Inflammatory and Neurotrophic Factors and Their Connection to Quality of Life in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy—Single-Center Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

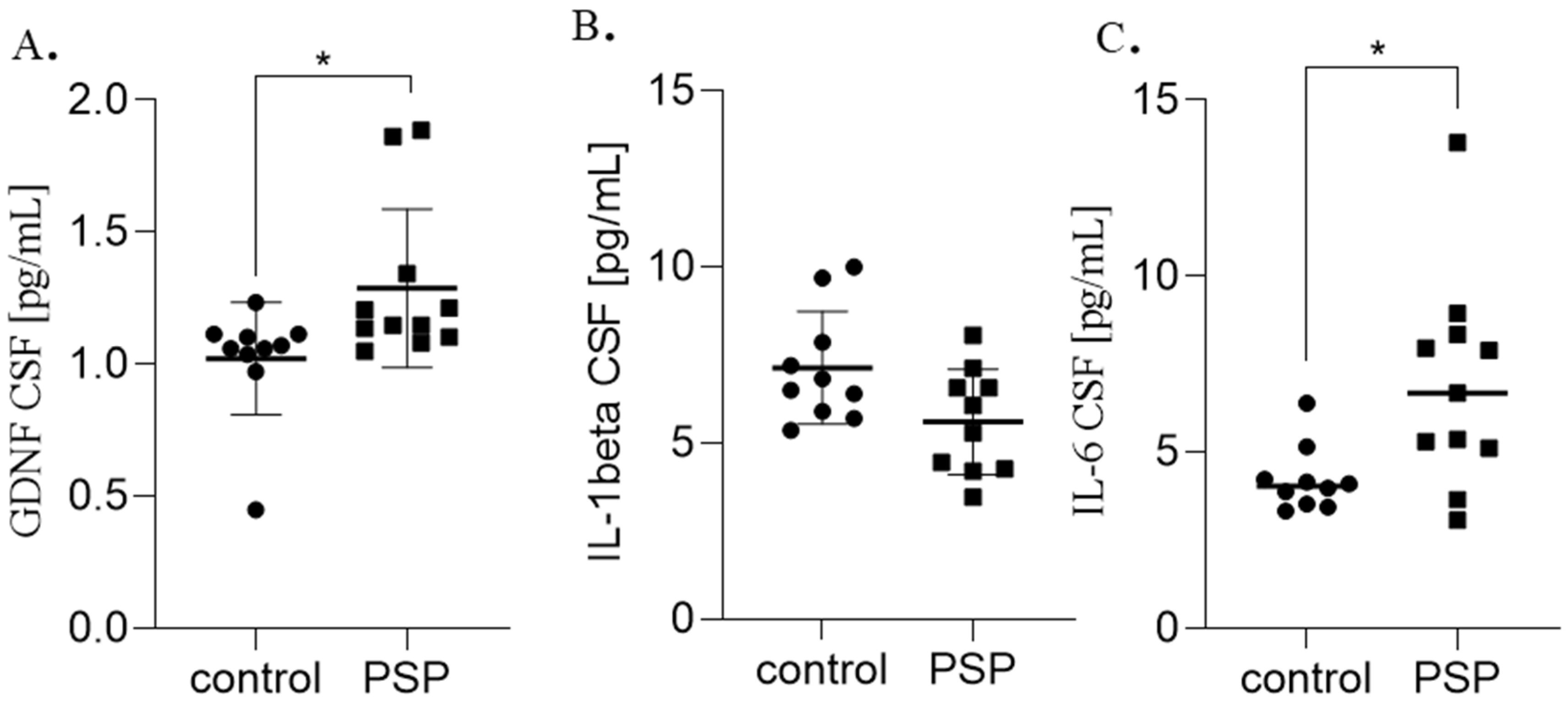

2.1. Biomarker Concentrations in Serum and CSF

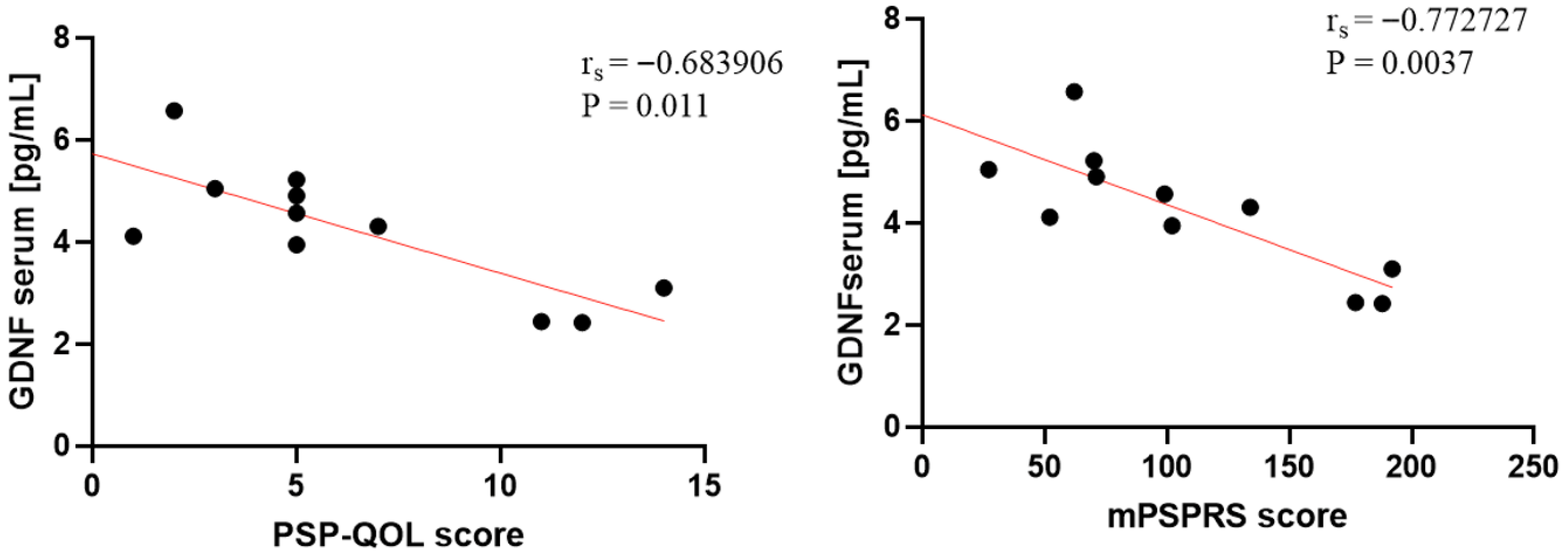

2.2. Correlations Between Biomarkers and Clinical Scales

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Group Description and Examination Methods

