Immune Delay, Beyond Immune Evasion, as a Driver of Pathogen Propagation Competence Through Neutrophil Dysregulation, to be Mitigated by Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (LF-EMF)

Abstract

1. Immune Evasion

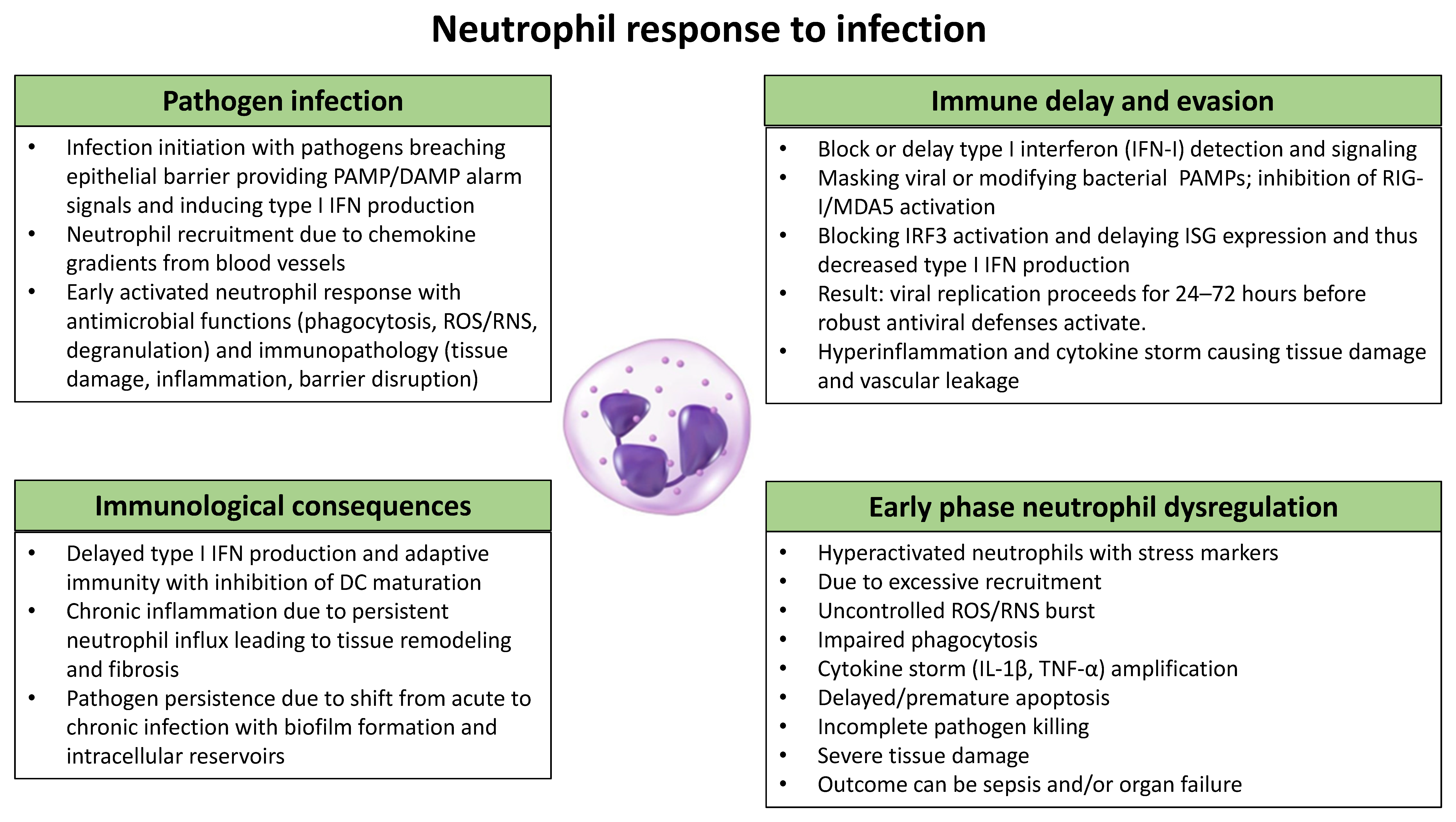

2. Immune Delay During Infection

3. Neutrophils in the Innate Immune Response

3.1. Neutrophil Migration

3.2. Infection Recognition

3.3. Neutrophil Activation and Effector Functions

3.4. Death of Neutrophils

3.5. Connecting Innate to Adaptive Immune Responses

4. Neutrophils in Infection-Induced Evasion and Immune Delay

4.1. Virus-Induced Type I Interferon Response

4.2. Bacterial Induced Type I Interferon Response

5. Dysregulated Neutrophils in Infectious Diseases

5.1. Dysregulation Resulting in Immune Evasion

5.2. Aberrant Neutrophil-Based Innate Immune Responses

6. Electromagnetic Fields (EMFs) and Neutrophil Activation

6.1. Biological Effects of LF-EMF Exposure

6.2. Neutrophils and LF-EMF Exposure

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Finlay, B.B.; McFadden, G. Anti-immunology: Evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell 2006, 124, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, A.G.; Unterholzner, L. Viral evasion and subversion of pattern-recognition receptor signaling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Chevillotte, M.D.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.J.; Phillips, R.E. Escape of human immunodeficiency virus from immune control. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, P.D.; Mascola, J.R.; Nabel, G.J. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and the search for an HIV-1 vaccine: The end of the beginning. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, M.D.; Malik, H.S. Rules of engagement: Molecular insights from host-virus arms races. Annu. Rev. Gen. 2012, 46, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, R.E.; Isberg, R.R.; Portnoy, D.A. Patterns of Pathogenesis: Discrimination of Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Microbes by the Innate Immune System. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäumler, A.J.; Sperandio, V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature 2016, 535, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambris, J.D.; Ricklin, D.; Geisbrecht, B.V. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Microbiol. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucy, S.M.; Huang, J.; Gogarten, J.P. Horizontal gene transfer: Building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Gen. 2015, 16, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, B.H.; Bhatt, A.S.; McDonald, M.J. Unraveling the tempo and mode of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Microbiol. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, P.F.; Würzner, R.; Skerka, C. Complement evasion of pathogens: Common strategies are shared by diverse organisms. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 3850–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, P.F.; Hallström, T.; Riesbeck, K. Human complement control and complement evasion by pathogenic microbes—Tipping the balance. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 56, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, E.; Medzhitov, R. Recognition of microbial infection by Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003, 15, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, N.M.; Dehaven, B.C.; Xiao, Y.; Alexander, E.; Viner, K.M.; Isaacs, S.N. The Vaccinia virus complement control protein modulates adaptive immune responses during infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenten, D.; Medzhitov, R. The control of adaptive immune responses by the innate immune system. Adv. Immunol. 2011, 109, 87–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploegh, H.L. Viral strategies of immune evasion. Science 1998, 280, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beachboard, D.C.; Horner, S.M. Innate immune evasion strategies of DNA and RNA viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 32, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensterl, V.; Sen, G.C. Interferons and viral infections. BioFactors 2009, 35, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.T.; Sullivan, B.M.; Teijaro, J.R.; Lee, A.M.; Welch, M.; Rice, S.; Sheehan, K.C.F.; Schreiber, R.D.; Oldstone, M.B.A. Blockade of interferon Beta, but not interferon alpha, signaling controls persistent viral infection. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenne, C.N.; Wong, C.H.Y.; Zemp, F.J.; McDonald, B.; Rahman, M.M.; Forsyth, P.A.; McFadden, G.; Kubes, P. Neutrophils recruited to sites of infection protect from virus challenge by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pall, M.L. Electromagnetic fields act via activation of voltage-gated calcium channels to produce beneficial or adverse effects. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2013, 17, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simko, M. Cell Type Specific Redox Status is Responsible for Diverse Electromagnetic Field Effects. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, A.L.; White, N.C.; Litovitz, T.A. Mechanical and electromagnetic induction of protection against oxidative stress. Bioelectrochemistry 2001, 53, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O’Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecchio, C.; Cassatella, M.A. Neutrophil-derived chemokines on the road to immunity. Sem. Immunol. 