Biological Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Preservation Solution Ecosol in a Rat Liver Transplantation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

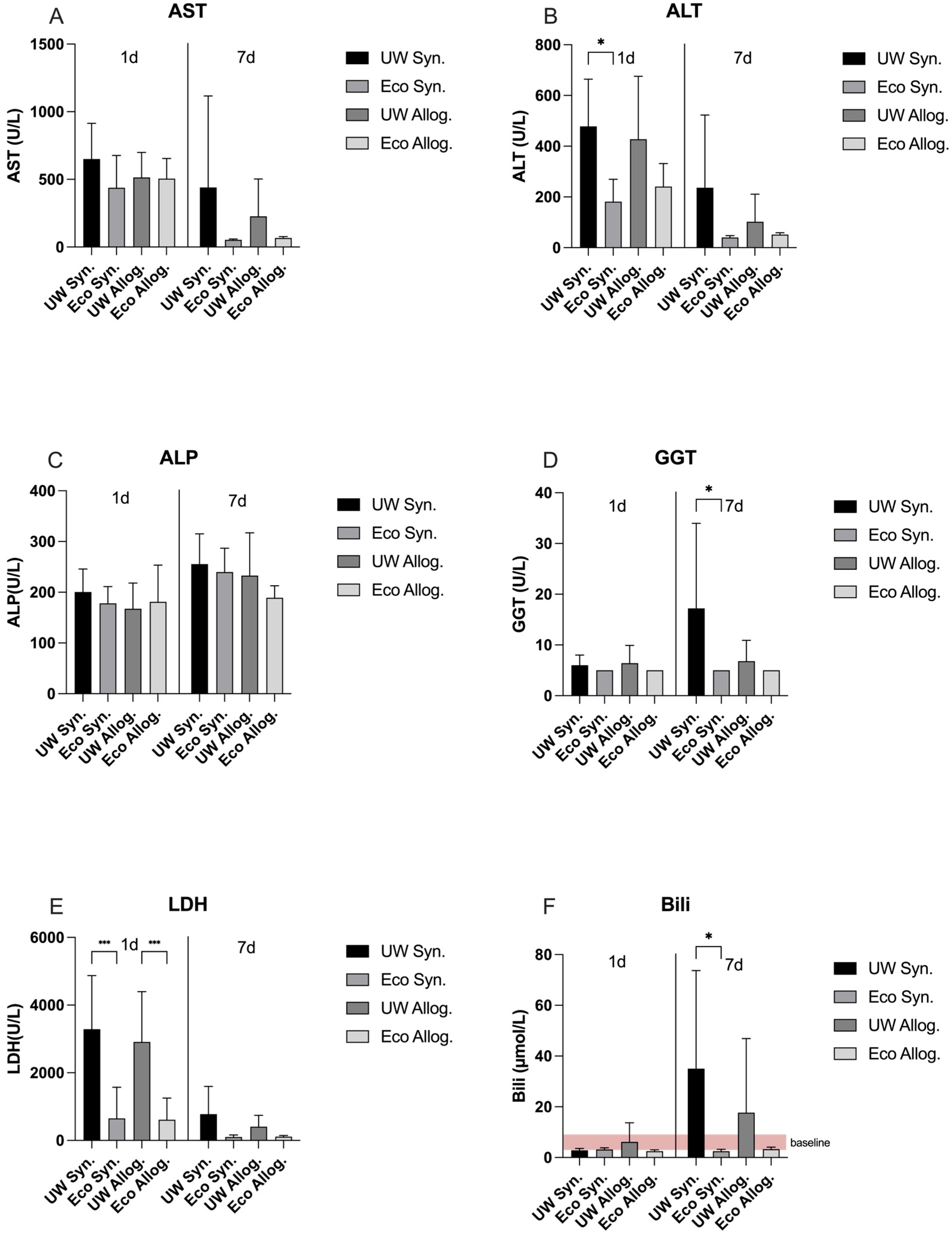

