Hypoxic Small Extracellular Vesicle Preconditioning of AC16 Cardiomyocytes Increase Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 Activity During Hypoxia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. AC16 CMs Secrete sEVs into Condition Medium

2.2. Hypoxic Stimulation Increases HIF-1α Expression in AC16

2.3. Hypoxia and H-sEVs Negatively Impact AC16

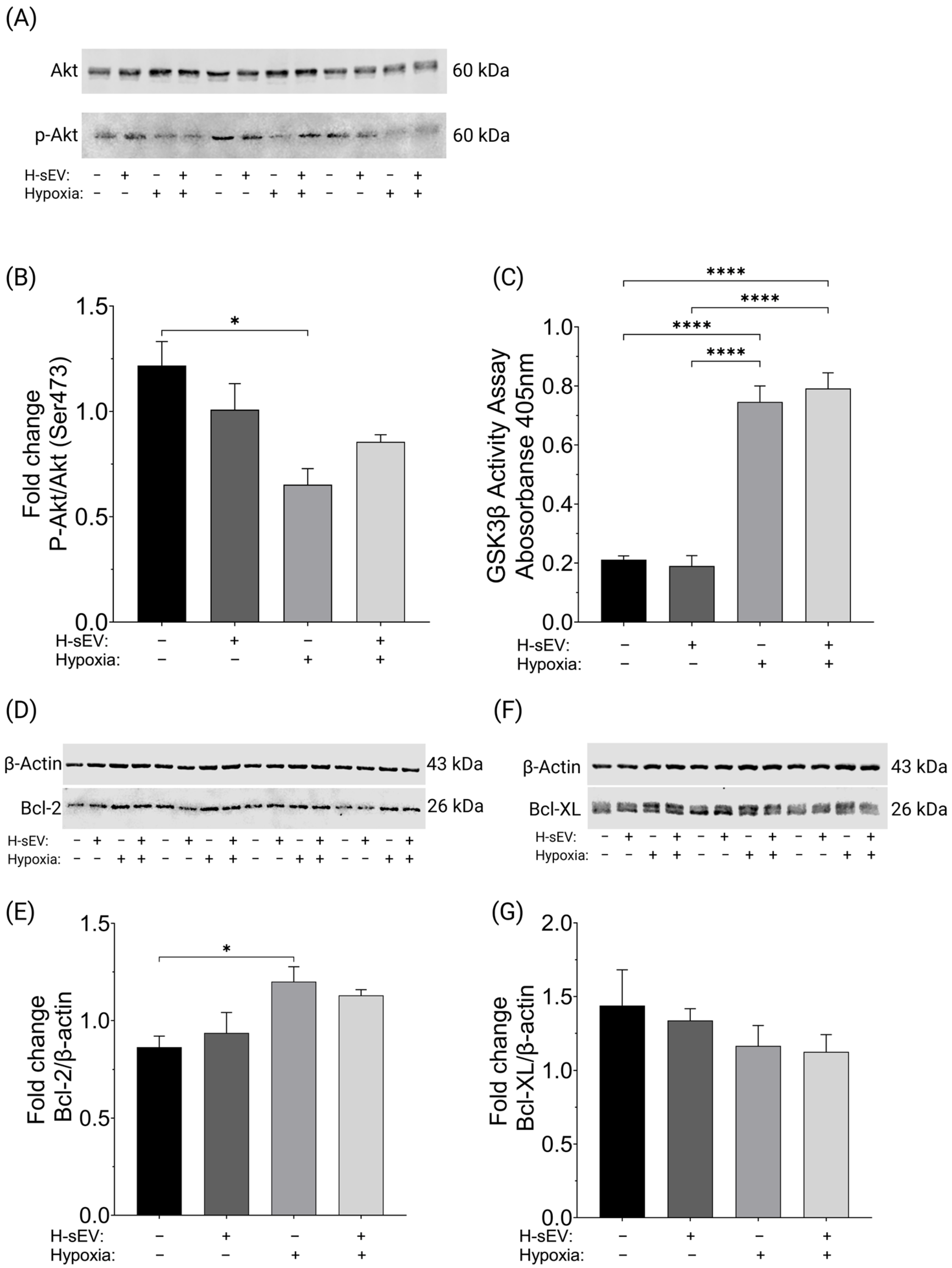

2.4. H-sEV Preconditioning Did Not Affect Akt, GSK3β, Bcl-2, or Bcl-XL Activity

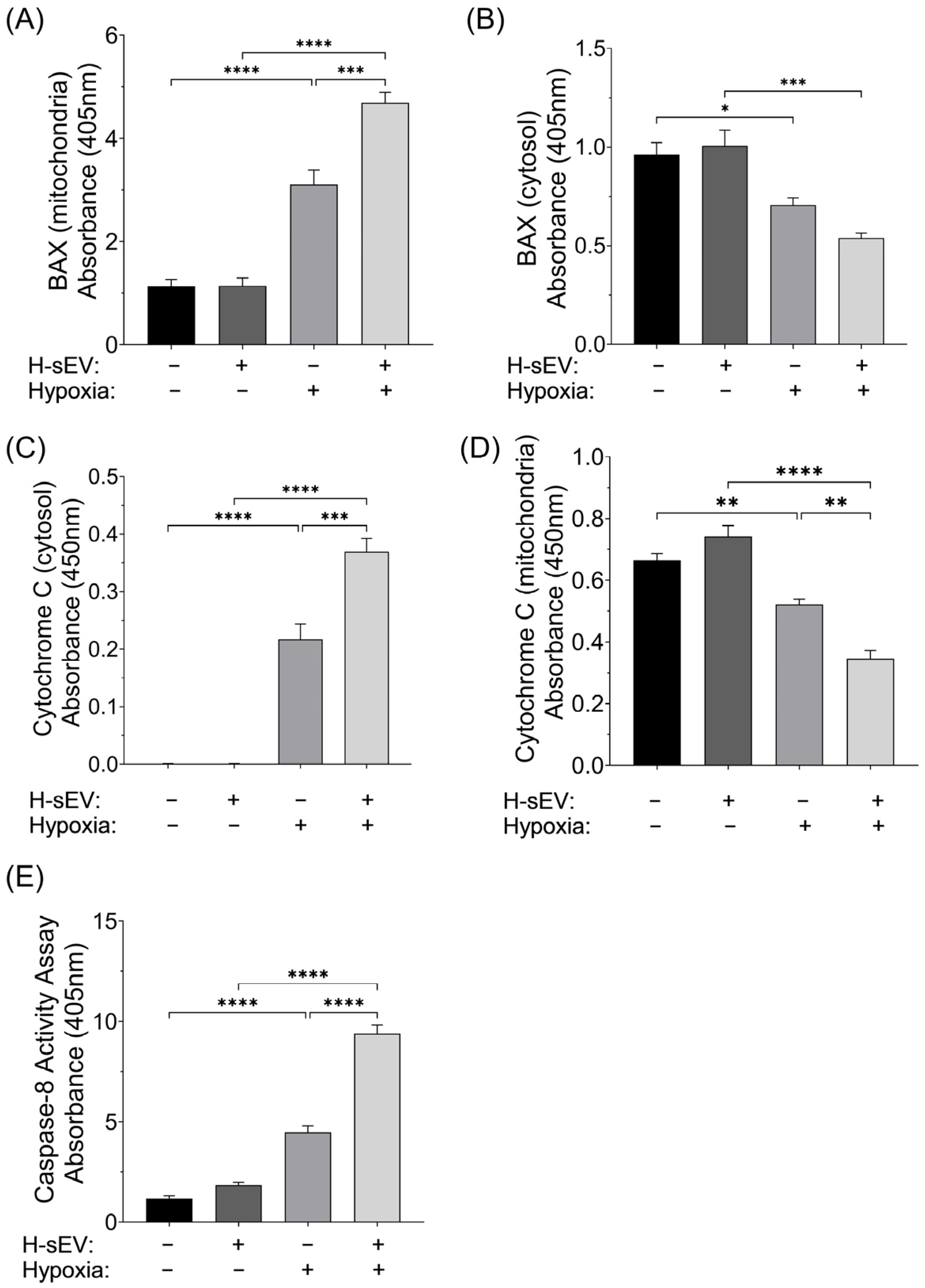

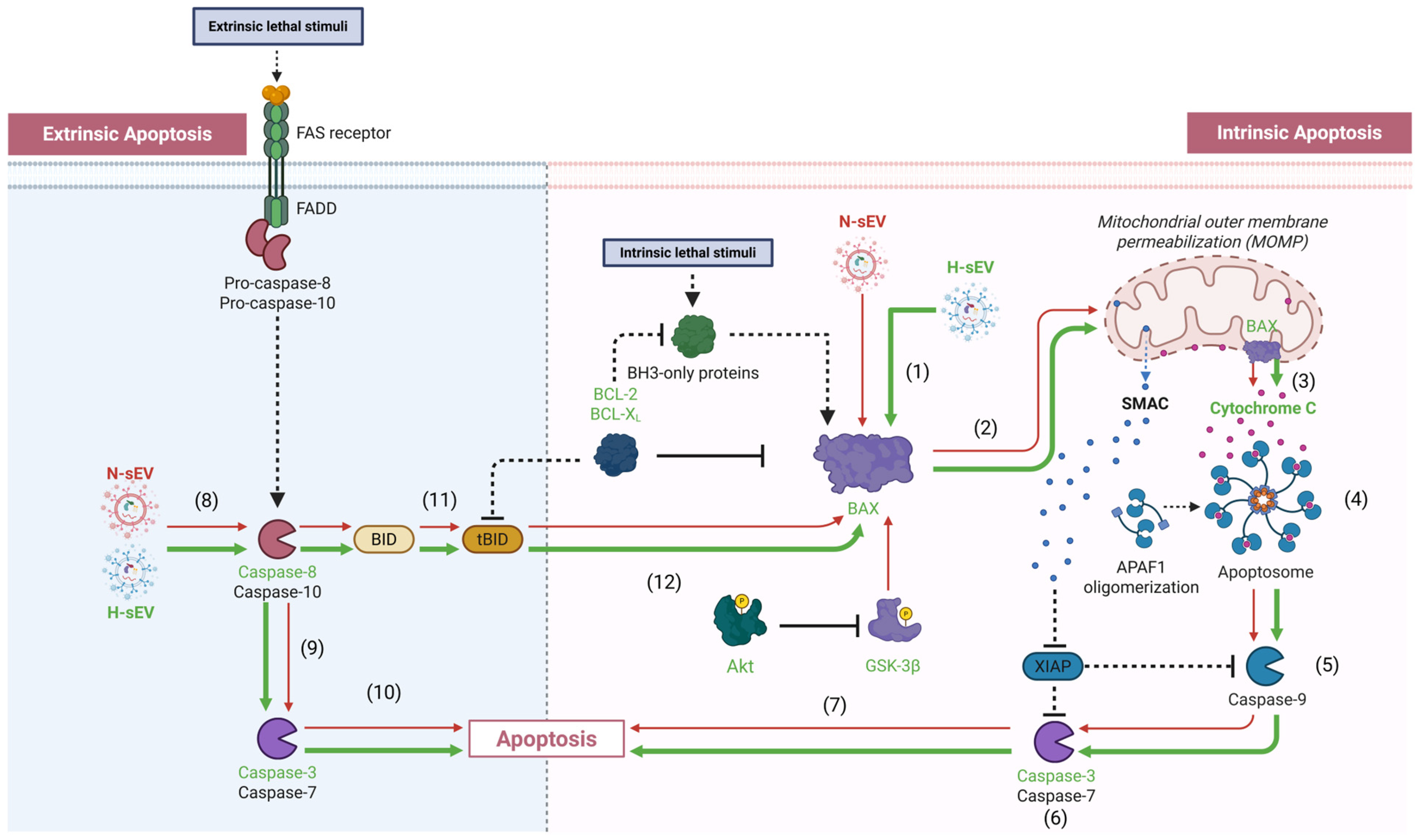

2.5. Pro-Apoptotic Mediator of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AC16 CM Culture and Maintenance

4.2. Generation of sEVs from Normoxic and Hypoxic AC16 CMs

4.3. Isolation and Resuspension of AC16 CM-Derived sEVs

