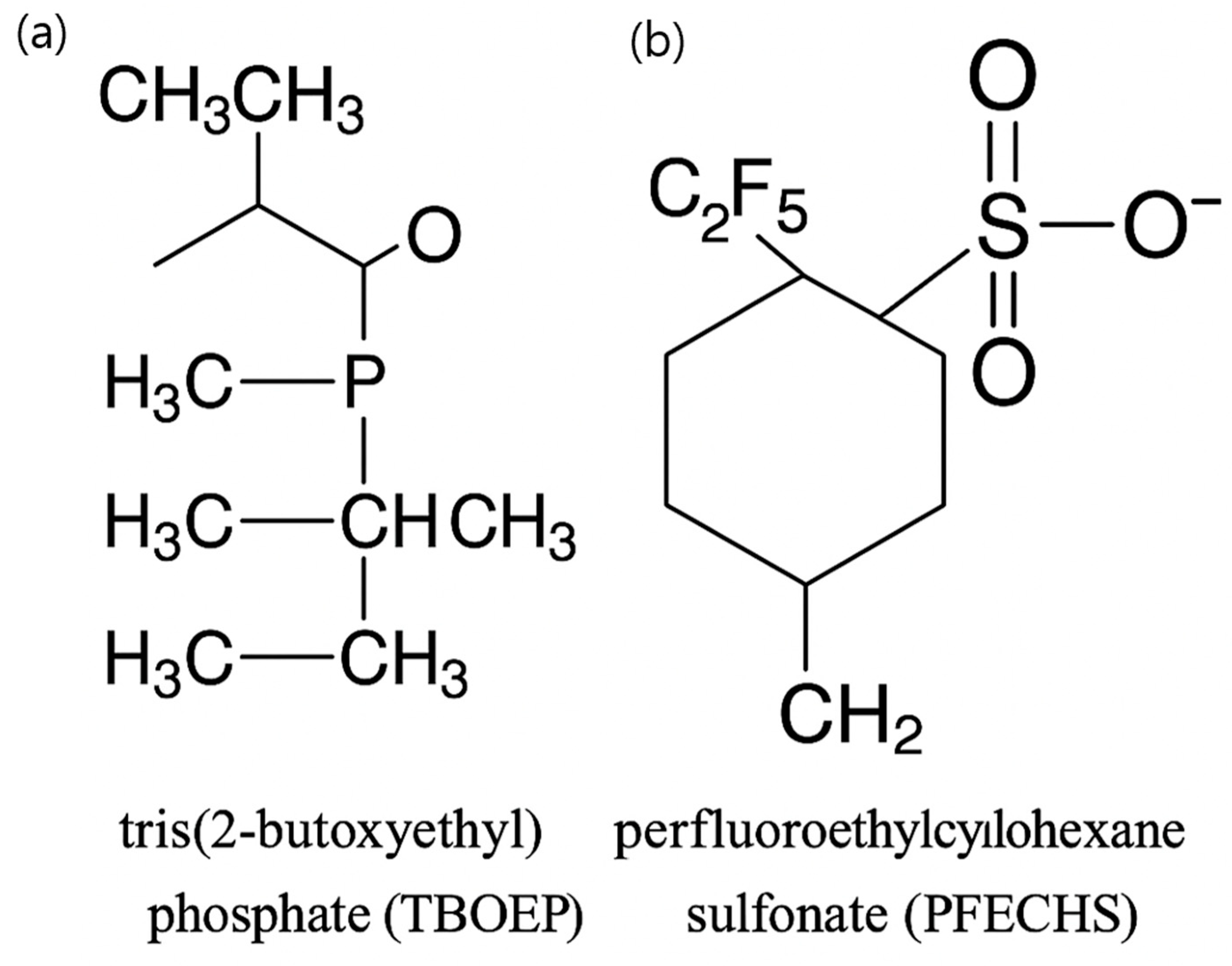

Endocrine Disruption in Freshwater Cladocerans: Transcriptomic Network Perspectives on TBOEP and PFECHS Impacts in Daphnia magna

