Critical-Size Muscle Defect Regeneration Using an Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix: An Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culture Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

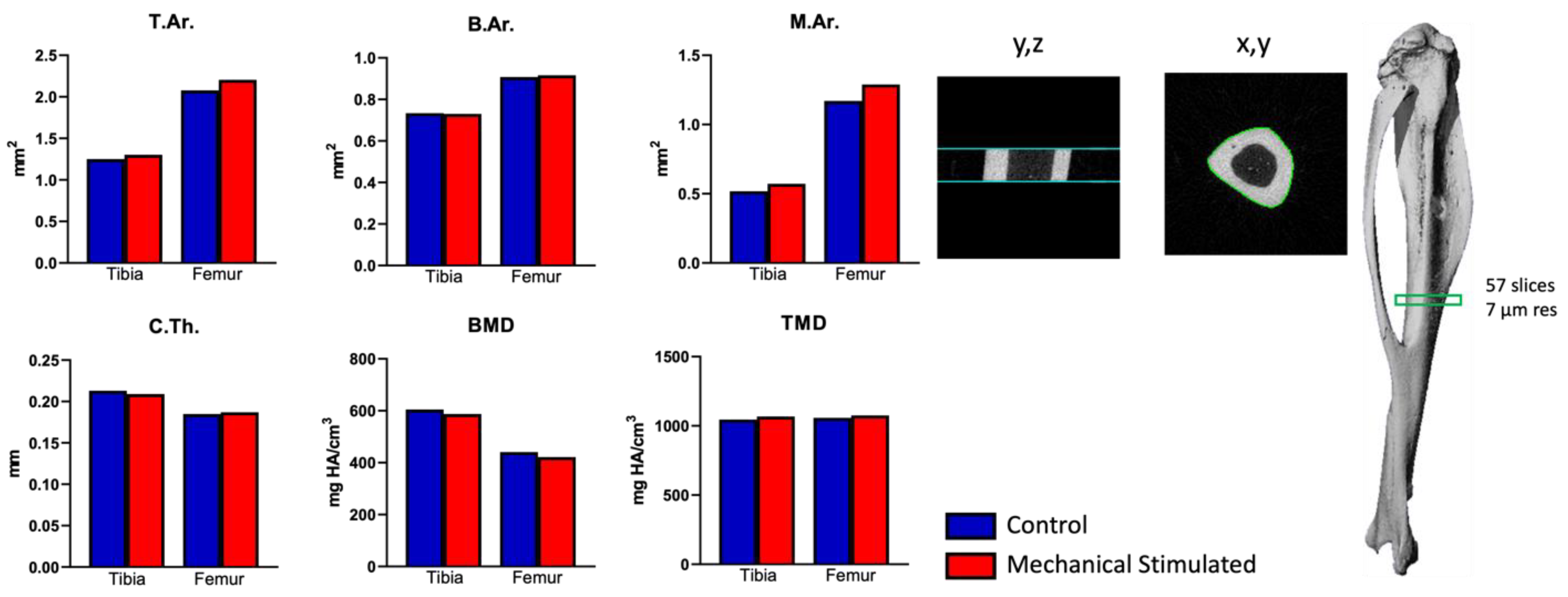

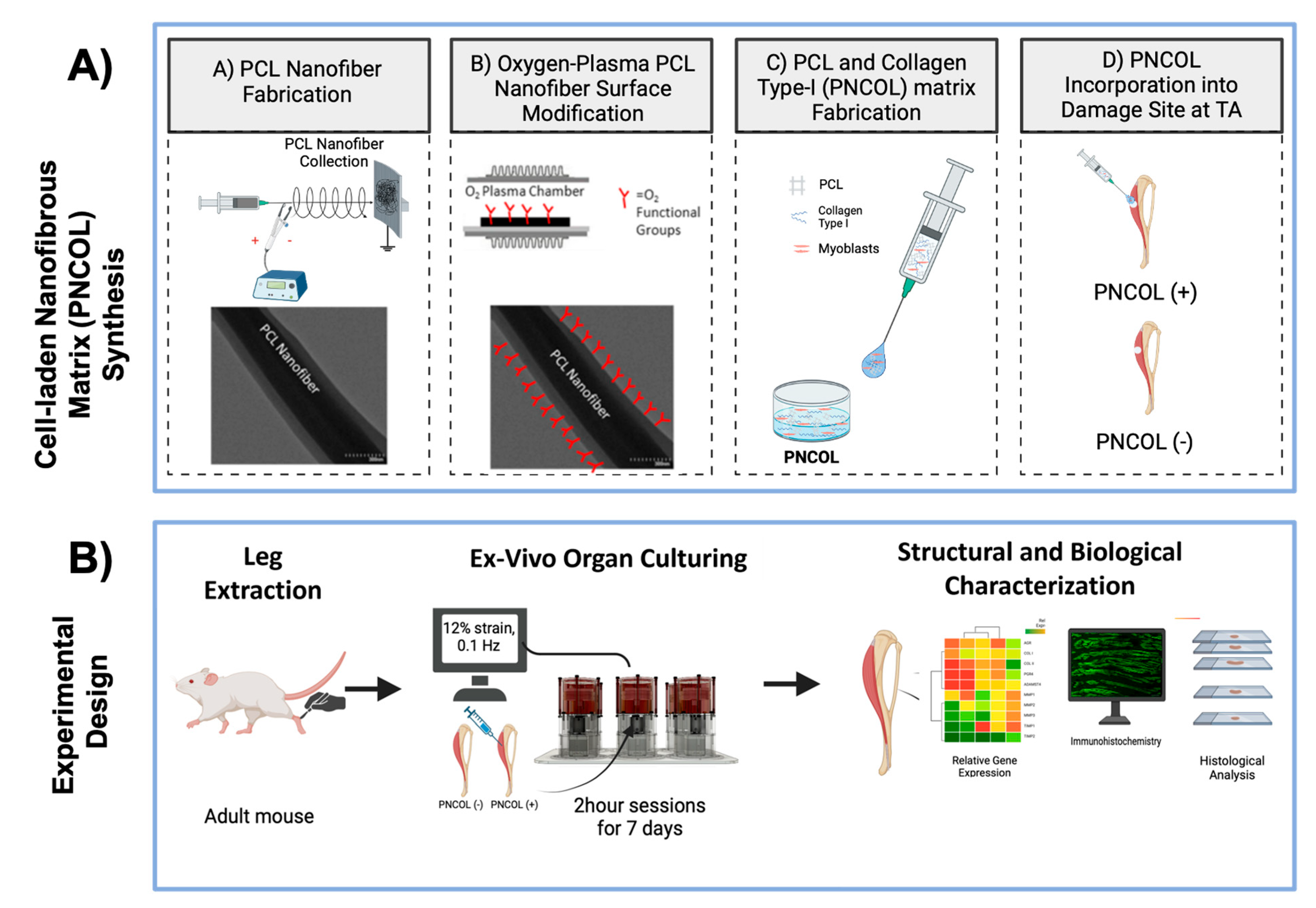