2016, 28, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashkiv, L.B.; Donlin, L.T. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkó, M.; Mattsson, M.-O. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields as effectors of cellular responses in vitro: Possible immune cell activation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 93, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiermann, C.; Kunisaki, Y.; Frenette, P.S. Circadian control of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzella, N.; Bracci, M.; Ciarapica, V.; Staffolani, S.; Strafella, E.; Rapisarda, V.; Valentino, M.; Amati, M.; Copertaro, A.; Santarelli, L. Circadian gene expression and extremely low-frequency magnetic fields: An in vitro study. Bioelectromagnetics 2015, 36, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartenstein, V. Blood cells and blood cell development in the animal kingdom. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. 2006, 22, 677–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.D.; Malachowa, N.; DeLeo, F.R. Influence of Microbes on Neutrophil Life and Death. Microbiol. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.D.; DeLeo, F.R. Role of neutrophils in innate immunity: A systems biology-level approach. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2009, 1, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Schlitzer, A.; Placek, K.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Schultze, J.L. Innate and Adaptive Immune Memory: An Evolutionary Continuum in the Host’s Response to Pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masenga, S.K.; Mweene, B.C.; Luwaya, E.; Muchaili, L.; Chona, M.; Kirabo, A. HIV–Host Cell Interactions. Cells 2023, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Negrate, G. Viral interference with innate immunity by preventing NF-κB activity. Microbiol. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkert, M. Innate Immune Evasion by Human Respiratory RNA Viruses. J. Innate Immun. 2020, 12, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Vidyarthi, A.; Javed, S.; Agrewala, J.N. Innate Immunity Holding the Flanks until Reinforced by Adaptive Immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, P.D.; Hunstad, D.A. Subversion of Host Innate Immunity by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Pathogens 2016, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, M.; Askarian, F.; Sangvik, M.; Sollid, J.E. Bacterial interference with canonical NFκB signalling. Microbiology 2013, 159, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askarian, F.; Wagner, T.; Johannessen, M.; Nizet, V. Staphylococcus aureus modulation of innate immune responses through Toll-like (TLR), (NOD)-like (NLR) and C-type lectin (CLR) receptors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Alsenani, Q.; Lanz, M.; Birchall, C.; Drage, L.K.L.; Picton, D.; Mowbray, C.; Ali, A.; Harding, C.; Pickard, R.S.; et al. Evasion of toll-like receptor recognition by Escherichia coli is mediated via population level regulation of flagellin production. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1093922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triboulet, S.; Subtil, A. Make It a Sweet Home: Responses of Chlamydia trachomatis to the Challenges of an Intravacuolar Lifestyle. Microbiol. Spectrum 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, N.J.; Zwack, E.E.; Brodsky, I.E. Activation and evasion of inflammasomes by Yersinia. In Inflammasome Signalling and Bacterial Infections; Backert, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pamer, E.G. Immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, D.C.; Kulkarni, R.R.; Shewen, P.E. Subversion of the Immune Response by Bacterial Pathogens. In Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infections in Animals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, G.R. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop “type III” weaponry. Mol. Cell Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodsky, I.E.; Palm, N.W.; Sadanand, S.; Ryndak, M.B.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Flavell, R.A.; Bliska, J.B.; Medzhitov, R. A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashida, H.; Mimuro, H.; Sasakawa, C. Shigella manipulates host immune responses by delivering effector proteins with specific roles. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaan, A.N.; Surewaard, B.G.J.; Nijland, R.; van Strijp, J.A.G. Neutrophils versus Staphylococcus aureus: A biological tug of war. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; van Strijp, J.A.G. Bacterial complement evasion. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sastre, A. Inhibition of interferon-mediated antiviral responses by influenza A viruses and other negative-strand RNA viruses. Virology 2001, 279, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Horvath, C.M. Paramyxovirus disruption of interferon signal transduction: STATus report. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009, 29, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Dong, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, W.; Xiao, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Ren, L.; et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericksen, B.L.; Keller, B.C.; Fornek, J.; Katze, M.G.; Gale, M. Establishment and maintenance of the innate antiviral response to West Nile Virus involves both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling through IPS-1. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, S.; Torensma, R. Another look at the life of a neutrophil. World J. Hematol. 