Does Podoplanin (PDPN) Reflect the Involvement of the Immunological System in Coronary Artery Disease Risk? A Single-Center Prospective Analysis

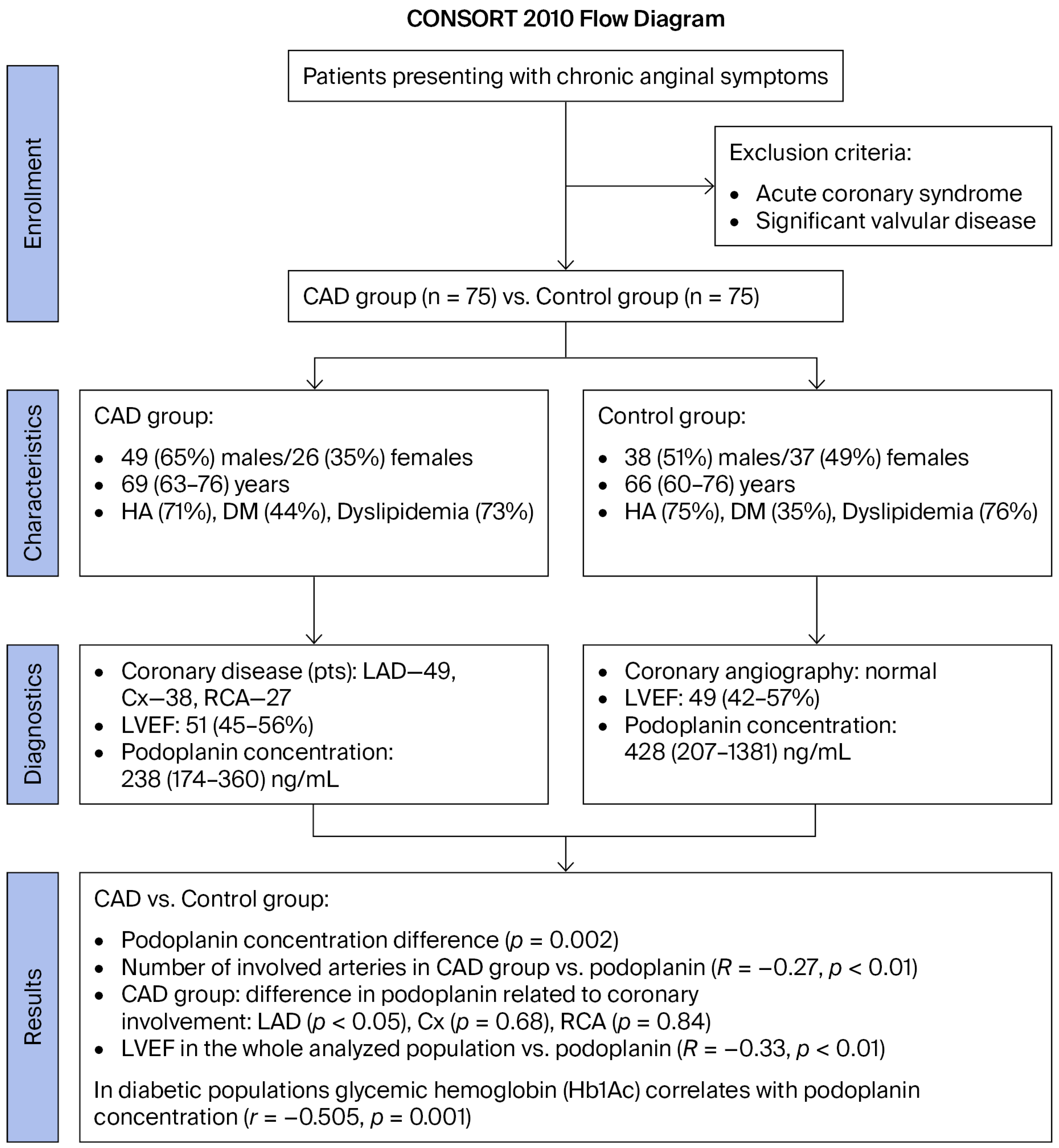

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biochemical Analysis

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheok, Y.Y.; Tan, G.M.Y.; Chan, Y.T.; Abdullah, S.; Looi, C.Y.; Wong, W.F. Podoplanin and its multifaceted roles in mammalian developmental program. Cells Dev. 2024, 180, 203943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, D.; Huang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Podoplanin: Its roles and functions in neurological diseases and brain cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 964973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Agriantonis, G.; Shafaee, Z.; Twelker, K.; Bhatia, N.D.; Kuschner, Z.; Arnold, M.; Agcon, A.; Dave, J.; Mestre, J.; et al. Role of Podoplanin (PDPN) in Advancing the Progression and Metastasis of Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers 2024, 16, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, D.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Cao, Y.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, X. A Role of the Podoplanin-CLEC-2 Axis in Promoting Inflammatory Response After Ischemic Stroke in Mice. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki-Inoue, K. Roles of the CLEC-2-podoplanin interaction in tumor progression. Platelets 2018, 29, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Yu, J.; Xu, W.; Gao, J.; Lv, X.; Wen, Z. The Role of Podoplanin in the Immune System and Inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 3561–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, X.; Shi, C.; Ren, X.; Ma, X.; He, Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. PDPN positive CAFs contribute to HER2 positive breast cancer resistance to trastuzumab by inhibiting antibody-dependent NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Drug Resist. Updat. 2023, 68, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugge, H.; Downer, M.K.; Carlsson, J.; Bowden, M.; Davidsson, S.; Mucci, L.A.; Fall, K.; Andersson, S.O.; Andrén, O. Circulating inflammation markers and prostate cancer. Prostate 2019, 79, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz-Krzywiec, P.; Martín-Pérez, R.; Ehling, M.; García-Caballero, M.; Pinioti, S.; Pretto, S.; Kroes, R.; Aldeni, C.; Di Matteo, M.; Prenen, H.; et al. Podoplanin-Expressing Macrophages Promote Lymphangiogenesis and Lymphoinvasion in Breast Cancer. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 917–936.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Sun, W. Galectin-8 involves in arthritic condylar bone loss via podoplanin/AKT/ERK axis-mediated inflammatory lymphangiogenesis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonente, D.; Bianchi, L.; De Salvo, R.; Nicoletti, C.; De Benedetto, E.; Bacci, T.; Bini, L.; Inzalaco, G.; Franci, L.; Chiariello, M.; et al. Co-Expression of Podoplanin and CD44 in Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy Epiretinal Membranes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Wang, Q.; An, J.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Long, Q.; Xiao, L.; Guan, X.; Liu, J. CD44 Glycosylation as a Therapeutic Target in Oncology. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 883831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, M.; Watanabe, N.; Ito, M.; Pastan, I.; Koizumi, M.; Matsusaka, T. C-type lectin-like receptor (CLEC)-2, the ligand of podoplanin, induces morphological changes in podocytes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki-Inoue, K.; Tsukiji, N. A role of platelet C-type lectin-like receptor-2 and its ligand podoplanin in vascular biology. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2024, 31, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, P.; Koczwarska-Maciejek, D.; Kamiński, K.; Gąsior, Z.; Kosior, D.A.; Styczkiewicz, M.; Kubica, A.; Rajzer, M.; Charkiewicz-Szeremeta, K.; Dąbek, J.; et al. Implementation of cardiovascular prevention guidelines in clinical practice. Results from the POLASPIRE II survey. Kardiol. Pol. 2025, 83, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Gutaj, P.; Plewa, S.; Spasenenko, I.; Krasińska, B.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Kowalczyk, D.; Krasiński, Z.; Grywalska, E.; Rahnama-Hezavah, M.; et al. Lower Sphingomyelin SM 42:1 Plasma Level in Coronary Artery Disease-Preliminary Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Gutaj, P.; Plewa, S.; Spasenenko, I.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Krasińska, B.; Tykarski, A.; Krasińska-Plachta, A.; Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak, Ł.; Krasiński, Z.; et al. Obesity and acylcarnitine derivates interplay with coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Gutaj, P.; Plewa, S.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Spasenenko, I.; Krasińska, B.; Tykarski, A.; Filipiak, K.J.; Pakuła-Iwańska, M.; Krasiński, Z.; et al. The Lower Concentration of Plasma Acetyl-Carnitine in Epicardial Artery Disease-A Preliminary Report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, K.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Nishihira, K.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Shibata, Y.; Ozaki, Y.; Asada, Y. Podoplanin expression in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of human aortas. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, e70–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X. Podoplanin: A potential therapeutic target for thrombotic diseases. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1118843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzimek, A.; Dziedzic, E.A.; Beck, J.; Kochman, W. Correlations Between Acute Coronary Syndrome and Novel Inflammatory Markers (Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index, Systemic Inflammation Response Index, and Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation) in Patients with and without Diabetes or Prediabetes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xin, S.; Gu, R.; Zheng, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Dong, H. Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers Related to Oxidative Stress and Macrophage Ferroptosis in Atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8917947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanowicz, T.; Michalak, M.; Olasińska-Wiśniewska, A.; Rodzki, M.; Krasińska, A.; Perek, B.; Krasiński, Z.; Jemielity, M. Monocyte/Lymphocyte Ratio and MCHC as Predictors of Collateral Carotid Artery Disease-Preliminary Report. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado-Genovés, G.; Herrero-Cervera, A.; Vinué, Á.; Martín-Vañó, S.; Aguilar-Ballester, M.; Taberner-Cortés, A.; Jiménez-Martí, E.; Martínez-Hervás, S.; González-Navarro, H. Light deficiency in Apoe−/− mice increases atheroma plaque size and vulnerability by modulating local immunity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, X. Investigating the landscape of immune-related genes and immunophenotypes in atherosclerosis: A bioinformatics Mendelian randomization study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1871, 167649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa-Matysek, J.; Urbanowicz, T. High-intensity statin therapy and its anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombogenic properties related to neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, S.; Hari-Gupta, Y.; Cantoral-Rebordinos, J.A.; Martinez, V.G.; Horsnell, H.L.; Benjamin, A.C.; Cinti, I.; Jovancheva, M.; Shewring, D.; Nguyen, N.; et al. Lymph node fibroblast phenotypes and immune crosstalk regulated by podoplanin activity. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupenova, M.; Livada, A.C.; Morrell, C.N. Platelet and Megakaryocyte Roles in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Mu, G.; Cui, Y.; Xiang, Q. C-type lectin-like receptor 2: Roles and drug target. Thromb. J. 2024, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Wang, L.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wu, F.; You, T.; Ren, L.; Xia, L.; Ruan, C.; et al. CLEC-2-dependent platelet subendothelial accumulation by flow disturbance contributes to atherogenesis in mice. Theranostics 2021, 11, 9791–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, M.; Garikipati, V.N.S.; de Lucia, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Truongcao, M.M.; Lucchese, A.M.; Roy, R.; Benedict, C.; Goukassian, D.A.; et al. Podoplanin neutralization improves cardiac remodeling and function after acute myocardial infarction. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e126967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Qian, L.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhao, Y. Podoplanin neutralization reduces thrombo-inflammation in experimental ischemic stroke by inhibiting interferon/caspase-1/GSDMD in microglia. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki-Inoue, K.; Osada, M.; Ozaki, Y. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of interaction between C-type lectin-like receptor 2 and podoplanin: Partners from in utero to adulthood. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.; Wilting, J. Molecules That Have Rarely Been Studied in Lymphatic Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovd, A.-M.K.; Nayar, S.; Smith, C.G.; Kanapathippillai, P.; Iannizzotto, V.; Barone, F.; Fenton, K.A.; Pedersen, H.L. Podoplanin expressing macrophages and their involvement in tertiary lymphoid structures in mouse models of Sjögren’s disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1455238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xia, L. Emerging roles of podoplanin in vascular development and homeostasis. Front. Med. 2015, 9, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, G.K.; Chwalba, A.; Basek, A.; Cieślar, G.; Pawlas, N. Glycated Hemoglobin and Cardiovascular Disease in Patients Without Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, Y.; Kitahara, S.; Funabashi, S.; Makino, H.; Matsubara, M.; Matsuo, M.; Omura-Ohata, Y.; Koezuka, R.; Tochiya, M.; Tamanaha, T.; et al. The effect of continuous glucose monitoring-guided glycemic control on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: The OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2023, 37, 108592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Roles of Podoplanin in Malignant Progression of Tumor. Cells 2022, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, N.; Assaf, M.; Diab, N.; Soliman, A.; Salah, E. Morphometric study of lymphangiogenesis in different lesions of psoriasis vulgaris with correlation to disease activity. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 3110–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitalo, K. The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P. The Role of Lymphangiogenesis in Coronary Atherosclerosis. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2022, 20, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukiji, N.; Suzuki-Inoue, K. Impact of Hemostasis on the Lymphatic System in Development and Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. Platelets as an inter-player between hyperlipidaemia and atherosclerosis. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 296, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zong, G.N.; Wu, H.; Zhang, K.Q. Podoplanin mediates the renoprotective effect of berberine on diabetic kidney disease in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Ni, C.; Cai, Z.; Qiu, S.; Li, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Podoplanin-TGF-β1 Autocrine Loop: Pivotal Regulator of Islet Stellate Cell Activation via Cell Deformation, Orchestrating Islet Fibrosis in Diabetes. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, F.; Jiang, X. Serum Podoplanin Levels as a Potential Biomarker for Diabetic Nephropathy Progression: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4701–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuschik, L.; Riabov, V.; Schmuttermaier, C.; Sevastyanova, T.; Weiss, C.; Klüter, H.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Hyperglycemia Induces Inflammatory Response of Human Macrophages to CD163-Mediated Scavenging of Hemoglobin-Haptoglobin Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.Y.; Lu, C.H.; Cheng, C.F.; Li, K.J.; Kuo, Y.M.; Wu, C.H.; Liu, C.H.; Hsieh, S.C.; Tsai, C.Y.; Yu, C.L. Advanced Glycation End-Products Acting as Immunomodulators for Chronic Inflammation, Inflammaging and Carcinogenesis in Patients with Diabetes and Immune-Related Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Masi, A.; De Simone, G.; Ciaccio, C.; D’Orso, S.; Coletta, M.; Ascenzi, P. Haptoglobin: From hemoglobin scavenging to human health. Mol. Asp. Med. 2020, 73, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konduracka, E.; Cieślik, G.; Małecki, M.T.; Gajos, G.; Siniarski, A.; Malinowski, K.P.; Kostkiewicz, M.; Mastalerz, L.; Nessler, J.; Piwowarska, W. Obstructive and nonobstructive coronary artery disease in long-lasting type 1 diabetes: A 7-year prospective cohort study. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2019, 129, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Lemberg, M.K.; Fluhrer, R. Proteolytic ectodomain shedding of membrane proteins in mammals-hardware, concepts, and recent developments. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakabe, K.; Omura, T.; Shibagaki, Y.; Mihara, E.; Homma, K.; Kato, Y.; Yoshimura, A.; Murakami, Y.; Takagi, J.; Hattori, S.; et al. Mechanistic insights into ectodomain shedding: Susceptibility of CADM1 adhesion molecule is determined by alternative splicing and O-glycosylation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Sheriff, L.; Hussain, M.T.; Webb, G.J.; Patten, D.A.; Shepherd, E.L.; Shaw, R.; Weston, C.J.; Haldar, D.; Bourke, S.; et al. The platelet receptor CLEC-2 blocks neutrophil mediated hepatic recovery in acetaminophen induced acute liver failure. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Jibi, A.; Basavaraj, V. Study of Podoplanin Expression in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Iran. J. Pathol. 2022, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | CAD Group n = 75 | Control Group n = 75 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years, median (Q1–Q3)) | 69 (63–76) | 66 (60–76) | 0.67 |

