From Genetic Engineering to Preclinical Safety: A Study on Recombinant Human Interferons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Purification and Determination of the Biological Potency of the Active Ingredients rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

2.1.1. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human Interferon Alpha rhIFNα-2b

2.1.2. In Vitro Biological Activity Assays of Purified rhIFNα-2b

Antiproliferative Activity of rhIFNα-2b

2.1.3. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human Interferon Gamma rhIFN-γ

2.1.4. In Vitro Biological Activity Assays of Purified rhIFN-γ

Antiproliferative Activity of rhIFN-γ

Immunomodulatory Activity of rhIFN-γ

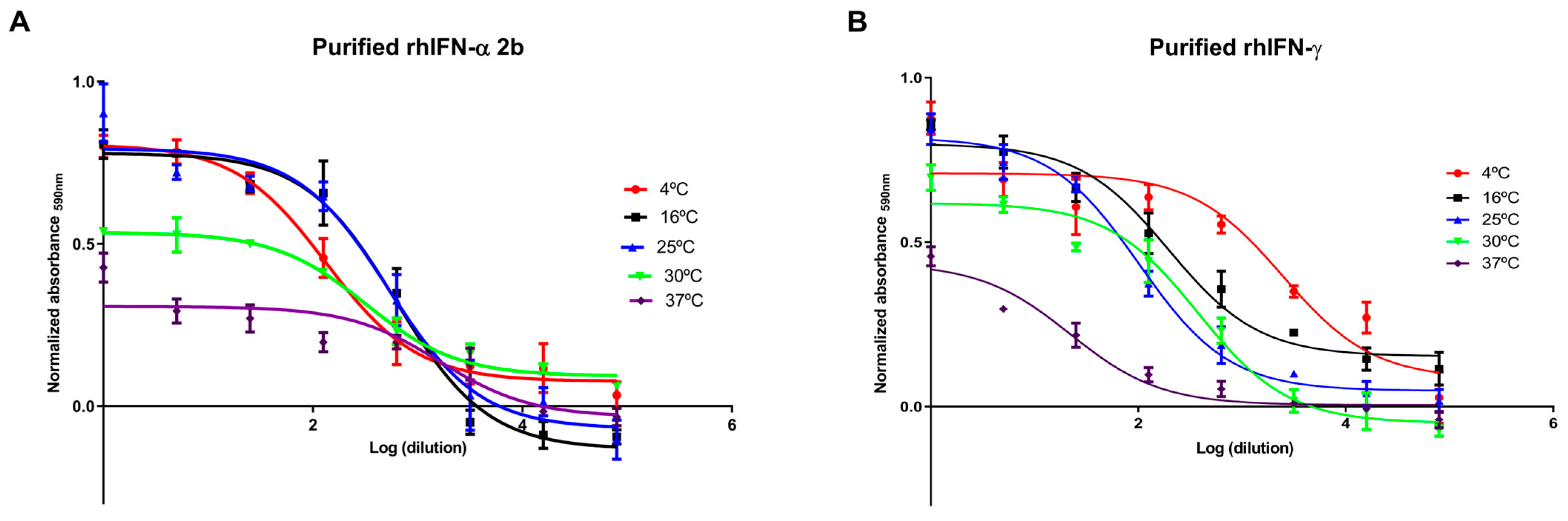

2.2. Stability Under Accelerated Conditions of rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

2.3. Endotoxin Analysis (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Test)

2.4. Animal Safety Studies with the Active Ingredients rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

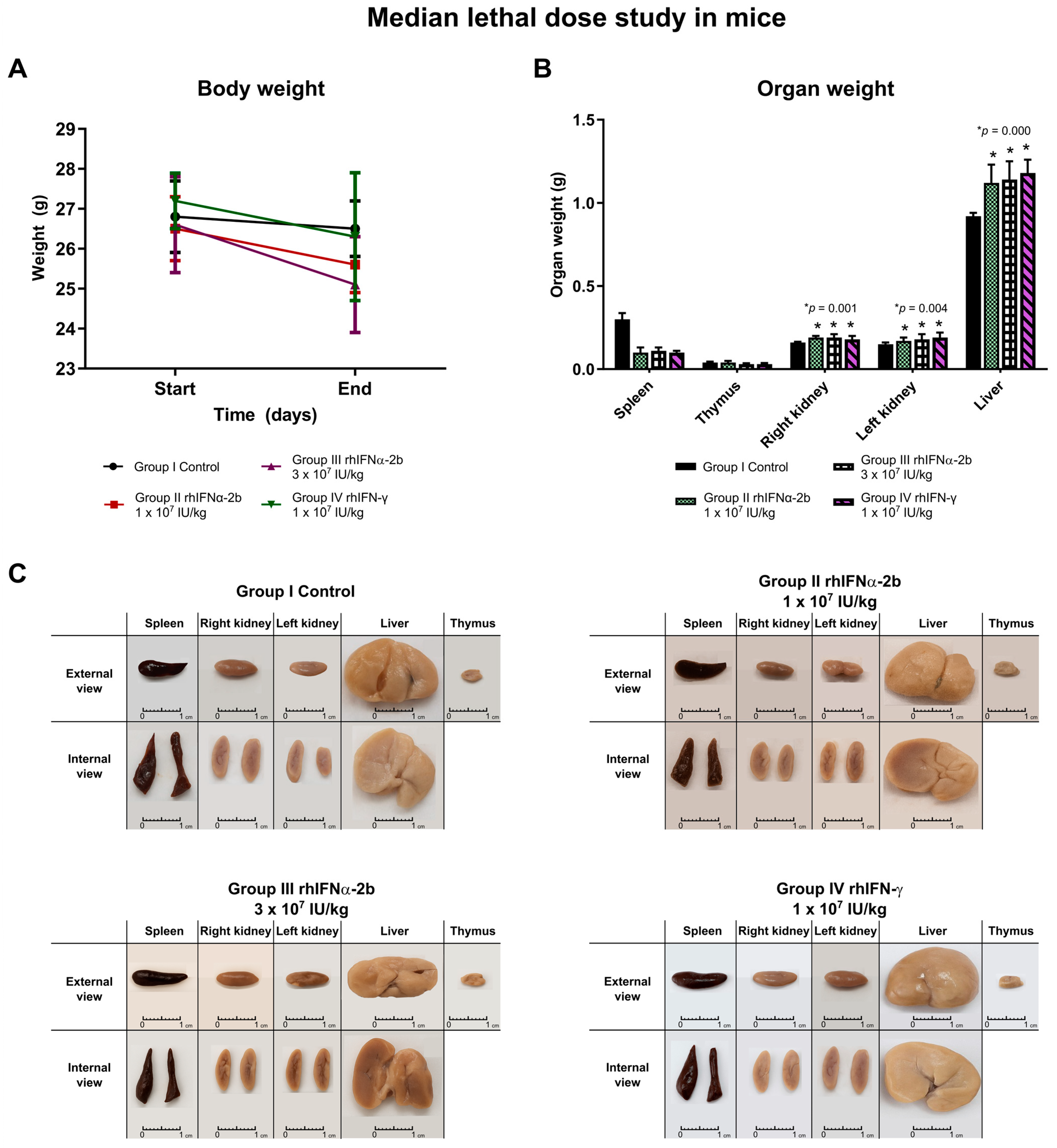

2.4.1. Median Lethal Dose Study with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ in Mice

- Study on organ weight post-necropsy. Macroscopic analysis:

