1. Introduction

Lipid peroxidation is a free-radical chain reaction in which lipids containing unsaturated fatty acids react with molecular oxygen to form lipid peroxides. The biological significance of this process is immense. Fatty acid hydroperoxides serve as precursors for various animal and plant hormones, including prostaglandins, leukotrienes, jasmonic acid, and their derivatives [

1]. However, uncontrolled lipid peroxidation leads to membrane damage, accumulation of toxic products, and ultimately cell death [

2].

Recently, ferroptosis—a new form of programmed cell death characterized by iron-dependent membrane destruction via lipid peroxidation—was discovered [

3]. Elevated lipid peroxidation levels are observed in multiple major diseases, such as myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, ischemic injury, inflammation, neurodegeneration, and cancer [

3]. Consequently, lipid peroxidation remains a central focus of modern biochemical and biomedical research.

Traditionally, lipid peroxidation levels are assessed using fluorescent probes that react with its specific products, including:

Probes for lipid hydroperoxides (e.g., LiperFluo [

4]);

Probes for lipid radicals (e.g., α-parinaric acid [

5], C11-BODIPY [

6], and NBD-Pen [

7]).

However, many of these probes exhibit cytotoxicity, limiting their use for real-time monitoring or in vivo imaging [

8].

Bioluminescent systems offer a powerful alternative, combining high sensitivity, minimal background, and compatibility with live imaging. To date, around ten distinct luciferase-luciferin systems have been characterized, forming the basis for diverse biosensing and imaging applications [

9], including in vivo visualization in laboratory animals [

10].

We previously showed that

Chaetopterus luciferase luminescence requires conjugated peroxides of polyunsaturated fatty acids and Fe

2+ ions [

11]. Here, we explore its potential as a bioluminescent reporter for real-time monitoring of lipid peroxidation.

2. Results

Our earlier work demonstrated that

Chaetopterus luciferase requires conjugated polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) peroxides and Fe

2+ ions for luminescence [

11,

12]. However, the precise role of these components remained unclear. Since fatty acid peroxides readily decompose in the presence of Fe

2+, forming radical intermediates and secondary products [

13,

14], we hypothesized that Fe

2+ could (1) act as a cofactor of luciferase, or (2) catalyze peroxide decomposition, generating the true substrates for the enzyme. To test this, we examined whether cytochrome C (Cyt C)—a heme-containing redox protein—could substitute Fe

