1,2,3-Triazolo-Bridged Click Coupling of Pinane-Based Azidodiol Enantiomers with Pyrimidine- and Purine-Based Building Blocks: Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antimicrobial Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

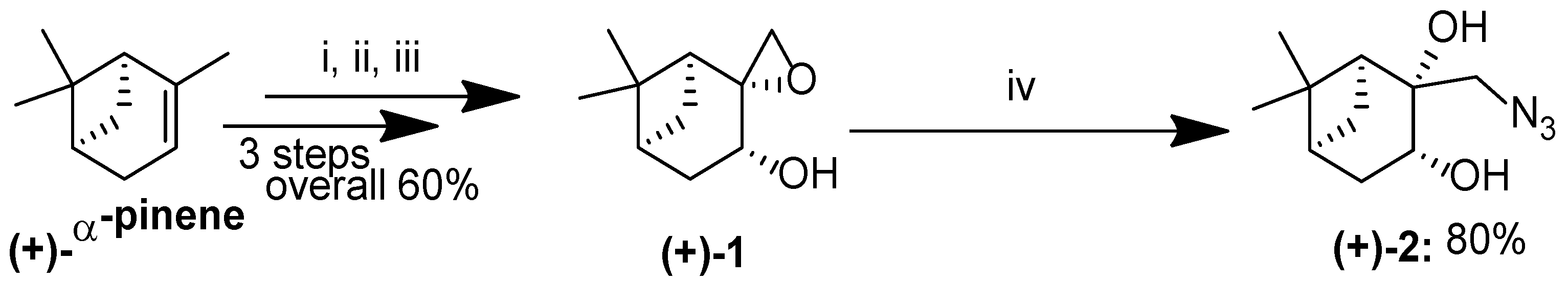

2.1. Synthesis of Pinan-Based Azides

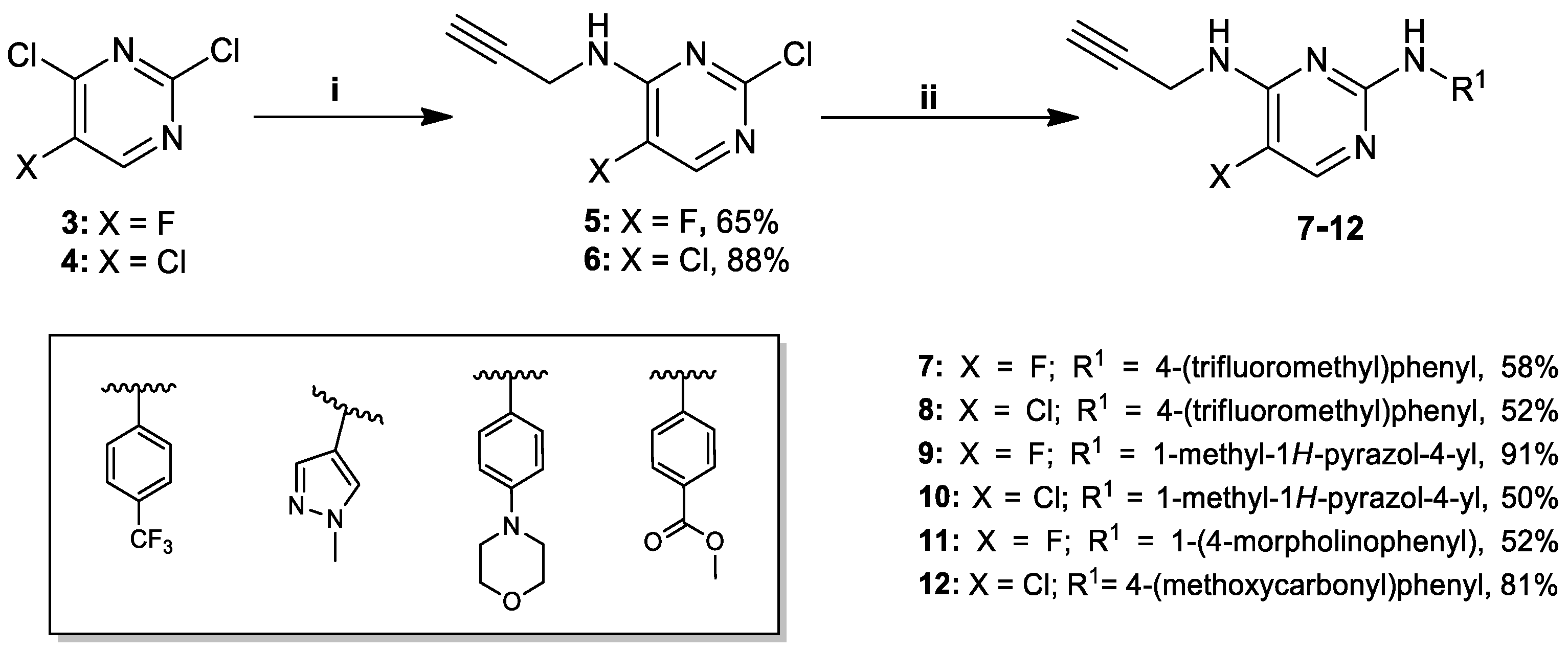

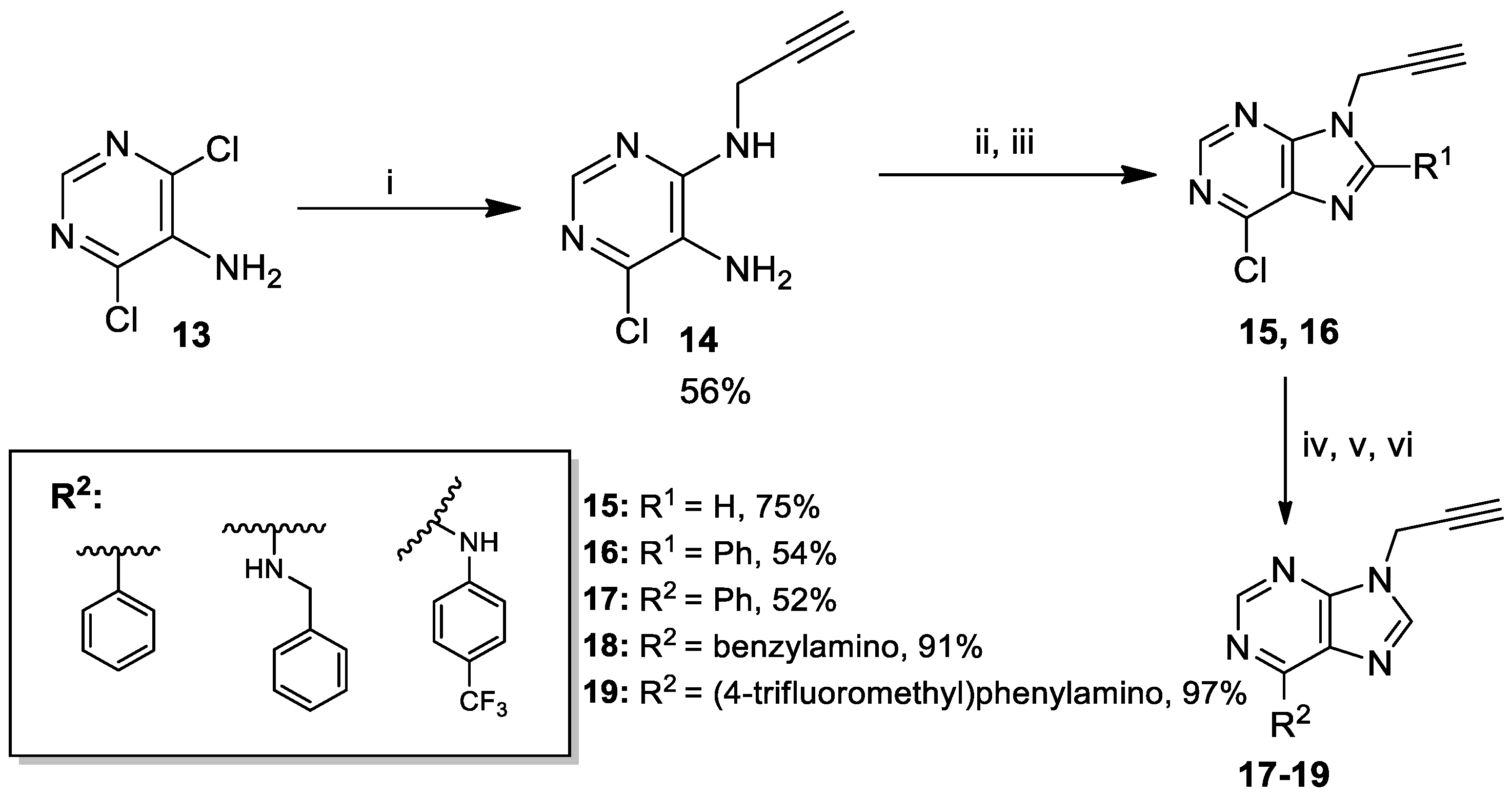

2.2. Synthesis of Key-Intermediate Alkynes

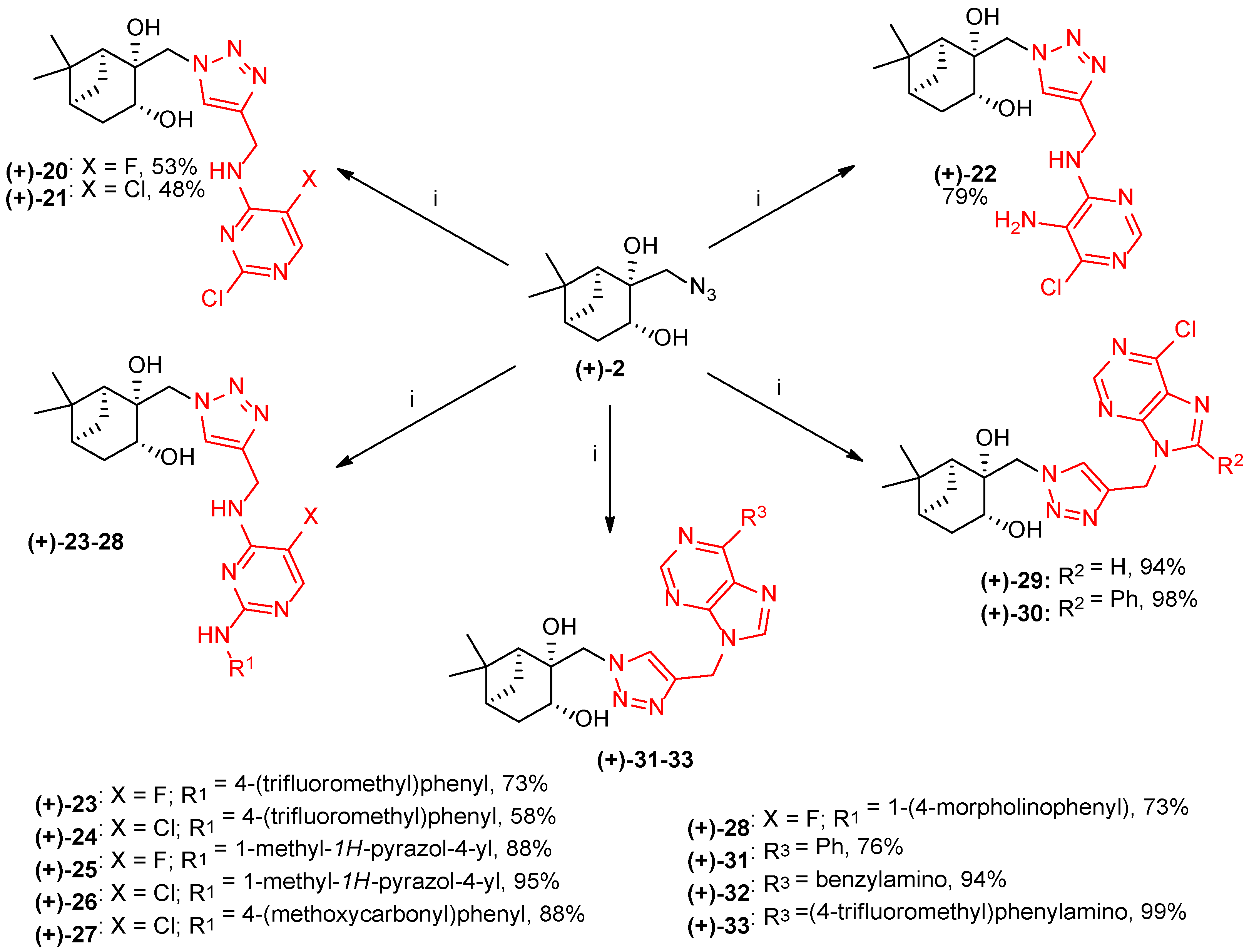

2.3. Coupling of the Pinane Moiety with Alkyne-Functionalized Heterocycles via Click Reaction

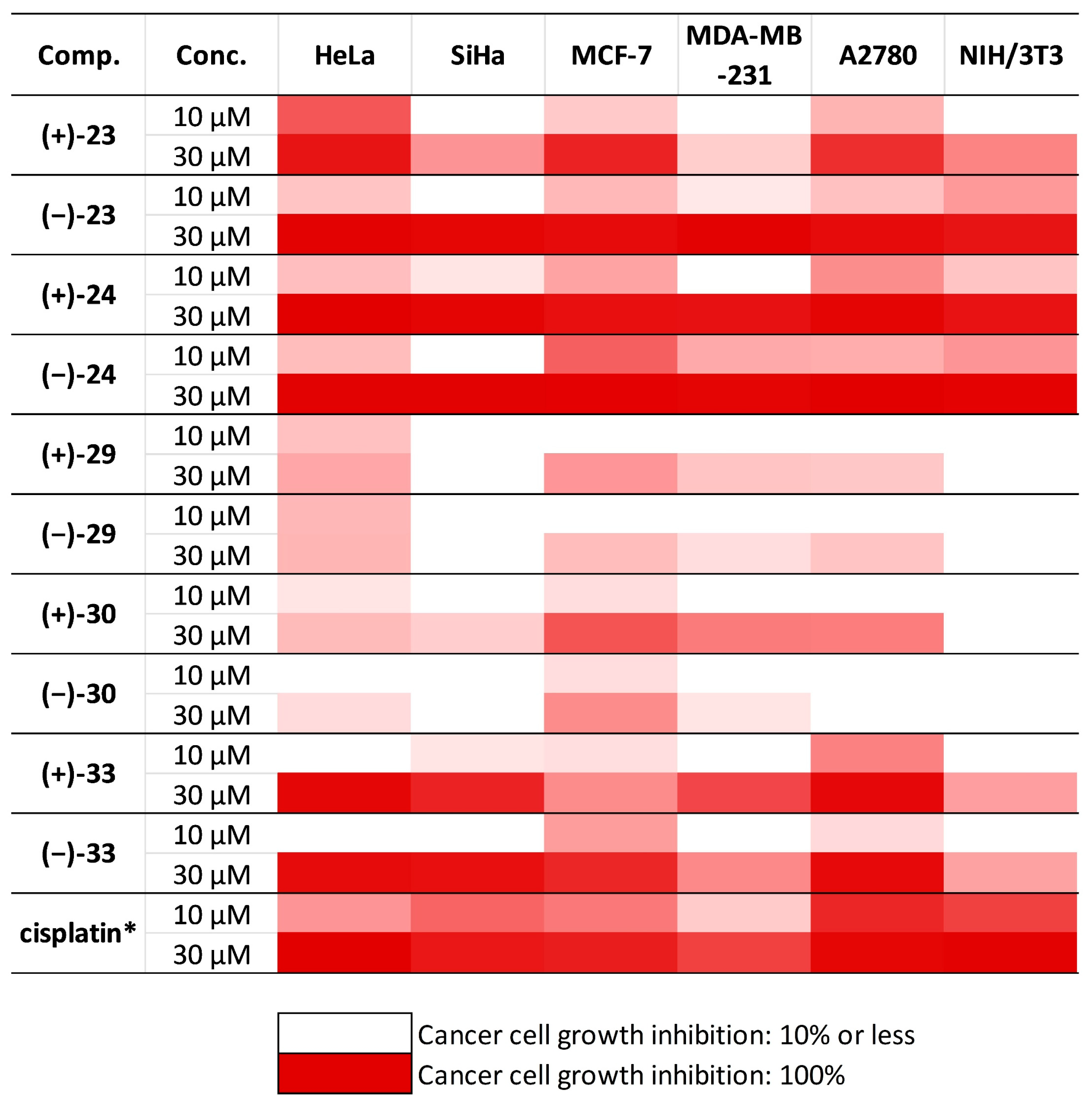

2.4. In Vitro Antiproliferative Studies of Pinane-Based Diaminopyrimidines and Structure–Activity Relationship

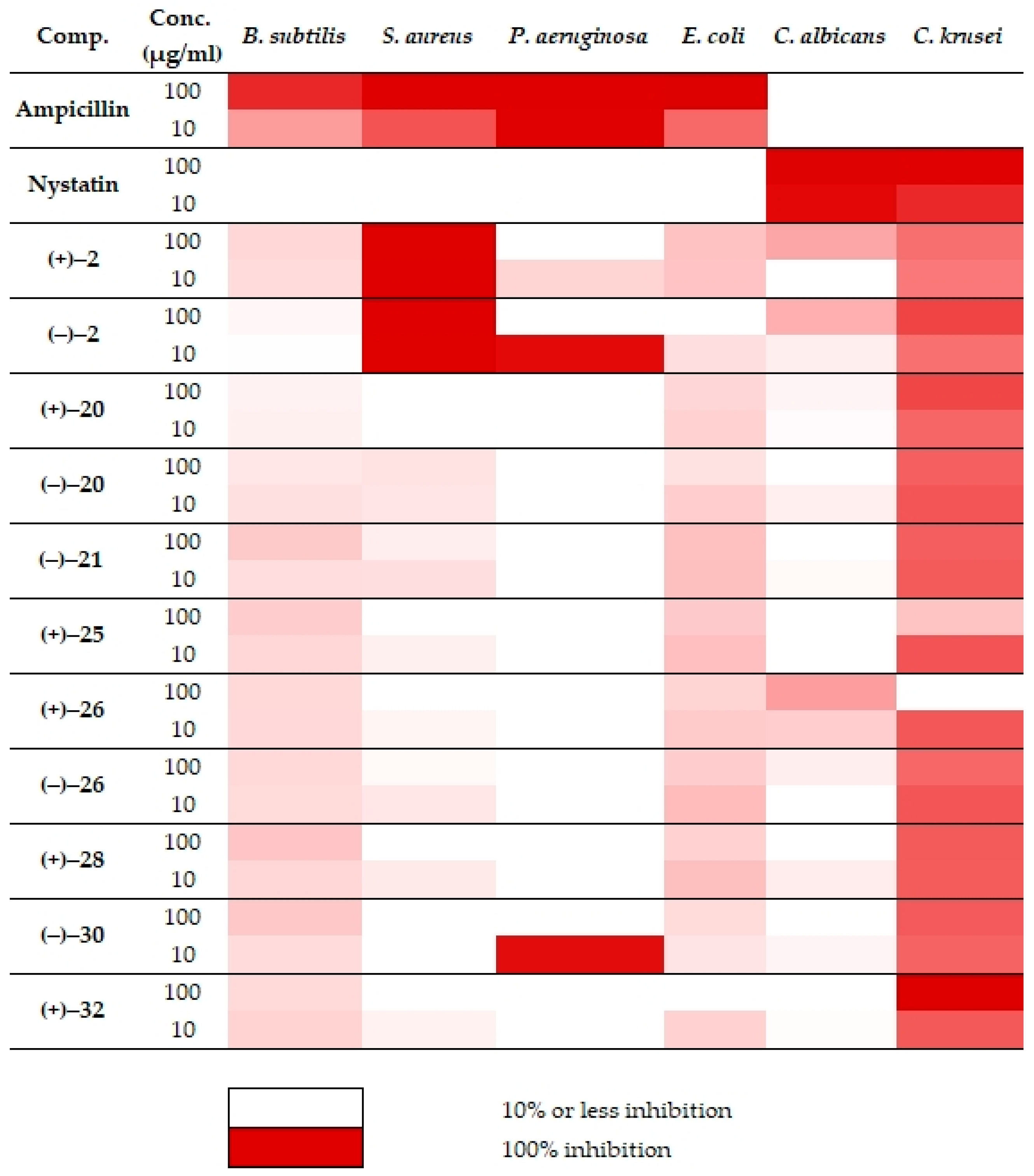

