Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Incessant Loop of Immunity to Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

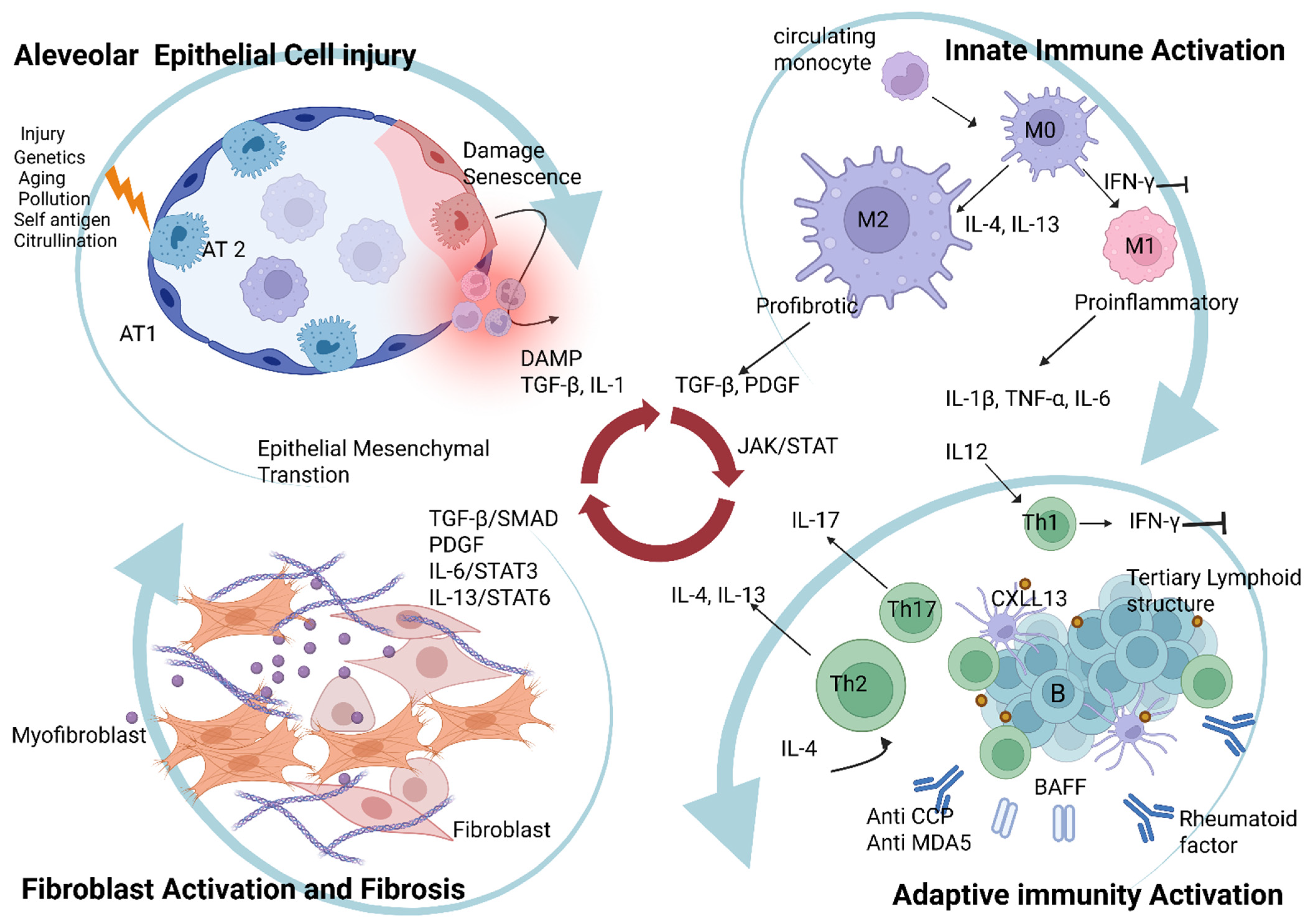

2. Immunopathogenesis of CTD-Associated ILD

2.1. Alveolar Epithelial Cell Injury and Dysfunctional Repair

2.1.1. Mechanisms of Epithelial Injury in CTD-ILD

2.1.2. Dysfunctional Epithelial Repair and Fibrosis

2.1.3. Genetic Predisposition and Senescence

2.2. Innate Immune Responses: Macrophage Polarization as a Bridge to Fibrosis

2.2.1. Macrophage Polarization: M1 vs. M2

2.2.2. Macrophages as a Dynamic Bridge to Fibrosis

2.3. Adaptive Immunity: The Autoimmune Engine of CTD-ILD

2.3.1. T Cells: T Cell Dysregulation and Polarization

T Helper 1 Cells: Antifibrotic Response

T Helper 2 Cells: Profibrotic Drivers

T Helper 17 (Th17) Cells: Sustaining Chronic Inflammation

Regulatory T Cells and Their Complex Roles

Distinct T-Cell Dynamics in IPF vs. CTD-ILD

2.3.2. B Cells: B Cell Activation and Tertiary Lymphoid Structure Formation

Autoantibodies and Their Pathogenic Role

| CTD-ILD Subtype | Predominant ILD Pattern | Key Autoantibodies | Specific Immune/Cellular Features | Distinct Pathogenic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA-ILD [28,124] | UIP | Anti-CCP antibody, Rheumatoid factor | Local protein citrullination, direct alveolar macrophage injury, TLS formation | Immune complex deposition, PAD enzymes, MUC5B-driven dysfunction, smoking-induced fibrotic microenvironment |

| SSc-ILD [30,125] | NSIP | ANAs, Anti-topoisomerase I | Activated fibroblast; Early B cell dysregulation, elevated IL-4/IL-13, TLS formation | Early vascular injury, endothelial dysfunction, alveolar epithelial injury, profibrotic mediators from epithelial cells, TGF- β dominant fibrotic loop |

| Myositis-ILD [126,127] | NSIP | Anti-tRNA synthetase, anti-MDA5, anti-Ro52 antibodies | Hyperinflammatory alveolitis (anti-MDA5), type I IFN induction | tRNA-synthetase antigen recognition in lung, IFN-driven macrophage injury, |

| Sjögren’s-ILD [16] | NSIP | Anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La antibodies | TLS formation, B cell activation | B cell-driven autoimmunity and lymphoid neogenesis |

| Mixed Connective Tissue Disease-ILD [128,129] | NSIP | Anti U1 RNP | Type 1 IFN signature, nucleoprotein immune complex, plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation | U1 RNP immune complex, IFN-I response, endothelial dysfunction/ vasculopathy, fibroblast activation. |

