Levels of Cu, Zn, and Se in Maternal and Cord Blood in Normal and Pathological Pregnancies: A Narrative Review

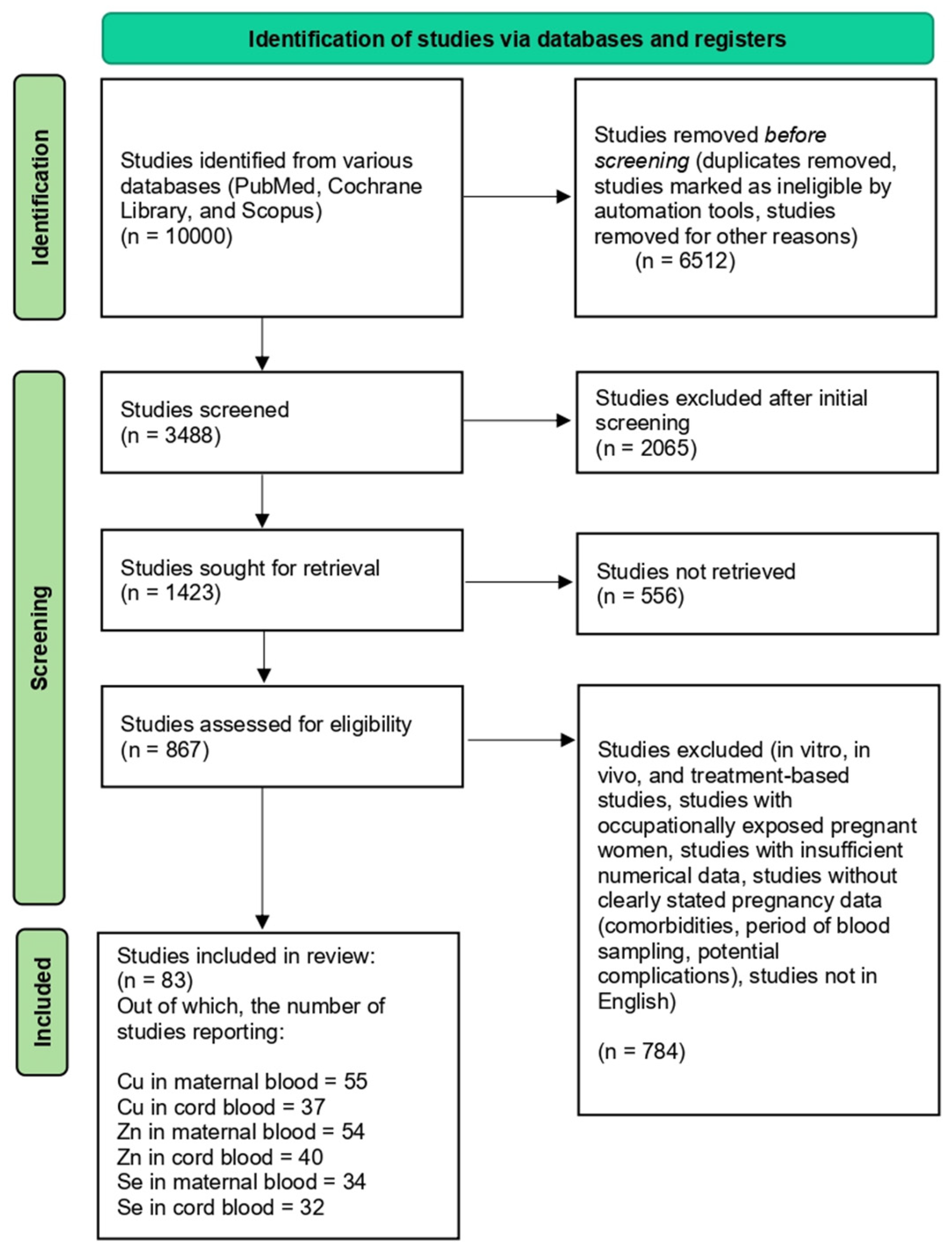

Abstract

1. Introduction

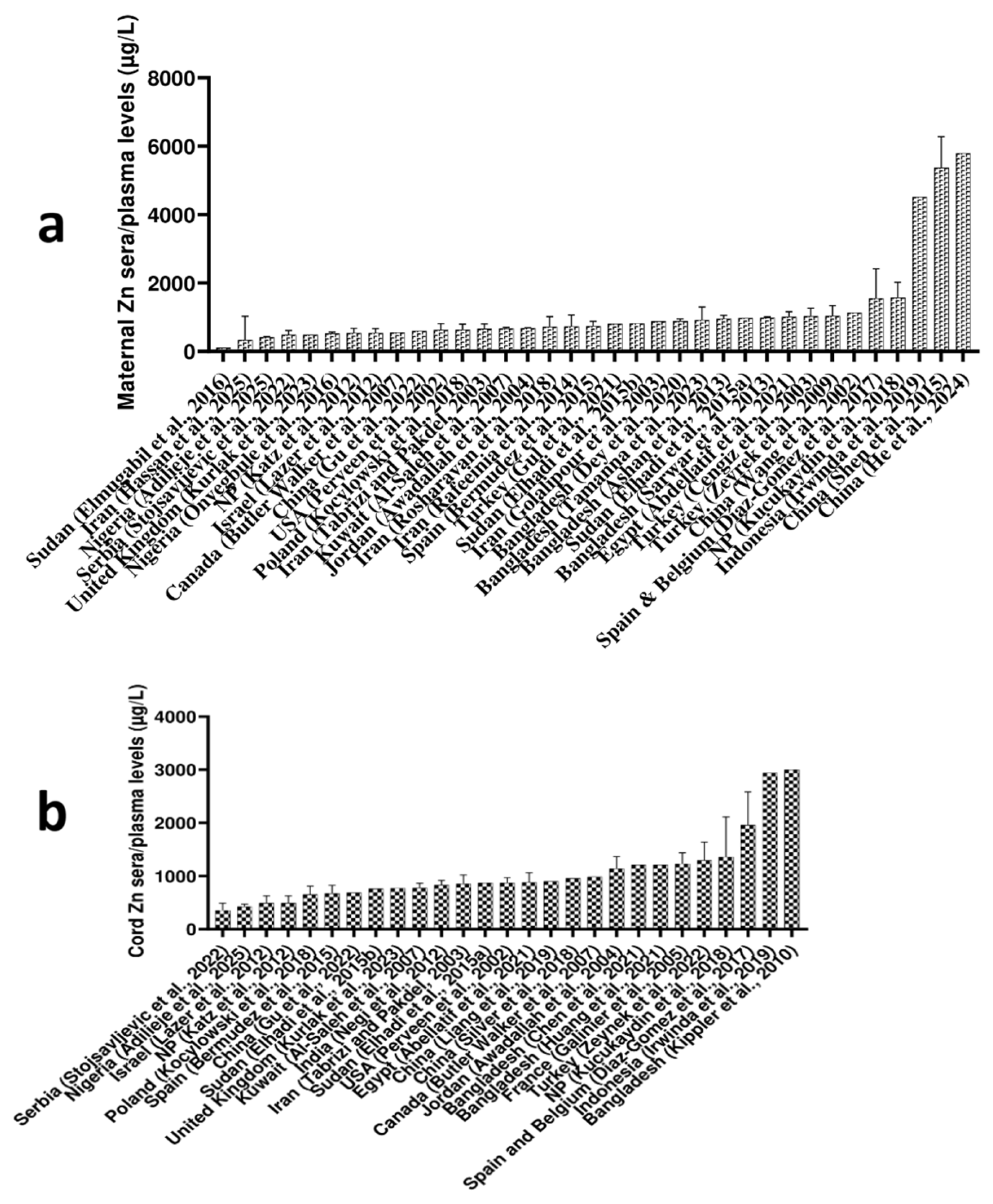

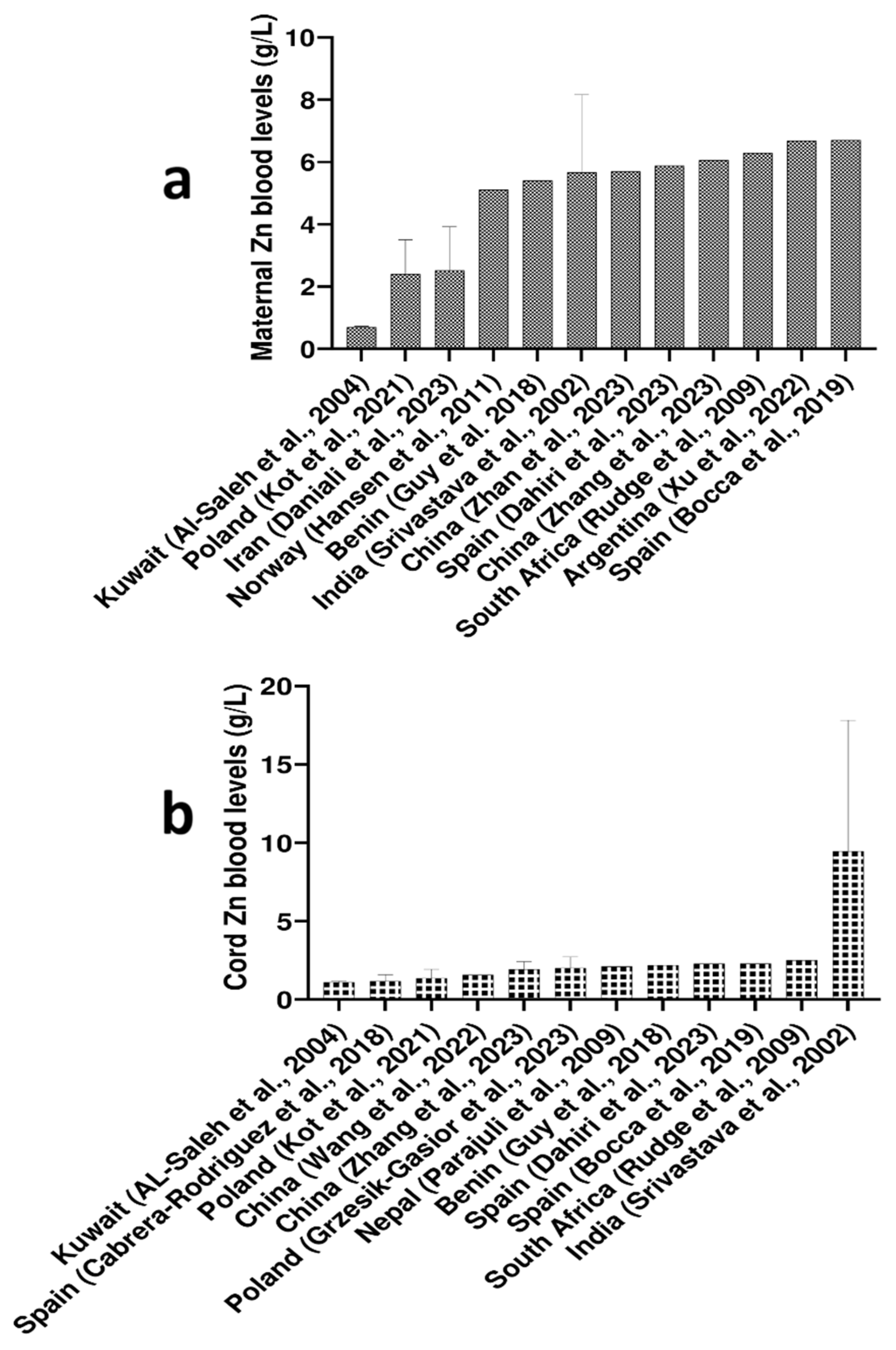

2. Copper, Zn, and Se Circulating Levels in Pregnant Women Around the World

2.1. Maternal Blood Cu, Zn, and Se Levels Worldwide

2.2. Cord Blood Cu, Zn, and Se Levels Worldwide

2.3. Differences in Levels of Cu, Zn, and Se Between Maternal and Cord Blood

2.4. Copper, Zn, and Se Levels Depending on the Trimester of Pregnancy

2.5. Differences in Cu, Zn, and Se Levels Between Arterial and Venous Cord Blood

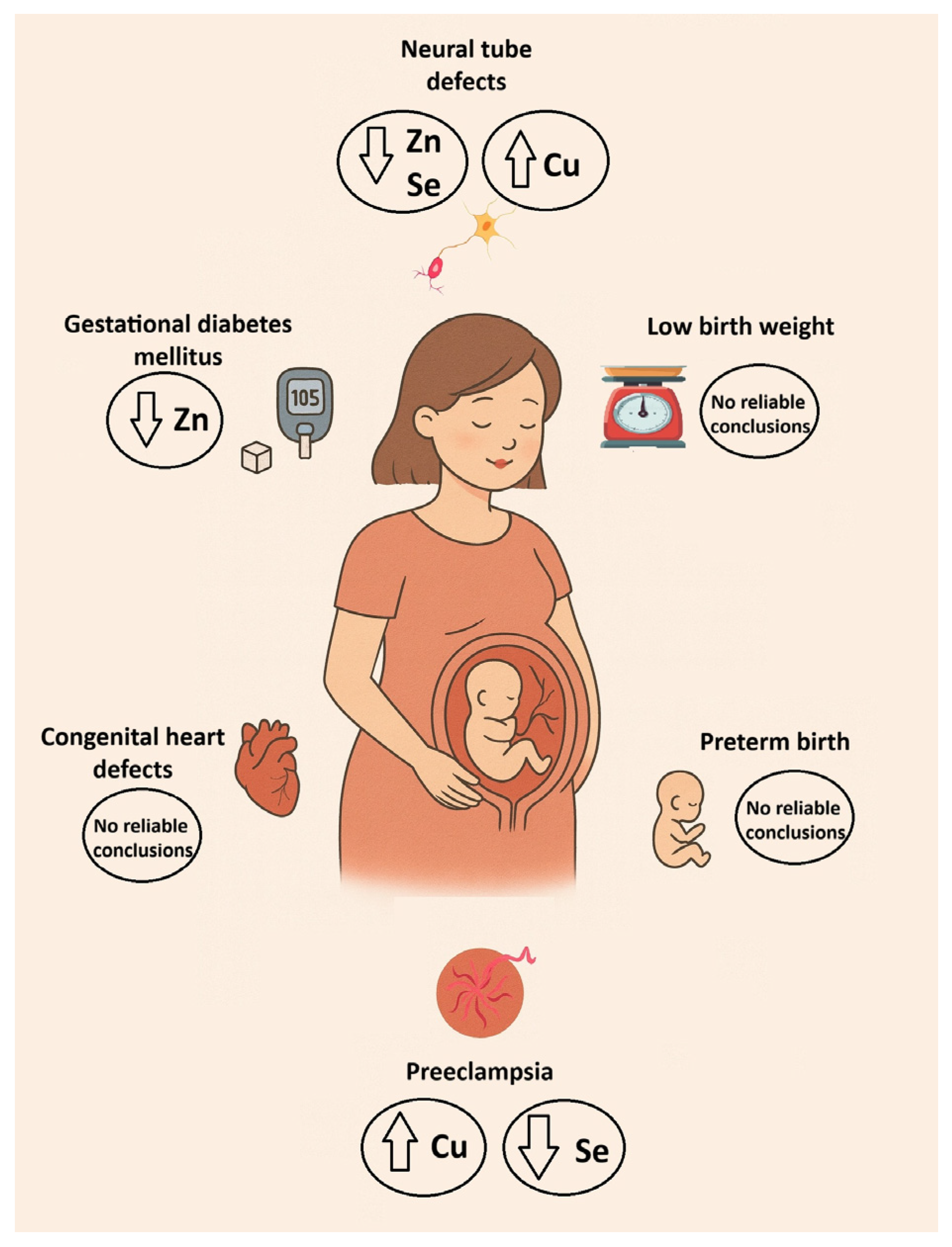

3. Copper, Zn, and Se Levels in Altered Pregnancy

3.1. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se with Birth Weight and Neonatal Anthropometric Parameters

3.2. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se and Preterm Birth

3.3. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se and Preeclampsia

3.4. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

3.5. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se and Neural Tube Defects

