Fine Structure Investigation and Laser Cooling Study of the CdBr Molecule

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

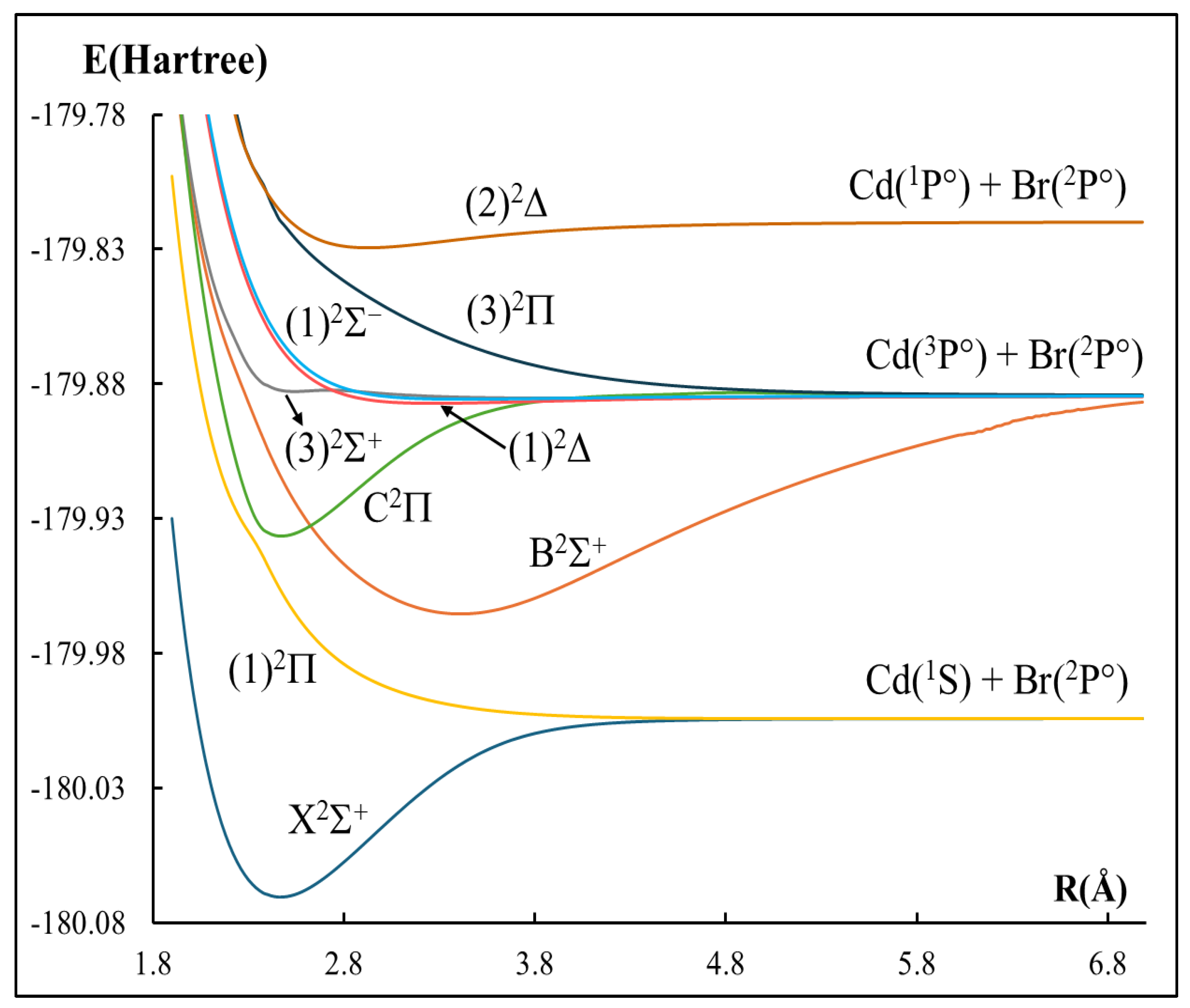

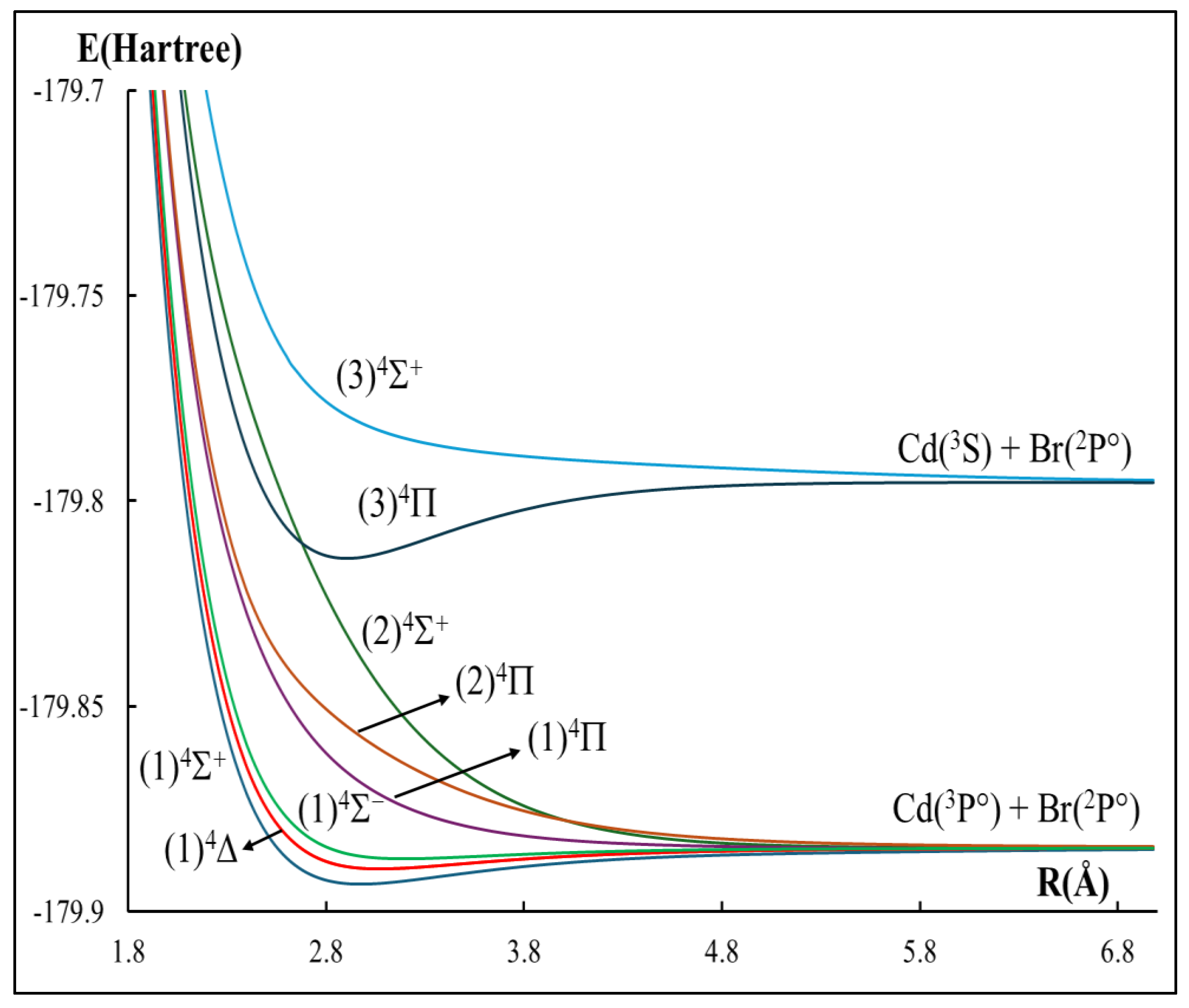

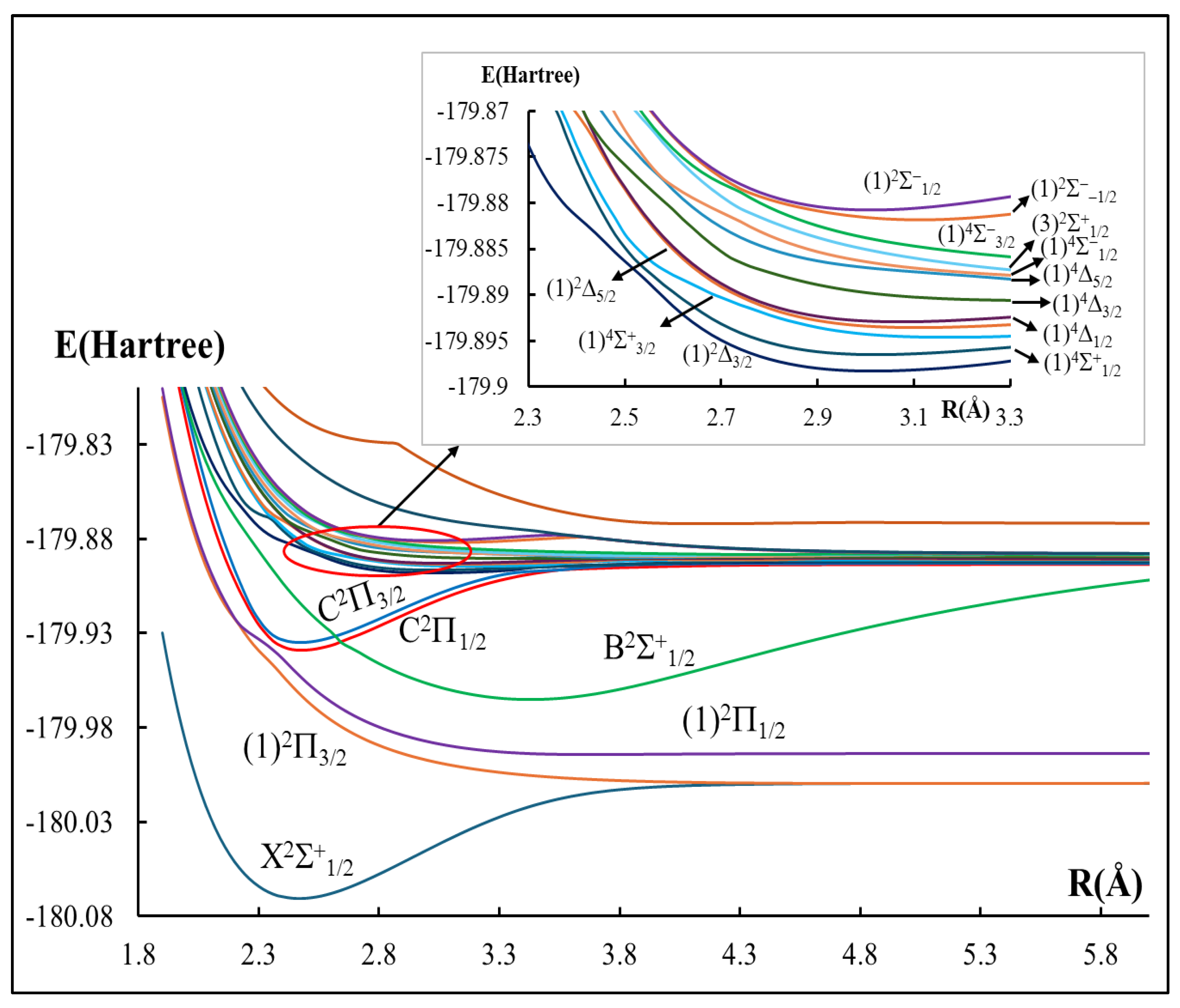

2.1. The Potential Energy Curves and Spectroscopic Constants

2.2. Rovibrational Calculations

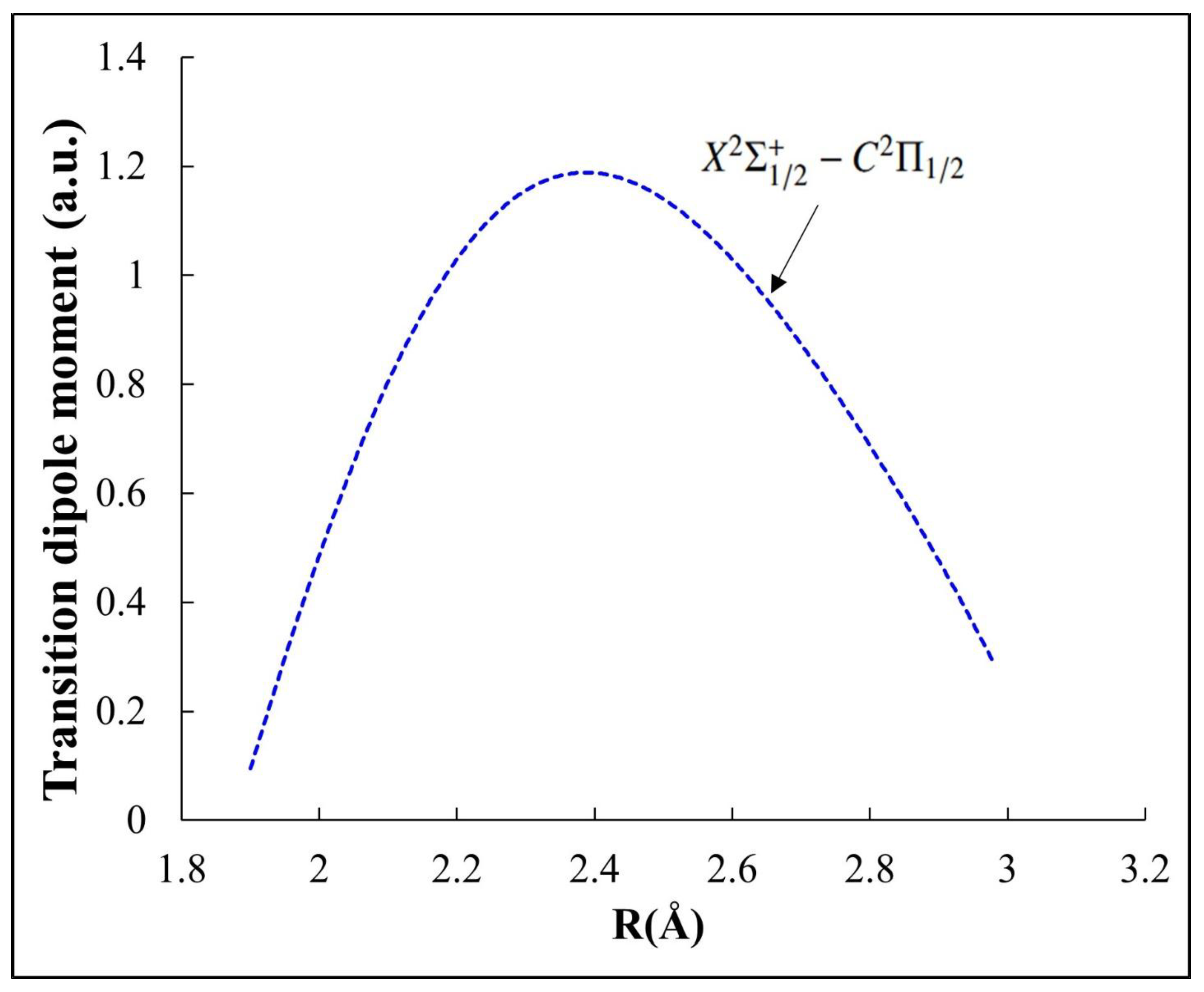

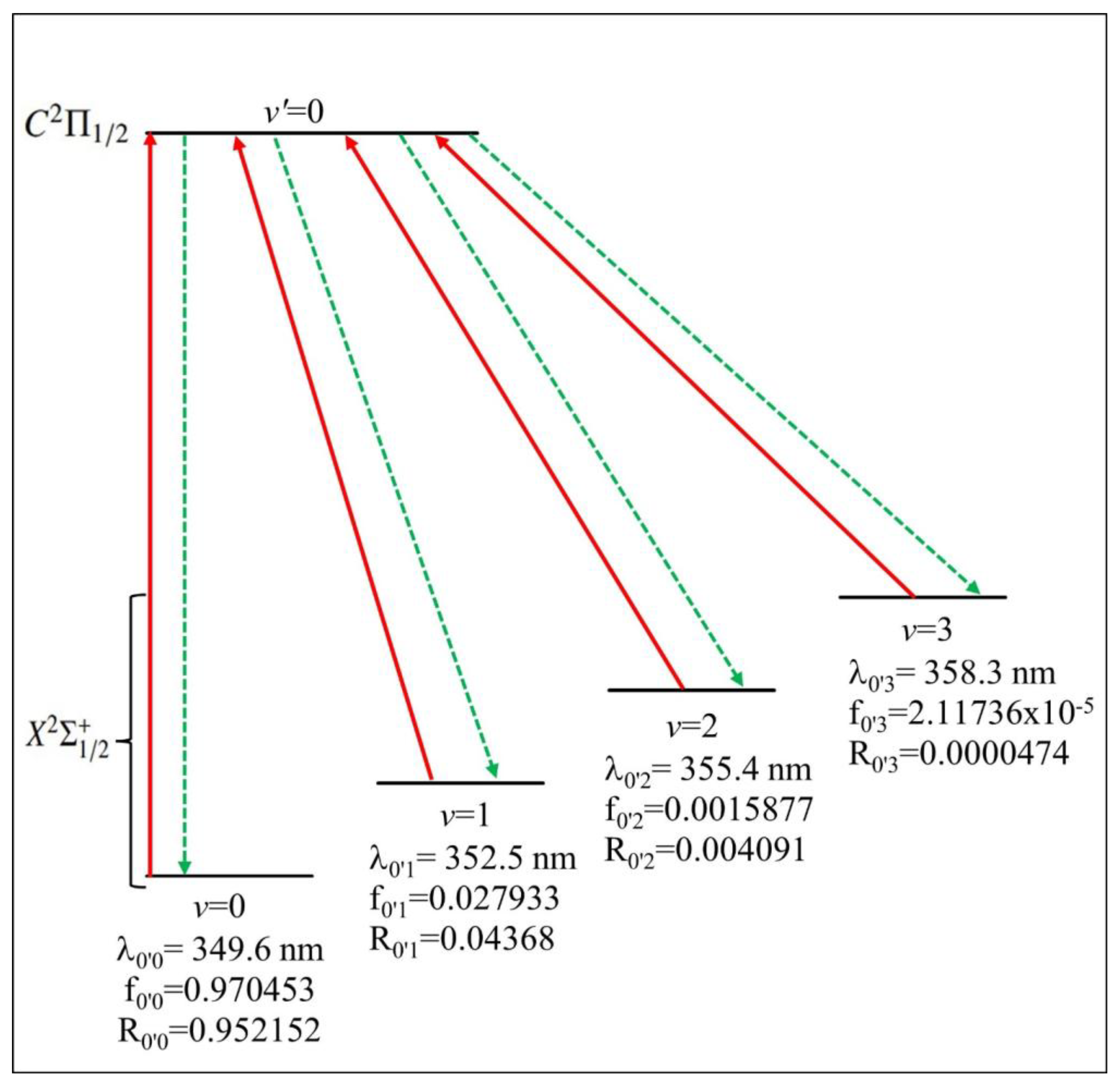

