1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a complex, often chronic condition caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system. It originates from damage to nerves involved in the neural pathways that transmit sensory information from the body to the brain [

1,

2].

NP also leads to peripheral and central sensitization, resulting in an increased response to painful stimuli (hyperalgesia) and pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli (allodynia). These alterations make NP not only a daily and persistent struggle for patients who suffer from it but also a significant economic burden on healthcare systems [

1,

3]. Moreover, the current pharmacological treatments are often ineffective, requiring high doses for prolonged periods of time, which lead to numerous side effects [

4,

5].

One of the main mechanisms underlying NP caused by peripheral nerve injury is thought to be the generation of ectopic impulses in nociceptive primary sensory neurons (nociceptors), either at the site of the injury or in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [

1]. These abnormal impulses transmitted to the central nervous system are interpreted by the brain as pain signals, leading to NP. A wide variety of molecular mechanisms are involved in the development of NP, one of them is inflammation. The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, is the main intracellular sensor of inflammation. Upregulation of NLRP3 expression has been observed in the DRG of animals with NP, suggesting that peripheral activation of this inflammasome plays a key role in the contribution of inflammation to the pathogenesis of NP [

6,

7].

Oxidative stress also plays a crucial role in the development of NP. Damaged peripheral sensory neurons undergo mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to NP through several molecular mechanisms, such as facilitating the activation of macrophages in peripheral nerves that potentiate the inflammatory responses. In addition, they also cause direct neuronal damage, enhance central sensitization, and modulate nociceptive signaling, altogether contributing to the progress and maintenance of NP [

8]. As a consequence, increased levels of oxidative markers, such as 4-HNE, were detected in the DRG and some brain areas of sciatic nerve-injured mice [

7].

Both inflammation and oxidative stress contribute to synaptic plasticity changes in nociceptors and glial cells, leading to their central and peripheral sensitization, resulting in hyperalgesia and allodynia. In persistent pain conditions, there is an increase in the MAPK signaling pathways in glial cells, including the ERK 1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways. These changes promote neuroinflammation and, consequently, pain hypersensitivity. For example, following nerve injury, ERK 1/2 has been shown to be initially phosphorylated in microglia, suggesting its implication in the induction of chronic pain, and later in astrocytes, where it is thought to be involved in the maintenance of this state [

8,

9].

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway has been reported to participate in the onset of hypersensitivity to pain, particularly by contributing to the spinal cord sensitization, a crucial region modulating the transmission of nociceptive signals to the central nervous system [

10]. Experimental evidence demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of either PI3K or Akt attenuates NP behaviors, including mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, in animal models of peripheral nerve injury [

11]. Elevated levels of p-Akt have been observed in both the DRG and the spinal cord following nerve ligation, further supporting the contribution of this pathway to central and peripheral sensitization [

12].

First-line pharmacological management of NP comprised the use of gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) and antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [

1]. When these are insufficient or poorly tolerated, topical or systemic local anesthetics, e.g., lidocaine patches and high-concentration capsaicin patches, are prescribed. Finally, third-line treatments, including opioids or cannabinoids, may be considered, although these options are often limited by concerns about safety, tolerability, and long-term benefit [

13,

14].

Despite their prominent role as first-line treatments, gabapentinoids are not universally effective across all NP subtypes and are frequently associated with side effects such as dizziness, somnolence, and impaired attention or working memory, which can significantly impact patient adherence and daily functioning [

3,

14]. These limitations highlight the need to refine gabapentinoid-based approaches through optimized dosing strategies, personalized treatment selection, or combination therapies designed to enhance efficacy while minimizing adverse outcomes.

Cannabinoid receptor agonists have shown therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of NP. Preclinical investigations have demonstrated that selective activation of cannabinoid type-2 receptors (CB2R) elicits antinociceptive effects in multiple models of NP [

15,

16]. Nonetheless, their clinical effectiveness is limited, and their application is frequently associated with considerable adverse effects, including diminished attention and working memory [

3,

17]. Therefore, additional research into novel therapeutic strategies that incorporate combined treatments to augment analgesic efficacy while reducing side effects is essential.

Recent studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of molecular hydrogen (H

2) in the treatment of NP and other neurological disorders [

18]. Experimental evidence indicates that H

2 administration can markedly reduce mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, symptoms of NP [

19]. The analgesic and neuroprotective effects of H

2 are primarily attributed to its antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties, which collectively attenuate oxidative stress and neuroinflammatory signaling associated with chronic pain states [

20,

21]. H

2 can be efficiently administered via injection of hydrogen-rich water (HRW), facilitating accurate dosing and enhanced H

2 delivery while exhibiting minimal side effects or tolerance concerns [

22]. Therefore, HRW represents a promising medicinal approach, but further research to explore the synergistic effects of H

2 with conventional NP therapies is required.