4.4. sEV Quantification and Characterization

4.5. sEV Preconditioning

4.6. Post-Preconditional Normoxic or Hypoxic Stimulation

4.7. Quantitative Measurement of HIF-1α

4.8. PrestoBlue Cell Viability Assay

4.9. Caspase-3 Activity Assay

4.10. Western Blotting in AC16 CMs

4.11. GSK3β Kinase Activity Assay

4.12. Cellular Fractionation to Segregate the Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Compartments

4.13. Validity and Integrity of the Fractionated Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Compartments Subjected to Cytochrome C Release Assay and the Quantitative Sandwich ELISA Immunoassays of BAX

4.14. Quantitative Measurement of the Pro-Apoptotic Protein BAX

4.15. Cytochrome C Release Assay

4.16. Caspase-8 Activity Assay

4.17. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | protein kinase B |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BAK | Bcl2-homologous antagonist/killer |

| BAX | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| CM | cardiomyocyte |

| COX4 | Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit 4 |

| EV | extracellular vesicle |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| H-sEV | hypoxia-derived small extracellular vesicle |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1α |

| MAC | mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel |

| miR | microRNA |

| N-sEV | normoxia-derived small extracellular vesicle |

| NTA | nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| RIPC | remote ischemic preconditioning |

| RISK | reperfusion injury salvage kinase |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

