Integrating Multi-Source Directed Gene Networks and Multi-Omics Data to Identify Cancer Driver Genes Based on Graph Neural Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baselines

2.2. Hyperparameters and Experimental Environment

2.3. Performance on Pan-Cancer Driver Gene Prediction

2.4. Ablation Experiments

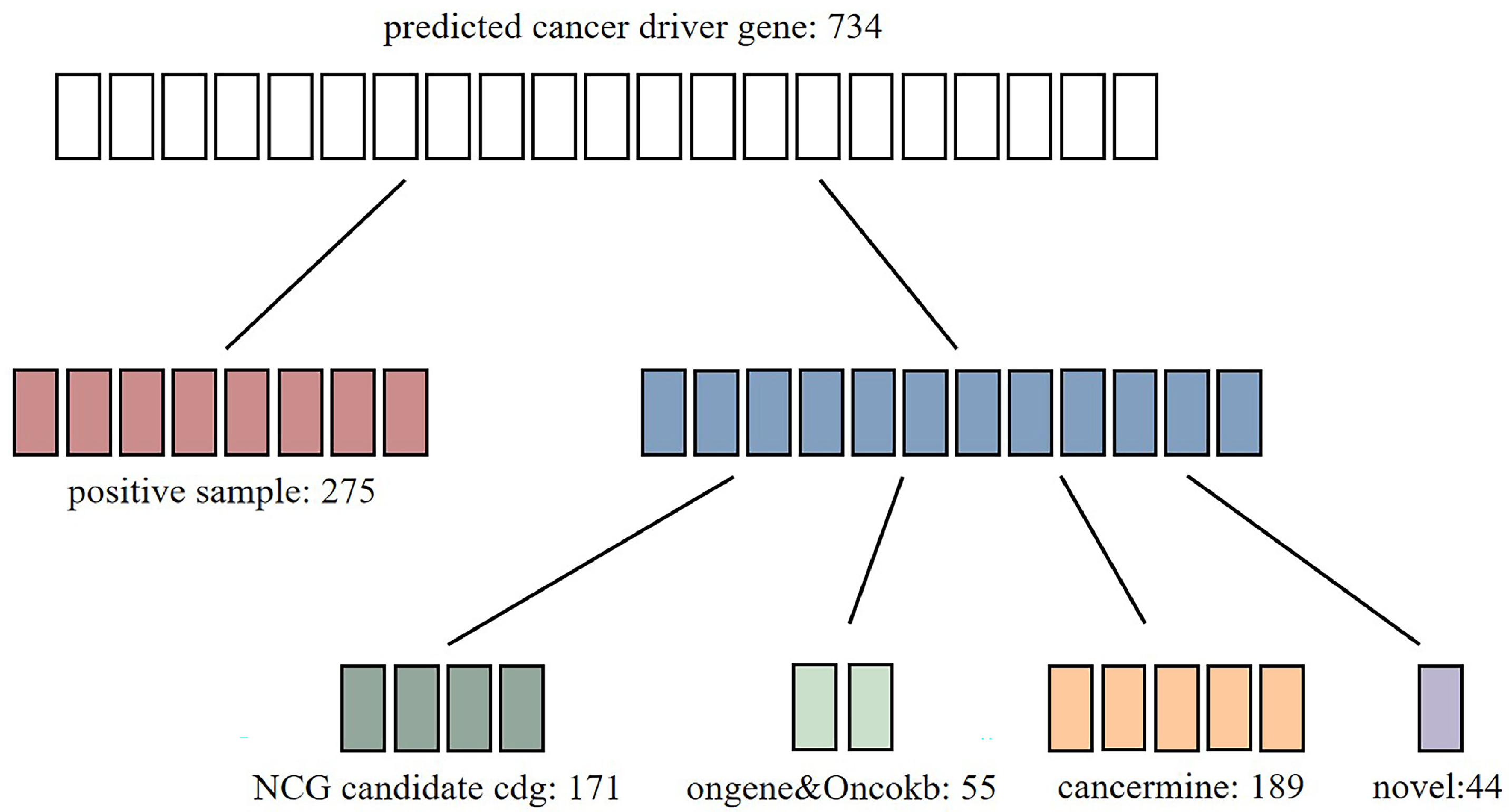

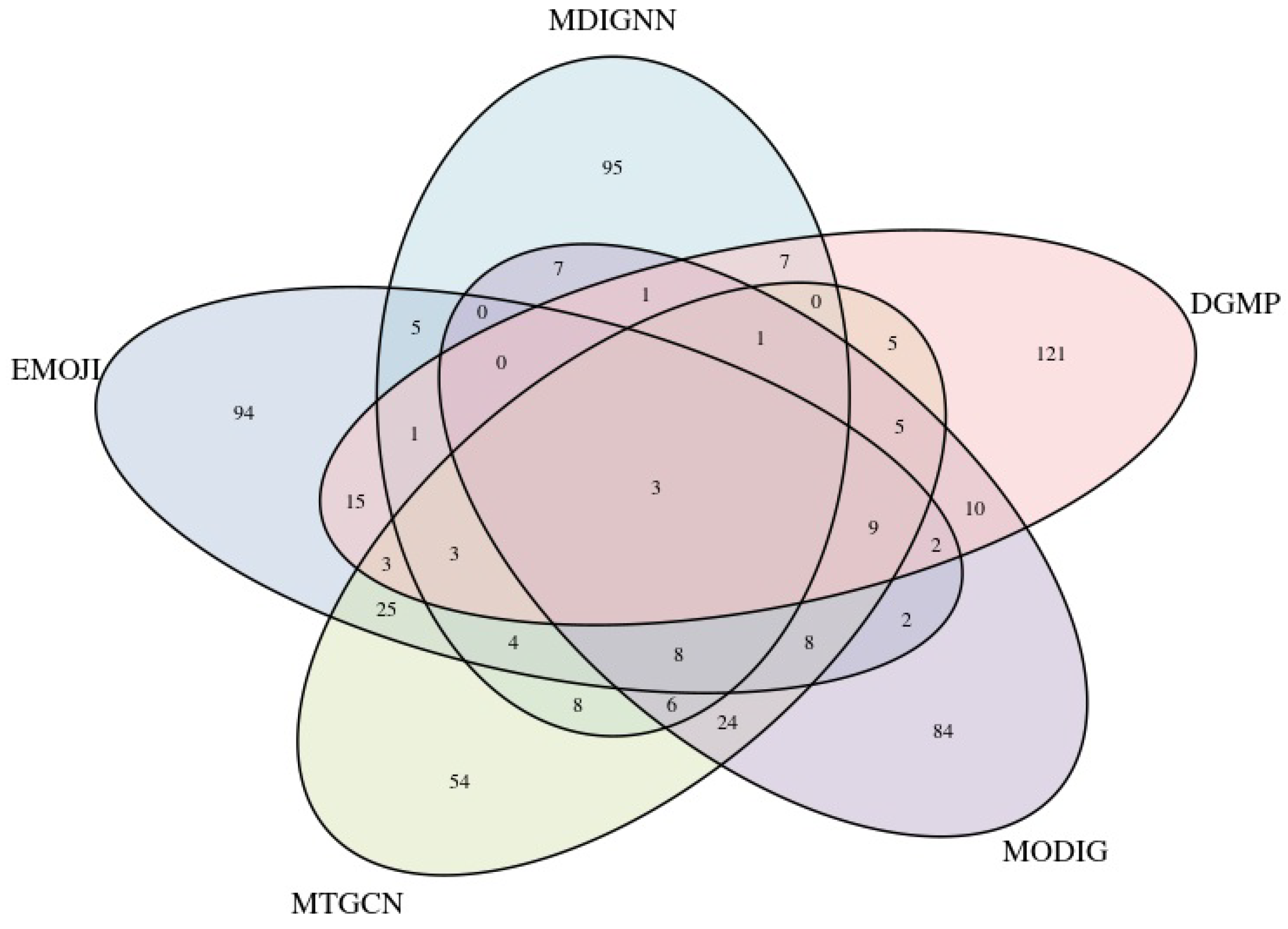

2.5. Performance on Identifying Novel Cancer Genes

2.6. Analysis of Novel Cancer Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Datasets

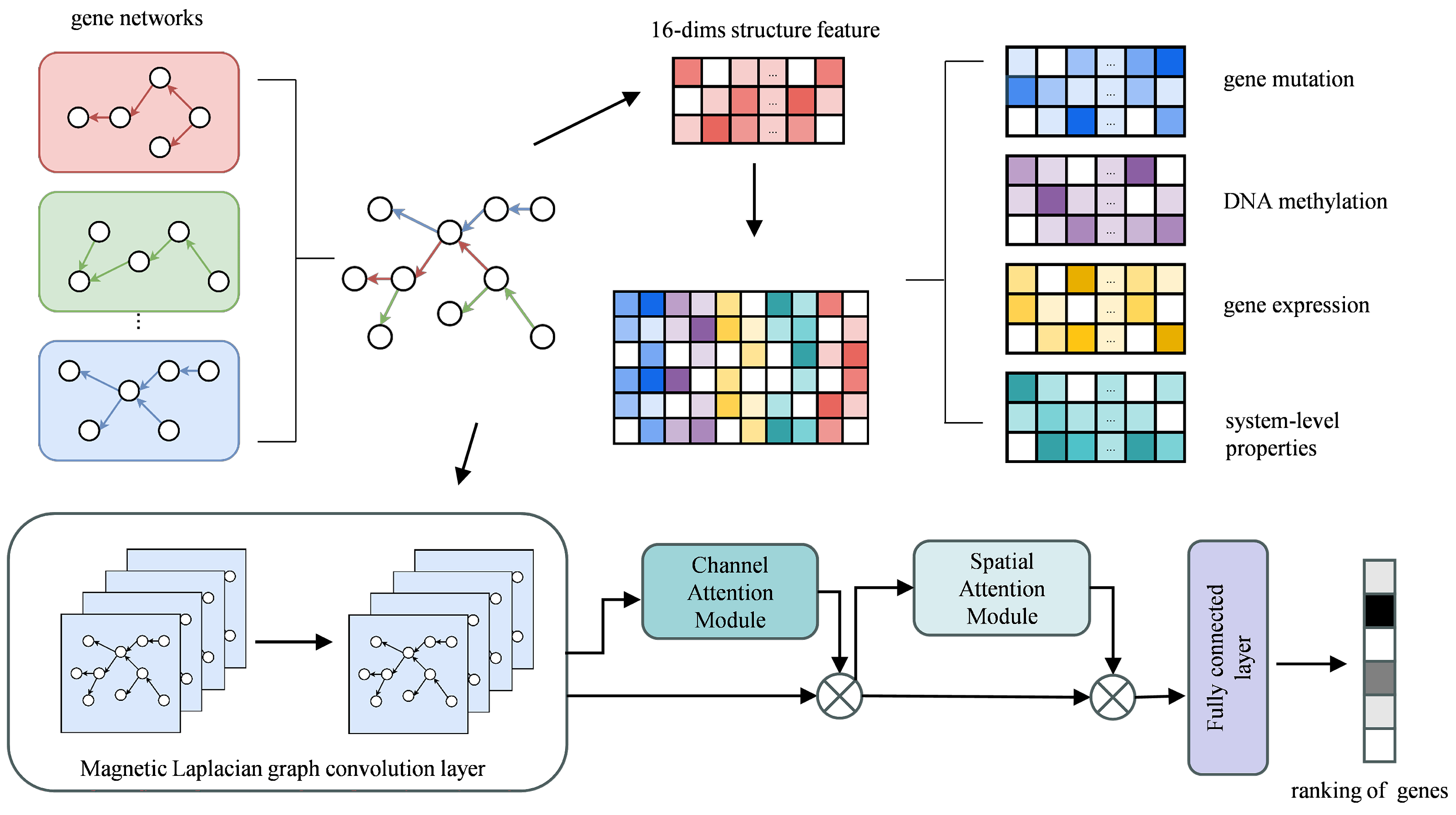

4.2. Framework of MDIGNN

4.3. Feature Enhancement

4.4. Constructing Graph Magnetic Laplacian

4.5. Attention Module

4.5.1. Channel Attention Module

4.5.2. Spatial Attention Module

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez-Jiménez, F.; Muiños, F.; Sentís, I.; Deu-Pons, J.; Reyes-Salazar, I.; Arnedo-Pac, C.; Mularoni, L.; Pich, O.; Bonet, J.; Kranas, H.; et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dees, N.D.; Zhang, Q.; Kandoth, C.; Wendl, M.C.; Schierding, W.; Koboldt, D.C.; Mooney, T.B.; Callaway, M.B.; Dooling, D.; Mardis, E.R.; et al. MuSiC: Identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.S.; Stojanov, P.; Polak, P.; Kryukov, G.V.; Cibulskis, K.; Sivachenko, A.; Carter, S.L.; Stewart, C.; Mermel, C.H.; Roberts, S.A.; et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 2013, 499, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; McConechy, M.K.; Horlings, H.M.; Ha, G.; Chun Chan, F.; Funnell, T.; Mullaly, S.C.; Reimand, J.; Bashashati, A.; Bader, G.D.; et al. Systematic analysis of somatic mutations impacting gene expression in 12 tumour types. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, O.; Stoven, V.; Vert, J.P. LOTUS: A single-and multitask machine learning algorithm for the prediction of cancer driver genes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Qian, X.; Cheng, W.C.; Liu, S.H.; Hua, X.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, P.; et al. DriverML: A machine learning algorithm for identifying driver genes in cancer sequencing studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 20, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Sasse, R.; Budach, S.; Hnisz, D.; Marsico, A. Integration of multiomics data with graph convolutional networks to identify new cancer genes and their associated molecular mechanisms. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Tang, Q.; Dai, W.; Chen, T. Improving cancer driver gene identification using multi-task learning on graph convolutional network. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. MCDHGN: Heterogeneous network-based cancer driver gene prediction and interpretability analysis. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.W.; Xu, J.Y.; Zhang, T. DGMP: Identifying cancer driver genes by jointing DGCN and MLP from multi-omics genomic data. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Gu, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Z. MODIG: Integrating multi-omics and multi-dimensional gene network for cancer driver gene identification based on graph attention network model. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4901–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.W.; Xie, M.Y.; Li, Y. A novel heterophilic graph diffusion convolutional network for identifying cancer driver genes. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Wu, R.; Dai, W.; Yu, N. Identifying cancer driver genes based on multi-view heterogeneous graph convolutional network and self-attention mechanism. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Phillips, S.; Kundra, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, J.E.; Yaeger, R.; Soumerai, T.; Nissan, M.H.; et al. OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, PO.17.00011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.; Zhao, E.Y.; Grewal, J.; Jones, M.R.; Jones, S.J. CancerMine: A literature-mined resource for drivers, oncogenes and tumor suppressors in cancer. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sun, M.M.; Zhang, G.G.; Yang, J.; Chen, K.S.; Xu, W.W.; Li, B. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvar, M.T.; Rashidan, K.; Arsam, N.; Rasouli-Saravani, A.; Yadegari, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Asgari, Z.; Vanan, A.G.; Ghorbaninezhad, F.; Tahmasebi, S. Th17 cell function in cancers: Immunosuppressive agents or anti-tumor allies? Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Pan, W.W.; Liu, S.B.; Shen, Z.F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.L. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursunel, M.A.; Esendagli, G. The untold story of IFN-γ in cancer biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 31, 73–81, Correction in Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017, 35, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.A.; McKenzie, A.N. TH2 cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takegahara, N.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y. Unraveling the intricacies of osteoclast differentiation and maturation: Insight into novel therapeutic strategies for bone-destructive diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Zhan, C.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ren, B.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Y. Blood lipid metabolic biomarkers are emerging as significant prognostic indicators for survival in cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozza, C.; Cinausero, M.; Iacono, D.; Puglisi, F. Hepatitis B and cancer: A practical guide for the oncologist. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2016, 98, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Overexpression of Forkhead box L1 (FOXL1) inhibits the proliferation and invasion of breast Cancer cells. Oncol. Res. 2017, 25, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Q.; Yang, F.P.; Li, W.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.C.; Che, J.P.; Huang, J.H.; Zheng, J.H. Foxl1 inhibits tumor invasion and predicts outcome in human renal cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 7, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, C.; Wen, H.; Wang, S.; Shu, G.; Wang, M.; Yi, H.; Guo, K.; Pan, Q.; Yin, G. Potential prognosis and immunotherapy predictor TFAP2A in pan-cancer. Aging 2024, 16, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, Q.; Wei, G.H. The role of HOX transcription factors in cancer predisposition and progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Luo, Z.; Tang, J.; Tian, J.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, T. Transcription factor NFIC functions as a tumor suppressor in lung squamous cell carcinoma progression by modulating lncRNA CASC2. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, N.; Gonzalez, J.B.M.; Srivastava, V.K.; Alanazi, B.; Alanazi, R.N.; Hughes, O.M.; O’Neill, N.S.; Gilkes, A.F.; Ashley, N.; Deshpande, S.; et al. Nuclear factor IC overexpression promotes monocytic development and cell survival in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2023, 37, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Wang, A.; Xue, M.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M. FOXA1 and FOXA2: The regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, M.; Shen, T.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Lu, Z. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis reveals EPHB2 is a novel predictive biomarker for prognosis and immunotherapy response. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.; Kołat, D.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, W. Crucial role of the transcription factors family activator protein 2 in cancer: Current clue and views. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Shi, Y.; Sun, L.; Gorczynski, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Spaner, D. PPAR-delta promotes survival of breast cancer cells in harsh metabolic conditions. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeter, C.R.; Yang, T.; Wang, J.; Chao, H.P.; Tang, D.G. Concise review: NANOG in cancer stem cells and tumor development: An update and outstanding questions. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 2381–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulsen, J.; Misetic, H.; Yau, C.; Ciccarelli, F.D. Pan-cancer detection of driver genes at the single-patient resolution. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.P.; Wu, C.; Miao, H.; Wu, H. RegNetwork: An integrated database of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory networks in human and mouse. Database 2015, 2015, bav095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shim, H.; Shin, D.; Shim, J.E.; Ko, Y.; Shin, J.; Kim, H.; Cho, A.; Kim, E.; Lee, T.; et al. TRRUST: A reference database of human transcriptional regulatory interactions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Rigor, P.; Baldi, P. MotifMap: A human genome-wide map of candidate regulatory motif sites. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovolenta, L.; Acencio, M.; Lemke, N. HTRIdb: An open-access database for experimentally verified human transcriptional regulation interactions. Nat. Preced. 2012, 13, 405. [Google Scholar]