2.1. LDH and Liver Function Panel on Day 1 and Day 7 Post-Transplantation

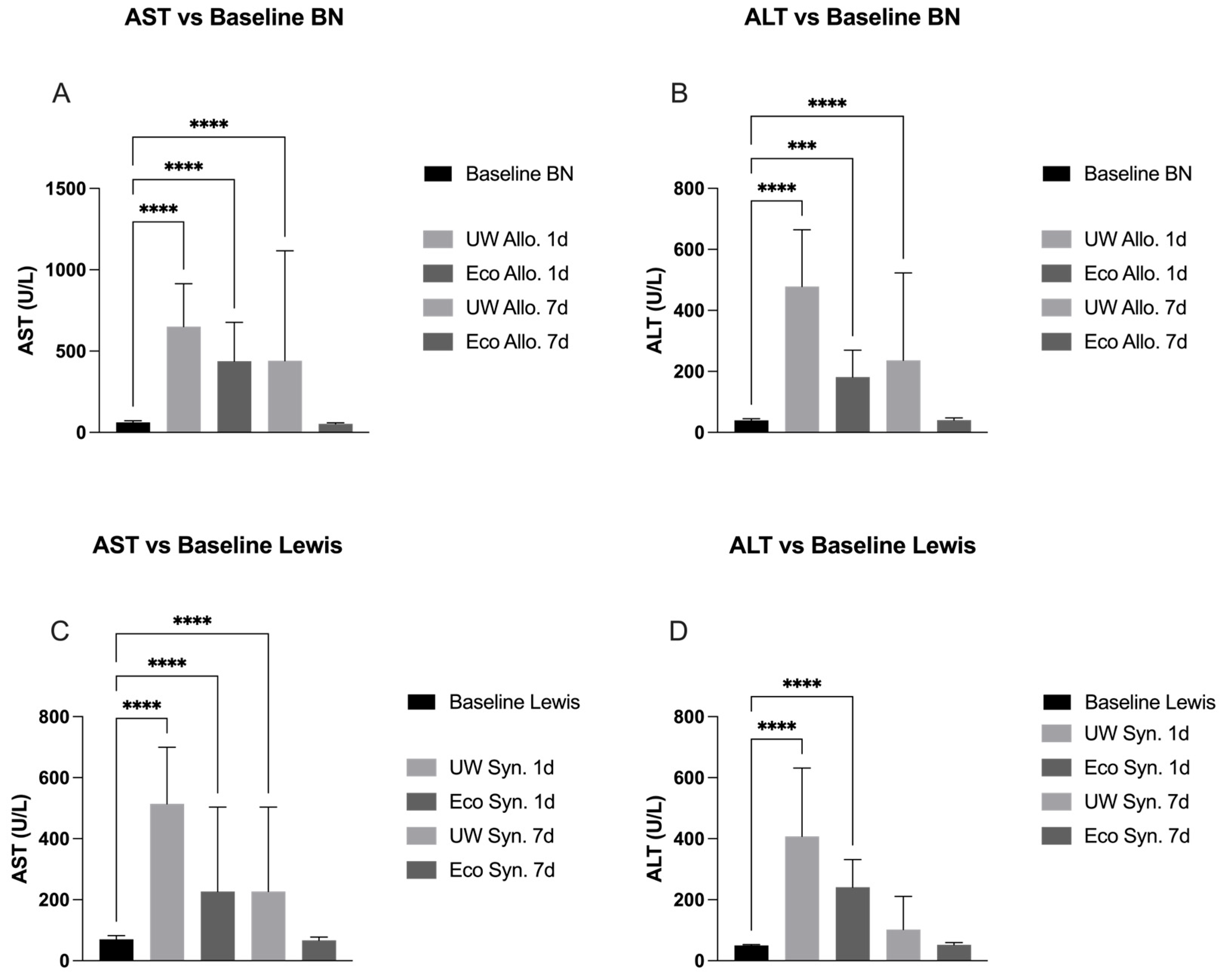

2.2. Liver Panel Compared to Baseline in Allogeneic Groups

