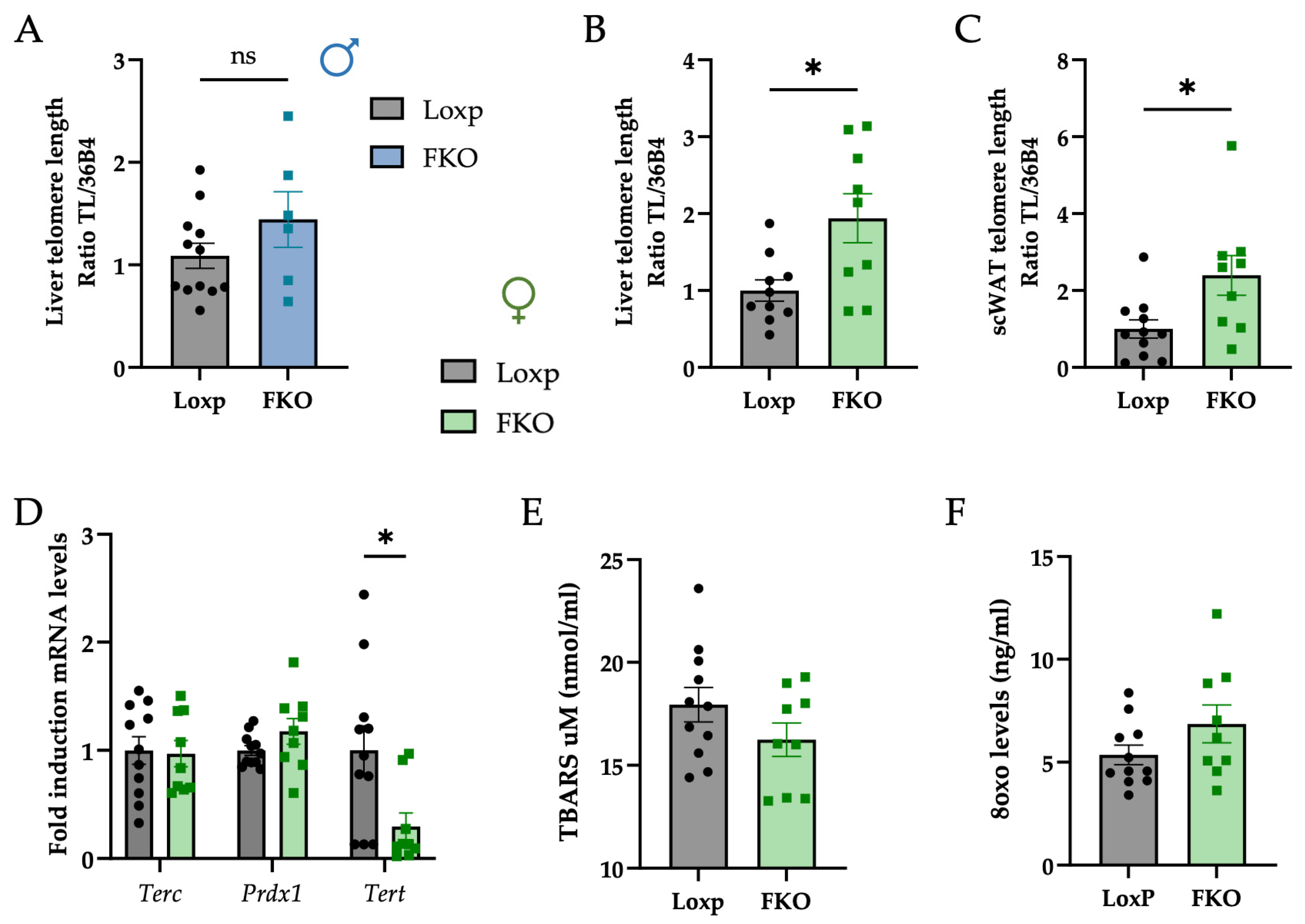

2.2. FKO Females Exhibit Longer Telomeres in Hepatocytes and Adipocytes

2.3. Hepatic FGF21deficiency Suppresses Lipogenic Genes and Enhances Fatty Acid Uptake and b-Oxidation Markers in the Liver

