Pig Genome Editing for Agriculture: Achievements and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Main Achievements and Challenges in Pig Agricultural Genetics

2.1. Meat Quality and Productivity

2.2. Hereditary Diseases

2.3. Infectious Diseases

2.4. Polygenic Diseases

2.5. Boar Taint

2.6. Introduction of Foreign Genes

3. Principles of Pig Genome Manipulations

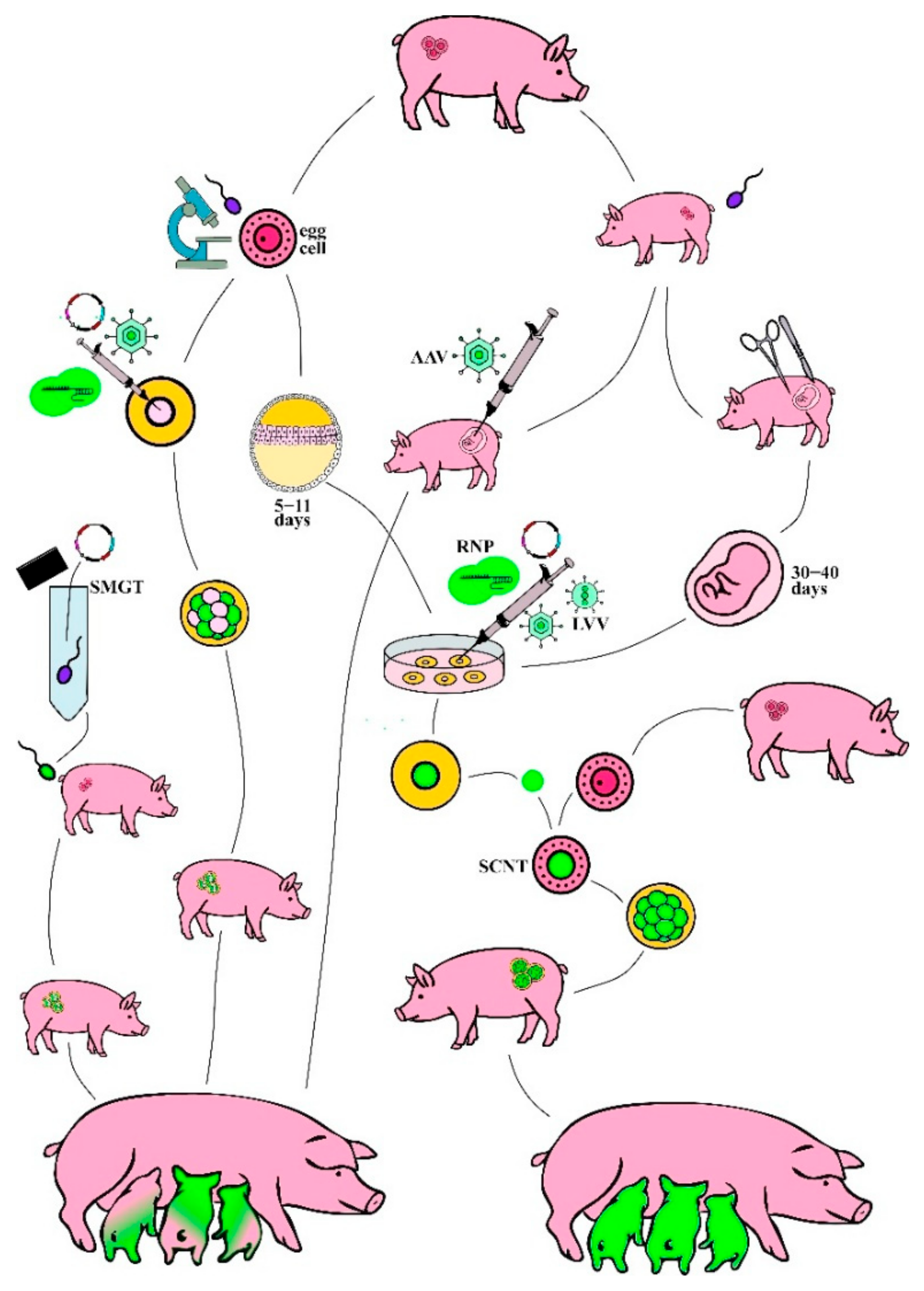

4. Delivery Platforms for Molecular Tools

4.1. Delivery Platforms Initially Designed for Genetic Engineering

4.2. The Era of Genome Editing

4.3. New Genome Editing Technologies

5. Application of Genome Editing to Improve Agricultural Traits in Pig

5.1. Virus Resistance

5.2. Increased Productivity

5.3. Temperature Sensitivity

5.4. Knock-In

6. Remaining Challenges and Opportunities in Pig Genome Editing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Li, D. Invited Review—Current Status, Challenges and Prospects for Pig Production in Asia. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, G.G.; Corrales, N.L.; Talegón, G.; Aguirre, L. Invited Review—Pig Meat Production in the European Union-27: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Trends. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-139255-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrosemoli, S.; Tang, C. Animal Welfare and Production Challenges Associated with Pasture Pig Systems: A Review. Agriculture 2020, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delsart, M.; Pol, F.; Dufour, B.; Rose, N.; Fablet, C. Pig Farming in Alternative Systems: Strengths and Challenges in Terms of Animal Welfare, Biosecurity, Animal Health and Pork Safety. Agriculture 2020, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenen, M.A.M.; Archibald, A.L.; Uenishi, H.; Tuggle, C.K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Rothschild, M.F.; Rogel-Gaillard, C.; Park, C.; Milan, D.; Megens, H.-J.; et al. Analyses of Pig Genomes Provide Insight into Porcine Demography and Evolution. Nature 2012, 491, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mote, B.E.; Rothschild, M.F. Modern Genetic and Genomic Improvement of the Pig. In Animal Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 249–262. ISBN 978-0-12-817052-6. [Google Scholar]

