Physicochemical Characterisation of Ceftobiprole and Investigation of the Biological Properties of Its Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. DFT-Assisted NMR Analysis

2.2. Physicochemical Properties of CBP

2.2.1. Considerations on the Hydrophobic Behaviour and the Solubility of CBP

2.2.2. Acid-Base Properties

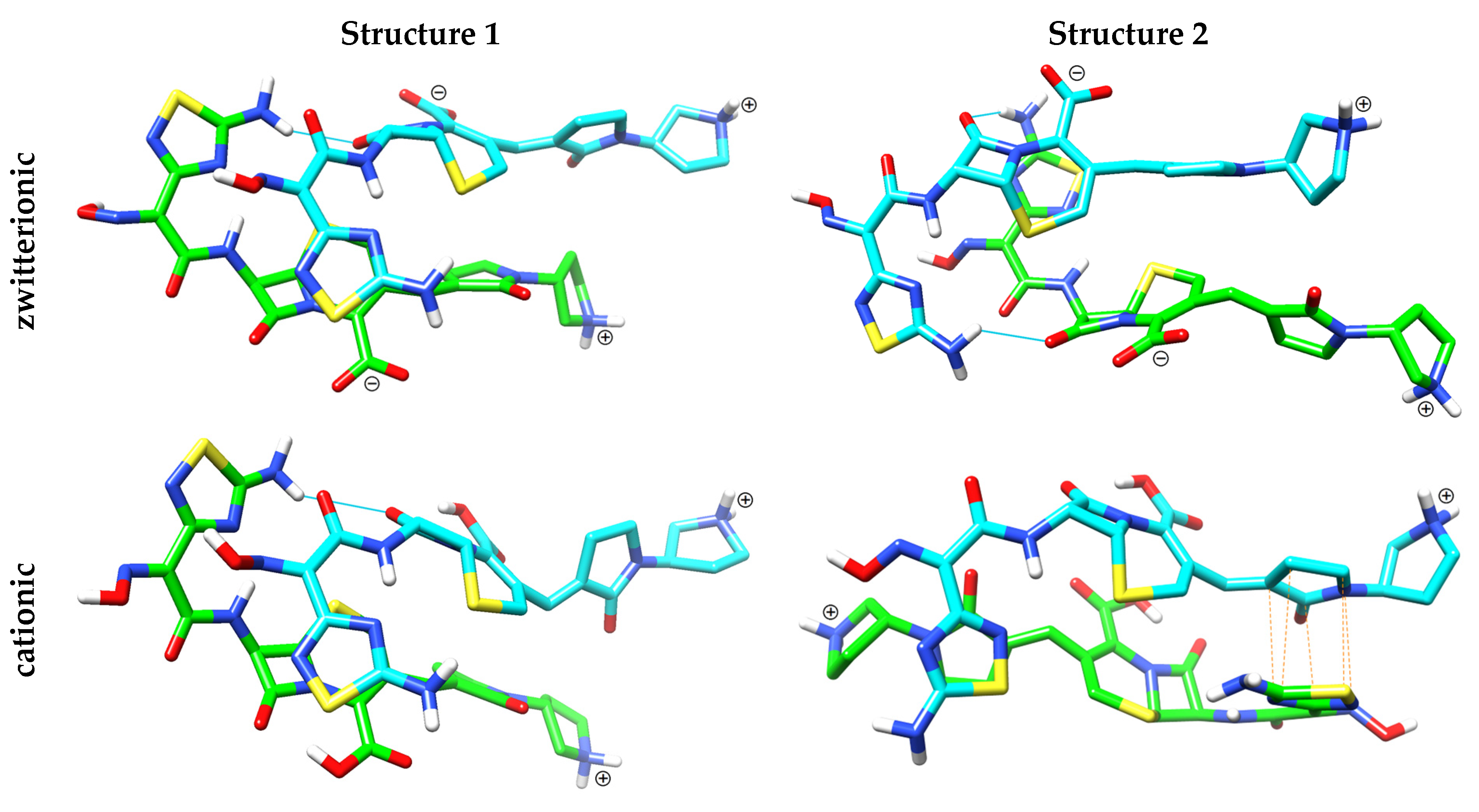

2.2.3. Computational Studies of Intermolecular Interactions at Different pH

2.3. Biological Properties of a CBP-CD Drug Delivery System

2.3.1. Antibacterial Activity

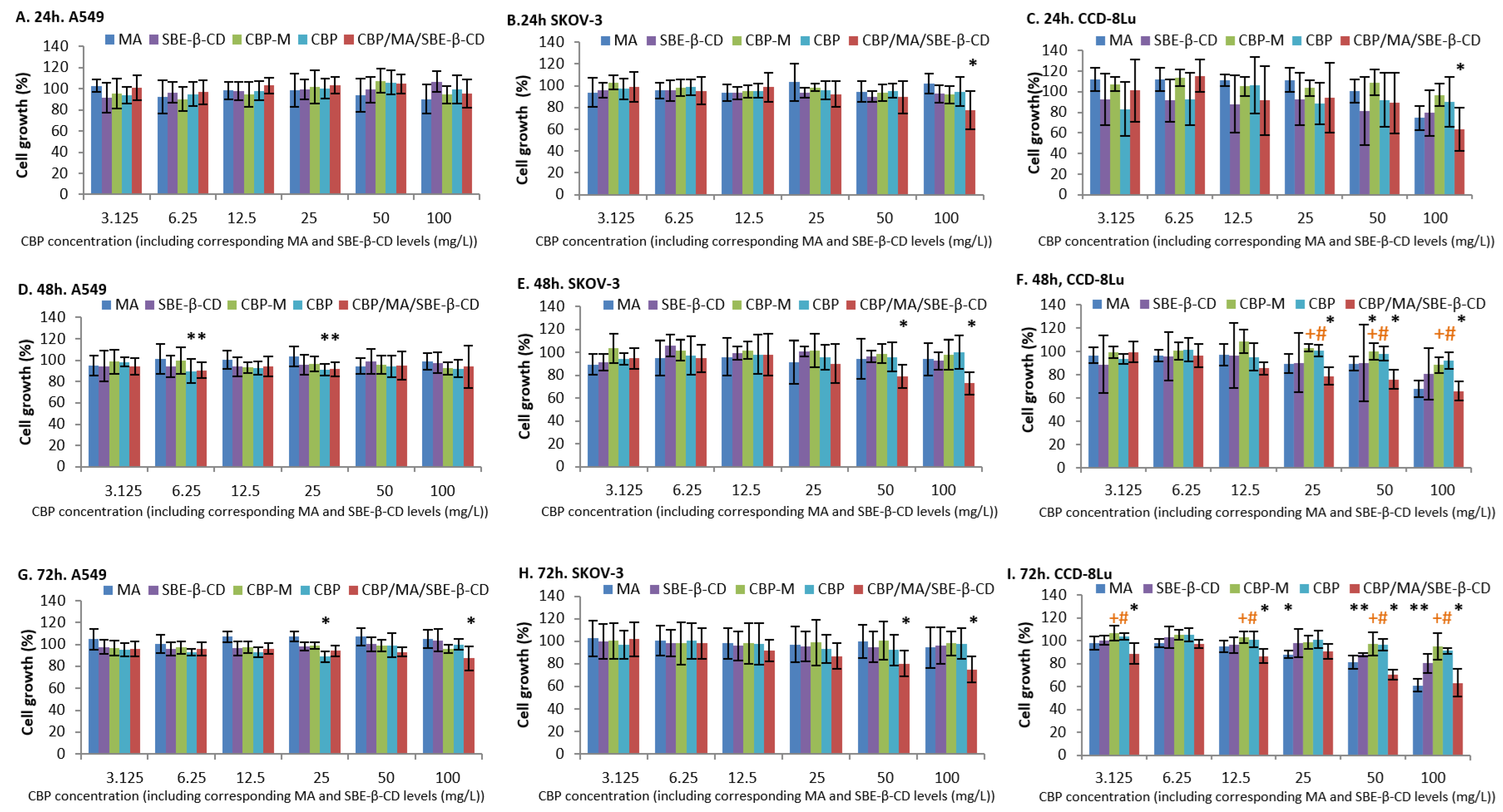

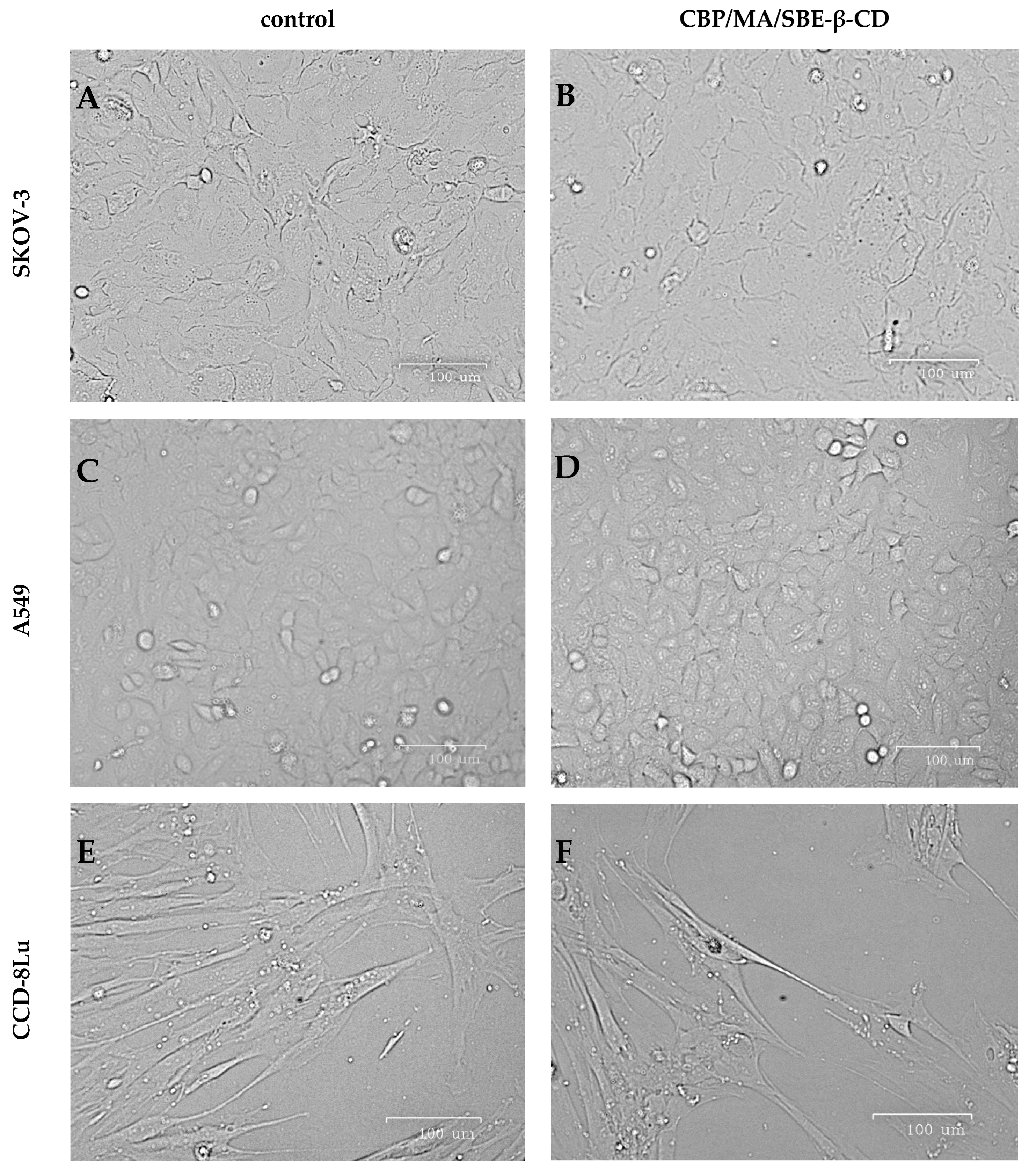

2.3.2. Cytotoxicity Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. HPLC Studies

3.3. CZE Studies

3.4. NMR Studies

3.5. ATR-FTIR Studies

3.6. DFT Calculations

3.7. MD Simulations

3.7.1. Performing the Simulation

3.7.2. Trajectory Post-Processing

3.8. Antimicrobial Activity Studies

3.9. Cytotoxicity Studies

3.9.1. MTT Assay

3.9.2. Statistical Analysis

3.9.3. Morphology Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lupia, T.; Pallotto, C.; Corcione, S.; Boglione, L.; De Rosa, F.G. Ceftobiprole Perspective: Current and Potential Future Indications. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug and Health Product Portal (Canada). Summary Basis of Decision for Zeftera. Available online: https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/review-documents/resource/SBD00163 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Antibiotic for Three Different Uses. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-antibiotic-three-different-uses (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (United Kingdom). Public Assessment Report—Zevtera 500 mg Powder for Concentrate for Solution for Infusion (UK/H/5304/001/DC). Available online: https://products.mhra.gov.uk/search/?search=zevtera (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures—Human (CMDh). EU PSUR Work Sharing Summary Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.hma.eu/fileadmin/dateien/Human_Medicines/CMD_h_/Pharmacovigilance_Legislation/PSUR/Outcome_of_informal_PSUR_WS_procedures/Ceftobiprole_SmAR_09_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. List of Nationally Authorised Medicinal Products. Active Substance(s): Ceftobiprole. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/psusa/ceftobiprole-list-nationally-authorised-medicinal-products-psusa-00010734-202411_en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Refusal of the Marketing Authorisation for Zeftera (Ceftobiprole). