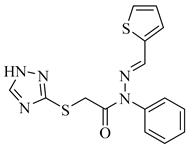

Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel 2-((1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide as Potential Antimicrobial Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

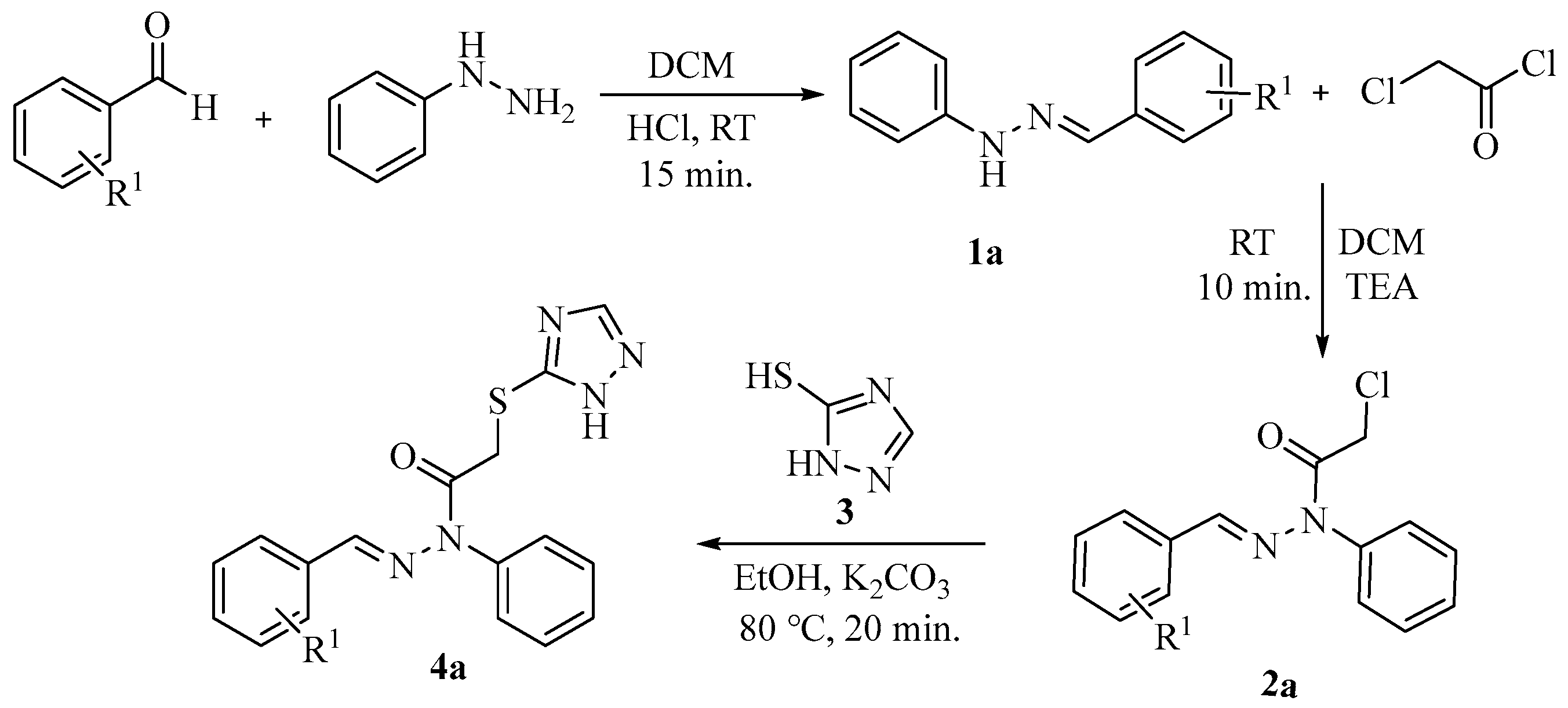

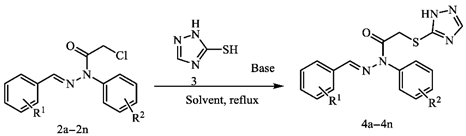

2.1. Chemistry

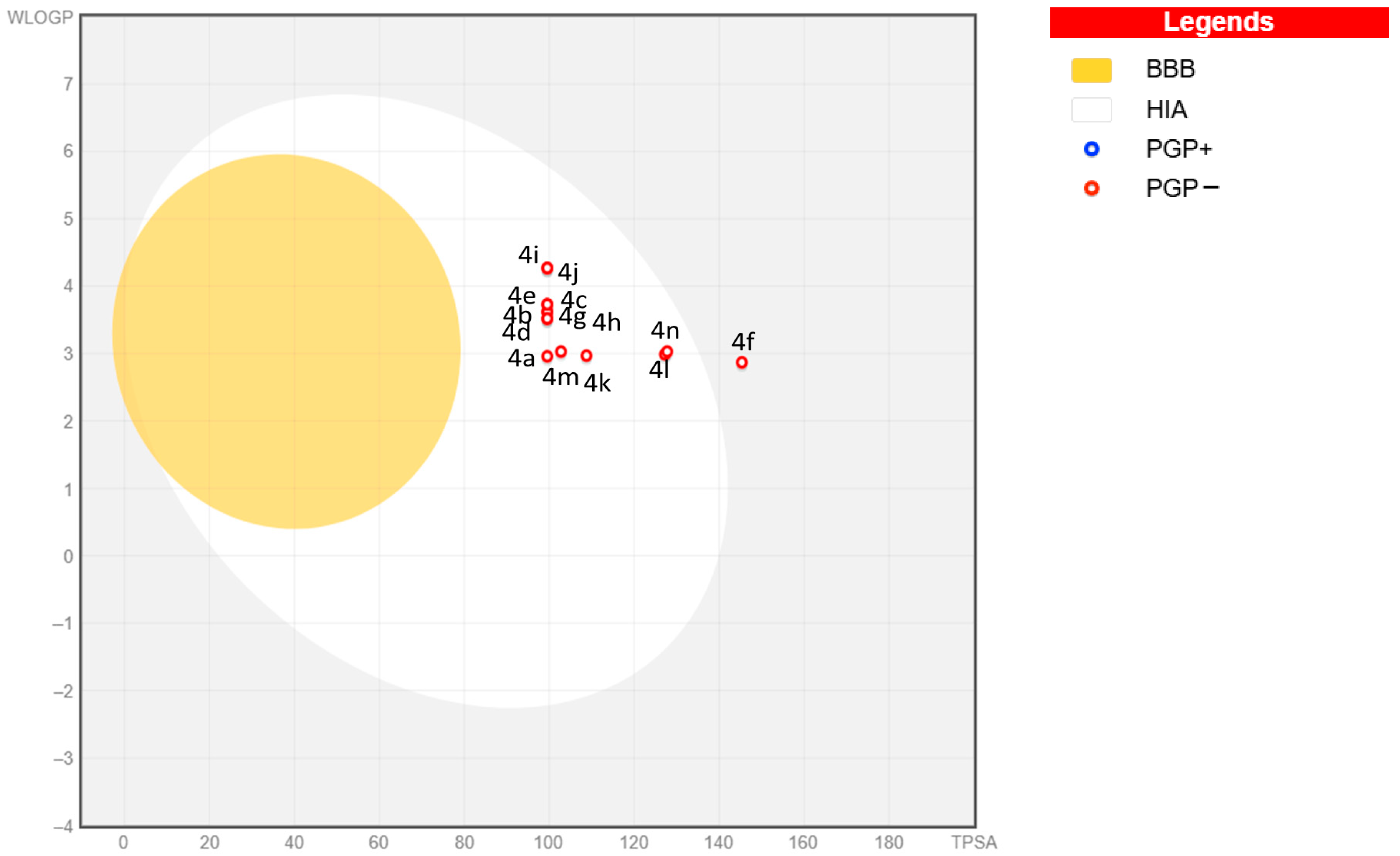

2.2. Evaluation of Physicochemical Characteristics