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Höglinger, G.U.; Respondek, G.; Stamelou, M.; Kurz, C.; Josephs, K.A.; Lang, A.E.; Mollenhauer, B.; Müller, U.; Nilsson, C.; Whitwell, J.L.; et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2017, 32, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauw, J.J.; Daniel, S.E.; Dickson, D.; Horoupian, D.S.; Jellinger, K.; Lantos, P.L.; McKee, A.; Tabaton, M.; Litvan, I. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology 1994, 44, 2015–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boxer, A.L.; Yu, J.-T.; Golbe, L.I.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; Höglinger, G.U. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: New diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosier, F.; Hibbs, C.; Alessi, K.; Padda, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Pradeep, S.; Parmar, M.S. Progressive supranuclear palsy: Neuropathology, clinical presentation, diagnostic challenges, management, and emerging therapies. Dis. Mon. 2024, 70, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fołta, J.; Rzepka, Z.; Wrzesniok, D. The Role of Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, F.; Johanson, G.A.S.; Tysnes, O.B.; Alves, G.; Dölle, C.; Tzoulis, C. Brain Proteome Profiling Reveals Common and Divergent Sig-natures in Parkinson’s Disease, Multiple System Atrophy, and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 2801–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Block, M.L.; Hong, J.S. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neuro-degeneration: Multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 76, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Botran, R.; Ahmed, Z.; Crespo, F.A.; Gatenbee, C.; Gonzalez, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Litvan, I. Cytokine expression and microglial activation in progressive supranuclear palsy. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizawa, K.; Dickson, D.W. Microglial activation parallels system degeneration in progressive supranuclear palsy and cor-ticobasal degeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 60, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpetti, M.; Passamonti, L.; Rittman, T.; Jones, P.S.; Rodríguez, P.V.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Hong, Y.T.; Fryer, T.D.; Aigbirhio, F.I.; O’Brien, J.T.; et al. Neuroinflammation and tau colocalize in vivo in progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann. Neurol. 2020, 88, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpetti, M.; Passamonti, L.; Jones, P.S.; Street, D.; Rittman, T.; Fryer, T.D.; Hong, Y.T.; Vàsquez Rodriguez, P.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Aigbirhio, F.I.; et al. Neuroinflammation predicts disease progression in progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleis, C.; Sauerbeck, J.; Beyer, L.; Harris, S.; Schmitt, J.; Morenas-Rodriguez, E.; Finze, A.; Nitschmann, A.; Ruch-Rubinstein, F.; Eckenweber, F.; et al. In vivo assessment of neuroinflammation in 4-repeat tauopathies. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, I.; Jimenez, J.M.; Mancilla, M.; Maccioni, R.B. Tau oligomers and fibrils induce activation of microglial cells. J. Alz-Heimers Dis. 2013, 37, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorlovoy, P.; Larionov, S.; Pham, T.T.; Neumann, H. Accumulation of tau induced in neurites by microglial proinflammatory mediators. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 2502–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziorowski, D.; Figura, M.; Milanowski, Ł.M.; Szlufik, S.; Alster, P.; Madetko, N.; Friedman, A. Mechanisms of Neurodegener-ation in Various Forms of Parkinsonism-Similarities and Differences. Cells 2021, 10, 656. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. Evidence and perspectives of cell senescence in neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, C.; Dorothée, G.; Hunot, S.; Martin, E.; Monnet, Y.; Duchamp, M.; Dong, Y.; Légeron, F.-P.; Leboucher, A.; Burnouf, S.; et al. Hippocampal T cell infiltration promotes neuroinflammation and cognitive decline in a mouse model of tauopathy. Brain 2017, 140, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alster, P.; Otto-Ślusarczyk, D.; Wiercińska-Drapało, A.; Struga, M.; Madetko-Alster, N. The potential significance of hepcidin evaluation in progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufson, E.J.; Counts, S.E.; Fahnestock, M.; Ginsberg, S.D. Cholinotrophic molecular substrates of mild cognitive impair-ment in the elderly. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2007, 4, 340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Wuu, J.; Mufson, E.J.; Fahnestock, M. Precursor form of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor are decreased in the pre-clinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2005, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahnestock, M.; Michalski, B.; Xu, B.; Coughlin, M.D. The precursor pro-nerve growth factor is the predominant form of nerve growth factor in brain and is increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2001, 18, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villares, J.; Strada, O.; Faucheux, B.; Javoy-Agid, F.; Agid, Y.; Hirsch, E.C. Loss of striatal high affinity NGF binding sites in progres-sive supranuclear palsy but not in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 182, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.Y.; Wang, R.