- Groenen, M.A.M. A Decade of Pig Genome Sequencing: A Window on Pig Domestication and Evolution. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2016, 48, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, A.; Affara, N.; Aken, B.; Beiki, H.; Bickhart, D.M.; Billis, K.; Chow, W.; Eory, L.; Finlayson, H.A.; Flicek, P.; et al. An Improved Pig Reference Genome Sequence to Enable Pig Genetics and Genomics Research. GigaScience 2020, 9, giaa051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Prado, J.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Wang, D.; Villanueva-García, D.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Mora-Medina, P.; Hernández-Avalos, I.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; et al. Thermoregulation Mechanisms and Perspectives for Validating Thermal Windows in Pigs with Hypothermia and Hyperthermia: An Overview. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1023294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Gustafson, U.; Andersson, L. The Uncoupling Protein 1 Gene (UCP1) Is Disrupted in the Pig Lineage: A Genetic Explanation for Poor Thermoregulation in Piglets. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, J.K.; Van Goor, A.; Walker, K.E.; Hailstock, T.; Franklin, J.; Dai, C. Importance of the Pig as a Human Biomedical Model. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, A.; Walenia, A. Native Pig Breeds as a Source of Biodiversity—Breeding and Economic Aspects. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsegge, I.; Calus, M.; Hoving-Bolink, R.; Lopes, M.; Megens, H.-J.; Oldenbroek, K. Impact of Merging Commercial Breeding Lines on the Genetic Diversity of Landrace Pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2019, 51, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Tarafdar, A.; Gaur, G.K.; Jadhav, S.E.; Tiwari, R.; Dutt, T. (Eds.) Commercial Pig Farming: A Guide for Swine Production and Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Ma, H.; Huo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, D. CRISPR Technology Acts as a Dual-Purpose Tool in Pig Breeding: Enhancing Both Agricultural Productivity and Biomedical Applications. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Escriche, N.; Forni, S.; Noguera, J.L.; Varona, L. Genomic Information in Pig Breeding: Science Meets Industry Needs. Livest. Sci. 2014, 166, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.P.; Kiefer, C.; Ullmann, L.S.; da Rocha, G.H.; Andrade, G.L.; Teixeira, S.A. Molecular markers and their importance for pig production and breeding: An overview. Cad. Pedagóg. 2024, 21, e8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A.; Lowe, J. Pigs and Chips: The Making of a Biotechnology Innovation Ecosystem. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2022, 36, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, D.B.; Español, L.Á.; Figueroa, C.E.; Marini, S.J.; Mac Allister, M.E.; Carpinetti, B.N.; Fernández, G.P.; Merino, M.L. Wild Pigs (Sus Scrofa) Population as Reservoirs for Deleterious Mutations in the RYR1 Gene Associated with Porcine Stress Syndrome. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2021, 11, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Xie, X.; Wu, Z.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, M.; Ma, J.; et al. Muscle Glycogen Level and Occurrence of Acid Meat in Commercial Hybrid Pigs Are Regulated by Two Low-Frequency Causal Variants with Large Effects and Multiple Common Variants with Small Effects. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2019, 51, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yin, Y.; Xu, K.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J. Knockdown of LGALS12 Inhibits Porcine Adipocyte Adipogenesis via PKA–Erk1/2 Signaling Pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2018, 50, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xing, Y.; Xu, P.; Yang, Q.; Qiao, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Ren, J.; Huang, L. Dissection of the Genetic Mechanisms Underlying Congenital Anal Atresia in Pigs. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, M.F.L.; Harlizius, B.; Lopes, M.S.; Greijdanus-van Der Putten, S.W.M.; Dibbits, B.; Laport, K.; Megens, H.-J.; Groenen, M.A.M. Detection of a Frameshift Deletion in the SPTBN4 Gene Leads to Prevention of Severe Myopathy and Postnatal Mortality in Pigs. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.; Röntgen, M.; Maak, S. Congenital Splay Leg Syndrome in Piglets—Current Knowledge and a New Approach to Etiology. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 609883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Chakravarty, A.K. Disease resistance for different livestock species. In Genetics and Breeding for Disease Resistance of Livestock; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Ewen, C.L.; Trible, B.R.; Kerrigan, M.A.; Cino-Ozuna, A.G.; Samuel, M.S.; Lightner, J.E.; McLaren, D.G.; Mileham, A.J.; et al. Gene-Edited Pigs Are Protected from Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yoo, D. PRRS Virus Receptors and Their Role for Pathogenesis. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 177, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Dunkelberger, J.; Lim, K.-S.; Lunney, J.K.; Tuggle, C.K.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Dekkers, J.C.M. Associations of Natural Variation in the CD163 and Other Candidate Genes on Host Response of Nursery Pigs to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Infection. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltes, J.E.; Fritz-Waters, E.; Eisley, C.J.; Choi, I.; Bao, H.; Kommadath, A.; Serão, N.V.L.; Boddicker, N.J.; Abrams, S.M.; Schroyen, M.; et al. Identification of a Putative Quantitative Trait Nucleotide in Guanylate Binding Protein 5 for Host Response to PRRS Virus Infection. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, A.; Nazki, S.; Jeong, C.-G.; Gu, S.; Mattoo, S.U.S.; Lee, S.-I.; Yang, M.-S.; Lim, B.; Kim, K.-S.; Kim, B.; et al. Effect of Polymorphisms in Porcine Guanylate-Binding Proteins on Host Resistance to PRRSV Infection in Experimentally Challenged Pigs. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, M.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Gorjanc, G.; Campbell, M.A.; Naswa, S.; Kelly, K.; Lightner, J.; Rounsley, S.; Hickey, J.M. Sequence Variation, Evolutionary Constraint, and Selection at the CD163 Gene in Pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2018, 50, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Qiao, J.; Fu, Q.; Chen, C.; Ni, W.; Wujiafu, S.; Ma, S.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, J.; Wang, P.; et al. Transgenic shRNA Pigs Reduce Susceptibility to Foot and Mouth Disease Virus Infection. eLife 2015, 4, e06951, Correction in eLife 2016, 5, e14281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-E. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea: Insights and Progress on Vaccines. Vaccines 2024, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Green, J.A.; Redel, B.K.; Geisert, R.D.; Lee, K.; Telugu, B.P.; Wells, K.D.; Prather, R.S. Improvements in Pig Agriculture through Gene Editing. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dräger, C.; Beer, M.; Blome, S. Porcine Complement Regulatory Protein CD46 and Heparan Sulfates Are the Major Factors for Classical Swine Fever Virus Attachment in vitro. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, C.; Pang, D.; Yang, K.; Jiao, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, C.; Hu, L.; Li, F.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; et al. Generation of PCBP1-Deficient Pigs Using CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing. iScience 2022, 25, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isken, O.; Postel, A.; Bruhn, B.; Lattwein, E.; Becher, P.; Tautz, N. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knockout of DNAJC14 Verifies This Chaperone as a Pivotal Host Factor for RNA Replication of Pestiviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01714-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, E.; Temeeyasen, G.; Piñeyro, P.E. Comprehensive Review on Immunopathogenesis, Diagnostic and Epidemiology of Senecavirus A. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.R.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Stoian, A.M.; Petrovan, V.; Sheahan, M.; Ganta, C.; Cino-Ozuna, G.; Kim, D.Y.; Dunleavey, J.M.; Whitworth, K.M.; et al. Disruption of Anthrax Toxin Receptor 1 in Pigs Leads to a Rare Disease Phenotype and Protection from Senecavirus A Infection. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Artiaga, B.L.; McDowell, C.D.; Whitworth, K.M.; Wells, K.D.; Prather, R.S.; Delhon, G.; Cigan, M.; White, S.N.; Retallick, J.; et al. Gene Editing of Pigs to Control Influenza A Virus Infections. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2387449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci Zanella, G.; Snyder, C.A.; Arruda, B.L.; Whitworth, K.; Green, E.; Poonooru, R.R.; Telugu, B.P.; Baker, A.L. Pigs Lacking TMPRSS2 Displayed Fewer Lung Lesions and Reduced Inflammatory Response When Infected with Influenza A Virus. Front. Genome Ed. 2024, 5, 1320180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Brenig, B.; Winnacker, E.-L.; Brem, G. Transgenic Pigs Carrying cDNA Copies Encoding the Murine Mx1 Protein Which Confers Resistance to Influenza Virus Infection. Gene 1992, 121, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, H. Resistance to Pseudorabies Virus by Knockout of Nectin1/2 in Pig Cells. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 2837–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisimwa, P.N.; Ongus, J.R.; Tonui, R.; Bisimwa, E.B.; Steinaa, L. Resistance to African Swine Fever Virus among African Domestic Pigs Appears to Be Associated with a Distinct Polymorphic Signature in the RelA Gene and Upregulation of RelA Transcription. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgrave, C.J.; Gilmour, L.; Lowden, C.S.; Lillico, S.G.; Mellencamp, M.A.; Whitelaw, C.B.A. Species-Specific Variation in RELA Underlies Differences in NF-κB Activity: A Potential Role in African Swine Fever Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6008–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Bao, M.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. CD1d Facilitates African Swine Fever Virus Entry into the Host Cells via Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2220575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.