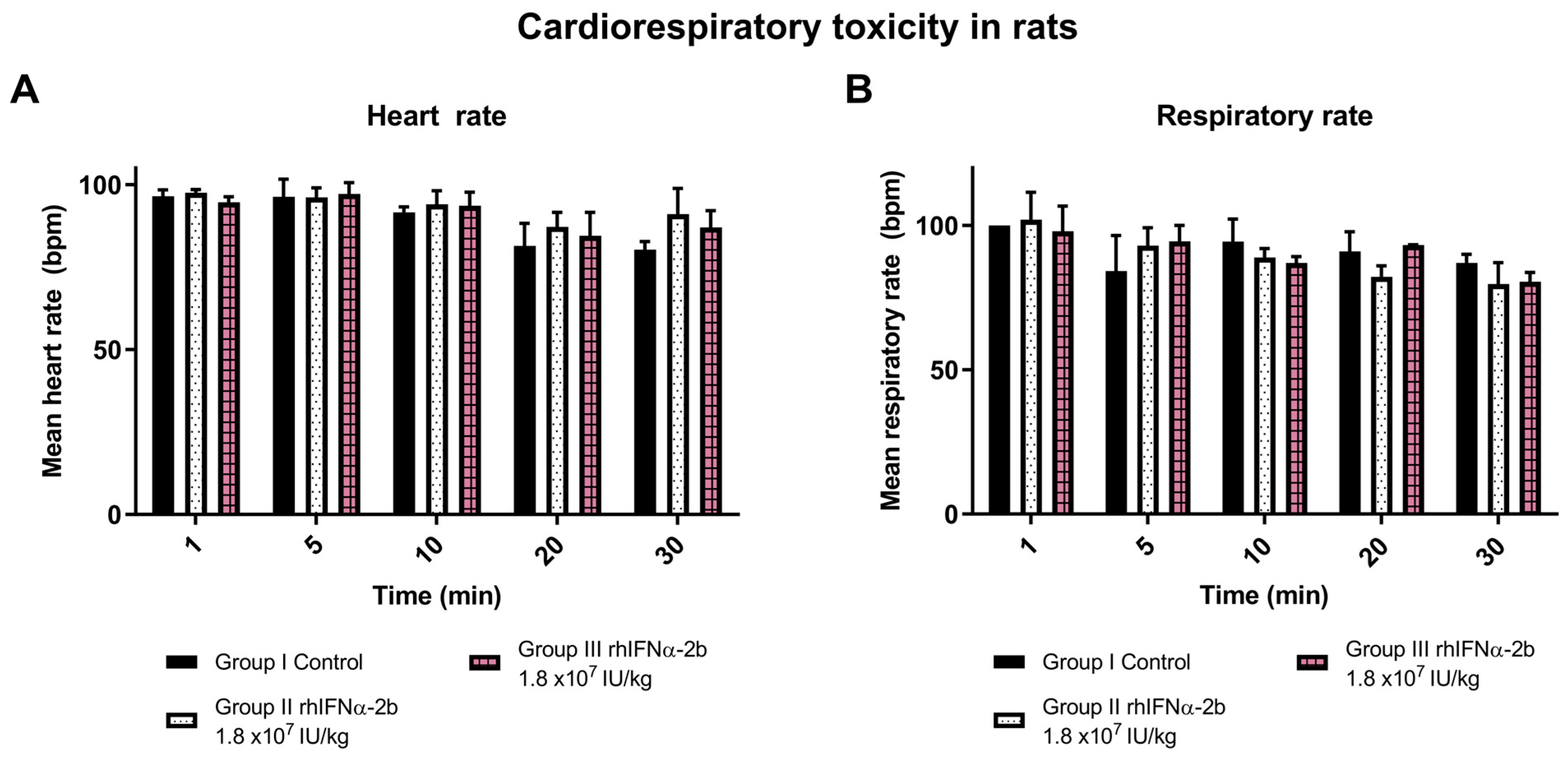

2.4.2. Cardiorespiratory Toxicity with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ in Rats

2.4.3. Subchronic Toxicity Assays with rhIFNα-2b in Rats

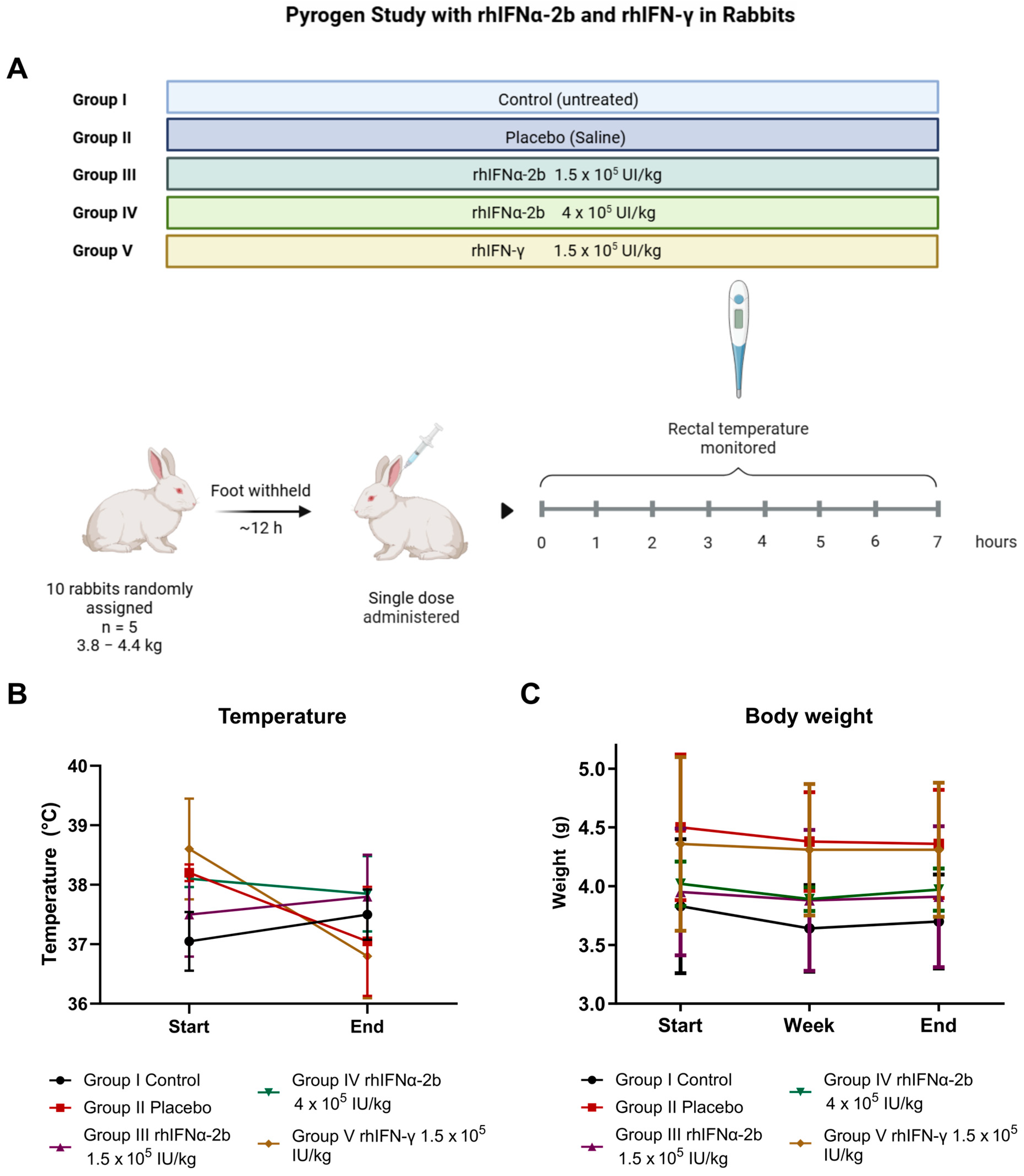

2.4.4. Pyrogen Study

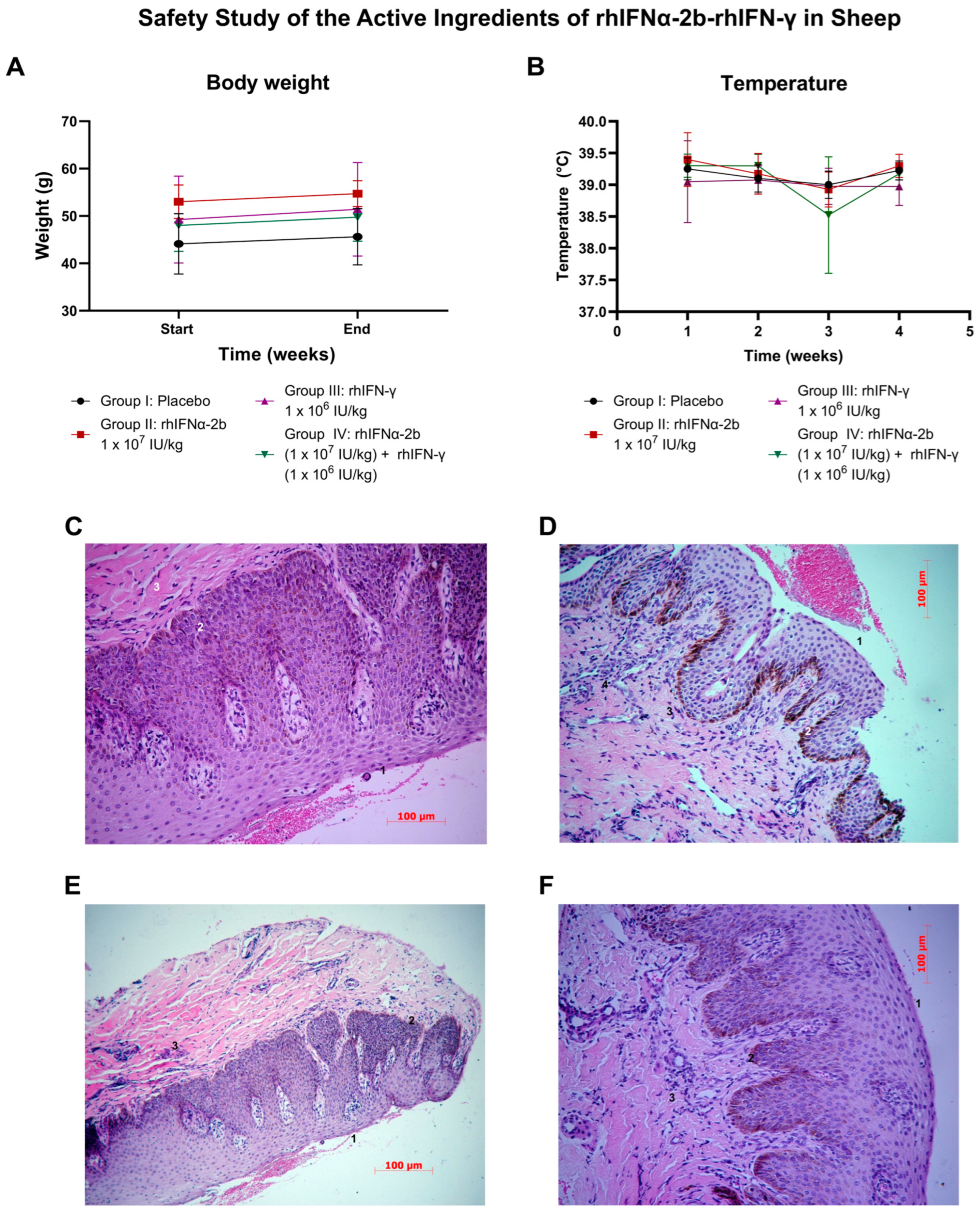

2.4.5. Safety Study of the Active Ingredients of rhIFNα-2b-rhIFN-γ in Sheep

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Plasmids

4.1.2. Bacteria and Cell Lines

4.1.3. Animals

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Purification and Determination of the Biological Potency of the Active Ingredients rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human Interferon Alpha rhIFNα-2b

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Human Interferon Gamma rhIFN-γ

4.2.2. In Vitro Biological Activity Assays

Antiproliferative Activity of Purified rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

Evaluation of the Immunoregulatory Activity of Purified rhIFN-γ

Stability Under Accelerated Conditions of Purified rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

Statistical Analysis of In Vitro Studies

- Antiproliferative activity of rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

- Immunoregulatory Activity of rhIFN-γ

4.2.3. Endotoxin Analysis (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Test)

4.2.4. Animal Safety Studies with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ

LD50 with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ in Mice

Cardiorespiratory Toxicity with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ in Rats

Subchronic Toxicity Studies with rhIFNα-2b in Rats

Pyrogen Study with rhIFNα-2b and rhIFN-γ in Rabbits

Mucosal Toxicity Study of Interferons in Sheep

- Experimental design:

Statistical Analysis of Animal Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zannikou, M.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Signaling by Type I Interferons in Immune Cells: Disease Consequences. Cancers 2024, 16, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.I.; Villacis-Aguirre, C.A.; Santiago Vispo, N.; Santiago Padilla, L.; Pedroso Santana, S.; Parra, N.C.; Alonso, J.R.T. Forms and Methods for Interferon’s Encapsulation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.C.; Sridhar, P.R.; Baldridge, M.T. Differential roles of interferons in innate responses to mucosal viral infections. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briukhovetska, D.; Dörr, J.; Endres, S.; Libby, P.; Dinarello, C.A.; Kobold, S. Interleukins in cancer: From biology to therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalskov, L.; Gad, H.H.; Hartmann, R. Viral recognition and the antiviral interferon response. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.S.; Lobo, G.S.; Pereira, P.; Freire, M.G.; Neves, M.C.; Pedro, A.Q. Interferon-Based Biopharmaceuticals: Overview on the Production, Purification, and Formulation. Vaccines 2021, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebeish, R.; Hamdy, E.; Al-Zoubi, O.; Habeeb, T.; Osailan, R.; El-Ayouty, Y. A Biotechnological Approach for the Production of Pharmaceutically Active Human Interferon-α from Raphanus sativus L. Plants. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, T.; Grubbe, W.S.; Nusbaum, R.J.; Mendoza, J.L. Recent and future perspectives on engineering interferons and other cytokines as therapeutics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.Y.; Gao, D.M.; Zhou, W.; Xia, B.B.; He, Z.Y.; Wu, B.; Jiang, M.Z.; Wang, M.L.; Zhao, J. Acute and Sub-chronic Toxicity Study of Recombinant Bovine Interferon Alpha in Rodents. J. Vet. Res. 2021, 65, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.-M.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhou, W.; Xia, B.-B.; Li, H.-Z.; Wang, M.-L.; Zhao, J. Inhibitory effects of recombinant porcine interferon-α on porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus infections in TGEV-seronegative piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 252, 108930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglan, A.M.; Albaradie, O.A.; Alsayegh, F.F.; Alharbi, H.M.; Samman, Y.M.; Jalal, M.M.; Saeedi, N.H.; Mahmoud, A.B.; Alkayyal, A.A. Preclinical efficacy of oncolytic VSV-IFNβ in treating cancer: A systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1085940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Ash, A.; Sarkar, K. Interferon alpha-2b (IFNα2b) in precision oncology: Innovations in delivery and combinatorial immunotherapy. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 273, 156113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, K.M.; Sheehy, T.L.; Wilson, J.T. Chemical and Biomolecular Strategies for STING Pathway Activation in Cancer Immunotherapy. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5977–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Lee, H.K. Engineering interferons for cancer immunotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaescu, G.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Filip, R.; Bleotu, C.; Ditu, L.M.; Constantin, M.; Cristian, R.-E.; Grigore, R.; Bertesteanu, S.V.; Bertesteanu, G.; et al. Role of interferons in the antiviral battle: From virus-host crosstalk to prophylactic and therapeutic potential in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1273604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizoz, B.; Ishii, K.J. Type I and II interferons toward ideal vaccine and immunotherapy. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardo, S.; Di Pietro, M.; Bozzuto, G.; Fracella, M.; Bitossi, C.; Molinari, A.; Scagnolari, C.; Antonelli, G.; Sessa, R. Interferon-ε as potential inhibitor of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 185, 106427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jaggi, U.; Katsumata, M.; Ghiasi, H. The importance of IFNα2A (Roferon-A) in HSV-1 latency and T cell exhaustion in ocularly infected mice. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, B.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Y. Investigation into the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of recombinant human interferon alfa-2b vaginal suppository following process optimization in chinese rhesus macaque. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohan, S.L.; Hendin, B.A.; Reder, A.T.; Smoot, K.; Avila, R.; Mendoza, J.P.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Interferons and Multiple Sclerosis: Lessons from 25 Years of Clinical and Real-World Experience with Intramuscular Interferon Beta-1a (Avonex). CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nitto, C.; Gilardoni, E.; Mock, J.; Nadal, L.; Weiss, T.; Weller, M.; Seehusen, F.; Libbra, C.; Puca, E.; Neri, D.; et al. An Engineered IFNγ-Antibody Fusion Protein with Improved Tumor-Homing Properties. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo Reyes, S.O.; González Garay, A.; González Bobadilla, N.Y.; Rivera Lizárraga, D.A.; Madrigal Paz, A.C.; Medina-Torres, E.A.; Álvarez Cardona, A.; Galindo Ortega, J.L.; Solís Galicia, C.; Espinosa-Padilla, S.E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Interferon-Gamma in Chronic Granulomatous Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, J.; Vázquez-Blomquist, D.; Bringas, R.; Fernandez-de-Cossio, J.; Palenzuela, D.; Novoa, L.I.; Bello-Rivero, I. A co-formulation of interferons alpha2b and gamma distinctively targets cell cycle in the glioblastoma-derived cell line U-87MG. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo Alonso, J.R.; Ramos Gómez, T.I.; Sandoval Sandoval, F.A.; Gómez Gaete, C.P.; Manrique, V.; Arcia, E.L.; Cabezas Ávila, O.I.; Sanchez Ramos, O. Una Formulación Antiviral que Tiene una Presentación Núcleo-Cubierta de Liberación Controlada, que Encapsula Combinaciones de Interferones Alfa (rhIFNα-2b) e Interferón Gamma (rhIFN-γ) Recombinantes. CL Patent Application No. CL 2021003420 A1, 20 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, S.K.; Yang, Q.; Tong, X.; Wang, L.X. Exploring a combined Escherichia coli-based glycosylation and in vitro transglycosylation approach for expression of glycosylated interferon alpha. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2021, 33, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookhoo, J.R.V.; Schiffman, Z.; Ambagala, A.; Kobasa, D.; Pardee, K.; Babiuk, S. Protein Expression Platforms and the Challenges of Viral Antigen Production. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, E.; Rowan, N.; Garvey, M. Bioprocessing and the Production of Antiviral Biologics in the Prevention and Treatment of Viral Infectious Disease. Vaccines 2023, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleitas-Salazar, N.; Lamazares, E.; Pedroso-Santana, S.; Kappes, T.; Pérez-Alonso, A.; Hidalgo, Á.; Altamirano, C.; Sánchez, O.; Fernández, K.; Toledo, J.R. Long-term release of bioactive interferon-alpha from PLGA-chitosan microparticles: In vitro and in vivo studies. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 143, 213167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volosnikova, E.A.; Esina, T.I.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Volkova, N.V.; Gogina, Y.S.; Tereshchenko, T.A.; Danilenko, E.D. The Production of Soluble Human Gamma Interferon in the Escherichia coli Expression System with a Decrease in Cultivation Temperature. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2023, 59, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronopoulou, S.; Tsochantaridis, I.; Tokamani, M.; Kokkinopliti, K.D.; Tsomakidis, P.; Giannakakis, A.; Galanis, A.; Pappa, A.; Sandaltzopoulos, R. Expression and purification of human interferon alpha 2a (IFNα2a) in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2023, 211, 106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuvanshi, V.; Yadav, P.; Ali, S. Interferon production by Viral, Bacterial & Yeast system: A comparative overview in 2023. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 120, 110340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Gao, W. Cytokine conjugates to elastin-like polypeptides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 190, 114541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G.; Kim, T.; Hong, S.; Chu, J.; Kang, J.E.; Park, H.G.; Choi, J.Y.; Song, K.; Rha, S.Y.; Lee, S.; et al. Antibody-Based Targeting of Interferon-Beta-1a Mutein in HER2-Positive Cancer Enhances Antitumor Effects Through Immune Responses and Direct Cell Killing. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 608774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, N.; Condos, R.; Shebuski, R. Inhaled interferon gamma as a therapeutic agent in interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2022, 161, A239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumhefner, R.W.; Leng, M. Standard Dose Weekly Intramuscular Beta Interferon-1a May Be Inadequate for Some Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A 19-Year Clinical Experience Using Twice a Week Dosage. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.; Cardoso, A.P.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Serre, K.; Oliveira, M.J. Interferon-Gamma at the Crossroads of Tumor Immune Surveillance or Evasion. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, K.C.; Miljkovic, M.D.; Waldmann, T.A. Cytokines in the Treatment of Cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019, 39, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, R.N.; Ferreira, L.; Pace, F.H.L. Health-related quality of life and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C with therapy with direct-acting antivirals agents interferon-free. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deadame de Figueiredo Nicolete, L.; Vladimiro Cunha, C.; Paulo Tavanez, J.; Tomazini Pinto, M.; Strazza Rodrigues, E.; Kashima, S.; Tadeu Covas, D.; Miguel Villalobos-Salcedo, J.; Nicolete, R. Hepatitis delta: In vitro evaluation of cytotoxicity and cytokines involved in PEG-IFN therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 91, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Dai, C.; Wu, W.; Xu, J.; Jin, W.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Q. The safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of nebulized pegylated interferon α-2b in healthy adults: A randomized phase 1 trial. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2025, 26, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianevski, A.; Yao, R.; Zusinaite, E.; Lello, L.S.; Wang, S.; Jo, E.; Yang, J.; Ravlo, E.; Wang, W.; Lysvand, H.; et al. Synergistic Interferon-Alpha-Based Combinations for Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Viral Infections. Viruses 2021, 13, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, I.S.; Hammond, P.T.; Irvine, D.J. Engineering Strategies for Immunomodulatory Cytokine Therapies—Challenges and Clinical Progress. Adv. Ther. 2021, 4, 2100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, M.; Chen, S.H. Instability Challenges and Stabilization Strategies of Pharmaceutical Proteins. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A. Solid lipid nanoparticles: A multidimensional drug delivery system. In Nanoscience in Medicine Vol. 1; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 249–295. [Google Scholar]