3.6. Association Between Cu, Zn, and Se and Congenital Heart Defects

Limitations

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da Silva, J.A.L. Essential Trace Elements in the Human Metabolism. Biology 2024, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaseth, J.O. Toxic and Essential Metals in Human Health and Disease 2021. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehle, P.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Kuhn, K.S. Parenteral Trace Element Provision: Recent Clinical Research and Practical Conclusions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehri, A. Trace Elements in Human Nutrition (II)—An Update. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alonso, M.; Rivas, I.; Miranda, M. Trace Mineral Imbalances in Global Health: Challenges, Biomarkers, and the Role of Serum Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.C. Physiology of Pregnancy and Nutrient Metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1218S–1225S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, M.; Coskun, A.; Bilge, F.; Simsek Imrek, S.; Atli, Y. Serum Reference Levels of Selenium, Zinc and Copper in Healthy Pregnant Women at a Prenatal Screening Program in the Southeastern Mediterranean Region of Turkey. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2010, 24, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhuang, T.; Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, N.; Liu, S. Elevated Non-Essential Metals and the Disordered Metabolism of Essential Metals Are Associated with Abnormal Pregnancy with Spontaneous Abortion. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Selenium. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abregú, F.M.G.; Caniffi, C.; Arranz, C.T.; Tomat, A.L. Impact of Zinc Deficiency During Prenatal and/or Postnatal Life on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, L.; Shariat, M.; Chamari, M.; Chahardoli, R.; Asgarzadeh, L.; Seighali, F. Comparison of Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood Selenium Levels in Low and Normal Birth Weight Neonates. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2015, 9, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeszczak, K.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Kosik-Bogacka, D. The Role of Fe, Zn, and Cu in Pregnancy. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlapati, S.; Venigalla, N.; Mane, S.; Dharmagadda, A.; Sravanthi, K.; Gupta, A. Correlation of Zinc and Copper Levels in Mothers and Cord Blood of Neonates with Prematurity and Intrauterine Growth Pattern. Cureus 2024, 16, e63674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalnaya, M.G.; Tinkov, A.A.; Lobanova, Y.N.; Chang, J.-S.; Skalny, A.V. Serum Levels of Copper, Iron, and Manganese in Women with Pregnancy, Miscarriage, and Primary Infertility. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 56, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Hu, C.; Zheng, Y. Maternal Serum Zinc Level Is Associated with Risk of Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 968045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinggi, U. Selenium: Its Role as Antioxidant in Human Health. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2008, 13, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, A.R.; Dore, G.; Aboud, L.; Makama, M.; Nguyen, P.Y.; Mills, K.; Sanderson, B.; Hastie, R.; Ammerdorffer, A.; Vogel, J.P. The Effect of Selenium Supplementation in Pregnant Women on Maternal, Fetal, and Newborn Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewicka, I.; Kocyłowski, R.; Grzesiak, M.; Gaj, Z.; Oszukowski, P.; Suliburska, J. Selected Trace Elements Concentrations in Pregnancy and Their Possible Role—Literature Review. Ginekol. Pol. 2017, 88, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Ullah, M.S.; Kabir, H.; Rahman, G.K.; Hasnat, A.; Islam, M.S. Comparative Study of Serum Zinc, Copper, Manganese, and Iron in Preeclamptic Pregnant Women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 154, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saleh, E.; Nandakumaran, M.; Al-Rashdan, I.; Al-Harmi, J.; Al-Shammari, M. Maternal–Foetal Status of Copper, Iron, Molybdenum, Selenium and Zinc in Obese Gestational Diabetic Pregnancies. Acta Diabetol. 2007, 44, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyrek, D.; Soran, M.; Cakmak, A.; Kocyigit, A.; Iscan, A. Serum Copper and Zinc Levels in Mothers and Cord Blood of Their Newborn Infants with Neural Tube Defects: A Case-Control Study. Indian Pediatr. 2009, 46, 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Daniali, S.S.; Yazdi, M.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Taheri, E.; Zarean, E.; Goli, P.; Kelishadi, R. Birth Size Outcomes in Relation to Maternal Blood Levels of Some Essential and Toxic Elements. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerstedt, S.; Kippler, M.; Scheynius, A.; Gutzeit, C.; Mie, A.; Alm, J.; Vahter, M. Anthroposophic Lifestyle Influences the Concentration of Metals in Placenta and Cord Blood. Environ. Res. 2015, 136, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyegbule, A.O.; Onah, C.C.; Iheukwumere, B.C.; Udo, J.N.; Atuegbu, C.C.; Nosakhare, N.O. Serum Copper and Zinc Levels in Preeclamptic Nigerian Women. Niger. Med. J. 2016, 57, 182–184, Erratum in Niger. Med. J. 2016, 57, 251. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.188363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I.; Lim, H.S.; Cho, Y.S. Plasma Concentrations of Fe, Cu, Mn, and Cr of Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood During Pregnancy. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2002, 7, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.-J.; Gong, B.; Xu, F.-Y.; Luo, Y. Four Trace Elements in Pregnant Women and Their Relationships with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 4690–4697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Pu, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; He, S.; Ai, S.; Dang, Y. An Exploratory Study on the Association of Multiple Metals in Serum with Preeclampsia. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1336188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwinda, R.; Wibowo, N.; Putri, A.S. The Concentration of Micronutrients and Heavy Metals in Maternal Serum, Placenta, and Cord Blood: A Cross-Sectional Study in Preterm Birth. J. Pregnancy 2019, 2019, 5062365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmugabil, A.; Hamdan, H.Z.; Elsheikh, A.E.; Rayis, D.A.; Adam, I.; Gasim, G.I. Serum Calcium, Magnesium, Zinc and Copper Levels in Sudanese Women with Preeclampsia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.N.; Shamran, S.G.; Albadry, M.A.Z.; Al Fahham, A.A. Evaluation of Serum Levels of Calprotectin, Lactoferrin and Zinc in Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Wiad. Lek. 2025, 78, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilieje, C.M.; Ejezie, C.S.; Obianyido, H.O.; Ugwu, C.C.; Ezeadichie, O.S.; Ejezie, F.E. Assessment of Zinc, Selenium and Vitamin C Status in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood of Intrapartum Women in Enugu Metropolis, Enugu State, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2025, 28, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstead, H. Chapter 61—Zinc. In Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1369–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, B.; Ruggieri, F.; Pino, A.; Rovira, J.; Calamandrei, G.; Martínez, M.Á.; Domingo, J.L.; Alimonti, A.; Schuhmacher, M. Human Biomonitoring to Evaluate Exposure to Toxic and Essential Trace Elements During Pregnancy. Part A: Concentrations in Maternal Blood, Urine and Cord Blood. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Hansen, S.; Sripada, K.; Aarsland, T.; Horvat, M.; Mazej, D.; Alvarez, M.V.; Odland, J.Ø. Maternal Blood Levels of Toxic and Essential Elements and Birth Outcomes in Argentina: The EMASAR Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudge, C.V.; Rollin, H.B.; Nogueira, C.M.A.; Thomassen, Y.; Rudge, M.C.R.; Odland, J.Ø. The Placenta as a Barrier for Toxic and Essential Elements in Paired Maternal and Cord Blood Samples of South African Delivering Women. J. Environ. Monit. 2009, 11, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Shinwari, N.; Mashhour, A.; Mohamed, G.E.D.; Rabah, A. Heavy Metals (Lead, Cadmium and Mercury) in Maternal, Cord Blood and Placenta of Healthy Women. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, R. Influence of Selenium Deficiency on Neural Tube Defects. Asian J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zheng, T.; Cheng, Y.; Holford, T.; Lin, S.; Leaderer, B.; Qiu, J.; Bassig, B.A.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Distributions of Heavy Metals in Maternal and Cord Blood and the Association with Infant Birth Weight in China. J. Reprod. Med. 2015, 60, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stojsavljević, A.; Rovčanin, M.; Miković, Ž.; Perović, M.; Jeremić, A.; Zečević, N.; Manojlović, D. Analysis of Essential, Toxic, Rare Earth, and Noble Elements in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 37375–37383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Moghal, M.M.; Sarwar, M.S.; Anonna, S.N.; Akter, M.; Karmakar, P.; Ahmed, S.; Sattar, M.A.; Islam, S. Low Serum Selenium Concentration Is Associated with Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women from Bangladesh. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2016, 33, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Mehrotra, P.K.; Srivastava, S.P.; Siddiqui, M.K.J. Some Essential Elements in Maternal and Cord Blood in Relation to Birth Weight and Gestational Age of the Baby. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2002, 86, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Abdellatif, M.; Elhawary, I.M.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Youness, E.R.; Abuelhamd, W.A. Cord Levels of Zinc and Copper in Relation to Maternal Serum Levels in Different Gestational Ages. Egypt. Pediatr. Assoc. Gaz. 2021, 69, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlak, L.O.; Scaife, P.J.; Briggs, L.V.; Broughton Pipkin, F.; Gardner, D.S.; Mistry, H.D. Alterations in Antioxidant Micronutrient Concentrations in Placental Tissue, Maternal Blood and Urine and the Fetal Circulation in Pre-eclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, F.M.; Pakdel, F.G. Serum Level of Some Minerals during Three Trimesters of Pregnancy in Iranian Women and Their Newborns: A Longitudinal Study. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 29, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippler, M.; Hoque, A.M.; Raqib, R.; Ohrvik, H.; Ekström, E.C.; Vahter, M. Accumulation of Cadmium in Human Placenta Interacts with the Transport of Micronutrients to the Fetus. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, H.-T.; Hoang, V.H.; Nga, L.T.Q.; Nguyen, V.Q. Effects of Zn Pollution on Soil: Pollution Sources, Impacts and Solutions. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 17, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wei, L.; Huang, H.; Zhang, R.; Su, L.; Rahman, M.; Mostofa, G.; Qamruzzaman, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Assessment of Individual and Mixture Effects of Element Exposure Measured in Umbilical Cord Blood on Birth Weight in Bangladesh. Environ. Res. Commun. 2021, 3, 10500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Su, L.; Rahman, M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Qamruzzaman, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; et al. Cord Serum Elementomics Profiling of 56 Elements Depicts Risk of Preterm Birth: Evidence from a Prospective Birth Cohort in Rural Bangladesh. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, R.; Pande, D.; Karki, K.; Kumar, A.; Khanna, R.S.; Khanna, H.D. Trace Elements and Antioxidant Enzymes Associated with Oxidative Stress in Pre-Eclamptic/Eclamptic Mothers During Fetal Circulation. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 946–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojsavljević, A.; Rovčanin, M.; Jagodić, J.; Miković, Ž.; Jeremić, A.; Perović, M.; Manojlović, D. Evaluation of Maternal Exposure to Multiple Trace Elements and Their Detection in Umbilical Cord Blood. Expo. Health 2021, 13, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, T.; Paz-Tal, O.; Katz, O.; Aricha-Tamir, B.; Sheleg, Y.; Maman, R.; Silberstein, T.; Mazor, M.; Wiznitzer, A.; Sheiner, E. Trace Elements’ Concentrations in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Plasma at Term Gestation: A Comparison Between Active Labor and Elective Cesarean Delivery. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, S.M.; Abu-Elteen, K.H.; Elkarmi, A.Z.; Qaraein, S.H.; Salem, N.M.; Mubarak, M.S. Maternal and Cord Blood Serum Levels of Zinc, Copper, and Iron in Healthy Pregnant Jordanian Women. J. Trace Elem. Exp. Med. 2004, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.B.; Houseman, J.; Seddon, L.; McMullen, E.; Tofflemire, K.; Mills, C.; Corriveau, A.; Weber, J.-P.; LeBlanc, A.; Walker, M.; et al. Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of Mercury, Lead, Cadmium, and Essential Trace Elements in Arctic Canada. Environ. Res. 2006, 100, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Gómez, N.M.; Bissé, E.; Senterre, T.; González-González, N.L.; Domenech, E.; Lindinger, G.; Epting, T.; Barroso, F. Levels of Silicon in Maternal, Cord, and Newborn Serum and Their Relation with Those of Zinc and Copper. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y. The Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Low-Level Cadmium, Lead and Selenium on Birth Outcomes. Chemosphere 2014, 108, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Lagos, F.; Navarro-Alarcon, M.; Terres-Martos, C.; Lopez-Garcia De La Serrana, H.; Pérez-Valero, V.; Lopez-Martinez, M.C. Zinc and Copper Concentrations in Serum from Spanish Women During Pregnancy. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1998, 61, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanska, K.; Hanke, W.; Krol, A.; Gromadzinska, J.; Kuras, R.; Janasik, B.; Wasowicz, W.; Mirabella, F.; Chiarotti, F.; Calamandrei, G. Micronutrients During Pregnancy and Child Psychomotor Development: Opposite Effects of Zinc and Selenium. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Zou, Y.; Qiu, L. Variations in Blood Copper and Possible Mechanisms During Pregnancy. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pi, X.; Yin, S.; Liu, M.; Tian, T.; Jin, L.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Maternal Exposure to Heavy Metals and Risk for Severe Congenital Heart Defects in Offspring. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meram, I.; Bozkurt, A.I.; Ahi, S.; Ozgur, S. Plasma Copper and Zinc Levels in Pregnant Women in Gaziantep, Turkey. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Monia, M.M.; Fethi, B.A.; Wafa, L.B.; Hédi, R. Statut du Zinc et du Cuivre chez la Femme Enceinte et leurs Variations au Cours de la Pré-éclampsie [Status of Zinc and Copper in Pregnant Women and Their Changes During Preeclampsia]. Ann. Biol. Clin. 2012, 70, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thauvin, E.; Fusselier, M.; Arnaud, J.; Faure, H.; Favier, M.; Coudray, C.; Richard, M.-J.; Favier, A. Effects of a Multivitamin Mineral Supplement on Zinc and Copper Status During Pregnancy. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1992, 32, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borella, P.; Szilagyi, A.; Than, G.; Csaba, I.; Giardino, A.; Facchinetti, F. Maternal Plasma Concentrations of Magnesium, Calcium, Zinc and Copper in Normal and Pathological Pregnancies. Sci. Total Environ. 1990, 99, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-S.; Eum, K.-D.; Golam, M.; Quamruzzaman, Q.; Kile, M.L.; Mazumdar, M.; Christiani, D.C. Umbilical Cord Blood Metal Mixtures and Birth Size in Bangladeshi Children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 57006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo Alvarez, S.; Castañón, S.G.; Ruata, M.L.; Aragüés, E.F.; Terraz, P.B.; Irazabal, Y.G.; González, E.G.; Rodríguez, B.G. Updating of Normal Levels of Copper, Zinc and Selenium in Serum of Pregnant Women. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2007, 21, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Piao, J.; Mao, D.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, L.; Yang, X. Reference Values of 14 Serum Trace Elements for Pregnant Chinese Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in the China Nutrition and Health Survey 2010–2012. Nutrients 2017, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagha, U.I.; Ogbodo, S.O.; Nwogu-Ikojo, E.E.; Ibegbu, D.M.; Ejezie, F.E.; Nwagha, T.U.; Dim, C.C. Copper and Selenium Status of Healthy Pregnant Women in Enugu, Southeastern Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2011, 14, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.C.; Ododo, N.A.; Ugwu, E.O.; Enebe, J.T.; Onyegbule, O.A.; Eze, I.O.; Ezem, B.U. Serum Selenium Levels of Pre-Eclamptic and Normal Pregnant Women in Nigeria: A Comparative Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoushabi, F.; Shadan, M.R.; Miri, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Determination of Maternal Serum Zinc, Iron, Calcium and Magnesium During Pregnancy in Pregnant Women and Umbilical Cord Blood and Their Association With Outcome of Pregnancy. Mater. Sociomed. 2016, 28, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.M.; Leung, P.L.; Sun, D.Z.; Zhu, M.G. Hair and Serum Calcium, Iron, Copper, and Zinc Levels During Normal Pregnancy at Three Trimesters. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1999, 69, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, R.; Sun, J.; Yoo, H.; Kim, S.; Cho, Y.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Chung, J.