- Van Landeghem, S.; Hakala, K.; Rönnqvist, S.; Salakoski, T.; Van de Peer, Y.; Ginter, F. Exploring biomolecular literature with EVEX: Connecting genes through events, homology, and indirect associations. Adv. Bioinform. 2012, 2012, 582765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathelier, A.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, A.W.; Parcy, F.; Worsley-Hunt, R.; Arenillas, D.J.; Buchman, S.; Chen, C.y.; Chou, A.; Ienasescu, H.; et al. JASPAR 2014: An extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D142–D147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, A.; Xu, H.; Krishnan, J.; Berger, S.I.; Mazloom, A.R.; Ma’ayan, A. ChEA: Transcription factor regulation inferred from integrating genome-wide ChIP-X experiments. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2438–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, E.; Good, P.; Guyer, M.; Kamholz, S.; Liefer, L.; Wetterstrand, K.; Collins, F.; Gingeras, T.; Kampa, D.; Sekinger, E.; et al. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia of DNA elements) project. Science 2004, 306, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, V.; Kel-Margoulis, O.V.; Fricke, E.; Liebich, I.; Land, S.; Barre-Dirrie, A.; Reuter, I.; Chekmenev, D.; Krull, M.; Hornischer, K.; et al. TRANSFAC® and its module TRANSCompel®: Transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D108–D110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamburov, A.; Stelzl, U.; Lehrach, H.; Herwig, R. The ConsensusPathDB interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D793–D800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razick, S.; Magklaras, G.; Donaldson, I.M. iRefIndex: A consolidated protein interaction database with provenance. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.K.; Carlin, D.E.; Yu, M.K.; Zhang, W.; Kreisberg, J.F.; Tamayo, P.; Ideker, T. Systematic evaluation of molecular networks for discovery of disease genes. Cell Syst. 2018, 6, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Cheng, J.; Cao, S.; Pan, X.; Shen, H.B.; Jin, C.; Yuan, Y. Integration of multi-source gene interaction networks and omics data with graph attention networks to identify novel disease genes. bioRxiv 2023, 41, btaf181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repana, D.; Nulsen, J.; Dressler, L.; Bortolomeazzi, M.; Venkata, S.K.; Tourna, A.; Yakovleva, A.; Palmieri, T.; Ciccarelli, F.D. The Network of Cancer Genes (NCG): A comprehensive catalogue of known and candidate cancer genes from cancer sequencing screens. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Brugnone, N.; Perlmutter, M.; Hirn, M. Magnet: A neural network for directed graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 27003–27015. [Google Scholar]