2.4. Hepatic FGF21 Deficiency Downregulates Genes Related to Cytoskeletal Organization and Immune System in the Liver, Potentially Mediated by ChRNA4

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice Procedures

4.1.1. Mice Housing

4.1.2. Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT)

4.1.3. Tissue and Serum Collection

4.2. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Assay

4.3. ELISA Assays

4.3.1. DNA Damage Competitive ELISA

4.3.2. Mouse Estrogen Competitive ELISA

4.3.3. Mouse Insulin and Fgf21 Sandwich ELISA

4.4. Serum Cholesterol and Hepatic Triglycerides

4.5. RNA Isolation and Retro-Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.6. RNA-Seq Analysis

4.7. Telomere Length (TL) Assessment

4.8. Mitochondrial Biogenesis

4.9. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flippo, K.H.; Potthoff, M.J. Metabolic Messengers: FGF21. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolegowska, K.; Marchelek-Mysliwiec, M.; Nowosiad-Magda, M.; Slawinski, M.; Dolegowska, B. FGF19 Subfamily Members: FGF19 and FGF21. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 75, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Boney-Montoya, J.; Owen, B.M.; Bookout, A.L.; Coate, K.C.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Kliewer, S.A. ΒKslotho Is Required for Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Effects on Growth and Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martí, A.; Sandoval, V.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D.; Relat, J. Nutritional Regulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21: From Macronutrients to Bioactive Dietary Compounds. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2017, 30, 20160034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garza, Ú.; Torres-Oteros, D.; Yarritu-Gallego, A.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D.; Relat, J. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 and the Adaptive Response to Nutritional Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Chui, P.C.; Antonellis, P.J.; Bina, H.A.; Kharitonenkov, A.; Flier, J.S.; Maratos-Flier, E. Obesity Is a Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21)-Resistant State. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2781–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markan, K.R. Defining “FGF21 Resistance” during Obesity: Controversy, Criteria and Unresolved Questions. F1000Res 2018, 7, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanajak, P. Letter to the Editor: Parameters, Characteristics, and Criteria for Defining the Term “FGF21 Resistance”. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 1523–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Regulation of Longevity by FGF21: Interaction between Energy Metabolism and Stress Responses. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzu, V.; Valencak, T.G. Energy Metabolism and Ageing in the Mouse: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2017, 63, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, E.H. Structure and Function of Telomeres. Nature 1991, 350, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shammas, M.A. Telomeres, Lifestyle, Cancer, and Aging. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, D.; LaBella, K.A.; DePinho, R.A. Telomeres: History, Health, and Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2021, 184, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavia-García, G.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Telomere Length and Oxidative Stress and Its Relation with Metabolic Syndrome Components in the Aging. Biology 2021, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, B.T.; Morais, J.A.; Santosa, S. Obesity and Ageing: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, K.R.; Redden, D.T.; Wang, C.; Westfall, A.O.; Allison, D.B. Years of Life Lost Due to Obesity. JAMA 2003, 289, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Nie, Y.; Cao, J.; Luo, M.; Yan, M.; Chen, Z.; He, B. The Roles and Pharmacological Effects of FGF21 in Preventing Aging-Associated Metabolic Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 655575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.J.; Gutiérrez, O.M.; Bamman, M.M.; Ashraf, A.; McCormick, K.L.; Casazza, K. Circulating Levels of Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 Increase with Age Independently of Body Composition Indices among Healthy Individuals. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2015, 2, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya, J.; Gallego-Escuredo, J.M.; Delgado-Anglés, A.; Cairó, M.; Moure, R.; Gracia Mateo, M.; Domingo, J.C.; Domingo, P.