2.1. Ex Vivo Organ Culture Platform Efficiency on Whole Mouse Hindlimbs

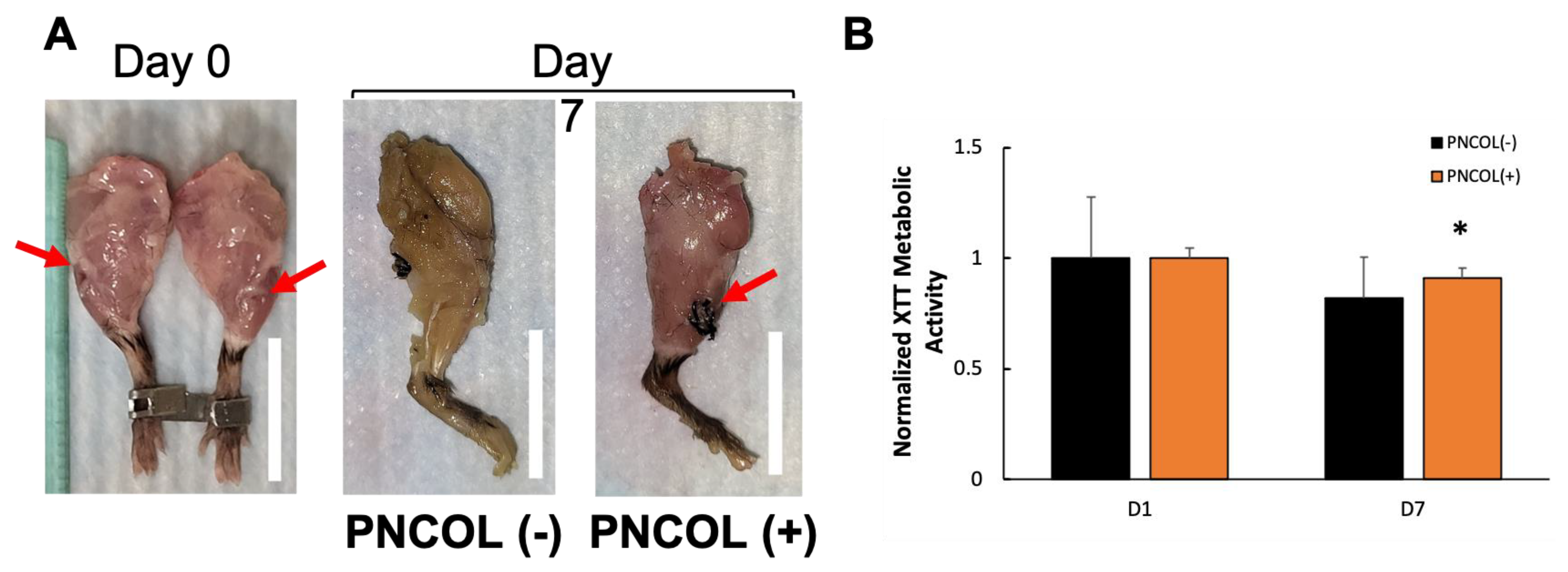

2.2. Cell Viability Within the Mouse Hindlimb After Treatments

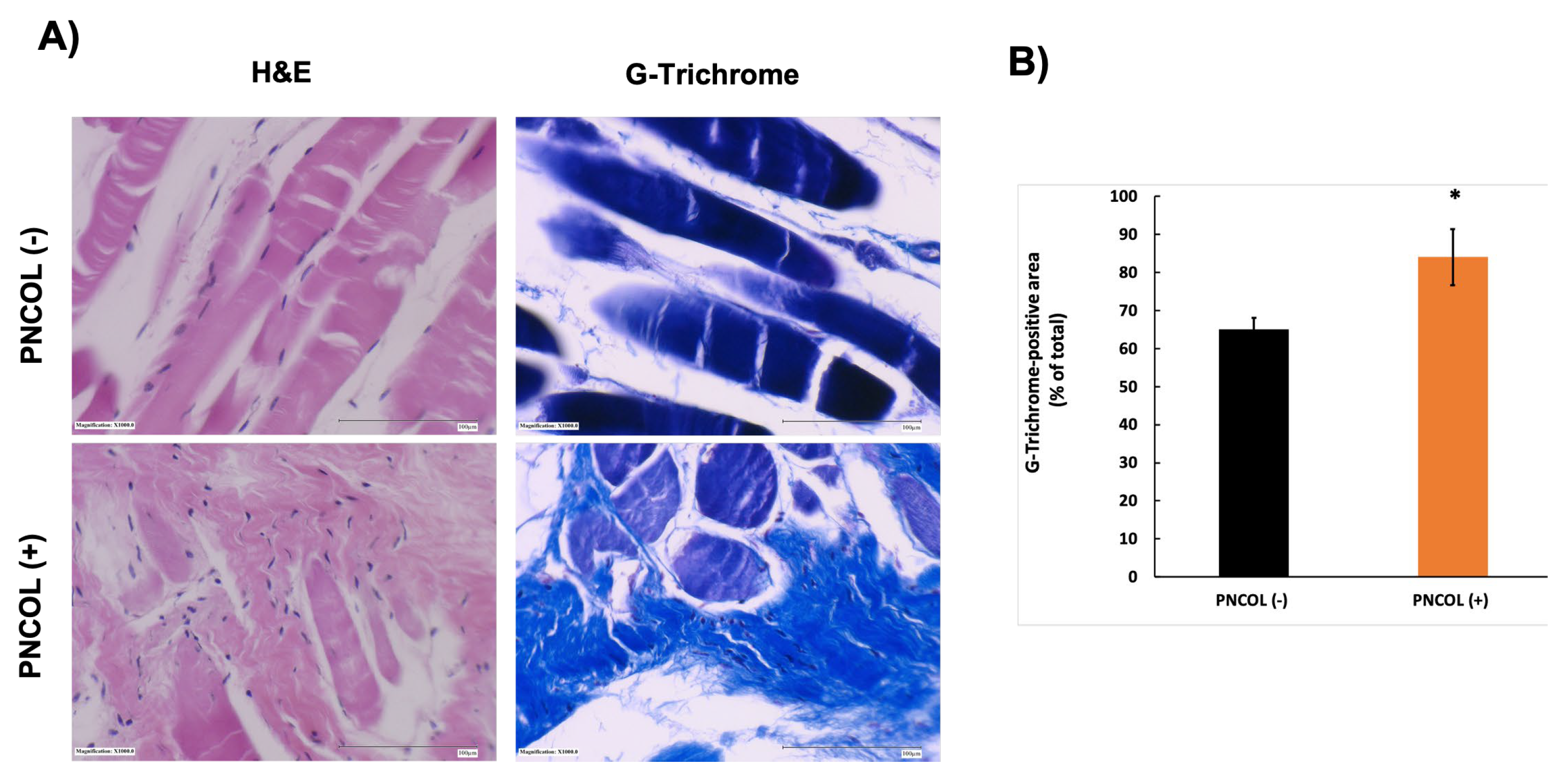

2.3. Structural and Morphological Stability of TA Muscle Defect Site After Treatments

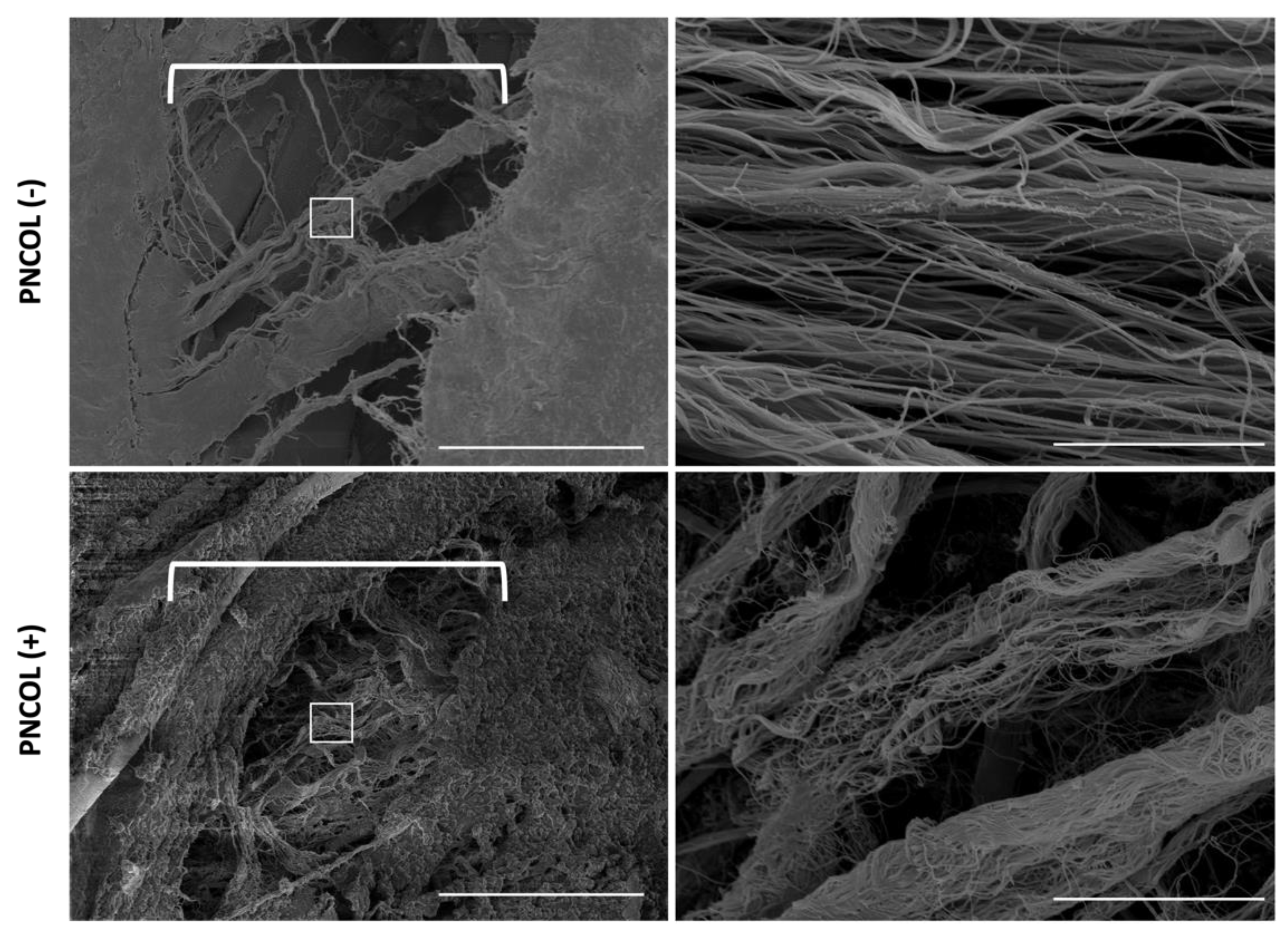

