Decoding Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain Protein-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms in Human Uterine Fibroids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

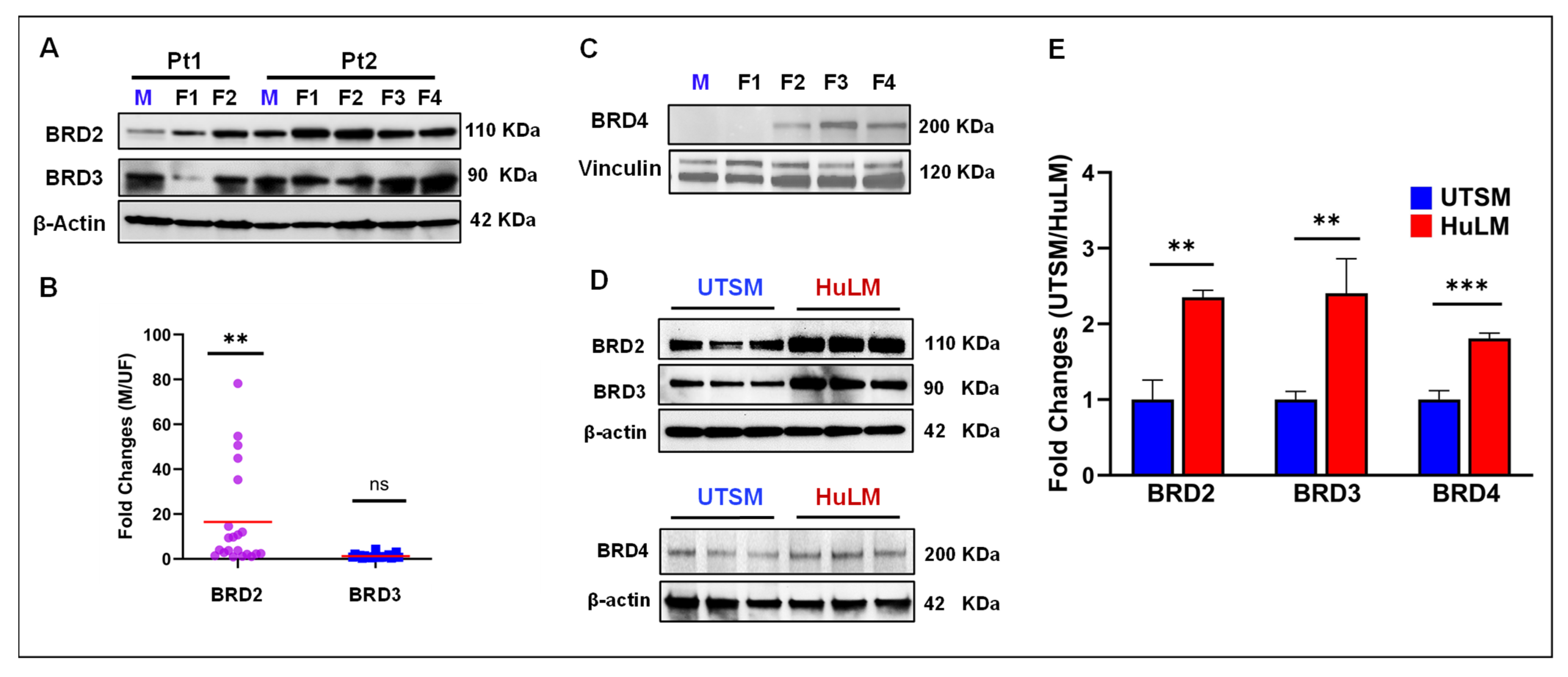

2.1. BET Proteins Are Aberrantly Upregulated in Uterine Fibroids

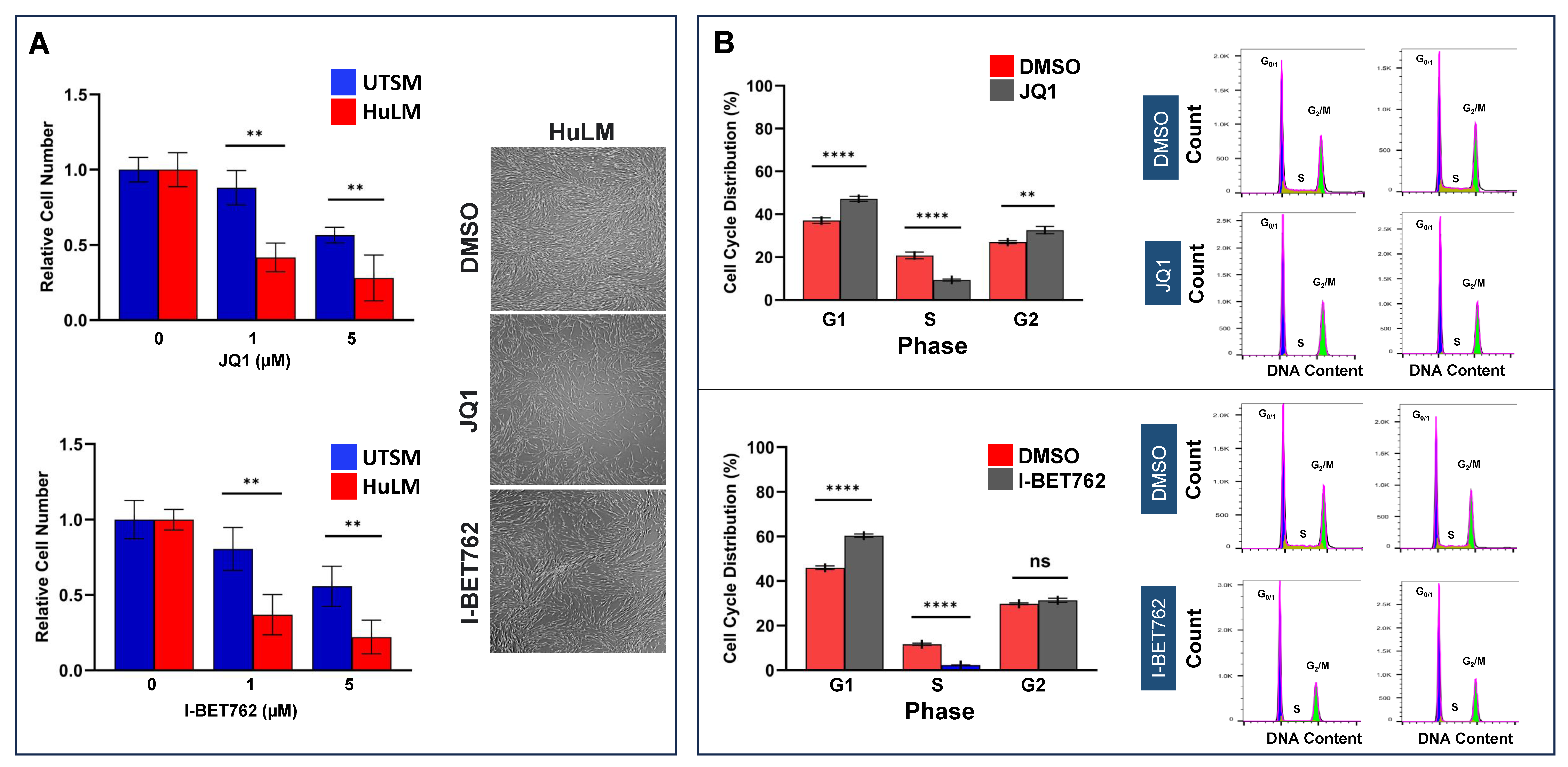

2.2. Inhibition of BET Protein Altered UF Cell Proliferation and Induced Cell Cycle Arrest

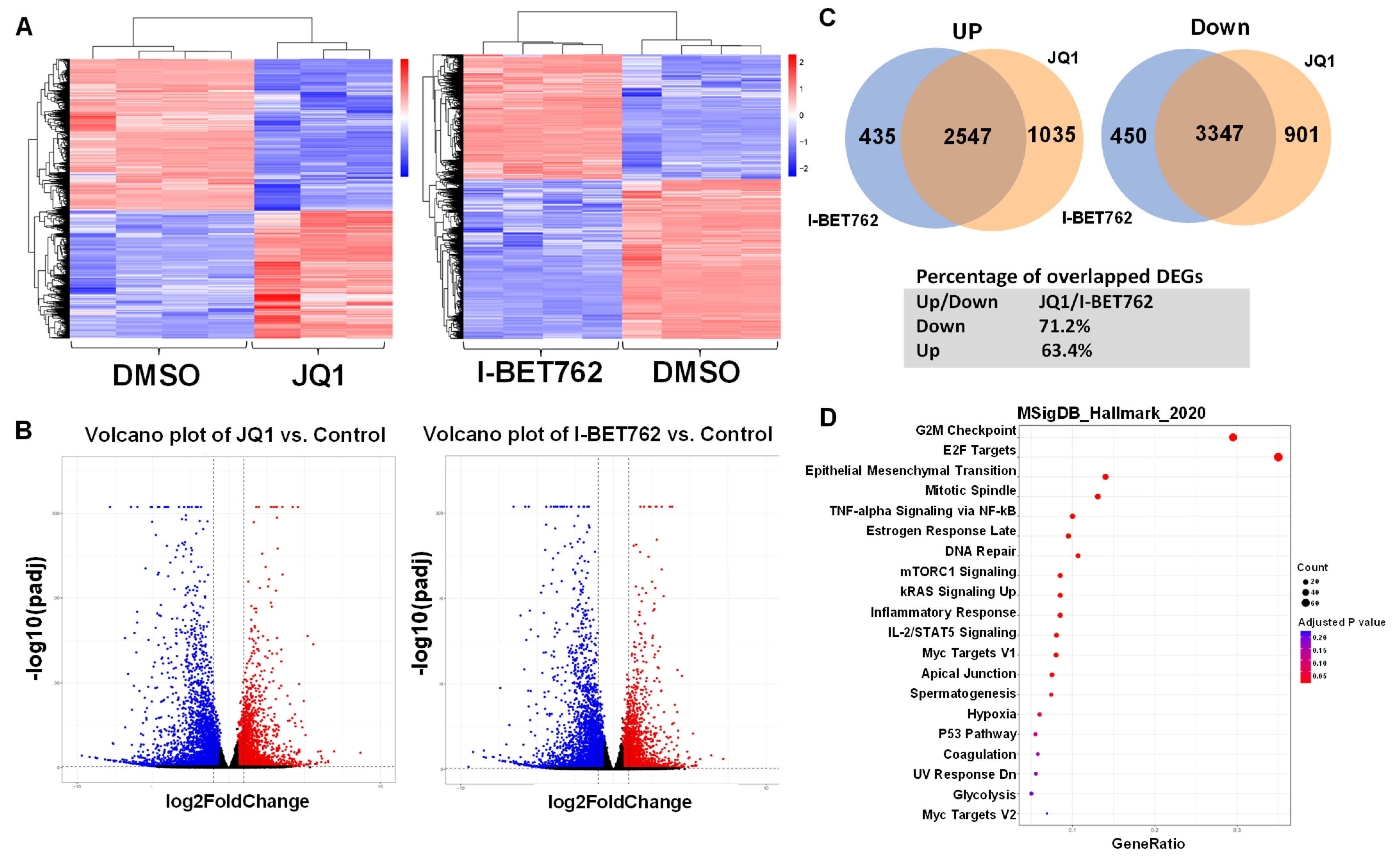

2.3. BET Proteins Inhibition Causes Extensive Changes in the UF Cell Transcriptome