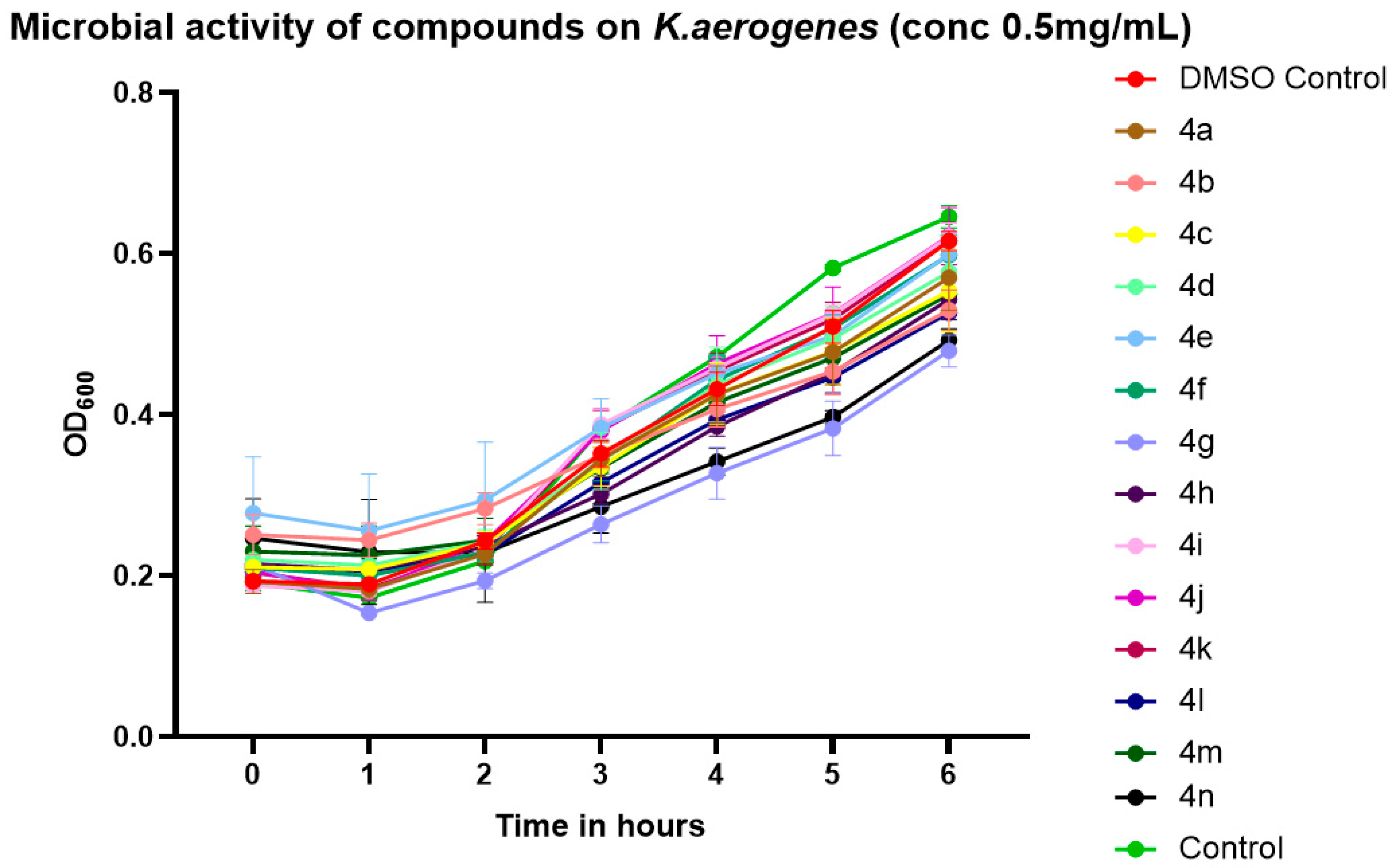

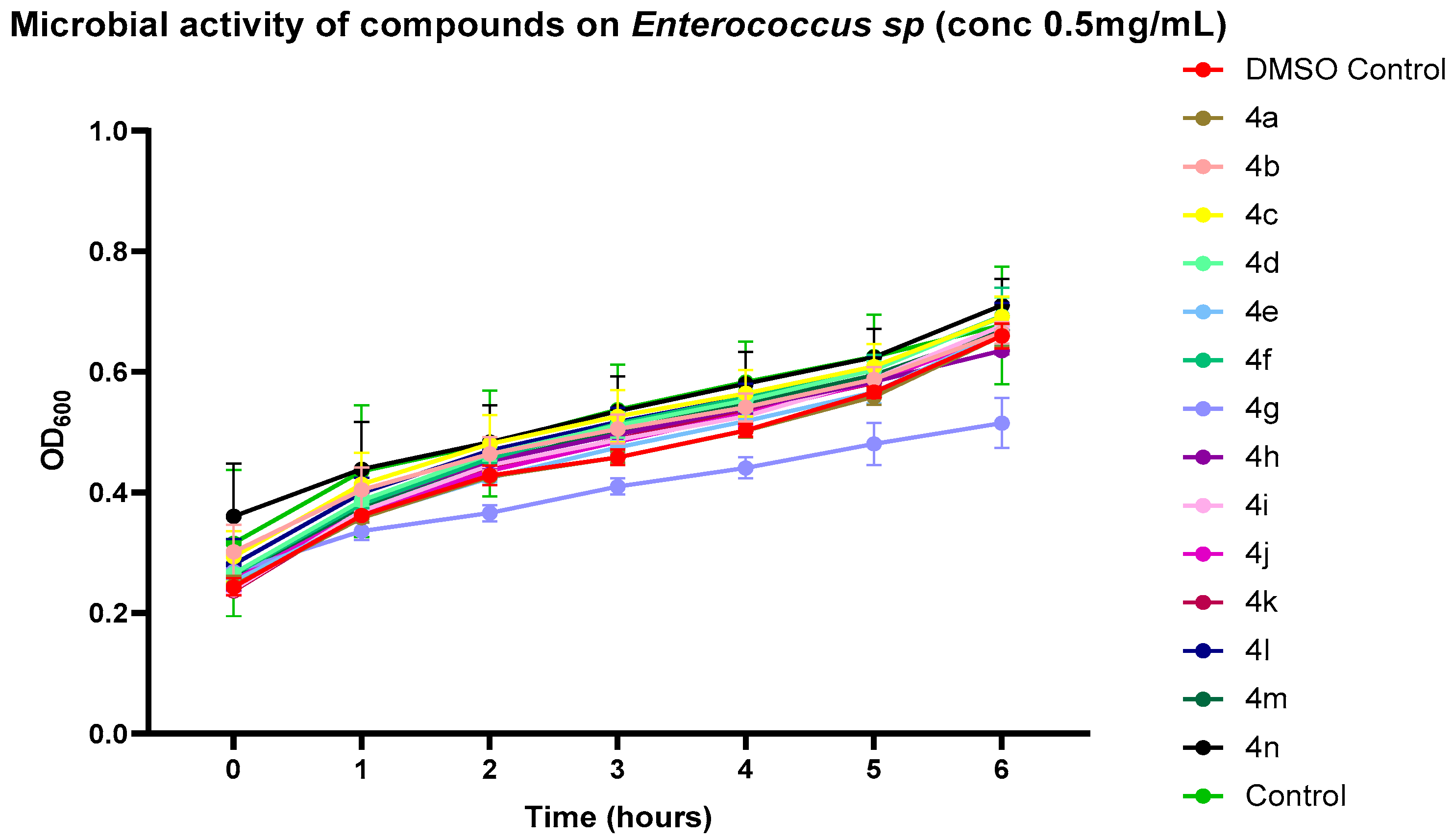

2.3. Preliminary Screening of Antibacterial Activity

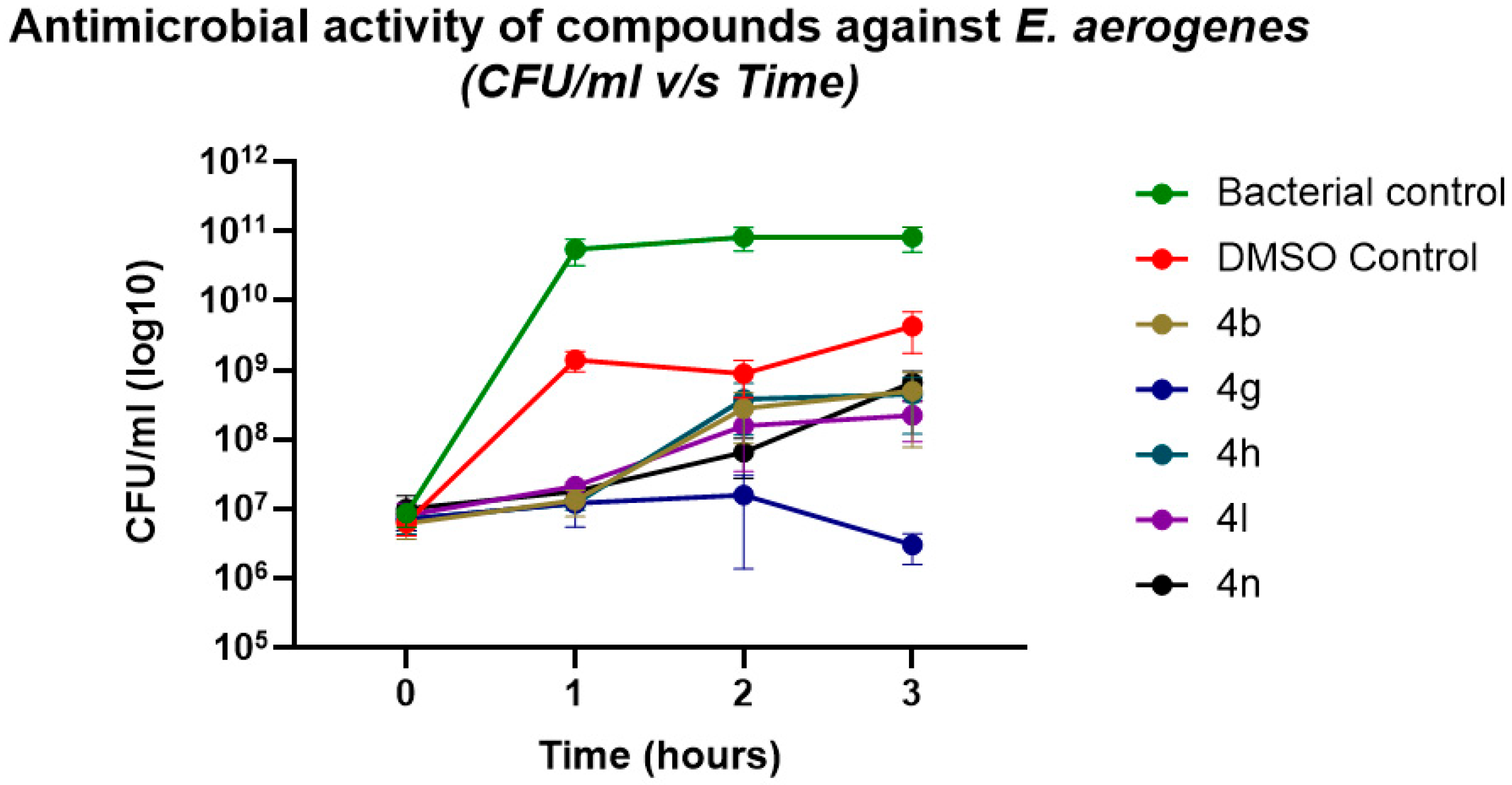

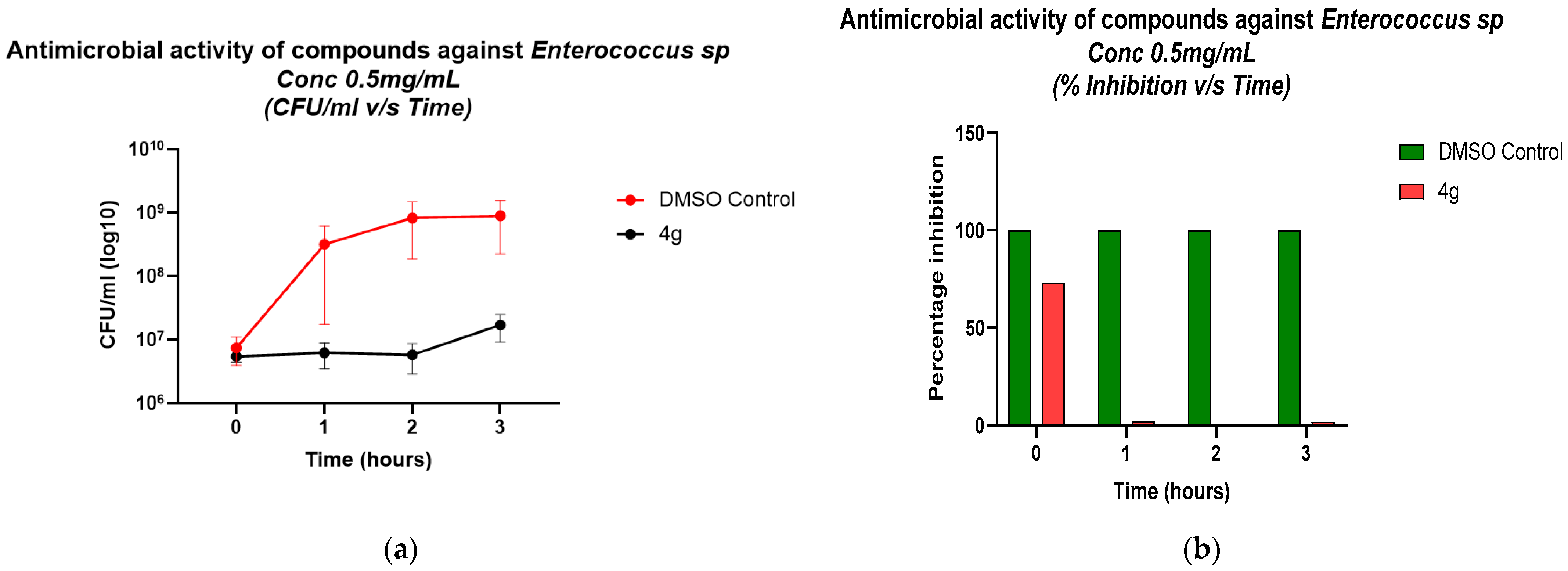

2.4. Validation of Antibacterial Activity Through Growth Kinetics and CFU Enumeration

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assessment of Compounds Using MTT Assay HEK Cell Lines

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Procedure for Synthesis of 1-Benzylidene-2-phenylhydrazine (1a–1n)

4.2. Procedure for Synthesis of E-1-Benzylidene-2-chloro phenylacetohydrazide (2a–2n)

4.3. Procedure for Synthesis of E-2-((1H-1,2,4-Triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide

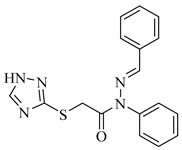

4.4. Spectral Data of Synthesized Compounds (4a–4n)

4.5. In Silico Analysis (ADME)

4.6. Solubility Optimization and Antibacterial Activity Evaluation

4.7. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

4.8. Growth Kinetics Assay

4.9. CFU Enumeration

4.10. Cytotoxicity Assessment Using MTT Assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| HEK | Human Embryonic Kidney |

| NCEs | New Chemical Entities |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| DIPEA | Diisopropylethylamine |

| H NMR | Hydrogen-1 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| C NMR | Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ESI MS | Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry |

| SAR | Structure-Activity Relationship |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| LB | Luria Bertani broth |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