-I.; Lee, Y.-M. Early Events in Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection: Viral Entry. Pathogens 2018, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, H.; Xiao, T.; Wang, Z.; Nie, X.; Li, X.; Qian, P.; Qin, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. CRISPR Screening of Porcine sgRNA Library Identifies Host Factors Associated with Japanese Encephalitis Virus Replication. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.M.; Zhang, W.; Werid, G.M.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Isolation, Characterization, and Molecular Detection of Porcine Sapelovirus. Viruses 2022, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackova, A.; Sliz, I.; Mandelik, R.; Salamunova, S.; Novotny, J.; Kolesarova, M.; Vlasakova, M.; Vilcek, S. Porcine Kobuvirus 1 in Healthy and Diarrheic Pigs: Genetic Detection and Characterization of Virus and Co-Infection with Rotavirus A. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 49, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpić, J.; Keros, T.; Božiković, M.; Kamber, M.; Jemeršić, L. Current Insights into Porcine Bocavirus (PBoV) and Its Impact on the Economy and Public Health. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, M.; Pluym, L.; Maes, D.; Olstad, K.; Zoric, M. Lameness in Pigs. In Production Diseases in Farm Animals: Pathophysiology, Prophylaxis and Health Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 405–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.-H.; Yin, L.-L.; Tang, Z.-S.; Xiang, T.; Ma, G.-J.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Zhao, S.-H.; Liu, X.-D. Identification of Novel Variants and Candidate Genes Associated with Porcine Bone Mineral Density Using Genome-Wide Association Study. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, M.L.; Calabrese, G.M.; Mesner, L.D.; Godfrey, D.A.; Maynard, R.D.; Ackert-Bicknell, C.L.; Farber, C.R. Genetic Analysis of Osteoblast Activity Identifies Zbtb40 as a Regulator of Osteoblast Activity and Bone Mass. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenoi, W.; Rangkasenee, N.; Uddin, M.J.; Cinar, M.U.; Phatsara, C.; Tesfaye, D.; Scholz, A.M.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; Mielenz, M.; et al. Association and Expression Study of MMP3, TGFβ1 and COL10A1 as Candidate Genes for Leg Weakness-Related Traits in Pigs. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 3893–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Qiao, C.-M.; Liu, W.-W.; Jiang, H.-Y.; Jing, Q.-Q.; Liao, Y.-Y.; Ren, J.; Xing, Y.-Y. BMPR-IB gene disruption causes severe limb deformities in pigs. Zool. Res. 2022, 43, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangkasenee, N.; Murani, E.; Brunner, R.; Schellander, K.; Cinar, M.U.; Scholz, A.M.; Luther, H.; Hofer, A.; Ponsuksili, S.; Wimmers, K. KRT8, FAF1 and PTH1R Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Leg Weakness Traits in Pigs. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matika, O.; Robledo, D.; Pong-Wong, R.; Bishop, S.C.; Riggio, V.; Finlayson, H.; Lowe, N.R.; Hoste, A.E.; Walling, G.A.; del-Pozo, J.; et al. Balancing Selection at a Premature Stop Mutation in the Myostatin Gene Underlies a Recessive Leg Weakness Syndrome in Pigs. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantseva, A.; Bilyalov, A.; Filatov, N.; Perepechenov, S.; Gusev, O. Genetic Contributions to Aggressive Behaviour in Pigs: A Comprehensive Review. Genes 2025, 16, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, E.J.; Bone, C.; Cameron, J. Pork Production with Entire Males: Directions for Control of Boar Taint. Animals 2020, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunshea, F.R.; Allison, J.R.D.; Bertram, M.; Boler, D.D.; Brossard, L.; Campbell, R.; Crane, J.P.; Hennessy, D.P.; Huber, L.; De Lange, C.; et al. The Effect of Immunization against GnRF on Nutrient Requirements of Male Pigs: A Review. Animal 2013, 7, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, J.M.; Parrilla, I.; Roca, J.; Gil, M.A.; Cuello, C.; Vazquez, J.L.; Martínez, E.A. Sex-Sorting Sperm by Flow Cytometry in Pigs: Issues and Perspectives. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijvesteijn, N.; Knol, E.F.; Merks, J.W.; Crooijmans, R.P.; Groenen, M.A.; Bovenhuis, H.; Harlizius, B. A Genome-Wide Association Study on Androstenone Levels in Pigs Reveals a Cluster of Candidate Genes on Chromosome 6. BMC Genet. 2010, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bourneuf, E.; Marklund, S.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Madej, A.; Lundström, K. Gene Expression of 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase and 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase in Relation to Androstenone, Testosterone, and Estrone Sulphate in Gonadally Intact Male and Castrated Pigs1. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 2457–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Suzuki, I.; Tasaka, Y.; Kano, K.; Taguchi, Y.; Mikami, K.; Hirabayashi, M.; Kashiwazaki, N.; et al. Functional Expression of a Δ12 Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene from Spinach in Transgenic Pigs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6361–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Kang, J.X.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Witt, W.T.; Yong, H.Y.; Hao, Y.; Wax, D.M.; Murphy, C.N.; Rieke, A.; et al. Generation of Cloned Transgenic Pigs Rich in Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 435–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovan, S.P.; Meidinger, R.G.; Ajakaiye, A.; Cottrill, M.; Wiederkehr, M.Z.; Barney, D.J.; Plante, C.; Pollard, J.W.; Fan, M.Z.; Hayes, M.A.; et al. Pigs Expressing Salivary Phytase Produce Low-Phosphorus Manure. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 741–745, Correction in Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, D.; Cai, G.; Li, G.; Mo, J.; Wang, D.; Zhong, C.; Wang, H.; et al. Novel Transgenic Pigs with Enhanced Growth and Reduced Environmental Impact. eLife 2018, 7, e34286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meidinger, R.G.; Ajakaiye, A.; Fan, M.Z.; Zhang, J.; Phillips, J.P.; Forsberg, C.W. Digestive Utilization of Phosphorus from Plant-Based Diets in the Cassie Line of Transgenic Yorkshire Pigs That Secrete Phytase in the Saliva1. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.S.; Yang, C.C.; Hsu, C.C.; Hsu, J.T.; Wu, S.C.; Lin, C.J.; Cheng, W.T.K. Establishment of a Novel, Eco-Friendly Transgenic Pig Model Using Porcine Pancreatic Amylase Promoter-Driven Fungal Cellulase Transgenes. Transgenic Res. 2015, 24, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Cai, J.; Zhao, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shu, G.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Xi, Q.; et al. Improvement of Anti-Nutritional Effect Resulting from β-Glucanase Specific Expression in the Parotid Gland of Transgenic Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 597841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Zhong, C.; Mo, J.; Sun, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhou, R.; Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; et al. Generation of Multi-Transgenic Pigs Using PiggyBac Transposons Co-Expressing Pectinase, Xylanase, Cellulase, β-1.3-1.4-Glucanase and Phytase. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 597841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, M.S.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.; Cook, J.B.; Bleck, G.T.; Hurley, W.L.; Wheeler, M.B. Lactational Performance of First-Parity Transgenic Gilts Expressing Bovine Alpha-Lactalbumin in Their Milk. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, N. Expression of Recombinant Human α-Lactalbumin in Milk of Transgenic Cloned Pigs Is Sufficient to Enhance Intestinal Growth and Weight Gain of Suckling Piglets. Gene 2016, 584, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, S.; Shang, S.; Wu, F.; Wen, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Production of Transgenic-Cloned Pigs Expressing Large Quantities of Recombinant Human Lysozyme in Milk. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, A.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X.; Cui, C.; Piao, Y.; Guan, L. The Aflatoxin-Detoxifizyme Specific Expression in the Parotid Gland of Transgenic Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsoondar, J.; Vaught, T.; Ball, S.; Mendicino, M.; Monahan, J.; Jobst, P.; Vance, A.; Duncan, J.; Wells, K.; Ayares, D. Production of Transgenic Pigs That Express Porcine Endogenous Retrovirus Small Interfering RNAs. Xenotransplantation 2009, 16, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Zheng, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Feng, W.; et al. shRNA Transgenic Swine Display Resistance to Infection with the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, Q.; Bao, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, K.; Li, N. RNAi-Based Inhibition of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Replication in Transgenic Pigs. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 171, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Zhang, J.; Bai, L.; Mu, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Sheng, A.; Li, K. The Transgenic Cloned Pig Population with Integrated and Controllable GH Expression That Has Higher Feed Efficiency and Meat Production. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Tu, C.-F.; Huang, S.-Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Tzang, B.-S.; Hseu, T.-H.; Lee, W.-C. Augmentation of Thermotolerance in Primary Skin Fibroblasts from a Transgenic Pig Overexpressing the Porcine HSP70.2. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, C.; Macedo, M.; Buha, T.; De Donato, M.; Costas, B.; Mancera, J.M. Genetically Modified Animal-Derived Products: From Regulations to Applications. Animals 2025, 15, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Vaught, T.D.; Boone, J.; Chen, S.-H.; Phelps, C.J.; Ball, S.; Monahan, J.A.; Jobst, P.M.; McCreath, K.J.; Lamborn, A.E.; et al. Targeted Disruption of the A1,3-Galactosyltransferase Gene in Cloned Pigs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, J. Who Killed the EnviroPig? Assemblages, Genetically Engineered Animals and Patents. Griffith Law Rev. 2015, 24, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eenennaam, A.L.; De Figueiredo Silva, F.; Trott, J.F.; Zilberman, D. Genetic Engineering of Livestock: The Opportunity Cost of Regulatory Delay. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, H.; No, J.; Lee, S.; Oh, K. Gene Editing for Enhanced Swine Production: Current Advances and Prospects. Animals 2025, 15, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.; Prather, R.S.; Lee, K. Use of Gene-Editing Technology to Introduce Targeted Modifications in Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber Sichani, A.; Ranjbar, M.; Baneshi, M.; Torabi Zadeh, F.; Fallahi, J. A Review on Advanced CRISPR-Based Genome-Editing Tools: Base Editing and Prime Editing. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; He, Y.; Zhu, X.; Peng, W.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liao, G.; Ni, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. One-Step in vivo Gene Knock-out in Porcine Embryos Using Recombinant Adeno-Associated Viruses. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1376936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, N.L.; Forni, M.; Bacci, M.L.; Giovannoni, R.; Razzini, R.; Fantinati, P.; Zannoni, A.; Fusetti, L.; Dalprà, L.; Bianco, M.R.; et al. Multi-Transgenic Pigs Expressing Three Fluorescent Proteins Produced with High Efficiency by Sperm Mediated Gene Transfer. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 72, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavitrano, M.; Bacci, M.L.; Forni, M.; Lazzereschi, D.; Di Stefano, C.; Fioretti, D.; Giancotti, P.; Marfé, G.; Pucci, L.; Renzi, L.; et al. Efficient Production by Sperm-Mediated Gene Transfer of Human Decay Accelerating Factor (hDAF) Transgenic Pigs for Xenotransplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14230–14235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xi, Q.; Ding, J.; Cai, W.; Meng, F.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, Q.; Shu, G.; Wang, S.; et al. Production of transgenic pigs mediated by pseudotyped lentivirus and sperm. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, K.D.; Prather, R.S. Genome-editing Technologies to Improve Research, Reproduction, and Production in Pigs. Mol. Reprod. Devel 2017, 84, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvesen, H.A.; Grupen, C.G.; McFarlane, G.R. Tackling Mosaicism in Gene Edited Livestock. Front. Anim. Sci. 2024, 5, 1368155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzner, W.G.; De Macedo, M.P.; Gutierrez, K.; Bordignon, V. Enhancement of Chromatin and Epigenetic Reprogramming in Porcine SCNT Embryos—Progresses and Perspectives. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 940197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemann, H.; Tian, X.C.; King, W.A.; Lee, R.S.F. Epigenetic Reprogramming in Embryonic and Foetal Development upon Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer Cloning. Reproduction 2008, 135, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preisinger, D.; Winogrodzki, T.; Klinger, B.; Schnieke, A.; Rieblinger, B. Genome editing in pigs. In Transgenesis: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, D.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Du, W.; Zhao, S.; Pang, Y.; Hao, H.; et al. Identification of the Porcine IG-DMR and Abnormal Imprinting of DLK1-DIO3 in Cloned Pigs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 964045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, X.; Cao, L.; Huang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, T.; Jiang, J.; Shi, D. MicroRNA-148a Overexpression Improves the Early Development of Porcine Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer Embryos. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Song, X. Epigenetic Modification Agents Improve Gene-Specific Methylation Reprogramming in Porcine Cloned Embryos. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.J.; Zhu, J.; Xie, B.T.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, S.C.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, Q.R.; He, H.B.; Liu, Z.H. Treating Cloned Embryos, But Not Donor Cells, with 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine Enhances the Developmental Competence of Porcine Cloned Embryos. J. Reprod. Dev. 2013, 59, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, X.; Song, X.; He, H.; Huan, Y. Optimizing 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine Treatment to Enhance the Development of Porcine Cloned Embryos by Inhibiting Apoptosis and Improving DNA Methylation Reprogramming. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Zou, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F.; Ge, W.; Wu, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. XIST Derepression in Active X Chromosome Hinders Pig Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ross, J.W.; Hao, Y.; Spate, L.D.; Walters, E.M.; Samuel, M.S.; Rieke, A.; Murphy, C.N.; Prather, R.S. Significant Improvement in Cloning Efficiency of an Inbred Miniature Pig by Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Treatment after Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer1. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Kwon, H.-S.; Kwon, D.; Koo, O.-J.; Moon, J.-H.; Park, E.-J.; Yum, S.-Y.; Lee, B.-C.; Jang, G. Production of Transgenic Porcine Embryos Reconstructed with Induced Pluripotent Stem-Like Cells Derived from Porcine Endogenous Factors Using PiggyBac System. Cell. Reprogram. 2019, 21, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, R.; Shen, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, N.; Yang, F.; Wei, H.; et al. ESRRB Facilitates the Conversion of Trophoblast-Like Stem Cells From Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells by Directly Regulating CDX2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 712224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Gao, D.; Zhong, L.; Zhi, M.; Weng, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Du, X.; Xin, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. IRF-1 expressed in the inner cell mass of the porcine early blastocyst enhances the pluripotency of induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neira, J.A.; Conrad, J.V.; Rusteika, M.; Chu, L.-F. The Progress of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived from Pigs: A Mini Review of Recent Advances. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1371240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, J.V.; Meyer, S.; Ramesh, P.S.; Neira, J.A.; Rusteika, M.; Mamott, D.; Duffin, B.; Bautista, M.; Zhang, J.; Hiles, E.; et al. Efficient derivation of transgene-free porcine induced pluripotent stem cells enables in vitro modeling of species-specific developmental timing. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 2328–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezashi, T.; Telugu, B.P.V.L.; Alexenko, A.P.; Sachdev, S.; Sinha, S.; Roberts, R.M. Derivation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from Pig Somatic Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10993–10998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ruan, D.; Liu, P. Reprogramming porcine fibroblast to EPSCs. In Nuclear Reprogramming: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Nowak-Imialek, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Herrmann, D.; Ruan, D.; Chen, A.C.H.; Eckersley-Maslin, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, Y.L.; et al. Establishment of Porcine and Human Expanded Potential Stem Cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Oh, D.; Kim, M.; Jawad, A.; Zheng, H.; Cai, L.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.; Lee, G.; Jang, H.; et al. Establishment of Porcine Embryonic Stem Cells in Simplified Serum Free Media and Feeder Free Expansion. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Planells, B.; Klisch, D.; Spindlow, D.; Masaki, H.; Bornelöv, S.; Stirparo, G.G.; Matsunari, H.; Uchikura, A.; et al. Pluripotent Stem Cells Related to Embryonic Disc Exhibit Common Self-Renewal Requirements in Diverse Livestock Species. Development 2021, 148, dev199901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Q.; Yu, D.; Gao, S.; Gao, D.; Liu, P.; Guo, J.; Hai, T.; Gao, J.; et al. Generation and characterization of stable pig pregastrulation epiblast stem cell lines. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-H.; Lee, D.-K.; Kim, S.W.; Woo, S.-H.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, C.-K. Chemically Defined Media Can Maintain Pig Pluripotency Network In Vitro. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 13, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, R.A.; Kühholzer, B.; Chan, A.W.S.; Lai, L.; Park, K.-W.; Chong, K.-Y.; Schatten, G.; Murphy, C.N.; Abeydeera, L.R.; Day, B.N.; et al. Transgenic pigs produced using in vitro matured oocytes infected with a retroviral vector. Anim. Biotechnol. 2001, 12, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, A.; Kessler, B.; Ewerling, S.; Weppert, M.; Vogg, B.; Ludwig, H.; Stojkovic, M.; Boelhauve, M.; Brem, G.; Wolf, E.; et al. Efficient Transgenesis in Farm Animals by Lentiviral Vectors. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitelaw, C.B.A.; Radcliffe, P.A.; Ritchie, W.A.; Carlisle, A.; Ellard, F.M.; Pena, R.N.; Rowe, J.; Clark, A.J.; King, T.J.; Mitrophanous, K.A. Efficient Generation of Transgenic Pigs Using Equine Infectious Anaemia Virus (EIAV) Derived Vector. FEBS Lett. 2004, 571, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakritbudsabong, W.; Sariya, L.; Jantahiran, P.; Chaisilp, N.; Chaiwattanarungruengpaisan, S.; Rungsiwiwut, R.; Ferreira, J.N.; Rungarunlert, S. Generation of Porcine Induced Neural Stem Cells Using the Sendai Virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 806785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Á.; Reina, R. Recombinant Sendai Virus Vectors as Novel Vaccine Candidates Against Animal Viruses. Viruses 2025, 17, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashita, Y.; Ohtsuru, A.; Fujioka, H.; Kamohara, Y.; Kawazoe, Y.; Sugiyama, N.; Eguchi, S.; Kuroda, H.; Furui, J.