TAS1R3 Regulates GTPase Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells for Glucose Uptake

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

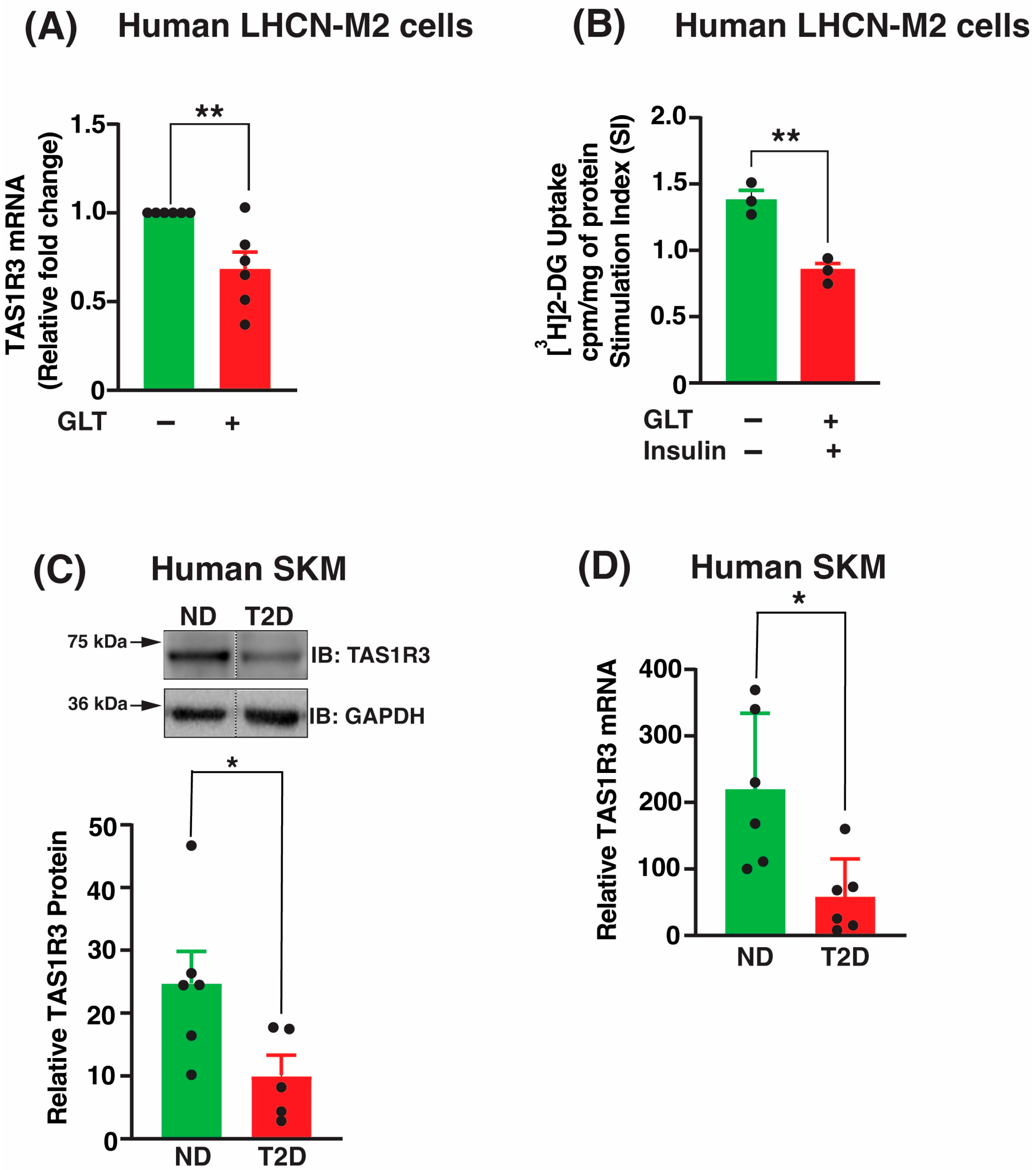