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y. A Prospective Study of Serum Trace Elements in Healthy Korean Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2016, 8, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukaydin, Z.; Kurdoglu, M.; Kurdoglu, Z.; Demir, H.; Yoruk, I.H. Selected Maternal, Fetal and Placental Trace Element and Heavy Metal and Maternal Vitamin Levels in Preterm Deliveries with or without Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurway, J.; Logan, P.; Pak, S. The Development, Structure and Blood Flow within the Umbilical Cord with Particular Reference to the Venous System. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2012, 15, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.P.; Wen, J.; Yang, K.; Zhao, S.L.; Dai, J.; Liang, Z.S.; Cao, Y. Effects of Arterial Blood on the Venous Blood Vessel Wall and Differences in Percentages of Lymphocytes and Neutrophils Between Arterial and Venous Blood. Medicine 2018, 97, e11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Nishimura, Y.; Yukawa, M.; Seki, K.; Sekiya, S. Profile of Trace Element Concentrations in the Feto-Placental Unit in Relation to Fetal Growth. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossipal, E.; Krachler, M.; Li, F.; Micetic-Turk, D. Investigation of the Transport of Trace Elements Across Barriers in Humans: Studies of Placental and Mammary Transfer. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, L.; García-Vicent, C.; López, J.; Torró, M.I.; Lurbe, E. Assessment of Ten Trace Elements in Umbilical Cord Blood and Maternal Blood: Association with Birth Weight. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Rodríguez, R.; Luzardo, O.P.; González-Antuña, A.; Boada, L.D.; Almeida-González, M.; Camacho, M.; Zumbado, M.; Acosta-Dacal, A.C.; Rial-Berriel, C.; Henríquez-Hernández, L.A. Occurrence of 44 Elements in Human Cord Blood and Their Association with Growth Indicators in Newborns. Environ. Int. 2018, 116, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhadi, A.; Rayis, D.A.; Abdullahi, H.; Elbashir, L.M.; Ali, N.I.; Adam, I. Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of Zinc and Copper in Active Labor Versus Elective Caesarean Delivery at Khartoum Hospital, Sudan. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 169, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galinier, A.; Périquet, B.; Lambert, W.; Garcia, J.; Assouline, C.; Rolland, M.; Thouvenot, J.-P. Reference Range for Micronutrients and Nutritional Marker Proteins in Cord Blood of Neonates Appropriated for Gestational Ages. Early Hum. Dev. 2005, 81, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.; Accrombessi, M.; Fievet, N.; Yovo, E.; Massougbodji, A.; Le Bot, B.; Glorennec, P.; Bodeau-Livinec, F.; Briand, V. Toxics (Pb, Cd) and Trace Elements (Zn, Cu, Mn) in Women during Pregnancy and at Delivery, South Benin, 2014–2015. Environ. Res. 2018, 167, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Weng, K.P.; Lin, C.C.; Wang, C.C.; Lee, C.T.; Ger, L.P.; Wu, M.T. Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of Mercury, Manganese, Iron, and Copper in Southern Taiwan: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2017, 80, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, O.; Paz-Tal, O.; Lazer, T.; Aricha-Tamir, B.; Mazor, M.; Wiznitzer, A.; Sheiner, E. Severe Pre-eclampsia Is Associated with Abnormal Trace Elements Concentrations in Maternal and Fetal Blood. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyłowski, R.; Lewicka, I.; Grzesiak, M.; Gaj, Z.; Oszukowski, P.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Suliburska, J. Evaluation of Mineral Concentrations in Maternal Serum before and after Birth and in Newborn Cord Blood Postpartum—Preliminary Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 182, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, K.; Kosik-Bogacka, D.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N.; Malinowski, W.; Szymański, S.; Mularczyk, M.; Tomska, N.; Rotter, I. Interactions between 14 Elements in the Human Placenta, Fetal Membrane and Umbilical Cord. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-M.; Wu, X.-Y.; Huang, K.; Yan, S.-Q.; Li, Z.-J.; Xia, X.; Pan, W.-J.; Sheng, J.; Tao, Y.-R.; Xiang, H.-Y.; et al. Trace Element Profiles in Pregnant Women’s Sera and Umbilical Cord Sera and Influencing Factors: Repeated Measurements. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.P.; Fujiwara, T.; Umezaki, M.; Furusawa, H.; Ser, P.H.; Watanabe, C. Cord Blood Levels of Toxic and Essential Trace Elements and Their Determinants in the Terai Region of Nepal: A Birth Cohort Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 147, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, S.; Altaf, W.; Vohra, N.; Bautista, M.L.; Harper, R.G.; Wapnir, R.A. Effect of Gestational Age on Cord Blood Plasma Copper, Zinc, Magnesium and Albumin. Early Hum. Dev. 2002, 69, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesik-Gąsior, J.; Sawicki, J.; Pieczykolan, A.; Bień, A. Content of Selected Heavy Metals in the Umbilical Cord Blood and Anthropometric Data of Mothers and Newborns in Poland: Preliminary Data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiri, B.; Martín-Carrasco, I.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; García-Barrera, T.; Gómez-Ariza, J.L.; González-Domínguez, R. Monitoring of Metals and Metalloids from Maternal and Cord Blood Samples in a Population from Seville (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Jia, X.; Shi, H.; Gong, X.; Ma, J.; Gan, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y. An Evaluation of Exposure to 18 Toxic and/or Essential Trace Elements in Maternal and Cord Plasma during Pregnancy at Advanced Maternal Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.M.; Mikes, B.A. Preterm Labor. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, S.; Nieboer, E.; Odland, J.Ø.; Wilsgaard, T.; Veyhe, A.S.; Sandanger, T.M. Changes in Maternal Blood Concentrations of Selected Essential and Toxic Elements during and after Pregnancy. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Li, T.; Zhang, C.; Huang, H.; Wu, Y. Association between Plasma Trace Element Concentrations in Early Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Shanghai, China. Nutrients 2022, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.-C.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Fan, P.; Ma, R.; Ma, J.; Luo, K.; Yan, C.-H.; et al. Maternal Blood Concentrations of Toxic Metal(loid)s and Trace Elements from Preconception to Pregnancy and Transplacental Passage to Fetuses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, T.; Banu, S.; Nahar, Q.; Ahsan, M.; Khan, M.N.; Islam, S.N. Serum Trace Elements Levels in Preeclampsia and Eclampsia: Correlation with the Pregnancy Disorder. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 152, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sak, S.; Barut, M.; Çelik, H.; Incebiyik, A.; Ağaçayak, E.; Uyanikoglu, H.; Kirmit, A.; Sak, M. Copper and Ceruloplasmin Levels Are Closely Related to the Severity of Preeclampsia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, A.Z.; Atakul, N.; Selek, S.; Atamer, Y.; Sarıkaya, U.; Yıldız, T.; Demirel, M. Maternal Serum Levels of Zinc, Copper, and Thiols in Preeclampsia Patients: A Case-Control Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harma, M.; Harma, M.; Kocyigit, A. Correlation between Maternal Plasma Homocysteine and Zinc Levels in Preeclamptic Women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2005, 104, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeeinia, A.; Tabandeh, A.; Khajeniazi, S.; Marjani, A.J. Serum Copper, Zinc and Lipid Peroxidation in Pregnant Women with Preeclampsia in Gorgan. Open Biochem. J. 2014, 8, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, Z.; Gür, E.; Develioğlu, O. Serum Iron and Copper Status and Oxidative Stress in Severe and Mild Preeclampsia. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2006, 24, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, T.; Sun, Z.; Wang, A.; Xiong, L. Epidemiology and Major Subtypes of Congenital Heart Defects in Hunan Province, China. Medicine 2018, 97, e11770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Bloom, M.S.; Nie, Z.; Han, F.; Mai, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, S.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, J. Associations between Toxic and Essential Trace Elements in Maternal Blood and Fetal Congenital Heart Defects. Environ. Int. 2017, 106, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.; Pourbadakhshan, N.; Farhat, A.S.; Vaezi, A. A Comparative Study of Micronutrient Levels in Pregnant Women with and without Gestational Diabetes. Rev. Clin. Med. 2023, 10, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanravan, N.; Mesri Alamdari, N.; Ghavami, A.; Mousavi, R.; Alipour, S.; Ebrahimi-Mamaghani, M. Serum Levels of Copper, Zinc and Magnesium in Pregnant Women with Impaired Glucose Tolerance Test: A Case-Control Study. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, M.; Huang, Z.; Sheng, L.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, G. Elemental Contents in Serum of Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2002, 88, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yu, P.; Liu, Z.; Tao, J.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Wei, H.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Kang, H.; et al. Inverse Association between Maternal Serum Concentrations of Trace Elements and Risk of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: A Nested Case–Control Study in China. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiudzu, G.; Choko, A.T.; Maluwa, A.; Huber, S.; Odland, J. Maternal Serum Concentrations of Selenium, Copper, and Zinc during Pregnancy Are Associated with Risk of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: A Case-Control Study from Malawi. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 9435972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.K.; Arain, A.L.; Shao, J.; Chen, M.; Xia, Y.; Lozoff, B.; Meeker, J.D. Distribution and Predictors of 20 Toxic and Essential Metals in the Umbilical Cord Blood of Chinese Newborns. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Lubiński, J. Serum Selenium Level in Early Healthy Pregnancy as a Risk Marker of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golalipour, M.J.; Vakili, M.A.; Mansourian, A.R.; Mobasheri, E. Maternal Serum Zinc Deficiency in Cases of Neural Tube Defect in Gorgan, North Islamic Republic of Iran. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2009, 15, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.C.; Shahidullah, M.; Mannan, M.A.; Noor, M.K.; Saha, L.; A Rahman, S. Maternal and Neonatal Serum Zinc Level and Its Relationship with Neural Tube Defects. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010, 28, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, T.; Tonni, S.; Shammi, R.S.; Khan, M.H.; Islam, S.; Hoque, M.M.M.; Meghla, N.T.; Kabir, H. Comprehensive Evaluation of Heavy Metals in Surface Water of the Upper Banar River, Bangladesh. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol. 2023, 13, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaguru, A.; Gada, S.; Potpalle, D.; Dinesh Eshwar, M.; Purwar, D. The Prevalence of Low Birth Weight among Newborn Babies and Its Associated Maternal Risk Factors: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e38587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, K.; Otake, T.; Yoshinaga, J.; Ikegami, M.; Suzuki, E.; Naruse, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Shibuya, N.; Yasumizu, T.; Kato, N. Cadmium, Lead, and Selenium in Cord Blood and Thyroid Hormone Status of Newborns. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2007, 119, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, S.Z.; Forouhari, S.; Dabbaghmanesh, M.H.; Sayadi, M.; Bakhshayeshkaram, M.; Vaziri, F.; Tavana, Z. A Prospective Study of Selenium Concentration and Risk of Preeclampsia in Pregnant Iranian Women: A Nested Case-Control Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 152, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Chan, H.M.; Domingo, J.L.; Koriyama, C.; Murata, K. Placental Transfer and Levels of Mercury, Selenium, Vitamin E, and Docosahexaenoic Acid in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood. Environ. Int. 2018, 111, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Xu, C.; Lin, N.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, W. Lead, Mercury, and Cadmium in Umbilical Cord Serum and Birth Outcomes in Chinese Fish Consumers. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Sheng, L.; Qian, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, G. Changes of Serum Selenium in Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2001, 83, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Z. The Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight in 204 Countries and Territories from 1990 to 2019: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubio, C.; Abanga, W.A.; Zeng, V.; Bosoka, S.A.; Afetor, M.; Djokoto, S.K.; Baiden, F. Incidence of Low Birth Weight Among Newborns Delivered in Health Facilities in the Volta Region, 2019–2023. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, K.E.; Ferraro, Z.M.; Yockell-Lelievre, J.; Gruslin, A.; Adamo, K.B. Maternal-Fetal Nutrient Transport in Pregnancy Pathologies: The Role of the Placenta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 16153–16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Padhani, Z.A.; Rabbani, A.; Rind, F.; Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Impact of Dietary Interventions during Pregnancy on Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nutrients 2020, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.M.; Narchi, H. Preterm Nutrition and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernand, A.D.; Schulze, K.J.; Stewart, C.P.; West, K.P., Jr.; Christian, P. Micronutrient Deficiencies in Pregnancy Worldwide: Health Effects and Prevention. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Wright, C. Safety and Efficacy of Supplements in Pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 813–826, Erratum in Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 782. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, K.; Łanocha-Arendarczyk, N.; Kupnicka, P.; Szymański, S.; Malinowski, W.; Kalisińska, E.; Chlubek, D.; Kosik-Bogacka, D. Selected Metal Concentration in Maternal and Cord Blood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoul, I.R.; Sammour, R.N.; Diamond, E.; Shohat, I.; Tamir, A.; Shamir, R. Selenium Concentrations in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood at 24–42 Weeks of Gestation: Basis for Optimization of Selenium Supplementation to Premature Infants. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.K. Prediction and Prevention of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 234. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; An, H.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Yan, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Associations between Hair Levels of Trace Elements and the Risk of Preterm Birth among Pregnant Women: A Prospective Nested Case-Control Study in Beijing Birth Cohort (BBC), China. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettwiler, M.; Flynn, A.C.; Rigutto-Farebrother, J. Effects of Non-Essential “Toxic” Trace Elements on Pregnancy Outcomes: A Narrative Overview of Recent Literature Syntheses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohari, H.; Khajavian, N.; Mahmoudian, A.; Bilandi, R.R. Copper and Zinc Deficiency to the Risk of Preterm Labor in Pregnant Women: A Case-Control Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monangi, N.K.; Xu, H.; Fan, Y.; Khanam, R.; Khan, W.; Deb, S.; Pervin, J.; Price, J.T.; Kaur, L. Association of Maternal Prenatal Copper Concentration with Gestational Duration and Preterm Birth: A Multicountry Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, T.A.; Ahmad, I.M.; Zimmerman, M.C. Oxidative Stress and Preterm Birth: An Integrative Review. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2018, 20, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.N.; Carr, D.J.; David, A.L. Treatment of Poor Placentation and the Prevention of Associated Adverse Outcomes-What Does the Future Hold? Prenat. Diagn. 2014, 34, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, O.; Romero, R.; Jung, E.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Bosco, M.; Suksai, M.; Gallo, D.M.; Gotsch, F. Preeclampsia and Eclampsia: The Conceptual Evolution of a Syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S786–S803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.; Kitt, J.; Leeson, P.; Aye, C.Y.L.; Lewandowski, A.J. Preeclampsia: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Management, and the Cardiovascular Impact on the Offspring. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, L.C.; Cluver, C.A.; Kingdom, J.; Tong, S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2021, 398, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrar, S.A.; Martingano, D.J.; Hong, P.L. Preeclampsia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aouache, R.; Biquard, L.; Vaiman, D.; Miralles, F. Oxidative Stress in Preeclampsia and Placental Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumru, S.; Aydin, S.; Simsek, M.; Sahin, K.; Yaman, M.; Ay, G. Comparison of Serum Copper, Zinc, Calcium, and Magnesium Levels in Preeclamptic and Healthy Pregnant Women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2003, 94, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, L.R.; Tomich, P.G. Gestational Diabetes: Diagnosis, Classification, and Clinical Care. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 44, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lende, M.; Rijhsinghani, A. Gestational Diabetes: Overview with Emphasis on Medical Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raets, L.; Beunen, K.; Benhalima, K. Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Early Pregnancy: What Is the Evidence? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [CrossRef]