-W.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yao, X.-Y.; Geng, D.-Q.; Gao, D.-S.; Ren, C. Serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) a potential biomarker of executive function in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1136499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrión, O.; Romero-Gutiérrez, E.; Ortega-Robles, E. Toward Biology-Driven Diagnosis of Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alster, P.; Otto-Ślusarczyk, D.; Szlufik, S.; Duszyńska-Wąs, K.; Drzewińska, A.; Wiercińska-Drapało, A.; Struga, M.; Kutyłowski, M.; Friedman, A.; Madetko-Alster, N. The significance of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor analysis in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Chen, G.; Geng, D.; Gao, D. Low levels of adenosine and GDNF are potential risk factors for Parkinson’s disease with sleep disorders. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Kajihara, R. Neurotrophins and other growth factors in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Life 2023, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alster, P.; Madetko, N.; Koziorowski, D.; Friedman, A. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy-parkinsonism predominant (PSP-P)-A clinical challenge at the boundaries of PSP and parkinson’s disease (PD). Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madetko-Alster, N.; Otto-Slusarczyk, D.; Wiercinska-Drapało, A.; Koziorowski, D.; Szlufik, S.; Samborska-Cwik, J.; Struga, M.; Friedman, A.; Alster, P. Clinical Phenotypes of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy-The Differences in Interleukin Patterns. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, L.; Palazzo, I.; Suarez, L.; Liu, X.; Volkov, L.; Hoang, T.V.; Campbell, W.A.; Blackshaw, S.; Quan, N.; Fischer, A.J. Reactive microglia and IL1/IL-1R1-signaling mediate neuroprotection in excitotoxin-damaged mouse retina. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, E.F.; MacDonald, K.P.A.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Garrido, A.L.; Gillespie, E.R.; Harley, S.B.R.; Bartlett, P.F.; Schroder, W.A.; Yates, A.G.; Anthony, D.C.; et al. Repopulating Microglia Promote Brain Repair in an IL-6-Dependent Manner. Cell 2020, 180, 833–846.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Pei, L.; Yao, S.; Wu, Y.; Shang, Y. NLRP3 Inflammasome in Neurological Diseases, from Functions to Therapies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madetko, N.; Migda, B.; Alster, P.; Turski, P.; Koziorowski, D.; Friedman, A. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophilto-lymphocyte ratio may reflect differences in PD and MSA-P neuroinflammation patterns. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2022, 56, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorova, Y.A.; Saarma, M. Small Molecules and Peptides Targeting Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Receptors for the Treatment of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoshida, M. Astrocytic inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Neuropathology 2014, 34, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Delgado, L.; Luque-Ambrosiani, A.; Zamora, B.B.; Macías-García, D.; Jesús, S.; Adarmes-Gómez, A.; Ojeda-Lepe, E.; Car-rillo, F.; Mir, P. Peripheral immune profile and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in progressive supranuclear palsy: Case-control study and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16451. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.; Janelidze, S.; Surova, Y.; Widner, H.; Zetterberg, H.; Hansson, O. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of inflammatory markers in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonian disorders. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigase, F.A.J.; Smith, E.; Collins, B.; Moore, K.; Snijders, G.J.L.J.; Katz, D.; Bergink, V.; Perez-Rodriquez, M.M.; De Witte, L.D. The association between inflammatory markers in blood and cerebrospinal fluid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1502–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hartikainen, P.; Reinikainen, K.J.; Soininen, H.; Sirviö, J.; Soikkeli, R.; Riekkinen, P.J. Neurochemical markers in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and normal controls. J. Neural Transm. Park. Dis. Dement. Sect. 1992, 4, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbimbo, B.P.; Ippati, S.; Watling, M.; Balducci, C. A critical appraisal of tautargeting therapies for primary and secondary tauopathies. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 1008–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.J.; Watson, J.J.; Shoemark, D.K.; Barua, N.U.; Patel, N.K. GDNF, NGF and BDNF as therapeutic options for neurodegeneration. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biomarker | Control (Means ± SD) | PSP (Mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | |||