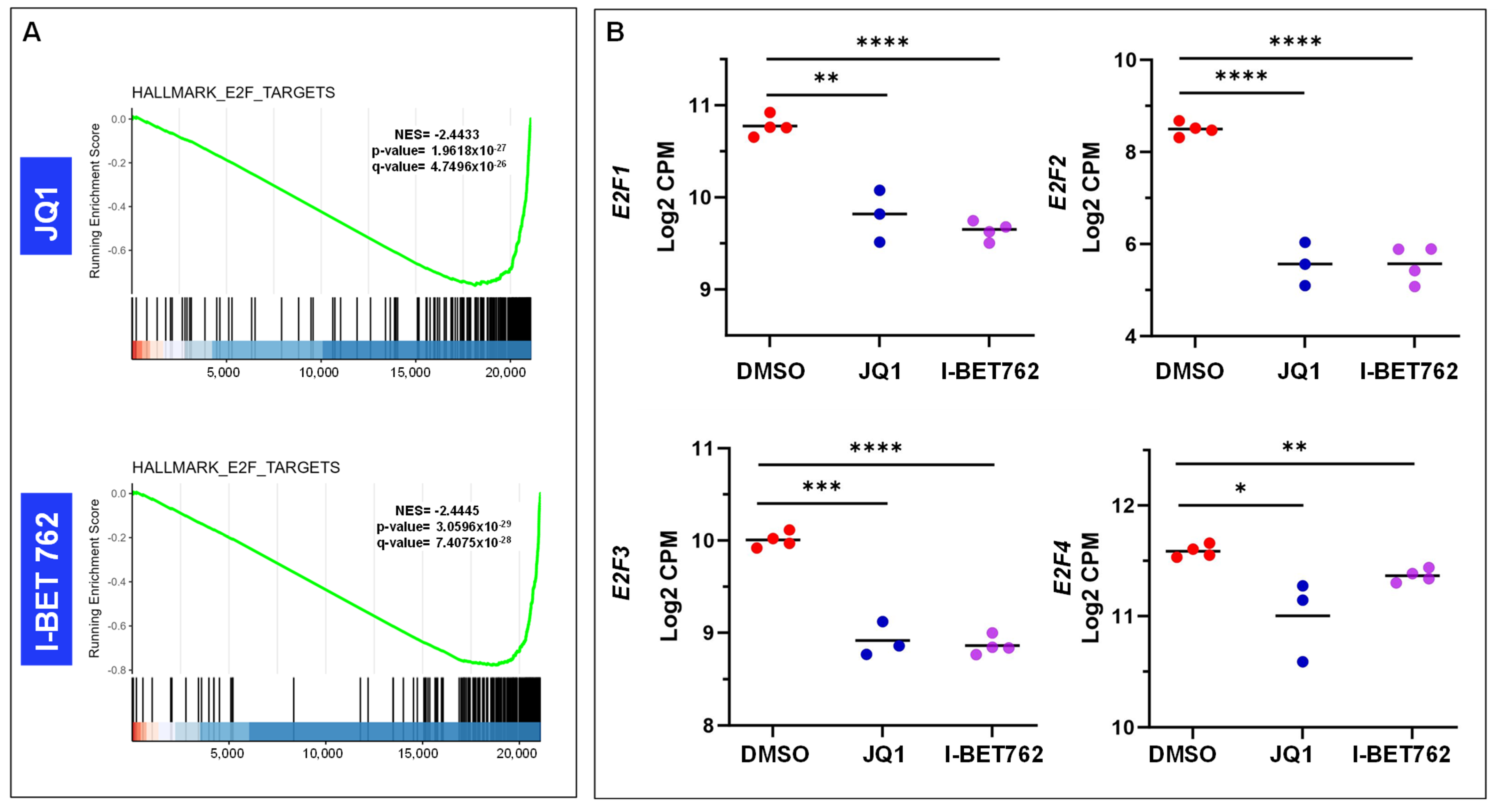

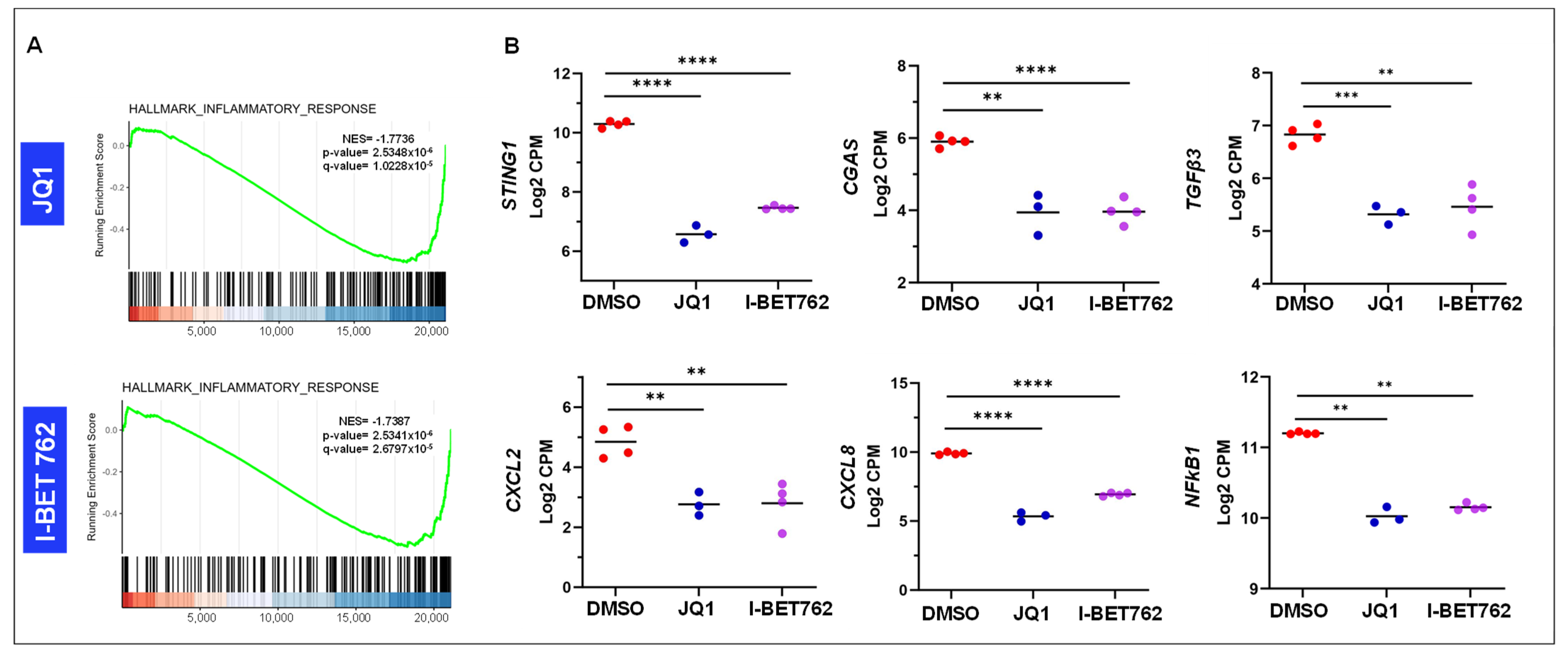

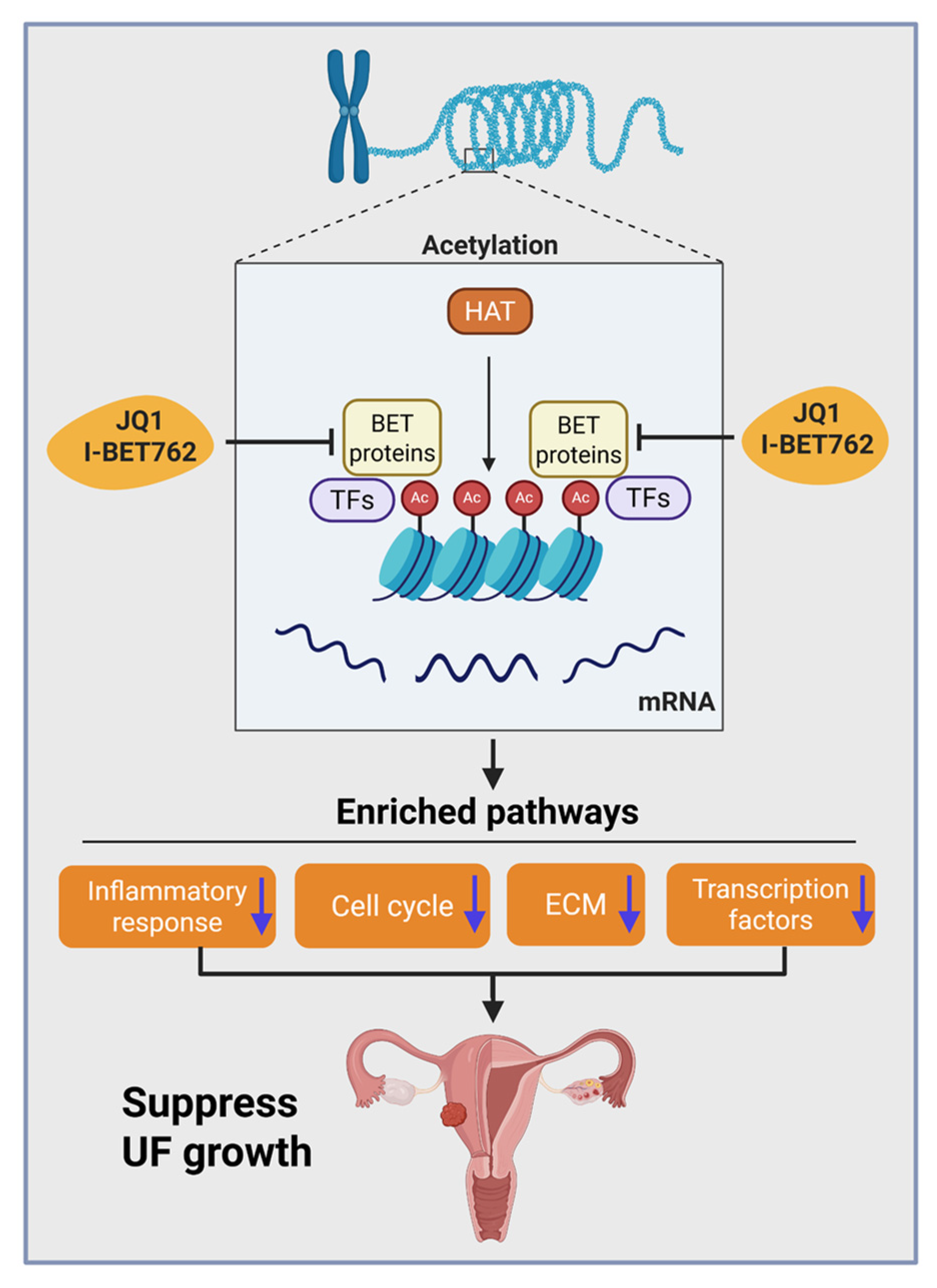

2.4. Inhibition of BET Proteins Altered Gene Expression in Multiple Biological Processes

2.5. Inhibition of BET Proteins Altered Gene Expression Associated with Epigenetic Marks

2.6. Inhibition of BET Proteins Altered the Gene Expression Correlating to Histone Modifications

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Cells and Reagents

4.3. Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analysis

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.6. Measurement of Cell Cycle Phase Distribution

4.7. RNA-Sequencing

4.8. Transcriptome Profiles Analysis

4.8.1. Transcriptome Data Analysis

4.8.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ac | Acetylation |

| BET | Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal domain |

| BETi | BET inhibitor |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BRD | Bromodomain-containing proteins 2, 3, and 4 |

| CCND1 | Cyclin D1 |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CDKN1A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) |

| CDKN1B | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27) |

| CGAS | Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase |

| COL | Collagen |

| CPM | Counts Per Million |

| CXCL | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferases |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| E2F | E2F transcription factor |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| HAT | Histone acetyltransferase |

| HuLM | Immortalized uterine fibroid (leiomyoma) cell line |

| I-BET762 | A selective BET inhibitor |

| ImageJ | Image processing and quantification software |

| JQ1 | A small molecule BET inhibitor |

| LOXL | Lysyl oxidase–like proteins |

| MKi67 | Gene encoding the Ki-67 proliferation marker |

| MSigDB | Molecular Signatures Database |

| NF-κB1 | Nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 1PCNA Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| STING1 | Stimulator of interferon genes 1 |

