Inflammation as a Prognostic Marker in Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

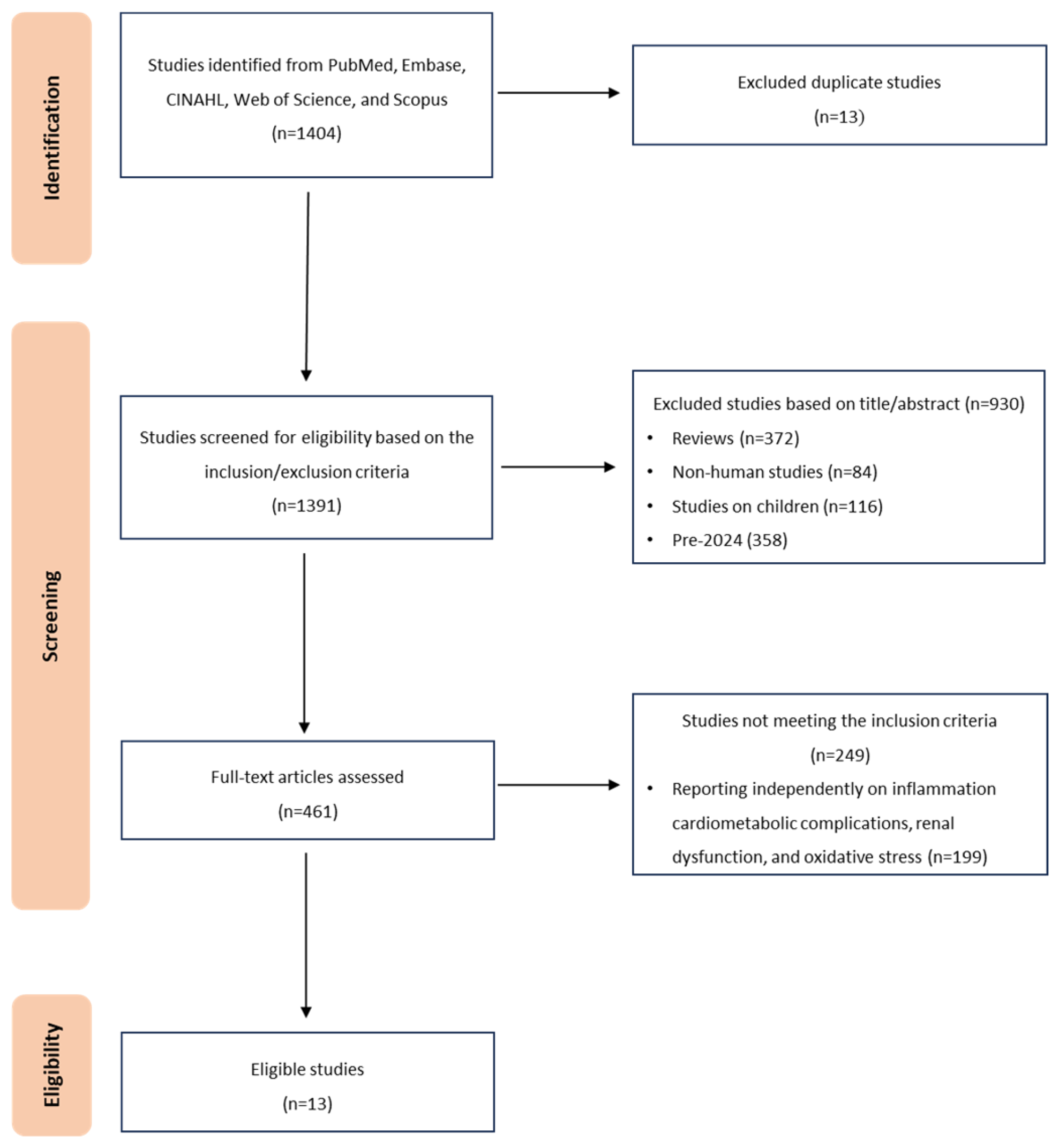

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Information Sources and Electronic Database Search Strategy

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Post-2024 CKMS Studies | Pre-2024 Studies (MetS, CKD + DM, cardio-renal-metabolic disorders) |

| Human adults (≥18 years) with CKMS | Pediatric populations (<18 years); animal or pre-clinical studies |

| Inflammation-related markers/indices (e.g., SIRI, SII, hs-CRP/HDL-C, DII, TyG indices) measured at baseline | Studies not reporting inflammatory markers/indices |

| Prognostic endpoints: all-cause or cardiovascular/renal mortality, CKMS progression, or composite adverse outcomes | Non-prognostic outcomes only (e.g., prevalence without outcomes) |

| Original, peer-reviewed research | Reviews, editorials, commentaries; protocols/abstracts without full data |

| Observational designs: prospective or retrospective cohorts; cross-sectional (hypothesis-generating only) | Randomized controlled trials without prognostic analyses; case reports/series without comparative data |

| No language restrictions; titles/abstracts screened via automated translation; full texts translated where feasible | Full-text translation to English not feasible or unreliable |