B Cells as Antigen-Presenting and Cytokine-Producing Cells

2.4. Fibroblast Activation and the Progression from Inflammation to Fibrosis

2.4.1. TGF-β: The Master Regulator of Fibrosis

2.4.2. PDGF, FGF and VEGF Signaling

2.4.3. IL-6

2.4.4. IL-13 and IL-17

2.4.5. JAK/STAT Signaling: Integrating Inflammatory and Fibrotic Signals

2.4.6. PDE4: Modulating Immune-Fibrotic Crosstalk

2.4.7. TNF-α and IL-1β

2.4.8. Chemokines and Other Profibrotic Molecules

3. Spectrum of CTD-ILD and IPF

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerro Chiang, G.; Parimon, T. Understanding Interstitial Lung Diseases Associated with Connective Tissue Disease (CTD-ILD): Genetics, Cellular Pathophysiology, and Biologic Drivers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lok, S.S.; Haider, Y.; Howell, D.; Stewart, J.P.; Hasleton, P.S.; Egan, J.J. Murine gammaherpes virus as a cofactor in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in bleomycin resistant mice. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 20, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneaux, P.L.; Willis-Owen, S.A.G.; Cox, M.J.; James, P.; Cowman, S.; Loebinger, M.; Blanchard, A.; Edwards, L.M.; Stock, C.; Daccord, C.; et al. Host-Microbial Interactions in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterbottom, C.J.; Shah, R.J.; Patterson, K.C.; Kreider, M.E.; Panettieri, R.A., Jr.; Rivera-Lebron, B.; Miller, W.T.; Litzky, L.A.; Penning, T.M.; Heinlen, K.; et al. Exposure to Ambient Particulate Matter Is Associated with Accelerated Functional Decline in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2018, 153, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.W.; Liu, H.M.; Xu, F.; Jia, X.H. The role of macrophage polarization and cellular crosstalk in the pulmonary fibrotic microenvironment: A review. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Wei, X.; Ye, T.; Hang, L.; Mou, L.; Su, J. Interrelation Between Fibroblasts and T Cells in Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 747335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, G.; Liu, A.; Herzog, E.L. Evolving Perspectives on Innate Immune Mechanisms of IPF. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 676569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, J.; Salisbury, M.L.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Podolanczuk, A.J.; Hariri, L.P.; Hunninghake, G.M.; Kolb, M.; Ryerson, C.J.; Cottin, V.; Beasley, M.B.; et al. The Role of Inflammation and Fibrosis in Interstitial Lung Disease Treatment Decisions. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Flack, K.F.; Malik, V.; Manichaikul, A.; Sakaue, S.; Luo, Y.; McGroder, C.F.; Salvatore, M.; Anderson, M.R.; Hoffman, E.A.; et al. Genomic and Serological Rheumatoid Arthritis Biomarkers, MUC5B Promoter Variant, and Interstitial Lung Abnormalities. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2024, 22, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Quiroz, K.J.; Rojas-Serrano, J.; Perez-Rubio, G.; Buendia-Roldan, I.; Mejia, M.; Fernandez-Lopez, J.C.; Rodriguez-Henriquez, P.; Ayala-Alcantar, N.; Ramos-Martinez, E.; Lopez-Flores, L.A.; et al. Molecular Factors in PAD2 (PADI2) and PAD4 (PADI4) Are Associated with Interstitial Lung Disease Susceptibility in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Cells 2023, 12, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.S.; Briones, M.R.; Guo, R.; Ostrowski, R.A. Elevated anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody titer is associated with increased risk for interstitial lung disease. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouros, D.; Wells, A.U.; Nicholson, A.G.; Colby, T.V.; Polychronopoulos, V.; Pantelidis, P.; Haslam, P.L.; Vassilakis, D.A.; Black, C.M.; du Bois, R.M. Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Kim, D.S.; Yoo, B.; Seo, J.B.; Rho, J.Y.; Colby, T.V.; Kitaichi, M. Histopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005, 127, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishioka, Y.; Araya, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Kumanogoh, A. Pathological mechanisms and novel drug targets in fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Inflamm. Regen. 2024, 44, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisson, T.H.; Mendez, M.; Choi, K.; Subbotina, N.; Courey, A.; Cunningham, A.; Dave, A.; Engelhardt, J.F.; Liu, X.; White, E.S.; et al. Targeted injury of type II alveolar epithelial cells induces pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 181, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, T.; Shi, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Shu, J.; Alqalyoobi, S.; Zeki, A.A.; Leung, P.S.; Shuai, Z. Interstitial Lung Disease in Connective Tissue Disease: A Common Lesion With Heterogeneous Mechanisms and Treatment Considerations. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 684699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Z.; Nishio, J.; Motomura, K.; Mizutani, S.; Yamada, S.; Mikami, T.; Nanki, T. Senescence of alveolar epithelial cells impacts initiation and chronic phases of murine fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 935114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimon, T.; Chen, P.; Stripp, B.R.; Liang, J.; Jiang, D.; Noble, P.W.; Parks, W.C.; Yao, C. Senescence of alveolar epithelial progenitor cells: A critical driver of lung fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 325, C483–C495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, S.; Cheng, L.; Yu, G. Repair and regeneration of the alveolar epithelium in lung injury. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Du, X.; Cai, Q.; Liu, Z. CD4(+)T and CD8(+)T cells profile in lung inflammation and fibrosis: Targets and potential therapeutic drugs. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1562892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, C.; Yao, C.; Ma, X.; Shen, Z.; Chen, P.; Jiang, Q.; Gong, X. Mucosal immunity and rheumatoid arthritis: An update on mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Autoimmun. Rev. 2025, 24, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sha, S.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Multikingdom characterization of gut microbiota in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, K.; Zaura, E.; Brandt, B.W.; Buijs, M.J.; Brun, J.G.; Crielaard, W.; Bolstad, A.I. Subgingival microbiome of rheumatoid arthritis patients in relation to their disease status and periodontal health. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triggianese, P.; Conigliaro, P.; De Martino, E.; Monosi, B.; Chimenti, M.S. Overview on the Link Between the Complement System and Auto-Immune Articular and Pulmonary Disease. Open Access Rheumatol. 2023, 15, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Quiroz, K.J.; Lopez-Flores, L.A.; Perez-Rubio, G.; Rojas-Serrano, J.; Falfan-Valencia, R. Peptidyl Arginine Deiminases in Chronic Diseases: A Focus on Rheumatoid Arthritis and Interstitial Lung Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, K.D.; Trachalaki, A.; Tsitoura, E.; Koutsopoulos, A.V.; Lagoudaki, E.D.; Lasithiotaki, I.; Margaritopoulos, G.; Pantelidis, P.; Bibaki, E.; Siafakas, N.M.; et al. Upregulation of citrullination pathway: From Autoimmune to Idiopathic Lung Fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palterer, B.; Vitiello, G.; Del Carria, M.; D’Onofrio, B.; Martinez-Prat, L.; Mahler, M.; Cammelli, D.; Parronchi, P. Anti-protein arginine deiminase antibodies are distinctly associated with joint and lung involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 2410–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Song, Y.; Li, M. Biological mechanisms of pulmonary inflammation and its association with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1530753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronzer, V.L.; Hayashi, K.; Yoshida, K.; Davis, J.M., 3rd; McDermott, G.C.; Huang, W.; Dellaripa, P.F.; Cui, J.; Feathers, V.; Gill, R.R.; et al. Autoantibodies against citrullinated and native proteins and prediction of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: A nested case-control study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e77–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, C.; Tervaert, J.W. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, R.A.; Fisher, A.J.; Borthwick, L.A. The Role of Epithelial Damage in the Pulmonary Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzen, J.; Beers, M.F. Contributions of alveolar epithelial cell quality control to pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5088–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Wang, W.; Qin, W.; Cheng, K.; Coulup, S.; Chavez, S.; Jiang, S.; Raparia, K.; De Almeida, L.M.V.; Stehlik, C.; et al. TLR4-dependent fibroblast activation drives persistent organ fibrosis in skin and lung. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, W.S.; Newton, C.A.; Linderholm, A.L.; Neely, M.L.; Pugashetti, J.V.; Kaul, B.; Vo, V.; Echt, G.A.; Leon, W.; Shah, R.J.; et al. Proteomic biomarkers of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: A multicentre cohort analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Hong, S.; Han, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, G. HMGB1 induces lung fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation through NF-kappaB-mediated TGF-beta1 release. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 3062–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Wu, Z.; Mi, L.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Peng, X.; Xu, K.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L. Anti-citrullinated Protein Antibody Generation, Pathogenesis, Clinical Application, and Prospects. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 802934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wei, W.; Chang, Y. The Role and Research Progress of ACPA in the Diagnosis and Pathological Mechanism of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Hum. Immunol. 2025, 86, 111219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, L.; Rosas, I.O.; Gochuico, B.R.; Mikuls, T.R.; Dellaripa, P.F.; Oddis, C.V.; Ascherman, D.P. Identification of citrullinated hsp90 isoforms as novel autoantigens in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y. Alveolar epithelial cell dysfunction and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1564176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzis, E.; Wasson, C.W.; Del Galdo, F. Alveolar epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in scleroderma interstitial lung disease: Technical challenges, available evidence and therapeutic perspectives. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2024, 9, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Fu, X.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Dong, P. M2 macrophages induce EMT through the TGF-beta/Smad2 signaling pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 2017, 41, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, P.J.; Ebner, R.; Lopez, A.R.; Derynck, R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: Involvement of type I receptors. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 127, 2021–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, L.M.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, C. Snail represses the splicing regulator epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 36435–36442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Sun, Q.; Davis, F.; Mao, J.; Zhao, H.; Ma, D. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in organ fibrosis development: Current understanding and treatment strategies. Burns Trauma 2022, 10, tkac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salton, F.; Volpe, M.C.; Confalonieri, M. Epithelial(-)Mesenchymal Transition in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina 2019, 55, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.D.; Lee, J.S.; Kozlitina, J.; Noth, I.; Devine, M.S.; Glazer, C.S.; Torres, F.; Kaza, V.; Girod, C.E.; Jones, K.D.; et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M.; Lee, S.; Neely, J.; Hinchcliff, M.; Wolters, P.J.; Sirota, M. Gene expression meta-analysis reveals aging and cellular senescence signatures in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1326922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, P.A.; Borie, R.; Kannengiesser, C.; Gazal, S.; Revy, P.; Wemeau-Stervinou, L.; Debray, M.P.; Ottaviani, S.; Marchand-Adam, S.; Nathan, N.; et al. Shared genetic predisposition in rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease and familial pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1602314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanios, M.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Cogan, J.D.; Alder, J.K.; Ingersoll, R.G.; Markin, C.; Lawson, W.E.; Xie, M.; Vulto, I.; Phillips, J.A., 3rd; et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomaki, A.; FinnGen Rheumatology Clinical Expert Group; Palotie, A.; Koskela, J.; Eklund, K.K.; Pirinen, M.; Ripatti, S.; Laitinen, T.; Mars, N. Lifetime risk of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease in MUC5B mutation carriers. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1530–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, M.A.; Wise, A.L.; Speer, M.C.; Steele, M.P.; Brown, K.K.; Loyd, J.E.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Zhang, W.; Gudmundsson, G.; Groshong, S.D.; et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, P.A.; Lee, J.S.; Ebstein, E.; Furukawa, H.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Gazal, S.; Kannengiesser, C.; Ottaviani, S.; Oka, S.; Tohma, S.; et al. MUC5B Promoter Variant and Rheumatoid Arthritis with Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Baez, C.; Rangel-Pelaez, C.; Rodriguez-Martin, I.; Kerick, M.; Guillen-Del-Castillo, A.; Simeon-Aznar, C.P.; Callejas, J.L.; Voskuyl, A.E.; Kreuter, A.; Distler, O.; et al. Assessing the MUC5B promoter variant in a large cohort of systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manali, E.D.; Kannengiesser, C.; Borie, R.; Ba, I.; Bouros, D.; Markopoulou, A.; Antoniou, K.; Kolilekas, L.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Tzilas, V.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Relationships in Inheritable Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Greek National Cohort Study. Respiration 2022, 101, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.T.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.S.; Kim, J.N.; Park, W.H.; Yoo, I.S.; Yoo, S.J.; et al. Association of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of PADI4 and HLA-DRB1 Alleles with Susceptibility to Rheumatoid Arthritis-Related Lung Diseases. Lung 2016, 194, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardinello, N.; Zen, M.; Castelli, G.; Cocconcelli, E.; Balestro, E.; Borie, R.; Spagnolo, P. Navigating interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA-ILD): From genetics to clinical landscape. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1542400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.M.; Baker, J.F.; Poole, J.A.; Ascherman, D.P.; Yang, Y.; Kerr, G.S.; Reimold, A.; Kunkel, G.; Cannon, G.W.; Wysham, K.D.; et al. Genetic, social, and environmental risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 57, 152098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noth, I.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.F.; Flores, C.; Barber, M.; Huang, Y.; Broderick, S.M.; Wade, M.S.; Hysi, P.; Scuirba, J.; et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, M.; Butt, A.; Borie, R.; Debray, M.P.; Bouvry, D.; Filhol-Blin, E.; Desroziers, T.; Nau, V.; Copin, B.; Dastot-Le Moal, F.; et al. Functional assessment and phenotypic heterogeneity of SFTPA1 and SFTPA2 mutations in interstitial lung diseases and lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetselaar, R.; van Batenburg, A.A.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; Kazemier, K.M.; Roothaan, S.M.; Peeters, T.; van der Vis, J.J.; Goldschmeding, R.; Grutters, J.C.; van Moorsel, C.H.M. Short telomere length in IPF lung associates with fibrotic lesions and predicts survival. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Ma, S.F.; Garcia, J.G.; Richards, T.J.; Silveira, L.J.; Lindell, K.O.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.E.; et al. Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA 2013, 309, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.V.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Evans, C.M.; Schwarz, M.I.; Schwartz, D.A. MUC5B and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, S193–S199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, R.; Kheir, F. Genomic classifier: Biomarker for progression in interstitial lung disease. ERJ Open Res. 2025, 11, 01013-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lederer, D.J.; Lynch, D.A.; Colby, T.V.; Myers, J.L.; Groshong, S.D.; Larsen, B.T.; Chung, J.H.; Steele, M.P.; et al. Use of a molecular classifier to identify usual interstitial pneumonia in conventional transbronchial lung biopsy samples: A prospective validation study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Jiang, D.Y.; Huang, X.X.; Guo, S.L.; Yuan, W.; Dai, H.P. Toll-like receptor 4 promotes fibrosis in bleomycin-induced lung injury in mice. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 17391–17398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Liang, J.; Fan, J.; Yu, S.; Chen, S.; Luo, Y.; Prestwich, G.D.; Mascarenhas, M.M.; Garg, H.G.; Quinn, D.A.; et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrat, F.J.; Meeker, T.; Gregorio, J.; Chan, J.H.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; Chang, B.; Duramad, O.; Coffman, R.L. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for Toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibl, R.; Birchler, T.; Loeliger, S.; Hossle, J.P.; Gay, R.E.; Saurenmann, T.; Michel, B.A.; Seger, R.A.; Gay, S.; Lauener, R.P. Expression and regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 162, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Chun, W.; Lee, H.J.; Min, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Seo, J.Y.; Ahn, K.S.; Oh, S.R. The Role of Macrophages in the Development of Acute and Chronic Inflammatory Lung Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yao, Z.; Xu, L.; Peng, M.; Deng, G.; Liu, L.; Jiang, X.; Cai, X. M2 macrophage polarization in systemic sclerosis fibrosis: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic effects. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhang, M.; Lei, W.; Yang, R.; Fu, S.; Fan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T. Advances in the role of STAT3 in macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1160719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Li, S.; Chen, H. Macrophages in Lung Injury, Repair, and Fibrosis. Cells 2021, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasse, A.; Probst, C.; Bargagli, E.; Zissel, G.; Toews, G.B.; Flaherty, K.R.; Olschewski, M.; Rottoli, P.; Muller-Quernheim, J. Serum CC-chemokine ligand 18 concentration predicts outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicano, C.; Vantaggio, L.; Colalillo, A.; Pocino, K.; Basile, V.; Marino, M.; Basile, U.; Rosato, E. Type 2 cytokines and scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 3517–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, D.M.; Pioli, P.A. Macrophages in Systemic Sclerosis: Novel Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2019, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, E.; Soldano, S.