| TGFβ3 | Transforming growth factor beta 3 |

| UF | Uterine fibroid |

| UTSM | Immortalized uterine smooth muscle cell line |

References

- Yang, Q.; Ciebiera, M.; Victoria Bariani, M.; Ali, M.; Elkafas, H.; Boyer, T.G.; Al-Hendy, A. Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 43, 678–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulun, S.E. Uterine fibroids. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, E.A.; Laughlin-Tommaso, S.K.; Catherino, W.H.; Lalitkumar, S.; Gupta, D.; Vollenhoven, B. Uterine fibroids. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whynott, R.M.; Vaught, K.C.C.; Segars, J.H. The Effect of Uterine Fibroids on Infertility: A Systematic Review. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2017, 35, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazimeh, D.; Coco, A.; Casubhoy, I.; Segars, J.; Singh, B. The Annual Economic Burden of Uterine Fibroids in the United States (2010 Versus 2022): A Comparative Cost-Analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 3743–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Mas, A.; Diamond, M.P.; Al-Hendy, A. The Mechanism and Function of Epigenetics in Uterine Leiomyoma Development. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, D.G.; Kuisma, H.; Valimaki, N.; Raisanen, M.; Jantti, M.; Pasanen, A.; Karhu, A.; Kaukomaa, J.; Taira, A.; Cajuso, T.; et al. Deficient H2A.Z deposition is associated with genesis of uterine leiomyoma. Nature 2021, 596, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Barton, M.C. Bromodomain Histone Readers and Cancer. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G.E.; Mayer, A.; Buckley, D.L.; Erb, M.A.; Roderick, J.E.; Vittori, S.; Reyes, J.M.; di Iulio, J.; Souza, A.; Ott, C.J.; et al. BET Bromodomain Proteins Function as Master Transcription Elongation Factors Independent of CDK9 Recruitment. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 5–18.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhou, B.; Yang, C.Y.; Ji, J.; McEachern, D.; Przybranowski, S.; Jiang, H.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Targeted Degradation of BET Proteins in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2476–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picaud, S.; Leonards, K.; Lambert, J.P.; Dovey, O.; Wells, C.; Fedorov, O.; Monteiro, O.; Fujisawa, T.; Wang, C.Y.; Lingard, H.; et al. Promiscuous targeting of bromodomains by bromosporine identifies BET proteins as master regulators of primary transcription response in leukemia. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeta, S.; Lui, G.Y.L.; Shaw, R.; Moser, R.; Gurley, K.E.; Durenberger, G.; Rosati, R.; Diaz, R.L.; Ince, T.A.; Swisher, E.M.; et al. Targeting BET Proteins BRD2 and BRD3 in Combination with PI3K-AKT Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy for Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, P.K.; Herner, A.; Mello, S.S.; Wirth, M.; Hausmann, S.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Lofgren, S.M.; Kuschma, T.; Hahn, S.A.; Vangala, D.; et al. Combined inhibition of BET family proteins and histone deacetylases as a potential epigenetics-based therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1163–1171, Erratum in Nat Med. 2024, 30, 2090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03054-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faivre, E.J.; McDaniel, K.F.; Albert, D.H.; Mantena, S.R.; Plotnik, J.P.; Wilcox, D.; Zhang, L.; Bui, M.H.; Sheppard, G.S.; Wang, L.; et al. Selective inhibition of the BD2 bromodomain of BET proteins in prostate cancer. Nature 2020, 578, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilan, O.; Rioja, I.; Knezevic, K.; Bell, M.J.; Yeung, M.M.; Harker, N.R.; Lam, E.Y.N.; Chung, C.W.; Bamborough, P.; Petretich, M.; et al. Selective targeting of BD1 and BD2 of the BET proteins in cancer and immunoinflammation. Science 2020, 368, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, M.; Capparelli, C.; Erkes, D.A.; Purwin, T.J.; Heilman, S.A.; Berger, A.C.; Davies, M.A.; Aplin, A.E. Targeting BRD/BET proteins inhibits adaptive kinome upregulation and enhances the effects of BRAF/MEK inhibitors in melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, H.G.; El-Gamal, D.; Powell, B.; Hing, Z.A.; Blachly, J.S.; Harrington, B.; Mitchell, S.; Grieselhuber, N.R.; Williams, K.; Lai, T.H.; et al. BRD4 Profiling Identifies Critical Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Oncogenic Circuits and Reveals Sensitivity to PLX51107, a Novel Structurally Distinct BET Inhibitor. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.S.; Williams, C.R.; Royce, D.B.; Pioli, P.A.; Sporn, M.B.; Liby, K.T. Bromodomain inhibitors, JQ1 and I-BET 762, as potential therapies for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017, 394, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Deng, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. General mechanism of JQ1 in inhibiting various types of cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Ciavattini, A.; Petraglia, F.; Castellucci, M.; Ciarmela, P. Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: A potential target for future therapeutics. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Afrin, S.; Singh, B.; Jayes, F.L.; Brennan, J.T.; Borahay, M.A.; Leppert, P.C.; Segars, J.H. Extracellular matrix and Hippo signaling as therapeutic targets of antifibrotic compounds for uterine fibroids. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaluddin, M.F.B.; Nahar, P.; Tanwar, P.S. Proteomic Characterization of the Extracellular Matrix of Human Uterine Fibroids. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 2656–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Al-Hendy, A. Update on the Role and Regulatory Mechanism of Extracellular Matrix in the Pathogenesis of Uterine Fibroids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppert, P.C.; Jayes, F.L.; Segars, J.H. The extracellular matrix contributes to mechanotransduction in uterine fibroids. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2014, 2014, 783289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Falahati, A.; Khosh, A.; Vafaei, S.; Al-Hendy, A. Targeting Bromodomain-Containing Protein 9 in Human Uterine Fibroid Cells. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 32, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Vafaei, S.; Falahati, A.; Khosh, A.; Bariani, M.V.; Omran, M.M.; Bai, T.; Siblini, H.; Ali, M.; He, C.; et al. Bromodomain-Containing Protein 9 Regulates Signaling Pathways and Reprograms the Epigenome in Immortalized Human Uterine Fibroid Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, S.A.; Robinson, M.D.; Strbenac, D.; Statham, A.L.; Song, J.Z.; Hulf, T.; Sutherland, R.L.; Coolen, M.W.