2+. Cyt C catalyzed luminescence with efficiency comparable to Fe

2+ at equivalent concentrations (

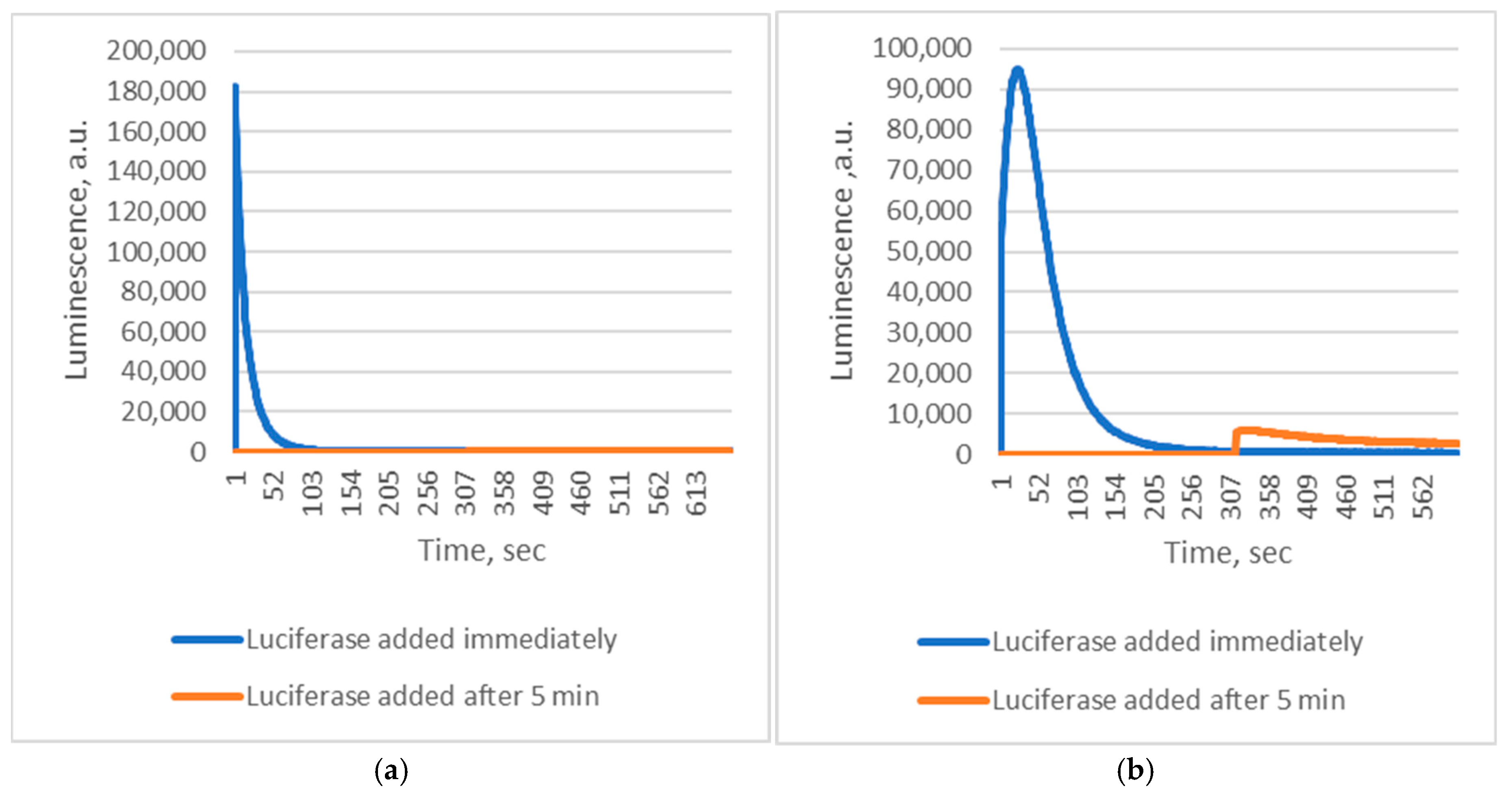

Figure 1). Importantly, the Fe

2+ chelator phenanthroline, which completely inhibits iron-driven luminescence (unpublished data), did not affect the Cyt C-mediated reaction.

These findings indicate that

Chaetopterus luciferase does not require Fe

2+ as a cofactor. Instead, luminescence results from the enzyme’s interaction with short-lived products generated during Fe

2+-catalyzed decomposition of conjugated fatty acid peroxides. Reactive alkoxyl radicals are known to form during Fe

2+-induced decomposition of fatty acid peroxides [

14]. However, this non-enzymatic process produces a complex and poorly defined mixture of reactive species, complicating mechanistic studies. In contrast, enzymatic oxidation of PUFAs by lipoxygenases generates alkoxyl radicals and derivatives in a more controlled manner [

15]. We therefore hypothesized that lipoxygenase-mediated oxidation of PUFAs could also yield substrates for

Chaetopterus luciferase. Supporting this idea, we observed that soybean lipoxygenase (LOX)-mediated peroxidation of linoleic acid produced luminescence comparable in intensity to that obtained with pre-formed linoleic acid peroxide and Fe

2+ (

Figure 1), though with distinct kinetics. Phenanthroline did not inhibit the LOX-driven reaction, suggesting that enzymatically generated intermediates directly induce luminescence. When oxidation of linoleic acid (via LOX) or decomposition of its peroxide (via Fe

2+) was initiated before adding luciferase, luminescence was at least 10 times weaker if the enzyme addition was delayed by five minutes (

Figure 2). This confirms the extreme instability of the luminescent intermediates.