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. TBOEP

2.1.1. TBOEP Toxicity and Transcriptomic Insights

2.1.2. GO Enrichment in TBOEP Exposure

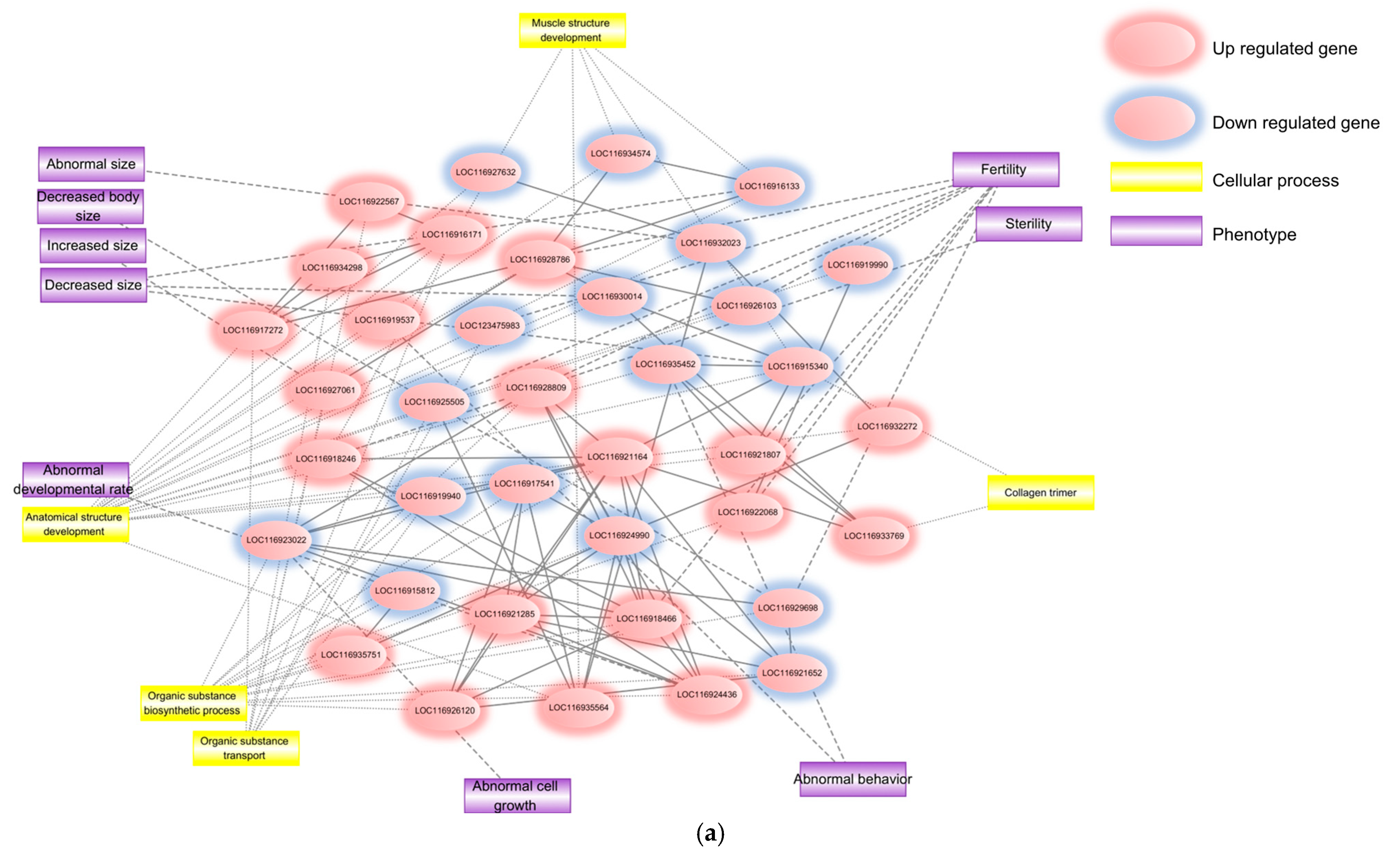

2.1.3. TBOEP Functional Network Evidence

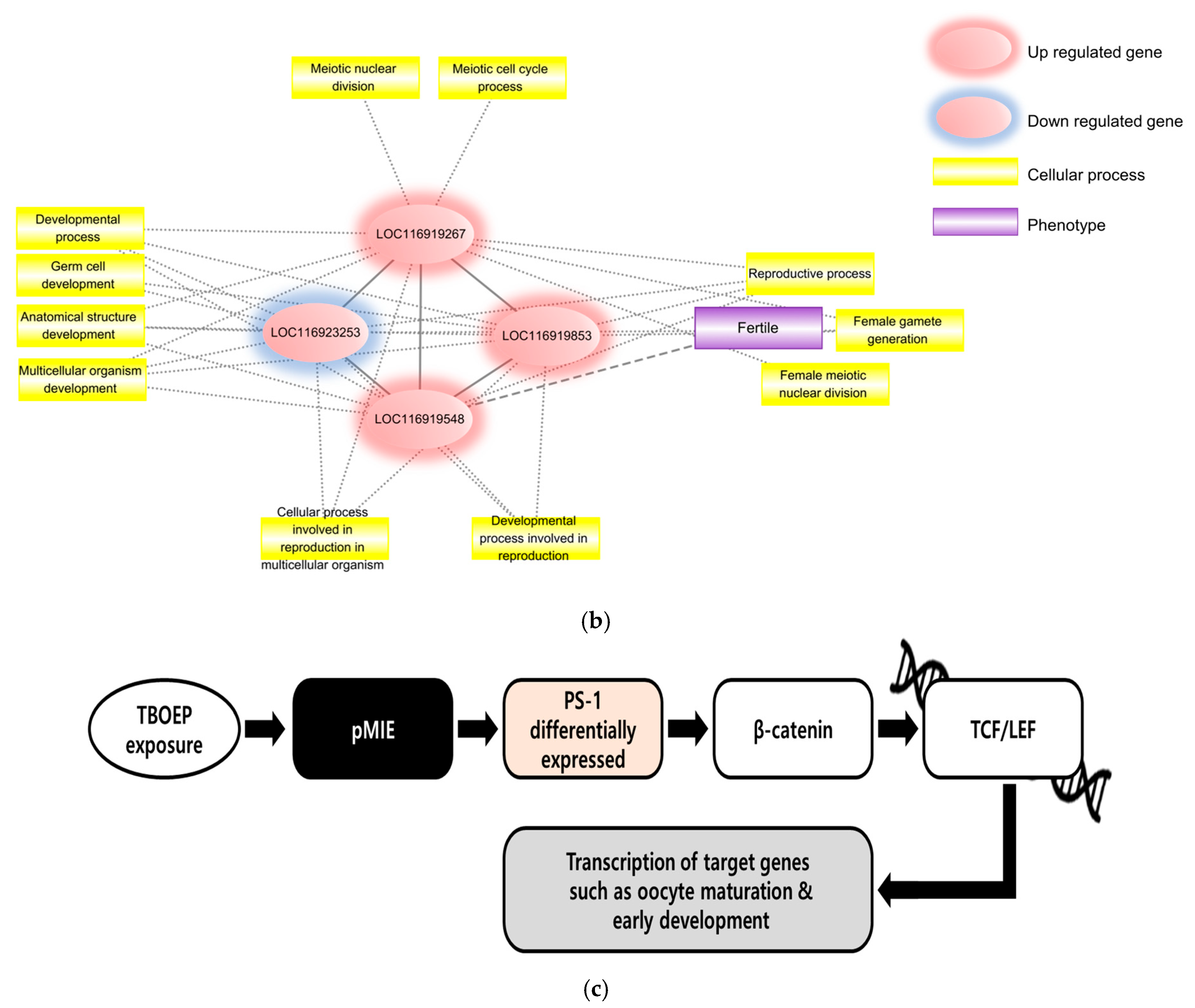

2.1.4. TBOEP Putative AOP Analysis

2.2. PFECHS

2.2.1. Transcriptomic Dataset and Overall Response

2.2.2. GO Enrichment in PFECHS Exposure

2.2.3. PFECHS Functional Network Evidence

2.2.4. PFECHS Putative AOP Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. TBOEP—Integration with Toxicological Evidence

3.2. PFECHS—Integration with Toxicological Evidence

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Transcriptomic Datasets and Preprocessing

4.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.3. Protein Interaction Networks and Hub Gene Mining