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. CKMS Stage Definitions

2.5. Quality Assessment

Certainty of Evidence and Measurement Outcome

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Quality of Evidence and Risk of Bias

Certainty of Evidence and Measurement Outcome

3.3. Cross-Sectional Studies

3.4. Cohort and Longitudinal Studies

3.5. Synthesis Without Meta-Analysis (SWiM)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Chow, S.L.; Mathew, R.O.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.-P. A synopsis of the evidence for the science and clinical management of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1636–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Shu, R.; Song, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, B.; Shi, H.; Gao, H. Association between different stages of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome and the risk of all-cause mortality. Atherosclerosis 2024, 397, 118585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, R.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Vaduganathan, M. Prevalence of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages in US adults, 2011–2020. JAMA 2024, 331, 1858–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimarco, V.; Izzo, R.; Pacella, D.; Manzi, M.V.; Trama, U.; Lembo, M.; Piccinocchi, R.; Gallo, P.; Esposito, G.; Morisco, C. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome during COVID-19: A propensity score-matched study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 218, 111926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuji, F.N.; Onyenekwe, C.C.; Ahaneku, J.E.; Ukibe, N.R. The effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the serum levels of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in HIV infected subjects. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites-Alves, C.; Luz, E.; Netto, E.M.; Ferreira, T.; Diaz, R.S.; Pedroso, C.; Page, K.; Brites, C. Immune activation, proinflammatory cytokines, and conventional risks for cardiovascular disease in HIV patients: A case-control study in Bahia, Brazil. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabhida, S.E.; McHiza, Z.J.; Mokgalaboni, K.; Hanser, S.; Choshi, J.; Mokoena, H.; Ziqubu, K.; Masilela, C.; Nkambule, B.B.; Ndwandwe, D.E.; et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein among people living with HIV on highly active antiretroviral therapy: A systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachofeiro, V.; Goicochea, M.; De Vinuesa, S.G.; Oubiña, P.; Lahera, V.; Luño, J. Oxidative stress and inflammation, a link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: New strategies to prevent cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedsadjadi, N.; Grant, R. The potential benefit of monitoring oxidative stress and inflammation in the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Antioxidants 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Shi, W.; Liu, B.; Wei, Y.; Investigators, N.-S.R. Prognostic implications of systemic immune-inflammation index in myocardial infarction patients with and without diabetes: Insights from the NOAFCAMI-SH registry. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Huang, J.; Xu, C.; Huang, T.; Wen, G.; Cheng, W. System inflammation response index: A novel inflammatory indicator to predict all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in the obese population. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nediani, C.; Giovannelli, L. Oxidative stress and inflammation as targets for novel preventive and therapeutic approches in non communicable diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Xia, Z.; Qing, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Gai, Z.; Hu, R.; Yuan, Y. Systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) is associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in population with chronic kidney disease: Evidence from NHANES (2001–2018). Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1338025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotemori, A.; Sawada, N.; Iwasaki, M.; Yamaji, T.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Ishihara, J.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Group, J.F.V.S. Validating the dietary inflammatory index using inflammatory biomarkers in a Japanese population: A cross-sectional study of the JPHC-FFQ validation study. Nutrition 2020, 69, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.D.; Moons, K.G.M.; Snell, K.I.E.; Ensor, J.; Hooft, L.; Altman, D.G.; Hayden, J.; Collins, G.S.; Debray, T.P.A. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ 2019, 364, k4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, S.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Z. Joint association of the inflammatory marker and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: A national prospective study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lian, W.; Wu, L.; Huang, A.; Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Qiu, Y.; Wei, Q. Joint association of estimated glucose disposal rate and systemic inflammation response index with mortality in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 0–3: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Z.; Bucci, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Gue, Y. Role of oxidative balance score in staging and mortality risk of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: Insights from traditional and machine learning approaches. Redox Biol. 2025, 81, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mo, D.; Zeng, W.; Dai, H. Association between triglyceride-glucose related indices and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among the population with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 0–3: A cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Lin, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Gao, Z.; Yan, Z.; Liu, C.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y. Association between dietary inflammatory index and cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome risk: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Gao, S.; Zhao, R.; Shen, P.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Duan, C.; Wang, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhou, L. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y. hs-CRP/HDL-C can predict the risk of all cause mortality in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 1–4 patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1552219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guan, Z.; Li, P. Association between dietary inflammatory index score and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study based on NHANES. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1557491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Xu, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, A.; Liu, Y.; Jin, M. Association of Three Composite Inflammatory and Lipid Metabolism Indicators with Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on NHANES 1999–2020. Mediat. Inflamm. 2025, 2025, 6691516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asija, N. Identification of inflammatory phenotypes of heart failure using systemic inflammation response index (SIRI): A cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 2021–2023. Res. Sq. 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, H.; Li, X. C-reactive protein-triglyceride glucose index in evaluating cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality incidence among individuals across stages 0–3 of cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Feng, W.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, X. Machine learning with decision curve analysis evaluates nutritional metabolic biomarkers for cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic risk: An NHANES analysis. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1597864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Chen, A.; Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; He, Q.; Xue, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zheng, Z. Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in patients with Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic syndrome: The mediating role of inflammatory biomarkers. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 386, 119429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Everett, B.M.; Lefkowitz, M.; Thuren, T.; Cornel, J.H. Inhibition of Interleukin-1β by Canakinumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2405–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait-Oufella, H.; Libby, P. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Prospects for Clinical Trials. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, A.; Hayden, J.A.; Stinson, J.; McGrath, P.J.; Chambers, C.T.; Tougas, M.E.; Wozney, L. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: Adapting the GRADE framework. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speer, T.; Dimmeler, S.; Schunk, S.J.; Fliser, D.; Ridker, P.M. Targeting innate immunity-driven inflammation in CKD and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Pounis, G.; De Curtis, A.; Costanzo, S.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. A score of low-grade inflammation and risk of mortality: Prospective findings from the Moli-sani study. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xing, Z.; Zhou, K.; Jiang, S. The predictive role of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in the prognosis of stroke patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Sun, Y.; Hua, Y. Monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio and systemic inflammation response index are associated with the risk of metabolic disorders and cardiovascular diseases in general rural population. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 944991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, T. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2337729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. In Fatty Acids and Lipotoxicity in Obesity and Diabetes; Novartis Foundation Symposia; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007; Volume 286, pp. 86–94; discussion 94–88, 162–163, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, N.; Godos, J.; Hébert, J.R.; Wirth, M.D.; Piuri, G.; Speciani, A.F.; Grosso, G. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Colorectal Cancer Risk-A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome | No of Studies | QUIPS Domains (Risk of Bias) | GRADE Domains | Reason for Downgrade | Final GRADE Decision | Overall Certainty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other | ||||||

