Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Identify Medicarpin as a Potent CASP3 and ESR1 Binder Driving Apoptotic and Hormone-Dependent Anticancer Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

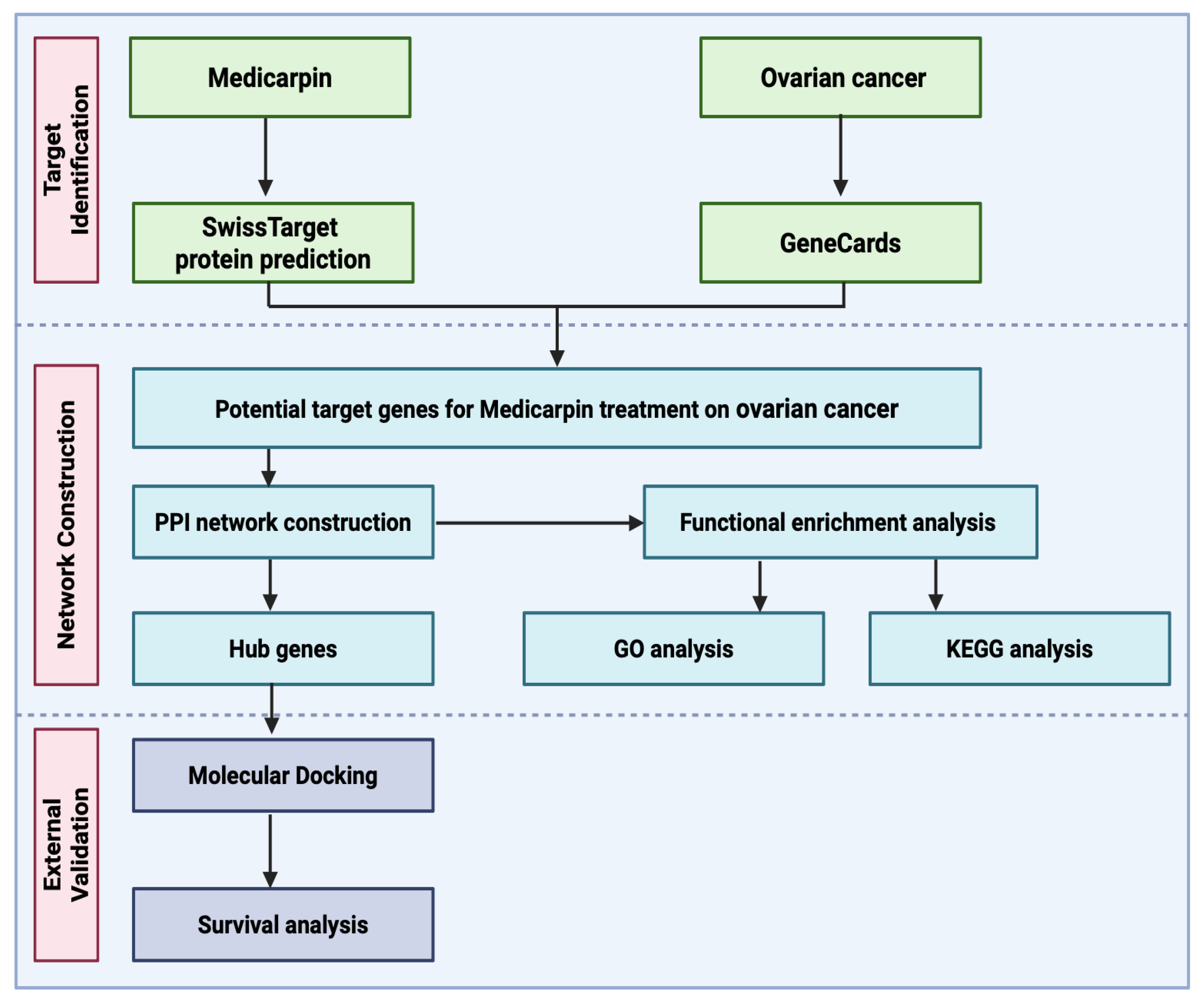

2.1. Workflow of Integrative Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Analysis for Medicarpin in Ovarian Cancer