- Greene, N.D.; Copp, A.J. Neural Tube Defects. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 37, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Tang, P.; Wang, Y.; Han, N.; Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Ji, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Yan, L.; et al. Association between Maternal Serum Essential Trace Element Concentration in Early Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutr. Diabetes 2025, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, T.; Ni, F.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, L.; Yang, Q.; Gao, X.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; et al. Couples’ Preconception Urinary Essential Trace Elements Concentration and Spontaneous Abortion Risk: A Nested Case-Control Study in a Community Population. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-M.; Doyle, P.; Wang, D.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-C. The Role of Essential Metals in the Placental Transfer of Lead from Mother to Child. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avagliano, L.; Massa, V.; George, T.M.; Qureshy, S.; Bulfamante, G.P.; Finnell, R.H. Overview on Neural Tube Defects: From Development to Physical Characteristics. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengiz, B.; Söylemez, F.; Öztürk, E.; Çavdar, A.O. Serum Zinc, Selenium, Copper, and Lead Levels in Women with Second-Trimester Induced Abortion Resulting from Neural Tube Defects. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004, 97, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Qiu, X.; Wei, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Yin, S.; Jin, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Selenium Protects against the Likelihood of Fetal Neural Tube Defects Partly via the Arginine Metabolic Pathway. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, K. Epidemiological Aspects, Prenatal Screening and Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Beijing. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 777899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kang, Y.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Zeng, L.; Yan, H.; Dang, S. Maternal Zinc, Copper, and Selenium Intakes during Pregnancy and Congenital Heart Defects. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, P.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; Yu, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Z. High Maternal Selenium Levels Are Associated with Increased Risk of Congenital Heart Defects in the Offspring. Prenat. Diagn. 2019, 39, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ref. | Element | Biological Material | Analytical Technique | Pregnant Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Trimester | Levels (µg/L) | ||||