2.5. In Vitro Studies of Antibacterial Effects of 4-Amino- and 2,4-Diaminopyrimidine and Purine Derivatives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

3.2. Starting Materials

3.3. Synthesis of New Compounds

3.3.1. 6-Chloro-8-phenyl-9-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-9H-purine 16

3.3.2. N-Benzyl-9-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-9H-purin-6-amine 18

3.3.3. 9-(Prop-2-yn-1-yl)-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-9H-purin-6-amine 19

3.4. General Procedure for Preparation of 1,2,3-Triazols by Click Reaction (20–33)

3.4.1. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((2-Chloro-5-fluoropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo [3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-20

3.4.2. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((2,5-Dichloropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-21

3.4.3. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Amino-6-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-22

3.4.4. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Fluoro-2-((4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-23

3.4.5. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Chloro-2-((4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-24

3.4.6. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Fluoro-2-((1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-25

3.4.7. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Chloro-2-((1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-26

3.4.8. Methyl 4-((5-chloro-4-(((1-(((1S,2R,3R,5S)-2,3-dihydroxy-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-2-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)amino)pyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzoate (+)-27

3.4.9. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-(((5-Fluoro-2-((4-morpholinophenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-28

3.4.10. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-((6-Chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-29

3.4.11. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-((6-Chloro-8-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-30

3.4.12. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-6,6-Dimethyl-2-((4-((6-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-31

3.4.13. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-2-((4-((6-(Benzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-32

3.4.14. (1S,2R,3R,5S)-6,6-Dimethyl-2-((4-((6-((4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)amino)-9H-purin-9-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane-2,3-diol (+)-33

3.5. Determination of Antiproliferative Effect

3.6. Antimicrobial Analyses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| THF | Tetrahydrofurane |

| DCM | Dichlormethane |

| mCPBA | meta-Chloroperbenzoic acid |

| MW | Microwave |

| TEOF | Triethyl orthoformate |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| CuAAC | Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition |

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Global Cancer Burden Growing, Amidst Mounting Need for Services. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, M.; Le, T.M.; Huynh, T.; Szekeres, A.; Nagy, V.; Zupkó, I.; Szakonyi, Z. Divergent Synthesis, Antiproliferative and Antimicrobial Studies of 1,3-Aminoalcohol and 3-Amino-1,2-Diol Based Diaminopyrimidines. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwihura, R.J.; Ogungbe, I.V. The pinene scaffold: Its occurrence, chemistry, synthetic utility, and pharmacological importance. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 11346–11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonda, T.; Balázs, A.; Tóth, G.; Fülöp, F.; Szakonyi, Z. Stereoselective synthesis and transformations of pinane-based 1,3-diaminoalcohols. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 2638–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csillag, K.; Németh, L.; Martinek, T.A.; Szakonyi, Z.; Fülöp, F. Stereoselective synthesis of pinane-type tridentate aminodiols and their application in the enantioselective addition of diethylzinc to benzaldehyde. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2012, 23, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Chan, P.; Cohen, D.T.; Khawam, F.; Gibbons, S.; Snyder-Leiby, T.; Dickstein, E.; Rai, P.K.; Watal, G. Synthesis, Antimicrobial Evaluation, and Structure–Activity Relationship of α-Pinene Derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3548–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanglikar, G.; Kumar Tengli, A. A critical review on purine and pyrimidine heterocyclic derivatives and their designed molecules in Cancer. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerru, N.; Gummidi, L.; Maddila, S.; Gangu, K.K.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. A Review on Recent Advances in Nitrogen-Containing Molecules and Their Biological Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, H.R.; Martin, M.P.; Luo, Y.; Pireddu, R.; Yang, H.; Gevariya, H.; Ozcan, S.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Kendig, R.; Rodriguez, M.; et al. Development of o-Chlorophenyl Substituted Pyrimidines as Exceptionally Potent Aurora Kinase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7392–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomović Pavlović, K.; Kocić, G.; Šmelcerović, A. Myt1 kinase inhibitors—Insight into structural features, offering potential frameworks. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 391, 110901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, M.; Sankhe, K.; Bhandare, R.R.; Edis, Z.; Bloukh, S.H.; Khan, T.A. Synthetic Strategies of Pyrimidine-Based Scaffolds as Aurora Kinase and Polo-like Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2021, 26, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibi, M.; Qureshi, N.A.; Sadiq, A.; Farooq, U.; Hassan, A.; Shaheen, N.; Asghar, I.; Umer, D.; Ullah, A.; Khan, F.A.; et al. Exploring the ability of dihydropyrimidine-5-carboxamide and 5-benzyl-2,4-diaminopyrimidine-based analogues for the selective inhibition of L. major dihydrofolate reductase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, W.A. Inhibitors of F1F0-ATP synthase enzymes for the treatment of tuberculosis and cancer. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nammalwar, B.; Bunce, R.A. Recent Advances in Pyrimidine-Based Drugs. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Behera, B.; Purohit, C.S. Scaffolds of purine privilege for biological cytotoxic targets: A review. Pharm. Chem. J. 2023, 57, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Z. Purine Scaffold in Agents for Cancer Treatment. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 18170–18183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçbilek, M.; Ateş-Alagöz, Z.; Altanlar, N.; Karayel, A.; Özbey, S. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of some new substituted purine derivatives. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depp, D.; Sebők, N.R.; Szekeres, A.; Szakonyi, Z. Stereoselective Synthesis and Antimicrobial Studies of Allo-Gibberic Acid-Based 2,4-Diaminopyrimidine Chimeras. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szakonyi, Z.; Fülöp, F. Carbocyclic nucleosides from enantiomeric, α-pinane-based aminodiols. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2010, 21, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakonyi, Z.; Hetényi, A.; Fülöp, F. Synthesis and application of monoterpene-based chiral aminodiols. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, X.; Lv, Y.; Hao, Z.; Tang, L.; Li, K.; Zhao, B.; Fan, Z. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel Isothiazole-Purines as a Pyruvate Kinase-Based Fungicidal Lead Compound. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 9461–9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-X.; Xie, M.-S.; Zhao, G.-F.; Qu, G.-R.; Guo, H.-M. Synthesis of Chiral Cyclopropyl Carbocyclic Purine Nucleosides via Asymmetric Intramolecular Cyclopropanations Catalyzed by a Chiral Ruthenium(II) Complex. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 3627–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khdar, Z.A.; Le, T.M.; Schelz, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Szakonyi, Z. Aminodiols, aminotetraols and 1,2,3-triazoles based on allo-gibberic acid: Stereoselective syntheses and antiproliferative activities. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 36698–36712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.; Cornejo, M.A.; Hoang, T.T.; Lewis, J.S.; Zeglis, B.M. Click Chemistry and Radiochemistry: An Update. Bioconjugate Chem. 2023, 34, 1925–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Gu, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, B.; Jin, W.; Li, J.; Ma, P.; Xu, H.; Hou, W. Strategic application of CuAAC click chemistry in the modification of natural products for anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2023, 9, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, C.; Ho, D.-K.; Hamed, M.M.; Abdelsamie, A.S.; Röhrig, T.; Herr, C.; Kany, A.M.; Rox, K.; Schmelz, S.; Siebenbürger, L.; et al. New PqsR Inverse Agonist Potentiates Tobramycin Efficacy to Eradicate Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, R.; Vasava, M.; Abhirami, R.B.; Karsharma, M. Recent advances in triazole synthesis via click chemistry and their pharmacological applications: A review. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 112, 129927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, X.; Kong, F.; Chen, P.; Pan, G. Improving cellular uptake of therapeutic entities through interaction with components of cell membrane. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madikonda, A.K.; Ajayakumar, A.; Nadendla, S.; Banothu, J.; Muripiti, V. Esterase-responsive nanoparticles (ERN): A targeted approach for drug/gene delivery exploits. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2024, 116, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De O. Torres, N.M.P.; Cardoso, G.D.A.; Silva, H.; de Freitas, R.P.; Alves, R.B. New purine-triazole hybrids as potential anti-breast cancer agents: Synthesis, antiproliferative activity, and ADMET in silico study. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 1816–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Burcevs, A.; Sebris, A.; Traskovskis, K.; Chu, H.-W.; Chang, H.-T.; Jovaišaitė, J.; Juršėnas, S.; Turks, M.; Novosjolova, I. Synthesis of Fluorescent C–C Bonded Triazole-Purine Conjugates. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 34, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, Y.K.; Gupta, V.; Singh, S. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of pyrimidine based derivatives. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 7, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, F.; Safa, Y.; Sultan, M.; Bibi, I.; Rehman, F.; Shah, S.I. Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of azides and its derivatives. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 280, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Radha, A.; Kaur, H.; Malik, S.; Stanzin, J.; Komal; Singh, B.; Baliyan, D.; Singh, K.N. Versatile Benzophenone Derivatives: Broad Spectrum Antibiotics, Antioxidants, Anticancer Agents and Fe(III) Chemosensor. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 39, e7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, M.I.; Langtry, H.D. Zidovudine: An update of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 1993, 46, 515–578, Erratum in Drugs 1993, 46, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, M.; Aksakal, E.; Özgeriş, F.; Ozgeris, B.; Gormez, A. Biological Evaluation of Azide Derivative as Antibacterial and Anticancer Agents. Nat. Prod. Biotechnol. 2022, 2, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comp. | Conc. (μM) | Growth Inhibition (%) ± SEM 1,2 Calculated IC50 (μM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | SiHa | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | A2780 | NIH/3T3 | ||