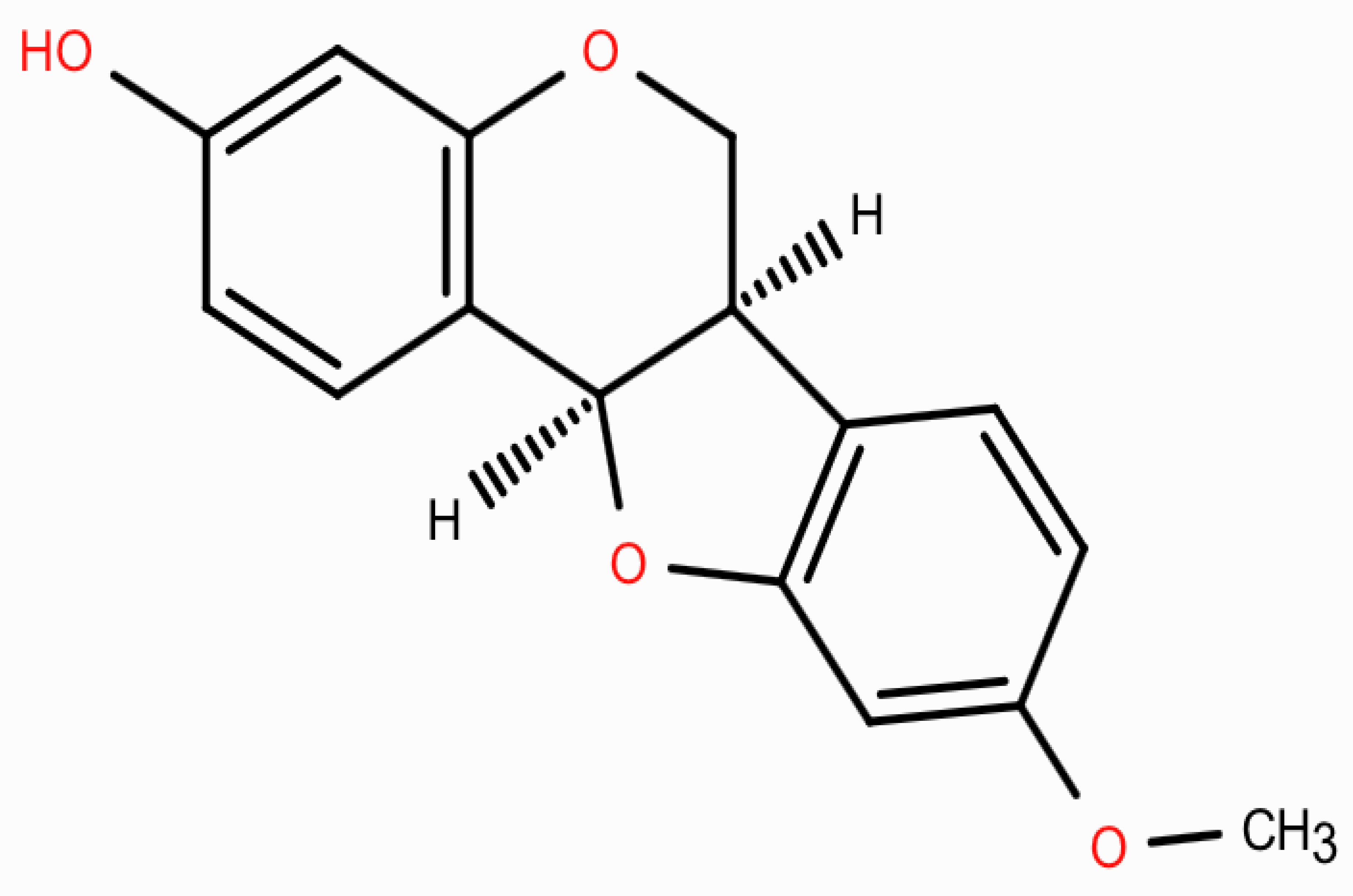

2.2. Physicochemical Properties and ADMET Characterization of Medicarpin

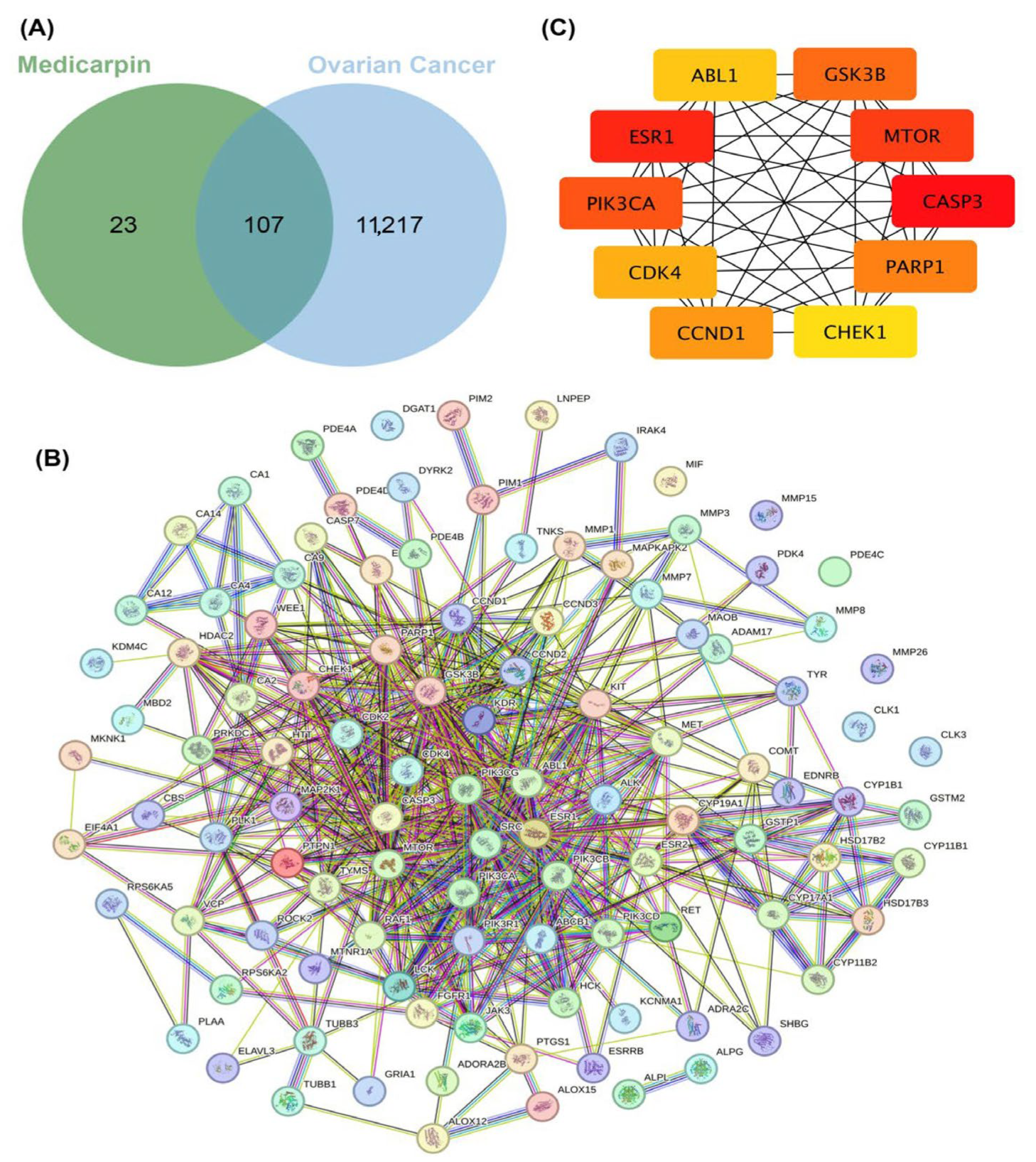

2.3. Identification of Potential Therapeutic Targets and Network