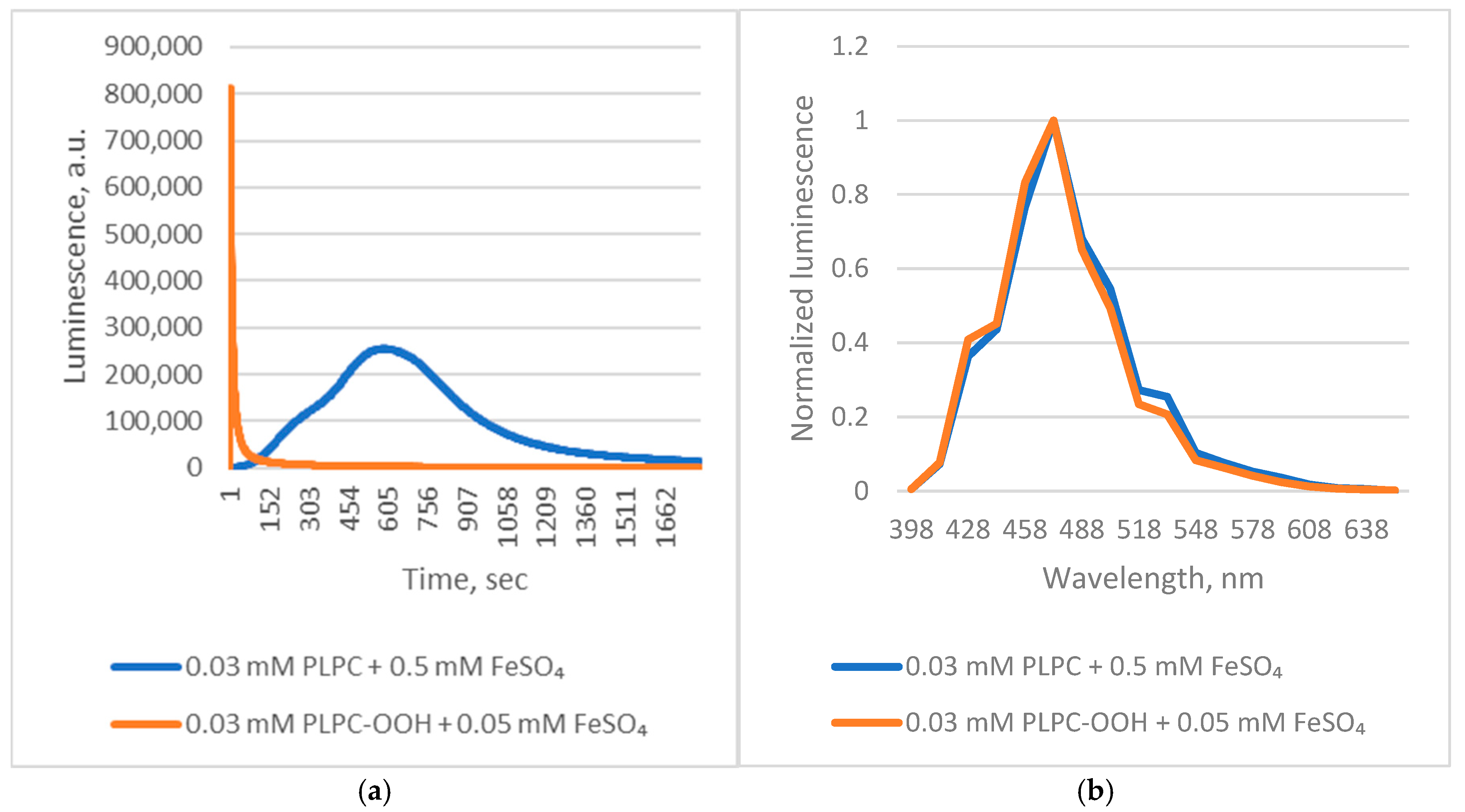

Applying these insights, we examined

Chaetopterus luciferase luminescence during Fe

2+-induced peroxidation of native 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC). The reaction triggered strong luminescence with kinetic characteristics typical of autocatalytic lipid peroxidation, including a lag phase (

Figure 3).