2.3. Transition Properties and Laser Cooling Scheme

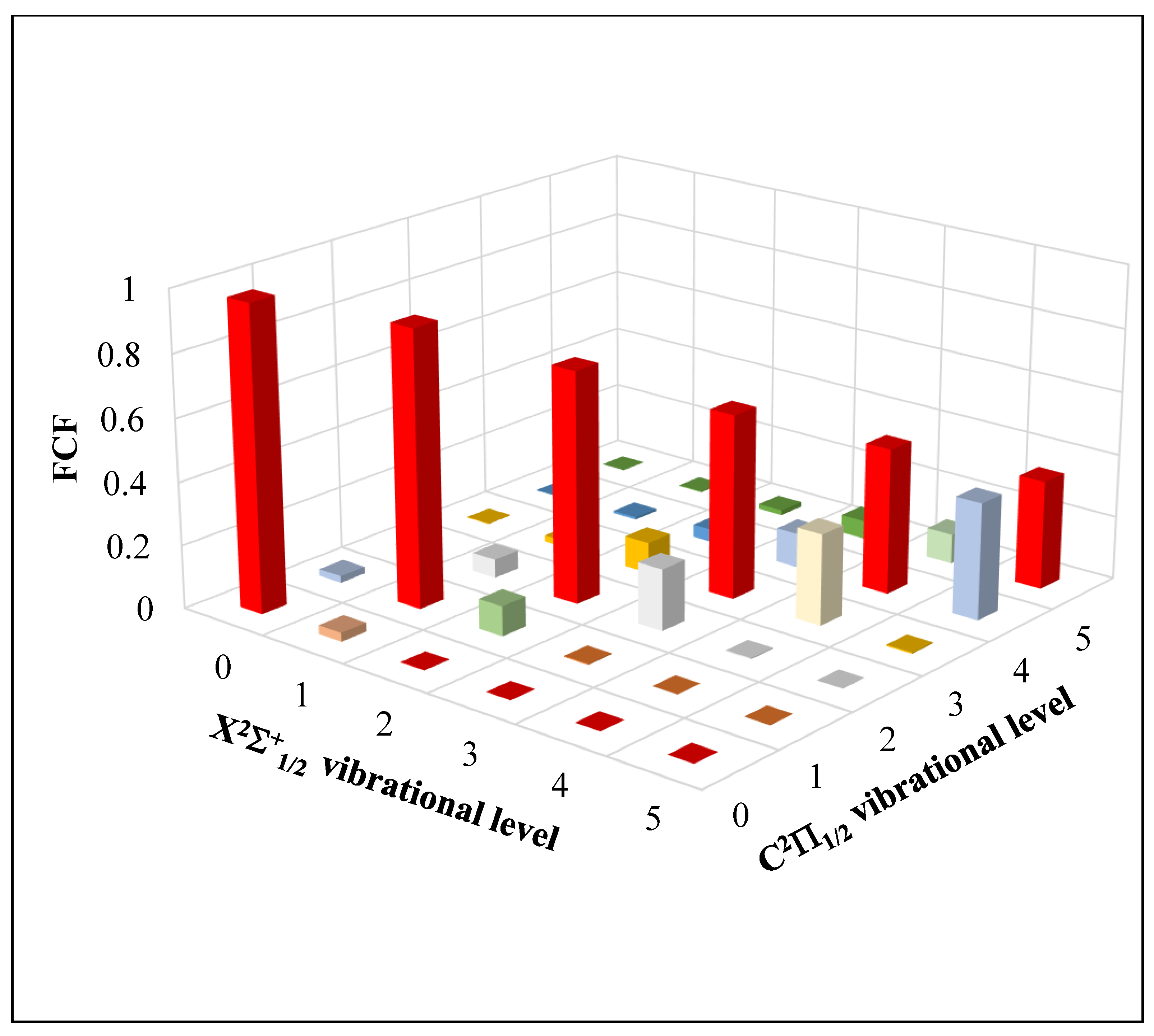

2.3.1. Highly Diagonal Franck–Condon Array

2.3.2. Absence of Intervening Electronic States

2.3.3. Short Radiative Lifetimes

- (1)

- Our calculations show a Te value for the state C2Π1/2 that differs by about 1400 cm−1 with respect to previous experimental work. Even though minimal when taking into account the state C2Π1/2 is a high-lying state, ~30,000 cm−1 above the ground state, such a difference has still to be considered when setting up pumping laser wavelengths.

- (2)

- The calculated harmonic vibrational frequency ωe, shows very good agreement with the experiment for the ground X2Σ+1/2 and C2Π3/2 states. An experimental validation of the same parameter for the C2Π1/2 state is highly recommended.

- (3)