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Montagna, P.; Campitiello, R.; Contini, P.; Mora, M.; Benelli, R.; Hysa, E.; Paolino, S.; et al. Prevalence of hybrid TLR4(+)M2 monocytes/macrophages in peripheral blood and lung of systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1488867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.; Hu, F.; Xie, L. Macrophage polarization and its impact on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1444964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Ding, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, H.; Luo, H. Contributions of Immune Cells and Stromal Cells to the Pathogenesis of Systemic Sclerosis: Recent Insights. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 826839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, M.; Hukara, A.; Kocherova, I.; Jordan, S.; Schniering, J.; Milleret, V.; Ehrbar, M.; Klingel, K.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Distler, O.; et al. Elevated Fibronectin Levels in Profibrotic CD14(+) Monocytes and CD14(+) Macrophages in Systemic Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 642891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Pei, X.; Peng, J.; Wu, C.; Lv, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, X.; Dong, X.; Zhou, S.; et al. Monocyte-macrophage dynamics as key in disparate lung and peripheral immune responses in severe anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis-related interstitial lung disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyfman, P.A.; Walter, J.M.; Joshi, N.; Anekalla, K.R.; McQuattie-Pimentel, A.C.; Chiu, S.; Fernandez, R.; Akbarpour, M.; Chen, C.I.; Ren, Z.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Human Lung Provides Insights into the Pathobiology of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, H.; Fang, M.; Hang, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Chen, M. Pirfenidone modulates macrophage polarization and ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-beta1/Smad3 pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 8662–8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Ying, L.; Lang, J.K.; Hinz, B.; Zhao, R. Modeling mechanical activation of macrophages during pulmonary fibrogenesis for targeted anti-fibrosis therapy. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescoat, A.; Lelong, M.; Jeljeli, M.; Piquet-Pellorce, C.; Morzadec, C.; Ballerie, A.; Jouneau, S.; Jego, P.; Vernhet, L.; Batteux, F.; et al. Combined anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties of JAK-inhibitors on macrophages in vitro and in vivo: Perspectives for scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombardieri, M.; Lewis, M.; Pitzalis, C. Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.; Griese, M.; Kappler, M.; Zissel, G.; Reinhardt, D.; Rebhan, C.; Schendel, D.J.; Krauss-Etschmann, S. Pulmonary T(H)2 response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Hirahara, K.; Kokubo, K.; Kiuchi, M.; Aoki, A.; Morimoto, Y.; Kumagai, J.; Onodera, A.; Mato, N.; Tumes, D.J.; et al. CD103(hi) T(reg) cells constrain lung fibrosis induced by CD103(lo) tissue-resident pathogenic CD4 T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Tonelli, R.; Samarelli, A.V.; Castelli, G.; Cocconcelli, E.; Petrarulo, S.; Cerri, S.; Bernardinello, N.; Clini, E.; Saetta, M.; et al. The role of immune response in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Far beyond the Th1/Th2 imbalance. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2022, 26, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, K.; Onodera, A.; Kiuchi, M.; Tsuji, K.; Hirahara, K.; Nakayama, T. Conventional and pathogenic Th2 cells in inflammation, tissue repair, and fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 945063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.H.; Yagi, R.; Endo, Y.; Koyama-Nasu, R.; Wang, Y.; Hasegawa, I.; Ito, T.; Junttila, I.S.; Zhu, J.; Kimura, M.Y.; et al. IFNgamma suppresses the expression of GFI1 and thereby inhibits Th2 cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, F.; Ikutani, M.; Seki, Y.; Otsubo, T.; Kawamura, Y.I.; Dohi, T.; Oshima, K.; Hattori, M.; Nakae, S.; Takatsu, K.; et al. Interferon-gamma constrains cytokine production of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunology 2016, 147, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Park, M.K.; Lim, M.A.; Park, E.M.; Kim, E.K.; Yang, E.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Jhun, J.Y.; Park, S.H.; et al. Interferon gamma suppresses collagen-induced arthritis by regulation of Th17 through the induction of indoleamine-2,3-deoxygenase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, S.; Chung, J.H.; Park, W.S.; Chung, D.H. Natural killer T (NKT) cells attenuate bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by producing interferon-gamma. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabarz, F.; Aguiar, C.F.; Correa-Costa, M.; Braga, T.T.; Hyane, M.I.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Landgraf, M.A.; Camara, N.O.S. Protective role of NKT cells and macrophage M2-driven phenotype in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.E., Jr.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; Hormel, P.; Lancaster, L.; Noble, P.W.; Sahn, S.A.; Szwarcberg, J.; Thomeer, M.; et al. Effect of interferon gamma-1b on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (INSPIRE): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieseck, R.L., 3rd; Wilson, M.S.; Wynn, T.A. Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.A.; Zhang, H.; Oak, S.R.; Coelho, A.L.; Herath, A.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lee, J.; Bell, M.; Knight, D.A.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Targeting interleukin-13 with tralokinumab attenuates lung fibrosis and epithelial damage in a humanized SCID idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis model. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodsick, J.E.; Toews, G.B.; Jakubzick, C.; Hogaboam, C.; Moore, T.A.; McKenzie, A.; Wilke, C.A.; Chrisman, C.J.; Moore, B.B. Protection from fluorescein isothiocyanate-induced fibrosis in IL-13-deficient, but not IL-4-deficient, mice results from impaired collagen synthesis by fibroblasts. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 4068–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Mitch, W.E.; Wang, Y. The IL-4 receptor alpha has a critical role in bone marrow-derived fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Martinez-Gamboa, L.; Meier, S.; Witt, C.; Meisel, C.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Becker, M.O.; Huscher, D.; Burmester, G.R.; Riemekasten, G. Bronchoalveoloar lavage fluid cytokines and chemokines as markers and predictors for the outcome of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanore, Y.; Wung, P.; Soubrane, C.; Esperet, C.; Marrache, F.; Bejuit, R.; Lahmar, A.; Khanna, D.; Denton, C.P., On behalf of the Investigators. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 24-week, phase II, proof-of-concept study of romilkimab (SAR156597) in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. T Cells in Fibrosis and Fibrotic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Roden, A.C.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Prakash, Y.S.; Matteson, E.L.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; et al. Profibrotic effect of IL-17A and elevated IL-17RA in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease support a direct role for IL-17A/IL-17RA in human fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2019, 316, L487–L497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senoo, S.; Higo, H.; Taniguchi, A.; Kiura, K.; Maeda, Y.; Miyahara, N. Pulmonary fibrosis and type-17 immunity. Respir. Investig. 2023, 61, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, E.; Fisher, A.J.; Gu, H.; Mickler, E.A.; Agarwal, M.; Wilke, C.A.; Kim, K.K.; Moore, B.B.; Vittal, R. IL-17A deficiency mitigates bleomycin-induced complement activation during lung fibrosis. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 5543–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchetet, M.E.; Brembilla, N.C.; Montanari, E.; Allanore, Y.; Chizzolini, C. Increased frequency of circulating Th22 in addition to Th17 and Th2 lymphocytes in systemic sclerosis: Association with interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, T.K.; Singh, M.; Dhawan, M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Rabaan, A.A.; Mutair, A.A.; Alawi, Z.A.; Alhumaid, S.; Dhama, K. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their therapeutic potential against autoimmune disorders—Advances and challenges. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2035117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienart, S.; Merceron, R.; Vanderaa, C.; Lambert, F.; Colau, D.; Stockis, J.; van der Woning, B.; De Haard, H.; Saunders, M.; Coulie, P.G.; et al. Structural basis of latent TGF-beta1 presentation and activation by GARP on human regulatory T cells. Science 2018, 362, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettelli, E.; Carrier, Y.; Gao, W.; Korn, T.; Strom, T.B.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L.; Kuchroo, V.K. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006, 441, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.O.; Panopoulos, A.D.; Nurieva, R.; Chang, S.H.; Wang, D.; Watowich, S.S.; Dong, C. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9358–9363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Lu, H.; Ichiyama, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.B.; Mistry, N.A.; Tanaka, K.; Lee, Y.H.; Nurieva, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. Generation of RORgammat(+) Antigen-Specific T Regulatory 17 Cells from Foxp3(+) Precursors in Autoimmunity. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovenschen, H.J.; van de Kerkhof, P.C.; van Erp, P.E.; Woestenenk, R.; Joosten, I.; Koenen, H.J. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells of psoriasis patients easily differentiate into IL-17A-producing cells and are found in lesional skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curioni, A.V.; Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Helou, D.G. Updates on the controversial roles of regulatory lymphoid cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1466901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, J.M.; Velegraki, M.; Bolyard, C.; Rosenblum, M.D.; Li, Z. Transforming growth factor-beta1 in regulatory T cell biology. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabi4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, S.R.; Vuga, L.J.; Lindell, K.O.; Gibson, K.F.; Xue, J.; Kaminski, N.; Valentine, V.G.; Lindsay, E.K.; George, M.P.; Steele, C.; et al. CD28 down-regulation on circulating CD4 T-cells is associated with poor prognoses of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Galan, L.; Becerril, C.; Ruiz, A.; Ramon-Luing, L.A.; Cisneros, J.; Montano, M.; Salgado, A.; Ramos, C.; Buendia-Roldan, I.; Pardo, A.; et al. Fibroblasts From Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Induce Apoptosis and Reduce the Migration Capacity of T Lymphocytes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 820347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, T.; Yoshizaki-Ogawa, A.; Sato, S.; Yoshizaki, A. The role of B cells in systemic sclerosis. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, Y.; Ridgway, W.M.; Oriss, T.; Gu, X.; Chin, D.; Wu, Y.; Fertig, N.; Oury, T.; Vandersteen, D.; Clemens, P.; et al. Species-specific immune responses generated by histidyl-tRNA synthetase immunization are associated with muscle and lung inflammation. J. Autoimmun. 2007, 29, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musai, J.; Mammen, A.L.; Pinal-Fernandez, I. Recent Updates on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Myopathies. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2024, 26, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.A.; Pinkus, J.L.; Pinkus, G.S.; Burleson, T.; Sanoudou, D.; Tawil, R.; Barohn, R.J.; Saperstein, D.S.; Briemberg, H.R.; Ericsson, M.; et al. Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Su, M.; Zheng, S.; Lin, J.; Zheng, K.; Shen, F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y. Monocyte-driven IFN and TNF programs orchestrate inflammatory networks in antisynthetase syndrome-associated interstitial lung disease. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1652999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallay, L.; Gayed, C.; Hervier, B. Antisynthetase syndrome pathogenesis: Knowledge and uncertainties. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.M.; Raben, N.; Xie, D.; Askin, F.B.; Tuder, R.; Mullins, M.; Rosen, A.; Casciola-Rosen, L.A. Novel conformation of histidyl-transfer RNA synthetase in the lung: The target tissue in Jo-1 autoantibody-associated myositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, M.; Kaneko, Y. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment strategy for rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihtyanova, S.I.; Denton, C.P. Pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease. J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2020, 5, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Yan, B. Pathogenesis of Anti-melanoma Differentiation-Associated Gene 5 Antibody-Positive Dermatomyositis: A Concise Review With an Emphasis on Type I Interferon System. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 833114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Peng, Q.; Wang, G. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis: Pathogenesis and clinical progress. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Gorycka, A. U1-RNP and Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of mixed connective tissue diseasePart II. Endosomal TLRs and their biological significance in the pathogenesis of mixed connective tissue disease. Reumatologia 2015, 53, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Gorycka, A. U1-RNP and TLR receptors in the pathogenesis of mixed connective tissue diseasePart I. The U1-RNP complex and its biological significance in the pathogenesis of mixed connective tissue disease. Reumatologia 2015, 53, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, V.; Assassi, S.; Allanore, Y.; Kuwana, M.; Denton, C.P.; Khanna, D.; Del Galdo, F. Type 1 interferon activation in systemic sclerosis: A biomarker, a target or the culprit. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2022, 34, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.B.; Gabr, J.B.; Ash, M.; Hosler, G. Anifrolumab in Refractory Dermatomyositis and Antisynthetase Syndrome. Case Rep. Rheumatol. 2025, 2025, 5560523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, R.; Wei, J.; Tang, C.; Wang, J.; Lin, M. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody positive dermatomyositis associated interstitial lung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2024, 18, 17534666241294000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; He, S.; Cai, P. Roles of TRIM21/Ro52 in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1435525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Bernstein, E.J.; Bolster, M.B.; Chung, J.H.; Danoff, S.K.; George, M.D.; Khanna, D.; Guyatt, G.; Mirza, R.D.; Aggarwal, R.; et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Screening and Monitoring of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, R.; Bermea, R.S.; Zhao, S.H.; Montesi, S.B.; Singh, A.; Flashner, B.M.; Synn, A.J.; Munchel, J.K.; Rice, M.B.; Soskis, A.; et al. Association of Anti-Ro52 Seropositive Interstitial Lung Disease With a Higher Risk of Disease Progression and Mortality. Chest 2025, 168, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.L.; Laidlaw, S.M.; Dustin, L.B. TRIM21/Ro52—Roles in Innate Immunity and Autoimmune Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 738473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, G.D.; Mishra, R.; Sharma, N.; Kumawat, K.L.; Basu, A.; Singh, S.K. Regulatory role of TRIM21 in the type-I interferon pathway in Japanese encephalitis virus-infected human microglial cells. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logito, V.; Tjandrawati, A.; Sugianli, A.K.; Tristina, N.; Dewi, S. Diagnostic Performance of Anti-Topoisomerase-I, Anti-Th/To Antibody and Anti-Fibrillarin Using Immunoblot Method in Systemic Sclerosis Related Interstitial Lung Disease Patients. Open Access Rheumatol. 2023, 15, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oostveen, W.M.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; Fehres, C.M. Pathogenic role of anti-nuclear autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis: Insights from other rheumatic diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 328, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki, A.; Yanaba, K.; Ogawa, A.; Asano, Y.; Kadono, T.; Sato, S. Immunization with DNA topoisomerase I and Freund’s complete adjuvant induces skin and lung fibrosis and autoimmunity via interleukin-6 signaling. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Suh, C.H.; Kim, H.A.; Jung, J.Y. Clinical Characteristics of Systemic Sclerosis With Interstitial Lung Disease. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 33, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschi, E.; Privitera, D.; Bodio, C.; Lonati, P.A.; Borghi, M.O.; Ingegnoli, F.; Meroni, P.L.; Chighizola, C.B. Scleroderma-specific autoantibodies embedded in immune complexes mediate endothelial damage: An early event in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, R.; Theander, E.; Sjostrom, B.; Brokstad, K.; Henriksson, G. Autoantibodies present before symptom onset in primary Sjogren syndrome. JAMA 2013, 310, 1854–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbelo, P.D.; Gordon, S.M.; Waldman, M.; Edison, J.D.; Little, D.J.; Stitt, R.S.; Bailey, W.T.; Hughes, J.B.; Olson, S.W. Autoantibodies are present before the clinical diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafyatis, R.; O’Hara, C.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A.; Matteson, E. B cell infiltration in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 3167–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsiero, E.; Nerviani, A.; Bombardieri, M.; Pitzalis, C. Ectopic Lymphoid Structures: Powerhouse of Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Moreno, J.; Hartson, L.; Navarro, C.; Gaxiola, M.; Selman, M.; Randall, T.D. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3183–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, K.; Yanagihara, T.; Matsubara, K.; Kunimura, K.; Suzuki, K.; Tsubouchi, K.; Eto, D.; Ando, H.; Uehara, M.; Ikegame, S.; et al. Mass cytometry identifies characteristic immune cell subsets in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from interstitial lung diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1145814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Yanaba, K.; Kodera, M.; Takehara, K.; Sato, S. Elevated serum BAFF levels in patients with systemic sclerosis: Enhanced BAFF signaling in systemic sclerosis B lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, X.; Zheng, S.; Du, G.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhuang, J.; Lin, J.; Hu, S.; Zheng, K.; et al. Serum B-cell activating factor and lung ultrasound B-lines in connective tissue disease related interstitial lung disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1066111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Mizumaki, K.; Kano, M.; Sawada, T.; Tennichi, M.; Okamura, A.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Iwakura, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; et al. BAFF inhibition attenuates fibrosis in scleroderma by modulating the regulatory and effector B cell balance. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, M.; Fushida, N.; Ikeda, T.; Oishi, K.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Ikawa, Y.; Komuro, A.; Matsushita, T. Cytokine-producing B-cell balance associates with skin fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Xu, Z.; Ren, J. Use of rituximab in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: A narrative review. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1555442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M.; Tudor, V.A.; Saunders, P.; Gibbons, M.A.; Fletcher, S.V.; Denton, C.P.; Hoyles, R.K.; Parfrey, H.; Renzoni, E.A.; Kokosi, M.; et al. Rituximab versus intravenous cyclophosphamide in patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease in the UK (RECITAL): A double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebata, S.; Yoshizaki, A.; Oba, K.; Kashiwabara, K.; Ueda, K.; Uemura, Y.; Watadani, T.; Fukasawa, T.; Miura, S.; Yoshizaki-Ogawa, A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of rituximab in systemic sclerosis (DESIRES): A double-blind, investigator-initiated, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e489–e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furie, R.A.; Rovin, B.H.; Garg, J.P.; Santiago, M.B.; Aroca-Martinez, G.; Zuta Santillan, A.E.; Alvarez, D.; Navarro Sandoval, C.; Lila, A.M.; Tumlin, J.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Obinutuzumab in Active Lupus Nephritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, E.H.; Schaub, J.R.; Decaris, M.; Turner, S.; Derynck, R. TGF-beta as a driver of fibrosis: Physiological roles and therapeutic opportunities. J. Pathol. 2021, 254, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y. The Role of IL-6 in Fibrotic Diseases: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5405–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Type 2 cytokines: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liossis, S.C.; Staveri, C. The Role of B Cells in Scleroderma Lung Disease Pathogenesis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 936182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechman, K.; Dalrymple, A.; Southey-Bassols, C.; Cope, A.P.; Galloway, J.B. A systematic review of CXCL13 as a biomarker of disease and treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2020, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, P.; Milara, J.; Roger, I.; Cortijo, J. Role of JAK/STAT in Interstitial Lung Diseases; Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rackow, A.R.; Nagel, D.J.; McCarthy, C.; Judge, J.; Lacy, S.; Freeberg, M.A.T.; Thatcher, T.H.; Kottmann, R.M.; Sime, P.J. The self-fulfilling prophecy of pulmonary fibrosis: A selective inspection of pathological signalling loops. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 250046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Cui, H.; Liu, G. The Intersection between Immune System and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis-A Concise Review. Fibrosis 2025, 3, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaub, E.A.; Dubey, A.; Imani, J.; Botelho, F.; Kolb, M.R.J.; Richards, C.D.; Ask, K. Overexpression of OSM and IL-6 impacts the polarization of pro-fibrotic macrophages and the development of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Distler, O.; Ryerson, C.J.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Lee, J.S.; Bonella, F.; Bouros, D.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Crestani, B.; Matteson, E.L. Mechanisms of progressive fibrosis in connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodyga, M.; Hinz, B. TGF-beta1—A truly transforming growth factor in fibrosis and immunity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 101, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, K.; Itoh, Y.; Fu, H.; Miyazono, K. Receptor-activated transcription factors and beyond: Multiple modes of Smad2/3-dependent transmission of TGF-beta signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, N.; Sakai, S.; Kitagawa, M. Molecular Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis, with Focus on Pathways Related to TGF-beta and the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.; Woods, E.L.; Dally, J.; Kong, D.; Steadman, R.; Moseley, R.; Midgley, A.C. Myofibroblasts: Function, Formation, and Scope of Molecular Therapies for Skin Fibrosis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharip, A.; Kunz, J. Mechanosignaling via Integrins: Pivotal Players in Liver Fibrosis Progression and Therapy. Cells 2025, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wu, Z.; Phan, S.H. Smad3 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2003, 29, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Moir, L.M.; Black, J.L.; Oliver, B.G.; Burgess, J.K. TGFbeta1 induces IL-6 and inhibits IL-8 release in human bronchial epithelial cells: The role of Smad2/3. J. Cell Physiol. 2010, 225, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Zhou, X.; Jin, X.; Lu, C.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, M.; et al. MDA5 expression is associated with TGF-beta-induced fibrosis: Potential mechanism of interstitial lung disease in anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 2022, 62, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraut, J.; Farge, D.; Jean-Louis, F.; Masse, I.; Grigore, E.I.; Arruda, L.C.; Lamartine, J.; Verrecchia, F.; Michel, L. Transforming growth factor-beta increases interleukin-13 synthesis via GATA-3 transcription factor in T-lymphocytes from patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Mouded, M.; Chambers, D.C.; Martinez, F.J.; Richeldi, L.; Lancaster, L.H.; Hamblin, M.J.; Gibson, K.F.; Rosas, I.O.; Prasse, A.; et al. A Phase IIb Randomized Clinical Study of an Anti-alpha(v)beta(6) Monoclonal Antibody in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskovicova, N.; Petrek, M.; Eickelberg, O.; Heinzelmann, K. Platelet-derived growth factor signaling in the lung. From lung development and disease to clinical studies. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 52, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwicka, A.; Ohba, T.; Trojanowska, M.; Yamakage, A.; Strange, C.; Smith, E.A.; Leroy, E.C.; Sutherland, S.; Silver, R.M. Elevated levels of platelet derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta 1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with scleroderma. J. Rheumatol. 1995, 22, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni, S.S.; Santillo, M.; Bevilacqua, F.; Luchetti, M.; Spadoni, T.; Mancini, M.; Fraticelli, P.; Sambo, P.; Funaro, A.; Kazlauskas, A.; et al. Stimulatory autoantibodies to the PDGF receptor in systemic sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; King, T.E., Jr.; Tinkle, S.S.; Dockstader, K.; Newman, L.S. Human mast cell basic fibroblast growth factor in pulmonary fibrotic disorders. Am. J. Pathol. 1996, 149, 2037–2054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Zeng, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J. Regulation of myofibroblast dedifferentiation in pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, A.; Khanna, D.; Misra, R.; Aggarwal, A. Increased expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. Dermatol. Online J. 2006, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadono, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Kubo, M.; Fujimoto, M.; Tamaki, K. Serum concentrations of basic fibroblast growth factor in collagen diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1996, 35, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Su, N.; Yang, J.; Tan, Q.; Huang, S.; Jin, M.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Luo, F.; et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2020, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Aldweib, K.D.; Rajan, T.; Fanburg, B.L. Upregulated expression of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors by transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) mediates enhanced mitogenic responses to FGFs in cultured human lung fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 251, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; Xu, Y.D.; O’Connor, R.; Duronio, V. Proliferation of pulmonary interstitial fibroblasts is mediated by transforming growth factor-beta1-induced release of extracellular fibroblast growth factor-2 and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 43000–43009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, S.L.; Flower, V.A.; Pauling, J.D.; Millar, A.B. VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distler, O.; Del Rosso, A.; Giacomelli, R.; Cipriani, P.; Conforti, M.L.; Guiducci, S.; Gay, R.E.; Michel, B.A.; Bruhlmann, P.; Muller-Ladner, U.; et al. Angiogenic and angiostatic factors in systemic sclerosis: Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor are a feature of the earliest disease stages and are associated with the absence of fingertip ulcers. Arthritis Res. 2002, 4, R11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollin, L.; Wex, E.; Pautsch, A.; Schnapp, G.; Hostettler, K.E.; Stowasser, S.; Kolb, M. Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; du Bois, R.M.; Raghu, G.; Azuma, A.; Brown, K.K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; Flaherty, K.R.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2071–2082, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distler, O.; Highland, K.B.; Gahlemann, M.; Azuma, A.; Fischer, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Raghu, G.; Sauter, W.; Girard, M.; Alves, M.; et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Wells, A.U.; Cottin, V.; Devaraj, A.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Inoue, Y.; Richeldi, L.; Kolb, M.; Tetzlaff, K.