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S.J. Regional activation of the cancer genome by long-range epigenetic remodeling. Cancer Cell. 2013, 23, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrump, D.S.; Hong, J.A.; Nguyen, D.M. Utilization of chromatin remodeling agents for lung cancer therapy. Cancer J. 2007, 13, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J. Bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitors (BETi) for cancer therapy: Chemical modulation of chromatin structure. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a018663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Daoud, A.; Eblen, S.T. Targeting Chromatin Remodeling for Cancer Therapy. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, L.; Stoeck, A.; Zhang, X.; Lanczky, A.; Mirabella, A.C.; Wang, T.L.; Gyorffy, B.; Lupien, M. Genome-wide reprogramming of the chromatin landscape underlies endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1490–E1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magic, Z.; Supic, G.; Brankovic-Magic, M. Towards targeted epigenetic therapy of cancer. J. BUON 2009, 14, S79–S88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Casson, A.G. Epigenetic aberrations and targeted epigenetic therapy of esophageal cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2008, 8, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Cao, D.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, K. Genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity of epithelial ovarian cancer and the clinical implications for molecular targeted therapy. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimamura, T.; Chen, Z.; Soucheray, M.; Carretero, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Tchaicha, J.H.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, K.A.; Cohoon, T.J.; Qi, J.; et al. Efficacy of BET bromodomain inhibition in Kras-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6183–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.E.; Yoo, M.; Lee, H.K.; Lee, C.O.; Yoo, M.; Jung, K.Y.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.U.; et al. Novel brd4 inhibitors with a unique scaffold exhibit antitumor effects. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck-Brentano, E.; Vizlin-Hodzic, D.; Nilsson, J.A.; Nilsson, L.M. BET bromodomain inhibitor HMBA synergizes with MEK inhibition in treatment of malignant glioma. Epigenetics 2021, 16, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Y.Y.; Lyv, X.; Zhou, Q.J.; Xiang, Z.; Stanford, D.; Bodduluri, S.; Rowe, S.M.; Thannickal, V.J. Brd4-p300 inhibition downregulates Nox4 and accelerates lung fibrosis resolution in aged mice. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e137127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Benham, V.; Jdanov, V.; Bullard, B.; Leal, A.S.; Liby, K.T.; Bernard, J.J. A BET Bromodomain Inhibitor Suppresses Adiposity-Associated Malignant Transformation. Cancer Prev. Res. 2018, 11, 129–142, Erratum in Cancer Prev. Res. 2020, 13, 977. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Jackson, A.L.; Kilgore, J.E.; Zhong, Y.; Chan, L.L.; Gehrig, P.A.; Zhou, C.; Bae-Jump, V.L. JQ1 suppresses tumor growth through downregulating LDHA in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 6915–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipooya, S.; Zarezadeh, R.; Latifi, Z.; Nouri, M.; Fattahi, A.; Salemi, Z. Serum transforming growth factor beta and leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 as potential biomarkers for diagnosis of uterine leiomyomas. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciebiera, M.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Wrzosek, M.; Meczekalski, B.; Nowicka, G.; Lukaszuk, K.; Ciebiera, M.; Slabuszewska-Jozwiak, A.; Jakiel, G. Role of Transforming Growth Factor beta in Uterine Fibroid Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T.D.; Malik, M.; Britten, J.; Parikh, T.; Cox, J.; Catherino, W.H. Ulipristal acetate decreases active TGF-beta3 and its canonical signaling in uterine leiomyoma via two novel mechanisms. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 806–815.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norian, J.M.; Malik, M.; Parker, C.Y.; Joseph, D.; Leppert, P.C.; Segars, J.H.; Catherino, W.H. Transforming growth factor beta3 regulates the versican variants in the extracellular matrix-rich uterine leiomyomas. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkina, A.C.; Nikolajczyk, B.S.; Denis, G.V. BET protein function is required for inflammation: Brd2 genetic disruption and BET inhibitor JQ1 impair mouse macrophage inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3670–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y. Epigenetic cross-talk between DNA methylation and histone modifications in human cancers. Yonsei Med. J. 2009, 50, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Fischle, W. Epigenetic markers and their cross-talk. Essays Biochem. 2010, 48, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulwach, K.E.; Li, X.; Smrt, R.D.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Lin, L.; Santistevan, N.J.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Jin, P. Cross talk between microRNA and epigenetic regulation in adult neurogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Song, Y.; Lam, R.; Ruder, D.; Creighton, C.J.; Bid, H.K.; Bill, K.L.; Bolshakov, S.; Zhang, X.; Lev, D.; et al. HDAC Inhibition for the Treatment of Epithelioid Sarcoma: Novel Cross Talk Between Epigenetic Components. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, D.; King, J.; Xu, Y.; Liang, F.S. Investigating crosstalk between H3K27 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation in CRISPR/dCas-based epigenome editing and gene activation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Nair, S.; Laknaur, A.; Ismail, N.; Diamond, M.P.; Al-Hendy, A. The Polycomb Group Protein EZH2 Impairs DNA Damage Repair Gene Expression in Human Uterine Fibroids. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Elam, L.; Laknaur, A.; Gavrilova-Jordan, L.; Lue, J.; Diamond, M.P.; Al-Hendy, A. Altered DNA repair genes in human uterine fibroids are epigenetically regulated via EZH2 histone methyltransferase. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrow, J.; Frankish, A.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Tapanari, E.; Diekhans, M.; Kokocinski, F.; Aken, B.L.; Barrell, D.; Zadissa, A.; Searle, S.; et al. GENCODE: The reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | Sequence | F or R | Assay | Species | Amplicon Size (bp) | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRD2 | GCCCATGAGTTACGATGAGAAG | F | q-PCR | Human | 101 | NM_005104.4 |