- A preliminary investigation of the position of the vibrational level v′ = 0 has shown no crossings with the neighboring C2Π3/2 and B2Σ+1/2; however, a direct confirmation is yet to be made available.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlson, K.D.; Claydon, C.R. Advances in High Temperature Chemistry; Eyring, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.Q.; Rao, G.N. Chemical fractionation of cadmium, copper, nickel, and zinc in contaminated soils. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A.; Ayodele, E.T.; Oyedirdan, G.O.; Oluyemi, E.A. Levels and speciation of heavy metals in soils of industrial southern Nigeria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2003, 85, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediger, M.N.; McCown, A.W.; Eden, J.G. CdI and CdBr photodissociation lasers at 655 and 811 nm: CdI spectrum identification and enhanced laser output with 114CdI2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1982, 40, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.R.; Harrison, R.M. Cadmium in the atmosphere. Experientia 1984, 40, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewers, J.M.; Barry, P.J.; MacGregor, D.J. Distribution and cycling of cadmium in the environment. Adv. Environ. Sci. Tech. 1987, 19, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Krems, R.V. Molecules near absolute zero and external field control of atomic and molecular dynamics. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2005, 24, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.D.; deCarvalho, R.; Guillet, T.; Friedrich, B.; Doyle, J.M. Magnetic trapping of calcium monohydride molecules at millikelvin temperatures. Nature 1998, 395, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, B.; Herschbach, D. Alignment and trapping of molecules in intense laser fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 4623–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, J.L.; Rey, A.M.; Ye, J. Cold molecules: Progress in quantum engineering of chemistry and quantum matter. Science 2017, 357, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, M. Sensitive measurement of mp/me variance using vibrational transition frequencies of cold molecules. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 055010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, E.R.; Lewandowski, H.J.; Sawyer, B.C.; Ye, J. Cold molecule spectroscopy for constraining the evolution of the fine-structure constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 143004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatt, R.; Gill, P.; Thompson, R.C. Current perspectives on the physics of trapped ions. J. Mod. Opt. 1992, 39, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddams, S.A.; Udem, T.; Bergquist, J.C.; Curtis, E.A.; Drullinger, R.E.; Hollberg, L.; Itano, W.M.; Lee, W.D.; Oates, C.W.; Vogel, K.R.; et al. An optical clock based on a single trapped 199Hg+ ion. Science 2001, 293, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, A.; Brennen, G.K.; Zoller, P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 2006, 2, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral, K.; Santos, L.; Lewenstein, M. Quantum phases of dipolar bosons in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 170406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.; Petrov, D.; Lukin, M.; Demler, E. Quantum magnetism with multicomponent dipolar molecules in an optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 190401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krems, R.V. Cold controlled chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 4079–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, L.D.; DeMille, D.; Krems, R.V.; Ye, J. Cold and ultracold molecules: Science, technology, and applications. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 055049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Cao, J.; Ma, H.; Bian, W. Laser cooling of copper monofluoride: A theoretical study including spin–orbit coupling. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 100568–100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Lin, Q.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, T.; Yin, J. Laser-cooled HgF as a promising candidate for measuring the electric dipole moment of the electron. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 032502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaev, T.A.; Hoekstra, S.; Berger, R. Laser-cooled RaF as a promising candidate to measure molecular parity violation. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 052521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cui, J.; Li, R.; Yan, B. Configuration interaction study of electronic structures of CdCl including spin–orbit coupling. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 677, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Gomes, A.S.P. Reassessing the potential of TlCl for laser cooling experiments via four-component correlated electronic structure calculations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, C.; Deselnicu, M.; Mukarakate, C.; Reid, S.A. Electronic spectroscopy of the à 1 A″ ↔ 1 A′ system of CDBr. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 094305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoussaoui, S.; Korek, M. Electronic structure with dipole moment calculation of the low-lying electronic states of the molecule ZnI. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2015, 161, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoussaoui, S.; El-Kork, N.; Korek, M. Electronic structure of the ZnCl molecule with rovibrational and ionicity studies of the ZnX (X = F, Cl, Br, I) compounds. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1090, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoussaoui, S.; El-Kork, N.; Korek, M. Electronic structure with dipole moment and ionicity calculations of the low-lying electronic states of the ZnF molecule. Can. J. Chem. 2017, 95, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoussaoui, S.; Chmaisani, W.; Korek, M. Theoretical electronic structure with dipole moment and rovibrational calculation of the low-lying electronic states of the HgF molecule. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 201, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoussaoui, S.; Korek, M. Electronic structure with dipole moment calculation of the low-lying electronic states of ZnBr molecule. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2015, 1068, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreddine, K.; Korek, M. Theoretical electronic structure of the cadmium monohalide molecules CdX (X = F, Cl, Br, I). AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, K.P.; Herzberg, G. Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure. IV. In Constants of Diatomic Molecules; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, K. Bandenspektren der Quecksilber-, Cadmium- und Zinkhalogenide. Helv. Phys. Acta 1929, 2, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, H.G. The ultraviolet spectra and electron configuration of HgF and related halide molecules. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1943, 182, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gosavi, R.K.; Greig, G.; Young, P.J.; Strausz, O.P. Reactions of metal atoms. IV. The UV spectra of CdBr, CdI, ZnBr, and ZnI. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Schwarz, W.H.E. Properties and stabilities of MX, MX2, and M2X2 compounds (M = Zn, Cd, Hg; X = F, Cl, Br, I). Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 5597–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepler, B.C.; Peterson, K.A. Chemically accurate thermochemistry of cadmium: An ab initio study of Cd + XY (X = H, O, Cl, Br; Y = Cl, Br). J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12321–12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, M.Y.; Wu, Z.J.; Su, Z.M. Electronic structures and chemical bonding in 4d transition metal monohalides. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 2190–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, M.; Zhao, S.; Zu, N.; Yan, B. Spin–orbit calculations on the ground and excited electronic states of CdBr molecule. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2018, 221, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, W.L. The NIST atomic spectra database. AIP Conf. Proc. 2000, 543, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaev, B.F.; Knuts, S.; Ågren, H. On the interpretation of the external heavy atom effect on singlet–triplet transitions. Chem. Phys. 1994, 181, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhai, H.S.; Liu, Y.F. Accurate predictions of spectroscopic and molecular properties of the NTe molecule. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 202, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kher, N.A.; Korek, M.; Alharzali, N.; El-Kork, N. Electronic structure with spin–orbit coupling effect of HfH molecule for laser cooling investigations. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 314, 124106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kher, N.A.; El-Kork, N.; Alharzali, N.; Assaf, J.; Korek, M. Fine structure investigation and laser cooling study of the LaH molecule. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 41699–41709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Carrington, A. Rotational Spectroscopy of Diatomic Molecules; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bernath, P.F. Spectra of Atoms and Molecules, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch, C.M.; Kurtz, L.; de Vivie-Riedle, R. Applying optimal control theory for elements of quantum computation in molecular systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 343, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korek, M.; Kobeissi, H. New analytical expression for the rotational factor in Raman transitions. Can. J. Phys. 1995, 73, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korek, M.; Kobeissi, H. Highly accurate diatomic centrifugal distortion constants for high orders and high levels. J. Comput. Chem. 1992, 13, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korek, M. A one directional shooting method for the computation of diatomic centrifugal distortion constants. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1999, 119, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Vilas, N.B.; Hallas, C.; Anderegg, L.; Augenbraun, B.L.; Baum, L.; Miller, C.; Raval, S.; Doyle, J.M. Direct laser cooling of a symmetric top molecule. Science 2020, 369, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeshko, M.; Krems, R.V.; Doyle, J.M.; Kais, S. Manipulation of molecules with electromagnetic fields. Mol. Phys. 2013, 111, 1648–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prehn, A.; Ibrügger, M.; Glöckner, R.; Rempe, G.; Zeppenfeld, M. Optoelectrical cooling of polar molecules to submillikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 063005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gantner, T.; Koller, M.; Zeppenfeld, M.; Chervenkov, S.; Rempe, G. A cryofuge for cold-collision experiments with slow polar molecules. Science 2017, 358, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Vashishta, M.; Djuricanin, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhong, W.; Mittertreiner, T.; Carty, D.; Momose, T. Magnetic trapping of cold methyl radicals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 093201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, K.-K.; Ospelkaus, S.; de Miranda, M.H.G.; Pe’er, A.; Neyenhuis, B.; Zirbel, J.J.; Kotochigova, S.; Julienne, P.S.; Jin, D.S.; Ye, J. A high phase-space-density gas of polar molecules. Science 2008, 322, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, L.; Valtolina, G.; Matsuda, K.; Tobias, W.G.; Covey, J.P.; Ye, J. A degenerate Fermi gas of polar molecules. Science 2019, 363, 853–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, E.S.; Barry, J.F.; DeMille, D. Laser cooling of a diatomic molecule. Nature 2010, 467, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truppe, S.; Williams, H.J.; Hambach, M.; Caldwell, L.; Fitch, N.J.; Hinds, E.A.; Sauer, B.E.; Tarbutt, M.R. Molecules cooled below the Doppler limit. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, L.; Augenbraun, B.L.; Chae, E.; Hemmerling, B.; Hutzler, N.R.; Ravi, A.; Collopy, A.; Ye, J.; Ketterle, W.; Doyle, J.M. Radio frequency magneto-optical trapping of CaF with high density. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collopy, A.L.; Ding, S.; Wu, Y.; Finneran, I.A.; Anderegg, L.; Augenbraun, B.L.; Doyle, J.M.; Ye, J. 3D magneto-optical trap of yttrium monoxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 213201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyryev, I.; Baum, L.; Matsuda, K.; Augenbraun, B.L.; Anderegg, L.; Sedlack, A.P.; Doyle, J.M. Sisyphus laser cooling of a polyatomic molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 173201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augenbraun, B.L.; Lasner, Z.D.; Frenett, A.; Sawaoka, H.; Miller, C.; Steimle, T.C.; Doyle, J.M. Laser-cooled polyatomic molecules for improved electron electric dipole moment searches. New J. Phys. 2020, 22, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, L.; Vilas, N.B.; Hallas, C.; Augenbraun, B.L.; Raval, S.; Mitra, D.; Doyle, J.M. 1D magneto-optical trap of polyatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 133201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rosa, M.D. Laser-cooling molecules: Concept, candidates, and supporting hyperfine-resolved measurements of rotational lines in the AX (0, 0) band of CaH. Eur. Phys. J. D 2004, 31, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kork, N.; AlMasri Alwan, A.; Abu El Kher, N.; Assaf, J.; Ayari, T.; Alhseinat, E.; Korek, M. Laser cooling with intermediate state of spin–orbit coupling of LuF molecule. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Guo, H.J.; Wang, Y.M.; Xue, J.L.; Xu, H.F.; Yan, B. Laser-cooling with an intermediate electronic state: Theoretical prediction on bismuth hydride. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 224305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassine, K.; El Kork, N.; Abu El Kher, N.; Younes, G.; Korek, M. Theoretical study of spin–orbit coupling and laser cooling for HBr molecule with first-overtone spectral calculations. Front. Phys. 2025, 13, 1635859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, F.; Chmaisani, W.; Younes, G.; El-Kork, N.; Korek, M. Theoretical spin–orbit laser cooling for AlZn molecule. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 154305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.S.; Gao, T. The feasibility of laser cooling: An ab initio investigation of MgBr, MgI, and MgAt molecules. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 231, 118107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, R.J. LEVEL: A computer program for solving the radial Schrödinger equation for bound and quasibound levels. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 186, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.-J.; Knowles, P.J. Getting Started with MOLPRO, Version 2015.1; Molpro.net: Cardiff, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.molpro.net (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Li, R.; Yuan, X.; Liang, G.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, B. Laser cooling of the SiO+ molecular ion: A theoretical contribution. Chem. Phys. 2019, 525, 110412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, H.J.; van der Straten, P. Laser cooling and trapping of atoms. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2003, 20, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, J.F. Laser Cooling and Slowing of a Diatomic Molecule. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H.-J.; Knowles, P.J. An efficient internally contracted multiconfiguration–reference configuration interaction method. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 5803–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, A.R. Gabedit—A graphical user interface for computational chemistry softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figgen, D.; Rauhut, G.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H. Energy-consistent pseudopotentials for group 11 and 12 atoms: Adjustment to multi-configuration Dirac–Hartree–Fock data. Chem. Phys. 2005, 311, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Puzzarini, C. Systematically convergent basis sets for transition metals. II. Pseudopotential-based correlation consistent basis sets for the group 11 (Cu, Ag, Au) and 12 (Zn, Cd, Hg) elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2005, 114, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, H.; Metz, B.; Dolg, M. Relativistic energy-consistent pseudopotentials—Recent developments. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Atomic States Cd + Br | Molecular States CdBr | Energy Separation (cm−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etheo. a | Eexp. b | % Relative Error | ||