References

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 1841–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.; Coetzee, A.R.; Lochner, A. The Pathophysiology of Myocardial Ischemia and Perioperative Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertracht, O.; Malka, A.; Atar, S.; Binah, O. The mitochondria as a target for cardioprotection in acute myocardial ischemia. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 142, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishopric, N.H.; Andreka, P.; Slepak, T.; Webster, K.A. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis in the cardiac myocyte. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2001, 1, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Kang, P.M. Apoptosis in cardiovascular diseases: Mechanism and clinical implications. Korean Circ. J. 2010, 40, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L.; Nejfelt, M.K.; Chi, S.M.; Antonarakis, S.E. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 5680–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, P.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Chen, C. HIF-1α in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta Chaudhuri, R.; Banik, A.; Mandal, B.; Sarkar, S. Cardiac-specific overexpression of HIF-1α during acute myocardial infarction ameliorates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via differential regulation of hypoxia-inducible pro-apoptotic and anti-oxidative genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 537, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, W.G.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Oxygen Sensing by Metazoans: The Central Role of the HIF Hydroxylase Pathway. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L.; Shimoda, L.A.; Prabhakar, N.R. Regulation of gene expression by HIF-1. In Proceedings of the Signalling Pathways in Acute Oxygen Sensing: Novartis Foundation Symposium 272, Chichester, UK, 25–27 January 2005; pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nowbar, A.N.; Gitto, M.; Howard, J.P.; Francis, D.P.; Al-Lamee, R. Mortality from ischemic heart disease: Analysis of data from the World Health Organization and coronary artery disease risk factors From NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, M.; Evelson, P.; Gelpi, R.J. Protecting the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury: An update on remote ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Mwamure, P.K.; Venugopal, V.; Harris, J.; Barnard, M.; Grundy, E.; Ashley, E.; Vichare, S.; Di Salvo, C.; Kolvekar, S. Effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on myocardial injury in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candilio, L.; Malik, A.; Ariti, C.; Barnard, M.; Di Salvo, C.; Lawrence, D.; Hayward, M.; Yap, J.; Roberts, N.; Sheikh, A. Effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Heart 2015, 101, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhan, H.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is required for remote ischemic preconditioning of the heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17462–17467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausenloy, D.; Iliodromitis, E.; Andreadou, I.; Papalois, A.; Gritsopoulos, G.; Anastasiou-Nana, M.; Kremastinos, D.; Yellon, D. Investigating the signal transduction pathways underlying remote ischemic conditioning in the porcine heart. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2012, 26, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhaszova, M.; Zorov, D.B.; Kim, S.-H.; Pepe, S.; Fu, Q.; Fishbein, K.W.; Ziman, B.D.; Wang, S.; Ytrehus, K.; Antos, C.L. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β mediates convergence of protection signaling to inhibit the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 1535–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.R.; Dudek, H.; Tao, X.; Masters, S.; Fu, H.; Gotoh, Y.; Greenberg, M.E. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell 1997, 91, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.G.; Kandel, E.S.; Cross, T.K.; Hay, N. Akt/Protein kinase B inhibits cell death by preventing the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 5800–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Jope, R.S. The paradoxical pro- and anti-apoptotic actions of GSK3 in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways. Progress. Neurobiol. 