The treatment of NP remains extremely challenging. Despite decades of research, 30–50% of patients are resistant to commonly used therapeutic strategies. The chronic nature of the condition and the high doses required for symptom control frequently result in undesirable side effects [

14]. That is why combined therapies that manage to reduce the high doses required by current treatments are receiving more interest. These approaches aim to enhance the analgesic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects, thereby improving patients’ quality of life and adherence to therapy.

In this study, we explore the combination of HRW with either JWH-133, a selective CB2R agonist, or pregabalin, a gabapentinoid, as new alternatives for the management of NP. Therefore using a mice model of NP induced by the chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve, we evaluated: (i) the dose-responses effects produced by the intraperitoneal administration of different doses of HRW, JWH-133 and pregabalin in the mechanical allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia provoked by CCI, (ii) the effectiveness of the combination of a low dose of HRW with either JWH-133 or pregabalin on inhibiting the nociceptive responses caused by CCI and (iii) the molecular pathways involved in the actions of these treatments, alone and combined, through assessing the expression of proteins related to oxidative stress, inflammation, plasticity changes and nociceptive signaling pathways by using Western blot analysis.

3. Discussion

NP is a highly prevalent and disabling condition that affects millions of people worldwide. However, the prolonged use of the most commonly prescribed treatments is often associated with several side effects, which can lead patients to discontinue medication. In this study, we investigate new combined treatments with HRW for the management of NP, aiming to reduce the high doses or the long-time administration of established treatments, such as pregabalin, or of tentative therapies, such as CB2R agonists.