2013, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenderman, L.; Vrisekoop, N. Extramedullary neutrophil progenitors: Quo Vadis? Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, D.; Maslovarić, I.; Djikić, D.; Čokić, V.P. Neutrophil Death in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Shedding More Light on Neutrophils as a Pathogenic Link to Chronic Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eash, K.J.; Greenbaum, A.M.; Gopalan, P.K.; Link, D.C. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourshargh, S.; Alon, R. Leukocyte migration into inflamed tissues. Immunity 2014, 41, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Burdon, P.C.E.; Bridger, G.; Gutierrez-Ramos, J.C.; Williams, T.J.; Rankin, S.M. Chemokines acting via CXCR2 and CXCR4 control the release of neutrophils from the bone marrow and their return following senescence. Immunity 2003, 19, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, T.; Mócsai, A. Feedback Amplification of Neutrophil Function. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, A.; Bosio, E.; Stone, S.F.; Fatovich, D.M.; Arendts, G.; MacDonald, S.P.J.; Burrows, S.; Brown, S.G.A. Markers Involved in Innate Immunity and Neutrophil Activation are Elevated during Acute Human Anaphylaxis: Validation of a Microarray Study. J. Innate Immun. 2019, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshaber-Bouyer, R.; Nigrovic, P.A. Neutrophil Heterogeneity as Therapeutic Opportunity in Immune-Mediated Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersson, G.; Phillipson, M. The neutrophil: One cell on many missions or many cells with different agendas? Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollberger, G.; Brenes, A.J.; Warner, J.; Arthur, J.S.C.; Howden, A.J.M. Quantitative proteomics reveals tissue-specific, infection-induced and species-specific neutrophil protein signatures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strydom, N.; Rankin, S.M. Regulation of circulating neutrophil numbers under homeostasis and in disease. J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, C.; Rankin, S.M.; Condliffe, A.M.; Singh, N.; Peters, A.M.; Chilvers, E.R. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 2010, 31, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, K.; Kaisho, T.; Akira, S. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 335–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, Y.-M.; Gale, M. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity 2011, 34, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, D.J.; Girardin, S.E. Nod-like receptors: Sentinels at host membranes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes. Cell 2010, 140, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayadas, T.N.; Cullere, X.; Lowell, C.A. The multifaceted functions of neutrophils. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2014, 9, 181–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklin, D.; Hajishengallis, G.; Yang, K.; Lambris, J.D. Complement: A key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis e Sousa, C.; Yamasaki, S.; Brown, G.D. Myeloid C-type lectin receptors in innate immune recognition. Immunity 2024, 57, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, S.; Hafkamp, F.M.J.; Varela, L.; Simkhada, N.; Taanman-Kueter, E.W.; Tas, S.W.; Wauben, M.H.M.; Groot Kormelink, T.; de Jong, E.C. Efficient Neutrophil Activation Requires Two Simultaneous Activating Stimuli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauseef, W.M.; Borregaard, N. Neutrophils at work. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P. Mechanisms of degranulation in neutrophils. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2006, 2, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A Cell with Many Roles in Inflammation or Several Cell Types? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, G.L.; Foti, A.; Marsman, G.; Patel, D.F.; Zychlinsky, A. The Neutrophil. Immunity 2021, 54, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollberger, G.; Tilley, D.O.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: The Biology of Chromatin Externalization. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borregaard, N.; Herlin, T. Energy metabolism of human neutrophils during phagocytosis. J. Clin. Investig. 1982, 70, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Roig, C.; Fridlender, Z.G.; Glogauer, M.; Scapini, P. Neutrophil Diversity in Health and Disease. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, A.; Khan, J.A.; Alkachem, A.Y.; Sabur, H.; Alkattan, K.; Yaqinuddin, A.; Sing, G.K. How Neutrophils Shape the Immune Response: Reassessing Their Multifaceted Role in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, D.L.; Henson, P.M. Neutrophil clearance: When the party is over, clean-up begins. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweet, M.J.; Ramnath, D.; Singhal, A.; Kapetanovic, R. Inducible antibacterial responses in macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Phagocytosis: Our Current Understanding of a Universal Biological Process. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, S.B.; Miao, E.A. Gasdermins: Effectors of Pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yipp, B.G.; Petri, B.; Salina, D.; Jenne, C.N.; Scott, B.N.V.; Zbytnuik, L.D.; Pittman, K.