Construction of Medicarpin in Ovarian Cancer

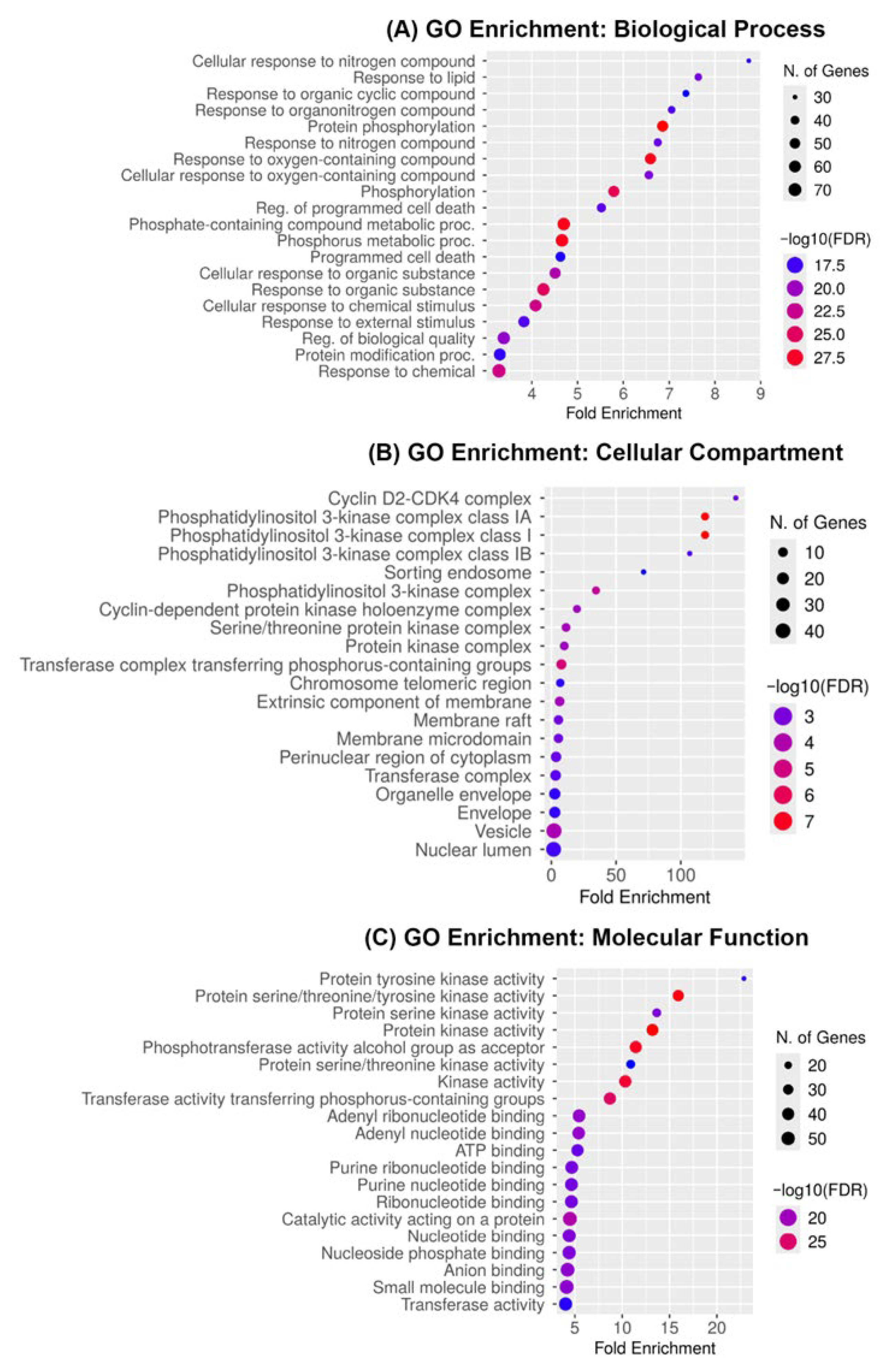

2.4. Gene Ontology Enrichment Reveals Kinase-Mediated and Apoptotic Pathways as Core Mechanisms of Medicarpin Action in Ovarian Cancer