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoneanu, A.; Burlui, A.M.; Macovei, L.A.; Bratoiu, I.; Richter, P.; Rezus, E. Targeting Systemic Sclerosis from Pathogenic Mechanisms to Clinical Manifestations: Why IL-6? Biomedicines 2022, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.T.; Karmouty-Quintana, H.; Melicoff, E.; Le, T.T.; Weng, T.; Chen, N.Y.; Pedroza, M.; Zhou, Y.; Davies, J.; Philip, K.; et al. Blockade of IL-6 Trans signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, F.; Tasaka, S.; Inoue, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Nakano, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Yamada, W.; Shiraishi, Y.; Hasegawa, N.; Fujishima, S.; et al. Role of interleukin-6 in bleomycin-induced lung inflammatory changes in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lauretis, A.; Sestini, P.; Pantelidis, P.; Hoyles, R.; Hansell, D.M.; Goh, N.S.; Zappala, C.J.; Visca, D.; Maher, T.M.; Denton, C.P.; et al. Serum interleukin 6 is predictive of early functional decline and mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. J. Rheumatol. 2013, 40, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Liu, S.; Qiu, Q.; Fu, D.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, L.; Cui, Y.; Ye, S.; Xu, H. Increased serum level of IL-6 predicts poor prognosis in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roofeh, D.; Lin, C.J.F.; Goldin, J.; Kim, G.H.; Furst, D.E.; Denton, C.P.; Huang, S.; Khanna, D.; the focuSSced Investigators. Tocilizumab Prevents Progression of Early Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Lin, C.J.F.; Furst, D.E.; Goldin, J.; Kim, G.; Kuwana, M.; Allanore, Y.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Distler, O.; Shima, Y.; et al. Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 963–974, Erratum in Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Akiyama, M.; Kaneko, Y. Long-term efficacy of sarilumab on the progression of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: The KEIO-RA cohort and literature review. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2025, 43, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuji, N.; Sugiyama, K.; Owada, T.; Arifuku, H.; Koyama, K.; Hirata, H.; Fukushima, Y. Safety of Tocilizumab on Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease. Open Access Rheumatol. 2024, 16, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitamura, Y.; Nunomura, S.; Nanri, Y.; Arima, K.; Yoshihara, T.; Komiya, K.; Fukuda, S.; Takatori, H.; Nakajima, H.; Furue, M.; et al. Hierarchical control of interleukin 13 (IL-13) signals in lung fibroblasts by STAT6 and SOX11. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 14646–14658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.C.; Lee, E.J.; Chang, E.J.; Youn, J.; Ghang, B.; Hong, S.; Lee, C.K.; Yoo, B.; Kim, Y.G. IL-17A(+)GM-CSF(+) Neutrophils Are the Major Infiltrating Cells in Interstitial Lung Disease in an Autoimmune Arthritis Model. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando-Randone, S.; Della-Torre, E.; Balanescu, A. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis: Pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic? J. Scleroderma Relat. Disord. 2021, 6, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Ai, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhou, D.; Hu, L.; Yang, H. IL-17A drives a fibroblast-neutrophil-NET axis to exacerbate immunopathology in the lung with diffuse alveolar damage. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1574246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Guo, Q.; Hu, J.; Li, N.; Gao, R.; Mi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, H.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Janus Kinase Inhibitors for the Management of Interstitial Lung Disease. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2022, 16, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, M.; Fan, G.; Xing, N.; Zhang, R. Effect of Baricitinib on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of alveolar epithelial cells induced by IL-6. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 110, 109044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza, M.; Le, T.T.; Lewis, K.; Karmouty-Quintana, H.; To, S.; George, A.T.; Blackburn, M.R.; Tweardy, D.J.; Agarwal, S.K. STAT-3 contributes to pulmonary fibrosis through epithelial injury and fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, K.M.; Distler, O.; Gheorghiu, A.M.; Moor, C.C.; Vikse, J.; Bizymi, N.; Galetti, I.; Brown, G.; Bargagli, E.; Allanore, Y.; et al. ERS/EULAR clinical practice guidelines for connective tissue diseases associated interstitial lung disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, T.M.; Assassi, S.; Azuma, A.; Cottin, V.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Kreuter, M.; Oldham, J.M.; Richeldi, L.; Valenzuela, C.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; et al. Nerandomilast in Patients with Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, M.; Crestani, B.; Maher, T.M. Phosphodiesterase 4B inhibition: A potential novel strategy for treating pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 220206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Jiao, R.; Wang, Q.; Meng, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; et al. Nerandomilast Improves Bleomycin-Induced Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease in Mice by Regulating the TGF-beta1 Pathway. Inflammation 2025, 48, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.H.; Gao, V.R.; Periyakoil, P.K.; Kochen, A.; DiCarlo, E.F.; Goodman, S.M.; Norman, T.M.; Donlin, L.T.; Leslie, C.S.; Rudensky, A.Y. Drivers of heterogeneity in synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Brown, K.K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; du Bois, R.M.; Lasky, J.A.; Thomeer, M.; Utz, J.P.; Khandker, R.K.; McDermott, L.; et al. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with etanercept: An exploratory, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Nguyen, H.N.; Brenner, M.B. Fibroblast pathology in inflammatory diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e149538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasse, A.; Pechkovsky, D.V.; Toews, G.B.; Jungraithmayr, W.; Kollert, F.; Goldmann, T.; Vollmer, E.; Muller-Quernheim, J.; Zissel, G. A vicious circle of alveolar macrophages and fibroblasts perpetuates pulmonary fibrosis via CCL18. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, E.; Martini, A.; Depascale, R.; Gamba, A.; Tonello, M.; Gatto, M.; Giraudo, C.; Balestro, E.; Doria, A.; Iaccarino, L. CCL18 as a Biomarker of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) and Progressive Fibrosing ILD in Patients with Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, G.; Cameli, P.; Bonella, F. The role of heat shock protein 90 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: State of the art. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 240147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.R.; Chen, L.; Li, C.Q. Ethoxyquin mediates lung fibrosis and cellular immunity in BLM-CIA mice by inhibiting HSP90. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 34, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, H.; Yang, Z.; Qu, J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Update on Pathogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 797292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network; Raghu, G.; Anstrom, K.J.; King, T.E., Jr.; Lasky, J.A.; Martinez, F.J. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1968–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Montesi, S.B.; Silver, R.M.; Hossain, T.; Macrea, M.; Herman, D.; Barnes, H.; Adegunsoye, A.; Azuma, A.; Chung, L.; et al. Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis-associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Evidence-based Recommendations. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, J.; Zhang, X. Factors associated with interstitial lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Ohkubo, H.; Niimi, A.; Kanazawa, S. Suppression of epithelial abnormalities by nintedanib in induced-rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease mouse model. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00345–02021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, Y.H.; Moor, C.C.; Merkt, W.; Buschulte, K.; Zheng, B.; Muller, V.; Kreuter, M. Treating connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease—Think outside the box: A perspective. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 250046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misirci, S.; Ekin, A.; Yagiz, B.; Coskun, B.N.; Basibuyuk, F.; Birlik, A.M.; Sari, I.; Karaca, A.D.; Koca, S.S.; Yildirim Cetin, G.; et al. Treatment with nintedanib is as effective and safe in patients with other connective tissue diseases (CTDs)-interstitial lung disease (ILD) as in patients with systemic sclerosis-ILD: A multicenter retrospective study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 44, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R.; Bernstein, E.J.; Bolster, M.B.; Chung, J.H.; Danoff, S.K.; George, M.D.; Khanna, D.; Guyatt, G.; Mirza, R.D.; Aggarwal, R.; et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 1182–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, S.; Somboonviboon, D.; Scallan, C.; Kolb, M. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An update on emerging drugs in phase II & III clinical trials. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2024, 29, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mediator | Main Source | Role in Pathogenesis | Targeted Therapy | Associated CTDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β [157] | M2 macrophages and epithelial cells | Master profibrotic cytokine; induces fibroblast activation and ECM deposition via SMAD pathway and EMT | No approved direct therapy; hard to block safely | SSc-ILD and myositis-ILD |