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. Aging Is Associated with Increased FGF21 Levels but Unaltered FGF21 Responsiveness in Adipose Tissue. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Uta, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Sato, T.; Okita, N.; Higami, Y. Impact of Aging and Caloric Restriction on Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Signaling in Rat White Adipose Tissue. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 118, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Arnold, W.D.; Huang, W.; Ray, A.; Owendoff, G.; Cao, L. Long-Term Effects of a Fat-Directed FGF21 Gene Therapy in Aged Female Mice. Gene Ther. 2024, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.; Lin, V.Y.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Kliewer, S.A. Inhibition of Growth Hormone Signaling by the Fasting-Induced Hormone FGF21. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Berglund, E.D.; Colbert Coate, K.; He, T.T.; Katafuchi, T.; Xiao, G.; Potthoff, M.J.; Wei, W.; Wan, Y.; et al. The Starvation Hormone, Fibroblast Growth Factor-21, Extends Lifespan in Mice. eLife 2012, 1, e00065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.J.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Fang, E.; Aon, M.; González-Reyes, J.A.; Cortassa, S.; Kaushik, S.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Patel, B.; et al. Effects of Sex, Strain, and Energy Intake on Hallmarks of Aging in Mice. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1093–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.R.; Russo, K.A.; Fang, Y.; Mohajerani, N.; Goodson, M.L.; Ryan, K.K. Sex Differences in the Hormonal and Metabolic Response to Dietary Protein Dilution. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 3477–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.L.; Pak, H.H.; Richardson, N.E.; Flores, V.; Yu, D.; Tomasiewicz, J.L.; Dumas, S.N.; Kredell, K.; Fan, J.W.; Kirsh, C.; et al. Sex and Genetic Background Define the Metabolic, Physiologic, and Molecular Response to Protein Restriction. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 209–226.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhan, N.; Jakovleva, T.; Feofanova, N.; Denisova, E.; Dubinina, A.; Sitnikova, N.; Makarova, E. Sex Differences in Liver, Adipose Tissue, and Muscle Transcriptional Response to Fasting and Refeeding in Mice. Cells 2019, 8, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, E.; Kazantseva, A.; Dubinina, A.; Denisova, E.; Jakovleva, T.; Balybina, N.; Bgatova, N.; Baranov, K.; Bazhan, N. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (Fgf21) Administration Sex-Specifically Affects Blood Insulin Levels and Liver Steatosis in Obese Ay Mice. Cells 2021, 10, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, E.; Kazantseva, A.; Dubinina, A.; Jakovleva, T.; Balybina, N.; Baranov, K.; Bazhan, N. The Same Metabolic Response to FGF21 Administration in Male and Female Obese Mice Is Accompanied by Sex-Specific Changes in Adipose Tissue Gene Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Giesy, S.L.; Hassan, M.; Davis, K.; Zhao, S.; Boisclair, Y.R. Hepatic FGF21 Production Is Increased in Late Pregnancy in the Mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R290–R298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buell-Acosta, J.D.; Garces, M.F.; Parada-Baños, A.J.; Angel-Muller, E.; Paez, M.C.; Eslava-Schmalbach, J.; Escobar-Cordoba, F.; Caminos-Cepeda, S.A.; Lacunza, E.; Castaño, J.P.; et al. Maternal Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Levels Decrease during Early Pregnancy in Normotensive Pregnant Women but Are Higher in Preeclamptic Women—A Longitudinal Study. Cells 2022, 11, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gong, Y.; Wei, X.; Yao, Z.; Yang, R.; Xin, J.; Gao, L.; Shao, S. Changes in Hepatic Triglyceride Content with the Activation of ER Stress and Increased FGF21 Secretion during Pregnancy. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, E.; Gietka-Czernel, M. FGF21: A Novel Regulator of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Whole-Body Energy Balance. Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamberi, T.; Magherini, F.; Modesti, A.; Fiaschi, T. Adiponectin Signaling Pathways in Liver Diseases. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, M.D.L.; Gao, J.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Gromada, J. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Regulates Energy Metabolism by Activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12553–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkız, H.; Gieseler, R.K.; Canbay, A. Liver Fibrosis: From Basic Science towards Clinical Progress, Focusing on the Central Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Koyama, Y.; Wang, P.; Lan, T.; Kim, I.-G.; Kim, I.H.; Ma, H.-Y.; Kisseleva, T. The Types of Hepatic Myofibroblasts Contributing to Liver Fibrosis of Different Etiologies. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Félix, J.M.; González-Núñez, M.; López-Novoa, J.M. ALK1-Smad1/5 Signaling Pathway in Fibrosis Development: Friend or Foe? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Gong, X.; Albanis, E.; Friedman, S.L.; Mao, Z. Regulation of Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Growth by Transcription Factor Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Tian, G.-Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-D.; Shi, J.-P.; Yang, J. Characterization of Transcriptional Modules Related to Fibrosing-NAFLD Progression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, J.; Niu, M.; Hou, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J. MyD88 in Hepatic Stellate Cells Enhances Liver Fibrosis via Promoting Macrophage M1 Polarization. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Yang, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, C.; Qian, M.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Yang, S.; Zheng, M.-H.; et al. Hepatocyte CHRNA4 Mediates the MASH-Promotive Effects of Immune Cell-Produced Acetylcholine and Smoking Exposure in Mice and Humans. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 2231–2249.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Integrated Stress Response Stimulates FGF21 Expression: Systemic Enhancer of Longevity. Cell Signal 2017, 40, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laeger, T.; Henagan, T.M.; Albarado, D.C.; Redman, L.M.; Bray, G.A.; Noland, R.C.; Münzberg, H.; Hutson, S.M.; Gettys, T.W.; Schwartz, M.W.; et al. FGF21 Is an Endocrine Signal of Protein Restriction. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3913–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Relat, J.; Hondares, E.; Pérez-Martí, A.; Ribas, F.; Villarroya, F.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D. FGF21 Mediates the Lipid Metabolism Response to Amino Acid Starvation. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1786–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Marti, A.; Garcia-Guasch, M.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Carrilho-Do-Rosario, A.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D.; et al. A Low-Protein Diet Induces Body Weight Loss and Browning of Subcutaneous White Adipose Tissue through Enhanced Expression of Hepatic Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21). Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeckli, B.; Pham, T.-V.; Slits, F.; Latrille, S.; Peloso, A.; Delaune, V.; Oldani, G.; Lacotte, S.; Toso, C. FGF21 Negatively Affects Long-Term Female Fertility in Mice. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, B.M.; Bookout, A.L.; Ding, X.; Lin, V.Y.; Atkin, S.D.; Gautron, L.; Kliewer, S.A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. FGF21 Contributes to Neuroendocrine Control of Female Reproduction. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshi, Y.; Shao, W.; Liu, D.; Tian, L.; Pang, J.; Gu, J.; Hu, J.; Jin, T. Estrogen-Wnt Signaling Cascade Regulates Expression of Hepatic Fibroblast Growth Factor 21. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E292–E304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, M.; Song, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, S.; Che, L.; Fang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Jin, C.; Feng, B.; et al. Dietary Protein Regulates Female Estrous Cyclicity Partially via Fibroblast Growth Factor 21. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Makishima, M.; Bhawal, U.K. Differentiated Embryo Chondrocyte 1 (DEC1) Is a Novel Negative Regulator of Hepatic Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21) in Aging Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Ostan, R.; Fabbri, C.; Santoro, A.; Guidarelli, G.; Vitale, G.; Mari, D.; Sevini, F.; Capri, M.; Sandri, M.; et al. Human Aging and Longevity Are Characterized by High Levels of Mitokines. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2019, 74, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Epel, E. Stress and Telomere Shortening: Insights from Cellular Mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 73, 101507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.T.; Dumitriu, B. Telomere Dynamics in Mice and Humans. Semin. Hematol. 