| Cd (4d105s2, 1S) + Br (4s24p5, 2P°) | X2Σ+, (1)2Π | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cd (4d105s5p, 3P°) + Br (4s24p5, 2P°) | B2Σ+, X2Π, (1)4Δ, (1)4Σ+, (3)2Σ+, (1)2Δ, (1)4Σ−, (1)4Π, (2)4Π, (2)4Σ+ (3)2Π, (1)2Σ− | 26,245.15 | 31,246.335 | 16.0 |

| Cd (4d105s5p, 1P°) + Br (4s24p5, 2P°) | (2)2Δ | 40,452.05 | 43,692.384 | 7.4 |

| Cd (4d105s6s, 3S) + Br (4s24p5, 2P°) | (3)4Π, (3)4Σ+ | 45,889.49 | 51,483.980 | 10.9 |

| State | Ref. | Te (cm−1) | Re (Å) | ωe (cm−1) | Be (cm−1) | (cm−1) | De (cm−1) | µe (a.u) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2Σ+ | Exp. [32] | 0 | - | 230.5 | - | - | 7258–12,904 | |

| This work | 0 | 2.468 | 231.4 (−0.9) | 5.928 | 0.2483 | 14,552 | 1.196 | |

| Calc. [36] | 0 | 2.52 | 214 (16.5) | - | - | - | - | |

| Calc. [37] | 0 | 2.4664 | 233.2 (−2.7) | - | - | 11,856 | - | |

| Calc. [38] | 0 | 2.563 | 198 (32.5) | - | - | 11,130 | 1.395 | |

| Calc. [31] | 0 | 2.564 | 210.5 (20) | 5.48 | - | - | ||

| Calc. [39] * | 0 | 2.4738 | 227.7 (2.8) | 5.91 | - | 12,098 | - | |

| Calc. [39] ** | 0 | 2.5206 | 223.3 (7.2) | 5.69 | - | 14,840 | - | |

| B2Σ+ | This work | 23,033 | 3.410 | 118.4 | 3.104 | - | 17,771 | 1.555 |

| Calc. [31] | 19,528 | 3.4679 | 119.0 | 3.00 | - | - | ||

| Calc. [39] * | 22,272 | 3.2646 | 133.9 | 3.39 | - | 19,841 | - | |

| Calc. [39] ** | 21,573 | 3.5386 | 113.2 | 2.89 | - | 20,405 | - | |

| C2Π | Exp. [32] | 31,075 | - | 254.5 | - | - | - | - |

| This work | 29,340 (1735) | 2.466 | 268.0 (−13.5) | 5.939 | 0.7678 | 11,441 | 1.013 | |