2.4. Matrix Organization and Muscle Fiber Alignment of TA Muscle Defect Site After Treatments

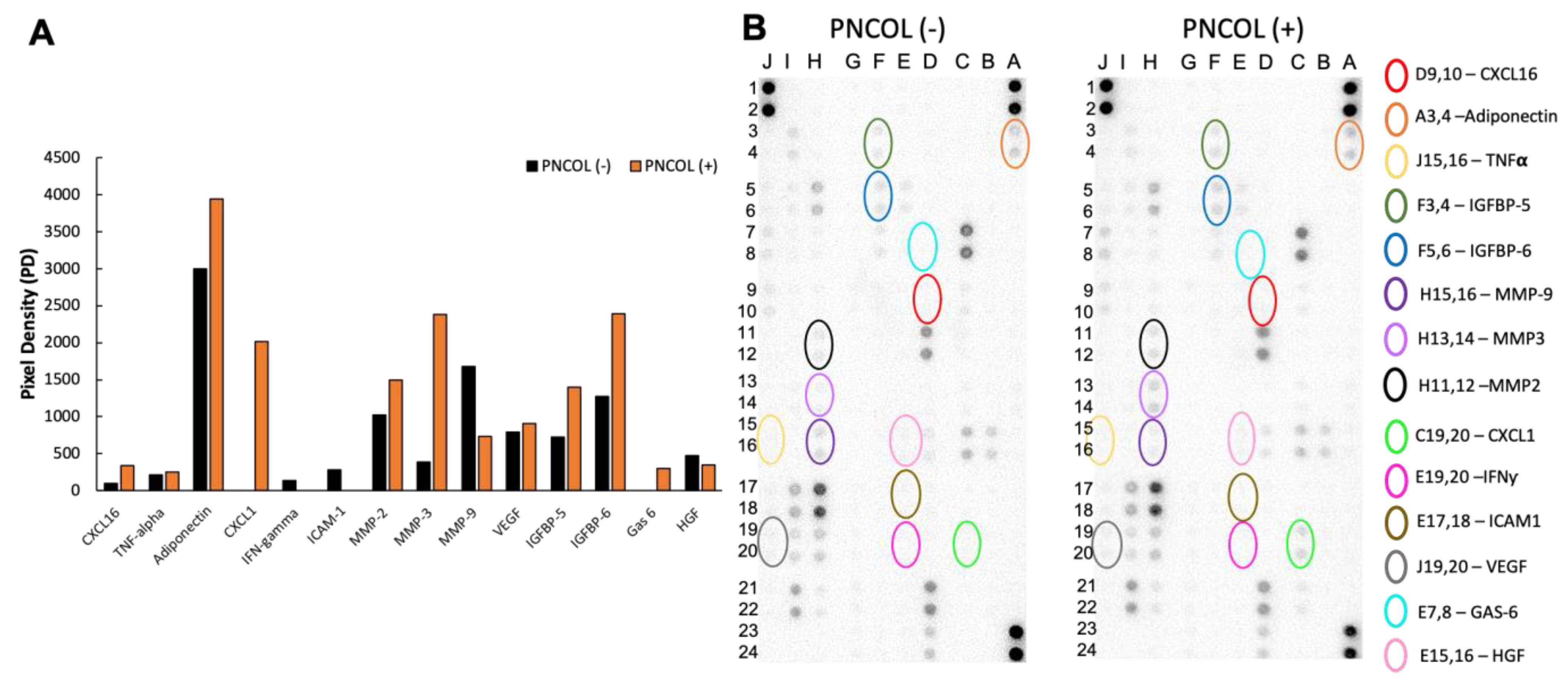

2.5. Cytokine and Chemokine Expression of Mouse Hindlimb Medium After Treatments

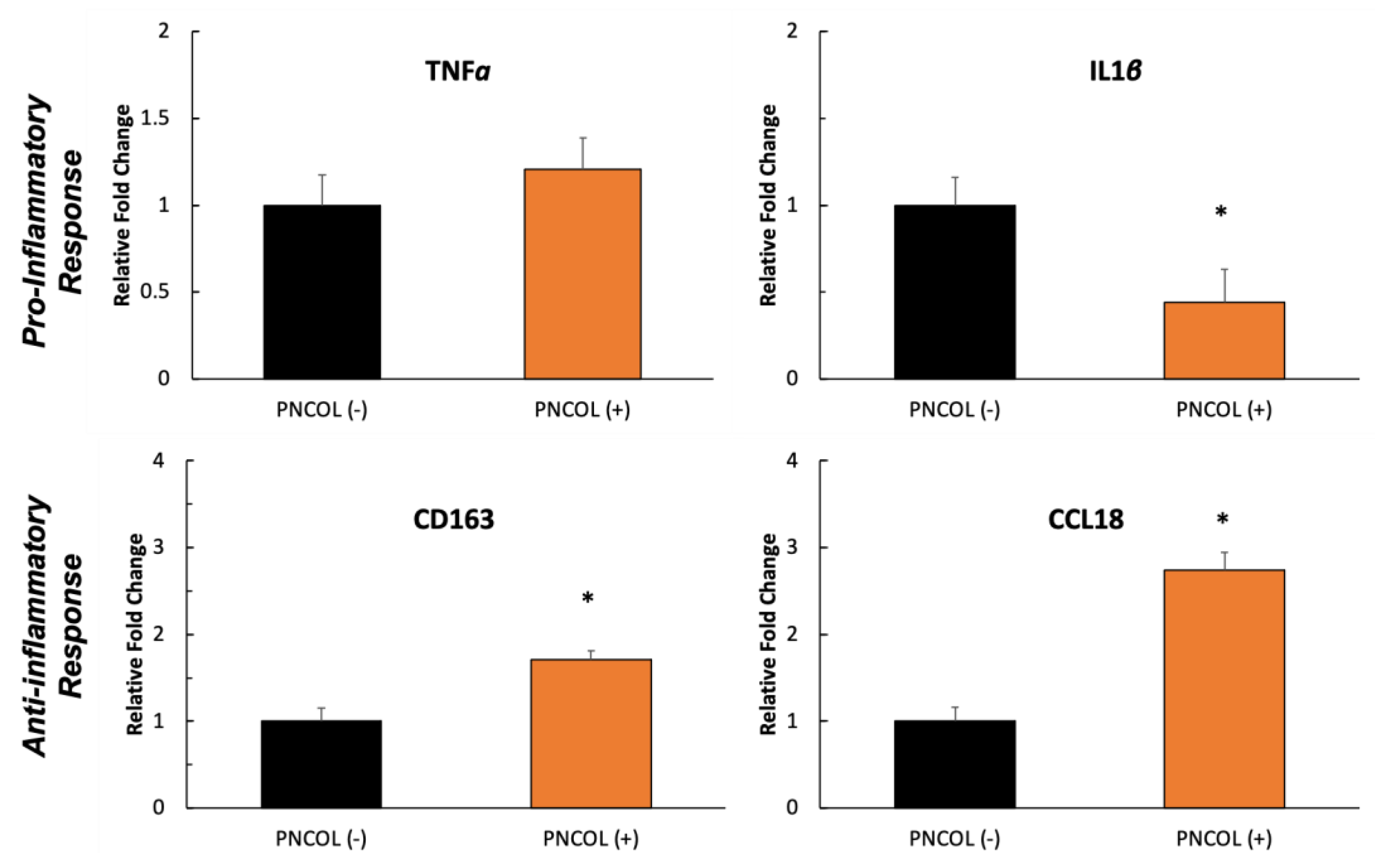

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis of TA Muscle Defect Site After Treatments