| IL-6 [158] | Macrophages, T cells, and B cells | Promotes inflammation, Th17 differentiation, and fibroblast proliferation via STAT3 | Tocilizumab (anti-IL-6R) | SSc-ILD and RA-ILD |

| IL-13 [159] | Th2 cells | Drives M2 macrophage polarization, fibroblast activation, and EMT via STAT6 | Experimental (e.g., anti-IL-13 antibodies and IL-4Rα blockers) | SSc-ILD |

| IL-17 [104] | Th17 cells and γδ T cells | Sustains chronic inflammation and synergizes with TGF-β to induce fibrosis via STAT3 | Under investigation (an anti-IL-17A antibody is not approved for ILD) | SSc and myositis-ILD |

| IFN-γ [88] | Th1 cells and NKT cells | Counterbalances Th2 and Th17 responses; generally, antifibrotic | Not currently used; past trials unsuccessful in IPF | RA and general antifibrotic role |

| BAFF [160] | B cells and dendritic cells | Promotes B cell survival, autoantibody production, and cytokine release (IL-6, IL-10) | Belimumab (anti-BAFF antibody; used in SLE; and explored in SSc) | SSc-ILD, RA-ILD, and Sjogren’s syndrome |

| CXCL13 [161] | Follicular dendritic cells and macrophages | Drives tertiary lymphoid structure formation and recruits B and Tfh cells | None yet; potential biomarker and research target | RA-ILD and Sjogren’s syndrome |

| JAK/STAT [162] | Downstream of IL-6, IL-13, and IFN-γ | Integrates multiple cytokine signals and drives pro-fibrotic immune skewing | JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, baricitinib, and filgotinib) | RA-ILD and myositis-ILD |

| Citrullinated Proteins [28] | Smoking-induced lung cells (RA) and PAD enzymes | Acts as DAMPs, promoting epithelial injury and triggering anti-CCP antibody production | No direct therapy; linked to smoking cessation and autoantibody screening | RA-ILD |

| PDGF (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor) [163] | Activated macrophages, platelets, injured epithelial cells, and fibroblasts | Stimulates fibroblast proliferation, chemotaxis, survival, and ECM production and promotes myofibroblast differentiation and tissue remodeling | Nintedanib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks PDGFR, FGFR, and VEGFR) | CTD-ILD with progressive fibrosis SSc-ILD, and RA-ILD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, S.; Her, M. Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Incessant Loop of Immunity to Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412126

Lee JH, Jang JH, Lee S, Her M. Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Incessant Loop of Immunity to Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412126

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae Ha, Ji Hoon Jang, Sunggun Lee, and Minyoung Her. 2025. "Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Incessant Loop of Immunity to Fibrosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412126

APA StyleLee, J. H., Jang, J. H., Lee, S., & Her, M. (2025). Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Incessant Loop of Immunity to Fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412126