| [59] | Cu | Blood | AAS | - | 1st | - |

| 1798 | 2nd | 1168 ± 140 | ||||

| 2062 | 3rd | 1176 ± 140 | ||||

| [60] | Cu | Plasma | AAS | 36 | 1st | 1893 ± 498 |

| 49 | 2nd | 2163 ± 475 | ||||

| 37 | 3rd | 2145 ± 526 | ||||

| [61] | Cu | Serum | AAS | - | 1st | 1060 ± 120 |

| 56 | 2nd | 1070 ± 220 | ||||

| - | 3rd | 1120 ± 145 | ||||

| [62] | Cu | Plasma | AAS | 32 | 1st | 1593.6 b |

| 28 | 2nd | 1830.4 b | ||||

| 18 | 3rd | 1977.6 b | ||||

| [63] | Cu | Plasma | AAS | 41 | 1st | 1667 ± 418 |

| - | 2nd | - | ||||

| 35 | 3rd | 2582 ± 566 | ||||

| [64] | Cu | Plasma | AAS | 26 | 1st | 866 ± 138 |

| 23 | 2nd | 1116 ± 279 | ||||

| 32 | 3rd | 1140 ± 297 | ||||

| [57] | Cu | Plasma | AAS | 392 | 1st | 1980 ± 570 |

| 307 | 2nd | 2360 ± 590 | ||||

| 299 | 3rd | 2550 ± 530 | ||||

| Zn | Plasma | AAS | 391 | 1st | 910 ± 270 | |

| 304 | 2nd | 780 ± 270 | ||||

| 299 | 3rd | 740 ± 210 | ||||

| Se | Plasma | AAS | 410 | 1st | 48.4 ± 10.5 | |

| 151 | 2nd | 42.3 ± 9.08 | ||||

| 130 | 3rd | 37.3 ± 9.79 | ||||

| [65] | Cu | Serum | AAS | 73 | 1st | 1475 ± 346 |

| 30 | 2nd | 1971 ± 240 | ||||

| 38 | 3rd | 2042 ± 418 | ||||

| Zn | Serum | AAS | 73 | 1st | 713 ± 129 | |

| 30 | 2nd | 611 ± 86.3 | ||||

| 38 | 3rd | 585 ± 115 | ||||

| Se | Serum | AAS | 73 | 1st | 109 ± 20.1 | |

| 30 | 2nd | 99.0 ± 24.4 | ||||

| 38 | 3rd | 85.5 ± 12.8 | ||||

| [66] | Cu | Serum | HR-ICP-MS | 291 | 1st | 1575 (897–3660) a |

| 555 | 2nd | 1986 (1226–3435) a | ||||

| 491 | 3rd | 2082 (1210–3750) a | ||||

| Zn | Serum | HR-ICP-MS | 291 | 1st | 832 (577–1300) a | |

| 555 | 2nd | 73.0 (53.4–103) a | ||||

| 491 | 3rd | 71.0 (49.4–110) a | ||||

| Se | Serum | HR-ICP-MS | 291 | 1st | 77.6 (44.0–112) a | |

| 555 | 2nd | 76.0 (42.5–112) a | ||||

| 491 | 3rd | 65.0 (38.0–105) a | ||||

| [67] | Cu | Serum | AAS | 34 | 1st | 1434 ± 971 |

| 44 | 2nd | 1650 ± 483 | ||||

| 52 | 3rd | 1692 ± 755 | ||||

| Se | Serum | AAS | 34 | 1st | 107 ± 15.8 | |

| 44 | 2nd | 83.0 ± 17.4 | ||||

| 52 | 3rd | 79.8 ± 19.0 | ||||

| [44] | Cu | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 1st | 1309 ± 435 |

| 162 | 2nd | 1720 ± 389 | ||||

| - | 3rd | 1932 ± 285 | ||||

| Zn | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 1st | 795 ± 150 | |

| 162 | 2nd | 745 ± 161 | ||||

| - | 3rd | 653 ± 149 | ||||

| [7] | Cu | Serum | AAS | 177 | 1st | 1323 ± 382 |

| 174 | 2nd | 1649 ± 400 | ||||

| - | 3rd | - | ||||

| Zn | Serum | AAS | 177 | 1st | 813 ± 319 | |

| 174 | 2nd | 743 ± 225 | ||||

| - | 3rd | - | ||||

| Se | Serum | AAS | 177 | 1st | 44.9 ± 9.23 | |

| 174 | 2nd | 47.2 ± 10.9 | ||||

| - | 3rd | - | ||||

| [69] | Zn | Serum | AAS | 60 | 1st | 749 ± 91.0 |

| 60 | 2nd | 731 ± 106 | ||||

| 60 | 3rd | 684 ± 99 | ||||

| [70] | Cu | Serum | AAS | 32 | 1st | 1340 ± 400 |

| 40 | 2nd | 1730 ± 330 | ||||

| 45 | 3rd | 1210 ± 400 | ||||

| Zn | Serum | AAS | 31 | 1st | 1030 ± 270 | |

| 44 | 2nd | 1170 ± 450 | ||||

| 50 | 3rd | 1110 ± 280 | ||||

| [56] | Cu | Serum | AAS | 7 | 1st | 1053 ± 498 |

| 12 | 2nd | 1616 ± 304 | ||||

| 19 | 3rd | 1689 ± 344 | ||||

| Zn | Serum | AAS | 7 | 1st | 829 ± 253 | |

| 12 | 2nd | 846 ± 329 | ||||

| 19 | 3rd | 620 ± 142 | ||||

| [71] | Cu | Serum | ICP-MS | 52 | 1st | 1120 b |

| 97 | 2nd | 1670 b | ||||

| 96 | 3rd | 1780 b | ||||

| Zn | Serum | ICP-MS | 52 | 1st | 66.0 b | |

| 97 | 2nd | 55.0 b | ||||

| 96 | 3rd | 94.0 b | ||||

| Se | Serum | ICP-MS | 52 | 1st | 97.0 b | |

| 97 | 2nd | 94.0 b | ||||

| 96 | 3rd | 91.0 b | ||||

| 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu (μg/L) | 1000–1900 | 1100–2400 | 1100–2600 |

| Zn (μg/L) | 70–910 | 70–810 | 70–750 |

| Se (μg/L) | 45–110 | 42–100 | 37–91 |

| Reference | Study Design | Country | N | Biological Material | Analytical Technique | Cu Levels (µg/L) | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | Cord | |||||||

| [42] | Cross-sectional | Cairo, Egypt | 150 (40 preterm + 35 full-term) and their mothers | Serum | FAAS | Preterm: 1400 ± 330 Full-term: 1690 ± 390 | Preterm: 750 ± 280 Full-term: 1370 ± 260 | Maternal and cord serum Cu levels differed significantly and were positively correlated (ρ = 0.625). Cord Cu was higher in term than preterm neonates and differed between AGA and SGA infants. Cord Cu positively correlated with gestational age (ρ = 0.851), birth weight, length, and head circumference. Maternal Cu also correlated positively with gestational age and newborn anthropometrics, with higher maternal Cu linked to better outcomes |

| [36] | Cross-sectional | Kuwait | 39 | Blood | GFAAS | 2406 ± 65.3 | 853 ± 54.5 | Maternal Cu was higher than cord Cu (maternal/cord ratio 0.32 ± 0.03), with a negative correlation between cord Cu and birth weight. Transplacental Cu transfer appears to occur via passive diffusion. Maternal Cu/Zn ratio (3.60 ± 0.22 µg/L) exceeded cord levels (0.77 ± 0.09 µg/L). |

| [52] | Cross-sectional | Jordan | 186 | Serum | AAS | 2360 ± 360 | 490 ± 240 | Significantly higher levels of Cu in cord blood than in maternal blood. From the 1st to the 3rd trimester of pregnancy, serum Cu levels were significantly increased. No significant association between Cu levels in maternal and cord blood and birth weight (3.34 ± 0.44 kg). |

| [77] | Cross-sectional | Valencia, Spain | 54 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 1460 ± 515 | 260 ± 85.1 | A positive correlation between cord blood Cu levels and maternal blood (ρ = 0.484). Significant correlation between cord Cu levels and birth weight (r = −0.25). Cord blood Cu levels were significantly higher among SGA infants than in AGA and LGA infants. |