4.4. Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Inference

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Tang, J.; Yu, Y. Environmental fate and risk of organophosphate flame retardants in wastewater treatment plants: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121475. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach, R.P.; Egli, T.; Hofstetter, T.B.; von Gunten, U.; Wehrli, B. Global water pollution and human health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, P.E.; Bryan, G.W. Reproductive failure in populations of the dog whelk, Nucella lapillus, caused by imposex induced by tributyltin from antifouling paints. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 1986, 66, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, H.; Sato, T.; Song, Y.; Tollefsen, K.E.; Iguchi, T. Ecdysteroid and juvenile hormone biosynthesis, receptors and their signaling in the freshwater microcrustacean Daphnia. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 184, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, A.W.; LeBlanc, G.A. Juvenoid hormone methyl farnesoate is a sex determinant in the crustacean Daphnia magna. J. Exp. Zool. 2002, 293, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.K.M.M.; Hossain, M.F.; Uddin, M.; Khan, M.T.; Saif, U.M.; Hamed, M.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Chivers, D.P. Mechanistic insights into microplastic-induced reproductive toxicity in aquatic organisms: A comprehensive review. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 286, 107478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Gómez, A.; Brandsma, S.H.; de Boer, J.; Leonards, P.E.G. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in the aquatic environment: A review on occurrence and fate. Environ. Int. 2014, 71, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo, M.; Douville, M.; Lépine, M.; Gagnon, P.; Douville, M.; Houde, M. Multigenerational effects evaluation of the flame retardant tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBOEP) using Daphnia magna. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 190, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Wu, D.; Dang, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J. Reproduction impairment and endocrine disruption in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) after waterborne exposure to TBOEP. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 182, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vestergren, R.; Shi, Y.; Cao, D.; Xu, L.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F. Identification, Tissue Distribution, and Bioaccumulation Potential of Cyclic Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acids Isomers in an Airport Impacted Ecosystem. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10923–10932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankley, G.T.; Bennett, R.S.; Erickson, R.J.; Hoff, D.J.; Hornung, M.W.; Johnson, R.D.; Mount, D.R.; Nichols, J.W.; Russom, C.L.; Patricia, K.; et al. Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Rhee, J.S. Cadmium-induced biomarkers and adverse outcome pathway prediction in Daphnia magna revealed by transcriptome network analysis. Mol. Cell Toxicol. 2017, 13, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusse, R.; Clevers, H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 2017, 169, 985–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houde, M.; Douville, M.; Giraudo, M.; Jean, K.; Lépine, M.; Spencer, C.; De Silva, A.O. Endocrine-disruption potential of perfluoroethylcyclohexane sulfonate (PFECHS) in chronically exposed Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Test No. 211: Daphnia magna Reproduction Test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurmond, J.; Goodman, J.L.; Strelets, V.B.; Attrill, H.; Gramates, L.S.; Marygold, S.J.; Matthews, B.B.; Millburn, G.; Antonazzo, G.; Trovisco, V.; et al. FlyBase 2.0: The next generation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D759–D765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Fu, J.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, B.; Gong, Z.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Multiple bioanalytical methods reveal mechanisms of developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos/larvae exposed to tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 150, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Flatt, T.; Aguilaniu, H. Reproduction, fat metabolism, and life span: What is the connection? Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seli, E.; Babayev, E.; Collins, S.C.; Nemeth, G.; Horvath, T.L. Minireview: Metabolism of female reproduction: Regulatory mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, H.K.; Joh, H.; Yoon, Y. The cardiac physiology of Daphnia magna reveals temperature-dependent modulation of muscle contraction. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2017, 212, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffschröer, N.; Laspoumaderes, C.; Zeis, B.; Tremblay, N. Mitochondrial metabolism and respiration adjustments following temperature acclimation in Daphnia magna. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 119, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrozo, E.R.; Fowler, D.A.; Beckman, M.L. Exposure to D2-like dopamine receptor agonists inhibits swimming in Daphnia magna. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2015, 137, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valbuena, A.; López-Sánchez, I.; Lazo, P.A. Human VRK1 is an early response gene and its loss causes a block in cell cycle progression. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1642. [Google Scholar]

- González Martínez, D.; Soldevila Domenech, N.; Moltó, M.D. VRK1 is essential for early embryogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs261543. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Rotin, D. Regulation of Notch signalling by the ubiquitin ligase Mind bomb 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 14724–14734. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, M.; Kim, C.-H.; Palardy, G.; Oda, T.; Jiang, Y.-J.; Maust, D.; Yeo, S.Y.; Lorick, K.; Wright, G.J.; Ariza-McNaughton, L.; et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev. Cell 2003, 4, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, B.; Otte, K.A.; Schoppmann, K.; Hemmersbach, R.; Fröhlich, T.; Arnold, G.J.; Laforsch, C. The influence of simulated microgravity on the proteome of Daphnia magna. npj Microgravity 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, A.O.; Spencer, C.; Scott, B.F.; Backus, S.; Muir, D.C.G. Detection of a cyclic perfluorinated acid, perfluoroethylcyclohexane sulfonate, in the Great Lakes of North America. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8060–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrein, H.; Hedley, M.L.; Maniatis, T. The role of the tra2 gene in Drosophila sex determination. Cell 1994, 76, 593–606. [Google Scholar]