References

- Sahoo, B.M.; Nagamounika, K.; Banik, K. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Schiff’s bases of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives and their anthelmintic activity. Artic. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2018, 95, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Huang, G. Antibacterial activity study of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 173, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channabasappa, V.; Kumar, K.A.; Vagish, C.B.; Sudeep, P.; Jayadevappa, H.P.; Kumar, A. 1,2,4-triazoles: Synthetic and medicinal perspectives. Artic. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2020, 12, 12950–12960. [Google Scholar]

- Pakes, G.E.; Brogden, R.N.; Heel, R.C.; Speight, T.M.; Avery, G.S. Drug Evaluations Triazolam: A Review of its Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in Patients with Insomnia. Drug Eval. 1981, 22, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, S.C.; Straub, B.F. Synthesis of N-Substituted 1,2,4-Triazoles. A Review; Bellwether Publishing, Ltd.: Columbia, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, A.R.; Pineiro, M.; Martins, J.M.; Barata, P.A.; Menezes, J.C. Identification of Alprazolam and Its Degradation Products Using LC-MS-MS; ARKAT USA, Inc.: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, J.D.; Wilner, K.D. Drug Interactions with Fluconazole Downloaded from. 2013. Available online: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Sahu, J.K.; Ganguly, S.; Kaushik, A. Triazoles: A valuable insight into recent developments and biological activities. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 11, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskas, L.; Udrenaite, E.; Gaidelis, P.; Brukštus, A. Synthesis of 5-(2-,3- and 4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol derivatives exhibiting anti-inflammatory activity. Farmaco 2004, 59, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samvelyan, M.A.; Ghochikyan, T.V.; Grigoryan, S.V.; Tamazyan, R.A.; Aivazyan, A.G. Alkylation of 1,2,4-triazole-3-thiols with haloalkanoic acid esters. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 53, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvà, M.C.; Romeo, G.; Guerrera, F.; Siracusa, M.; Salerno, L.; Russo, F.; Cagnotto, A.; Goegan, M.; Mennini, T. Triazole Derivatives as 5-HT 1A Serotonin Receptor Ligands. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozien, Z.A.; EL-Mahdy, A.F.M.; Markeb, A.A.; Ali, L.S.A.; El-Sherief, H.A.H. Synthesis of Schiff and Mannich bases of news-triazole derivatives and their potential applications for removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution and as antimicrobial agents. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 20184–20194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M.F.; Naser, N.H.; Hammud, N.H. Synthesis and preliminary pharmacological evaluation of new naproxen analogues having 1, 2, 4-triazole-3-thiol. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Chouhan, M.; Nair, V.A. A novel one-pot synthesis of 2-benzoylpyrroles from benzaldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangar, M.; Kashyap, N.; Kumar, K.; Goyal, S.; Nair, V.A. Imidazolidinone based chiral auxiliary mediated acetate aldol reactions of isatin derivatives and stereoselective synthesis of 3-substituted-3-hydroxy-2-oxindoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 7074–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatik, G.L.; Pal, A.; Mobin, S.M.; Nair, V.A. Stereochemical studies of 5-methyl-3-(substituted phenyl)-5-[(substituted phenyl) hydroxy methyl]-2-thiooxazolidin-4-ones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 3654–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Chouhan, M.; Sood, D.; Nair, V.A. An efficient one-pot synthesis of 2-benzylpyrroles and 3-benzylindoles. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 25, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, M.; Sharma, R.; Nair, V.A. Cp2ZrCl2-induced Reformatsky and Barbier reactions on isatins: An efficient synthesis of 3-substituted-3-hydroxyindolin-2-ones. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 25, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatik, G.L.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, V.; Chouhan, M.; Nair, V.A. Stereoselective synthesis of (S)-dapoxetine: A chiral auxiliary mediated approach. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 5991–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Jubeh, B.; Karaman, R. Resistance of gram-negative bacteria to current antibacterial agents and approaches to resolve it. Molecules 2020, 25, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubeh, B.; Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Resistance of gram-positive bacteria to current antibacterial agents and overcoming approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative: What Is the Difference? Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/gram-positive-vs-gram-negative (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Chathangad, S.N.; Vijayan, V.N.; George, J.A.; Sadhukhan, S. Mitigating Antimicrobial Resistance through Strategic Design of Multimodal Antibacterial Agents Based on 1,2,3-Triazole with Click Chemistry. ACS Bio. Med. Chem. Au 2025, 5, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethke, M.; Pieroni, M.; Weber, T.; Brönstrup, M.; Hammann, P.; Halby, L.; Arimondo, P.B.; Glaser, P.; Aigle, B.; Bode, H.B.; et al. Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Res. 2021, 5, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, L.A.; El-Feky, S.M.; Abou-Zeid, L.A.; Massoud, M.A.; Shokralla, S.G.; Eisa, H.M. Synthesis, Molecular Modeling of Novel 1,2,4-Triazole Derivatives with Potential Antimicrobial and Antiviral Activities. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/52003613 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Le Peng, Y.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, X.H.; Zhao, Z.G. Microwave-assisted synthesis and antibacterial activity of derivatives of 3-[1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-5-(4-fluorobenzylthio)-4H-1,2, 4-triazol-4-amine. Chem. Pap. 2014, 68, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, M.; Fu, X. Ultrasound-assisted, one-pot, three-component synthesis and antibacterial activities of novel indole derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazole and 1,2,4-triazole moieties. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2015, 18, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orek, C.; Koparir, P.; Koparir, M. N-cyclohexyl-2-[5-(4-pyridyl)-4-(p-tolyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-ylsulfanyl]-acetamide dihydrate: Synthesis, experimental, theoretical characterization and biological activities. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 97, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubie, S.; Prabitha, P.; Kumar, R.R.; Kalirajan, R.; Gayathri, R.; Sankar, S.; Elango, K. Design, synthesis, and docking studies of novel ofloxacin analogues as antimicrobial agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2011, 21, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S.E.; Iqbal, A.; Rahman, K.A.; Tahmeena, K. Thiosemicarbazone Complexes as Versatile Medicinal Chemistry Agents: A Review. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, V.Y.; Khatik, G.L.; Nair, V.A. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reaction of Nitrile Oxide to Thiocyanates: An Efficient and Eco-Friendly Synthesis of N -Aryl-2-((3-aryl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)thio)acetamides. Synthesis 2024, 56, 3173–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, V.Y.; Khatik, G.L.; Vijaya, B.S.; Nair, V.A. A Mild and Eco-friendly, One-pot Synthesis of 2-hydroxy-N-arylacetamides from 2-chloro-N-arylacetamides. Bentham Sci. Publ. 2024, 21, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, V.Y.; Khatik, G.L.; Kandaiah, S.; Nair, V.A. An Eco-Friendly, Multicomponent Reaction for 2-(5-Amino-4-cyano-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-aryl Acetamides: A Fine Tunable Push-Pull Chromophore With Photoelectrochemical Properties. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202405781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Khan, H.; Khan, M.; Abusharha, A.; Serdaroğlu, G.; Daglia, M. In Silico, SwissADME, and DFT Studies of Newly Synthesized Oxindole Derivatives Followed by Antioxidant Studies. J. Chem. 2023, 2023, 5553913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morak-Młodawska, B.; Jeleń, M.; Martula, E.; Korlacki, R. Study of Lipophilicity and ADME Properties of 1,9-Diazaphenothiazines with Anticancer Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.D.Y.; Terry, D.B.; Smith, L.H. In Vitro and In Vivo Assessment of ADME and PK Properties During Lead Selection and Lead Optimization-Guidelines, Benchmarks and Rules of Thumb Flow Chart of a Two-Tier Approach for In Vitro and In Vivo Analysis. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326710/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Murty, M.S.; Ram, K.R.; Rao, R.V.; Yadav, J.S.; Rao, J.V.; Velatooru, L.R. Synthesis of New S-alkylated-3-mercapto-1,2,4-triazole Derivatives Bearing Cyclic Amine Moiety as Potent Anticancer Agents. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2012, 9, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.B.; Wang, P.-Y.; Fang, Z.-M.; Wang, J.-J.; Guo, D.-X.; Ji, J.; Zhou, X.; Qi, P.-Y.; Liu, L.-W.; Yang, S. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 1,2,4-Triazole Thioethers as Both Potential Virulence Factor Inhibitors against Plant Bacterial Diseases and Agricultural Antiviral Agents against Tobacco Mosaic Virus Infections. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15108–15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calam, T.T. Analytical application of the poly(1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol) modified gold electrode for high-sensitive voltammetric determination of catechol in tap and lake water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 99, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozien, Z.A.; El-Mahdy, A.F.M.; Ali, L.S.A.; Markeb, A.A.; El-Sherief, H.A.H. One-Pot Synthesis of Some New s-Triazole Derivatives and Their Potential Application for Water Decontamination. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25574–25584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpun, Y.; Polishchuk, N. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of S-substituted derivatives of 1,2,4-triazol-3-thiol. Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 31, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Duan, H.; Qin, Q.; Teng, Z.; Gan, F.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, X. Advances in Oral Drug Delivery Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, J.N.; Gorman, S.P.; Gilmore, B.F. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.M.A.; Webber, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Ogbolu, D.O.; Piddock, L.J.V. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Plésiat, P.; Nikaido, H. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 337–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Manaia, C.; Merlin, C.; Schwartz, T.; Dagot, C.; Ploy, M.C.; Michael, I.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 447, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F.; Martínez, J.L.; Cantón, R. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaia, C.M.; Rocha, J.; Scaccia, N.; Marano, R.; Radu, E.; Biancullo, F.; Cerqueira, F.; Fortunato, G.; Iakovides, I.C.; Zammit, I.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in wastewater treatment plants: Tackling the black box. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riyadi, P.H.; Romadhon; Sari, I.D.; A Kurniasih, R.; Agustini, T.W.; Swastawati, F.; E Herawati, V.; A Tanod, W. SwissADME predictions of pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness properties of small molecules present in Spirulina platensis. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eloff, J.N. A sensitive and quick microplate method to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration of plant extracts for bacteria. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, T.; Boakye, Y.D.; Agyare, C. Antimicrobial Activities and Time-Kill Kinetics of Extracts of Selected Ghanaian Mushrooms. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 4534350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meerloo, J.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Cloos, J. Cell sensitivity assays: The MTT assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 731, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, L. Cell Viability Assays Assay Guidance Manual. 2004. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvents | Bases | Time (h) | Temp (°C) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | DCM | K2CO3 | 3 | RT | 60 |