| [33] | Cross-sectional | Tarragona, Spain | 53 | Blood | SF-ICP-MS | 1664 | 623 | Significantly lower Cu levels in cord blood than in maternal blood, indicating limited transplacental transfer. Significantly higher Cu levels at delivery compared to the 1st trimester (1664 μg/L vs. 1302 μg/L). No significant correlation in Cu levels between maternal and cord blood. |

| [53] | Cross-sectional | Arctic Canada | 352 | Plasma | GF-AAS | 2097 | 357 | Maternal Cu levels were significantly higher than in cord blood. |

| [78] | Cross-sectional | Canary Islands, Spain | 471 | Blood | ICP-MS | - | 402 ± 194 | No significant relationship between cord Cu levels and birth weight. |

| [47] | Prospective | Bangladesh | 745 | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 475 | A significant negative association between cord blood Cu levels and birth weight. |

| [54] | Cross-sectional | Spain and Belgium | 66 | Serum | F-AAS | 1988 ± 476 | 311 ± 216 | Cord Cu was higher than maternal Cu, and Cu and Zn were negatively correlated (r = −0.35). Maternal Cu/Zn ratio exceeded cord levels, and maternal age correlated with the cord Cu/Zn ratio. Gestational age was positively associated with Cu, but Cu was not linked to birth weight. |

| [79] | Case–control | Sudan | 104 | Serum | F-AAS | Vaginal delivery: 788 Cesarean delivery: 924 | Vaginal delivery: 435 Cesarean delivery: 322 | Maternal Cu did not differ by delivery mode, but cord Cu was higher after vaginal delivery. Maternal and cord Cu levels were not significantly correlated. |

| [23] | Case–control | Sweden | 80 | Erythrocytes | ICP-MS | 437 | 455 | Cu levels did not differ between maternal and cord blood or between women with and without an anthroposophic lifestyle. |

| [80] | Cross-sectional | France | 510 (262 full-term + 248 preterm) | Serum | FAAS | - | Full-term: 425 ± 133 Preterm: 286 ± 127 | Cord blood Cu was lower in preterm than term infants, unaffected by gender, and increased steadily with gestational age from 26 to 42 weeks. |

| [81] | Cross-sectional | Benin | 60 | Blood | ICP-MS | 1609 | 627 | Cu levels were significantly lower in cord blood than in maternal blood. Blood levels of Cu were significantly higher in maternal blood (collected at delivery) than during the 1st trimester of pregnancy. |

| [82] | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | 145 | Blood | ICP-MS | 1470 | 730 | Maternal and cord Cu were positively correlated (ρ = 0.21), with cord Cu lower than maternal. Prenatal vitamin use (>3×/week) was linked to lower maternal Cu, and maternal age showed a borderline association with Cu levels. |

| [48] | Prospective | Bangladesh | 745 | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 475 | Cu levels in cord blood were not associated with the risk of preterm birth. |

| [28] | Cross-sectional | Jakarta, Indonesia | 51 | Serum | ICP-MS | Term: 2226 Preterm: 2153 | Term: 322 Preterm: 206 | Cu levels were higher in cord blood from the term group (n = 25) than from the preterm group (n = 26). |

| [83] | Case–control | NP | 43 cases with severe PE and 80 healthy pregnant women | Serum | ICP-MS | Cases: 2239 ± 575 Controls: 1050 ± 877 | Cases: 526 ± 211 Controls: 1109 ± 885 | Maternal blood Cu levels were significantly higher in PE group than in controls. Cu levels were significantly lower in maternal and cord blood from the PE group than from controls |

| [45] | Cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 44 | Plasma | ICP-MS | - | 660 | Cord blood Cu levels were not significantly associated with birth weight, chest circumference, gestational age, birth length, and head circumference. |

| [84] | Cross-sectional | Greater Poland region | 64 | Serum | F-AAS | 1910 ± 400 | 360 ± 90 | Cord serum Cu levels were significantly lower than in maternal serum. |

| [85] | Cross-sectional | Gryfino, Poland | 136 | Blood | ICP-OES | 910 ± 410 | 340 ± 130 | Maternal Cu was over twice that of cord blood (p < 0.05), positively associated with gestational age, and negatively correlated with newborn head circumference (r = −0.29). |

| [72] | Prospective cohort | NP | 68 | Serum | FEAS | with PPROM: 2020 ± 670 without PPROM: 2010 ± 630 | with PPROM: 340 ± 220 without PPROM: 390 ± 250 | Cu levels did not differ between the PPROM (n = 35) and non-PPROM groups (n = 33) in either maternal serum or cord serum. |

| [51] | Prospective case–control | Israel | 80 | Plasma | ICP-MS | Active: 1050 ± 877 Elective CD: 1046 ± 835 | Active: 1109 ± 885 Elective CD: 625 ± 658 | Significantly higher Cu levels in cord blood during active labor compared to elective cesarean delivery (CD). |

| [25] | Cross-sectional | Gwangju, South Korea | 81 | Plasma | AAS | 1140 ± 297 | 575 ± 109 | Plasma Cu levels in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters were 866 ± 138, 1116 ± 279 and 1140 ± 297 µg/L, respectively. Plasma Cu levels were significantly higher during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters than in the 1st. Cu levels in cord blood were about 50% lower than in maternal blood (p < 0.05). |

| [86] | Cross-sectional | Ma’anshan, China | 3416 | Serum | ICP-MS | the 1st trimester: 1530 the 2nd trimester: 2030 | 300 | Cord serum Cu was lower than maternal serum, and Cu levels differed between trimesters. Multivitamin use during pregnancy was positively associated with maternal Cu. |

| [49] | Case–control | Varanasi, India | 33 cases and 18 controls | Plasma | Spectrophotometry | - | 425 ± 82.3 | Copper levels were significantly lower in cord blood from women with PE (n = 19) (349 ± 95.3 µg/L) and eclampsia (n = 14) (261 ± 72.1 µg/L) than in controls (424 ± 82.3 µg/L). |

| [87] | Cross-sectional | Terai, Nepal | 100 | Blood | ICP-MS | - | 643 | Cord blood Cu levels were not associated with maternal age, socioeconomic status, living environment, or tobacco smoking. |

| [88] | Cross-sectional | Manhasset, New York, USA | 35 | Plasma | AAS | 1715 ± 268 | 360 ± 77 | No significant differences in maternal plasma Cu levels with gestational age. However, the maternal/cord plasma Cu ratio increased with gestational age. |

| [35] | Cross-sectional | South Africa | 62 | Blood | ICP-MS | 1730 | 657 | No significant association between maternal and cord blood Cu levels. |

| [26] | Prospective cohort | China | 1568 | Serum | AAS | 1970 ± 383 | - | Serum Cu levels increased significantly from the 1st to the 3rd trimester and were significantly higher than pre-pregnancy levels. Serum Cu levels were significantly lower in the group with PROM than in controls. |

| [89] | Cross-sectional | Lucknow, India | 54 | Blood | FAAS | 2170 ± 790 | 1410 ± 900 | Maternal Cu was higher and cord Cu slightly lower in low birth weight infants, but not significantly. Cu levels did not differ by gestational age, though cord Cu showed a weak positive correlation with gestational age. |

| [41] | Cross-sectional | Serbia | 125 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 2127 ± 523 | 276 ± 114 | Cu levels differed significantly between maternal and cord blood and were positively correlated. Cord Cu was higher in infants of mothers aged 20–25 than 31–35 years. |

| [90] | Longitudinal | Khoy, Iran | 162 | Serum | ICP-MS | 1932 ± 285 | 570 ± 138 | Differences in sera Cu levels during the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters (1309 ± 435, 1720 ± 389, 1932 ± 285 μg/L, respectively). Cu levels in cord blood serum were significantly lower than in maternal serum. |

| [21] | Case–control | Harran, Turkey | 144 | Serum | AAS | Cases: 2831 ± 1017 Controls: 2402 ± 744 | Cases: 790 Controls: 517 | Copper levels in maternal and cord serum in the NTD group were significantly higher than in controls. The Cu/Zn ratio in mothers of neonates with NTD was significantly higher (3.80 ± 2.10 vs. 2.60 ± 1.20) than in controls. |

| [91] | Cross-sectional | Seville, Spain | 100 | Blood | ICP-MS | 1632 | 655 | Cu levels in the women’s blood were almost three times higher than those found in cord blood (p < 0.05). |

| [92] | Cross-sectional | Lublin, Poland | 134 | Blood | HR-ICP-OES | - | 750 ± 204 | A positive association between cord blood Cu levels and weight gain in pregnant women. The Cu/Zn ratio was significantly associated with the head circumference of the newborn. |

| [91] | Prospective cohort | Beijing, China | 48 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 1845 | 250 | Cu levels increased during pregnancy (1273 vs. 1797 vs. 1845 µg/L). Cu levels were significantly lower in cord than in maternal plasma. |

| [93] | Prospective cohort | Norway | 211 | Blood | SF-ICP-MS | 1650 | - | Blood Cu levels increased significantly during pregnancy and decreased 6 weeks postpartum. |

| [93] | Longitudinal | Shanghai, China | 100 | Blood (at 4 time points: preconception, GW 16, 24, and 32) | ICP-MS | 1464 ± 147 | 577 ± 93.0 | Maternal blood Cu levels were higher during pregnancy than in the preconception period. Maternal blood Cu levels correlated between preconception and 24 weeks of gestation. From conception to the 3rd trimester, maternal Cu levels were positively correlated. |

| [43] | Case–control | Nottingham, England | 55 cases with PE, 60 healthy normotensive pregnant women, and 30 healthy non-pregnant women | Plasma | ICP-MS | 1541 | 232 | Maternal plasma Cu was higher in women with PE (1606 µg/L) than in controls (1541 µg/L), with no difference between early- and late-onset PE. Cord Cu levels were lower than maternal levels but higher in infants of PE mothers (335 µg/L) than controls (232 µg/L). Elevated cord Cu was significant in late-onset PE only. |

| [30] | Case–control | Kermanshah province, Iran | 57 cases with diabetes and 54 controls | Serum | ICP-MS | Cases: 1020 ± 710 Controls: 980 ± 746 | - | No significant differences in maternal serum Cu between cases and controls. In controls, only head circumference showed a significant negative correlation with Cu (ρ = −0.33). In cases, Cu levels were negatively correlated with growth measures, particularly birth weight (ρ = −0.374) and head circumference (ρ = −0.345). Multivariate analysis showed that in women with diabetes, higher Cu levels adversely affected neonatal weight and head circumference. |

| [94] | Case–control | Fujian, China | 120 cases with spontaneous preterm birth and 120 controls | Blood | ICP-MS | Cases: 650.87 Controls: 618.94 | - | Blood Cu levels were significantly higher in spontaneous preterm birth cases than in controls. Note: Maternal blood was collected between 10 and 13 weeks of gestation. |

| [59] | Case–control | Guangdong, China | 515 cases with preterm births (PTB) and 595 controls | Blood | ICP-MS | - | Cases: 540 Controls: 516 | Cord blood Cu levels were significantly higher in cases than in controls. Cord blood Cu levels were positively associated with PTB; it was hypothesized that Cu could be a risk factor for PTB at relatively high levels. |

| [34] | Cross-sectional | Argentina | 696 | Blood (36 ± 12 h postpartum) | ICP-MS | 1782 | - | Blood Cu levels decreased with higher parity but increased with maternal age. Higher maternal Cu was linked to longer gestation, as well as lower birth weight, shorter neonatal length, and smaller head circumference. |