- Nacerddine, K.; Lehembre, F.; Bhaumik, M.; Artus, J.; Cohen-Tannoudji, M.; Babinet, C.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Dejean, A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev. Cell 2005, 9, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Schultz, R.M. Histone deacetylase 1 regulates meiotic progression in mouse oocytes. Development 2008, 135, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, I.M.; St Johnston, D.; Kiebler, M.A. eIF4AIII couples translation to mRNA localisation in Drosophila oocytes. Nature 2004, 427, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GO Term Category | Activated GO | Suppressed GO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Term | FDR | GO Term | FDR | |

| Biological process | Cellular process | 0.00018 | Biological regulation | 2.10 × 10−3 |

| Metabolic process | 0.00051 | Cellular process | 2.10 × 10−3 | |

| Organic substance metabolic process | 0.00068 | Regulation of cellular process | 1.13 × 10−2 | |

| Primary metabolic process | 0.0013 | Regulation of biological process | 0.0174 | |

| Protein metabolic process | 0.0017 | Positive regulation of transport | 0.0335 | |

| Organonitrogen compound metabolic process | 0.0017 | Positive regulation of biological process | 0.0483 | |

| Macromolecule metabolic process | 0.0017 | - | - | |

| Nitrogen compound metabolic process | 0.0017 | |||

| Protein localization | 0.0043 | |||

| Cellular localization | 0.0099 | |||

| Cellular component | Cellular anatomical entity | 1.8 × 10−13 | Cellular anatomical entity | 6.44 × 10−8 |

| Intracellular anatomical structure | 3.16 × 10−8 | Cytoplasm | 3.16 × 10−6 | |

| Cytoplasm | 1.62 × 10−7 | Intracellular anatomical structure | 1.29 × 10−5 | |

| Endomembrane system | 0.0016 | Intracellular organelle | 0.0056 | |

| Membrane-bounded organelle | 0.0018 | Membrane | 0.0072 | |

| Intracellular membrane-bounded organelle | 0.0018 | - | - | |

| Intracellular organelle | 0.0018 | |||

| Protein-containing complex | 0.0053 | |||

| Dendritic shaft | 0.0091 | |||

| Cytoplasmic vesicle | 0.0096 | |||

| Molecular function | Catalytic activity | 2.40 × 10−4 | Binding | 0.00033 |

| Protein binding | 5.70 × 10−3 | - | - | |

| Catalytic activity, acting on a protein | 3.00 × 10−2 | |||

| Hydrolase activity | 0.03 | |||

| Binding | 0.032 | |||

| Network Type | GO Term Category | GO Term | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main network | Biological process | Organic substance biosynthetic process | 1.56 × 10−2 |

| Organic substance transport | 2.21 × 10−2 | ||

| Anatomical structure development | 3.63 × 10−2 | ||

| Muscle structure development | 4.39 × 10−2 | ||

| Collagen trimer | 4.83 × 10−2 |

| GO Term Category | Activated GO | Suppressed GO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Term | FDR | GO Term | FDR | |

| Biological process | Cellular process | 9.71 × 10−17 | Cellular process | 1.98 × 10−88 |

| Metabolic process | 4.73 × 10−11 | Organic substance metabolic process | 1.95 × 10−51 | |

| Organic substance metabolic process | 9.28 × 10−10 | Metabolic process | 2.07 × 10−51 | |

| Organonitrogen compound metabolic process | 1.26 × 10−8 | Primary metabolic process | 1.23 × 10−50 | |

| Response to stimulus | 4.84 × 10−8 | Nitrogen compound metabolic process | 5.18 × 10−50 | |

| Primary metabolic process | 1.23 × 10−6 | Macromolecule metabolic process | 3.06 × 10−48 | |

| Nitrogen compound metabolic process | 1.40 × 10−5 | Cellular metabolic process | 5.02 × 10−45 | |

| Regulation of biological quality | 3.83 × 10−5 | Biological regulation | 4.19 × 10−43 | |

| Glutathione metabolic process | 6.61 × 10−5 | Cellular component organisation or biogenesis | 8.24 × 10−42 | |

| Response to ethanol | 1.10 × 10−4 | Regulation of biological process | 2.60 × 10−38 | |

| Cellular component | Cellular anatomical entity | 3.54 × 10−23 | Intracellular anatomical structure | 2.37 × 10−105 |