2.1. TAS1R3 Transcript and Protein Levels Are Decreased in T2D Human Skeletal Muscle

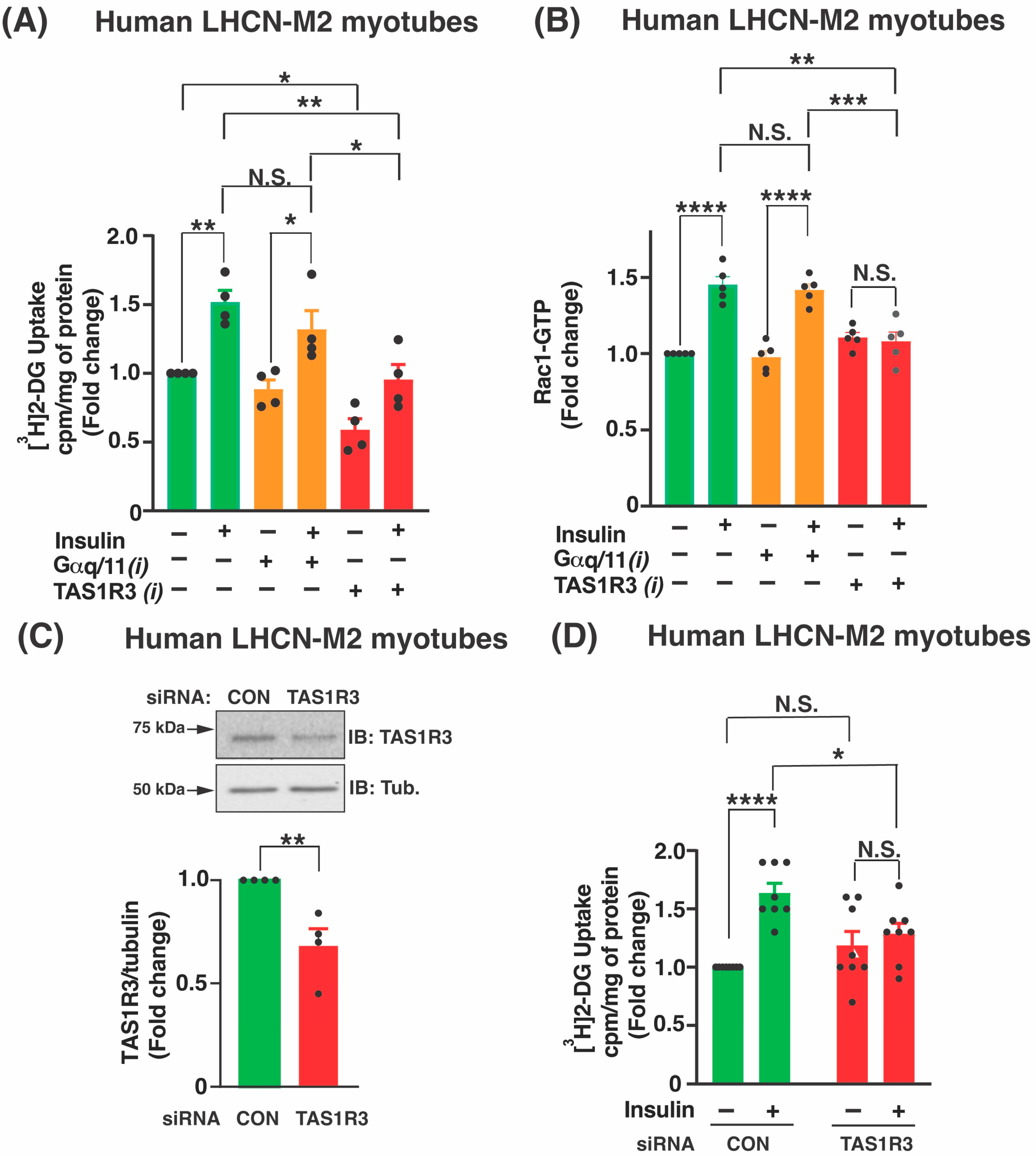

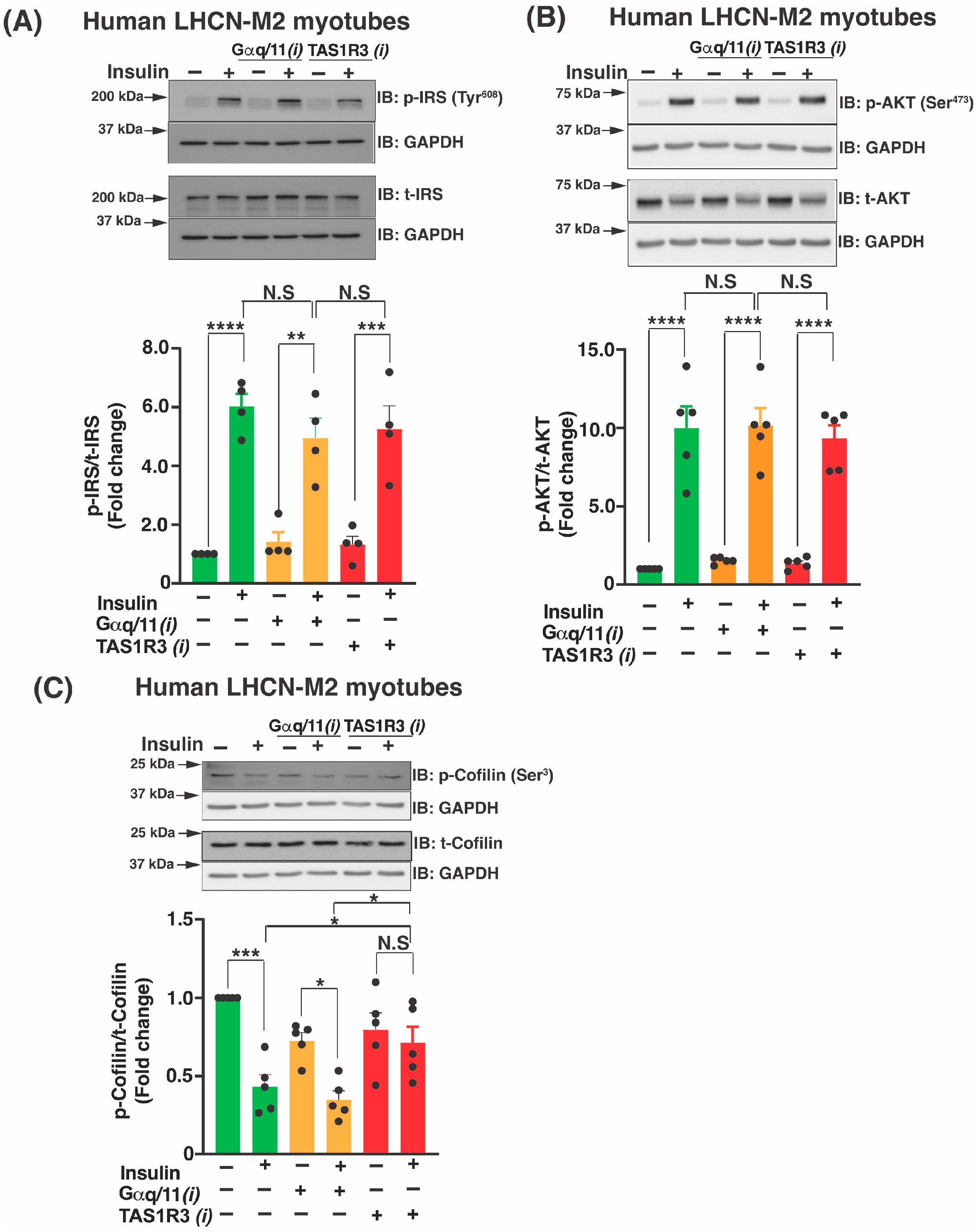

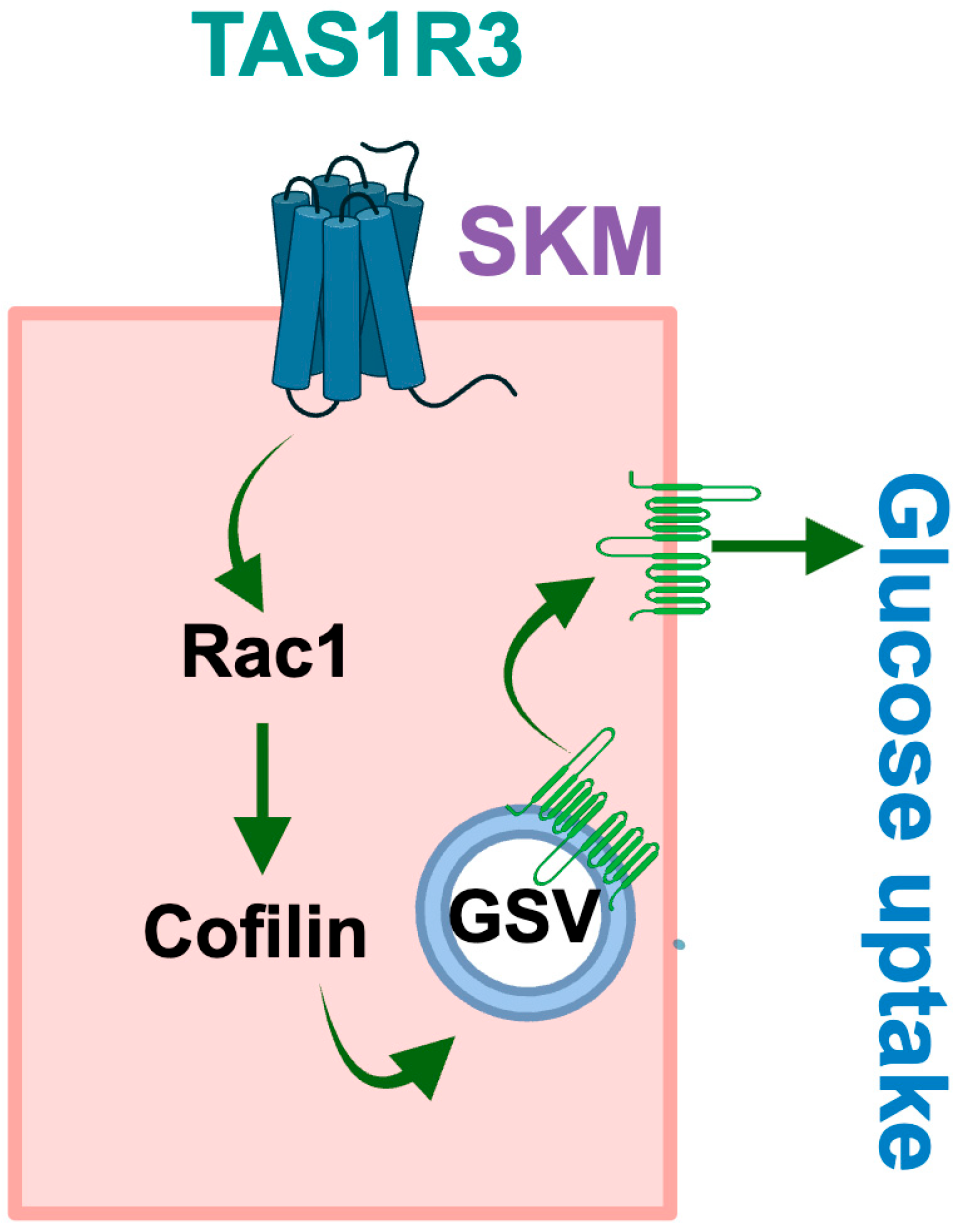

2.2. TAS1R3 Inhibition Impedes Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Uptake via a Non-Canonical Insulin Signaling Pathway

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. LHCN-M2 Myoblast Cell Culture

