Update and Reassessment of Data on the Role of Osteocalcin in Bone Properties and Glucose Homeostasis in OC-/- Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A.

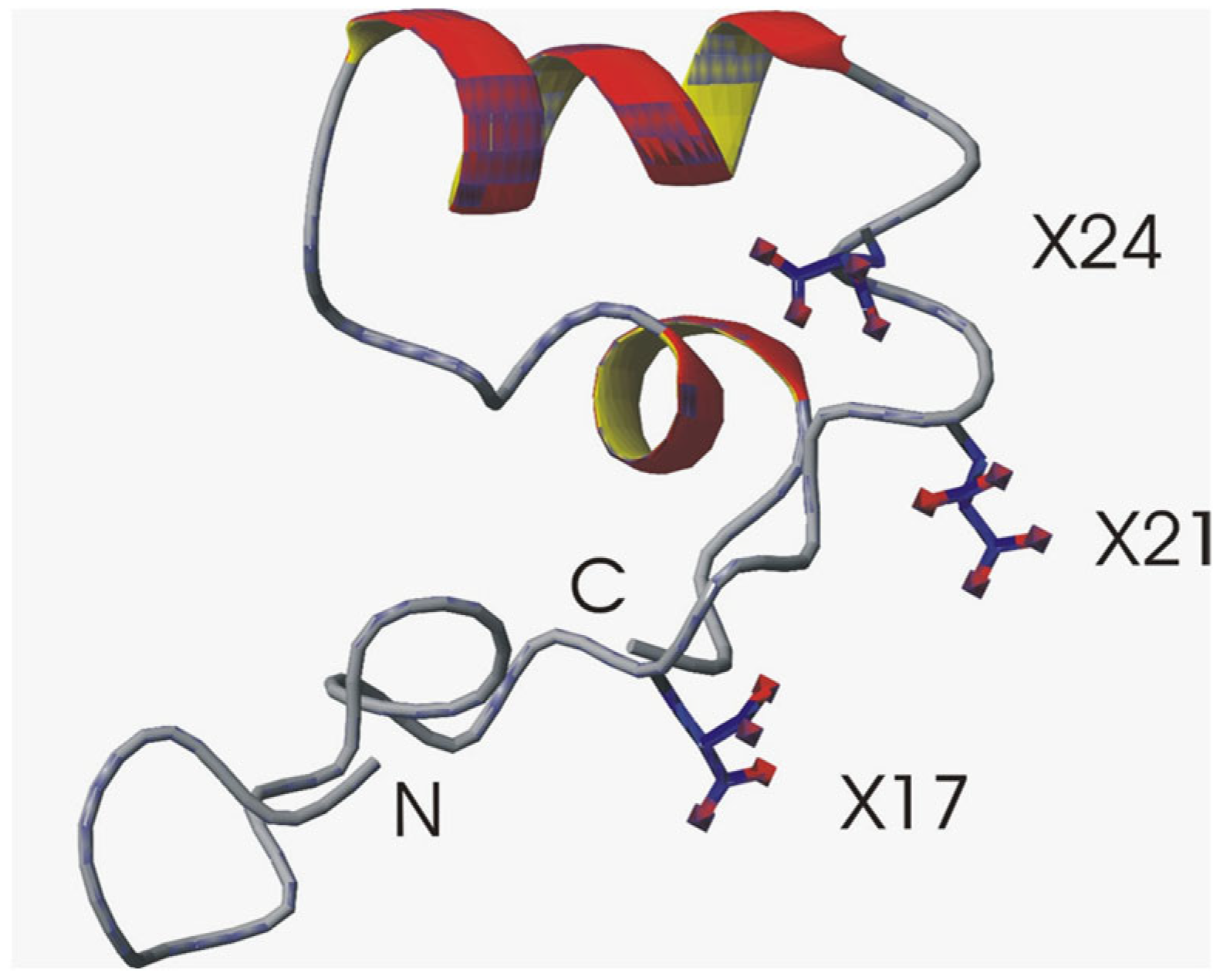

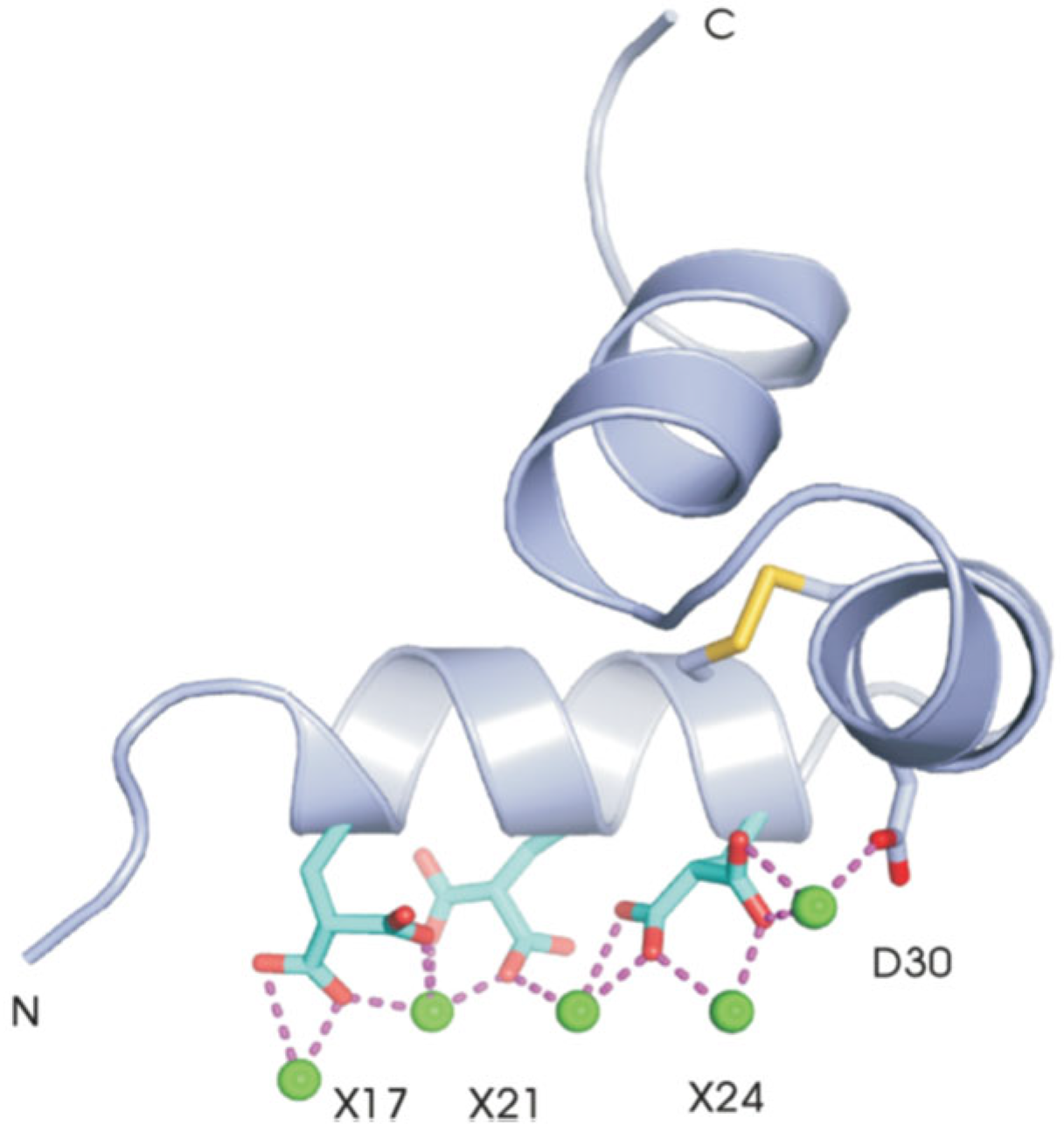

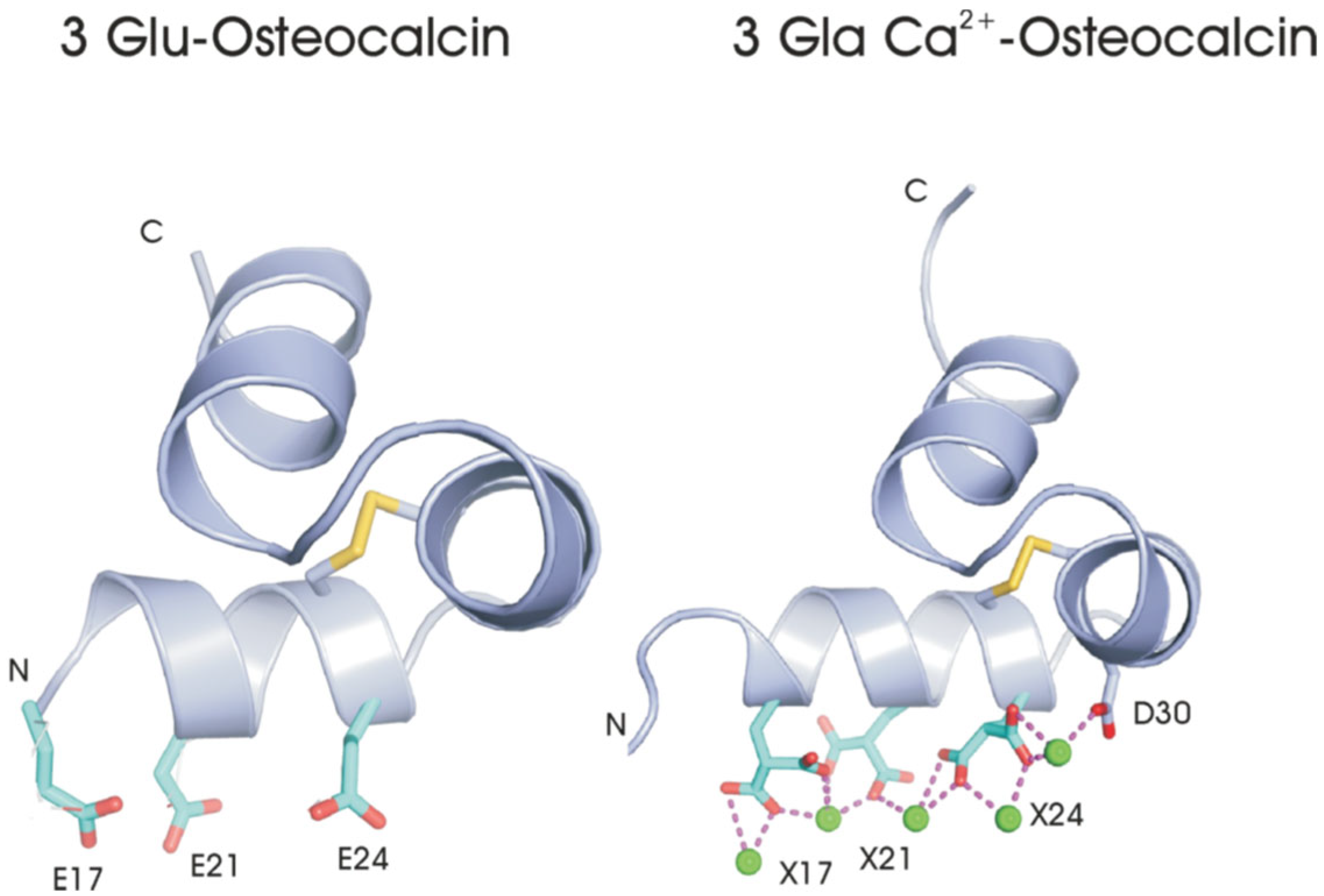

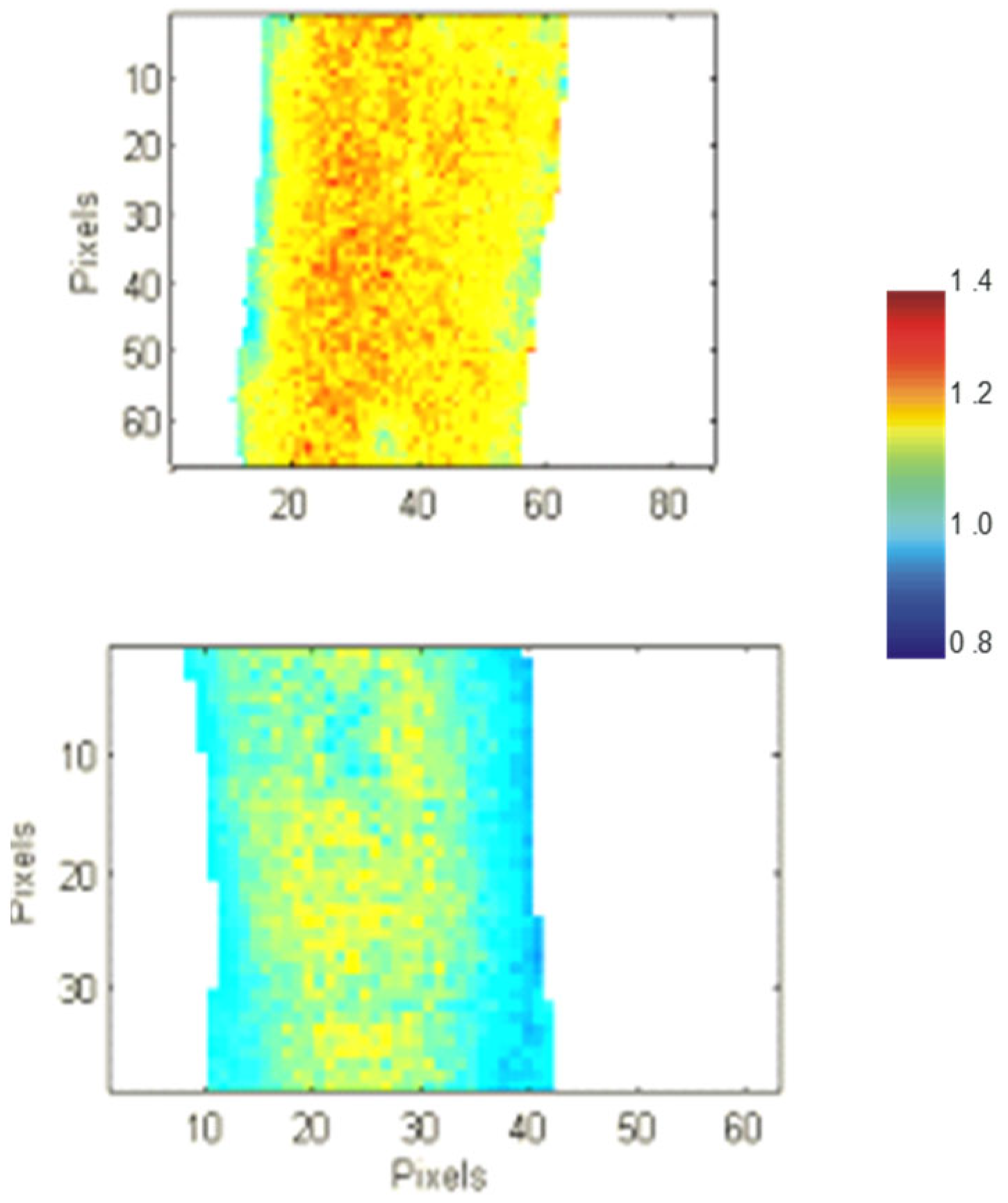

- Structural studies

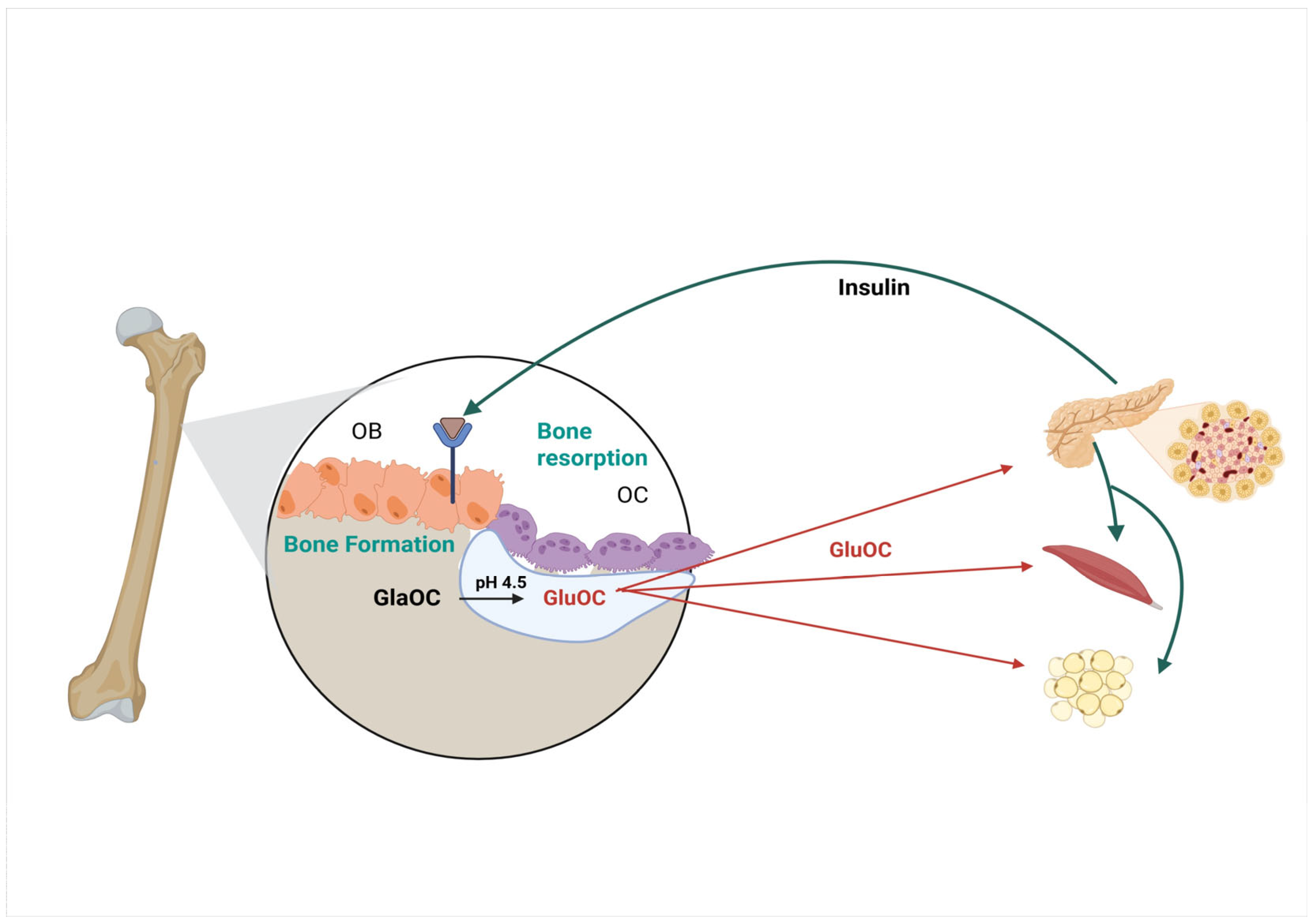

2. OC-/- Mice

3. Effect of Osteocalcin on Bone Quality

4. Bone Biomechanical Measurements

5. The Role of Osteocalcin in Diabetes and Glucose Metabolism

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hauschka, P.V.; Lian, J.B.; Gallop, P.M. Direct identification of the calcium binding amino acid, g-carboxyglutamate in mineralized tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 3925–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.A.; Otsuka, A.S.; Poser, J.W.; Kristaponis, J.; Raman, N. Characterization of a g-carboxyglutamic acid containing protein from bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriishi, T.; Ozasa, R.; Ishimoto, T.; Nakano, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Liu, W.; Fukuyama, R.; Wang, Y.; Komori, H.; et al. Osteocalcin is necessary for the alignment of apatite crystallites, but not glucose metabolism, testosterone synthesis, or muscle mass. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diegel, C.R.; Hann, S.; Ayturk, U.M.; Hu, J.C.W.; Lim, K.E.; Droscha, C.J.; Madaj, Z.B.; Foxa, G.E.; Izaguirre, I.; Transgenics Core, V.V.A.; et al. An osteocalcin-deficient mouse strain without endocrine abnormalities. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducy, P.; Desbois, C.; Boyce, B.; Pinero, G.; Story, B.; Dunstan, C.; Smith, E.; Bonadio, J.; Goldstein, S.; Gundberg, C.; et al. Increased bone formation in osteocalcin-deficient mice. Nature 1996, 382, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, M.; Wei, J.; Yoshizawa, T.; Del Fattore, A.; DePinho, R.A.; Teti, A.; Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.K.; Sowa, H.; Hinoi, E.; Ferron, M.; Ahn, J.D.; Confavreux, C.; Dacquin, R.; Mee, P.J.; McKee, M.D.; Jung, D.Y. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 2007, 130, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paracha, N.; Mastrokostas, P.; Kello, E.; Gedailovich, Y.; Segall, D.; Rizzo, A.; Mitelberg, L.; Hassan, N.; Dowd, T.L. Osteocalcin improves glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and secretion in older male mice. Bone 2024, 182, 117048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poundarik, A.A.; Boskey, A.; Gundberg, C.; Vashishth, D. Biomolecular regulation, composition and nanoarchitecture of bone mineral. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.; Karsenty, G.; Gundberg, C.; Vashishth, D. Osteocalcin and osteopontin influence bone morphology and mechanical properties. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1409, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkner, K.L. The vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2005, 25, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauschka, P.V.; Carr, S.A. Calcium-dependent. alpha.-helical structure in osteocalcin. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 2538–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, T.; Rosen, J.; Li, L.; Gundberg, C. The three-dimensional structure of bovine calcium ion-bound osteocalcin using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 7769–7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, Q.Q.; Sicheri, F.; Howard, A.J.; Yang, D.S.C. Bone recognition mechanism of porcine osteocalcin from crystal structure. Nature 2003, 425, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, G.; Morel, G.; Lian, J.B.; Anthoine-Terrier, C.; Dubois, P.M.; Meunier, P.J. Localization of endogenous osteocalcin in neonatal rat bone and its absence in articular cartilage: Effect of warfarin treatment. Virchows Archiv. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1990, 417, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschka, P.V.; Lian, J.B.; Cole, D.E.C.; Gundberg, C.M. Osteocalcin and Matrix Gla proteins: Vitamin K-Dependent Proteins in Bone. Physiol. Rev. 1989, 69, 990–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschka, P.V.; Reid, R.M. Timed appearance of a calcium-binding protein containing gamma-carboxyglutamic acid in developing chick bone. Dev. Biol. 1978, 65, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.D.; Farach-Carson, M.C.; Butler, W.T.; Hauschka, P.V.; Nanci, A. Ultrastructural immunolocalization of noncollagenous, (osteopontin and osteocalcin) and plasma (albumin and alpha 2 HS-glycoprotein) proteins in rat bone. J. Bone Min. Res. 1993, 8, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, P.A.; Lothringer, J.W.; Baukol, S.A.; Reddi, A.H. Developmental appearance of the vitamin K-dependent protein of bone during calcification. Analysis of mineralizing tissues in human, calf, and rat. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 3781–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashkevich, V.N.; Almo, S.C.; Dowd, T.L. X-ray crystal structure of bovine 3 Glu-osteocalcin. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 8387–8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeste, A.; Rosen, V.; Buecker, J.; Kriz, R.; Wang, E.; Wozney, J. Isolation of the human gene for bone gla protein utilizing mouse and rat cDNA clones. EMBO J. 1986, 5, 1885–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Oberdorf, A.; Montecino, M.; Tanhauser, S.M.; Lian, J.B.; Stein, G.S.; Laipis, P.J.; Stein, J.L. Multiple copies of the bone-specific osteocalcin gene in mouse and rat. Endocrinology 1993, 133, 3050–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, C.; Hogue, D.A.; Karsenty, G. The mouse osteocalcin gene cluster contains three genes with two separate spatial and temporal patterns of expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagutelli, X. Effect of the genetic background on the phenotype of mouse mutations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000, 11, S101–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezovska, O.; Yildirim, G.; Budell, W.C.; Yagerman, S.; Pidhaynyy, B.; Bastien, C.; van der Meulen, M.C.H.; Dowd, T.L. Osteocalcin affects bone mineral and mechanical properties in female mice. Bone 2019, 128, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poundarik, A.A.; Diab, T.; Sroga, G.E.; Ural, A.; Boskey, A.L.; Gundberg, C.M.; Vashishth, D. Dilatational band formation in bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19178–19183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducy, P. Bone regulation of insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa Pinto Junior, D.; Canal Delgado, I.; Yang, H.; Clemenceau, A.; Corvelo, A.; Narzisi, G.; Musunuri, R.; Meyer Berger, J.; Hendricks, L.E.; Tokumura, K. Osteocalcin of maternal and embryonic origins synergize to establish homeostasis in offspring. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.K.; Hauschka, P.V.; Poole, A.R.; Rosenberg, L.C.; Goldberg, H.A. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochem. J. 1996, 317, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Tassinari, M.; Glowacki, J. Resorption of implanted bone prepared from normal and warfarin-treated rats. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggett, W.H.; Lian, J.B.; Greenberger, J.S.; Glowacki, J. Osteocalcin promotes differentiation of osteoclast progenitors from murine long-term bone marrow cultures. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 55, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romberg, R.W.; Werness, P.G.; Riggs, B.L.; Mann, K.G. Inhibition of hydroxyapatite-crystal growth by bone-specific and other calcium-binding proteins. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Liu, J.; Hoff, S.E.; Zhu, C.; Heinz, H. Osteocalcin: Promoter or Inhibitor of Hydroxyapatite Growth? Langmuir 2024, 40, 1747–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Grüner, D.; Worch, H.; Pompe, W.; Lichte, H.; El Khassawna, T.; Heiss, C.; Wenisch, S.; Kniep, R. First evidence of octacalcium phosphate@ osteocalcin nanocomplex as skeletal bone component directing collagen triple–helix nanofibril mineralization. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jacquet, R.; Lowder, E.; Landis, W.J. Refinement of collagen–mineral interaction: A possible role for osteocalcin in apatite crystal nucleation, growth and development. Bone 2015, 71, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, M.; Amano, S. Osteocalcin fragment in bone matrix enhances osteoclast maturation at a late stage of osteoclast differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2004, 22, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, S131–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B. Aging and strength of bone as a structural material. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1993, 53, S34–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskey, A.L.; Gadaleta, S.; Gundberg, C.; Doty, S.B.; Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopic analysis of bones of osteocalcin-deficient mice provides insight into the function of osteocalcin. Bone 1998, 23, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskey, A.L.; Donnelly, E.; Boskey, E.; Spevak, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lappe, J.; Recker, R.R. Examining the relationships between bone tissue composition, compositional heterogeneity, and fragility fracture: A matched case-controlled FTIRI study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R.D.; Folz, C.; Manning, S.P.; Swain, P.M.; Zhao, S.-C.; Eustace, B.; Lappe, M.M.; Spitzer, L.; Zweier, S.; Braunschweiger, K. A mutation in the LDL receptor–related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high–bone-mass trait. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 70, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.P.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Covey, M.A.; Cullen, D.M.; Kimmel, D.B.; Recker, R.R. Genetic variations in bone density, histomorphometry, and strength in mice. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000, 67, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, K.J.; Akkus, O.J.; Majeska, R.J.; Nadeau, J.H. Hierarchical relationship between bone traits and mechanical properties in inbred mice. Mamm. Genome 2003, 14, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, E. Methods for assessing bone quality: A review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 2128–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.H.; van der Meulen, M.C. Whole bone mechanics and bone quality. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, K.J.; Silva, M.J.; Vashishth, D.; Guo, X.E.; van der Meulen, M.C. Establishing biomechanical mechanisms in mouse models: Practical guidelines for systematically evaluating phenotypic changes in the diaphyses of long bones. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriero, A.; Zimmermann, E.A.; Shefelbine, S.J.; Ritchie, R.O. A methodology for the investigation of toughness and crack propagation in mouse bone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 39, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikel, O.; Poundarik, A.A.; Bailey, S.; Vashishth, D. Structural role of osteocalcin and osteopontin in energy dissipation in bone. J. Biomech. 