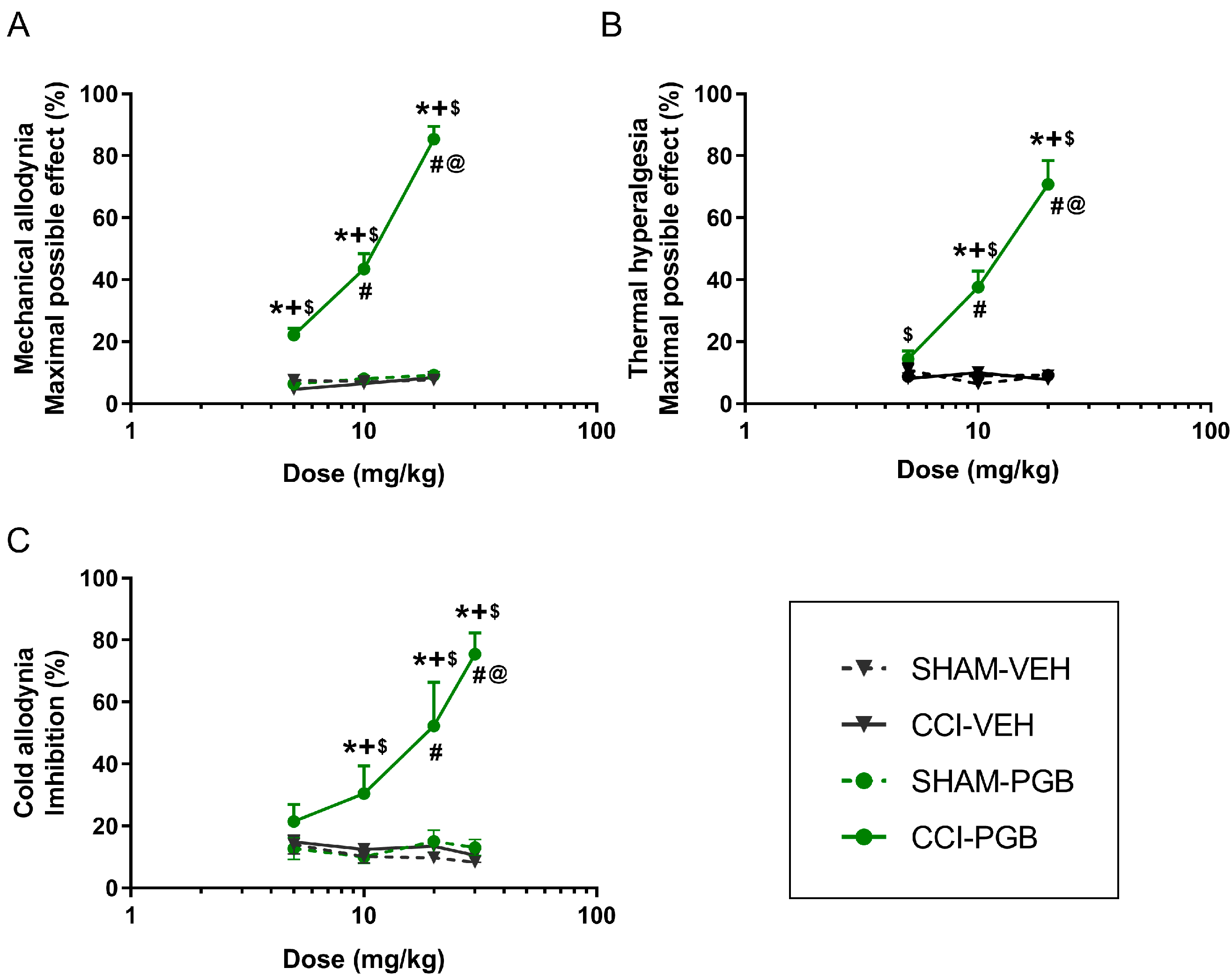

In a CCI mouse model, our results indicated that HRW significantly inhibited the mechanical allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia in a dose-dependent manner. This is particularly relevant as, to our knowledge, this is the first time that a dose–response curve for HRW has been established in a CCI-induced NP model. Regarding JWH-133, a CB2R agonist, or pregabalin, an anticonvulsant drug, both drugs also exhibited dose-dependent antinociceptive effects in CCI mice. These results are in line with previous studies reporting that CB2R agonists, such as JWH-015, dose-dependently reduced the hypersensitivity induced by peripheral nerve injury in rodents [

23]. Similarly, pregabalin had been reported to exert dose-dependent antiallodynic effects following its intraperitoneal administration in a mouse model of spared nerve injury, with similar ranges of doses tested by us (3–30 mg/kg) [

24]. Our findings further revealed the dose–response inhibitory effects induced by both drugs in other nociceptive responses, such as thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia provoked by CCI.