4.2. Human Skeletal Muscle

4.3. Quantitative PCR

4.4. Immunoblot Analysis

4.5. LHCN-M2 2-Deoxyglucose Uptake

4.6. Small Interfering RNA Transfection

4.7. G-LISA for Rac1 Activation Assay

4.8. Insulin Signaling Analysis

4.9. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Rooney, M.R.; Fang, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Ozkan, B.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J.; Selvin, E. Global Prevalence of Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.F.; Dufour, S.; Savage, D.B.; Bilz, S.; Solomon, G.; Yonemitsu, S.; Cline, G.W.; Befroy, D.; Zemany, L.; Kahn, B.B.; et al. The role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12587–12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandforth, L.; Kullmann, S.; Sandforth, A.; Fritsche, A.; Jumpertz-von Schwartzenberg, R.; Stefan, N.; Birkenfeld, A.L. Prediabetes remission to reduce the global burden of type 2 diabetes. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 36, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Farrokhi, F.R.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Insulin resistance: Review of the underlying molecular mechanisms. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 8152–8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Tripathy, D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, S157–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, E.; Simonson, D.C.; Katz, L.D.; Reichard, G., Jr.; Bevilacqua, S.; Barrett, E.J.; Olsson, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. The disposal of an oral glucose load in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Metabolism 1988, 37, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaud, D.; Jacot, E.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Maeder, E.; Jequier, E.; Felber, J.P. The effect of graded doses of insulin on total glucose uptake, glucose oxidation, and glucose storage in man. Diabetes 1982, 31, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Shu, D.; Meng, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Xiao, X.; Guo, W.; Chen, F. Higher Risk of Sarcopenia in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: NHANES 1999–2018. Obes. Facts 2023, 16, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; de Rekeneire, N.; Harris, T.B.; Schwartz, A.V.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Newman, A.B. Decreased muscle strength and quality in older adults with type 2 diabetes: The health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.C.; Weeldreyer, N.R.; Leicht, Z.S.; Angadi, S.S.; Liu, Z. Exercise Intolerance in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e035721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ballantyne, C.M. Skeletal muscle inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espino-Gonzalez, E.; Dalbram, E.; Mounier, R.; Gondin, J.; Farup, J.; Jessen, N.; Treebak, J.T. Impaired skeletal muscle regeneration in diabetes: From cellular and molecular mechanisms to novel treatments. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1204–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Zhi, L.; Liu, H. Semaglutide Therapy and Accelerated Sarcopenia in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A 24-Month Retrospective Cohort Study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 5645–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linge, J.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Neeland, I.J. Muscle Mass and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: Adaptive or Maladaptive Response to Weight Loss? Circulation 2024, 150, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.; Phillips, S.M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Heymsfield, S.B. Muscle matters: The effects of medically induced weight loss on skeletal muscle. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Neeland, I.J.; Dahlqvist Leinhard, O.; Fernandez Lando, L.; Bray, R.; Linge, J.; Rodriguez, A. Tirzepatide and muscle composition changes in people with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3 MRI): A post-hoc analysis of a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulli, G.; Ferrannini, E.; Stern, M.; Haffner, S.; DeFronzo, R.A. The metabolic profile of NIDDM is fully established in glucose-tolerant offspring of two Mexican-American NIDDM parents. Diabetes 1992, 41, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, A.E.; Kugler, B.A.; McDonald, P.M.; Veraksa, A.; Houmard, J.A.; Zou, K. Altered mitochondrial network morphology and regulatory proteins in mitochondrial quality control in myotubes from severely obese humans with or without type 2 diabetes. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanthan, P.; Hevener, A.L.; Karlamangla, A.S. Sarcopenia exacerbates obesity-associated insulin resistance and dysglycemia: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluthakal, R.; Esparza, D.; Hoolachan, J.M.; Balakrishnan, R.; Ahn, M.; Oh, E.; Jayasena, C.S.; Thurmond, D.C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Inter-Organ Miscommunications in T2D Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessin, J.E.; Saltiel, A.R. Signaling pathways in insulin action: Molecular targets of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roith, D.; Zick, Y. Recent advances in our understanding of insulin action and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylow, L.; Jensen, T.E.; Kleinert, M.; Hojlund, K.; Kiens, B.; Wojtaszewski, J.; Prats, C.; Schjerling, P.; Richter, E.A. Rac1 signaling is required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and is dysregulated in insulin-resistant murine and human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.T.; Sun, Y.; Koshkina, A.; Klip, A. Rac-1 superactivation triggers insulin-independent glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation that bypasses signaling defects exerted by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)- and ceramide-induced insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 17520–17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Baptiste, G.; Yang, Z.; Khoury, C.; Gaudio, S.; Greenwood, M.T. Peptide and non-peptide G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) in skeletal muscle. Peptides 2005, 26, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluthakal, R.; Ahn, M.; Oh, E.; Thurmond, D.C. TAS1R3 influences GTPase-dependent signaling in human islet β-cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1695980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.L.; Sutherland, K.; Pezos, N.; Brierley, S.M.; Horowitz, M.; Rayner, C.K.; A Blackshaw, L. Expression of taste molecules in the upper gastrointestinal tract in humans with and without type 2 diabetes. Gut 2009, 58, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, A.; Matsubara, T.; Kodama, N.; Kakuta, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Yoshida, R.; Kaminuma, O.; Hosomi, S.; Shinkawa, H.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Taste receptor type 1 member 3 in osteoclasts regulates osteoclastogenesis via detection of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, A.; Kim, S.K.; Chou, K.C.; Guthrie, B.; Goddard, W.A., III. Predicted Structure of Fully Activated Tas1R3/1R3′ Homodimer Bound to G Protein and Natural Sugars: Structural Insights into G Protein Activation by a Class C Sweet Taste Homodimer with Natural Sugars. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16824–16838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belloir, C.; Jeannin, M.; Karolkowski, A.; Briand, L. TAS1R2/TAS1R3 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Affect Sweet Taste Receptor Activation by Sweeteners: The SWEET Project. Nutrients 2025, 17, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauson, E.M.; Zaganjor, E.; Cobb, M.H. Amino acid regulation of autophagy through the GPCR TAS1R1-TAS1R3. Autophagy 2013, 9, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murovets, V.O.; Bachmanov, A.A.; Zolotarev, V.A. Impaired Glucose Metabolism in Mice Lacking the Tas1r3 Taste Receptor Gene. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmayer, P.; Kuper, M.; Kramer, M.; Konigsrainer, A.; Breer, H. Altered expression of gustatory-signaling elements in gastric tissue of morbidly obese patients. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, J.L.; Oh, E.; Thurmond, D.C. Exocytosis mechanisms underlying insulin release and glucose uptake: Conserved roles for Munc18c and syntaxin 4. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, R517–R531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C. Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance and Glucose Uptake. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Tunduguru, R.; Ahn, M.; Salunkhe, V.A.; Veluthakal, R.; Hwang, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; McCown, E.M.; Garcia, P.A.; Zhou, C.; et al. Changes in Skeletal Muscle PAK1 Levels Regulate Tissue Crosstalk to Impact Whole Body Glucose Homeostasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 821849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, L.; Oh, E.; Thurmond, D.C. Doc2b enrichment enhances glucose homeostasis in mice via potentiation of insulin secretion and peripheral insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, D.C.; Ahn, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Aslamy, A.; Thurmond, D.C. DOC2b enrichment mitigates proinflammatory cytokine-induced CXCL10 expression by attenuating IKKbeta and STAT-1 signaling in human islets. Metabolism 2025, 