2013, 50, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.P.; Fouquerel, E.; Opresko, P.L. The Impact of Oxidative DNA Damage and Stress on Telomere Homeostasis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2019, 177, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgård, C.; Benetos, A.; Verhulst, S.; Labat, C.; Kark, J.D.; Christensen, K.; Kimura, M.; Kyvik, K.O.; Aviv, A. Leukocyte Telomere Length Dynamics in Women and Men: Menopause vs Age Effects. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.; Bann, D.; Wiley, L.; Cooper, R.; Hardy, R.; Nitsch, D.; Martin-Ruiz, C.; Shiels, P.; Sayer, A.A.; Barbieri, M.; et al. Gender and Telomere Length: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 51, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de la Puente, M.; Valle-Hita, C.; Salas-Huetos, A.; Martínez, M.Á.; Sánchez-Resino, E.; Canudas, S.; Torres-Oteros, D.; Relat, J.; Babio, N.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Sperm and Leukocyte Telomere Length Are Related to Sperm Quality Parameters in Healthy Men from the Led-Fertyl Study. Hum. Reprod. Open 2024, 2024, hoae062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.S.; Huh, J.Y.; Hwang, I.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.B. Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Judd, R.L. Adiponectin Regulation and Function. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1031–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Jia, Y.; Fu, T.; Viswakarma, N.; Bai, L.; Rao, M.S.; Zhu, Y.; Borensztajn, J.; Reddy, J.K. Sustained Activation of PPARα by Endogenous Ligands Increases Hepatic Fatty Acid Oxidation and Prevents Obesity in Ob/Ob. Mice. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougerat, A.; Schoiswohl, G.; Polizzi, A.; Régnier, M.; Wagner, C.; Smati, S.; Fougeray, T.; Lippi, Y.; Lasserre, F.; Raho, I.; et al. ATGL-Dependent White Adipose Tissue Lipolysis Controls Hepatocyte PPARα Activity. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundåsen, T.; Hunt, M.C.; Nilsson, L.M.; Sanyal, S.; Angelin, B.; Alexson, S.E.H.; Rudling, M. PPARα Is a Key Regulator of Hepatic FGF21. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 360, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, T.P.; Pajvani, U.B.; Berg, A.H.; Lin, Y.; Jelicks, L.A.; Laplante, M.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Rajala, M.W.; Parlow, A.F.; Cheeseboro, L.; et al. A Transgenic Mouse with a Deletion in the Collagenous Domain of Adiponectin Displays Elevated Circulating Adiponectin and Improved Insulin Sensitivity. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B.; Nishida, M.; Kaimoto, K.; Asakawa, A.; Chaolu, H.; Cheng, K.-C.; Li, Y.-X.; Terashi, M.; Koyama, K.I.; Amitani, H.; et al. Effects of Aging on the Plasma Levels of Nesfatin-1 and Adiponectin. Biomed. Rep. 2014, 2, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bautista, R.; Alarcón-Aguilar, F.; Escobar-Villanueva, M.D.C.; Almanza-Pérez, J.; Merino-Aguilar, H.; Fainstein, M.; López-Diazguerrero, N. Biochemical Alterations during the Obese-Aging Process in Female and Male Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)-Treated Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11473–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillman, E.J.; Rolph, T. FGF21: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Related Metabolic Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 601290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Schönke, M.; Spoorenberg, B.; Lambooij, J.M.; van der Zande, H.J.; Zhou, E.; Tushuizen, M.E.; Andreasson, A.-C.; Park, A.; Oldham, S.; et al. FGF21 Protects against Hepatic Lipotoxicity and Macrophage Activation to Attenuate Fibrogenesis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. eLife 2023, 12, e83075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Xia, A.; Meng, F.; Chunyu, J.; Sun, X.; Ren, G.; Yu, D.; Jiang, X.; Tang, L.; Xiao, W.; et al. FGF21 Alleviates Chronic Inflammatory Injury in the Aging Process through Modulating Polarization of Macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 96, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Song, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, D.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Attenuates Hepatic Fibrogenesis through TGF-β/Smad2/3 and NF-ΚB Signaling Pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 290, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, J.; Ji, S.; Ma, F.; Wang, G.