2018, 80, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerramshetty, J.S.; Akkus, O. The associations between mineral crystallinity and the mechanical properties of human cortical bone. Bone 2008, 42, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, P.; Laue, K.; Ferron, M.; Confavreux, C.; Wei, J.; Galán-Díez, M.; Lacampagne, A.; Mitchell, S.J.; Mattison, J.A.; Chen, Y. Osteocalcin signaling in myofibers is necessary and sufficient for optimum adaptation to exercise. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, M.; McKee, M.D.; Levine, R.L.; Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. Intermittent injections of osteocalcin improve glucose metabolism and prevent type 2 diabetes in mice. Bone 2012, 50, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Hanna, T.; Suda, N.; Karsenty, G.; Ducy, P. Osteocalcin Promotes β-Cell Proliferation During Development and Adulthood Through Gprc6a. Diabetes 2014, 63, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, M.; Kapoor, K.; Ye, R.; Nishimoto, S.K.; Smith, J.C.; Baudry, J.; Quarles, L.D. Evidence for osteocalcin binding and activation of GPRC6A in β-cells. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 1866–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelke, J.A.; Hale, J.E.; Suttie, J.; Price, P.A. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylase: Utilization of decarboxylated bone Gla protein and matrix Gla protein as substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1991, 1078, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizokami, A.; Mukai, S.; Gao, J.; Kawakubo-Yasukochi, T.; Otani, T.; Takeuchi, H.; Jimi, E.; Hirata, M. GLP-1 signaling is required for improvement of glucose tolerance by osteocalcin. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 244, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizokami, A.; Yasutake, Y.; Gao, J.; Matsuda, M.; Takahashi, I.; Takeuchi, H.; Hirata, M. Osteocalcin induces release of glucagon-like peptide-1 and thereby stimulates insulin secretion in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizokami, A.; Yasutake, Y.; Higashi, S.; Kawakubo-Yasukochi, T.; Chishaki, S.; Takahashi, I.; Takeuchi, H.; Hirata, M. Oral administration of osteocalcin improves glucose utilization by stimulating glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Bone 2014, 69, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabek, O.M.; Nishimoto, S.K.; Fraga, D.; Tejpal, N.; Ricordi, C.; Gaber, A.O. Osteocalcin effect on human β-cells mass and function. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nisio, A.; Rocca, M.S.; Fadini, G.P.; De Toni, L.; Marcuzzo, G.; Marescotti, M.C.; Sanna, M.; Plebani, M.; Vettor, R.; Avogaro, A. The rs2274911 polymorphism in GPRC 6A gene is associated with insulin resistance in normal weight and obese subjects. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 86, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.C.; Jeong, I.K.; Ahn, K.J.; Chung, H.Y. The uncarboxylated form of osteocalcin is associated with improved glucose tolerance and enhanced β-cell function in middle-aged male subjects. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2009, 25, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindblom, J.M.; Ohlsson, C.; Ljunggren, Ö.; Karlsson, M.K.; Tivesten, Å.; Smith, U.; Mellström, D. Plasma osteocalcin is inversely related to fat mass and plasma glucose in elderly Swedish men. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009, 24, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeap, B.B.; Chubb, S.P.; Flicker, L.; McCaul, K.A.; Ebeling, P.R.; Beilby, J.P.; Norman, P.E. Reduced serum total osteocalcin is associated with metabolic syndrome in older men via waist circumference, hyperglycemia, and triglyceride levels. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 163, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janghorbani, M.; Van Dam, R.M.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.V.; Sellmeyer, D.E.; Ensrud, K.E.; Cauley, J.A.; Tabor, H.K.; Schreiner, P.J.; Jamal, S.A.; Black, D.M.; Cummings, S.R. Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: A prospective study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.V.; Vittinghoff, E.; Bauer, D.C.; Hillier, T.A.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Ensrud, K.E.; Donaldson, M.G.; Cauley, J.A.; Harris, T.B.; Koster, A.; et al. Association of BMD and FRAX score with risk of fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2011, 305, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Karsenty | Karsenty/ Boskey | Dowd | Vashishth | Komori | Williams |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic background | 129/BL6 | 129/BL6 | C57BL/6J | C57BL/6J | C57BL/6N | C57BL/6J/C3H |