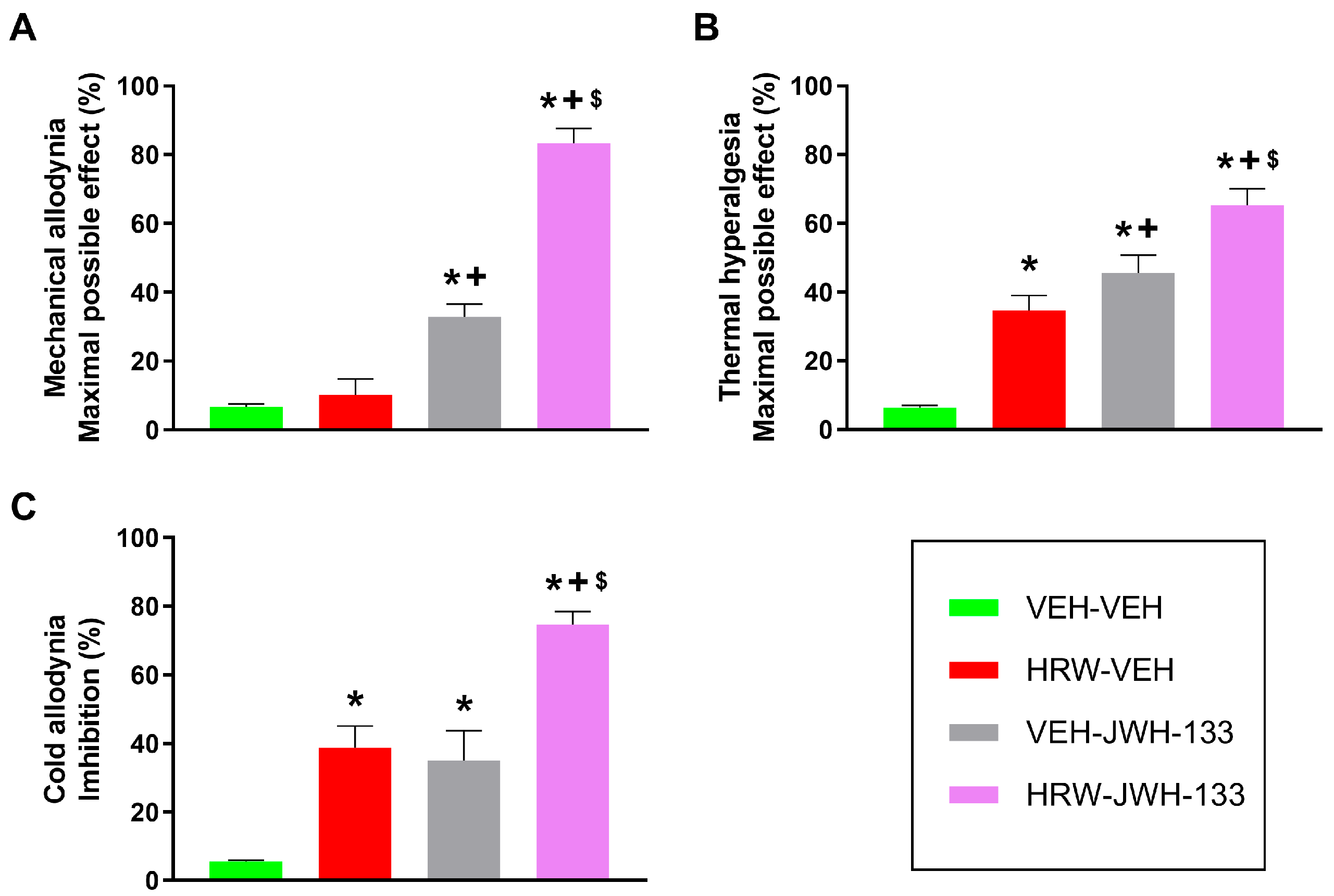

Our study further demonstrated that the co-administration of a low dose of HRW potentiated the analgesic effects produced by JWH-133 and pregabalin. That is, the combination of HRW and JWH-133 significantly enhanced the mechanical and thermal antiallodynic and thermal antihyperalgesic effects produced by each treatment given alone. This improvement is higher in the inhibition of allodynia than hyperalgesia. That is, the mechanical and thermal antiallodynic effects produced by HRW combined with JWH-133 are around 83% and 74%, respectively, in contrast to the 65% antihyperalgesic effects produced by this combined treatment. Suggesting that this combined treatment is more effective in improving the antiallodynic than the antihyperalgesic properties of JWH-133 under NP conditions. Other mixture treatments involving JWH-133 have also been assessed; for example, its co-administration with hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) donors also improved the pain reliever effects produced by this CB2R agonist in animals with NP [

25]. Furthermore, a synergistic interaction between JWH-015, another CB2R agonist, and morphine, a µ opioid receptor agonist, inhibiting NP induced by the spared nerve injury of the sciatic nerve has also been reported [

26]. Nevertheless, this study provides, for the first time, evidence of a positive interaction between H

2 and the CB2R system in the modulation of sciatic nerve injury–induced NP in mice. Given the favorable safety profile of H

2 compared with the well-known adverse effects of morphine, its co-administration with JWH-133 may represent a safer and more effective therapeutic strategy for the management of NP.

Our findings also demonstrated that a low dose of HRW can enhance the analgesic effectiveness of pregabalin, a first-line treatment for NP. The mechanical and thermal antiallodynic and antihyperalgesic actions produced by this drug combination were greater than those made by either treatment administered individually. Other combinations involving pregabalin have also been explored. For example, the co-administration of pregabalin with antidepressants, for instance tricyclics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, has been reported to effectively alleviate diabetic peripheral NP. Similarly, co-treatment of pregabalin with opioids has also shown analgesic efficacy, although addiction issues remain a concern [

27]. In preclinical models of NP, the co-administration of cobalt protoporphyrin IX (CoPP), an HO-1 inducer, and/or carbon monoxide-releasing molecule 2 (CORM-2) has been shown to potentiate the antiallodynic effects of pregabalin in spared nerve-injury induced NP in mice [

24]. Our results reported, for the first time, that pregabalin in combination with HRW results in a greater analgesic action, especially inhibiting mechanical allodynia, where the combined treatment achieved 93% inhibition versus those of 70% and 78% achieved in reducing thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia, respectively. The present findings highlight the combination of HRW with pregabalin as particularly advantageous compared with other pregabalin-based strategies previously reported. Although agents such as CoPP and CORM-2 have been reported to enhance pregabalin’s efficacy, their potential toxicity and limited translational applicability raise concerns regarding long-term safety. In contrast, HRW offers a well-tolerated source of H

2 with established antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and it has been shown to exert these effects without notable side effects [

22].