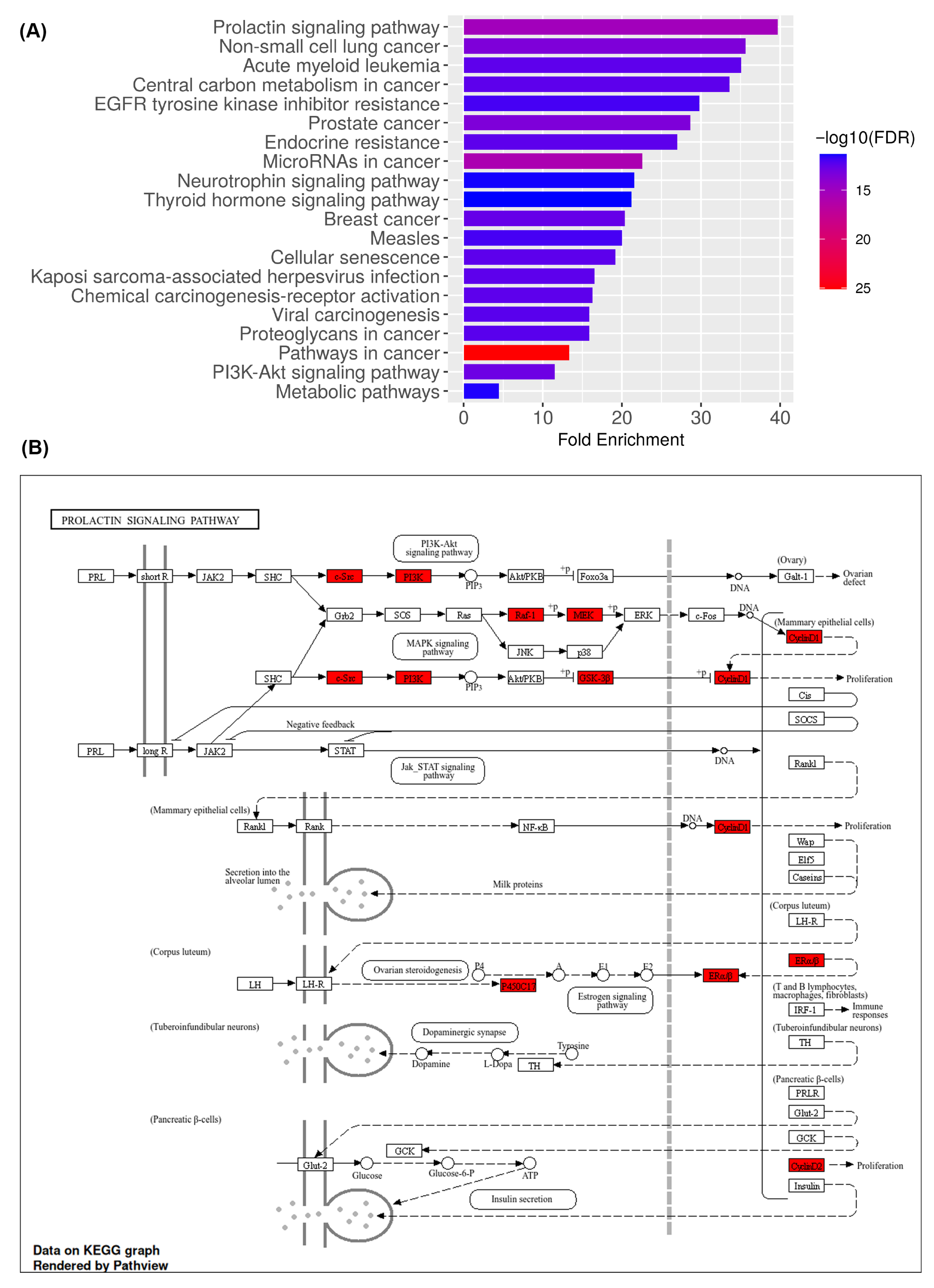

2.5. KEGG Pathway Enrichment and Functional Mapping Identify PI3K-Akt and Prolactin Signaling as Central Mechanisms of Medicarpin Action in Ovarian Cancer