| Age | 6 mos. | 6 mos. 9 mos. | 6 mos. | 6 mos. | 6 or 9 mos. | N/A * |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female | Male | M and F |  |

| Cortical thickness | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ | |||

| Trabecular bone | ↑ | ↑ | ND | ↔ | ||

| Bone formation | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ||

| Bone resorption | ↔ | ↔ | ND | ↔ | ||

| Carbonate/P | ↔ | ↑ | ND | Not comparable | ||

| Labile CO32− | ↑ | ND | ||||

| B-CO32− | ↑ | ND | ||||

| Acid phosphate | ↑ | ↑ | ND | Not comparable | ||

| Mineral/matrix | ↔ | ↓ | ND | Not comparable | ||

| Crystal size | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Not comparable | ||

| Crystal thickness | ↓ | |||||

| Crystal alignment | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tommassini, S.; Dowd, T.L. Update and Reassessment of Data on the Role of Osteocalcin in Bone Properties and Glucose Homeostasis in OC-/- Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010170

Tommassini S, Dowd TL. Update and Reassessment of Data on the Role of Osteocalcin in Bone Properties and Glucose Homeostasis in OC-/- Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleTommassini, Steven, and Terry Lynne Dowd. 2026. "Update and Reassessment of Data on the Role of Osteocalcin in Bone Properties and Glucose Homeostasis in OC-/- Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010170

APA StyleTommassini, S., & Dowd, T. L. (2026). Update and Reassessment of Data on the Role of Osteocalcin in Bone Properties and Glucose Homeostasis in OC-/- Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010170