2.3. Liver Panel Compared to Baseline in Syngeneic Groups

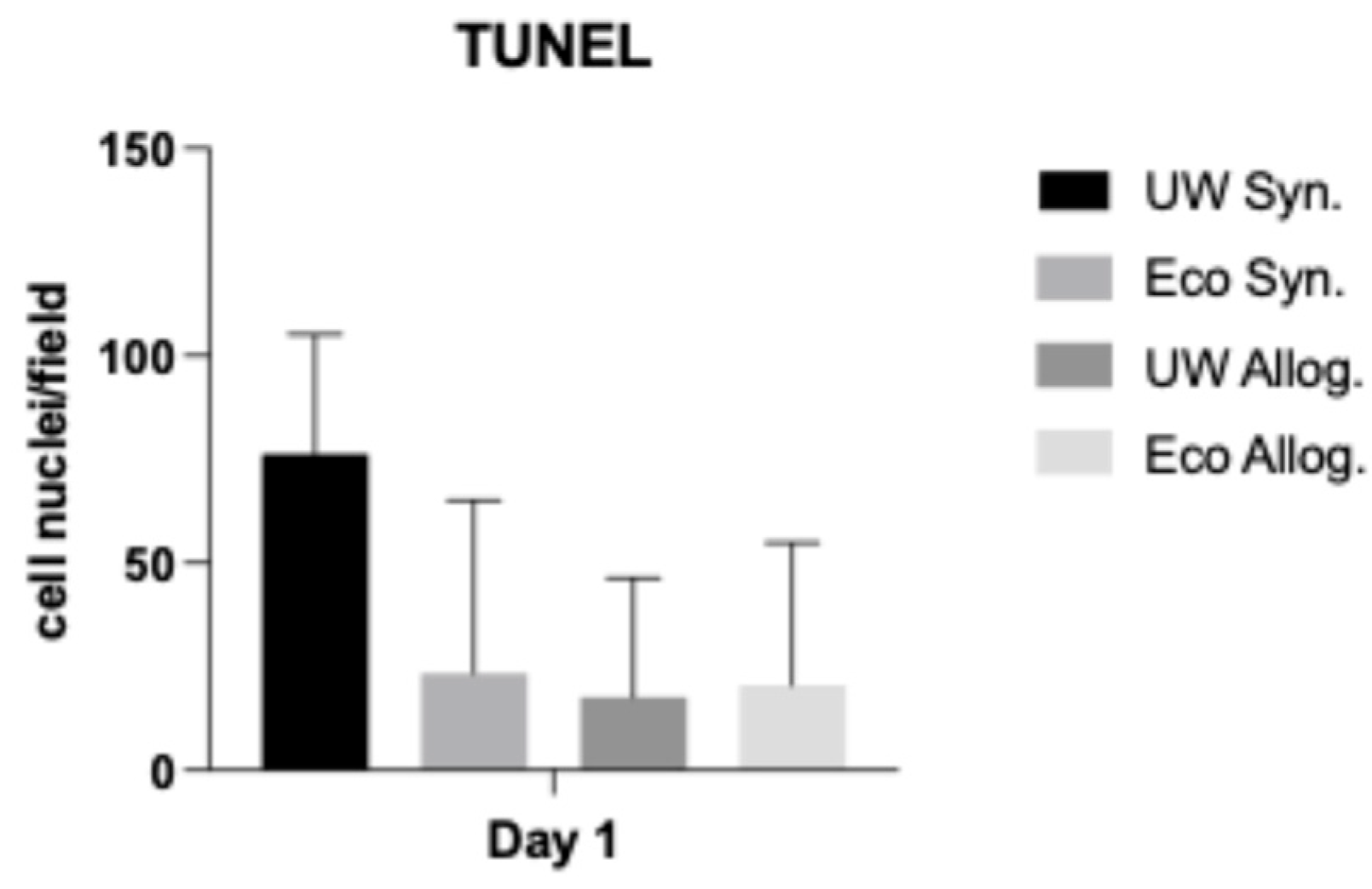

2.4. TUNEL Assay

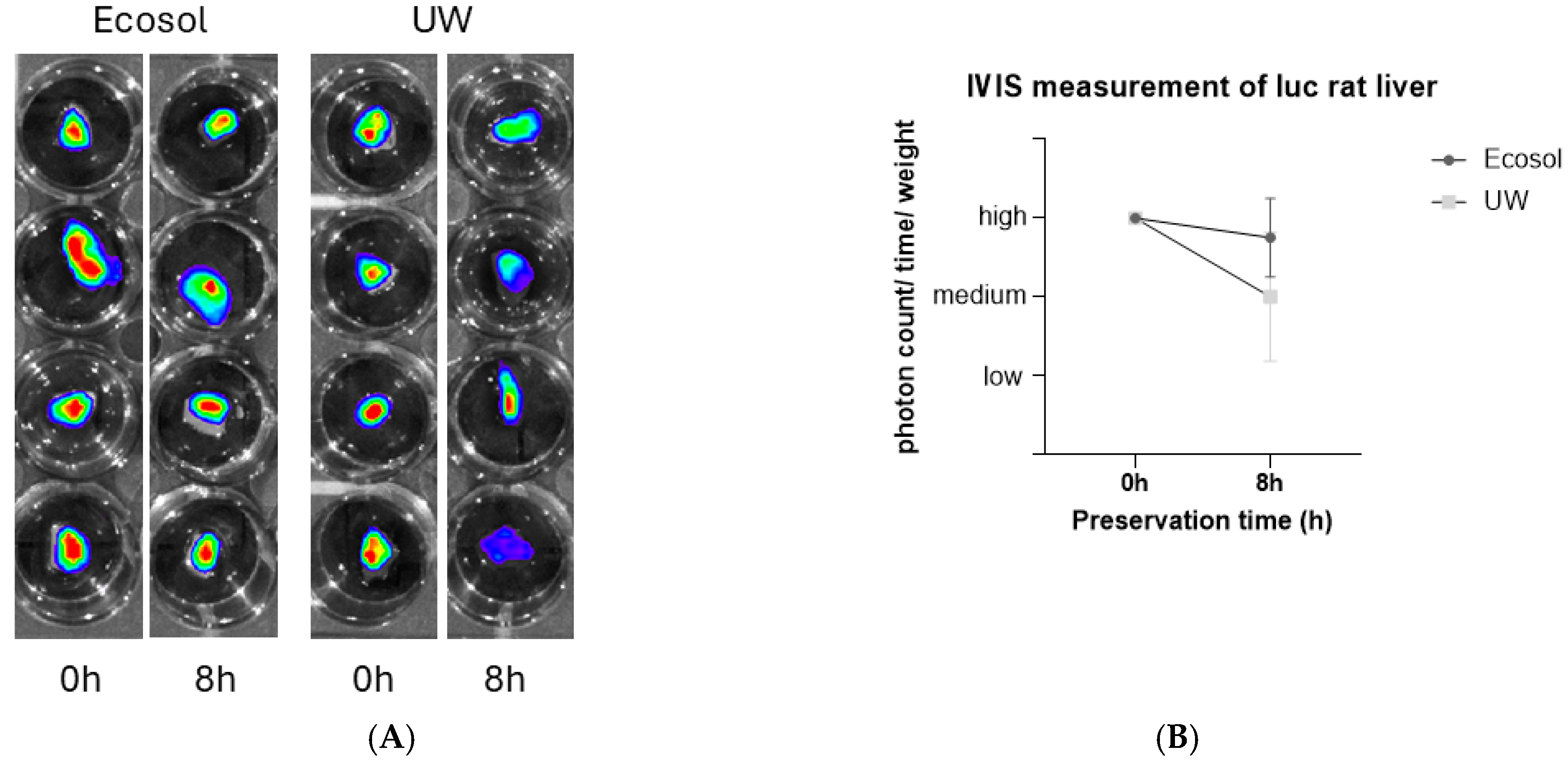

2.5. IVIS Imaging

3. Discussion

3.1. Preservation of the Bile Duct

3.2. Baseline Values

3.3. Graft Viability

3.4. Apoptotic Changes

3.5. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Experimental Procedure and Surgical Approach