| (+)-23 | 10 | 66.04 ± 1.27 | – | 21.67 ± 2.45 | – | 30.45 ± 1.86 | – |

| 30 | 89.81 ± 1.34 | 42.81 ± 2.03 | 84.53 ± 1.25 | 20.30 ± 1.89 | 80.44 ± 1.57 | 48.65 ± 2.058 | |

| IC50 | 7.54 | >30 | 18.59 | >30 | 14.79 | >30 | |

| (−)-23 | 10 | 23.39 ± 2.39 | – | 28.48 ± 2.42 | 10.18 ± 1.94 | 25.34 ± 1.77 | 40.61 ± 2.06 |

| 30 | 96.09 ± 1.82 | 94.73 ± 2.01 | 93.28 ± 1.02 | 96.44 ± 2.98 | 93.19 ± 1.53 | 76.30 ± 3.295 | |

| IC50 | 13.68 | 19.85 | 11.77 | 15.78 | 13.80 | 11.71 | |

| (+)-24 | 10 | 26.01 ± 2.80 | 10.89 ± 1.84 | 36.81 ± 3.59 | – | 45.43 ± 1.76 | 23.49 ± 1.60 |

| 30 | 100.94 ± 0.47 | 95.32 ± 1.86 | 91.45 ± 0.90 | 90.81 ± 1.47 | 95.25 ± 1.30 | 90.34 ± 1.79 | |

| IC50 | 11.06 | 16.21 | 16.15 | 20.93 | 11.86 | 14.64 | |

| (−)-24 | 10 | 26.61 ± 1.36 | – | 62.86 ± 0.97 | 34.81 ± 0.70 | 32.98 ± 2.64 | 42.45 ± 0.77 |

| 30 | 97.56 ± 0.76 | 97.59 ± 1.28 | 98.24 ± 0.47 | 95.68 ± 2.10 | 101.38 ± 0.72 | 96.77 ± 1.22 | |

| IC50 | 12.76 | 18.90 | 8.79 | 11.69 | 11.06 | 10.51 | |

| Comp. 1,2 | Conc. (µg/mL) | Growth Inhibition (%) 2 ± SEM 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | E. coli | C. albicans | C. krusei | ||

| Amp | 100 | 84.7 ± 7.0 | 100.0 ± 3.5 | 100.0 ± 3.2 | 100.4 ± 8.6 | – | – |

| 10 | 40.1 ± 6.3 | 68.48 ± 2.2 | 99.7 ± 3.8 | 60.2 ± 8.3 | – | – | |

| Nyst | 100 | – | – | – | – | 99.0 ± 2.2 | 99.0 ± 2.1 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | 95.9 ± 16.0 | 84.3 ± 20.0 | |

| (+)-2 | 100 | 16.6 ±4.1 | 101.3 ± 7.0 | 0 | 24.9 ± 2.6 | 36.8 ± 12.4 | 58.0 ± 13.4 |