| Calc. [31] | 28,850 (2225) | 2.5522 | 222.1 (32.4) | 5.53 | - | - | - | |

| Calc. [39] * | 30,688 (387) | 2.4462 | 243.2 (11.3) | 6.04 | - | 11,533 | - | |

| Calc. [39] ** | 30,333 (742) | 2.4973 | 259.4 (−4.9) | 5.80 | - | 11,937 | - | |

| (1)4Σ+ | This work | 38,853 | 2.975 | 85.1 | 4.078 | 0.5183 | 1933 | 0.860 |

| Calc. [31] | 35,937 | 3.3823 | 46.9 | 3.13 | - | -- | - | |

| Calc. [39] * | 40,395 | 3.0194 | 77.2 | 3.97 | - | 1774 | - | |

| (1)4Δ | This work | 39,683 | 3.071 | 68.9 | 3.827 | 0.5121 | 1123 | 0.829 |

| Calc. [31] | 36,491 | 3.6213 | 32.3 | 2.75 | - | - | - | |

| Calc. [39] * | 41,035 | 3.1112 | 64.5 | 3.74 | - | 1209 | - | |

| (1)2Δ | This work | 40,220 | 3.267 | 49.3 | 3.349 | 1.8016 | 587 | 0.624 |

| Calc. [31] | 36,647 | 4.0051 | 24.8 | 2.26 | - | - | - | |

| Calc. [39] * | 41,475 | 3.3015 | 45.8 | 3.32 | - | 725 | - | |

| (1)4Σ− | This work | 40,243 | 3.194 | 51.0 | 3.538 | 0.8123 | 568 | 0.733 |

| Calc. [39] * | 41,504 | 3.2263 | 51.5 | 3.48 | - | 725 | - | |

| (1)2Σ− | This work | 40,548 | 3.428 | 29.9 | 3.069 | 0.9923 | 263 | 0.536 |

| Calc. [31] | 36,803 | 4.4471 | - | 1.68 | - | - | - | |

| Calc. [39] * | 41,730 | 3.3858 | 38.6 | 3.15 | - | 483 | - | |

| (3)4Π | This work | 56,280 | 2.904 | 128.6 | 4.278 | 0.2765 | 4050 | 0.784 |

| Calc. [31] | 54,565 | 3.0514 | 99.99 | 3.88 | - | - | 1.7874 |

| Atomic State | Possible Ω States | Relative Energy (cm−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Work | Exp. [40] | % Relative Error | ||

| Cd (1S) + Br (2P3/2) | 1/2, 3/2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cd (1S) + Br (2P1/2) | 1/2 | 3580.42 | 3685.24 | 2.8 |

| Cd (3P0) + Br (2P3/2) | 1/2, 3/2 | 25,634.94 | 30,113.990 | 14.9 |

| Cd (3P1) + Br (2P3/2) | 5/2, 3/2, 3/2, 1/2, 1/2, 1/2 | 26,586.12 | 30,656.087 | 13.8 |

| State | Ref. | Te (cm−1) | Re (Å) | ωe (cm−1) | Be × 102 (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2Σ+1/2 | Exp. [32] | - | 230.5 | - | |

| This work | 0.0 | 2.468 | 230.6 (−0.1) | 5.92 | |

| Calc. [36] | 2.52 | 214.0 (16.5) | - | ||

| Calc. [37] | 2.4664 | 233.2 (−2.7) | - | ||

| Calc. [38] | 2.563 | 198 (32.5) | - | ||

| Calc. [31] | 2.564 | 210.5 (20) | 5.48 | ||

| Calc. [39] | 2.4749 | 226.8 (3.7) | - | ||

| (1)2Π1/2 | This work | 16,798 | 3.681 | 40.3 | 2.66 |

| B2Σ+1/2 | This work | 23,143 | 3.431 | 118.1 | 3.07 |

| Calc. [39] | 22,263 | 3.2798 | 133.3 | 3.36 | |

| C2Π1/2 | Exp. [32] | 30,300 | - | - | - |

| This work | 28,860 (1440) | 2.475 | 271.1 | 5.89 | |

| Calc. [39] | 30,140 (160) | 2.4582 | 199.8 | 5.64 | |

| C2Π3/2 | Exp. [32] | 31,463 | - | 253.8 | - |

| This work | 29,790 (1673) | 2.469 | 254.0 (−0.2) | 5.92 | |

| Calc. [39] | 31,148 (315) | 2.447 | 236.2 (17.6) | 6.05 | |

| (1)4Σ+1/2 | This work | 38,212 | 3.022 | 4.03 | 3.954 |

| (1)4Σ+3/2 | This work | 38,628 | 3.170 | 1.40 | 3.619 |

| (1)4Δ1/2 | This work | 39,001 | 3.072 | 9.00 | 3.825 |

| X2Σ1/2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v | Ev (cm−1) | Bv × 102 (cm−1) | Dv × 108 (cm−1) | Rmin (Å) | Rmax (Å) |