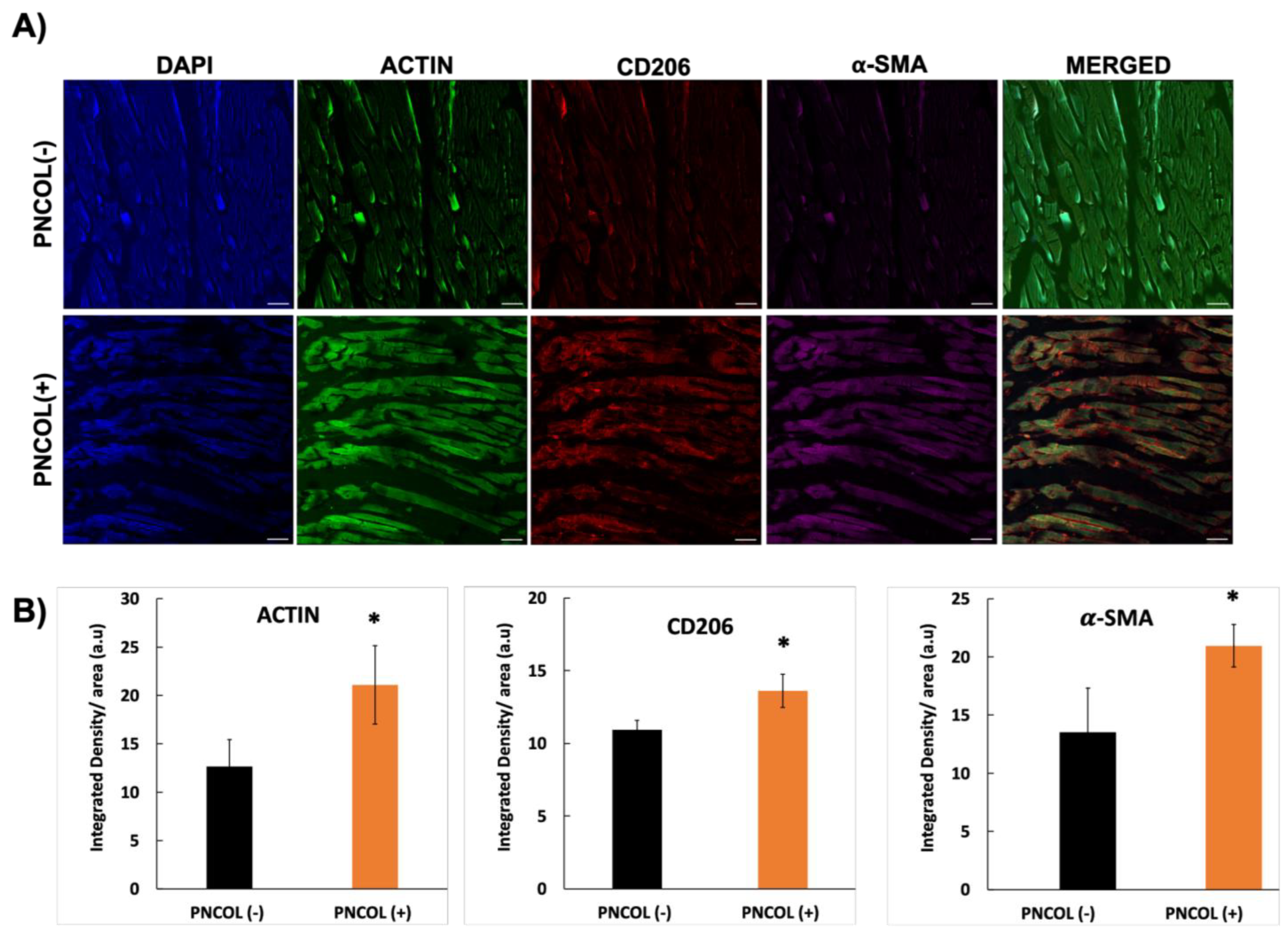

2.7. Inflammation Stability of TA Muscle Defect Site After Treatments

3. Discussion

4. Methods and Materials

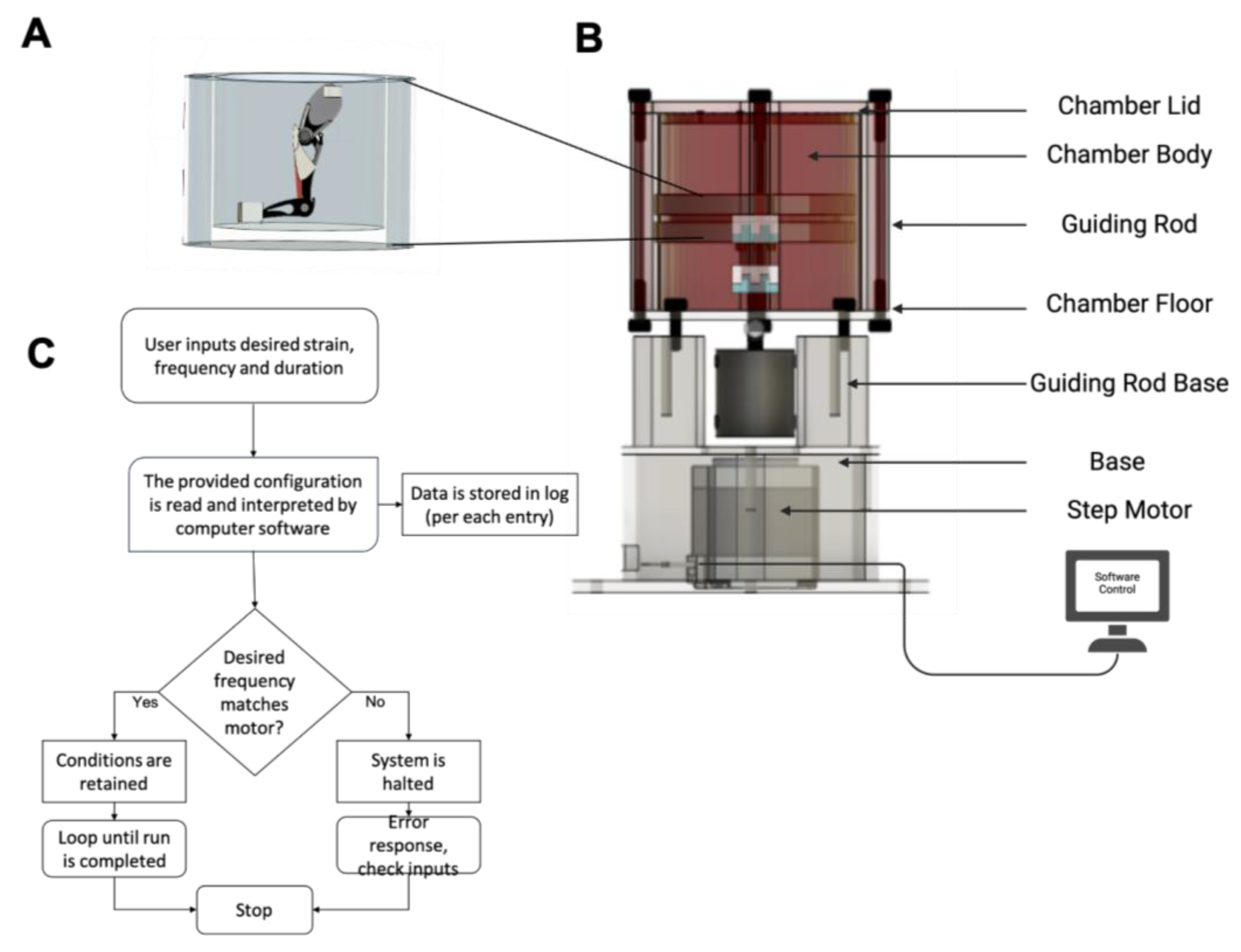

4.1. Ex Vivo Organ Culture Platform and Mouse Hindlimb Culturing Under Mechanical Loading

4.2. Micro-CT Analysis of Mouse Hindlimb After Ex Vivo Organ Culturing Under Mechanical Loading

4.3. Myoblast Cell-Laden Injectable Matrix Synthesis for TA Muscle Regeneration

4.3.1. Cell-Laden Injectable Nanofibrous Matrix for Tibialis Anterior Muscle Regeneration

4.3.2. TA Muscle Defect Creation and Cell-Laden Matrix Injection to the Defect Site

4.4. Assessing the Effect of Cell-Laden Injectable Matrix for TA Muscle Regeneration Following Ex Vivo Organ Culture Under Dynamic Mechanical Loading

4.4.1. Structural and Morphological Characterizations of the Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culturing Under Mechanical Loading

- (1)

- Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

- (2)

- Histological Analysis and Quantification of Histological Data

4.4.2. Biological Characterization of the Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culturing Under Mechanical Loading

- (1)

- Cell Viability Analysis

- (2)

- Proteome Array Analysis

- (3)

- Gene Expression Analysis

- (4)

- Immunostaining and Immunohistochemical Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCL-18 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-18 |

| CD163 | Cluster of Differentiation 163 |

| CD206 | Cluster of Differentiation 206 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL1β | Interleukin beta 1 |

| LPS | Lipid polysaccharide |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MRF4 | Myogenic regulatory factor 4 |

| MYF5 | Myogenic regulatory factor 5 |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PD | Pixel density |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PNCOL | Polycaprolactone nanofiber and collagen |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| C2C12 | Immortalized mouse myoblast cell line |