- Santhanakrishnan, K.R.; Koilpillai, J.; Narayanasamy, D. PEGylation in Pharmaceutical Development: Current Status and Emerging Trends in Macromolecular and Immunotherapeutic Drugs. Cureus 2024, 16, e66669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkbid, E.; Cree, D.E.; Bradford, L.; Zhang, W. Biodegradable Alternatives to Plastic in Medical Equipment: Current State, Challenges, and the Future. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdieniezhnykh, N.; Lykhova, O.; Borshchevskiy, G.; Kruglov, Y.; Borshchevska, M. Evaluation of the duration of new nasal drug interferon α-2b activity in an experimental model system. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioele, G.; Chieffallo, M.; Occhiuzzi, M.A.; De Luca, M.; Garofalo, A.; Ragno, G.; Grande, F. Anticancer Drugs: Recent Strategies to Improve Stability Profile, Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishani, A.; Meschaninova, M.I.; Zenkova, M.A.; Chernolovskaya, E.L. The Impact of Chemical Modifications on the Interferon-Inducing and Antiproliferative Activity of Short Double-Stranded Immunostimulating RNA. Molecules 2024, 29, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougal, M.B.; Boys, I.N.; De La Cruz-Rivera, P.; Schoggins, J.W. Evolution of the interferon response: Lessons from ISGs of diverse mammals. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 53, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, L.; Shi, J.; Li, J.; Wen, Y.; Gu, G.; Cui, J.; Feng, C.; Jiang, M.; Fan, Q.; et al. Interferon stimulated immune profile changes in a humanized mouse model of HBV infection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weerd, N.A.; Kurowska, A.K.; Mendoza, J.L.; Schreiber, G. Structure–function of type I and III interferons. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2024, 86, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ashuo, A.; Hao, M.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Liu, J.; Hua, T.; Fang, Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; et al. An extracellular humanized IFNAR immunocompetent mouse model for analyses of human interferon alpha and subtypes. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2287681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beers, M.M.C.; Sauerborn, M.; Gilli, F.; Brinks, V.; Schellekens, H.; Jiskoot, W. Aggregated Recombinant Human Interferon Beta Induces Antibodies but No Memory in Immune-Tolerant Transgenic Mice. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 1812–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappos, L.; Clanet, M.; Sandberg-Wollheim, M.; Radue, E.W.; Hartung, H.P.; Hohlfeld, R.; Xu, J.; Bennett, D.; Sandrock, A.; Goelz, S.; et al. Neutralizing antibodies and efficacy of interferon β-1a. Neurology 2005, 65, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Hui, E.K.; Lu, J.Z.; Pardridge, W.M. IgG-enzyme fusion protein: Pharmacokinetics and anti-drug antibody response in rhesus monkeys. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, L.J.; Bailey, J.; Cassotta, M.; Herrmann, K.; Pistollato, F. Poor Translatability of Biomedical Research Using Animals —A Narrative Review. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2023, 51, 102–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, F.R.; Cavagnaro, J.; McKeever, K.; Ryan, P.C.; Schutten, M.M.; Vahle, J.; Weinbauer, G.F.; Marrer-Berger, E.; Black, L.E. Safety testing of monoclonal antibodies in non-human primates: Case studies highlighting their impact on human risk assessment. MAbs 2018, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, P.; Kister, B.; Fendt, R.; Köster, M.; Pulverer, J.; Sahle, S.; Kuepfer, L.; Kummer, U. A comparative computational analysis of IFN-alpha pharmacokinetics and its induced cellular response in mice and humans. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Costa, B.; Pereira, M.; Silva, A.; Santos, J.; Saldanha, L.; Silva, I.; Magalhães, P.; Schmidt, S.; Vale, N. Advancing Precision Medicine: A Review of Innovative In Silico Approaches for Drug Development, Clinical Pharmacology and Personalized Healthcare. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidoost, M.; Wilson, J.L. Preclinical side effect prediction through pathway engineering of protein interaction network models. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 1180–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; Rice, C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 2011, 472, 481–485, Erratum in Nature 2015, 472, 481–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glue, P.; Fang, J.W.; Rouzier-Panis, R.; Raffanel, C.; Sabo, R.; Gupta, S.K.; Salfi, M.; Jacobs, S. Pegylated interferon-alpha2b: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and preliminary efficacy data. Hepatitis C Intervention Therapy Group. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 68, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, F.T.; Gambo, Y.Y.U.; Wongsantisuk, P.; Ahmed, I.; Tariboon, J. Mathematical modeling of the effect of early detection in breast cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1626435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, A.; Shimoda, K.; Suo, S.; Fu, R.; Kirito, K.; Wu, D.; Liao, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Su, X.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics-Pharmacodynamics and Exposure-Response of Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b in Chinese and Japanese Patients With Polycythemia Vera. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2025, 13, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pognan, F.; Beilmann, M.; Boonen, H.C.M.; Czich, A.; Dear, G.; Hewitt, P.; Mow, T.; Oinonen, T.; Roth, A.; Steger-Hartmann, T.; et al. The evolving role of investigative toxicology in the pharmaceutical industry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachhani, P.; Mascarenhas, J.; Bose, P.; Hobbs, G.; Yacoub, A.; Palmer, J.M.; Gerds, A.T.; Masarova, L.; Kuykendall, A.T.; Rampal, R.K.; et al. Interferons in the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2024, 15, 20406207241229588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudal, S.; Bissantz, C.; Caruso, A.; David-Pierson, P.; Driessen, W.; Koller, E.; Krippendorff, B.-F.; Lechmann, M.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Paehler, A.; et al. Translating pharmacology models effectively to predict therapeutic benefit. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 1604–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Yao, X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y. Interferon-α and its effects on cancer cell apoptosis (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2022, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, K.; Dai, Z. Targeting cytokine and chemokine signaling pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H. Predictive Stability Testing Utilizing Accelerated Stability Assessment Program (ASAP) Studies. In Methods for Stability Testing of Pharmaceuticals; Bajaj, S., Singh, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Asmana Ningrum, R. Human interferon alpha-2b: A therapeutic protein for cancer treatment. Scientifica 2014, 2014, 970315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Human Medicinal Products. Ficha Técnica Intron A. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/es/documents/product-information/introna-epar-product-information_es.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Milanés-Virelles, M.T.; García-García, I.; Santos-Herrera, Y.; Valdés-Quintana, M.; Valenzuela-Silva, C.M.; Jiménez-Madrigal, G.; Ramos-Gómez, T.I.; Bello-Rivero, I.; Fernández-Olivera, N.; Sánchez-de la Osa, R.B.; et al. Adjuvant interferon gamma in patients with pulmonary atypical Mycobacteriosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Ficha técnica Immukin. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/pdfs/es/ft/60113/60113_ft.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Brown, J.G. Chapter 20—Impact of Product Attributes on Preclinical Safety Evaluation. In A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Preclinical Drug Development; Faqi, A.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 479–488. [Google Scholar]