| BRD2 | GCTCCCTGGCTTGGATTATATG | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| BRD3 | AACCACTTCCCGAGCTTATG | F | q-PCR | Human | 118 | NM_007371.4 |

| BRD3 | TCTCTGCGACTGTGTGAATG | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| BRD4 | GAAGACTCCGAAACAGAGATGG | F | q-PCR | Human | 93 | AF386649.1 |

| BRD4 | CTGCTGATGGTGGTGATGAT | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| PCNA | GGACACTGCTGGTGGTATTT | F | q-PCR | Human | 105 | J04718 |

| PCNA | CAGAACTGGTGGAGGGTAAAC | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| CCND1 | GGGTTGTGCTACAGATGATAGAG | F | q-PCR | Human | 112 | NM-053056.3 |

| CCND1 | AGACGCCTCCTTTGTGTTAAT | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| CDK1 | TCAGTCTTCAGGATGTGCTTATG | F | q-PCR | Human | 107 | NM_001786.5 |

| CDK1 | GTACTGACCAGGAGGGATAGAA | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| STING1 | GGTGCCTGATAACCTGAGTATG | F | q-PCR | Human | 103 | NM_198282.4 |

| STING1 | GCTGTAAACCCGATCCTTGA | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| SIRT1 | AGAACCCATGGAGGATGAAAG | F | q-PCR | Human | 111 | AF083106.2 |

| SIRT1 | TCATCTCCATCAGTCCCAAATC | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| DNMT3A | CTGAGGTAGCGACACAAAGTTA | F | q-PCR | Human | 101 | NM_175629.2 |

| DNMT3A | CTCTTCTGGGTGCTGATACTTC | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| DNMT1 | CGGCCTCATCGAGAAGAATATC | F | q-PCR | Human | 95 | NM_001130823.3 |

| DNMT1 | TGCCATTAACACCACCTTCA | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| NF-kB | GTGACAGGAGACGTGAAGATG | F | q-PCR | Human | 104 | NM_003998.4 |

| NF-kB | TGAAGGTGGATGATTGCTAAGT | R | q-PCR | Human | ||

| 18S | CACGGACAGGATTGACAGATT | F | q-PCR | Human | 119 | NR_145820 |

| 18S | GCCAGAGTCTCGTTCGTTATC | R | q-PCR | Human |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Q.; Vafaei, S.; Falahati, A.; Khosh, A.; Omran, M.M.; Bai, T.; Bariani, M.V.; Ali, M.; Boyer, T.G.; Al-Hendy, A. Decoding Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain Protein-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms in Human Uterine Fibroids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412144

Yang Q, Vafaei S, Falahati A, Khosh A, Omran MM, Bai T, Bariani MV, Ali M, Boyer TG, Al-Hendy A. Decoding Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain Protein-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms in Human Uterine Fibroids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412144

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Qiwei, Somayeh Vafaei, Ali Falahati, Azad Khosh, Mervat M. Omran, Tao Bai, Maria Victoria Bariani, Mohamed Ali, Thomas G. Boyer, and Ayman Al-Hendy. 2025. "Decoding Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain Protein-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms in Human Uterine Fibroids" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412144

APA StyleYang, Q., Vafaei, S., Falahati, A., Khosh, A., Omran, M. M., Bai, T., Bariani, M. V., Ali, M., Boyer, T. G., & Al-Hendy, A. (2025). Decoding Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal Domain Protein-Mediated Epigenetic Mechanisms in Human Uterine Fibroids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412144