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Wu, K.; Meijndert, H.C.; et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilsczek, F.H.; Salina, D.; Poon, K.K.H.; Fahey, C.; Yipp, B.G.; Sibley, C.D.; Robbins, S.M.; Green, F.H.Y.; Surette, M.G.; Sugai, M.; et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remijsen, Q.; Berghe, T.V.; Wirawan, E.; Asselbergh, B.; Parthoens, E.; De Rycke, R.; Noppen, S.; Delforge, M.; Willems, J.; Vandenabeele, P. Neutrophil extracellular trap cell death requires both autophagy and superoxide generation. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, N.V.; Chernyak, B.V. NETosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Role in Physiology and Pathology. Biochem. Biokhimiia 2020, 85, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.; Micheletti, A.; Cassatella, M.A. Modulation of human neutrophil survival and antigen expression by activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 88, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, C.; Demaurex, N.; Lowell, C.A.; Uribe-Querol, E. Neutrophils: Their Role in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 1469780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauvillain, C.; Delneste, Y.; Scotet, M.; Peres, A.; Gascan, H.; Guermonprez, P.; Barnaba, V.; Jeannin, P. Neutrophils efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo. Blood 2007, 110, 2965–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi Abdallah, D.S.; Egan, C.E.; Butcher, B.A.; Denkers, E.Y. Mouse neutrophils are professional antigen-presenting cells programmed to instruct Th1 and Th17 T-cell differentiation. Int. Immunol. 2011, 23, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, A.; Gwyer Findlay, E. Evidence for antigen presentation by human neutrophils. Blood 2024, 143, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vono, M.; Lin, A.; Norrby-Teglund, A.; Koup, R.A.; Liang, F.; Loré, K. Neutrophils acquire the capacity for antigen presentation to memory CD4+ T cells in vitro and ex vivo. Blood 2017, 129, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzk, N.; Papayannopoulos, V. Molecular mechanisms regulating NETosis in infection and disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, I.; Cols, M.; Barra, C.M.; He, B.; Cassis, L.; Gentile, M.; Comerma, L.; Chorny, A.; Shan, M.; Xu, W.; et al. B cell–helper neutrophils stimulate the diversification and production of immunoglobulin in the marginal zone of the spleen. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliefeld, P.H.C.; Wessels, C.M.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Koenderman, L.; Pillay, J. The role of neutrophils in immune dysfunction during severe inflammation. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Carrillo, J.L.; Castro García, F.P.; Coronado, O.G.; Moreno García, M.A.; Contreras Cordero, J.F. Physiology and Pathology of Innate Immune Response Against Pathogens. In Physiology and Pathology of Immunology; Rezaei, N., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and Distinct Functions of Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, N.G.; Alfajaro, M.M.; Gasque, V.; Huston, N.C.; Wan, H.; Szigeti-Buck, K.; Yasumoto, Y.; Greaney, A.M.; Habet, V.; Chow, R.D.; et al. Single-cell longitudinal analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in human airway epithelium identifies target cells, alterations in gene expression, and cell state changes. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Liu, W.-C.; Uhl, S.; Hoagland, D.; Møller, R.; Jordan, T.X.; Oishi, K.; Panis, M.; Sachs, D.; et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell 2020, 181, 1036–1045.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Sancho, L.; Lewinski, M.K.; Pache, L.; Stoneham, C.A.; Yin, X.; Becker, M.E.; Pratt, D.; Churas, C.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Liu, S.; et al. Functional landscape of SARS-CoV-2 cellular restriction. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2656–2668.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermesh, T.; Moltedo, B.; López, C.B.; Moran, T.M. Buying time-the immune system determinants of the incubation period to respiratory viruses. Viruses 2010, 2, 2541–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severa, M.; Diotti, R.A.; Etna, M.P.; Rizzo, F.; Fiore, S.; Ricci, D.; Iannetta, M.; Sinigaglia, A.; Lodi, A.; Mancini, N.; et al. Differential plasmacytoid dendritic cell phenotype and type I Interferon response in asymptomatic and severe COVID-19 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wu, J.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.-J.; Chen, J. Disease-Associated Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.A.; Sy, S.; Galen, B.; Goldstein, D.Y.; Orner, E.; Keller, M.J.; Herold, K.C.; Herold, B.C. Natural mucosal barriers and COVID-19 in children. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e148694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paget, C.; Doz-Deblauwe, E.; Winter, N.; Briard, B. Specific NLRP3 Inflammasome Assembling and Regulation in Neutrophils: Relevance in Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pylaeva, E.; Lang, S.; Jablonska, J. The Essential Role of Type I Interferons in Differentiation and Activation of Tumor-Associated Neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loske, J.; Röhmel, J.; Lukassen, S.; Stricker, S.; Magalhães, V.G.; Liebig, J.; Chua, R.L.; Thürmann, L.; Messingschlager, M.; Seegebarth, A.; et al. Pre-activated antiviral innate immunity in the upper airways controls early SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Thomas, P.G.; Randolph, A.G. Immunology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjadj, J.; Yatim, N.; Barnabei, L.; Corneau, A.; Boussier, J.; Smith, N.; Péré, H.; Charbit, B.; Bondet, V.; Chenevier-Gobeaux, C.; et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science 2020, 369, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feld, J.J.; Kandel, C.; Biondi, M.J.; A Kozak, R.; Zahoor, M.A.; Lemieux, C.; Borgia, S.M.; Boggild, A.K.; Powis, J.; McCready, J.; et al. Peginterferon lambda for the treatment of outpatients with COVID-19: A phase 2, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Resp. Med. 2021, 9, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.