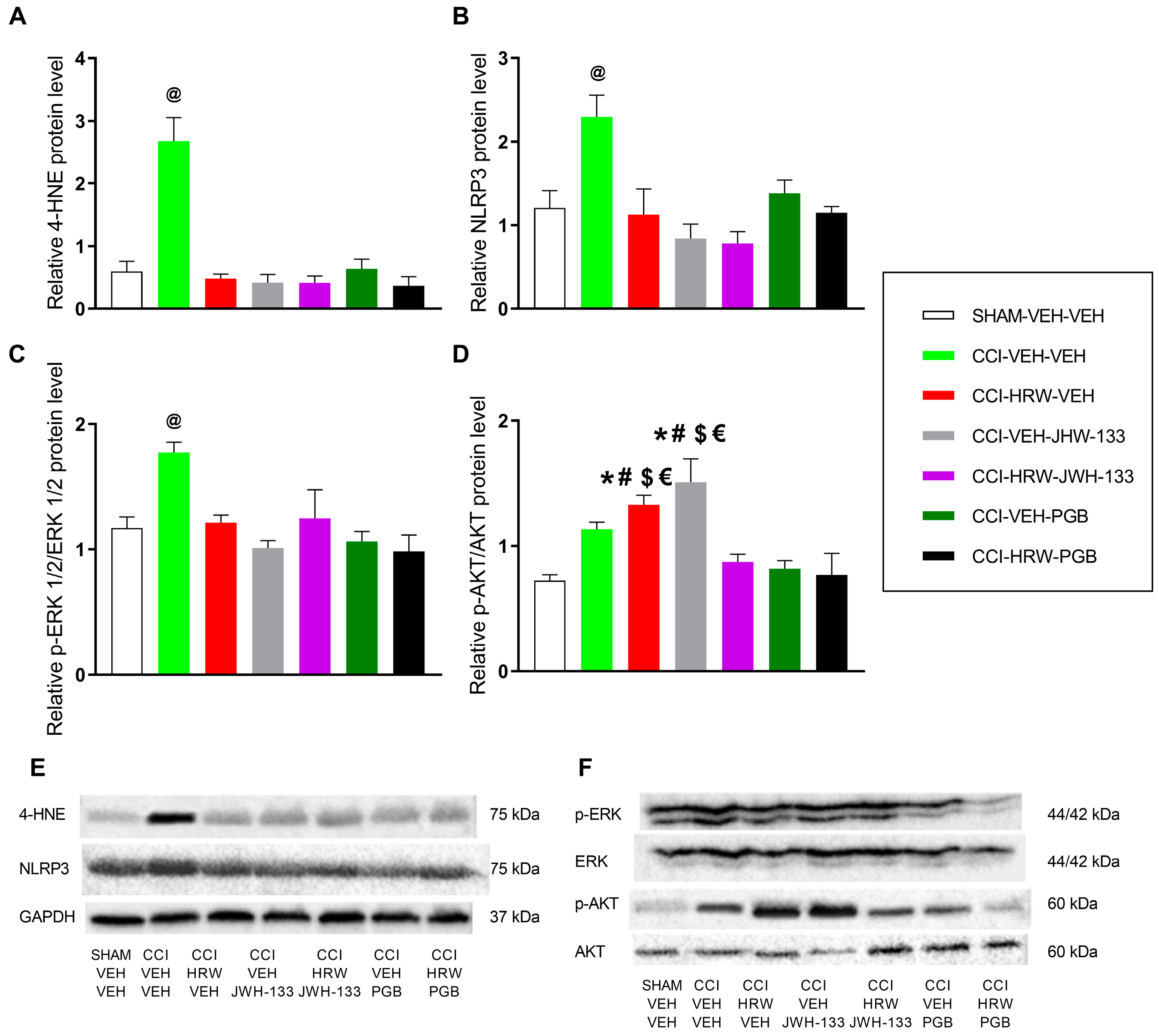

It is well established that oxidative stress is a critical contributor to the pathogenesis of NP. In the present study, we observed a marked increase in the expression of 4-HNE within the DRG of CCI mice. This alteration was normalized following treatment with HRW, JWH-133, or pregabalin administered individually. Evidence from previous studies supports the antioxidant properties of these agents when administered individually. Specifically, H

2 has been reported to exert part of its analgesic effects by neutralizing cytotoxic ROS [

19,

28] and by normalizing the overexpression of the oxidative stress marker 4-HNE while upregulating antioxidant enzymes such as SOD-1 in DRG of mice with NP [

29].

Similarly to H

2, activation of CB2R also attenuates oxidative stress by reducing ROS production, lipid peroxidation, and 4-HNE expression in the spinal cord of mice with oxaliplatin-induced NP [

30] and in in vitro models of osteoarthritis [

31]. Consistently, CB2R agonists have been shown to activate the Nrf2-mediated endogenous antioxidant pathway; for example, macrophages derived from mice with diet-induced obesity exhibit increased Nrf2 activity following CB2R stimulation [

32]. Pregabalin also exerts part of its palliative effects by modulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes, including HO-1 and Arg-1 [

24]. Our data further showed that the combined administration of HRW with either JWH-133 or pregabalin fully restored the elevated 4-HNE levels to baseline, suggesting that all treatments converge on a common redox-related mechanism. The simultaneous normalization of 4-HNE by all agents may reflect a broader and more efficient rebalancing of redox homeostasis, which may underlie the enhanced analgesic efficacy of the combined treatments. Nevertheless, other complementary mechanisms might be involved in the superior analgesic effects observed with the combined treatments, likely related to inflammation, plasticity changes, or nociceptive pathways activated during NP.