| [22] | Cross-sectional | Isfahan, Iran | 263 | Blood (collected during the 1st trimester) | ICP-MS | 213.94 ± 115.85 | - | No significant association between blood Cu levels and birth size outcomes. |

| [95] | Retrospective | Guangzhou, China | 11,222 pregnant women and 545 non-pregnant women | Blood | ICP-MS | 1447.7 | - | Cu levels were higher in pregnant women than in controls, and at 12 weeks’ gestation, older pregnant women (>35) had higher Cu levels than younger women (<35) |

| [27] | Cross-sectional | Dongguan City, China | 271 pregnant women, of whom 97 were diagnosed with mild PE, 64 with severe PE, and 110 were normotensive healthy pregnant women. | Serum | ICP-MS | 1364 | - | Serum Cu was lower in controls (1364 μg/L) than in women with PE, increasing from mild PE (1940 μg/L) to severe PE (2841 μg/L). These results suggest that higher Cu levels may contribute to the onset and severity of PE. |

| [96] | Cross sectional | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 44 PE, 33 eclampsia, and 27 normotensive healthy pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 1016 ± 127 | - | Maternal serum Cu was highest in controls (1016 ± 127 μg/L), slightly lower in PE (1110 ± 127 μg/L), and lowest in eclampsia (952 ± 127 μg/L), with significant differences among groups. |

| [97] | Prospective | Diyarbakır, Turkey | 179 pregnant women, 58 healthy pregnant women, 71 mild PE, 26 severe PE, and 24 HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and Low Platelet count, a form of severe preeclampsia) syndrome | Serum | AAS | 626 | - | Serum Cu was highest in HELLP (2099 ± 286 μg/L), followed by severe PE (1602 ± 208 μg/L), mild PE (812 ± 118 μg/L), and lowest in healthy pregnancies (626 ± 256 μg/L). All differences were significant, showing Cu levels rise with the severity of hypertensive disorders. |

| [29] | Case–control | Sudan | 50 PE cases and 50 healthy pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 1036 | - | No significant differences in Cu levels between PE group (1116 μg/L) and controls (1036 μg/L). |

| [98] | Observational case–control | Istanbul, Turkey | 88 pregnant women (in their 3rd trimester) included 43 preeclampsia patients and 45 normotensive pregnant women as controls. | Serum | Spectrophotometry | 1952 | - | Cu levels increased during pregnancy. PE cases had significantly higher Cu levels (2245 μg/L) than controls (1952 μg/L) |

| [99] | Case–control | Sanliurfa, Turkey | 24 women with PE and 44 normotensive pregnant women | Plasma | AAS | 31.60 ± 11.74 µg/g protein | - | Cu levels in PE group (47.9 ± 19.8 µg/g protein) were significantly higher than in controls (31.60 ± 11.74 µg/g protein). |

| [24] | Case–control | Nnewi, Nigeria | Of the total 102 pregnant women, 48 were non-preeclamptic while 54 were with PE | Serum | AAS | 534 ± 114 | - | Cu levels in PE group (1055 ± 201 μg/L) were significantly higher than in controls (534 ± 114 µg/L). |

| [100] | Case–control | Gorgan, Iran | 100 pregnant women, 50 healthy pregnant women and 50 women with PE | Serum | AAS | 1300 ± 340 | - | Cu levels in PE women (2400 ± 640 μg/L) were significantly higher than in controls (1300 ± 340 μg/L). |

| [19] | Case–control | Bangladesh | 50 cases of PE, with gestational period > 20 weeks and 58 normotensive pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 2580 ± 60.0 | - | Copper levels in PE women (1980 ± 100 μg/L) were significantly lower than in controls (2580 ± 60.0 μg/L). |

| [101] | Case–control | Bursa, Turkey | Thirty healthy, 30 mild PE and 30 severe PE pregnant women (31–38 week of pregnancy) | Serum | Spectrophotometry | 1590 ± 380 | - | Cu levels in the severe PE group (1940 ± 520 μg/L) were higher than in the mild PE group (1880 ± 480 μg/L). Both groups had significantly higher Cu levels than healthy controls (1590 ± 380 μg/L). |

| [102] | Case–control | Ankara, Turkey | 14 pregnant women with babies with NTDs in 2nd trimester and 14 pregnant women with ultrasound- normal fetuses as a control group | Serum | AAS | 2073 ± 377 | - | Cu levels in cases (2331 ± 221 µg/L) were significantly higher than in controls (2073 ± 377 µg/L) |

| [103] | Case–control | China | 112 pregnant women with babies with CHD and 109 pregnant women as a control | Plasma | ICP-MS | 897 | - | Cu levels in cases (838 μg/L) were significantly lower than in health controls (897 μg/L) |

| [104] | Case–control | Iran | 50 pregnant women with GDM and 50 healthy pregnant women as a control group | Serum from arterial blood | NP | 1666 ± 442 | - | No significant difference in serum Cu levels between cases (1671 ± 336 μg/L) and controls (1666 ± 442 μg/L). |

| [105] | Case–control | Iran | 46 pregnant women with impaired glucose tolerance and 35 healthy pregnant women | Serum | Spectrophotometry | 805 ± 386 | - | Cu levels in pregnant women with impaired glucose tolerance (476 ± 204 μg/L) were significantly lower than in controls (804 ± 386 μg/L). |

| [106] | Case–control | China | 251 women divided in four groups: 1. Normal pregnant women 2. Group pregnant women with impaired glucose tolerance 3. Group Pregnant women with GDM, and 4. Group: normal non pregnant women | Serum | ICP-AES | 1700 | Cu levels were significantly higher in pregnant women (1700 ± 260 μg/L) than in non-pregnant women (914 ± 86 μg/L). No significant difference was found between women with impaired glucose tolerance (1790 ± 360 μg/L) and normoglycemic pregnant women. Women with GDM showed significantly higher Cu levels (1960 ± 560 μg/L) compared to controls (1700 ± 260 μg/L). | |

| [107] | Case–control | China | 192 cases with PTB and 282 women with full term delivery. Measuring was performed in 1st and 2nd trimester | Serum | ICP-MS | 1824 | Copper levels in cases (1795 μg/L) were not significantly different from control group (1824 μg/L). | |

| [108] | Case–control | Malawi | Cases were defined as 91 preterm pregnancies of gestation 26–37 weeks while control were 90 women with full term | Serum | ICP-MS | 2390 | - | Copper levels in women who had PTB (2610 μg/L) were significantly higher than in women who delivered at term (2390 μg/L). |

| Reference | Study Design | Country | N | Biological Material | Analytical Technique | Zn Levels (µg/L) | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | Cord | |||||||

| [42] | Cross-sectional | Cairo, Egypt | 150 (40 preterm + 35 full-term) and their mothers | Serum | FAAS | Preterm: 960 ± 150 Full-term: 1090 ± 150 | Preterm: 730 ± 130 Full-term: 880 ± 180 | Maternal and cord serum Zn differed significantly and were positively correlated (ρ = 0.644). Cord Zn did not differ between AGA and SGA infants but was positively associated with gestational age (ρ = 0.305), birth weight, length, and head circumference. Maternal serum Zn was also positively correlated with gestational age and neonatal anthropometric measures, with higher maternal Zn linked to better outcomes |

| [36] | Cross-sectional | Kuwait | 39 | Blood | GFAAS | 696 ± 34.3 | 1112 ± 60.9 | Cord Zn was higher than maternal blood (maternal/cord ratio: 1.55 ± 0.08). Birth weight was not associated with Zn, but cord Zn was negatively linked to placental weight (450–800 g). The study suggests transplacental Zn transfer occurs via active transport and that blood Zn is not a reliable marker of fetal growth |

| [52] | Cross-sectional | Jordan | 186 | Serum | AAS | 680 ± 100 | 1140 ± 230 | Serum Zn was lower in cord blood than maternal blood and declined from the 1st to 3rd trimester. Cord Zn was positively correlated with birth weight (ρ = 0.723). In the 3rd trimester, anemic women (Hb < 11 g/dL) had lower serum Zn than non-anemic controls, and cord Zn remained positively associated with birth weight in both groups |

| [77] | Cross-sectional | Valencia, Spain | 54 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 757 ± 150 | 692 ± 153 | No significant association between cord blood Zn levels with SGA (n = 11), AGA (n = 30), or LGA infants (n = 13). |

| [33] | Cross-sectional | Tarragona, Spain | 53 | Blood | SF-ICP-MS | 6708 | 2311 | Zn levels were significantly lower in cord than in maternal blood, indicating limited. Zn levels were significantly higher at delivery compared to 1st trimester (6708 μg/L vs. 6147 μg/L). No significant correlation between maternal blood and cord blood Zn levels. |

| [53] | Cross-sectional | Arctic Canada | 352 | Plasma | F-AAS | 555 | 986 | Cord blood Zn levels were significantly higher than in maternal blood. |

| [78] | Cross-sectional | Canary Islands, Spain | 471 | Blood | ICP-MS | - | 1179 ± 417 | No significant association between cord Zn levels and birth weight. |

| [47] | Prospective | Bangladesh | 745 | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 1209 | No significant association between cord blood Zn levels and birth weight. |

| [54] | Cross-sectional | Spain and Belgium | 66 | Serum | F-AAS | 1548 ± 848 | 1959 ± 627 | Cord Zn levels were higher than maternal levels, with a significant negative correlation (r = −0.35). The maternal Cu/Zn ratio was higher than in cord blood and positively correlated with maternal age. Maternal Zn increased with gestational age, but Zn was not associated with birth weight |

| [79] | Case–control | Sudan | 104 | Serum | F-AAS | Vaginal delivery: 870 Cesarean delivery: 761 | Vaginal delivery: 978 Cesarean delivery: 815 | Maternal and cord serum Zn were higher after vaginal delivery than cesarean section. Cord Zn was significantly associated with maternal levels, though no overall correlation between maternal and cord serum Zn was observed |

| [80] | Cross-sectional | France | 510 (262 full-term + 248 preterm) | Serum | FAAS | - | Full-term: 1234 ± 202 Preterm: 1332 ± 248 | Cord blood Zn was higher in preterm than term infants, with no effect of gender. Zn levels decreased from 26 to 42 weeks of gestation, showing a negative biphasic pattern significantly associated with 26–34 weeks |

| [81] | Cross-sectional | Benin | 60 | Blood | ICP-MS | 5415 | 2276 | Zinc levels were significantly lower in cord than in maternal blood. |

| [48] | Prospective | Bangladesh | 745 | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 1209 | Zinc levels in cord blood were not associated with the risk of preterm birth. |

| [28] | Cross-sectional | Jakarta, Indonesia | 51 | Serum | ICP-MS | Term: 452 Preterm: 403 | Term: 2938 Preterm: 3214 | No differences in cord blood Zn levels between the preterm group (n = 26) and the group born at term (n = 25). |

| [83] | Case–control | NP | 43 cases with severe PE and 80 healthy pregnant women | Serum | ICP-MS | Cases: 685 ± 875 Cases: 534 ± 139 | Cases: 951 ± 230 Controls: 492 ± 135 | Zn levels were significantly higher in cord blood of the PE group than in the control group. Zn levels were not significantly different in maternal blood of the two groups. |

| [69] | Cross-sectional | Zabol, Iran | 60 | Serum | AAS | 684 ± 99 | 841 ± 110 | Serum Zn levels decreased significantly during pregnancy (1st to 3rd trimester) (749 ± 91 vs. 731 ± 106 vs. 684 ± 99 µg/L). Serum Zn levels in cord blood from normal birth weight infants were significantly higher than in cord blood from low birth weight infants. |