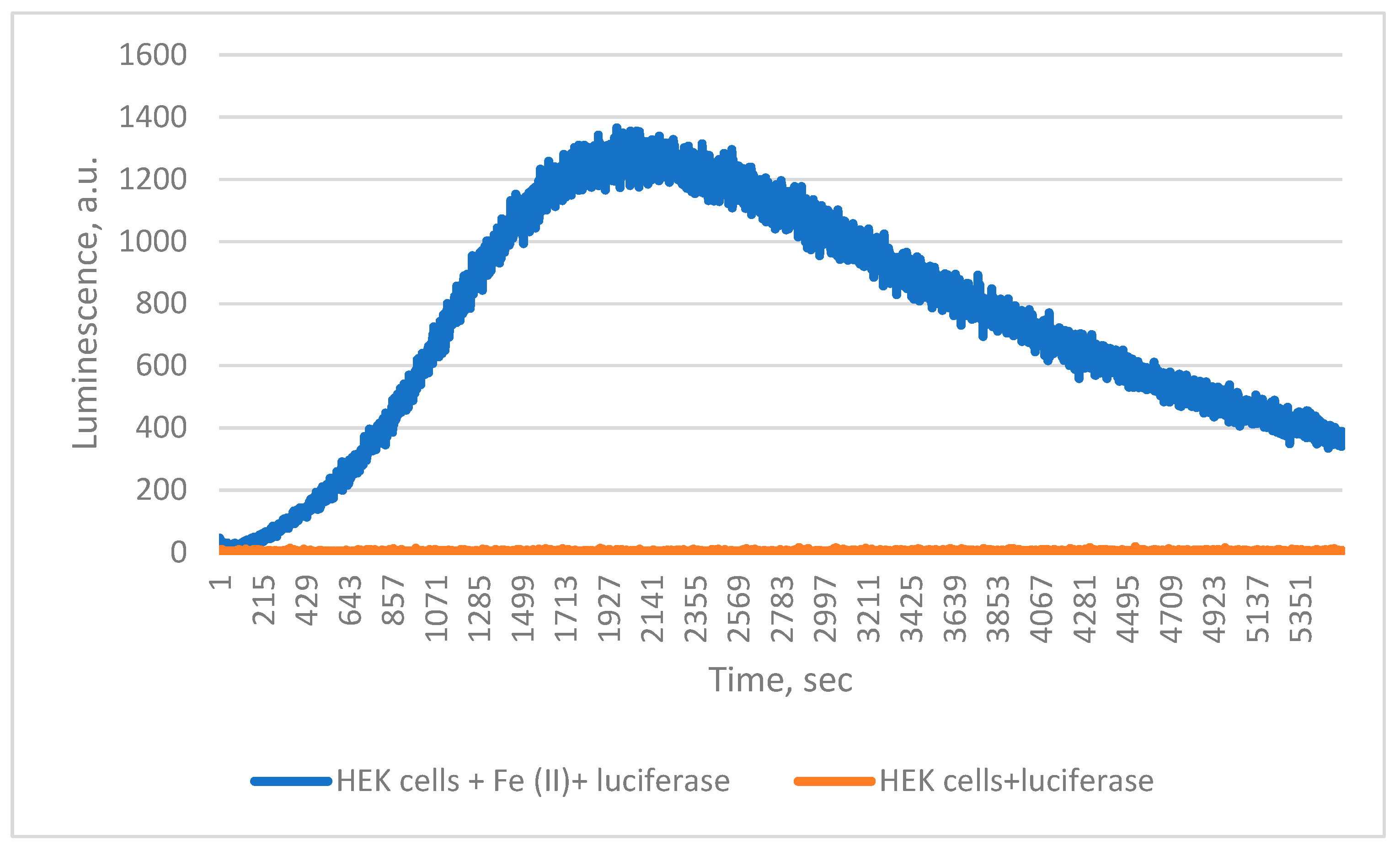

Finally, when ferroptosis was simulated in HEK 293 T cells by Fe

2+ treatment in the presence of

Chaetopterus luciferase, luminescence increased steadily, unlike in untreated controls (

Figure 4). During incubation, cell death approximately doubled, from 6% to 13%.