4.3. Obtained Parameters

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rai, R. Liver Transplantatation—An Overview. Indian J. Surg. 2012, 75, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation Homepage. Available online: https://dso.de/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Braga, V.S.; Boteon, A.P.C.S.; Paglione, H.B.; Pecora, R.A.A.; Boteon, Y.L. Extended criteria brain-dead organ donors: Prevalence and impact on the utilisation of livers for transplantation in Brazil. World J. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Quaglia, A.; Gélat, P.; Saffari, N.; Rashidi, H.; Davidson, B. New Developments and Challenges in Liver Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isselhard, W. Stand und Gegenstand Chirurgischer Forschung. In Organkonservierung: Grundlagen, Entwicklungen, Perspek-Tiven; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Eckle, T. Ischemia and reperfusion—From mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southard, M.J.H.; Belzer, M.F.O. Organ Preservation. Annu. Rev. Med. 1995, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresa, C.D.L.; Nasralla, D.; Jassem, W. Normothermic Machine Preservation of the Liver: State of the Art. Curr. Transplant. Rep. 2018, 5, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, N.; Kobayashi, E. Challenges in machine perfusion preservation for liver grafts from donation after circulatory death. Transplant. Res. 2013, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchilikidi, K.Y. Liver graft preservation methods during cold ischemia phase and normothermic machine perfusion. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2019, 11, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.A.; Nicely, B.; Mattice, B.J.; Teaster, R. Comparative Analysis of Clinical Efficacy and Cost between University of Wisconsin Solution and Histidine-Tryptophan-Ketoglutarate. Prog. Transplant. 2008, 18, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, D.A.H.; Hübscher, S.G. Current views on rejection pathology in liver transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2010, 23, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, M.; Aktas, R.G.; Basdogan, C. Effect of solution and post-mortem time on mechanical and histological properties of liver during cold preservation. Biorheology 2014, 51, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenski, J.; Mancina, E.; Paschenda, P.; Beckers, C.; Bleilevens, C.; Tóthová, Ľ.; Boor, P.; Doorschodt, B.M.; Tolba, R.H. Improved Preservation of Warm Ischemia-Damaged Porcine Kidneys after Cold Storage in Ecosol, a Novel Preservation Solution. Ann. Transplant. 2015, 20, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.D.; Murad, K.L. Cellular Camouflage: Fooling the Immune System with Polymers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 1998, 4, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, M.; Peng, L.-P.; Liu, M. Organ preservation: From the past to the future. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer UW® Cold Storage Solution Instructions for Use|BTL’. Available online: https://bridgetolife.com/belzer-uw-cold-storage-solution-instructions/# (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Petrowsky, H.; Clavien, P.-A. Principles of liver preservation. In Transplantation of the Liver, 3rd ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibulesky, L.; Li, M.; Hansen, R.N.; Dick, A.A.; Montenovo, M.I.; Rayhill, S.C.; Bakthavatsalam, R.; Reyes, J.D. Impact of Cold Ischemia Time on Outcomes of Liver Transplantation: A Single Center Experience. Ann. Transplant. 2016, 21, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, M.; Cardini, B.; Peter, W.; Weissenbacher, A.; Oberhuber, R.; Hautz, T.; Otarashvili, G.; Margreiter, C.; Maglione, M.; Resch, T.; et al. Static cold storage compared with normothermic machine perfusion of the liver and effect on ischaemic-type biliary lesions after transplantation: A propensity score-matched study. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresa, C.D.; Nasralla, D.; Knight, S.; Friend, P.J. Cold storage or normothermic perfusion for liver transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2017, 22, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Z.A. UW Solution: Still the “Gold Standard” for Liver Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, G.; Parungao, J.M.; Hanouneh, I.A.; Parsi, M.A. Biliary complications following liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 2841–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Yin, J.; Xu, W.; Chai, F.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Effect of Different Bile Duct Flush Solutions on Biliary Tract Preservation Injury of Donated Livers for Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, J.; Teratani, T.; Kasahara, N.; Kikuchi, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Uemoto, S.; Kobayashi, E. Evaluation of Liver Preservation Solutions by Using Rats Transgenic for Luciferase. Transplant. Proc. 2014, 46, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eefting, F. Role of apoptosis in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 61, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahudeen, A.K.; Joshi, M.; Jenkins, J.K. Apoptosis Versus Necrosis During Cold Storage and Rewarming of Human Renal Proximal Tubular Cells. Transplantation 2001, 72, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnitz, L.; Doorschodt, B.M.; Ernst, L.; Hosseinnejad, A.; Edgworth, E.; Fechter, T.; Theißen, A.; Djudjaj, S.; Boor, P.; Rossaint, R.; et al. Taurine as Antioxidant in a Novel Cell- and Oxygen Carrier-Free Perfusate for Normothermic Machine Perfusion of Porcine Kidneys. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisello-Rosello, A.; Carbonell, T.; Rosello-Catafau, J.; Vengohechea, J.; Hessheimer, A.; Adam, R.; Fondevila, C. Static Cold Storage and Machine Perfusion: Redefining the Role of Preservation and Perfusate Solutions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/63/oj/eng (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- FELASA Working Group on Revision of Guidelines for Health Monitoring of Rodents and Rabbits; Mähler, M.; Berard, M.; Feinstein, R.; Gallagher, A.; Illgen-Wilcke, B.; Pritchett-Corning, K.; Raspa, M. FELASA recommendations for the health monitoring of mouse, rat, hamster, guinea pig and rabbit colonies in breeding and experimental units. Lab. Anim. 2014, 48, 178–192, Erratum in Lab. Anim. 2015, 49, 88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023677214550970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Sert, N.P.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzler, S.; Rix, A.; Czigany, Z.; Tanaka, H.; Fukushima, K.; Kögel, B.; Pawlowsky, K.; Tolba, R.H. Recommendation for severity assessment following liver resection and liver transplantation in rats: Part I. Lab. Anim. 2016, 50, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, J.D.; Kendale, S.M.; Jain, S.K.; Cuff, G.E.; Kim, J.T.; Rosenberg, A.D. Preoperative Evaluation Clinic Visit Is Associated with Decreased Risk of In-hospital Postoperative Mortality. Anesthesiology 2016, 125, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czigány, Z.; Iwasaki, J.; Yagi, S.; Nagai, K.; Szijártó, A.; Uemoto, S.; Tolba, R.H. Improving Research Practice in Rat Orthotopic and Partial Orthotopic Liver Transplantation: A Review, Recommendation, and Publication Guide. Eur. Surg. Res. 2015, 55, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czigany, Z.; Bleilevens, C.; Beckers, C.; Stoppe, C.; Möhring, M.; Fülöp, A.; Szijarto, A.; Lurje, G.; Neumann, U.P.; Tolba, R.H. Limb remote ischemic conditioning of the recipient protects the liver in a rat model of arterialized orthotopic liver transplantation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, K.; Yagi, S.; Uemoto, S.; Tolba, R.H. Surgical Procedures for a Rat Model of Partial Orthotopic Liver Transplantation with Hepatic Arterial Reconstruction. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 73, e4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Ingredients | Ecosol | UW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colloid Impermeants Buffers | PEG 35,000 | 5.4 | - |