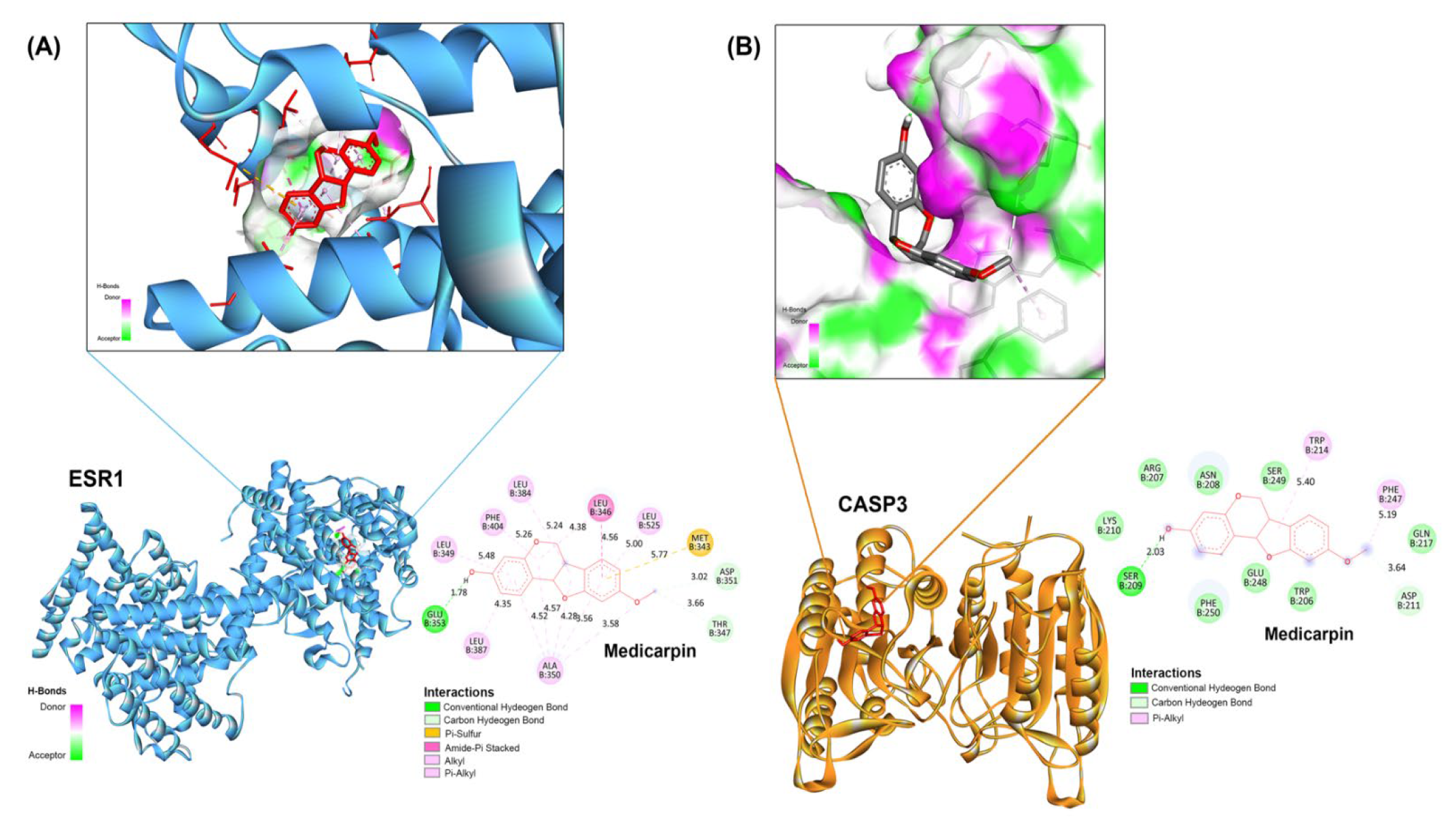

2.6. Validation of Principal Targets Using Molecular Docking

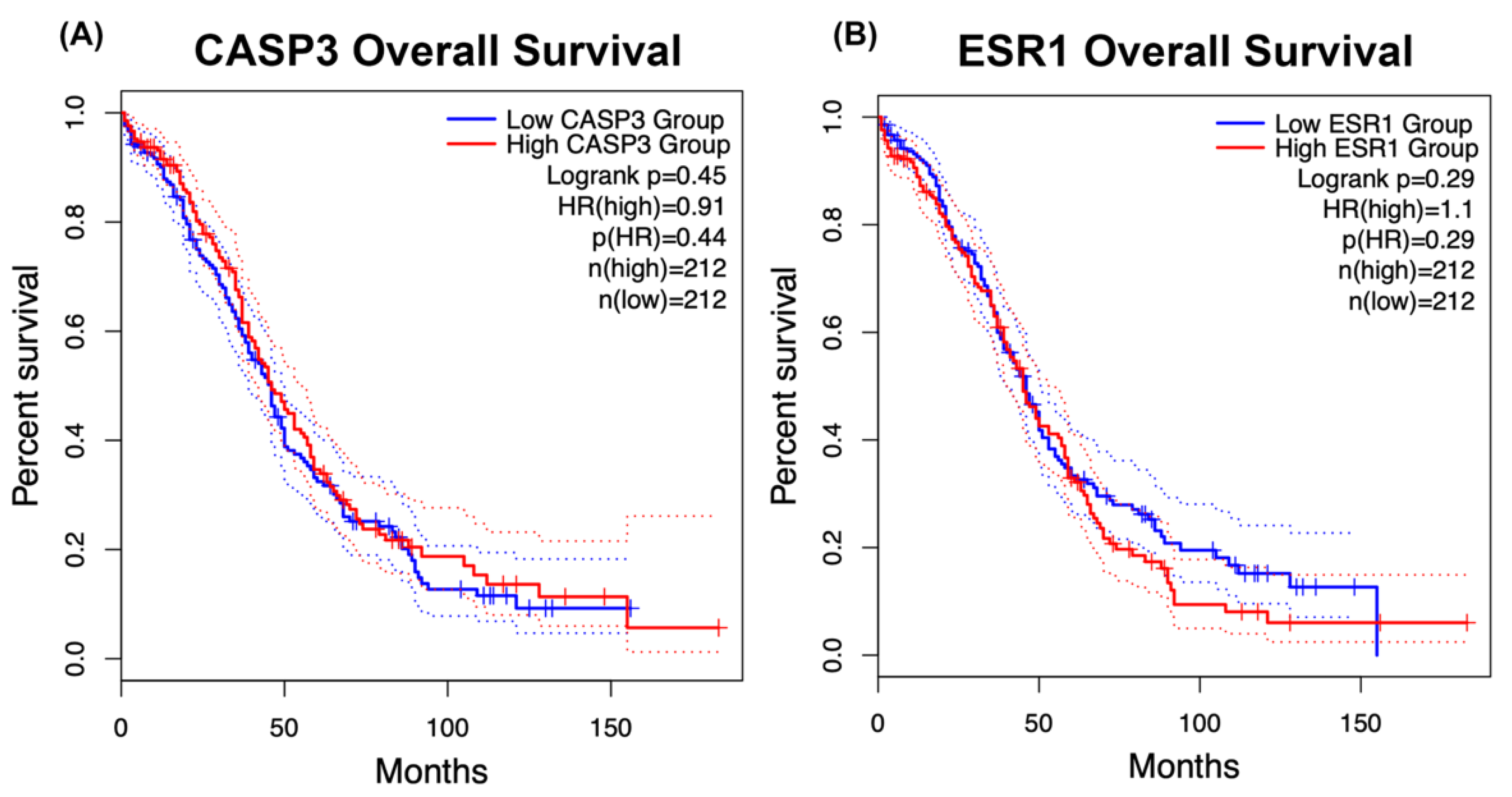

2.7. Prognostic Importance of CASP3 and ESR1 Expression in Ovarian Cancer

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemoinformatics, Drug Likeness, and ADME Predictions

4.2. Prediction of Target Proteins

4.3. Potential Targets Associated with Ovarian Cancer

4.4. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Construction of the Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

4.6. Molecular Docking Studies Involving Medicarpin and Hub Genes

4.7. Survival Analysis of CASP3 and ESR1 Expression in Ovarian Cancer Patients

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| AhR | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| AMPAR | α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate Receptor |

| ATAD5 | ATPase Family AAA Domain-Containing Protein 5 |

| BP | Biological Process |

| CASP3 | Caspase-3 |

| CCND1 | Cyclin D1 |

| CDK | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase |

| CDK2 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2 |

| CDK4 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4 |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| Egan | Egan’s drug-likeness rule |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| ER-α | Estrogen Receptor Alpha |

| ER-LBD | Estrogen Receptor Ligand-Binding Domain |

| ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GABAR | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor |

| GEPIA2 | Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, version 2 |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSK3B | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta |

| HSE | Heat Shock Factor Response Element |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase–Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LD50 | Lethal Dose, 50% |

| LOAEL | Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| OC | Ovarian Cancer |

| PAINS | Pan-Assay Interference Compounds |

| PARP1 | Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 |

| PBK | PDZ-Binding Kinase |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| PKCSM | Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Prediction Model |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| ProTox-III | Prediction of Toxicity, version 3 |

| PXR | Pregnane X Receptor |

| RYR | Ryanodine Receptor |

| SEA | Similarity Ensemble Approach |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area |