| Cytoplasm | 6.45 × 10−8 | Cellular anatomical entity | 1.45 × 10−96 | |

| Sarcomere | 4.75 × 10−6 | Intracellular organelle | 1.35 × 10−71 | |

| Intracellular anatomical structure | 5.18 × 10−6 | Organelle | 4.54 × 10−71 | |

| Extracellular region | 6.61 × 10−6 | Intracellular membrane-bounded organelle | 1.83 × 10−59 | |

| Supramolecular fibre | 1.10 × 10−4 | Protein-containing complex | 3.80 × 10−57 | |

| Membrane | 1.10 × 10−4 | Membrane-bounded organelle | 3.80 × 10−57 | |

| Z disc | 2.30 × 10−3 | Nucleus | 3.64 × 10−52 | |

| Organelle | 2.90 × 10−3 | Cytoplasm | 6.12 × 10−50 | |

| Intracellular organelle | 7.60 × 10−3 | Ribonucleoprotein complex | 1.14 × 10−35 | |

| Molecular function | Catalytic activity | 5.48 × 10−12 | Binding | 2.38 × 10−65 |

| Ion binding | 1.93 × 10−7 | Organic cyclic compound binding | 6.34 × 10−49 | |

| Binding | 5.32 × 10−7 | Heterocyclic compound binding | 2.18 × 10−48 | |

| Cation binding | 5.22 × 10−5 | Nucleic acid binding | 1.03 × 10−28 | |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 2.10 × 10−4 | RNA binding | 5.49 × 10−27 | |

| Glutathione transferase activity | 2.50 × 10−4 | Protein binding | 3.23 × 10−26 | |

| Metal ion binding | 3.00 × 10−4 | Ion binding | 7.42 × 10−22 | |

| Transferase activity | 6.70 × 10−4 | Catalytic activity | 1.38 × 10−20 | |

| Catalytic activity, acting on a protein | 2.50 × 10−3 | Small molecule binding | 4.93 × 10−20 | |

| Protein binding | 2.80 × 10−3 | Carbohydrate derivative binding | 6.75 × 10−20 | |

| Network Type | GO Term Category | GO Term | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main network | Biological process | Organic substance biosynthetic process | 5.44 × 10−9 |

| Developmental process | 2.60 × 10−4 | ||

| Cellular process involved in reproduction in multicellular organism | 4.60 × 10−4 | ||

| Anatomical structure development | 5.10 × 10−4 | ||

| Reproductive process | 5.60 × 10−4 | ||

| Female gamete generation | 2.50 × 10−3 | ||

| Organic substance transport | 7.50 × 10−3 | ||

| Developmental process involved in reproduction | 9.40 × 10−3 | ||

| Multicellular organism development | 1.63 × 10−2 | ||

| Meiotic cell cycle process | 1.79 × 10−2 | ||

| Germ cell development | 3.46 × 10−2 | ||

| Meiotic nuclear division | 3.88 × 10−2 | ||

| Oogenesis | 4.01 × 10−2 | ||

| Female meiotic nuclear division | 4.15 × 10−2 | ||

| Cellular component | Meiotic spindle | 1.05 × 10−2 | |

| Molecular function | Organic cyclic compound binding | 1.41 × 10−43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.W.; Yun, S.-G.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Han, J.P.; Shin, D.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, E.-M.; Seo, Y.R. Endocrine Disruption in Freshwater Cladocerans: Transcriptomic Network Perspectives on TBOEP and PFECHS Impacts in Daphnia magna. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412146

Kim HW, Yun S-G, Park JY, Lee J, Han JP, Shin DY, Lee JH, Cho E-M, Seo YR. Endocrine Disruption in Freshwater Cladocerans: Transcriptomic Network Perspectives on TBOEP and PFECHS Impacts in Daphnia magna. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412146

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyun Woo, Seok-Gyu Yun, Ju Yeon Park, Jun Lee, Jun Pyo Han, Dong Yeop Shin, Jong Hun Lee, Eun-Min Cho, and Young Rok Seo. 2025. "Endocrine Disruption in Freshwater Cladocerans: Transcriptomic Network Perspectives on TBOEP and PFECHS Impacts in Daphnia magna" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412146

APA StyleKim, H. W., Yun, S.-G., Park, J. Y., Lee, J., Han, J. P., Shin, D. Y., Lee, J. H., Cho, E.-M., & Seo, Y. R. (2025). Endocrine Disruption in Freshwater Cladocerans: Transcriptomic Network Perspectives on TBOEP and PFECHS Impacts in Daphnia magna. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412146