| Mortality prediction (TyG, hs-CRP/HDL-C, SIRI, SII + OBS, CRP-TG) | 6 | Study confounding (low risk), study participants (low risk), prognostic factor measurement (low risk), statistical analysis (low risk), study attrition (moderate risk), outcome measurement (Low risk) | Non-randomized studies | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | None | Mortality associations were drawn mainly from US and Chinese cohorts. | Down-graded 1 level for indirect-ness | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Comorbidity prediction (SIRI | 1 | Study confounding (low risk), statistical analysis (low risk), study participants (low risk), prognostic factor measurement (low risk), study attrition (moderate risk), outcome measurement (low risk) | Non-randomized studies | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | None | Single study; limited generalizability | Downgraded 1 level for indirectness | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| CKMS risk/prevalence (E-DII, SII, NHR/LHR/MHR, RAR, NPAR, SIRI, HOMA-IR) | 5 | Study confounding (low risk), study attrition (high risk), prognostic factor measurement (low risk), outcome measurement (low risk) | Non-randomized studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Plausible residual confounding | Residual con-founding likely | Downgraded 1 level for other considerations | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Mental Health–Inflammation pathway (PHQ-9 mediated by SIRI) | 1 | Confounding (low risk), statistical analysis (low risk), study confounding (low risk), study participants (low risk), prognostic factor measurement (low risk), statistical analysis (Low risk), outcome measurement (low risk) | Non-randomized studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | None | Evidence from one non-randomized cohort | Downgraded 1 level for indirectness | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Ref. | Study Design & Setting | Population (N, Mean Age, Gender) | Inflammatory Indices | Prognostic Implications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al., 2025 [21] | Prospective, USA (NHANES) | 6383 participants; mean age 49.9 years; 50.5% male | TyG-derived indices | Associated with higher all-cause mortality | Elevated TyG-derived indices were predictive of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in participants with CKMS stages one and three. |