| List of Units and Symbols: | |

| M | Molar |

| U | Unit |

| v/v | Volume per volume |

| w/v | Weight per volume |

| μ | Micro |

References

- Lloyd, D. The future of in-field sports biomechanics: Wearables plus modelling compute real-time in vivo tissue loading to prevent and repair musculoskeletal injuries. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 1284–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, W.R.; Scott, A.; Loghmani, M.T.; Ward, S.R.; Warden, S.J. Understanding Mechanobiology: Physical Therapists as a Force in Mechanotherapy and Musculoskeletal Regenerative Rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, Z.; Yin, H.; Nerlich, M.; Pfeifer, C.G.; Docheva, D. Boosting tendon repair: Interplay of cells, growth factors and scaffold-free and gel-based carriers. J. Exp. Orthop. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Q.; Adam, N.C.; Hosseini Nasab, S.H.; Taylor, W.R.; Smith, C.R. Techniques for In Vivo Measurement of Ligament and Tendon Strain: A Review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.; Holfeld, J.; Schaden, W.; Orgill, D.; Ogawa, R. Mechanotherapy: Revisiting physical therapy and recruiting mechanobiology for a new era in medicine. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.M.; Kim, A.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Park, J.K.; Lee, M.M.; Hwang, M.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, K.S. Therapeutic effects of mouse adipose-derived stem cells and losartan in the skeletal muscle of injured mdx mice. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouly, V.; Aamiri, A.; Bigot, A.; Cooper, R.N.; Di Donna, S.; Furling, D.; Gidaro, T.; Jacquemin, V.; Mamchaoui, K.; Negroni, E.; et al. The mitotic clock in skeletal muscle regeneration, disease and cell mediated gene therapy. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2005, 184, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qazi, T.H.; Duda, G.N.; Ort, M.J.; Perka, C.; Geissler, S.; Winkler, T. Cell therapy to improve regeneration of skeletal muscle injuries. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Han, Y.; Guo, B. Injectable conductive micro-cryogel as a muscle stem cell carrier improves myogenic proliferation, differentiation and in situ skeletal muscle regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2022, 151, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesireddy, V. Evaluation of adipose-derived stem cells for tissue-engineered muscle repair construct-mediated repair of a murine model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anloague, A.; Mahoney, A.; Ogunbekun, O.; Hiland, T.A.; Thompson, W.R.; Larsen, B.; Loghmani, M.T.; Hum, J.M.; Lowery, J.W. Mechanical stimulation of human dermal fibroblasts regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines: Potential insight into soft tissue manual therapies. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wufuer, M.; Lee, G.; Hur, W.; Jeon, B.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, T.H.; Lee, S. Skin-on-a-chip model simulating inflammation, edema and drug-based treatment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schemitsch, E.H. Size Matters: Defining Critical in Bone Defect Size! J. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, S20–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayan, M.; Huang, N.F. Pre-Clinical Cell Therapeutic Approaches for Repair of Volumetric Muscle Loss. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bialorucki, C.; Subramanian, G.; Elsaadany, M.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. In situ osteoblast mineralization mediates post-injection mechanical properties of osteoconductive material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 38, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, N.J.N.; Arifin, N.; Noordin, K.; Yusop, N. Bone repair and key signalling pathways for cell-based bone regenerative therapy: A review. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ukeba, D.; Sudo, H.; Tsujimoto, T.; Ura, K.; Yamada, K.; Iwasaki, N. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells combined with ultra-purified alginate gel as a regenerative therapeutic strategy after discectomy for degenerated intervertebral discs. EBioMedicine 2020, 53, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fleming, J.W.; Capel, A.J.; Rimington, R.P.; Player, D.J.; Stolzing, A.; Lewis, M.P. Functional regeneration of tissue engineered skeletal muscle in vitro is dependent on the inclusion of basement membrane proteins. Cytoskeleton 2019, 76, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ragini, B.; Kandhasamy, S.; Jacob, J.P.; Vijayakumar, S. Synthesis and in vitro characteristics of biogenic-derived hydroxyapatite for bone remodeling applications. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharibshahian, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Kamalabadi Farahani, M.; Salehi, M. Fabrication of Rosuvastatin-Incorporated Polycaprolactone -Gelatin Scaffold for Bone Repair: A Preliminary In Vitro Study. Cell J. 2024, 26, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akhter, M.N.; Hara, E.S.; Kadoya, K.; Okada, M.; Matsumoto, T. Cellular Fragments as Biomaterial for Rapid In Vitro Bone-Like Tissue Synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lawrence, M.M.; Van Pelt, D.W.; Confides, A.L.; Hettinger, Z.R.; Hunt, E.R.; Reid, J.J.; Laurin, J.L.; Peelor, F.F.; Butterfield, T.A., 3rd; Miller, B.F.; et al. Muscle from aged rats is resistant to mechanotherapy during atrophy and reloading. Geroscience 2021, 43, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miokovic, T.; Armbrecht, G.; Gast, U.; Rawer, R.; Roth, H.J.; Runge, M.; Felsenberg, D.; Belavy, D.L. Muscle atrophy, pain, and damage in bed rest reduced by resistive (vibration) exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicari, B.M.; Agrawal, V.; Siu, B.F.; Medberry, C.J.; Dearth, C.L.; Turner, N.J.; Badylak, S.F. A murine model of volumetric muscle loss and a regenerative medicine approach for tissue replacement. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 1941–1948, Erratum in Tissue Eng. Part A 2018, 24, 861. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0475.correction. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tejedera-Villafranca, A.; Montolio, M.; Ramon-Azcon, J.; Fernandez-Costa, J.M. Mimicking sarcolemmal damagein vitro: A contractile 3D model of skeletal muscle for drug testing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 045024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacho, D.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Mechanome-Guided Strategies in Regenerative Rehabilitation. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 29, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, J.T.; Kasukonis, B.; Dunlap, G.; Perry, R.; Washington, T.; Wolchok, J.C. Regenerative Repair of Volumetric Muscle Loss Injury is Sensitive to Age. Tissue Eng. Part A 2020, 26, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hackmann, M.J.; Elliot, J.G.; Green, F.H.Y.; Cairncross, A.; Cense, B.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Langton, D.; James, A.L.; Noble, P.B.; Donovan, G.M. Requirements and limitations of imaging airway smooth muscle throughout the lung in vivo. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2022, 301, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werkhausen, A.; Gloersen, O.; Nordez, A.; Paulsen, G.; Bojsen-Moller, J.; Seynnes, O.R. Linking muscle architecture and function in vivo: Conceptual or methodological limitations? PeerJ 2023, 11, e15194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Timson, B.F. Evaluation of animal models for the study of exercise-induced muscle enlargement. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1990, 69, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, T. Animal models of muscular dystrophy--what can they teach us? Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1991, 17, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabei, M.; Lee, S.S.M.; Perreault, E.J.; Sandercock, T.G. Shear wave velocity is sensitive to changes in muscle stiffness that occur independently from changes in force. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2020, 128, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, L.R.; Meyer, G.A. Skeletal muscle explants: Ex-vivo models to study cellular behavior in a complex tissue environment. Connect. Tissue Res. 2020, 61, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naik, N.N.; Vadloori, B.; Poosala, S.; Srivastava, P.; Coecke, S.; Smith, A.; Akhtar, A.; Roper, C.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Bhyravbhatla, B.; et al. Advances in Animal Models and Cutting-Edge Research in Alternatives: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on 3Rs Research and Progress, Vishakhapatnam, 2022. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2023, 51, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur Clark, J. The 3Rs in research: A contemporary approach to replacement, reduction and refinement. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczesny, S.E. Ex vivo models of musculoskeletal tissues. Connect. Tissue Res. 2020, 61, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Silva, S.P.; Novicky, A.; Javaheri, B.; Rawlinson, S.C.F.; Pitsillides, A.A. Using Cell and Organ Culture Models to Analyze Responses of Bone Cells to Mechanical Stimulation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1914, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll, T.; Cole, S.; Madren-Whalley, J.; Booker, L.; Dorsey, R.; Li, A.; Salem, H. Generalized Additive Mixed-Models for Pharmacology Using Integrated Discrete Multiple Organ Co-Culture. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Secerovic, A.; Ristaniemi, A.; Cui, S.; Li, Z.; Soubrier, A.; Alini, M.; Ferguson, S.J.; Weder, G.; Heub, S.; Ledroit, D.; et al. Toward the Next Generation of Spine Bioreactors: Validation of an Ex Vivo Intervertebral Disc Organ Model and Customized Specimen Holder for Multiaxial Loading. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 3969–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Christiansen, B.A.; Bayly, P.V.; Silva, M.J. Constrained tibial vibration in mice: A method for studying the effects of vibrational loading of bone. J. Biomech. Eng. 2008, 130, 044502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, E.L.; Kanczler, J.M.; Oreffo, R.O. A new take on an old story: Chick limb organ culture for skeletal niche development and regenerative medicine evaluation. Eur. Cell Mater. 2013, 26, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viceconti, M.; Taddei, F.; Van Sint Jan, S.; Leardini, A.; Cristofolini, L.; Stea, S.; Baruffaldi, F.; Baleani, M. Multiscale modelling of the skeleton for the prediction of the risk of fracture. Clin. Biomech. 2008, 23, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, M.; Wark, A.W.; Day, S.; Buis, A. An ex vivo animal model to study the effect of transverse mechanical loading on skeletal muscle. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carriero, A.; Abela, L.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Shefelbine, S.J. Ex vivo determination of bone tissue strains for an in vivo mouse tibial loading model. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 2490–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Saito, T.; Nakamichi, R.; Yoshida, A.; Hiranaka, T.; Okazaki, Y.; Nezu, S.; Matsuhashi, M.; Shimamura, Y.; Furumatsu, T.; Nishida, K.; et al. The effect of mechanical stress on enthesis homeostasis in a rat Achilles enthesis organ culture model. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 40, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraldes, D.M.; Modenese, L.; Phillips, A.T. Consideration of multiple load cases is critical in modelling orthotropic bone adaptation in the femur. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2016, 15, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krzyszczyk, P.; Schloss, R.; Palmer, A.; Berthiaume, F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-wound Healing Phenotypes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Subramanian, G.; Bialorucki, C.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Nanofibrous yet injectable polycaprolactone-collagen bone tissue scaffold with osteoprogenitor cells and controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 51, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaadany, M.; Winters, K.; Adams, S.; Stasuk, A.; Ayan, H.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Equiaxial Strain Modulates Adipose-derived Stem Cell Differentiation within 3D Biphasic Scaffolds towards Annulus Fibrosus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roebke, E.; Jacho, D.; Eby, O.; Aldoohan, S.; Elsamaloty, H.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix for Treating Annulus Fibrosus Defects in Porcine Model: An Organ Culture Study. Life 2022, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kirk, B.; Duque, G. Muscle and Bone: An Indissoluble Union. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 1211–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Kamei, N.; Nakasa, T.; Adachi, N.; Deie, M.; Asahara, T.; Ochi, M. Acceleration of skeletal muscle regeneration in a rat skeletal muscle injury model by local injection of human peripheral blood-derived CD133-positive cells. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alheib, O.; da Silva, L.P.; da Silva Morais, A.; Mesquita, K.A.; Pirraco, R.P.; Reis, R.L.; Correlo, V.M. Injectable laminin-biofunctionalized gellan gum hydrogels loaded with myoblasts for skeletal muscle regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2022, 143, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kita, S.; Nishizawa, H.; Fukuda, S.; Fujishima, Y.; Obata, Y.; Nagao, H.; Masuda, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Adiponectin promotes muscle regeneration through binding to T-cadherin. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12219. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66545-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Filippo, K.; Dudeck, A.; Hasenberg, M.; Nye, E.; van Rooijen, N.; Hartmann, K.; Gunzer, M.; Roers, A.; Hogg, N. Mast cell and macrophage chemokines CXCL1/CXCL2 control the early stage of neutrophil recruitment during tissue inflammation. Blood 2013, 121, 4930–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ran, L.; Garcia, G.E.; Wang, X.H.; Han, S.; Du, J.; Mitch, W.E. Chemokine CXCL16 regulates neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into injured muscle, promoting muscle regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2518–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Conover, C.A. Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and bone metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 294, E10–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, A.V.; Humeres, C.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The role of alpha-smooth muscle actin in fibroblast-mediated matrix contraction and remodeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacho, D.; Rabino, A.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Mechanoresponsive regulation of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in three-dimensional tissue analogues: Mechanical strain amplitude dependency of fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shintaku, J.; Peterson, J.M.; Talbert, E.E.; Gu, J.M.; Ladner, K.J.; Williams, D.R.; Mousavi, K.; Wang, R.; Sartorelli, V.; Guttridge, D.C. MyoD Regulates Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Metabolism Cooperatively with Alternative NF-kappaB. Cell. Rep. 2016, 17, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- von Maltzahn, J.; Jones, A.E.; Parks, R.J.; Rudnicki, M.A. Pax7 is critical for the normal function of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16474–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller, B.F.; Hamilton, K.L.; Majeed, Z.R.; Abshire, S.M.; Confides, A.L.; Hayek, A.M.; Hunt, E.R.; Shipman, P.; Peelor, F.F.; Butterfield, T.A., 3rd; et al. Enhanced skeletal muscle regrowth and remodelling in massaged and contralateral non-massaged hindlimb. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moretti, I.; Ciciliot, S.; Dyar, K.A.; Abraham, R.; Murgia, M.; Agatea, L.; Akimoto, T.; Bicciato, S.; Forcato, M.; Pierre, P.; et al. MRF4 negatively regulates adult skeletal muscle growth by repressing MEF2 activity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Araujo Farias, V.; Carrillo-Galvez, A.B.; Martin, F.; Anderson, P. TGF-beta and mesenchymal stromal cells in regenerative medicine, autoimmunity and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2018, 43, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Thomsson, K.A.; Jin, C.; Ryberg, H.; Das, N.; Struglics, A.; Rolfson, O.; Bjorkman, L.I.; Eisler, T.; Schmidt, T.A.; et al. Truncated lubricin glycans in osteoarthritis stimulate the synoviocyte secretion of VEGFA, IL-8, and MIP-1alpha: Interplay between O-linked glycosylation and inflammatory cytokines. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 942406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bock, F.; Maruyama, K.; Regenfuss, B.; Hos, D.; Steven, P.; Heindl, L.M.; Cursiefen, C. Novel anti(lymph)angiogenic treatment strategies for corneal and ocular surface diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013, 34, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costamagna, D.; Duelen, R.; Penna, F.; Neumann, D.; Costelli, P.; Sampaolesi, M. Interleukin-4 administration improves muscle function, adult myogenesis, and lifespan of colon carcinoma-bearing mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jang, D.I.; Lee, A.