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop-initial/questions-and-answers-recommendation-refusal-marketing-authorisation-zeftera_en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Zeftera (Previously Zevtera). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zeftera (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Boczar, D.; Bocian, W.; Sitkowski, J.; Pioruńska, K.; Michalska, K. Development of a Cyclodextrin-Based Drug Delivery System to Improve the Physicochemical Properties of Ceftobiprole as a Model Antibiotic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angehrn, P. Vinyl Pyrrolidine Cephalosporins with Basic Substituents. EP 0849269 A1, 11 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Angehrn, P.; Hebeisen, P.; Heinze-Krauss, I.; Page, M.; Runt, V. Vinyl-Pyrrolidinone Cephalosporins. US 5981519A, 28 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti, P.; Hebeisen, P.; Heubes, M.; Pozzi, G.; Schleimer, M. New Crystal Polymorphs of Ceftobiprole. WO 2010072672A1, 1 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wieder, M.; Fass, J.; Chodera, J.D. Fitting quantum machine learning potentials to experimental free energy data: Predicting tautomer ratios in solution. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 11364–11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DrugBank Online. Ceftobiprole: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB04918 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Boczar, D.; Bus, K.; Michalska, K. Study of Degradation Kinetics and Structural Analysis of Related Substances of Ceftobiprole by HPLC with UV and MS/MS Detection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boczar, D.; Michalska, K. Investigation of the Affinity of Ceftobiprole for Selected Cyclodextrins Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations and HPLC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczar, D.; Michalska, K. Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes with Antibiotics and Antibacterial Agents as Drug-Delivery Systems-A Pharmaceutical Perspective. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.T.; Boyd, R.N. Organic Chemistry; Benjamin-Cummings Pub Co: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, V.; Colón, A.; Barrientos, C.; León, I. Stabilization of Zwitterionic Versus Canonical Glycine by DMSO Molecules. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Opallage, P.M.; Dunn, R.C. Investigation of induced electroosmotic flow in small-scale capillary electrophoresis devices: Strategies for control and reversal. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremminger, P.; Ludescher, J.; Sturm, H. Method for the Production of Ceftobiprole Medocaril. US 20120108807 A1, 25 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ChemAxon. Chemicalize. Available online: https://chemicalize.com/welcome (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M. Epik: A software program for pKaprediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, J.; Nowicki, K.; Durka, K.; Marek-Urban, P.H.; Wińska, P.; Stępniewski, T.; Woźniak, K.; Laudy, A.E.; Luliński, S. Oxazoline scaffold in synthesis of benzosiloxaboroles and related ring-expanded heterocycles: Diverse reactivity, structural peculiarities and antimicrobial activity. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23099–23117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 15.0, Valid from 2025-01-01. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/bacteria/clinical-breakpoints-and-interpretation/clinical-breakpoint-tables/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Health Products Regulatory Authority (Ireland). Adaluzis 500mg, Powder for Concentrate for Solution for Infusion. Summary of Product Characteristics (Date of Revision of the Text: February 2025). Available online: https://assets.hpra.ie/products/Human/30880/Licence_PA23450-003-001_07022025123450.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Indrayanto, G.; Putra, G.S.; Suhud, F. Validation of in-vitro bioassay methods: Application in herbal drug research. In Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology; Al-Majed, A.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 46, pp. 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, M.; Omolo, C.A.; Agrawal, N.; Walvekar, P.; Waddad, A.Y.; Mocktar, C.; Ramdhin, C.; Govender, T. Supramolecular amphiphiles of Beta-cyclodextrin and Oleylamine for enhancement of vancomycin delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 574, 118881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, S.; Blasier, R.; Markel, D.C.; Mao, G.; Shi, T.; Ren, W. Cyclodextrin-erythromycin complexes as a drug delivery device for orthopedic application. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 3173–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konečná, K.; Diepoltová, A.; Holmanová, P.; Jand’ourek, O.; Vejsová, M.; Voxová, B.; Bárta, P.; Maixnerová, J.; Trejtnar, F.; Kučerová-Chlupáčová, M. Comprehensive insight into anti-staphylococcal and anti-enterococcal action of brominated and chlorinated pyrazine-based chalcones. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 912467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jităreanu, A.; Agoroaei, L.; Caba, I.-C.; Cojocaru, F.