| TRAIL | TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

References

- Lheureux, S.; Braunstein, M.; Oza, A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lheureux, S.; Gourley, C.; Vergote, I.; Oza, A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet 2019, 393, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, A.; Harter, P.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; Miller, R.E.; Pothuri, B.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Tan, D.S.P.; Bellet, E.; Oaknin, A.; et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patch, A.M.; Christie, E.L.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Garsed, D.W.; George, J.; Fereday, S.; Nones, K.; Cowin, P.; Alsop, K.; Bailey, P.J.; et al. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature 2015, 521, 489–494, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14410. Erratum in Nature 2015, 527, 398. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15716.. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Zhan, F.; Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Xu, J. The latest advances with natural products in drug discovery and opportunities for the future: A 2025 update. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2025, 20, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Dai, L.; Cao, X.; Ma, Y.; Gulnaz, I.; Miao, X.; Li, X.; Yang, X. Natural products in antiparasitic drug discovery: Advances, opportunities and challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 1419–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, M.; Raghuvanshi, A.; Gupta, C.P.; Kureel, J.; Mansoori, M.N.; Shukla, P.; John, A.A.; Singh, K.; Purohit, D.; Awasthi, P.; et al. Medicarpin, a Natural Pterocarpan, Heals Cortical Bone Defect by Activation of Notch and Wnt Canonical Signaling Pathways. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, J.A.; Mansfield, J.W.; Coxon, D.T. Identification of medicarpin as a phytoalexin in the broad bean plant (Vicia faba L.). Nature 1976, 262, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, C.M.; Lu, C.K.; Liou, K.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Tsai, K.C.; Chang, C.L.; Chang, C.C.; Shen, Y.C. Medicarpin isolated from Radix Hedysari ameliorates brain injury in a murine model of cerebral ischemia. J. Food Drug Anal. 2021, 29, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Yan, F.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, T. Medicarpin Protects Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Cells Against Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation-Induced Injury via the PI3K/Akt/FoxO Pathway: A Study of Network Pharmacology Analysis and Experimental Validation. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.; Maurya, R.; Mishra, D.P. Medicarpin, a legume phytoalexin, sensitizes myeloid leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of DR5 and activation of the ROS-JNK-CHOP pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wu, H.Y. Network pharmacology- and molecular docking-based exploration of the molecular mechanism underlying Jianpi Yiwei Recipe treatment of gastric cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 2988–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Bai, H.; Ning, K. Network Pharmacology Databases for Traditional Chinese Medicine: Review and Assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.B.; Li, Q.Y.; Chen, Q.L.; Su, S.B. Network pharmacology: A new approach for Chinese herbal medicine research. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 621423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, D.; Bertazzo, M.; Recanatini, M.; Masetti, M.; Cavalli, A. Dynamic Docking: A Paradigm Shift in Computational Drug Discovery. Molecules 2017, 22, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.A. The rapid evolution of PARP inhibitor therapy for advanced ovarian cancer: Lessons being learned and new questions emerging from phase 3 trial long-term outcome data. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 167, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Y. Suppression of apoptosis in osteocytes, the potential way of natural medicine in the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğin, A.K.; Donmez, H.; Hitit, M.; Seven, S.; Eser, N.; Kurar, E.; Seven, M. The effect of medicarpin on PTEN/AKT signal pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022, 18, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, P.; Akula, S.M.; Abrams, S.L.; Steelman, L.S.; Martelli, A.M.; Cocco, L.; Ratti, S.; Candido, S.; Libra, M.; Montalto, G.; et al. Targeting GSK3 and Associated Signaling Pathways Involved in Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Nomoto, D.; Okadome, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Baba, H. Tumor immune microenvironment and immune checkpoint inhibitors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 3132–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.W.; Roggeveen, C.M.; Sun, J.; Kunhiraman, H.; McSwain, L.F.; Juraschka, K.; Kumar, S.A.; Saulnier, O.; Taylor, M.D.; Schniederjan, M.; et al. The LIN28B-let-7-PBK pathway is essential for group 3 medulloblastoma tumor growth and survival. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 1784–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.X.; He, M.H.; Dai, Z.H.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.G.; Li, X.C.; Jiang, B.B.; Ke, Z.F.; Su, T.H.; Peng, Z.W.; et al. Genomic and transcriptional heterogeneity of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 990–997, https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz103. Erratum in Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2025.03.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ying, L.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, R.; Liang, Y.; Yu, C.; Yang, Z. Medicarpin suppresses proliferation and triggeres apoptosis by upregulation of BID, BAX, CASP3, CASP8, and CYCS in glioblastoma. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 102, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafna, D.; Ban, F.; Rennie, P.S.; Singh, K.; Cherkasov, A. Computer-Aided Ligand Discovery for Estrogen Receptor Alpha. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Peng, J.; Liu, W.; He, X.; Cui, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, H. Elevated cleaved caspase-3 is associated with shortened overall survival in several cancer types. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 5057–5070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, S.; Jiang, L.; Tan, Z.; Wang, J. A Systematic Pan-Cancer Analysis of CASP3 as a Potential Target for Immunotherapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 776808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darb-Esfahani, S.; Wirtz, R.M.; Sinn, B.V.; Budczies, J.; Noske, A.; Weichert, W.; Faggad, A.; Scharff, S.; Sehouli, J.; Oskay-Ozcelik, G.; et al. Estrogen receptor 1 mRNA is a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma: Determination by kinetic PCR in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2009, 16, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.; Tsang, Y.T.M.; Gershenson, D.M.; Wong, K.K. The prognostic value of MEK pathway-associated estrogen receptor signaling activity for female cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Nagel, C.I.; Haight, P.J. Targeted Therapies in Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancers. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W. Balance Cell Apoptosis and Pyroptosis of Caspase-3-Activating Chemotherapy for Better Antitumor Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimento, A.; De Luca, A.; Avena, P.; De Amicis, F.; Casaburi, I.; Sirianni, R.; Pezzi, V. Estrogen Receptors-Mediated Apoptosis in Hormone-Dependent Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.M.; Jang, H.J.; Kang, M.G.; Mun, S.K.; Park, D.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, M.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Yee, S.T.; Kim, H. Medicarpin and Homopterocarpin Isolated from Canavalia lineata as Potent and Competitive Reversible Inhibitors of Human Monoamine Oxidase-B. Molecules 2022, 28, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.A.; Tinker, A.V. PARP Inhibitors and the Evolving Landscape of Ovarian Cancer Management: A Review. BioDrugs 2019, 33, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.M.; Krivak, T.C.; Kabil, N.; Munley, J.; Moore, K.N. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, N.; Christie, E.L.; Ardasheva, A.; Kwok, C.H.; Demchenko, N.; Low, C.; Tralau-Stewart, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Cunnea, P. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in epithelial ovarian cancer, therapeutic treatment options for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limanaqi, F.; Biagioni, F.; Mastroiacovo, F.; Polzella, M.; Lazzeri, G.; Fornai, F. Merging the Multi-Target Effects of Phytochemicals in Neurodegeneration: From Oxidative Stress to Protein Aggregation and Inflammation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Wen, G.; Dong, M. Development of 99mTc-Hynic-Adh-1 Molecular Probe Specifically Targeting N-Cadherin and Its Preliminary Experimental Study in Monitoring Drug Resistance of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerifar, S.; Norouzi, M.; Ghandi, M. A tool for feature extraction from biological sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.Y.; Wu, J.R.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y.B.; Shang, D.D.; Liu, S.; Fan, G.W.; Cui, Y.L. Integration of transcriptomics and system pharmacology to reveal the therapeutic mechanism underlying Qingfei Xiaoyan Wan to treat allergic asthma. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Tian, L.; Li, Q.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of the Physicochemical Properties of Acaricides Based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five. J. Comput. Biol. 2020, 27, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimmer, E.C.; Huntley, R.P.; Alam-Faruque, Y.; Sawford, T.; O’Donovan, C.; Martin, M.J.; Bely, B.; Browne, P.; Mun Chan, W.; Eberhardt, R.; et al. The UniProt-GO Annotation database in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D565–D570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, M.; Dalah, I.; Alexander, J.; Rosen, N.; Iny Stein, T.; Shmoish, M.; Nativ, N.; Bahir, I.; Doniger, T.; Krug, H.; et al. GeneCards Version 3: The human gene integrator. Database 2010, 2010, baq020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardou, P.; Mariette, J.; Escudié, F.; Djemiel, C.; Klopp, C. jvenn: An interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Nastou, K.; Koutrouli, M.; Kirsch, R.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Hu, D.; Peluso, M.E.; Huang, Q.; Fang, T.; et al. The STRING database in 2025: Protein networks with directionality of regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D730–D737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otasek, D.; Morris, J.H.; Bouças, J.; Pico, A.R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: Empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wu, H.H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko, M.T.; Lin, C.Y. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, B.; Wang, H.; Khalaf, H.K.S.; Blay, V.; Houston, D.R. AutoDock-SS: AutoDock for Multiconformational Ligand-Based Virtual Screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3779–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Protein Name | PDB | Compound and Positive Control | Binding Energies (kcal/mol) | Inhibition Constant (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CASP3 | 7RN9 | Medicarpin | −6.13 | 32.24 uM |