3. Discussion

Visualization of intracellular processes in live organisms remains a key scientific challenge. Several classes of probes are used for this purpose:

Small molecules, often fluorescent, that bind specific structures or respond to environmental changes [

16];

Fluorescent proteins, including fusion constructs and engineered sensors [

17];

Bioluminescent systems, and synthetic sensors derived from them [

18].

Small-molecule probes are primarily limited to cell culture due to high cost, poor penetration, and degradation. Fluorescent proteins overcome many of these limitations but may oligomerize and suffer from tissue autofluorescence interference.

Bioluminescent systems, in contrast, exhibit negligible background. Their main limitation is the need for luciferin supplementation. Recently, autonomous bioluminescent systems that function without external luciferin have gained attention [

19].

Currently, only small-molecule sensors are available for detecting lipid peroxidation, highlighting the need for a genetically encodable alternative. Our results demonstrate that Chaetopterus luciferase utilizes short-lived byproducts of lipid peroxidation as substrates, making it a natural, genetically encoded bioluminescent sensor for lipid peroxidation that requires no exogenous luciferin.

It is known that active alkoxyl and peroxyl radicals are formed during chemical or enzymatic lipid peroxidation. Peroxyl radicals formed during Fe

3+-mediated PUFAs-peroxide decomposition do not trigger

Chaetopterus luminescence [

12], suggesting that alkoxyl radicals or their derivatives serve as the actual substrates.

During ferroptosis, iron-dependent lipid peroxidation causes membrane destruction [

3]. Our results show that

Chaetopterus luciferase can detect such membrane damage, underscoring its potential as a tool for real-time monitoring of ferroptosis and oxidative stress.

4. Materials and Methods

Reagents. 1-Palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Linoleic acid was purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Soybean lipoxygenase (Type I-B, ≥50,000 U/mg) and all other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise specified. 1-Palmitoyl-2-hydroperoxyoctadecadienoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC-OOH) and (9Z,11E)-13-hydroperoxyoctadeca-9,11-dienoic acid (13-HPODE) were synthesized as described previously [

11].

Chaetopterus luciferase was purified from natural sources (see

Supplementary Material).

Biochemical assays. Reaction mixtures (100 µL) contained phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), luciferase (1 µg, 1 µL of 1 mg/mL stock), and 3 mM methanolic substrate solution (1 µL). Initiators of peroxidation were added as follows: FeSO4 (0.1 mM, 1 µL) or cytochrome C (0.1 mM, 1 µL) for linoleic acid peroxide assays; soybean lipoxygenase (0.5 mg/mL, 1 µL) for linoleic acid; and FeSO4 (50 mM or 5 mM, 1 µL) for PLPC and PLPC-OOH assays, respectively. Where indicated, 1,10-phenanthroline was used at a final concentration of 0.1 mM. Luminescence was recorded immediately after mixing at room temperature.

Cell-based assays. HEK 293 T cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 10% FBS (PanEko, Moscow, Russia) to monolayer confluence, detached with trypsin/versene, centrifuged (900 g, 5 min), and resuspended in PBS. Cell concentration and viability were determined using trypan blue and a Luna cell counter (Logos Biosystems, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). Reaction mixtures contained 50 µL PBS, 1 µL of 1 mg/mL luciferase, 1 µL of 50 mM FeSO4, and 5 × 105 cells in 100 µL PBS. Luciferase was pre-incubated with FeSO4 for 2 min before cell addition. Luminescence was measured immediately at room temperature.