-D.; Vereștiuc, L.; Vieriu, M.; Mârțu, I. The Evolution of In Vitro Toxicity Assessment Methods for Oral Cavity Tissues—From 2D Cell Cultures to Organ-on-a-Chip. Toxics 2025, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, D. OpenVnmrJ; Version 3.1; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, P.J.; Devlin, F.J.; Chabalowski, C.F.; Frisch, M.J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, P.C.; Pople, J.A. The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavachari, K.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J. Ab initio study of ionic solutions by a polarizable continuum dielectric model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 286, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, J.R.; Trucks, G.W.; Keith, T.A.; Frisch, M.J. A comparison of models for calculating nuclear magnetic resonance shielding tensors. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 5497–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Ceftobiprole. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ceftobiprole (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminf. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Belfon, K.; Ben-Shalom, I.Y.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Darden, T.A.; Duke, R.E.; Giambasu, G.; et al. AMBER 2020; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.M.; Wang, W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2006, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Wolf, R.M.; Caldwell, J.W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa da Silva, A.W.; Vranken, W.F. ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemkul, J.A. From Proteins to Perturbed Hamiltonians: A Suite of Tutorials for the GROMACS-2018 Molecular Simulation Package [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 1, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud-Agrawal, N.; Denning, E.J.; Woolf, T.B.; Beckstein, O. MDAnalysis: A toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowers, R.J.; Linke, M.; Barnoud, J.; Reddy, T.J.E.; Melo, M.N.; Seyler, S.L.; Domański, J.; Dotson, D.L.; Buchoux, S.; Kenney, I.M.; et al. MDAnalysis: A Python Package for the Rapid Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Simulations. In Proceedings of the 15th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 11–17 July 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Approved Standard, CLSI Guideline M07-A9, 9th ed.; Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents, CLSI Guideline M26-A; Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Atom | NMR Chemical Shift (ppm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1H (exp.) | 13C (exp.) (a) | 13C (calc.) (b) | |