| 0 | 115.19 | 5.8462 | 1.4505 | 2.417 | 2.526 |

| 1 | 349.73 | 5.8373 | 1.5152 | 2.375 | 2.569 |

| 2 | 581.02 | 5.8211 | 1.3922 | 2.353 | 2.601 |

| 3 | 813.33 | 5.7900 | 1.1881 | 2.336 | 2.627 |

| 4 | 1049.29 | 5.7586 | 1.4168 | 2.320 | 2.652 |

| 5 | 1283.51 | 5.7470 | 1.6042 | 2.307 | 2.574 |

| 6 | 1513.97 | 5.7277 | 1.2946 | 2.295 | 2.695 |

| 7 | 1744.61 | 5.6985 | 1.3159 | 2.284 | 2.714 |

| 8 | 1974.77 | 5.6779 | 1.5293 | 2.274 | 2.733 |

| 9 | 2202.70 | 5.6614 | 1.4943 | 2.265 | 2.751 |

| 10 | 2428.84 | 5.6381 | 1.2984 | 2.256 | 2.769 |

| 11 | 2654.49 | 5.6127 | 1.4365 | 2.248 | 2.786 |

| 12 | 2878.74 | 5.5948 | 1.5606 | 2.240 | 2.802 |

| 13 | 3100.99 | 5.5740 | 1.3751 | 2.233 | 2.819 |

| 14 | 3322.25 | 5.5495 | 1.4202 | 2.226 | 2.835 |

| 15 | 3542.24 | 5.5290 | 1.5158 | 2.220 | 2.850 |

| 16 | 3760.60 | 5.5079 | 1.4508 | 2.213 | 2.866 |

| 17 | 3977.64 | 5.4854 | 1.4603 | 2.207 | 2.881 |

| 18 | 4193.31 | 5.4637 | 1.4804 | 2.202 | 2.896 |

| 19 | 4407.55 | 5.4416 | 1.4832 | 2.196 | 2.911 |

| 20 | 4620.39 | 5.4198 | 1.5030 | 2.191 | 2.926 |

| C2Π1/2 | |||||

| v | Ev (cm−1) | Bv × 102 (cm−1) | Dv × 108 (cm−1) | Rmin (Å) | Rmax (Å) |

| 0 | 133.93 | 5.8522 | 1.0877 | 2.430 | 2.534 |

| 1 | 403.34 | 5.8033 | 1.0410 | 2.401 | 2.580 |

| 2 | 672.20 | 5.7602 | 0.92432 | 2.381 | 2.615 |

| 3 | 944.52 | 5.7295 | 0.77253 | 2.368 | 2.639 |

| 4 | 1223.15 | 5.6966 | 0.85974 | 2.358 | 2.663 |

| 5 | 1500.68 | 5.6366 | 1.1576 | 2.348 | 2.689 |

| 6 | 1767.48 | 5.5764 | 1.0529 | 2.340 | 2.714 |

| 7 | 2029.13 | 5.5422 | 1.0365 | 2.333 | 2.737 |

| 8 | 2287.83 | 5.5088 | 1.0548 | 2.326 | 2.758 |

| 9 | 2543.54 | 5.4768 | 1.1232 | 2.319 | 2.779 |

| 10 | 2795.01 | 5.4347 | 0.99751 | 2.313 | 2.799 |

| 11 | 3044.11 | 5.4035 | 1.0633 | 2.308 | 2.819 |

| 12 | 3290.20 | 5.3635 | 1.1783 | 2.302 | 2.838 |

| 13 | 3532.47 | 5.3357 | 1.1823 | 2.297 | 2.857 |

| CdBr X2Σ+1/2 − C2Π1/2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ν′(C2Π1/2) = 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| ν (X2Σ+1/2) = 0 | Aν′v | 30,882,256.77 | 1,746,179.3 | 385,206.7187 | 127,778.62 | 42,465.012 | 13,967.007 | 4883.3049 |

| Rν′v | 0.95215209 | 0.02805663 | 0.00630063 | 0.00212631 | 0.00072613 | 0.00024938 | 0.00020192 | |

| ν = 1 | Aν′v | 1,416,739.24 | 55,179,978 | 4,685,587.143 | 1,408,663.4 | 551,980.73 | 209,044.62 | 76,279.25 |

| Rν′v | 0.04368046 | 0.88660102 | 0.07663978 | 0.02344095 | 0.00943862 | 0.00373242 | 0.00315406 | |

| ν = 2 | Aν′v | 132,692.0758 | 5,016,532.9 | 45,183,875.21 | 7,673,534 | 2,848,681.2 | 1,181,868.7 | 537,702.81 |

| Rν′v | 0.00409112 | 0.08060284 | 0.73904983 | 0.12769189 | 0.04871113 | 0.02110184 | 0.02223341 | |

| ν = 3 | Aν′v | 1537.496581 | 289,325.54 | 10,456,180.64 | 34,819,514 | 8,703,381.1 | 3,984,275.9 | 1,833,160.8 |

| Rν′v | 0.00004740 | 0.00464872 | 0.17102647 | 0.57941614 | 0.14882380 | 0.07113780 | 0.07579917 | |

| ν = 4 | Aν′v | 429.5835471 | 19.191812 | 397,518.6415 | 15,396,833 | 26,303,405 | 7,904,342.2 | 4,730,441.4 |

| Rν′v | 0.00001324 | 0.00000031 | 0.00650201 | 0.25621189 | 0.44977608 | 0.14112917 | 0.19559851 | |

| ν = 5 | Aν′v | 469.0557706 | 2659.4756 | 22,832.35746 | 519,034.52 | 19,480,616 | 18,272,568 | 7,084,431 |

| Rν′v | 0.00001446 | 0.00004273 | 0.00037346 | 0.00863702 | 0.33310954 | 0.32625008 | 0.29293337 | |

| ν = 6 | Aν′v | 39.50936826 | 2971.6815 | 6592.117738 | 148,781.89 | 550,582.32 | 24,441,791 | 9,917,546.6 |

| Rν′v | 0.00000122 | 0.00004775 | 0.00010782 | 0.00247581 | 0.00941470 | 0.43639932 | 0.41007956 | |

| Sum(s−1) = Aν′v | 32,434,163.73 | 62,237,666 | 61,137,792.82 | 60,094,139 | 58,481,112 | 56,007,857 | 24,184,445 | |

| τ:(s) = /Aν′v | 3.08317 × 10−8 | 1.607 × 10−8 | 1.63565 × 10−8 | 1.664 × 10−8 | 1.71 × 10−8 | 1.785 × 10−8 | 4.135 × 10−8 | |

| τ:(ns) | 30.83 | 16.07 | 16.36 | 16.64 | 17.10 | 17.85 | 41.35 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mostafa, A.; Zeid, I.; Abu El Kher, N.; El-Kork, N.; Korek, M. Fine Structure Investigation and Laser Cooling Study of the CdBr Molecule. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010184

Mostafa A, Zeid I, Abu El Kher N, El-Kork N, Korek M. Fine Structure Investigation and Laser Cooling Study of the CdBr Molecule. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010184

Chicago/Turabian StyleMostafa, Ali, Israa Zeid, Nariman Abu El Kher, Nayla El-Kork, and Mahmoud Korek. 2026. "Fine Structure Investigation and Laser Cooling Study of the CdBr Molecule" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010184

APA StyleMostafa, A., Zeid, I., Abu El Kher, N., El-Kork, N., & Korek, M. (2026). Fine Structure Investigation and Laser Cooling Study of the CdBr Molecule. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010184