H

2 targets core pathways such as NLRP3 inflammasome and MAPK to regulate and suppress inflammation [

22]. Accordingly, the increased expression of NLRP3 induced by CCI in the DRG was inhibited by HRW. Since NLRP3 activation is promoted by oxidative stress, the reduction in ROS by HRW may also contribute to the attenuation of inflammatory responses [

28,

33]. In parallel, CB2R agonists have been shown to promote NLRP3 degradation through autophagy in spinal cord injury models [

6] and to exert peripheral anti-inflammatory effects by limiting immune cell migration and pro-inflammatory cytokine release at the injury site [

32,

34]. Similarly, pregabalin reduces NLRP3 expression, and its analgesic actions are associated with suppressed microglial activation and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α [

24]. Consistently, our results indicated that administration of JWH-133 or pregabalin, either alone or in combination with HRW, suppressed the overexpression of this inflammasome in the DRG of animals with NP. Therefore, the superior analgesic outcomes observed suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of HRW, JWH-133, and pregabalin given alone reinforced the analgesic properties of the combined therapies.

Hypersensitivity following nerve injury in different NP models correlates with increased phosphorylation of ERK, which is associated with synaptic plasticity in neurons, leading to abnormal signaling and increased excitability [

35]. Molecular analysis revealed that the expression of p-ERK increased in the DRG of animals with NP, thus contributing to the hypersensitivity manifested at 28 days after injury. Moreover, all individual treatments and combinations normalized the elevated p-ERK levels in the DRG of CCI mice. In agreement, HRW inhibits ERK 1/2 activation in the DRG of animals with chemotherapy-induced NP [

36], and the reduced expression of p-ERK 1/2 induced by CB2R activation contributed to the antinociceptive actions in a rat model of NP [

37]. In the same way, the antinociceptive mechanisms of pregabalin have also been associated with the inhibition of MAPK activation, such as reduced p-ERK 1/2 levels in spinal neurons, as demonstrated [

38,

39]. This study revealed that the co-administration of HRW with either JWH-133 or pregabalin also attenuated the nerve injury–induced up-regulation of p-ERK1/2 in the DRG of CCI mice, a signaling node critically involved in central and peripheral sensitization. This downregulation is consistent with the robust antihyperalgesic effects observed with both combined treatments. However, similar to what was observed for 4-HNE and NLRP3, no additional reduction in p-ERK1/2 expression was detected with the combined therapy compared with each compound administered individually. A likely explanation is that both HRW, JWH-133, and pregabalin fully normalized p-ERK1/2 levels to baseline when administered alone, thereby reaching a physiological floor beyond which further suppression is not achievable.

AKT phosphorylation, a regulator of nociceptive processing, plays an important role in the transmission of pain signals within the spinal cord and peripheral sensory pathways [

10,

40]. In our study, however, p-AKT regulation presented a complex pattern. Although CCI alone did not markedly elevate p-AKT, both HRW and JWH-133 administered as monotherapies increased its expression above SHAM levels. This response contrasts with the inhibitory effect of HRW on p-AKT reported in a paclitaxel-induced neuropathy model [

36], yet is consistent with evidence that CB2R activation can enhance AKT phosphorylation in immune cells [

34,

41]. Such discrepancies may reflect NP model-specific differences, and it is also possible that the relatively low dose of HRW used here was insufficient to counteract subtle CCI-induced changes in AKT signaling within the DRG. Notably, when HRW and JWH-133 were co-administered, p-AKT levels returned to baseline despite the increases produced by each agent alone. This normalization suggests that the combined treatment may rebalance upstream regulatory inputs such as oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, or CB2-related signaling that converge on the AKT pathway, thereby preventing compensatory activation and reducing AKT-dependent nociceptor sensitization. Although this theory should be interpreted cautiously, this coordinated suppression of AKT phosphorylation aligns with the superior analgesic effects observed with the combination therapy.

Our data further showed that pregabalin, whether administered alone or in combination with HRW, fully normalized p-AKT levels in the DRG of CCI mice. This reduction in AKT phosphorylation indicates an effective suppression of nerve-injury–induced neuronal sensitization and downstream nociceptive signaling, which contributes to the greater antinociceptive response observed with the combined treatment. Overall, these findings suggest that concomitant modulation of redox homeostasis, neuroinflammation, and the p-ERK1/2 and p-AKT signaling cascades induced by these combined therapies may recruit a broader, more integrated regulatory network that ultimately enhances its analgesic efficacy during NP.