| 10 | 14.6 ± 6.4 | 101.2 ± 8.5 | 17.7 ± 6.5 | 24.4 ± 2.4 | 0 | 54.4 ± 13.9 | |

| (−)-2 | 100 | 3.3 ± 6.8 | 101.1 ± 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 32.8 ±1.5 | 73.9 ± 10.7 |

| 10 | 0.6 ± 6.0 | 101.6 ± 5.1 | 95.1± 29.6 | 13.7 ± 3.1 | 7.5 ± 21.1 | 57.8 ± 10.5 | |

| (+)-20 | 100 | 5.2 ± 8.5 | 0 | 0 | 17.1 ± 7.1 | 4.2 ± 8.7 | 73.1 ± 3.4 |

| 10 | 6.2 ± 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 18.5 ± 2.6 | 2.0 ± 16.3 | 61.4 ± 1.8 | |

| (−)-20 | 100 | 10.5 ± 7.1 | 12.1 ± 4.9 | 0 | 12.7 ± 7.2 | 0 | 64.1 ± 20.1 |

| 10 | 12.8 ± 9.2 | 10.8 ± 5.8 | 0 | 20.2 ± 2.8 | 7.1 ± 9.7 | 67.5 ± 18.0 | |

| (−)-21 | 100 | 22.2 ± 2.1 | 7.6 ± 2.5 | 0 | 26.3 ± 2.2 | 0 | 64.5 ± 10.1 |

| 10 | 14.3 ± 7.4 | 13.6 ± 5.2 | 0 | 26.6 ± 8.0 | 2.7 ± 4.5 | 66.2 ± 11.8 | |

| (+)-25 | 100 | 20.7 ± 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 22.0 ± 3.7 | 0 | 24.3 ± 5.8 |

| 10 | 16.5 ± 7.9 | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 0 | 26.3 ± 2.5 | 0 | 68.3 ± 8.4 | |

| (+)-26 | 100 | 16.2 ± 8.6 | 0 | 0 | 17.8 ± 4.6 | 39.7 ± 3.8 | 0 |

| 10 | 15.6 ± 9.7 | 4.5 ± 3.5 | 0 | 21.8 ± 5.3 | 20.1 ± 9.1 | 66.8 ± 4.3 | |

| (−)-26 | 100 | 16.2 ± 7.7 | 2.6 ± 6.6 | 0 | 20.5 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 3.4 | 60.7 ± 5 |

| 10 | 14.9 ± 8.1 | 10.4 ± 3.2 | 0 | 27.8 ± 9.5 | 0 | 67.5 ± 15.2 | |

| (+)-28 | 100 | 23.6 ± 5.3 | 0 | 0 | 18.5 ± 5.7 | 0 | 66.2 ± 10.4 |

| 10 | 16.5 ± 4.6 | 9.1 ± 3.2 | 0 | 26.6 ± 6.5 | 7.9 ± 13.7 | 65.3 ± 6.2 | |

| (−)-30 | 100 | 23.1 ± 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 15.52 ± 4.80 | 0 | 66.4 ± 2.4 |

| 10 | 14.7 ± 5.5 | 0 | 94.0 ± 28.7 | 11.21 ± 6.53 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 62.5 ± 12.6 | |

| (+)-32 | 100 | 15.9 ± 5.2 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 101.7 ± 16.1 |

| 10 | 18.2 ± 4.2 | 5.3 ± 4.6 | 0 | 18.5 ± 5.4 | 1.4 ± 3.6 | 66.5 ± 9.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Depp, D.; Tari, K.; Szekeres, A.; Kovács, A.; Zupkó, I.; Szakonyi, Z. 1,2,3-Triazolo-Bridged Click Coupling of Pinane-Based Azidodiol Enantiomers with Pyrimidine- and Purine-Based Building Blocks: Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antimicrobial Evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311705

Depp D, Tari K, Szekeres A, Kovács A, Zupkó I, Szakonyi Z. 1,2,3-Triazolo-Bridged Click Coupling of Pinane-Based Azidodiol Enantiomers with Pyrimidine- and Purine-Based Building Blocks: Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antimicrobial Evaluation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311705

Chicago/Turabian StyleDepp, Dima, Kitti Tari, András Szekeres, Adriána Kovács, István Zupkó, and Zsolt Szakonyi. 2025. "1,2,3-Triazolo-Bridged Click Coupling of Pinane-Based Azidodiol Enantiomers with Pyrimidine- and Purine-Based Building Blocks: Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antimicrobial Evaluation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311705

APA StyleDepp, D., Tari, K., Szekeres, A., Kovács, A., Zupkó, I., & Szakonyi, Z. (2025). 1,2,3-Triazolo-Bridged Click Coupling of Pinane-Based Azidodiol Enantiomers with Pyrimidine- and Purine-Based Building Blocks: Synthesis, Antiproliferative, and Antimicrobial Evaluation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311705