| 2 | 3.69; 3.63 | 25.7 | 27.1 |

| 3 | - | 116.2 | 114.7 |

| 4 | - | 133.6 | 142.0 |

| 6 | 5.14 | 57.4 | 60.0 |

| 7 | 5.77 | 58.9 | 55.6 |

| 8 | - | 163.7 | 162.8 |

| 10 | - | 168.9 | 166.4 |

| 1′ | 6.91 | 127.2 | 130.9 |

| 2′ | - | 132.1 | 131.2 |

| 3′ | 2.87 | 23.7 | 21.1 |

| 4′ | 3.45 | 43.4 | 44.5 |

| 6′ | - | 171.2 | 171.1 |

| 7′ | 4.53 | 52.1 | 51.6 |

| 8′ | 3.44; 3.37 | 46.6 | 48.5 |

| 10′ | 3.44; 3.26 | 45.1 | 43.8 |

| 11′ | 2.24; 2.11 | 27.2 | 25.9 |

| 2″ | - | 164.4 | 162.5 |

| 3″ | - | 147.0 | 144.3 |

| 4″ | - | 161.4 | 162.7 |

| 6″ | - | 184.4 | 183.5 |

| Chemical Shifts δ (ppm) of Selected Protons in CBP Molecule | |

|---|---|

| In DMSO [10,11] | In DMSO with CF3COOD [21] |

| 8.1 ppm (singlet, 2H) | 8.1 ppm (singlet, 2H) |

| 9.5 ppm (doublet, 1H) | 8.9 ppm (singlet, 2H) |

| 10.3 ppm (broad singlet, 1H) | 9.5 ppm (doublet, 1H) |

| 12.0 ppm (broad singlet, 1H) | 12.0 ppm (broad singlet, 1H) |

| Structure | The Pair of Interacting Rings | Perpendicular Inter-Planar Distance (Å) | Lateral Displacement (Å) | Tilt (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zwitterionic | 1 | thiadiazole-dihydrothiazine | 3.95 ± 0.25 | 1.34 ± 0.77 | 14.7 ± 9.6 |