| Sex (male (%)/female (%)) | 49 (65)/26 (35) | 38 (51)/37 (49) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (median (Q1–Q3)) | 29.1 (26.2–31.2) | 28.7 (26.8–33.7) | 0.42 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Arterial hypertension (n (%)) | 53 (71) | 56 (75) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n (%)) | 33 (44) | 26 (35) | 0.09 |

| Dyslipidemia (n (%)) | 55 (73) | 57 (76) | 0.49 |

| Peripheral artery disease (n (%)) | 17 (23) | 12 (16) | 0.41 |

| COPD (n (%)) | 5 (7) | 8 (11) | 0.56 |

| Kidney dysfunction * (n (%)) | 7 (9) | 3 (4) | 0.20 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n (%)) | 7 (9) | 11 (15) | 0.53 |

| Pharmacotherapy | |||

| B-blockers (n (%)) | 73 (97) | 72 (96) | 1.00 |

| ACE-I (n (%)) | 43 (57) | 45 (60) | 0.87 |

| ARB (n (%)) | 10 (13) | 11 (15) | 1.00 |

| CCB (n (%)) | 14 (19) | 17 (23) | 0.68 |

| Diuretics (n (%)) | 23 (31) | 21 (28) | 0.86 |

| Aspirin (n (%)) | 75 (100) | 75 (100) | 1.00 |

| NOAC (n (%)) | 7 (9) | 11 (15) | 0.45 |

| SGLT2i (n (%)) | 13 (17) | 12 (16) | 1.00 |

| Statins (n (%)) | 55 (73) | 57 (76) | 0.85 |

| High-dose statin therapy (n (%)) | |||

| Esetimibe (n (%)) | 11 (15) | 10 (13) | 1.00 |

| Metformin (n (%)) | 33 (44) | 26 (35) | 0.32 |

| Parameters | CAD Group n = 75 | Control Group n = 75 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory results (median (Q1–Q3)) | |||

| 1. Peripheral blood analysis | |||

| White blood count (×109/dL) | 7.2 (5.9–7.9) | 7.0 (6.0–8.0) | 1.00 |

| Hemoglobin (mmol/dL) | 9.0 (8.3–9.6) | 8.7 (8.1–9.3) | 0.45 |

| Platelets (×109/dL) | 241 (209–272) | 227 (187–288) | 0.74 |

| 2. Kidney function tests | |||

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 65 (63–67) | 68 (62–77) | 0.16 |

| 3. Liver function tests | |||

| Alanine transaminase (IU/dL) | 25 (19–34) | 29 (19–44) | 0.46 |

| 4. Glycemic hemoglobin (Hb1Ac) (%) | 6.5 (5.9–7.0) | 6.1 (5.3–6.5) | 0.09 |

| 5. Lipidogram (mmol/L) | |||

| Total cholesterol | 153 (124–183) | 153 (123–181) | 0.92 |

| High-density lipoprotein | 46 (39–58) | 55 (44–74) | 0.08 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 73 (53–123) | 74 (50–111) | 0.84 |

| Triglycerides | 87 (63–173) | 76 (48–101) | 0.08 |

| PDPN serum concentration (ng/mL) | 238 (174–360) | 428 (207–1381) | 0.002 |

| Echocardiography on admission | |||

| Left ventricular diastolic diameter (mm) (median (Q1–Q3)) | 51 (45–56) | 49 (42–57) | 0.71 |

| Left atrium diameter (mm) (median (Q1–Q3)) | 38 (36–41) | 38 (35–45) | 0.88 |

| Interventricular septum (mm) (median (Q1–Q3)) | 11 (10–12) | 12 (11–13) | 0.013 |

| Mitral regurgitation (grade) (mean (SD)) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.47 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation (grade) (mean (SD)) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.88 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) (median (Q1–Q3)) | 56 (46–60) | 57 (48–62) | 0.55 |

| Coronary angiography results (n (%)) | <0.001 | ||

| 1—vessel disease | 25 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| 2—vessel disease | 25 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| 3—vessel disease | 25 (33) | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urbanowicz, T.; Rupa-Matysek, J.; Wojtasińska, E.; Krasińska, B.; Zieliński, M.; Grobelna, M.; Zawadzki, P.; Staniszewski, R.; Krasiński, Z.; Paszyńska, E.; et al. Does Podoplanin (PDPN) Reflect the Involvement of the Immunological System in Coronary Artery Disease Risk? A Single-Center Prospective Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412051

Urbanowicz T, Rupa-Matysek J, Wojtasińska E, Krasińska B, Zieliński M, Grobelna M, Zawadzki P, Staniszewski R, Krasiński Z, Paszyńska E, et al. Does Podoplanin (PDPN) Reflect the Involvement of the Immunological System in Coronary Artery Disease Risk? A Single-Center Prospective Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412051

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrbanowicz, Tomasz, Joanna Rupa-Matysek, Ewelina Wojtasińska, Beata Krasińska, Maciej Zieliński, Malwina Grobelna, Paweł Zawadzki, Ryszard Staniszewski, Zbigniew Krasiński, Elżbieta Paszyńska, and et al. 2025. "Does Podoplanin (PDPN) Reflect the Involvement of the Immunological System in Coronary Artery Disease Risk? A Single-Center Prospective Analysis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412051

APA StyleUrbanowicz, T., Rupa-Matysek, J., Wojtasińska, E., Krasińska, B., Zieliński, M., Grobelna, M., Zawadzki, P., Staniszewski, R., Krasiński, Z., Paszyńska, E., & Tykarski, A. (2025). Does Podoplanin (PDPN) Reflect the Involvement of the Immunological System in Coronary Artery Disease Risk? A Single-Center Prospective Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412051