The greater analgesic efficacy observed with the combination of HRW and JWH-133 or pregabalin highlights several promising avenues for clinical application. By simultaneously attenuating oxidative stress, inflammatory signaling, and maladaptive nociceptive pathways, HRW could enable effective pain control with lower doses of conventional analgesics, an approach that could significantly reduce the burden of adverse effects associated with chronic high-dose treatments in patients with NP.

However, some limitations of this study, such as the use only in male mice without addressing potential sex differences in pain mechanisms, oxidative stress, or drug responses, and the fact that it only evaluated the effects of acute intraperitoneal administration of these co-treatments without assessing the potential long-term adverse effects, oral bioavailability, and dosing equivalence, limit its translational and therapeutic relevance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Experimental Models

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the local Committee of Animal Use and Care of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (ethical code: 4581) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Commission’s directive (2010/63/EC) and the Spanish Law (RD 53/2013) regulating animal research.

Male C57BL/6 mice (5–6 weeks old) were obtained from Envigo Laboratories (Barcelona, Spain). Animals were group-housed under controlled conditions, at a 22 °C temperature and 66% humidity environment, exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle and unlimited access to water and food. Four male mice were kept in polypropylene cages outfitted with a carton hut and cellulose fragments to create an enriching atmosphere.

Behavioral testing was performed from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. following a one-week acclimatization period to the housing conditions. Animals were also acclimated to the testing room for 1 h before the commencement of the tests. For each test, the order of animals being tested was randomized daily, and each subject was tested at a different time on each test day. For each animal, two distinct investigators were involved: the primary investigator (SENF) administered the treatment in accordance with the randomization table. This researcher was uniquely cognizant of the treatment group allocation. An additional investigator (NAT), blinded to the treatment, evaluated the mechanical allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia, and cold allodynia of these subjects.

All efforts were made to minimize the animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used in accordance with the 3Rs principles (replacement, reduction, and refinement). The number of animals used in each group was 6 (n = 6). Animals were randomly assigned to each experimental group. Random numbers were generated using the standard = RAND ( ) function in Microsoft Excel. A total of 372 mice were used in this study.

4.2. Neuropathic Pain Model

To induce NP, a CCI of the sciatic nerve was performed in mice. Surgical procedures were carried out under isoflurane anesthesia (3% for induction and 2.5% for maintenance). After confirming the loss of the hind limb withdrawal reflex, the surgical site was shaved. Afterward, the biceps femoris and the gluteus superficialis were dissected, thereby exposing the sciatic nerve. Three ligatures were placed around the nerve using 4/0 silk sutures (Laboratorio Aragó, SL, Barcelona, Spain), spaced approximately 1 mm apart, ensuring the epineural circulation was not obstructed. SHAM-operated control mice underwent the same surgical procedure, excluding nerve ligation.

4.3. Nociceptive Tests

Mechanical allodynia was tested by evaluating the hind limb withdrawal reflex in response to von Frey filaments of increasing stiffness (0.4 to 3 g, North Coast Medical, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Mice were individually placed in transparent Plexiglas cylinders (20 cm height × 9 cm diameter) on an elevated wire mesh platform, allowing access to the plantar area of the hind paw.

The up-down method [

42] was used, starting with the 0.4 g filament. If a withdrawal response was observed, the filament with lower force was applied next; otherwise, a higher force filament was used. The threshold of the response was calculated using an Excel program (Microsoft Iberia, SRL, Barcelona, Spain) incorporating curve fitting of the data.

Thermal hyperalgesia was assessed using the plantar test (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy), which applies a radiant heat stimulus to the hind paw to measure paw withdrawal latency. Mice were individually placed in transparent Plexiglas cylinders (20 cm height × 9 cm diameter) on a glass platform. A heat source was applied under the plantar surface of the hind paw until a withdrawal response was observed or until 12 s (cut-off) were reached to prevent tissue damage. Three measurements were taken for each animal, and the mean paw withdrawal latency was calculated.

Cold allodynia was tested using the cold plate test (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). A constant cold stimulus at 5 °C was applied for 300 s, during which the number of hind paw lifts was recorded.

Both the contralateral and ipsilateral hind paws were assessed in all nociceptive tests.

4.4. Pharmacological Treatments

HRW was freshly generated using an HRW generator (Hydrogen, Osmo-star Soriano S.L., Alicante, Spain) at a concentration of 0.3 mM (300 µmol/L), equivalent to 0.3 µmol/mL. Accordingly, the administered doses of 0.018, 0.036, 0.075, and 0.150 µmol for a 25 g mouse, represent approximately 0.72, 1.44, 3.0, and 6.0 µmol/kg.