| GDNF pg/mL | 1.60 ± 0.6 | 2.23 ± 1.2 | **** p = 0.0001 |

| Hepcidin ng/mL | 0.85 ± 0.1 | 1.88 ± 1.3 | **** p = 0.0001 |

| IL-1 beta pg/mL | 1.62 ± 0.8 | 3.06 ± 1.5 | * p = 0.01 |

| IL-6 pg/mL | 3.72 ± 2.2 | 4.81 ± 2.1 | * p = 0.04 |

| CSF | |||

| GDNF pg/mL | 1.02 ± 0.2 | 1.28 ± 0.3 | * p = 0.01 |

| IL-1 beta pg/mL | 7.14 ± 1.6 | 6.19 ± 1.5 | p = 0.07 |

| IL-6 pg/mL | 4.21 ± 0.9 | 6.92 ± 2.9 | * p = 0.01 |

| Group | Clinical Scale | Biomarker | Specimen | Spearman’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | mPSPRS | GDNF | Serum | −0.772727 | ** p = 0.003 |

| PSP | PSP-QoL | GDNF | Serum | −0.683906 | * p = 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markiewicz, M.; Migda, B.; Otto-Ślusarczyk, D.; Madetko-Alster, N.; Wiercińska-Drapało, A.; Darewicz, M.; Struga, M.; Alster, P. Inflammatory and Neurotrophic Factors and Their Connection to Quality of Life in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy—Single-Center Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412122

Markiewicz M, Migda B, Otto-Ślusarczyk D, Madetko-Alster N, Wiercińska-Drapało A, Darewicz M, Struga M, Alster P. Inflammatory and Neurotrophic Factors and Their Connection to Quality of Life in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy—Single-Center Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412122

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkiewicz, Michał, Bartosz Migda, Dagmara Otto-Ślusarczyk, Natalia Madetko-Alster, Alicja Wiercińska-Drapało, Maciej Darewicz, Marta Struga, and Piotr Alster. 2025. "Inflammatory and Neurotrophic Factors and Their Connection to Quality of Life in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy—Single-Center Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412122

APA StyleMarkiewicz, M., Migda, B., Otto-Ślusarczyk, D., Madetko-Alster, N., Wiercińska-Drapało, A., Darewicz, M., Struga, M., & Alster, P. (2025). Inflammatory and Neurotrophic Factors and Their Connection to Quality of Life in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy—Single-Center Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412122