| 2 | THF | K2CO3 | 3 | 60 | 65 |

| 3 | 1,4 Dioxane | K2CO3 | 3 | 80 | 68 |

| 4 | ACN | K2CO3 | 2 | 80 | 74 |

| 5 | Toluene | K2CO3 | 3 | 100 | 55 |

| 6 | DMF | K2CO3 | 1.5 | 100 | 75 |

| 7 | DMSO | K2CO3 | 1.5 | 100 | 78 |

| 8 | IPA | K2CO3 | 1 | 80 | 80 |

| 9 | MeOH | K2CO3 | 1 | 60 | 84 |

| 10 | EtOH | NaHCO3 | 0.75 | 80 | 83 |

| 11 | EtOH | Na2CO3 | 0.75 | 80 | 80 |

| 12 | EtOH | KtOBu | 1 | 80 | 72 |

| 13 | EtOH | K2CO3 | 0.25 | 80 | 90 |

| 14 | EtOH | TEA | 2 | 80 | 65 |

| 15 | EtOH | DIPEA | 2 | 80 | 68 |

| 16 | EtOH | K2CO3 | 2 | RT | 80 |

| 17 | EtOH | K2CO3 | 1 | 50 | 82 |

|  |  |

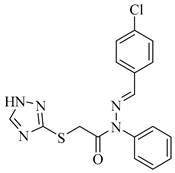

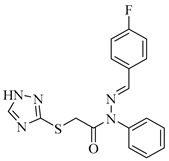

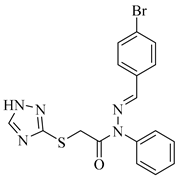

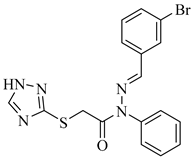

| 4a 93% | 4b 90% | 4c 90% |

|  |  |

| 4d 89% | 4e 92% | 4f 90% |

|  |  |

| 4g 88% | 4h 90% | 4i 91% |

|  |  |

| 4j 90% | 4k 90% | 4l 90% |

|  | |

| 4m 89% | 4n 88% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

S., A.; V., B.S.; G., A.A.; P. C., P.M.; Melge, A.R.; Madhavan, A.; Nair, B.G.; Kumar, G.; Nair, V.A.; Babu, P. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel 2-((1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide as Potential Antimicrobial Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412078

S. A, V. BS, G. AA, P. C. PM, Melge AR, Madhavan A, Nair BG, Kumar G, Nair VA, Babu P. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel 2-((1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide as Potential Antimicrobial Agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412078

Chicago/Turabian StyleS., Athul, Bhuvaneshwari S. V., Avani Anu G., Parvathi Mohanan P. C., Anu R. Melge, Aravind Madhavan, Bipin G. Nair, Geetha Kumar, Vipin A. Nair, and Pradeesh Babu. 2025. "Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel 2-((1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide as Potential Antimicrobial Agents" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412078

APA StyleS., A., V., B. S., G., A. A., P. C., P. M., Melge, A. R., Madhavan, A., Nair, B. G., Kumar, G., Nair, V. A., & Babu, P. (2025). Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel 2-((1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl)thio)-N-benzylidene-N-phenylacetohydrazide as Potential Antimicrobial Agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412078