2006, 79, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Tsang, A.; Yellon, D.M. The reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway: A common target for both ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2005, 15, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guihard, G.; Bellot, G.; Moreau, C.; Pradal, G.; Ferry, N.; Thomy, R.; Fichet, P.; Meflah, K.; Vallette, F.M. The Mitochondrial Apoptosis-induced Channel (MAC) Corresponds to a Late Apoptotic Event. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 46542–46550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewson, G.; Kluck, R.M. Mechanisms by which Bak and Bax permeabilise mitochondria during apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 2801–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Gong, Z.; Huang, C.; Liang, Q.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Lu, P.; Zhang, B.; Yu, L.; et al. Plasma exosomes induced by remote ischaemic preconditioning attenuate myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury by transferring miR-24. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Lavieu, G.; Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. Cardiac extracellular vesicles in normal and infarcted heart. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zheng, X.-L.; Zhao, S.-P. Exosome and its roles in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.S.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Gho, Y.S. Proteomics of extracellular vesicles: Exosomes and ectosomes. Mass. Spectrom. Rev. 2015, 34, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Record, M.; Carayon, K.; Poirot, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S. Exosomes as new vesicular lipid transporters involved in cell–cell communication and various pathophysiologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallaredy, V.; Roy, R.; Cheng, Z.; Thej, C.; Benedict, C.; Truongcao, M.; Joladarashi, D.; Magadum, A.; Ibetti, J.; Cimini, M.; et al. Tipifarnib Reduces Extracellular Vesicles and Protects From Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Cheng, K. “Tip” the Scale of Cardiac Repair via Reducing Pathological Extracellular Vesicles. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, M.; Raposo, G. Exosomes–vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossello, X.; Yellon, D.M. The RISK pathway and beyond. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 113, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, D.; Kluck, R.M.; Dewson, G. Building blocks of the apoptotic pore: How Bax and Bak are activated and oligomerize during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrenius, S. Mitochondrial regulation of apoptotic cell death. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 149, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Tao, J.; del Monte, F.; Lee, K.-H.; Li, L.; Picard, M.; Force, T.L.; Franke, T.F.; Hajjar, R.J.; Rosenzweig, A. Akt activation preserves cardiac function and prevents injury after transient cardiac ischemia in vivo. Circulation 2001, 104, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Chen, F.; Li, L. Role of glycogen synthase kinase following myocardial infarction and ischemia-reperfusion. Apoptosis 2019, 24, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwarha, G.; Røsand, Ø.; Slagsvold, K.H.; Høydal, M.A. GSK3β Inhibition Is the Molecular Pivot That Underlies the Mir-210-Induced Attenuation of Intrinsic Apoptosis Cascade during Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; Kuno, A.; Ishikawa, S.; Miki, T.; Kouzu, H.; Yano, T.; Murase, H.; Tobisawa, T.; Ogasawara, M.; Horio, Y.; et al. Translocation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), a trigger of permeability transition, is kinase activity-dependent and mediated by interaction with voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (VDAC2). J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29285–29296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, B.; Wang, P.; Keeble, J.A.; Rodriguez-Enriquez, R.; Walker, S.; Owens, T.W.; Foster, F.; Tanianis-Hughes, J.; Brennan, K.; Streuli, C.H.; et al. Bax Exists in a Dynamic Equilibrium between the Cytosol and Mitochondria to Control Apoptotic Priming. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitz, A.Z.; Gavathiotis, E. Physiological and pharmacological modulation of BAX. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locksley, R.M.; Killeen, N.; Lenardo, M.J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: Integrating mammalian biology. Cell 2001, 104, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajant, H. The Fas signaling pathway: More than a paradigm. Science 2002, 296, 1635–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kischkel, F.C.; Hellbardt, S.; Behrmann, I.; Germer, M.; Pawlita, M.; Krammer, P.H.; Peter, M.E. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 5579–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.B.; Freel, C.D.; Kornbluth, S. Cellular mechanisms controlling caspase activation and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Budihardjo, I.; Zou, H.; Slaughter, C.; Wang, X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell 1998, 94, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Long, K.; Qiu, W.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liu, C.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, A.; Jin, L.; et al. Overexpression of Exosomal Cardioprotective miRNAs Mitigates Hypoxia-Induced H9c2 Cells Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chang, S.; Xu, R.; Chen, L.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Qian, J.; Zou, Y.; Ma, J. Hypoxia-challenged MSC-derived exosomes deliver miR-210 to attenuate post-infarction cardiac apoptosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, X.; Lu, C.; Xu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, X.; Song, H.; Chen, A.; Xiong, J.; Wang, K.; et al. Loss of exosomal LncRNA HCG15 prevents acute myocardial ischemic injury through the NF-κB/p65 and p38 pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Exosomal lncRNA AK139128 Derived from Hypoxic Cardiomyocytes Promotes Apoptosis and Inhibits Cell Proliferation in Cardiac Fibroblasts. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3363–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Liao, Y.; Yu, X. Exosomal transfer of miR-30a between cardiomyocytes regulates autophagy after hypoxia. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røsand, Ø.; Wang, J.; Scrimgeour, N.; Marwarha, G.; Høydal, M.A. Exosomal Preconditioning of Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes Beneficially Alters Cardiac Electrophysiology and Micro RNA Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 84600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, M.M.; Nesti, C.; Palenzuela, L.; Walker, W.F.; Hernandez, E.; Protas, L.; Hirano, M.; Isaac, N.D. Novel cell lines derived from adult human ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005, 39, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwarha, G.; Røsand, Ø.; Scrimgeour, N.; Slagsvold, K.H.; Høydal, M.A. miR-210 regulates apoptotic cell death during cellular hypoxia and reoxygenation in a diametrically opposite manner. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Zhong, J.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in human AC16 cardiomyocytes is modulated by AXIN1 depending on c-Myc regulation. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 4844–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Chae, M.; Krishnakumar, R.; Danko, C.G.; Kraus, W.L. Dynamic reorganization of the AC16 cardiomyocyte transcriptome in response to TNFα signaling revealed by integrated genomic analyses. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, P.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Jose, S.; Law, J.X.; Ruszymah, B.H.I.; Mohd Ramzisham, A.R.; Ng, M.H. Development of an In Vitro Cardiac Ischemic Model Using Primary Human Cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, C.; Schmitz, I.; Krammer, P.H.; Peter, M.E. The role of c-FLIP in modulation of CD95-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Fritsch, E.; Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 1.90; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Woodbury, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| Antibody | Application | Amount | Host | Manufacturer | Catalogue # | Resource Identifier ID (RRID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akt | Western Blot | 1:1000 Dilution | Mouse | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 2920 | AB_1147620 |