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Safe and Efficient Gene Transfer into Porcine Hepatocytes Using Sendai Virus-Cationic Liposomes for Bioartificial Liver Support. Artif. Organs 2000, 24, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, R.D.; Lillegard, J.B.; Fisher, J.E.; McKenzie, T.J.; Hofherr, S.E.; Finegold, M.J.; Nyberg, S.L.; Grompe, M. Efficient Production of Fah -Null Heterozygote Pigs by Chimeric Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Knockout and Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmailov, A.; Minyazeva, I.; Markosyan, V.; Safiullov, Z.; Gazizov, I.; Salafutdinov, I.; Markelova, M.; Garifulin, R.; Shmarov, M.; Logunov, D.; et al. Biosafety Evaluation of a Chimeric Adenoviral Vector in Mini-Pigs: Insights into Immune Tolerance and Gene Therapy Potential. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, G.; Huang, Y. Applications of PiggyBac Transposons for Genome Manipulation in Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 3829286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.J.; Carlson, D.F.; Fahrenkrug, S.C. Pigs Taking Wing with Transposons and Recombinases. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zou, X.; Zeng, F.; Shi, J.; Liu, D.; Urschitz, J.; Moisyadi, S.; Li, Z. Pig Transgenesis by piggyBac Transposition in Combination with Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Transgenic Res. 2013, 22, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zeng, F.; Meng, F.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Tang, F.; Gao, W.; Shi, J.; He, X.; et al. Generation of Transgenic Pigs by Cytoplasmic Injection of piggyBac Transposase-Based pmGENIE-3 Plasmids1. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 90, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Cecil, R.; Benne, J.A.; Redel, B.K.; Spate, L.D.; Samuel, M.S.; Prather, R.S.; Wells, K.D. Zygote Injection of RNA Encoding Cre Recombinase Results in Efficient Removal of LoxP Flanked Neomycin Cassettes in Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2018, 27, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauschild, J.; Petersen, B.; Santiago, Y.; Queisser, A.-L.; Carnwath, J.W.; Lucas-Hahn, A.; Zhang, L.; Meng, X.; Gregory, P.D.; Schwinzer, R.; et al. Efficient Generation of a Biallelic Knockout in Pigs Using Zinc-Finger Nucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12013–12017, Correction in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 15010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.J.; Zhao, J.; Wells, K.D.; Samuel, M.S.; Whitworth, K.M.; Walters, E.M.; Laughlin, M.H.; Prather, R.S. Gene Targeting with Zinc Finger Nucleases to Produce Cloned eGFP Knockout Pigs. Mol. Reprod. Devel 2011, 78, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.F.; Tan, W.; Lillico, S.G.; Stverakova, D.; Proudfoot, C.; Christian, M.; Voytas, D.F.; Long, C.R.; Whitelaw, C.B.A.; Fahrenkrug, S.C. Efficient TALEN-Mediated Gene Knockout in Livestock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17382–17387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, T.; Teng, F.; Guo, R.; Li, W.; Zhou, Q. One-Step Generation of Knockout Pigs by Zygote Injection of CRISPR/Cas System. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Lee, K.; Benne, J.A.; Beaton, B.P.; Spate, L.D.; Murphy, S.L.; Samuel, M.S.; Mao, J.; O’Gorman, C.; Walters, E.M.; et al. Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 System to Produce Genetically Engineered Pigs from In Vitro-Derived Oocytes and Embryos1. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Shen, B.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Hu, B.; Kang, N.; et al. Efficient Generation of Gene-Modified Pigs via Injection of Zygote with Cas9/sgRNA. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Benne, J.A.; Spate, L.D.; Murphy, S.L.; Samuel, M.S.; Murphy, C.N.; Richt, J.A.; Walters, E.; Prather, R.S.; Wells, K.D. Zygote Injection of CRISPR/Cas9 RNA Successfully Modifies the Target Gene without Delaying Blastocyst Development or Altering the Sex Ratio in Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Li, H.; Xu, K.; Wu, T.; Wei, J.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Z.; Mu, Y.; Yang, S.; Ouyang, H.; et al. Highly Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Transgene Knockin at the H11 Locus in Pigs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-E.; Powell, A.; Sandmaier, S.E.S.; Kim, C.-M.; Mileham, A.; Donovan, D.M.; Telugu, B.P. Targeted Gene Knock-in by CRISPR/Cas Ribonucleoproteins in Porcine Zygotes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, M.; Wittayarat, M.; Namula, Z.; Le, Q.A.; Lin, Q.; Takebayashi, K.; Thongkittidilok, C.; Mito, T.; Tomonari, S.; Tanihara, F.; et al. Generation of Mutant Pigs by Lipofection-Mediated Genome Editing in Embryos. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Jin, J.; Liu, Z.; Mu, Y. CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein-Mediated Precise Editing of Multiple Genes in Porcine Fibroblasts. Animals 2024, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, K.; Wei, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, S. Generation of Porcine Fetal Fibroblasts Expressing the Tetracycline-Inducible Cas9 Gene by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 2527–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Tu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Cas9-Mediated Replacement of Expanded CAG Repeats in a Pig Model of Huntington’s Disease. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRISPR Livestock and Poultry Knockout Libraries. Available online: https://cellecta.com/products/crispr-livestock-and-poultry-knockout-libraries (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Li, Z.; Duan, X.; An, X.; Feng, T.; Li, P.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, P.; Pan, D.; Du, X.; et al. Efficient RNA-Guided Base Editing for Disease Modeling in Pigs. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ge, W.; Li, N.; Liu, Q.; Chen, F.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Efficient Base Editing for Multiple Genes and Loci in Pigs Using Base Editors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yu, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, M.; Tang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Efficient Base Editing by RNA-Guided Cytidine Base Editors (CBEs) in Pigs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, S.; Zong, R.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J. An Optimized Prime Editing System for Efficient Modification of the Pig Genome. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2851–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Duan, W.; Peng, Z.; Liao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Jing, Q.; Jiang, H.; Fan, Y.; Ge, L.; et al. Highly Efficient Prime Editors for Mammalian Genome Editing Based on Porcine Retrovirus Reverse Transcriptase. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 3253–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.S.; Kim, S.; Choi, A.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, H.; No, J.; Lee, S.; Oh, K.; Yoo, J.G. AAV2 Serotype Demonstrates the Highest Transduction Efficiency in Porcine Lung-Derived Cells. J. Anim. Reprod. Biotechnol. 2015, 39, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-E.; Kaucher, A.V.; Powell, A.; Waqas, M.S.; Sandmaier, S.E.S.; Oatley, M.J.; Park, C.-H.; Tibary, A.; Donovan, D.M.; Blomberg, L.A.; et al. Generation of Germline Ablated Male Pigs by CRISPR/Cas9 Editing of the NANOS2 Gene. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Says GM Pigs Safe to Eat. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, R.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Cai, G.; Wu, Z. CD163 Knockout Pigs Are Fully Resistant to Highly Pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Antivir. Res. 2018, 151, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkard, C.; Lillico, S.G.; Reid, E.; Jackson, B.; Mileham, A.J.; Ait-Ali, T.; Whitelaw, C.B.A.; Archibald, A.L. Precision Engineering for PRRSV Resistance in Pigs: Macrophages from Genome Edited Pigs Lacking CD163 SRCR5 Domain Are Fully Resistant to Both PRRSV Genotypes While Maintaining Biological Function. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkard, C.; Opriessnig, T.; Mileham, A.J.; Stadejek, T.; Ait-Ali, T.; Lillico, S.G.; Whitelaw, C.B.A.; Archibald, A.L. Pigs Lacking the Scavenger Receptor Cysteine-Rich Domain 5 of CD163 Are Resistant to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus 1 Infection. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00415-18, Erratum in J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00951-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, K.M.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Petrovan, V.; Sheahan, M.; Cino-Ozuna, A.G.; Fang, Y.; Hesse, R.; Mileham, A.; Samuel, M.S.; Wells, K.D.; et al. Resistance to Coronavirus Infection in Amino Peptidase N-Deficient Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2019, 28, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, A.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Petrovan, V.; Sheahan, M.; Samuel, M.S.; Whitworth, K.M.; Wells, K.D.; Zhang, J.; Beaton, B.; Cigan, M.; et al. The Use of Cells from ANPEP Knockout Pigs to Evaluate the Role of Aminopeptidase N (APN) as a Receptor for Porcine Deltacoronavirus (PDCoV). Virology 2020, 541, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Mu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hou, S.; Xiong, Y.; Fang, L.; Ge, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. CD163 and pAPN Double-Knockout Pigs Are Resistant to PRRSV and TGEV and Exhibit Decreased Susceptibility to PDCoV While Maintaining Normal Production Performance. eLife 2020, 9, e57132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.-F.; Chuang, C.; Hsiao, K.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, C.-M.; Peng, S.-H.; Su, Y.-H.; Chiou, M.-T.; Yen, C.-H.; Hung, S.-W.; et al. Lessening of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea Virus Susceptibility in Piglets after Editing of the CMP-N-Glycolylneuraminic Acid Hydroxylase Gene with CRISPR/Cas9 to Nullify N-Glycolylneuraminic Acid Expression. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooke, H.; Schwindt, S.; Fletcher, S.L.; Isken, O.; Harding, S.; Berkley, N.; Tait-Burkard, C.; Warren, C.; Whitelaw, C.B.A.; Tautz, N.; et al. DNAJC14 Gene-Edited Pigs Are Resistant to Classical Pestiviruses. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, in press. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, C.; Fu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Genome-Scale CRISPR Screen Identifies TMEM41B as a Multi-Function Host Factor Required for Coronavirus Replication. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jin, Q.; Xiao, W.; Fang, P.; Lai, L.; Xiao, S.; Wang, K.; Fang, L. Genome-Wide CRISPR/Cas9 Screen Reveals a Role for SLC35A1 in the Adsorption of Porcine Deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e01626-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, C.; Ghonaim, A.H.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, P.; Guo, G.; Evers, A.; Zhu, H.; et al. Genome-Wide CRISPR/Cas9 Library Screen Identifies C16orf62 as a Host Dependency Factor for Porcine Deltacoronavirus Infection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2400559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Reveals Host Factors for Gama- and Delta-Coronavirus Infection in Huh7 Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xi, X.; Xiang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Su, Y.; He, R.; Xiong, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Cytosine Base Editing Screen for the Functional Assessment of CALR Intron Variants in Japanese Encephalitis Virus Replication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Zhang, G.; Weng, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. A genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screen identifies TMEM239 as an important host factor in facilitating African swine fever virus entry into early endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillico, S.G.; Proudfoot, C.; King, T.J.; Tan, W.; Zhang, L.; Mardjuki, R.; Paschon, D.E.; Rebar, E.J.; Urnov, F.D.; Mileham, A.J.; et al. Mammalian Interspecies Substitution of Immune Modulatory Alleles by Genome Editing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, S.; Strong, R.; McCarthy, R.R.; Edwards, J.C.; Howes, E.L.; Stevens, L.M.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Núñez, A.; Watson, S.; Mileham, A.J.; et al. Substitution of Warthog NF-κB Motifs into RELA of Domestic Pigs Is Not Sufficient to Confer Resilience to African Swine Fever Virus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Petersen, B.; Keil, G.M.; Niemann, H.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Fuchs, W. Efficient Inhibition of African Swine Fever Virus Replication by CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting of the Viral P30 Gene (CP204L). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Xu, L.; Gao, Y.; Dou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, X.; He, X.; Tian, Z.; Song, L.; Mo, G.; et al. Testing Multiplexed Anti-ASFV CRISPR-Cas9 in Reducing African Swine Fever Virus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02164-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zou, J.; Tu, S.; Luo, D.; Xiao, R.; Du, Y.; Xiong, C.; Xie, S.; Liu, H.; Jin, M.; et al. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen Identifies STK11 as a Critical Regulator of Sialic Acid Clusters Important for Influenza A Virus Attachment. J. Adv. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Pang, D.; Wang, K.; Li, M.; Guo, N.; Yuan, H.; Li, J.; Zou, X.; Jiao, H.; Ouyang, H.; et al. Optimization of a CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knock-in Strategy at the Porcine Rosa26 Locus in Porcine Foetal Fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Jiao, H.; Xiao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qi, C.; Zhao, D.; Jiao, S.; Yu, T.; Tang, X.; et al. Generation of pRSAD2 Gene Knock-in Pig via CRISPR/Cas9 Technology. Antivir. Res. 2020, 174, 104696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Pang, D.; Yuan, H.; Jiao, H.; Lu, C.; Wang, K.; Yang, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Yu, T.; et al. Genetically Modified Pigs Are Protected from Classical Swine Fever Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Tang, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Cai, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Jiang, K.; Gao, P.; Ma, D.; et al. Targeted Mutations in Myostatin by Zinc-Finger Nucleases Result in Double-Muscled Phenotype in Meishan Pigs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Fujimura, T.; Matsunari, H.; Sakuma, T.; Nakano, K.; Watanabe, M.; Asano, Y.; Kitagawa, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Nagashima, H. Efficient Modification of the Myostatin Gene in Porcine Somatic Cells and Generation of Knockout Piglets. Mol. Reprod. Devel 2016, 83, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, Z.; Paek, H.; Choe, H.; Yin, X.; Quan, B. Reproduction Traits of Heterozygous Myostatin Knockout Sows Crossbred with Homozygous Myostatin Knockout Boars. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2021, 56, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ouyang, H.; Xie, Z.; Yao, C.; Guo, N.; Li, M.; Jiao, H.; Pang, D. Efficient Generation of Myostatin Mutations in Pigs Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xu, K.; Wu, T.; Ruan, J.; Zheng, X.; Bao, S.; Mu, Y.; Sonstegard, T.; Li, K. Long-Term, Multidomain Analyses to Identify the Breed and Allelic Effects in MSTN-Edited Pigs to Overcome Lameness and Sustainably Improve Nutritional Meat Production. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Li, Z.; Zou, Y.; Hao, H.; Li, N.; Li, Q. An FBXO40 Knockout Generated by CRISPR/Cas9 Causes Muscle Hypertrophy in Pigs without Detectable Pathological Effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 498, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Li, R.; Zeng, J.; Mo, D.; Cong, P.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; He, Z. Disruption of the ZBED6 Binding Site in Intron 3 of IGF2 by CRISPR/Cas9 Leads to Enhanced Muscle Development in Liang Guang Small Spotted Pigs. Transgenic Res. 2019, 28, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.; Li, M.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Ouyang, H.; Pang, D. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Specific Integration of Fat-1 and IGF-1 at the pRosa26 Locus. Genes 2021, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yin, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, R.; Li, Q.; Pan, J.; Zhang, J. CRISPR/Cas9-Meditated Gene Knockout in Pigs Proves That LGALS12 Deficiency Suppresses the Proliferation and Differentiation of Porcine Adipocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2024, 1869, 159424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, A.N.; Lucas, C.G.; Safranski, T.J.; Prather, R.S.; Wells, K.D.; Restrepo, D.C.; Lucy, M.C. 83 Body Weight from Birth to 260 Days of Age for Pigs with Functional Deletions in Growth Hormone Receptor (GHR) Promoters Created Using CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Hambly, C.; Qin, G.; Yao, J.; et al. Reconstitution of UCP1 Using CRISPR/Cas9 in the White Adipose Tissue of Pigs Decreases Fat Deposition and Improves Thermogenic Capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9474–E9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Mo, J.; Zhong, C.; Shi, J.; Zhou, R.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Wu, Z.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Integration of Large Transgene into Pig CEP112 Locus. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2020, 10, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Bu, G.; Hou, L.; et al. Targeted Overexpression of PPARγ in Skeletal Muscle by Random Insertion and CRISPR/Cas9 Transgenic Pig Cloning Enhances Oxidative Fiber Formation and Intramuscular Fat Deposition. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, A.; Huang, C.; Sun, Y.; Song, B.; Zhou, R.; Li, L. Generation of Marker-Free Pbd-2 Knock-in Pigs Using the CRISPR/Cas9 and Cre/loxP Systems. Genes 2020, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Onteru, S.K.; Nikkilä, M.T.; Stalder, K.J.; Rothschild, M.F. Identification of Genetic Markers Associated with Fatness and Leg Weakness Traits in the Pig. Anim. Genet. 2009, 40, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenoi, W.; Uddin, M.J.; Cinar, M.U.; Phatsara, C.; Tesfaye, D.; Scholz, A.M.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; Mielenz, M.; Sauerwein, H.; et al. Molecular Characterization and Methylation Study of Matrix Gla Protein in Articular Cartilage from Pig with Osteochondrosis. Gene 2010, 459, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.M.; Ai, H.S.; Ren, J.; Wang, G.J.; Wen, Y.; Mao, H.R.; Lan, L.T.; Ma, J.W.; Brenig, B.; Rothschild, M.F.; et al. A Whole Genome Scan for Quantitative Trait Loci for Leg Weakness and Its Related Traits in a Large F2 Intercross Population between White Duroc and Erhualian1. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laenoi, W.; Uddin, M.J.; Cinar, M.U.; Große-Brinkhaus, C.; Tesfaye, D.; Jonas, E.; Scholz, A.M.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; Wimmers, K.; et al. Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis for Leg Weakness-Related Traits in a Duroc × Pietrain Crossbred Population. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2011, 43, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemoto, Y.; Sato, S.; Ohnishi, C.; Hirose, K.; Kameyama, K.; Fukawa, K.; Kudo, O.; Kobayashi, E. Quantitative Trait Loci for Leg Weakness Traits in a Landrace Purebred Population. Anim. Sci. J. 2010, 81, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriver, A.; McConnachie, E. Genetically Modifying Livestock for Improved Welfare: A Path Forward. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2018, 31, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Petersen, B. Pre-Determination of Sex in Pigs by Application of CRISPR/Cas System for Genome Editing. Theriogenology 2019, 137, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, C.; Jayashi, C.; Lightowlers, M.W. Vaccine Development against the Taenia Solium Parasite: The Role of Recombinant Protein Expression in Escherichia coli. Bioengineered 2013, 4, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciutto, E.; Martínez, J.J.; Huerta, M.; Avila, R.; Fragoso, G.; Villalobos, N.; de Aluja, A.; Larralde, C. Familial clustering of Taenia solium cysticercosis in the rural pigs of Mexico: Hints of genetic determinants in innate and acquired resistance to infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 116, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Platform | Typical Delivery Method | Achievable Transformation Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Transfection/microinjection of fibroblasts/zygotes | 84% [145] | Inexpensive and simple. Supports expression of large constructs | Low efficiency, random integration | Transgenesis, transient expression and genome editing |