Given the high volatility of H2, HRW was generated individually for each animal, and immediately injected to minimize gas dissipation. In addition, the concentration of dissolved H2 was verified immediately before injection using an electrode, ensuring that the intended H2 concentration was maintained at the moment of administration.

JWH-133 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in a saline solution with 1% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and pregabalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in a saline solution (0.9% NaCl).

For the dose–response curve experiments, HRW was administered at doses of 0.018, 0.036, 0.075, and 0.150 μmol. JWH-133 at 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg obtained from a stock solution of 100 mg/kg; and pregabalin at 5, 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg obtained from a stock solution of 50 mg/kg.

Based on the dose–response curve results, 0.018 μmol of HRW was combined with 2 mg/kg of JWH-133 or 10 mg/kg of pregabalin. These doses were selected as the lowest of each drug that produced significant inhibitory effects across all tests.

The sample size calculation was performed using G*Power 3.1.7 software. Based on pilot data and assuming an α risk of 0.05 and a β risk of 0.2 in a two-tailed test, six animals per group were calculated as sufficient to detect statistically significant differences. Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used; therefore, tissues from animals subjected to behavioral testing were also utilized for Western blot analyses.

All drugs were prepared right before their use, and for each group treated with a drug, the corresponding control group received the same volume of the respective vehicle (VEH). In accordance with previous studies [

21,

29], HRW was intraperitoneally administered at 1 h before the tests. JWH-133 and pregabalin, given alone and combined with HRW, were also intraperitoneally injected in a final volume of 10 mL/kg and at 1 h prior to testing, based on previous findings [

25].

4.5. Experimental Design

In this study, a mouse model of CCI of the sciatic nerve was used. Mechanical allodynia, thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia were tested in that order at the following time points: before surgery (baseline) and at day 28 post-surgery (CCI/SHAMP) for evaluation of the effects of treatments alone and combined. After tests, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the DRG samples from SHAM and CCI mice treated with VEH, HRW, JWH-133, pregabalin, HRW plus JWH-133, and HRW plus pregabalin were obtained. Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the possible modulation of oxidative stress, inflammatory reactions, plasticity changes, and nociceptive pathways induced by these treatments.

4.6. Western Blotting

Twenty-eight days post-surgery, SHAM and CCI mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and DRG were collected and stored at −80 °C until use. DRG samples from two animals of the same group were pooled to obtain sufficient material for protein extraction and robust immunoblotting. Each pooled sample was subsequently lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), containing 1% phosphatase and 0.5% protease inhibitors, followed by sonication for 10 s. Samples were then incubated for 1 h at 4 °C to allow solubilization, and then a second sonication was performed. Afterward, samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C and 700× g, and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration of the samples was determined using the Bradford method with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein samples (60 μg) were mixed with 4× Laemmli loading buffer, denatured by heating at 95 °C, and then separated on 4% stacking/12% separating sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels using Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE by electrophoresis. Proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes for 2 h, which were blocked for 75 min with blocking buffer and then incubated overnight in agitation at 4 °C with the primary antibodies listed in

Table 2. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Subsequently, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies: anti-rabbit (1:5000) for AKT, ERK ½, GAPDH, 4-HNE, p-AKT, and p-ERK 1/2, and anti-mouse (1:5000) for NLRP3. A buffer solution consisting of either Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with Tween 20 and non-fat dry milk (5%) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (5%), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with Tween 20 and non-fat dry milk (5%) solution was used for membrane blocking, primary antibody and secondary antibody dilutions in the incubation steps. Finally, the protein bands were detected using chemiluminescence (ECL kit; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and quantified by densitometry using the ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and graphs were generated using the GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (La Jolla, CA, USA) and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; version 28, IBM, Madrid, Spain). The obtained values are presented in the graphs as mean ± standard error of mean values (SEM). The statistical approach assumptions were evaluated using Bartlett’s test for variance homogeneity and the Shapiro–Wilk test for data distribution.

Data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test when comparing two groups, such as in the validation experiments of the CCI model. Data were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when multiple groups were involved, such as in the dose–response analysis and combined treatment experiments. When the ANOVA resulted in significance, we conducted the Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test to identify differences between doses or groups. For all tests, results with a p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In the von Frey filaments and plantar tests, antinociception is expressed as the percentage of maximal possible effect, where the test latencies pre-drug (baseline) and post-drug administration are compared and calculated in accordance with the following equation:

In the cold plate test, antinociception is expressed according to the following equation:

Cutoffs of 3 g and 12 s for the mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia were employed.