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Song, H.R.; Park, J.H.; Kang, T.B.; Lee, S.R.; Yang, S.H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-alpha) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-alpha Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopez-Castejon, G.; Brough, D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1beta secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2011, 22, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Etzerodt, A.; Moestrup, S.K. CD163 and inflammation: Biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Casarosa, P.; Waldhoer, M.; LiWang, P.J.; Vischer, H.F.; Kledal, T.; Timmerman, H.; Schwartz, T.W.; Smit, M.J.; Leurs, R. CC and CX3C chemokines differentially interact with the N terminus of the human cytomegalovirus-encoded US28 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, R.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, L. Molecular mechanisms of exercise contributing to tissue regeneration. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Discher, D.E.; Janmey, P.; Wang, Y.L. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science 2005, 310, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, A.K.; Pheby, D.; Henehan, G.; Brown, R.; Sieving, P.; Sykora, P.; Marks, R.; Falsini, B.; Capodicasa, N.; Miertus, S.; et al. Ethical considerations regarding animal experimentation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E255–E266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kirk, R.G.W. Recovering The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique: The 3Rs and the Human Essence of Animal Research. Sci. Technol. Human Values 2018, 43, 622–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diaz, L.; Zambrano, E.; Flores, M.E.; Contreras, M.; Crispin, J.C.; Aleman, G.; Bravo, C.; Armenta, A.; Valdes, V.J.; Tovar, A.; et al. Ethical Considerations in Animal Research: The Principle of 3R’s. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2020, 73, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, P.; Drobek, C.; Budday, S.; Seitz, H. Simulating the mechanical stimulation of cells on a porous hydrogel scaffold using an FSI model to predict cell differentiation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1249867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pedaprolu, K.; Szczesny, S. A Novel, Open Source, Low-Cost Bioreactor for Load-Controlled Cyclic Loading of Tendon Explants. J. Biomech. Eng. 2022, 144, 084505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, G.; Elsaadany, M.; Bialorucki, C.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Creating homogenous strain distribution within 3D cell-encapsulated constructs using a simple and cost-effective uniaxial tensile bioreactor: Design and validation study. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1878–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaniamansour, P.; Jacho, D.; Teow, A.; Rabino, A.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Macrophage Mechano-Responsiveness Within Three-Dimensional Tissue Matrix upon Mechanotherapy-Associated Strains. Tissue Eng. Part A 2024, 30, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Subramanian, G.; Stasuk, A.; Elsaadany, M.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Effect of Uniaxial Tensile Cyclic Loading Regimes on Matrix Organization and Tenogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Encapsulated within 3D Collagen Scaffolds. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 6072406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nam, H.Y.; Balaji Raghavendran, H.R.; Pingguan-Murphy, B.; Abbas, A.A.; Merican, A.M.; Kamarul, T. Fate of tenogenic differentiation potential of human bone marrow stromal cells by uniaxial stretching affected by stretch-activated calcium channel agonist gadolinium. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rice, K.M.; Desai, D.H.; Preston, D.L.; Wehner, P.S.; Blough, E.R. Uniaxial stretch-induced regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, Akt and p70 S6 kinase in the ageing Fischer 344 x Brown Norway rat aorta. Exp. Physiol. 2007, 92, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornberger, T.A.; Armstrong, D.D.; Koh, T.J.; Burkholder, T.J.; Esser, K.A. Intracellular signaling specificity in response to uniaxial vs. multiaxial stretch: Implications for mechanotransduction. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005, 288, C185–C194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, J.W.; Farley, E.E.; O’Neil, T.K.; Burkholder, T.J.; Hornberger, T.A. Evidence that mechanosensors with distinct biomechanical properties allow for specificity in mechanotransduction. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Chan, A.H.P.; Jain, I.; Oropeza, B.P.; Zhou, T.; Nelsen, B.; Geisse, N.A.; Huang, N.F. Combinatorial extracellular matrix cues with mechanical strain induce differential effects on myogenesis in vitro. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 5893–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, S.J. Animal models for the study of tendinopathy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palmes, D.; Spiegel, H.U.; Schneider, T.O.; Langer, M.; Stratmann, U.; Budny, T.; Probst, A. Achilles tendon healing: Long-term biomechanical effects of postoperative mobilization and immobilization in a new mouse model. J. Orthop. Res. 2002, 20, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Peng, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, F.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z. Animal models of cancer metastasis to the bone. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1165380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baroi, S.; Czernik, P.J.; Chougule, A.; Griffin, P.R.; Lecka-Czernik, B. PPARG in osteocytes controls sclerostin expression, bone mass, marrow adiposity and mediates TZD-induced bone loss. Bone 2021, 147, 115913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bouxsein, M.L.; Boyd, S.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Guldberg, R.E.; Jepsen, K.J.; Muller, R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylan, N.; Bhat, S.; Ditto, M.; Lawrence, J.G.; Lecka-Czernik, B.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Polycaprolactone nanofiber interspersed collagen type-I scaffold for bone regeneration: A unique injectable osteogenic scaffold. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 8, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortridge, C.; Akbari Fakhrabadi, E.; Wuescher, L.M.; Worth, R.G.; Liberatore, M.W.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Impact of Digestive Inflammatory Environment and Genipin Crosslinking on Immunomodulatory Capacity of Injectable Musculoskeletal Tissue Scaffold. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gahlawat, S.; Oruc, D.; Paul, N.; Ragheb, M.; Patel, S.; Fasasi, O.; Sharma, P.; Shreiber, D.I.; Freeman, J.W. Tissue Engineered 3D Constructs for Volumetric Muscle Loss. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 2325–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cai, C.W.; Grey, J.A.; Hubmacher, D.; Han, W.M. Biomaterial-Based Regenerative Strategies for Volumetric Muscle Loss: Challenges and Solutions. Adv. Wound Care 2025, 14, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Su, E.Y.; Kennedy, C.S.; Vega-Soto, E.E.; Pallas, B.D.; Lukpat, S.N.; Hwang, D.H.; Bosek, D.W.; Forester, C.E.; Loebel, C.; Larkin, L.M. Repairing Volumetric Muscle Loss with Commercially Available Hydrogels in an Ovine Model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2024, 30, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Corona, B.T.; Chen, X.; Walters, T.J. A Standardized Rat Model of Volumetric Muscle Loss Injury for the Development of Tissue Engineering Therapies. BioResearch Open Access 2012, 1, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castor-Macias, J.A.; Larouche, J.A.; Wallace, E.C.; Spence, B.D.; Eames, A.; Yang, B.A.; Davis, C.; Brooks, S.V.; Maddipati, K.R.; Markworth, J.F.; et al. Maresin 1 Repletion Improves Muscle Regeneration After Volumetric Muscle Loss. bioRxiv 2022. bioRxiv:2022.11.19.517113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Xie, L.; Xiao, W.; Shi, B.; Li, J. A critical size volumetric muscle loss model in mouse masseter with impaired mastication on nutrition. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Howell, K.L.; Kaji, D.A.; Li, T.M.; Montero, A.; Yeoh, K.; Nasser, P.; Huang, A.H. Macrophage depletion impairs neonatal tendon regeneration. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRF4 | 5′-GCAAGACCTGCAAGAGAAC-3′ | 5′-GCGAAAGGAGGAGGCTTAA-3′ | [60] |