| Transposon Vector | Transfection/microinjection of a plasmid with target insertion with transposase as separate plasmid, mRNA or protein into cells/zygotes. | 8% [126,127,128,129] | Highly efficient genomic integration. Extremely large cargos (>100 kb for piggyBac). | Random integration, risk of insertional mutagenesis | Efficient transgenesis, especially suitable for insertion of multiple genes (e.g., for xenotransplantation). |

| Recombinase Vector | Transfection of fibroblasts, injection of viral vector into the organ of a genetically engineered pig | 81.9% [130] | Precise excision, inversion, or insertion. Can be delivered to specific tissues in vivo for conditional knockout studies | Requires a pre-existing genetically modified animal with recombination sites. | Targeted integration, tissue-specific or inducible gene activation or inactivation in a live animal. |

| LVV vector | In vitro viral transduction into cells/zygotes by incubation. Local injection. | 70% [19] | Very high delivery efficiency and transgenic yield. Long-term, stable expression, especially in dividing cells. Ideal for stable modification of fibroblasts. Can target non-dividing cells | Complex production in packaging cell lines to supply missing viral proteins. Immune response concerns, poor embryo survival. Integration into the host genome. Limited cargo capacity (~8 kbp) | High-efficiency transgenesis. Generation of stable, Cas-expressing cell lines, which are later edited by sgRNA delivery |