| 2 | dihydrothiazine-thiadiazole | 3.94 ± 0.25 | 1.54 ± 0.77 | 19.6 ± 11.9 | |

| cationic | 1 | thiadiazole-dihydrothiazine | 3.92 ± 0.24 | 2.00 ± 0.78 | 15.4 ± 10.0 |

| 2 | 2-pyrrolidone-thiadiazole | 3.72 ± 0.26 | 1.30 ± 0.59 | 22.2 ± 10.6 | |

| thiadiazole-2-pyrrolidone | 3.72 ± 0.26 | 1.28 ± 0.59 | 20.9 ± 9.9 |

| Strains | MIC (mg/L) [MBC (mg/L)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBP-M | CBP | CBP/MA/SBE-β-CD | SBE-β-CD | MA | |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 MSSA | 0.5 [>8] | 0.25 [>8] | 0.25 [>8] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 MSSE | 0.25 [0.5] | 0.25 [0.5] | 0.25 [0.5] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 MRSA | 1 [2] | 1 [1] | 1 [1] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus 664 MRSA | 4 [>8] | 2 [>8] | 4 [>8] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus 1576 MRSA | 2 [>8] | 2 [2] | 2 [>8] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus 1712 MRSA | 2 [2] | 1 [2] | 1 [2] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus 1991 MRSA | 2 [4] | 2 [2] | 2 [2] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. aureus 2541 MRSA | 4 [>8] | 4 [4] | 4 [>8] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 | 0.0078 [0.5] | 0.0039 [0.5] | 0.0078 [1] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. pneumoniae MUW 2/299o21 | 0.0156 [0.0156] | 0.0156 [0.0156] | 0.0156 [0.0156] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. pneumoniae MUW 3/39085 | 0.0625 [0.125] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| S. pneumoniae MUW 4/cw | 0.0156 [0.0156] | 0.0078 [0.0156] | 0.0078 [0.0156] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| Strains | MIC (mg/L) [MBC (mg/L)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBP-M | CBP | CBP/MA/SBE-β-CD | SBE-βCD | MA | |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.125 [0.25] | 0.0625 [0.125] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| E. coli NCTC 8196 | 0.0625 [0.0625] | 0.03125 [0.03125] | 0.03125 [0.03125] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| E. coli NCTC 10538 | 0.125 [0.125] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| E. coli MUW 77 CMY-2(+) | 0.5 [1] | 0.25 [0.25] | 0.25 [0.25] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 0.25 [0.25] | 0.125 [0.0625] | 0.0625 [0.0625] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| K. pneumoniae MUW 78 CMY-2(+) | 4 [4] | 1 [4] | 1 [1] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 4 [8] | 4 [>8] | 2 [4] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

| A. baumannii ATCC 19606 | 8 [>8] | 4 [1] | 4 [>8] | >32 [>32] | >200 [>200] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boczar, D.; Bocian, W.; Małek, K.; Milczarek, M.; Laudy, A.E.; Michalska, K. Physicochemical Characterisation of Ceftobiprole and Investigation of the Biological Properties of Its Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412108

Boczar D, Bocian W, Małek K, Milczarek M, Laudy AE, Michalska K. Physicochemical Characterisation of Ceftobiprole and Investigation of the Biological Properties of Its Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412108

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoczar, Dariusz, Wojciech Bocian, Krystian Małek, Małgorzata Milczarek, Agnieszka Ewa Laudy, and Katarzyna Michalska. 2025. "Physicochemical Characterisation of Ceftobiprole and Investigation of the Biological Properties of Its Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery System" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412108

APA StyleBoczar, D., Bocian, W., Małek, K., Milczarek, M., Laudy, A. E., & Michalska, K. (2025). Physicochemical Characterisation of Ceftobiprole and Investigation of the Biological Properties of Its Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412108