| Han et al., 2025 [24] | Prospective, China | 6719 participants; mean age 59.0 years; 47% male | hs-CRP/HDL-C | Association observed with long-term all-cause/CVD mortality | A higher ratio was linearly associated with increased 10-year all-cause mortality, with the risk compounded by the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and older age. |

| Cao et al., 2025 [18] | Prospective, USA | 29,459 participants; mean age 49.8 years; 72% male | SIRI | Association with all-cause and CVD mortality reported | Individuals with a high SIRI who were in CKMS stages three or four experienced the greatest risk of mortality, especially if they were younger than 60 years. |

| Chen, Lian et al., 2025 [19] | Prospective, USA | 18,295 participants; mean age 45.2 years; 51.6% female | SIRI + Egdr | High-risk metabolic–inflammatory phenotype | Concurrent elevation of the SIRI and a reduced eGDR doubled the risk of mortality, with a stronger association in participants younger than 60 years. |

| Chen, Wu et al., 2025 [20] | Prospective, USA | 21,609 participants; mean age 52.0 years; 54% male | SII + Oxidative Balance Scores (OBS) | Inflammation + oxidative stress | The OBS partially mediated the association between SII and mortality; in exploratory analyses, adding OBS to a LightGBM model yielded numerically higher internal performance metrics but was not externally validated, so no claims of improved predictive performance are made. |

| Li et al., 2025 [28] | Prospective, CHARLS (China) | 17,705 mid-to-late-adulthood participants | CRP-TG Index (CTI) | CVD incidence & mortality | Each unit increase in the CRP-TG index was associated with a 97% higher risk of death; the relationship between the index and cardiovascular disease was non-linear, whereas the association with all-cause mortality was linear. |

| Huang et al., 2025 [29] | Retrospective, USA (NHANES) | 19,884 adults | RAR, NPAR, SIRI, HOMA-IR | CKMS prediction & mortality | Among the evaluated indices, the red blood cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio was the most associated with CKMS, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.907; the relationships between the indices and mortality displayed non-linear patterns. |

| Wang et al., 2025 [30] | Prospective, USA (NHANES) | 12,314 adults | PHQ-9 score, SIRI mediation | Mental health–inflammation pathway | Higher scores on PHQ-9, reflecting depressive symptoms, were associated with increased mortality among individuals in CKMS stages one to three; the SIRI mediated approximately 12% of this relationship. |

| Prognostic Factor | No. of Studies | Direction of Effect | Effect Size Range (HR) | Heterogeneity Summary | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRI | 2 | ↑ Risk | 1.16–1.84 | I2 = 98.3%, τ2 =0.1046, p < 0.0001 | Low risk |

| SII | 1 | ↑ Risk | 1.18 | Single study | Low risk |

| TyG-WC | 1 | ↑ Risk | 1.5 | Single study | Low risk |

| hs-CRP/HDL-C | 1 | ↑ Risk | 1.15 | Single study | Low risk |

| CRP–TG Index (CTI) | 1 | ↑ Risk | 1.95 | Single study | Low risk |

| PHQ-9 score, SIRI mediation | 1 | ↑ Risk | 1.07 | Single study | Low risk |

| RAR, NPAR, SIRI, HOMA-IR | 1 | ↑ Risk | 2.38 | Single study | Moderate risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mabhida, S.E.; Mokoena, H.; Sello, M.G.; George, C.; Ndlovu, M.; Mabi, T.; Martins, S.; Ndlovu, I.S.; Azu, O.; Kengne, A.P.; et al. Inflammation as a Prognostic Marker in Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010134

Mabhida SE, Mokoena H, Sello MG, George C, Ndlovu M, Mabi T, Martins S, Ndlovu IS, Azu O, Kengne AP, et al. Inflammation as a Prognostic Marker in Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010134

Chicago/Turabian StyleMabhida, Sihle E., Haskly Mokoena, Mamakase G. Sello, Cindy George, Musawenkosi Ndlovu, Thabsile Mabi, Sisa Martins, Innocent S. Ndlovu, Onyemaechi Azu, André P. Kengne, and et al. 2026. "Inflammation as a Prognostic Marker in Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010134

APA StyleMabhida, S. E., Mokoena, H., Sello, M. G., George, C., Ndlovu, M., Mabi, T., Martins, S., Ndlovu, I. S., Azu, O., Kengne, A. P., & Mchiza, Z. J. (2026). Inflammation as a Prognostic Marker in Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010134