| AAV vector | In vivo injection (Intravenous, in utero, oviductal, into specific organs), in vitro viral transduction by incubation | 64% [150] | Non-integrating. Excellent for in vivo delivery to specific tissues, in vivo embryo editing (oviductal injection) and SMGT. Low immunogenicity. | Complex production in packaging cell lines to supply missing viral proteins. Limited cargo capacity (~4.7 kbp). Expression decreases with cell division | In vivo genome editing and gene therapy. |

| Sendai RNA virus | In vitro viral transduction of fibroblasts by Incubation | 30% [123] | Non-integrating. Non-DNA. High transduction efficiency. | Require specific packaging cells designed to express the fusion protein | Generating iPSCs in pigs by cellular reprogramming without genomic integration of transgenes, vaccine platform for animal diseases |

| Linear DNA (PCR fragments, linearized plasmids) | Co-delivery with CRISPR system (e.g., via microinjection or electroporation). | 6–54% [138] | Simplest form of HDR template. Reduces risk of random plasmid integration. | Very low HDR efficiency, degradation, unstable expression | Serves as a template for homology-directed repair (HDR) for CRISPR-induced knock-in. |

| RNP (Ribonucleoprotein) | Transfection/microinjection of fibroblasts/zygotes | 77% [140] | Rapid action. Highest on-target efficiency, lowest off-target effects. Minimal mosaicism in embryos. Transient (no integration) | Short half-life. Requires co-delivery of a separate template for knock-in. Requires protein production and in vitro RNA synthesis. | Gene knockouts. The gold standard for direct embryo editing. |

| RNA (TALEN or Cas9 mRNA + sgRNA) | 100% [136,137] | longer window of activity, no need for protein synthesis | Requires in vitro RNA synthesis | Gene knockouts. |

| Trait | Porcine Gene | Tagreted by Genome Editing | Confirmed in Live Animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature sensitivity | UCP1 | yes | yes |

| Temperature sensitivity | HSP70 | no | no |

| Allergic reactions | GGTA1 | yes | yes |

| Male sterility | NANOS2 | yes | yes |

| Multiple pregnancy | ESR | no | no |

| Porcine Stress Syndrome | RYR1 | no | no |

| Meat productivity | IGF-2 | yes | yes |

| IGF-1 | yes | yes | |

| FBXO40 | yes | yes | |

| GHR1A | yes | yes | |

| GHRP2 | yes | yes | |

| Meat productivity, lameness | MSTN | yes | yes |

| Meat quality | LGALS12 | no | no |

| PPARγ | yes | yes | |

| Fat-1 | yes | yes | |

| CAST | no | no | |

| PRKAG3 | no | no | |

| TMCO1 | no | no | |

| LRATD1 | no | no | |

| CKB | no | no | |

| H-FABP | no | no | |

| Anal atresia | GLI2 | no | no |

| Myopathy | SPTBN4 | no | no |

| Congenital splay leg syndrom | FBXO32 | no | no |

| P311 | no | no | |

| HOMER1 | no | no | |

| Antimicrobial qualities | FUT1 | no | no |

| MUC4 | no | no | |

| NRAMP1 | no | no | |

| PBD-2 | yes | yes | |

| PRRSV, TGEV, PEDV, PDCoV, CSFV, PRV resistance | heparan sulfate | no | no |

| CSFV, PRV resistance | RSAD2 | yes | no |

| PRRSV resistance | vimentin | no | no |

| CD151 | no | no | |

| RGS16 | no | no | |

| GBP1 | no | no | |

| GBP5 | no | no | |

| PRRSV and PCV resistance | CD163 | yes | yes |

| CD169 | no | no | |

| CD209 | no | no | |

| TGEV, PEDV, PDCoV resistance | ANPEP | yes | yes |

| integrins αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ6, and αvβ8 | no | no | |

| SPPL3 | yes | no | |

| TGEV resistance | TMEM41B | yes | no |

| PDCoV resistance | SLC35A1 | yes | no |

| VPS35L | yes | no | |

| C16orf62 | yes | no | |

| JEV resistance | EMC3 | yes | no |

| CALR | yes | no | |

| PEDV resistance | CMAH | yes | yes |

| CSFV resistance | CD46 | no | no |

| PCBP1 | no | no | |

| BVDV, CSFV resistance | DNAJC14 | yes | yes |

| SVA resistance | ANTXR1 | yes | yes |

| SVA, influenza resistance | TMPRSS2 | yes | yes |

| CSFV and influenza A resistance | Mx1 | no | no |

| Influenza resistance | STK11 | no | no |

| PRV resistance | Nectin 1 and 2 | yes | no |

| ASFV resistance | RELA | yes | yes |

| CD1d | yes | yes | |

| TMEM239 | yes | no | |

| Lameness | CNR2 | no | no |

| Lin28a | no | no | |

| ZBTB40 | no | no | |

| MMP3 | no | no | |

| TGFβ1 | no | no | |

| BMPR-IB | yes | yes | |

| FAF1 | no | no | |

| PTH1R | no | no | |

| KRT8 | no | no | |

| Damaging behaviors | DRD2 | no | no |

| SLC6A4 | no | no | |

| MAOA | no | no | |

| RYR1 | no | no | |

| Boar taint | GnRF | no | no |

| cytochrome P450 | no | no | |

| SULT2A1 and SULT2B1 | no | no | |

| LHB | no | no | |

| 3βHSD | no | no | |

| 17βHSD | no | no |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mikhaylova, E.; Khusnutdinov, E.; Terekhov, M.; Pozdeev, D.; Gusev, O. Pig Genome Editing for Agriculture: Achievements and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412140

Mikhaylova E, Khusnutdinov E, Terekhov M, Pozdeev D, Gusev O. Pig Genome Editing for Agriculture: Achievements and Challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412140

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikhaylova, Elena, Emil Khusnutdinov, Mikhail Terekhov, Daniil Pozdeev, and Oleg Gusev. 2025. "Pig Genome Editing for Agriculture: Achievements and Challenges" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412140

APA StyleMikhaylova, E., Khusnutdinov, E., Terekhov, M., Pozdeev, D., & Gusev, O. (2025). Pig Genome Editing for Agriculture: Achievements and Challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412140