164, 156132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Balakrishnan, R.; Oh, E.; Veluthakal, R.; Thurmond, D.C. A Novel Role for DOC2B in Ameliorating Palmitate-Induced Glucose Uptake Dysfunction in Skeletal Muscle Cells via a Mechanism Involving beta-AR Agonism and Cofilin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Perdomo, G.; Brown, N.F.; O’Doherty, R.M. Fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in L6 myotubes is prevented by inhibition of activation and nuclear localization of nuclear factor kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41294–41301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanon, S.; Durand, C.; Vieille-Marchiset, A.; Robert, M.; Dibner, C.; Simon, C.; Lefai, E. Glucose Uptake Measurement and Response to Insulin Stimulation in In Vitro Cultured Human Primary Myotubes. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 55743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, D.B.J.; Meister, J.; Knudsen, J.R.; Dattaroy, D.; Cohen, A.; Lee, R.; Lu, H.; Metzger, D.; Jensen, T.E.; Wess, J. Skeletal Muscle-Specific Activation of G(q) Signaling Maintains Glucose Homeostasis. Diabetes 2019, 68, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, Y.; Yasuda, R.; Kuroda, M.; Eto, Y. Kokumi substances, enhancers of basic tastes, induce responses in calcium-sensing receptor expressing taste cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylow, L.; Nielsen, I.L.; Kleinert, M.; Moller, L.L.; Ploug, T.; Schjerling, P.; Bilan, P.J.; Klip, A.; Jensen, T.E.; Richter, E.A. Rac1 governs exercise-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle through regulation of GLUT4 translocation in mice. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 4997–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylow, L.; Moller, L.L.V.; Kleinert, M.; D’Hulst, G.; De Groote, E.; Schjerling, P.; Steinberg, G.R.; Jensen, T.E.; Richter, E.A. Rac1 and AMPK Account for the Majority of Muscle Glucose Uptake Stimulated by Ex Vivo Contraction but Not In Vivo Exercise. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1548–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunduguru, R.; Chiu, T.T.; Ramalingam, L.; Elmendorf, J.S.; Klip, A.; Thurmond, D.C. Signaling of the p21-activated kinase (PAK1) coordinates insulin-stimulated actin remodeling and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunduguru, R.; Zhang, J.; Aslamy, A.; Salunkhe, V.A.; Brozinick, J.T.; Elmendorf, J.S.; Thurmond, D.C. The actin-related p41ARC subunit contributes to p21-activated kinase-1 (PAK1)-mediated glucose uptake into skeletal muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 19034–19043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Boyd, J.; Brown, I.S.; Mason, C.; Smith, K.R.; Karolyi, K.; Maurya, S.K.; Meshram, N.N.; Serna, V.; Link, G.M.; et al. The TAS1R2 G-protein-coupled receptor is an ambient glucose sensor in skeletal muscle that regulates NAD homeostasis and mitochondrial capacity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauson, E.M.; Zaganjor, E.; Lee, A.Y.; Guerra, M.L.; Ghosh, A.B.; Bookout, A.L.; Chambers, C.P.; Jivan, A.; McGlynn, K.; Hutchison, M.R.; et al. The G protein-coupled taste receptor T1R1/T1R3 regulates mTORC1 and autophagy. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, M.S.; Weinstein, N.; Newby, J.B.; Plattes, M.M.; Foster, H.E.; Arthur, J.W.; Ward, T.D.; Shively, S.R.; Shor, R.; Nathan, J.; et al. Loss of the nutrient sensor TAS1R3 leads to reduced bone resorption. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 74, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Oh, E.; Merz, K.E.; Aslamy, A.; Veluthakal, R.; Salunkhe, V.A.; Ahn, M.; Tunduguru, R.; Thurmond, D.C. DOC2B promotes insulin sensitivity in mice via a novel KLC1-dependent mechanism in skeletal muscle. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, K.E.; Hwang, J.; Zhou, C.; Veluthakal, R.; McCown, E.M.; Hamilton, A.; Oh, E.; Dai, W.; Fueger, P.T.; Jiang, L.; et al. Enrichment of the exocytosis protein STX4 in skeletal muscle remediates peripheral insulin resistance and alters mitochondrial dynamics via Drp1. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Garcia, P.A.; Veluthakal, R.; Huss, J.M.; Hoolachan, J.M.; Thurmond, D.C. Toward Ameliorating Insulin Resistance: Targeting a Novel PAK1 Signaling Pathway Required for Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluthakal, R.; Sidarala, V.; Kowluru, A. NSC23766, a Known Inhibitor of Tiam1-Rac1 Signaling Module, Prevents the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes in the NOD Mouse Model. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NDRI# | Age | Race | Gender | BMI | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND09743 | 46 | Caucasian | M | 34.9 | ND |