-E.; Rovina, N.; Lampropoulou, V.; Triantafyllia, V.; Manioudaki, M.; Pavlos, E.; Koukaki, E.; Fragkou, P.C.; Panou, V.; Rapti, V.; et al. Untuned antiviral immunity in COVID-19 revealed by temporal type I/III interferon patterns and flu comparison. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Hou, Z.; Liu, F.; Song, P.; Qiu, F.; Wang, X.; Zou, X.; Wan, D.; et al. Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study Shows Early Interferon Therapy Is Associated with Favorable Clinical Responses in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 455–464.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbach, L.A.; Scheer, M.H.; Cuppen, J.J.M.; Savelkoul, H.; Verburg-van Kemenade, B.M.L. Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Field Exposure Enhances Extracellular Trap Formation by Human Neutrophils through the NADPH Pathway. J. Innate Immun. 2015, 7, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, J.J.M.; Gradinaru, C.; Raap-van Sleuwen, B.E.; de Wit, A.C.E.; van der Vegt, T.A.A.J.; Savelkoul, H.F.J. LF-EMF Compound Block Type Signal Activates Human Neutrophilic Granulocytes In Vivo. Bioelectromagnetics 2022, 43, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Fehr, A.R.; Zheng, J.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Abrahante, J.E.; Mack, M.; Sompallae, R.; McCray, P.B.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. IFN-I response timing relative to virus replication determines MERS coronavirus infection outcomes. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.N.; Miao, Y. The nature of immune responses to urinary tract infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herant, M.; Marganski, W.A.; Dembo, M. The mechanics of neutrophils: Synthetic modeling of three experiments. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 3389–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herant, M.; Heinrich, V.; Dembo, M. Mechanics of neutrophil phagocytosis: Experiments and quantitative models. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesaitis, A.J.; Franklin, M.J.; Berglund, D.; Sasaki, M.; Lord, C.I.; Bleazard, J.B.; Duffy, J.E.; Beyenal, H.; Lewandowski, Z. Compromised host defense on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: Characterization of neutrophil and biofilm interactions. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 4329–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poll, T.; Marchant, A.; Keogh, C.V.; Goldman, M.; Lowry, S.F. Interleukin-10 impairs host defense in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 174, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, B.; Sohn, S. Neutrophils in Inflammatory Diseases: Unraveling the Impact of Their Derived Molecules and Heterogeneity. Cells 2023, 12, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monem, S.; Furmanek-Blaszk, B.; Łupkowska, A.; Kuczynska-Wisnik, D.; Stojowska-Swedrzynska, K.; LaskowskaInt, E. Mechanisms Protecting Acinetobacter baumannii against Multiple Stresses Triggered by the Host Immune Response, Antibiotics and Outside-Host Environment. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, S.; Chambers, J.P.; Yu, J.-J.; Hung, C.-Y.; Forsthuber, T.; Arulanandam, B.P. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii protective immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1070424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbim, C.; Katsikis, P.D.; Estaquier, J. Neutrophil apoptosis during viral infections. Open Virol. J. 2009, 3, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamone, G.V.; Petracca, Y.; Fuxman Bass, J.I.; Rumbo, M.; Nahmod, K.A.; Gabelloni, M.L.; Vermeulen, M.E.; Matteo, M.J.; Geffner, J.R.; Trevani, A.S. Flagellin delays spontaneous human neutrophil apoptosis. Lab. Investig. 2010, 90, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.D.; Braughton, K.R.; Whitney, A.R.; Voyich, J.M.; Schwan, T.G.; Musser, J.M.; DeLeo, F.R. Bacterial pathogens modulate an apoptosis differentiation program in human neutrophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10948–10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L.; Muller, H.S.; Martins, V.d.P. Unweaving the NET: Microbial strategies for neutrophil extracellular trap evasion. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 171, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz, A.A.; Hao, H.; Lan, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Chu, Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps in bacterial infections and evasion strategies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1357967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.D.; Malachowa, N.; DeLeo, F.R. Neutrophils and Bacterial Immune Evasion. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, C.F.; Lourido, S.; Zychlinsky, A. How do microbes evade neutrophil killing? Microbiol. Cell. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönrich, G.; Raftery, M.J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Go Viral. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; He, R.; Luo, J.; Yan, S.; Zhu, W.; Liu, S. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Viral Infections. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, C.; Kirsebom, F.C.M. Neutrophils in respiratory viral infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Vrati, S.; Banerjee, A. Neutrophils at the crossroads of acute viral infections and severity. Mol. Asp. Med. 2021, 81, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, P.; Saffarzadeh, M.; Weber, A.N.R.; Rieber, N.; Radsak, M.; von Bernuth, H.; Benarafa, C.; Roos, D.; Skokowa, J.; Hartl, D. Neutrophils: Between host defence, immune modulation, and tissue injury. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xia, Y.; Su, J.; Quan, F.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Lin, C.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Z. Neutrophil diversity and function in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.-D.; Ji, T.-T.; Dong, J.-R.; Feng, H.; Chen, F.-Q.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Chen, D.-K.; Ma, W.-T. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Cytokine Storm Induced by Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Alipoor, S.D.; Adcock, I.M.; Mumby, S.; Koenderman, L. Update on Neutrophil Function in Severe Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, T.; Uehara, T.; Matsumoto, G.; Arai, S.; Sugano, M. Neutrophil left shift and white blood cell count as markers of bacterial infection. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 457, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimo, G.; Xu, W.; Kwok, I.; Abdad, M.Y.; Chan, Y.-H.; Fong, S.-W.; Puan, K.J.; Lee, C.Y.-P.; Yeo, N.K.-W.; Amrun, S.N.; et al. Whole blood immunophenotyping uncovers immature neutrophil-to-VD2 T-cell ratio as an early marker for severe COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zini, G.; Bellesi, S.; Ramundo, F.; d’Onofrio, G. Morphological anomalies of circulating blood cells in COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 870–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiti, L.; Markovič, T.; Lainscak, M.; Farkaš Lainščak, J.; Pal, E.; Mlinarič-Raščan, I. The immunopathogenesis of a cytokine storm: The key mechanisms underlying severe COVID-19. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 82, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, S.M.; Geller, A.E.; Hu, X.; Tieri, D.; Ding, C.; Klaes, C.K.; Cooke, E.A.; Woeste, M.R.; Martin, Z.C.; Chen, O.; et al. A specific low-density neutrophil population correlates with hypercoagulation and disease severity in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e148435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y. Advances in the mechanism of bacterial escape neutrophil killing. Chin. J. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 38, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Sheng, J.; Carlson, J.; Wang, S. Aging-induced fragility of the immune system. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 509, 110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Dupuis, G.; Le Page, A.; Frost, E.H.; Cohen, A.A.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunosenescence and inflammaging as two sides of the same coin: Friends or foes? Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Page, A.L.; Fortin, C.; Witkowski, J.M.; Dupuis, G.; Larbi, A. Cellular signaling in the aging immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 29, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapri-Pardes, E.; Hanoch, T.; Maik-Rachline, G.; Murbach, M.; Bounds, P.L.; Kuster, N.; Seger, R. Activation of Signaling Cascades by Weak Extremely Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1533–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahaki, H.; Tanzadehpanah, H.; Jabarivasal, N.; Sardanian, K.; Zamani, A. A review on the effects of extremely low frequency electromagnetic foeld (ELF-EMF) in cytokines of innate and adaptive immunity. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2019, 38, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniedzialek, B.; Rzymski, P.; Nawrocka-Bogusz, H.; Jaroszyk, F.; Wiktorowicz, K. The effect of electromagnetic field on reactive oxygen species production in human neutrophils in vitro. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2013, 32, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNIRP. Guidelines for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (100 kHz–300 GHz). Health Phys. 2020, 118, 483–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbach, L.A.; Philippi, J.G.M.; Cuppen, J.J.M.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; Verburg-van Kemenade, B.M.L. Calcium signalling in human neutrophil cell lines is not affected by low-frequency electromagnetic fields. Bioelectromagnetics 2015, 36, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osera, C.; Amadio, M.; Falone, S.; Fassina, L.; Magenes, G.; Amicarelli, F.; Ricevuti, G.; Govoni, S.; Pascale, A. Pre-exposure of neuroblastoma cell line to pulsed electromagnetic field prevents H2O2-induced ROS production by increasing MnSOD activity. Bioelectromagnetics 2015, 36, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, H.G.; Worster, S.; Kattnig, D.R.; Steers, C.; Jin, Y.; Manolopoulos, D.E.; Mouritsen, H.; Hore, P.J. The quantum needle of the avian magnetic compass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4634–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, M.M.; Simkó, M.; Mattsson, M.