| ASA | −0.19 | 382.65 mM | |||

| 2 | ESR1 | 6VPF | Medicarpin | −7.68 | 2.37 uM |

| 53Q | −3.64 | 2.14 mM | |||

| 3 | CDK4 | 6P8F | Medicarpin | −7.87 | 1.57 uM |

| PTR | −7.66 | 2.43 uM | |||

| 4 | CCND1 | 6P8F | Medicarpin | −7.91 | 1.6 uM |

| PTR | −7.68 | 2.33 uM | |||

| 5 | MTOR | 5OQ4 | Medicarpin | −7.92 | 1.57 uM |

| A3W | −7.59 | 2.73 uM | |||

| 6 | PIK3CA | 5XGH | Medicarpin | −6.39 | 20.57 uM |

| 84U | −7.71 | 2.22 uM | |||

| 7 | PARP1 | 7KK4 | Medicarpin | −7.43 | 3.61 uM |

| 09L | −11.52 | 3.62 nM | |||

| 8 | GSK3B | 4ACC | Medicarpin | −6.8 | 10.45 uM |

| 7YG | −7.2 | 5.26 uM | |||

| 9 | CHEK1 | 2HXL | Medicarpin | −7.03 | 7.06 uM |

| 422 | −12.07 | 1.43 nM | |||

| 10 | ABL1 | 4WA9 | Medicarpin | −7.91 | 1.6 uM |

| AXI | −10.13 | 37.54 nM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rattanapan, Y.; Sitthirak, S.; Tedasen, A.; Duangchan, T.; Dokduang, H.; Pattaranggoon, N.C.; Saisuwan, K.; Chareonsirisuthigul, T. Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Identify Medicarpin as a Potent CASP3 and ESR1 Binder Driving Apoptotic and Hormone-Dependent Anticancer Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010174

Rattanapan Y, Sitthirak S, Tedasen A, Duangchan T, Dokduang H, Pattaranggoon NC, Saisuwan K, Chareonsirisuthigul T. Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Identify Medicarpin as a Potent CASP3 and ESR1 Binder Driving Apoptotic and Hormone-Dependent Anticancer Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010174

Chicago/Turabian StyleRattanapan, Yanisa, Sirinya Sitthirak, Aman Tedasen, Thitinat Duangchan, Hasaya Dokduang, Nawanwat C. Pattaranggoon, Krittamate Saisuwan, and Takol Chareonsirisuthigul. 2026. "Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Identify Medicarpin as a Potent CASP3 and ESR1 Binder Driving Apoptotic and Hormone-Dependent Anticancer Activity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010174

APA StyleRattanapan, Y., Sitthirak, S., Tedasen, A., Duangchan, T., Dokduang, H., Pattaranggoon, N. C., Saisuwan, K., & Chareonsirisuthigul, T. (2026). Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Identify Medicarpin as a Potent CASP3 and ESR1 Binder Driving Apoptotic and Hormone-Dependent Anticancer Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010174