| HAES 5% | - | 50 g/L | |

| Sodium gluconate | 37.1 | - | |

| Magnesium gluconate/sulfate | 12.0 | 1.23 g/L | |

| Calcium gluconate | 2.3 | - | |

| Lactobionic acid | 12.0 | 35.8 g/L | |

| Trehalose | 4.0 | - | |

| Raffinose | 1.7 | 17.8 g/L | |

| HEPES | 16.8 | - | |

| Histidine | 10.0 | - | |

| Potassium phosphate | 2.2 | 3.4 g/L | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 2.2 | - | |

| Sodium citrate | 3.1 | - | |

| Potassium hydroxide | - | 5.6 g/L | |

| Antioxidants Energy substrates | Taurine | 36.8 | - |

| Glutathion | 12.0 | 0.9 g/L | |

| Allopurinol | - | 0.1 g/L | |

| Glucose | 6.9 | - | |

| Pyruvate | 1.8 | - | |

| Adenosine | 6.0 | 1.3 g/L | |

| Amino acids | Tryptophan, Arginine, Carnitine, Cysteine, Glutamic acid, Glutamine, Glycine, Ornithine | Yes | No |

| Vitamins | Ascorbic acid, Biotin | Yes | No |

| Electrolytes | Na+/K+ | 124/12 | 29/125 |

| Viscosity | at approximately room temperature | 2.2 c.P. | 5.7 c.P. |

| Osmolarity | 310 mOsmol/L | 320 mOsmol/L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yildirim, K.; Tanaka, H.; Doorschodt, B.M.; Fukushima, K.; Yagi, S.; Oldhafer, F.; Beetz, O.; Bleilevens, C.; Czigany, Z.; Tolba, R.H. Biological Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Preservation Solution Ecosol in a Rat Liver Transplantation Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010144

Yildirim K, Tanaka H, Doorschodt BM, Fukushima K, Yagi S, Oldhafer F, Beetz O, Bleilevens C, Czigany Z, Tolba RH. Biological Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Preservation Solution Ecosol in a Rat Liver Transplantation Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleYildirim, Kerim, Hirokazu Tanaka, Benedict M. Doorschodt, Kenji Fukushima, Shintaro Yagi, Felix Oldhafer, Oliver Beetz, Christian Bleilevens, Zoltan Czigany, and Rene H. Tolba. 2026. "Biological Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Preservation Solution Ecosol in a Rat Liver Transplantation Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010144

APA StyleYildirim, K., Tanaka, H., Doorschodt, B. M., Fukushima, K., Yagi, S., Oldhafer, F., Beetz, O., Bleilevens, C., Czigany, Z., & Tolba, R. H. (2026). Biological Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Preservation Solution Ecosol in a Rat Liver Transplantation Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010144