-O.; Pioli, C. Immune-Modulating Perspectives for Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields in Innate Immunity. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.W.; Graham, K.; Prato, F.S.; McKay, J.; Forster, P.M.; Moulin, D.E.; Chari, S. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial Using a Low-Frequency Magnetic Field in the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Chronic Pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2007, 12, 626072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, D.; Zhai, M.; Tong, S.; Xu, F.; Cai, J.; Shen, G.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, K.; Liu, J.; et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields promote osteogenesis and osseointegration of porous titanium implants in bone defect repair through a Wnt/β-catenin signaling-associated mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Mustapova, Z.; Kulsharova, G.; Bulanin, D.; Mikhalovsky, S. Therapeutic potential of electromagnetic fields for tissue engineering and wound healing. Cell Prolif. 2014, 47, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.L.; Ang, D.C.; Almeida-Porada, G. Targeting Mesenchymal Stromal Cells/Pericytes (MSCs) With Pulsed Electromagnetic Field (PEMF) Has the Potential to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmusharaf, M.A.; Cuppen, J.J.; Grooten, H.N.; Beynen, A.C. Antagonistic effect of electromagnetic field exposure on coccidiosis infection in broiler chickens. Poultry Sci. 2007, 86, 2139–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, J.J.M.; Wiegertjes, G.F.; Lobee, H.W.J.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; Elmusharaf, M.A.; Beynen, A.C.; Grooten, H.N.A.; Smink, W. Immune stimulation in fish and chicken through weak low frequency electromagnetic fields. Environmentalist 2007, 27, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenspire, A.J.; Kindzelskii, A.L.; Simon, B.J.; Petty, H.R. Real-time control of neutrophil metabolism by very weak ultra-low frequency pulsed magnetic fields. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 3334–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, C.; Sahin, F.; Chen, Y.; Falldorf, K.; Ronniger, M.; Histing, T.; Nussler, A.K.; Ehnert, S. NET Formation Was Reduced via Exposure to Extremely Low-Frequency Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, I.I.; Mikhalchik, E.V.; Gusev, A.A.; Balabushevich, N.G.; Gusev, S.A.; Kazarinov, K.D. Extremely high-frequency electromagnetic radiation enhances neutrophil response to particulate agonists. Bioelectromagnetics 2018, 39, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kleijn, S.; Ferwerda, G.; Wiese, M.; Trentelman, J.; Cuppen, J.; Kozicz, T.; de Jager, L.; Hermans, P.W.; Verburg-van Kemenade, B.M. A short-term extremely low frequency electromagnetic field exposure increases circulating leukocyte numbers and affects HPA-axis signaling in mice. Bioelectromagnetics 2016, 37, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Pan, Y.; Wu, R.; Lv, Y. Innate Immune Regulation Under Magnetic Fields With Possible Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 582772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.W. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 23, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, M.; Okuya, K.; Tokorozaki, K.; Haraguchi, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Ozawa, M. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Outbreak in Endangered Cranes, Izumi Plain, Japan, 2022–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassatella, M.A.; Östberg, N.K.; Tamassia, N.; Soehnlein, O. Biological Roles of Neutrophil-Derived Granule Proteins and Cytokines. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, S.; Ghimire, L.; Jin, L.; Jeansonne, D.; Jeyaseelan, S. Regulation of emergency granulopoiesis during infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 961601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergadi, E.; Kolliniati, O.; Lapi, I.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Alexaki, V.I.; Diamantaki, E.; Vaporidi, K.; Hatzidaki, E.; Papadaki, H.A.; et al. An IL-10/DEL-1 axis supports granulopoiesis and survival from sepsis in early life. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drifte, G.; Dunn-Siegrist, I.; Tissières, P.; Pugin, J. Innate immune functions of immature neutrophils in patients with sepsis and severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, W.; Tian, L.; Brown, B.R.; Walters, M.S.; Metcalf, J.P. IRF7 Is Required for the Second Phase Interferon Induction during Influenza Virus Infection in Human Lung Epithelia. Viruses 2020, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorn, K.L. Innate Immunity and Influenza A Virus Pathogenesis: Lessons for COVID-19. Microbiol. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 563850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purbey, P.K.; Roy, K.; Gupta, S.; Manash, K.; Paul, M.K. Mechanistic insight into the protective and pathogenic immune-responses against SARS-CoV-2. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 156, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Neutrophil | Neutrophillic Granulocyte | Short-lived, free-ranging, and self-propagated phagocytic white blood cells with important functions in the innate immune system. Characterized by their granules containing cytokines and antimicrobial compounds that are excreted when activated. They phagocytose (eat) bacteria- and virus-infected cells and produce NETs, involved in the early phase of inflammation. |