| Phospho-Akt (Ser473) | Western Blot | 1:1000 Dilution | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 9271 | AB_329825 |

| β-Actin | Western Blot | 1:5000 Dilution | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) | sc-47778 | AB_2714189 |

| β-Actin | ELISA Capture | 20 ng/well | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) | sc-47778 | AB_2714189 |

| β-Actin | ELISA Detection | 20 ng/well | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 4970 | AB_2223172 |

| β-Actin antibody-blocking peptide | ELISA Detection | N/A | N/A | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 1025 | N/A |

| BAX | ELISA Capture | 20 ng/well | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Oslo, Norway) | 33-6600 | AB_2533133 |

| BAX | ELISA Detection | 20 ng/well | Rabbit | Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA) | NBP1-88682 | AB_11014342 |

| BAX antibody-blocking peptide | ELISA Detection | N/A | N/A | Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA) | NBP1-88682PEP | N/A |

| Bcl-XL | Western Blot | 1:1000 Dilution | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 2764 | N/A |

| Bcl-2 | Western Blot | 1:500 Dilution | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Oslo, Norway) | BMS1028 | AB_10597451 |

| COX4 | ELISA Capture | 20 ng/well | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Oslo, Norway) | MA5-15686 | AB_10977841 |

| COX4 | ELISA Detection | 20 ng/well | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 4844 | AB_2085427 |

| COX4 antibody-blocking peptide | ELISA Detection | N/A | N/A | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 1034 | N/A |

| Cytochrome C | ELISA Capture | 20 ng/well | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Oslo, Norway) | BMS1037 | AB_10598651 |

| Cytochrome C | ELISA Detection | 20 ng/well | Rabbit | Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) | 4280 | AB_10695410 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L)-HRP Conjugate | ELISA | N/A € | Goat | Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) | 1706515 | AB_11125142 |

| HIF-1α | ELISA capture | 30 ng/well | Mouse | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Oslo, Norway) | MA1-16504 | AB_568567 |

| HIF-1α | ELISA detection | 20 ng/well | Rabbit | Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA) | NBP1-47180 | AB_10010137 |

| HIF-1α antibody-blocking peptide | ELISA detection | N/A | N/A | Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA) | NBP1-47180PEP | N/A |

| IRDye® 800CW Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody | Western Blot | 1:20,000 Dilution | Goat | LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA) | 926-32210 | N/A |

| IRDye® 800CW Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody | Western Blot | 1:20,000 Dilution | Goat | LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA) | 926-32211 | N/A |

| IRDye® 680RD Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody | Western Blot | 1:20,000 Dilution | Goat | LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA) | 926-68070 | N/A |

| IRDye® 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Secondary Antibody | Western Blot | 1:20,000 Dilution | Goat | LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA) | 926-68071 | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Røsand, Ø.; Johansen, V.; Marwarha, G.; Høydal, M.A. Hypoxic Small Extracellular Vesicle Preconditioning of AC16 Cardiomyocytes Increase Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 Activity During Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412123

Røsand Ø, Johansen V, Marwarha G, Høydal MA. Hypoxic Small Extracellular Vesicle Preconditioning of AC16 Cardiomyocytes Increase Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 Activity During Hypoxia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412123

Chicago/Turabian StyleRøsand, Øystein, Victoria Johansen, Gurdeep Marwarha, and Morten A. Høydal. 2025. "Hypoxic Small Extracellular Vesicle Preconditioning of AC16 Cardiomyocytes Increase Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 Activity During Hypoxia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412123

APA StyleRøsand, Ø., Johansen, V., Marwarha, G., & Høydal, M. A. (2025). Hypoxic Small Extracellular Vesicle Preconditioning of AC16 Cardiomyocytes Increase Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 Activity During Hypoxia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412123