| Hyperparameter | Supernet Size |

|---|---|

| num of filters | 64 |

| K for cheb series | 1 |

| layer | 2 |

| dropout rate | 0.5 |

| learning rate | 1 × 10−3 |

| weight decay | 5 × 10−3 |

| Method | AUROC | AUPR | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMOJI | 0.8123 | 0.6758 | 0.7139 | 0.8028 | 0.6825 | 0.4711 | 0.4287 |

| MODIG | 0.8941 | 0.7818 | 0.8533 | 0.6423 | 0.9276 | 0.7575 | 0.6029 |

| MTGCN | 0.9102 | 0.8334 | 0.8650 | 0.7296 | 0.9127 | 0.7464 | 0.6471 |

| HGDC | 0.8468 | 0.7620 | 0.7545 | 0.6681 | 0.8101 | 0.6978 | 0.5654 |

| MRNGCN | 0.9061 | 0.8265 | 0.8672 | 0.7155 | 0.9206 | 0.7605 | 0.6491 |

| MCDHCN | 0.8703 | 0.7971 | 0.8437 | 0.5915 | 0.9325 | 0.7554 | 0.5708 |

| DGMP | 0.8275 | 0.7413 | 0.8239 | 0.4873 | 0.9425 | 0.7489 | 0.5028 |

| MDIGNN | 0.9302 | 0.8470 | 0.8720 | 0.7420 | 0.9393 | 0.7959 | 0.6701 |

| Method | AUROC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|

| Use GCN layer | 0.9012 | 0.8136 |

| Only PPI | 0.9202 | 0.8410 |

| Only KEGG | 0.9244 | 0.8394 |

| Only RegNetwork | 0.9255 | 0.8408 |

| Without sys | 0.9229 | 0.8334 |

| Without feature enhancement | 0.8789 | 0.7741 |

| Without edgedropout | 0.9201 | 0.8396 |

| Without channel attention | 0.9276 | 0.8402 |

| Without spatial attention | 0.9262 | 0.8420 |

| Without attention | 0.9279 | 0.8397 |

| MDIGNN | 0.9302 | 0.8470 |

| Gene | Function |

|---|---|

| FOXL1 | The expression of FOXL1 is typically downregulated in kidney and breast cancer, and its high expression is often associated with better prognosis [27,28]. |

| TFAP2A | The mRNA expression level of TFAP2A is elevated, and genetic alterations of this gene are commonly found in many types of cancer [29]. |

| HOXA5 | Overexpression of HOXA5 is linked to apoptosis in various cancers, including breast, lung, and cervical cancer [30]. |

| NFIC | NFIC exhibits a complex dual role in cancers, functioning as either a tumor suppressor or an oncogenic factor [31,32]. |

| FOXA2 | FOXA2 plays various biological roles in the development and progression of tumors by regulating the expression of multiple genes involved in core pathways of tumorigenesis and chemotherapy resistance [33]. |

| EPHB2 | EPHB2 dysregulation has been noted in a range of cancer types, where it shows important diagnostic and prognostic significance [34]. |

| TFAP2C | The role of TFAP2C in tumor proliferation, invasion, modulation of the immune microenvironment, and treatment response makes it a candidate for both prognosis and therapy [35]. |

| PPARD | PPARD aids cancer cell survival under chemotherapy conditions by regulating cell metabolism and stress responses [36]. |

| USF2 | USF2 is supposed to play significant roles in metabolism, tissue protection, and tumor development. |

| NANOG | NANOG is abnormally overexpressed in diverse cancer and is associated with tumor progression, metastasis, and prognosis [37]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, T. Integrating Multi-Source Directed Gene Networks and Multi-Omics Data to Identify Cancer Driver Genes Based on Graph Neural Networks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412132

Jiang Y, Liu Y, Qi R, Li S, Zhang T. Integrating Multi-Source Directed Gene Networks and Multi-Omics Data to Identify Cancer Driver Genes Based on Graph Neural Networks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412132

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yuetong, Yunjiong Liu, Ruoyao Qi, Shaowei Li, and Tianying Zhang. 2025. "Integrating Multi-Source Directed Gene Networks and Multi-Omics Data to Identify Cancer Driver Genes Based on Graph Neural Networks" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412132

APA StyleJiang, Y., Liu, Y., Qi, R., Li, S., & Zhang, T. (2025). Integrating Multi-Source Directed Gene Networks and Multi-Omics Data to Identify Cancer Driver Genes Based on Graph Neural Networks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412132