| [45] | Cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 44 | Plasma | ICP-MS | - | 3000 | Cord blood Zn levels were significantly and positively associated with birth weight (ρ = 0.35), chest circumference (ρ = 0.36), gestational age (ρ = 0.37), birth length (ρ = 0.39), and head circumference (ρ = 0.32). |

| [84] | Cross-sectional | Greater Poland region | 64 | Serum | F-AAS | 630 ± 170 | 650 ± 160 | Maternal serum Zn levels decreased significantly after delivery (460 ± 160 µg/L) compared with the period immediately before delivery (630 ± 170 µg/L). Cord serum Zn levels were significantly higher than maternal serum after delivery. |

| [85] | Cross-sectional | Gryfino, Poland | 136 | Blood | ICP-OES | 2940 ± 1100 | 1370 ± 570 | Maternal Zn levels were over 2-fold higher than those in cord blood (p < 0.05) and higher in women who smoked (4230 vs. 2950 μg/L). Cord Zn was positively associated with gestational age and negatively correlated with head circumference |

| [72] | Prospective cohort | NP | 68 | Serum | FEAS | 1360 ± 740 | 1570 ± 450 | Zn levels were lower in maternal (800 ± 300 μg/L) and cord serum (170 ± 0.430 μg/L) in premature infants with PPROM compared to those without PPROM (1360 ± 740 μg/L vs. 1570 ± 450 μg/L). |

| [51] | Prospective case–control | Israel | 80 | Plasma | ICP-MS | Active: 534 ± 139 Elective CD: 617 ± 266 | Active: 492 ± 135 Elective CD: 353 ± 120 | Significantly higher levels of Zn in cord blood during active labor compared to elective cesarean delivery (CD). |

| [86] | Cross-sectional | Ma’anshan, China | 3416 | Serum | ICP-MS | the 1st trimester: 1020 the 2nd trimester: 810 | 900 | No significant difference in Zn levels between maternal and cord blood. A significant difference in Zn levels between the two trimesters of pregnancy. |

| [49] | Case–control | Varanasi, India | 33 cases and 18 controls | Plasma | Spectrophotometry | - | 830 ± 88.5 | Zn levels were significantly lower in cord blood from PE (n = 19) (744 ± 150 µg/L) and eclampsia (n = 14) (677 ± 117 µg/L) than in the control group (830 ± 88.5 µg/L). |

| [87] | Cross-sectional | Terai, Nepal | 100 | Blood | ICP-MS | - | 2112 | Cord blood Zn levels were not associated with maternal age, socioeconomic status, living environment, and tobacco smoking. |

| [77] | Cross-sectional | Manhasset, New York, USA | 35 | Plasma | AAS | 625 ± 183 | 870 ± 95 | No significant differences in maternal plasma Zn levels depending on gestational age. Cord plasma Zn levels decreased with gestational age (from 24 to 42 weeks). |

| [35] | Cross-sectional | South Africa | 62 | Blood | ICP-MS | 6290 | 2548 | No correlation between maternal and cord blood Zn levels. |

| [26] | Prospective cohort | China | 1568 | Serum | AAS | 5521 ± 939 | - | Serum Zn remained stable across trimesters and compared to pre-pregnancy. Levels were significantly lower in cases of miscarriage, preterm labor, and premature rupture of membranes compared to controls. |

| [41] | Cross-sectional | Lucknow, India | 54 | Blood | FAAS | 5670 ± 2490 | 9460 ± 8350 | Women aged 24–28 had higher blood Zn than those aged 18–23. Maternal Zn was higher and cord Zn slightly lower in low birth weight infants, but not significantly. Maternal and cord Zn did not differ by gestational age |

| [107] | Cross-sectional | Zhejiang, China | 357 | Plasma | ICP-MS | - | 955 | Cord blood Zn levels were significantly higher in babies born in summer than in babies born in autumn/winter. |

| [39] | Cross-sectional | Serbia | 125 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 484 ± 145 | 356 ± 138 | A marginally significant difference in Zn levels between maternal blood and cord blood. A positive correlation between Zn levels in paired maternal and cord blood samples. |

| [90] | Longitudinal | Khoy, Iran | 162 | Serum | ICP-MS | 653 ± 149 | 854 ± 166 | Differences in Zn levels during the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters, 795 ± 150, 745 ± 161, and 653 ± 149 µg/L, respectively. About 42% of pregnant women were Zn deficient. Zn levels in cord serum were significantly higher than in maternal serum. |

| [21] | Case–control | Harran, Turkey | 144 | Serum | AAS | Cases: 836 ± 334 Controls: 1036 ± 300 | Cases: 1391 ± 504 Controls: 1294 ± 346 | Maternal serum Zn levels in the NTD group were significantly lower than in the control group. |

| [91] | Cross-sectional | Seville, Spain | 100 | Blood | ICP-MS | 5088 | 2221 | Zm levels in maternal blood were nearly three times higher than in cord blood (p < 0.05). Zn levels were positively correlated between maternal and cord blood. |

| [92] | Cross-sectional | Lublin, Poland | 134 | Blood | HR-ICP-OES | - | 2025 ± 718 | No significant correlations in Zn levels with anthropometric parameters. |

| [91] | Prospective cohort | Peking, China | 48 | Plasma | ICP-MS | 597 | 687 | No significant differences in plasma Zn levels during pregnancy (from the 1st to the 3rd trimester). Significantly higher Zn levels in cord plasma than in maternal plasma. |

| [93] | Prospective cohort | Norway | 211 | Blood | SF-ICP-MS | 5110 | - | Blood Zn levels increased significantly during pregnancy, 3 days postpartum, and 6 weeks postpartum. |

| [109] | Cross-sectional | Taipei, Taiwan | 308 | Serum | ICP-MS | - | 6192 ± 2508 | Maternal blood Zn levels reduce transplacental Pb transfer; a 10% increase in maternal blood Zn levels contributes to a 0.37 µg/L decrease in cord Pb levels. |

| [95] | Longitudinal | Shanghai, China | 100 | Blood (at 4 time points: preconception, GW 16, 24, and 32) | ICP-MS | 6060 ± 910 | 1940 ± 480 | Maternal blood Zn was higher before conception (5470 μg/L) than at 16 weeks (5070 μg/L) and remained relatively stable thereafter. Preconception Zn levels were correlated with levels at 24 weeks and with cord blood Zn |

| [43] | Case–control | Nottingham, England | 55 cases with PE, 60 healthy normotensive pregnant women, and 30 healthy non-pregnant women | Plasma | ICP-MS | 486 | 772 | Non-pregnant women (635 µg/L) had higher plasma Zn than normotensive pregnant women. Maternal Zn was lower in PE (418 µg/L) than controls (486 µg/L), with both early- and late-onset PE showing significant reductions. Cord plasma Zn was higher than maternal levels in both groups but did not differ between PE (830 µg/L) and controls (772 µg/L), nor by PE onset. Maternal Zn was positively correlated with birth weight. |

| [31] | Cross-sectional | Enugu Metropolis, Nigeria | 48 | Serum | AAS | 416 ± 24.5 | 427 ± 47.0 | Compared to the Zn reference ranges they found in the literature (660–1100 µg/L for maternal blood and >65 µg/dL for cord blood), the authors concluded that their study population had a Zn deficiency. |

| [30] | Case–control | Kermanshah province, Iran | 57 cases with diabetes and 54 controls | Serum | ICP-MS | Cases: 397 ± 531 Controls: 334 ± 694 | - | No significant differences in maternal Zn blood levels between cases and controls. |

| [59] | Case–control | Guangdong, China | 515 cases with PTB and 595 controls | Blood | ICP-MS | - | Cases: 1390 Controls: 1580 | Cord blood Zn levels were significantly lower in cases than in controls. Cord blood Zn levels were negatively associated with PTB. |

| [34] | Cross-sectional | Argentina | 696 | Blood | ICP-MS | 6682 | - | Blood Zn levels and parity were positively associated. Negative associations between blood Zn levels and birth weight, birth length, and head circumference. Maternal blood Zn levels were positively associated with gestational age in female children. |

| [22] | Cross-sectional | Isfahan, Iran | 263 | Blood (collected during the 1st trimester) | ICP-MS | 2518 ± 1484 | - | Blood Zn levels were positively associated with parity and, in female infants, with gestational age. Negative associations were observed with birth weight, length, and head circumference, though overall, Zn was not significantly linked to birth size outcomes |

| [95] | Retrospective | Guangzhou, China | 11,222 pregnant women and 545 non-pregnant women | Blood | ICP-MS | 5700 | - | Compared to non-pregnant women, Zn levels decreased during pregnancy. |

| [98] | Observational case–control | Istanbul, Turkey | 88 pregnant women (in their 3rd trimester) included 43 PE patients and 45 normotensive pregnant women as controls. | Serum | Spectrophotometry | 803 | - | No significant difference in Zn levels between PE women (751 ± 209 μg/L) and controls (803 ± 177 μg/L). |

| [29] | Case–control | Sudan | 50 PE and 50 healthy pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 1080 | - | No significant difference in Zn levels between PE women (1080 μg/L) and controls (1020 μg/L). |

| [100] | Case–control | Sanliurfa, Turkey | 24 women with PE and 44 women with normotensive pregnancies | Plasma | AAS | 11.93 ± 3.11 µg/g protein | - | Significantly higher Zn levels in PE group (15.53 ± 4.92 µg/g protein) than in controls (11.9 ± 3.11 µg/g protein). |

| [24] | Case–control | Nnewi, Nigeria | 54 cases with PE, 48 non-PE pregnant controls | Serum | AAS | 540 ± 39 | - | Levels of serum Zn in PE women (801 ± 119 µg/L) were significantly higher than in controls (540 ± 39 µg/L). |

| [100] | Case–control | Gorgan, Iran | 50 cases with PE and 50 healthy pregnant controls | Serum | AAS | 730 ± 330 | - | Zinc levels in PE women (710 ± 260 μg/L) were not significantly different than in controls (730 ± 330 μg/L). |

| [19] | Case–control | Bangladesh | 50 cases with PE and 58 normotensive pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 980 ± 30.0 | - | Levels of serum Zn in PE women (770 ± 50 μg/L) were significantly lower than in controls (980 ± 30 μg/L). |

| [110] | prospective cohort | Poznan, Poland | 121 with pregnancy-induced hypertension (10–14 gestational weeks) and 363 normotensive pregnant controls | Serum | ICP-MS | 615 | - | Levels of serum Cu in pregnant women with PIH (615 μg/L) were not significantly different from controls (615 μg/L). Serum Zn levels in the 10th–14th week of pregnancy were not associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension. |

| [27] | Cross-sectional | Guangdong Province, China | 97 with mild PE, 64 with severe PE, and 110 were normotensive healthy pregnant controls | Serum | ICP-MS | 5795 | Zn levels were lowest in the severe PE group (3956 μg/L), significantly below both the control (5795 μg/L) and mild PE (7502 μg/L) groups, while the mild PE group had significantly higher Zn than controls | |

| [96] | Cross sectional | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 44 PE women, 33 with eclampsia, and 27 normotensive pregnant women | Serum | AAS | 980 ± 130 | - | Serum Zn levels were significantly higher in PE (1044 ± 130 µg/L) than in eclampsia (914 ± 130 µg/L). Serum Zn levels in controls (980 ± 130 µg/L) did not differ compared to other groups. |