| NET, NETosis | Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (formation) | NET formation allows neutrophils to kill extracellular pathogens while minimizing damage to host cells by releasing sticky clouds of DNA material and granule-derived enzymes that catch and kill microbes. |

| PAMPs and DAMPs | Pathogen- and Disease-Associated Molecular Patterns | Cells of the immune system employ PRRs and TLRs to recognize pathogens and damaged host cells and related proteins. PAMPs are derived from microorganisms while DAMPs are originally intracellular proteins or nucleic acids released upon cell death. |

| PRRs & TLRs | Pattern Recognition Receptors and Toll-Like Receptors | Immune cells express receptor proteins in and on the cell membrane that recognize PAMPs & DAMPs and thereby modify cell function such as activation and cytokine production and/or excretion. Different TLRs recognize different (types) of non-self material and provide rapid innate immune responses. |

| RIG-I, MDA5, NOD1/2, NLRP3, CD8+, RIG-I, MDA5, NOD1/2, NLRP3, Fc/Fcγ receptors, CR1/3, Dectin-1/2 | PRRs in and on immune cells that aid in recognizing viral components that initiate the ensuing immune response, while bacterial PAMPs and cellular DAMPs trigger inflammation, and cytokine release (like IL-1β, IL-18) by activating NF-κB/MAPK signaling transduction pathways. | |

| Cytokine | Cytokines are signal proteins with immune regulatory functions and are released by cells and act by binding to specific receptors. | |

| IFN | Interferon | Interferons are a family of cytokines with different types and subclasses important against viral replication and for coordinating immune responses. |

| CXCxx | C-X-C Motif Chemokine | Chemokines are cytokines with specific functions determining cell trafficking, including neutrophil release from the bone marrow. |

| Cellular signaling pathways named after/producing NF-κB, MAPK, JAK-STAT, NADPH, MyD88 | A process by which chemical or physical signals at the cell surface are transmitted through a cell to the DNA by a complex network of molecular interactions. This result changes in the transcription or translation of genes, and post-translational and conformational changes in proteins that will be secreted affecting their function. | |

| IRF3, IRF7, NF-κB, AP-1, GATA-3, T-bet | Transcription factors are DNA-binding proteins that affect and regulate the transcription rate of genes that are driving the immune response. Different bacteria and viruses can eliminate some of these as an immune delay strategy, thus sabotaging the related pathway. | |

| IL8/10/12/18/1β, TNF | Interleukin, Tumor Necrosis Factor | Cytokines produced by the innate immune system that mostly cause inflammation while only few cytokines (like IL-10 and TRGF-b) are anti-inflammatory. The immune system maintains an equilibrium between pro- and anti-inflammatory signals to ensure a robust immune response without becoming self-destructive. |

| LF-EMFs | Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields | EMFs with frequencies below 300 kHz, radio wave frequency and below, containing insufficient energy to change chemical bonds causing, e.g., DNA damage. |

| ICNIRP | International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection | ICNIRP continuously reviews scientific publications on the effects of EMF exposure on health and advises the WHO (World Health Organization) and the EU (European Union) on setting safety standards. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cuppen, J.J.M.; Savelkoul, H.F.J. Immune Delay, Beyond Immune Evasion, as a Driver of Pathogen Propagation Competence Through Neutrophil Dysregulation, to be Mitigated by Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (LF-EMF). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010143

Cuppen JJM, Savelkoul HFJ. Immune Delay, Beyond Immune Evasion, as a Driver of Pathogen Propagation Competence Through Neutrophil Dysregulation, to be Mitigated by Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (LF-EMF). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuppen, Jan J. M., and Huub F. J. Savelkoul. 2026. "Immune Delay, Beyond Immune Evasion, as a Driver of Pathogen Propagation Competence Through Neutrophil Dysregulation, to be Mitigated by Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (LF-EMF)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010143

APA StyleCuppen, J. J. M., & Savelkoul, H. F. J. (2026). Immune Delay, Beyond Immune Evasion, as a Driver of Pathogen Propagation Competence Through Neutrophil Dysregulation, to be Mitigated by Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (LF-EMF). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010143