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Han, J.; Tai, P.; et al. The Effects of B1344, a Novel Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Analog, on Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Nonhuman Primates. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, V.; Jambrina, C.; Casana, E.; Sacristan, V.; Muñoz, S.; Darriba, S.; Rodó, J.; Mallol, C.; Garcia, M.; León, X.; et al. FGF21 Gene Therapy as Treatment for Obesity and Insulin Resistance. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, EMMM201708791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Friedman, S.L.; Hoshida, Y. Hepatic Stellate Cells as Key Target in Liver Fibrosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 121, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Madden, P.; Gu, J.; Xing, X.; Sankar, S.; Flynn, J.; Kroll, K.; Wang, T. Uncovering the Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Landscape of Nicotinic Receptor Genes in Non-Neuronal Tissues. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlein, C.; Talukdar, S.; Heine, M.; Fischer, A.W.; Krott, L.M.; Nilsson, S.K.; Brenner, M.B.; Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. FGF21 Lowers Plasma Triglycerides by Accelerating Lipoprotein Catabolism in White and Brown Adipose Tissues. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, A.T.; Larson, K.R.; Huang, K.-P.; Wu, C.-T.; Godoroja, N.; Fang, Y.; Jayakrishnan, D.; Soto Sauza, K.A.; Sims, L.C.; Mohajerani, N.; et al. FGF21 Controls Hepatic Lipid Metabolism via Sex-Dependent Interorgan Crosstalk. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e155848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Shao, X.; Zeng, H.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Peng, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Hua, L.; Meng, F.; Han, X. Hepatic-Specific FGF21 Knockout Abrogates Ovariectomy-Induced Obesity by Reversing Corticosterone Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.-N.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kim, J.-D.; Oh, J.Y.; Jung, Y.-S. Sex-Specific Metabolic Interactions between Liver and Adipose Tissue in MCD Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46959–46971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oraha, J.; Enriquez, R.F.; Herzog, H.; Lee, N.J. Sex-Specific Changes in Metabolism during the Transition from Chow to High-Fat Diet Feeding Are Abolished in Response to Dieting in C57BL/6J Mice. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonardo, A.; Nascimbeni, F.; Ballestri, S.; Fairweather, D.L.; Win, S.; Than, T.A.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Suzuki, A. Sex Differences in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: State of the Art and Identification of Research Gaps. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, A.; Ida, K. Liver Injury and Cell Survival in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Regulated by Sex-Based Difference through B Cell Lymphoma 6. Cells 2022, 11, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, N.J.; Dhillon, V.S.; Thomas, P.; Fenech, M. A Quantitative Real-Time PCR Method for Absolute Telomere Length. Biotechniques 2008, 44, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torres-Oteros, D.; Nicola-Llorente, M.; Sanz-Lamora, H.; Pérez-Martí, A.; Marrero, P.F.; Canudas, S.; Haro, D.; Relat, J. Hepatic FGF21 Deletion Improves Glucose Metabolism, Alters Lipogenic and Chrna4 Gene Expression, and Enhances Telomere Maintenance in Aged Female Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010194

Torres-Oteros D, Nicola-Llorente M, Sanz-Lamora H, Pérez-Martí A, Marrero PF, Canudas S, Haro D, Relat J. Hepatic FGF21 Deletion Improves Glucose Metabolism, Alters Lipogenic and Chrna4 Gene Expression, and Enhances Telomere Maintenance in Aged Female Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010194

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Oteros, Daniel, Mariano Nicola-Llorente, Héctor Sanz-Lamora, Albert Pérez-Martí, Pedro F. Marrero, Silvia Canudas, Diego Haro, and Joana Relat. 2026. "Hepatic FGF21 Deletion Improves Glucose Metabolism, Alters Lipogenic and Chrna4 Gene Expression, and Enhances Telomere Maintenance in Aged Female Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010194

APA StyleTorres-Oteros, D., Nicola-Llorente, M., Sanz-Lamora, H., Pérez-Martí, A., Marrero, P. F., Canudas, S., Haro, D., & Relat, J. (2026). Hepatic FGF21 Deletion Improves Glucose Metabolism, Alters Lipogenic and Chrna4 Gene Expression, and Enhances Telomere Maintenance in Aged Female Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010194