| ND09744 | 62 | Caucasian | M | 28.2 | ND |

| ND09749 | 49 | Caucasian | F | 21.6 | ND |

| ND09706 | 45 | Caucasian | M | 44.5 | T2D |

| ND09754 | 67 | Caucasian | M | 32.3 | T2D |

| ND10105 | 53 | Caucasian | F | 28 | T2D |

| ND13347 | 78 | Caucasian | M | 26.4 | ND |

| ND13230 | 68 | Caucasian | F | 40.2 | ND |

| ND13216 | 54 | Caucasian | M | 31.3 | ND |

| ND13214 | 74 | Caucasian | M | 32.1 | T2D |

| ND13363 | 59 | Caucasian | M | 41.5 | T2D |

| ND13239 | 58 | Caucasian | M | 50.3 | T2D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hoolachan, J.M.; Balakrishnan, R.; Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C.; Veluthakal, R. TAS1R3 Regulates GTPase Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells for Glucose Uptake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010103

Hoolachan JM, Balakrishnan R, Merz KE, Thurmond DC, Veluthakal R. TAS1R3 Regulates GTPase Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells for Glucose Uptake. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoolachan, Joseph M., Rekha Balakrishnan, Karla E. Merz, Debbie C. Thurmond, and Rajakrishnan Veluthakal. 2026. "TAS1R3 Regulates GTPase Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells for Glucose Uptake" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010103

APA StyleHoolachan, J. M., Balakrishnan, R., Merz, K. E., Thurmond, D. C., & Veluthakal, R. (2026). TAS1R3 Regulates GTPase Signaling in Human Skeletal Muscle Cells for Glucose Uptake. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010103