| MYF5 | 5′-CCGTGTTTCCCATGGTTGTG-3′ | 5′-GAGCACTCGGCTAATCGAAC-3′ | [60] |

| PAX7 | 5′-CAGCCAACTGTGATCCTGCT-3′ | 5′-CTTCATATGCGGCATCCACG-3′ | [60] |

| αSMA | 5′-GTCAGCACTTCGCATCAAGG-3′ | 5′-TTCACAGGATTCTGGGAGCGG-3′ | [58] |

| MYOD | 5′-GCAGGTGTAACCGTAACC-3′ | 5′-ACGTACAAATTCCCTGTAGC-3′ | [60] |

| MYOGENIN | 5′-GCCACAGATGCCACTACTTC-3′ | 5′-CAACTTCAGCACAGGAGACC-3′ | [60] |

| TGFβ1 | 5′-GGTTATCTTTTGATGTCACCG-3′ | 5′-GTTATGCTGGTTGTACAGGG-3′ | [100] |

| VEGF | 5′-GGTGCATTGGAGCCTTGCCT-3′ | 5′-TGGTGAGGTTTGATCCGCAT-3′ | [100] |

| CD163 | 5′-TCTGTTGGCCATTTTCGTCG-3′ | 5′-TGGTGGACTAAGTTCTCTCCTCTTGA-3′ | [100] |

| CCL18 | 5′-AAGAGCTCTGCTGCCTCGTCTA-3′ | 5′-CCCTCAGGCATTCAGCTTAC-3′ | [100] |

| TNFα | 5′-AGAGGGAAGAGTTCCCCAGGGAC-3′ | 5′-TGAGTCGGTCACCCTTCTCCAG-3′ | [100] |

| IL1β | 5′-CCAGCTACGAATCTCGGACCACC-3′ | 5′-AGCAATGGTAAACCAGTAGTTGG-3′ | [100] |

| GAPDH | 5′-GGCATTGGTCTCAATGACAA-3′ | 5′-TGTGAGGGAGATGCTCAGTC-3′ | [100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacho, D.; Huynh, J.; Crowe, E.; Rabino, A.; Yıldırım, M.; Czernik, P.J.; Lecka-Czernik, B.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Yildirim-Ayan, E. Critical-Size Muscle Defect Regeneration Using an Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix: An Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culture Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412120

Jacho D, Huynh J, Crowe E, Rabino A, Yıldırım M, Czernik PJ, Lecka-Czernik B, Garcia-Mata R, Yildirim-Ayan E. Critical-Size Muscle Defect Regeneration Using an Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix: An Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culture Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412120

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacho, Diego, James Huynh, Emily Crowe, Agustin Rabino, Mine Yıldırım, Piotr J. Czernik, Beata Lecka-Czernik, Rafael Garcia-Mata, and Eda Yildirim-Ayan. 2025. "Critical-Size Muscle Defect Regeneration Using an Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix: An Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culture Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412120

APA StyleJacho, D., Huynh, J., Crowe, E., Rabino, A., Yıldırım, M., Czernik, P. J., Lecka-Czernik, B., Garcia-Mata, R., & Yildirim-Ayan, E. (2025). Critical-Size Muscle Defect Regeneration Using an Injectable Cell-Laden Nanofibrous Matrix: An Ex Vivo Mouse Hindlimb Organ Culture Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412120