Instrumentation. Bioluminescence kinetics were recorded using a BLM-530 luminometer (Oberon-K, Krasnoyarsk, Russia) equipped with a Hamamatsu H12056P-110 photomultiplier (HAMAMATSU PHOTONICS K.K., Hamamatsu City, Japan) [

20]. Bioluminescence spectrums were recorded using microplate reader Spark (Tecan, Grödig, Austria).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.S. and A.S.T.; methodology, A.S.S.; validation, A.S.S.; investigation, A.S.S., R.I.Z. and K.V.P.; resources, V.B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.S.; writing—review and editing, R.I.Z. and I.V.Y.; visualization, A.S.S.; supervision, A.S.S.; project administration, I.V.Y.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education, grant number 075-15-2024-681.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cyt C | Cytochrome C |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| HEK | Human Embryonic Kidney |

| 13-HPODE | (9Z,11E)-13-hydroperoxyoctadecaenoic acid |

| LOX | soybean lipoxygenase, lipoxidase from Glycine max |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 |

| PLPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| PLPC-OOH | 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroperoxyoctadecadienoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

References

- Samuelsson, B. From studies of biochemical mechanism to novel biological mediators: Prostaglandin endoperoxides, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. Biosci. Rep. 1983, 3, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaschler, M.M.; Stockwell, B.R. Lipid peroxidation in cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Saito, Y.; Sakiyama, J.; Ohuchi, Y.; Oseto, F.; Noguchi, N. A novel fluorescent probe with high sensitivity and selective detection of lipid hydroperoxides in cells. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 7894–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, L.A.; Hudson, B.S.; Simoni, R.D. Conjugated polyene fatty acids as membrane probes: Preliminary characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 1649–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummen, G.P.; van Liebergen, L.C.; Op den Kamp, J.A.; Post, J.A. C11-BODIPY(581/591), an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent lipid peroxidation probe: (micro)spectroscopic characterization and validation of methodology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Bamba, T.; Yamada, K.I. Method for Structural Determination of Lipid-Derived Radicals. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 6993–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Nijiati, S.; Tang, L.; Ye, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X. Ferroptosis Detection: From Approaches to Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202300379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlobay, A.A.; Kaskova, Z.M.; Yampolsky, I.V. Palette of Luciferases: Natural Biotools for New Applications in Biomedicine. Acta Naturae 2020, 12, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiszka, K.A.; Dullin, C.; Steffens, H.; Koenen, T.; Rothermel, E.; Alves, F.; Gregor, C. Autonomous bioluminescence emission from transgenic mice. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads0463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagitova, R.I.; Purtov, K.V.; Shcheglov, A.S.; Mineev, K.S.; Dubinnyi, M.A.; Myasnyanko, I.N.; Belozerova, O.A.; Pakhomova, V.G.; Petushkov, V.N.; Rodionova, N.S.; et al. Conjugated Dienoic Acid Peroxides as Substrates in Chaetopterus Bioluminescence System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purtov, K.V.; Petushkov, V.N.; Rodionova, N.S.; Pakhomova, V.G.; Myasnyanko, I.N.; Myshkina, N.M.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Gitelson, J.I. Luciferin-Luciferase System of Marine Polychaete Chaetopterus variopedatus. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 486, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, E.; Laguerre, M.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Lecomte, J.; Villeneuve, P. Navigating the complexity of lipid oxidation and antioxidation: A review of evaluation methods and emerging approaches. Prog. Lipid Res. 2025, 97, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, H.W. Oxygen radical chemistry of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1989, 7, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, S.Y.; Yue, G.H.; Tomer, K.B.; Mason, R.P. Identification of all classes of spin-trapped carbon-centered radicals in soybean lipoxygenase-dependent lipid peroxidations of omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids via LC/ESR, LC/MS, and tandem MS. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udhayakumari, D.; Ramasundaram, S.; Jerome, P.; Oh, T.H. A Review on Small Molecule Based Fluorescence Chemosensors for Bioimaging Applications. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 3763–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki, A.; Niino, Y. Molecular spies for bioimaging-fluorescent protein-based probes. Mol. Cell. 2015, 58, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Liang, G. Inspired by nature: Bioluminescent systems for bioimaging applications. Talanta 2025, 281, 126821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, S.H.; Kakizuka, T.; Hattori, M.; Nagai, T. Autonomous multicolor bioluminescence imaging in bacteria, mammalian, and plant hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2406358121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.hamamatsu.com/eu/en/product/optical-sensors/pmt/pmt-module/current-output-type/H12056P-110.html (accessed on 5 December 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).