- Erhirhie, E.; Chibueze, I.; Emmanuel, I. Advances in acute toxicity testing: Strengths, weaknesses and regulatory acceptance. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2018, 11, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Ding, X. Methods of Endotoxin Detection. J. Lab. Autom. 2015, 20, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Barwal, A.; Sharma, N.; Mir, D.S.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, V. Therapeutic proteins: Developments, progress, challenges, and future perspectives. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. European Pharmacopoeia; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), HHS. International Conference on Harmonisation; guidance on Q5E Comparability of Biotechnological/Biological Products Subject to Changes in Their Manufacturing Process; availability. Notice. Fed. Regist. 2005, 70, 37861–37862. [Google Scholar]

- Colerangle, J.B. Chapter 25—Preclinical Development of Nononcogenic Drugs (Small and Large Molecules). In A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development, 2nd ed.; Faqi, A.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 659–683. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R. Preclinical Safety Evaluation of Biopharmaceuticals: A Science-Based Approach to Facilitating Clinical Trials; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, A.; Rice, T.W.; McLain, D.; Herzog, P.; Budd, G.T.; Murthy, S.; Kirby, T.J.; Bukowski, R.M. A phase I trial of intrapleural recombinant human interferon alpha (rHuIFN alpha 2b) in patients with malignant pleural effusions. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1994, 120, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Hao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Z.; Yao, L.; Wang, S.; et al. Clinical outcomes after HBsAg clearance in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with Peg-IFN α: A study with an 11- to 173-month follow-up. Virol. Sin. 2025, 40, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, K.; Bruin, G.; Escandón, E.; Funk, C.; Pereira, J.N.S.; Yang, T.-Y.; Yu, H. Characterizing the Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Therapeutic Proteins: An Industry White Paper. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, N.; Allie, S.R.; Strauss, B.E. Editorial: Interferons: Key modulators of the immune system in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1327311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, S.K.; Abdul Qadir, M.; Mahmood, N.; Ahmed, M. PEGylation of human interferon-α2b with modified amino acids increases circulation half-life and antiproliferative activity. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2023, 17, 2272365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silega Coma, L.G.; Gerónimo Pérez, H.; Brito López, D.C.; Bustamante Pérez, Y.; Delgado Martínez, I.; Bello Rivero, I.; Furrazola Gómez, G.; Cruz Gutiérrez, O.; García Illera, G.; Izquierdo López, M.; et al. Advantages of an immunomodulatory assay for the determination of the in vitro potency of human gamma interferon. Biotecnol. Apl. 2018, 35, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Finter, N.B.; Chapman, S.; Dowd, P.; Johnston, J.M.; Manna, V.; Sarantis, N.; Sheron, N.; Scott, G.; Phua, S.; Tatum, P.B. The Use of Interferon-α in Virus Infections. Drugs 1991, 42, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongji, M.; Tongyu, W.; Li, C.; Xinhe, C.; Longti, L.; Xueqin, Q.; Hai, L.; Jie, L. The Effect of Recombinant Human Interferon Alpha Nasal Drops to Prevent COVID-19 Pneumonia for Medical Staff in an Epidemic Area. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.R.; Gerriets, V. Interferon. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, C.M.; Jarvis, B. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40 kD): A review of its use in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Drugs 2001, 61, 2263–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogihara, T.; Mizoi, K.; Ishii-Watabe, A. Pharmacokinetics of Biopharmaceuticals: Their Critical Role in Molecular Design. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.-L.; Yang, Y.H. Diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: A pressing issue. World J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.H.; Schneider, W.M.; Rice, C.M. Interferons and viruses: An evolutionary arms race of molecular interactions. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Iwasaki, A. Type I and type III interferons–induction, signaling, evasion, and application to combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, A.M.B.; Piochi, L.F.; Gaspar, A.T.; Preto, A.J.; Rosário-Ferreira, N.; Moreira, I.S. Advancing Drug Safety in Drug Development: Bridging Computational Predictions for Enhanced Toxicity Prediction. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R. The Role of Structure in the Biology of Interferon Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 606489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, K.C.; Dziulko, A.; An, J.; Pekovic, F.; Cheng, A.X.; Liu, G.Y.; Lee, O.V.; Turner, D.J.; Lari, A.; Gaidt, M.M.; et al. SP140–RESIST pathway regulates interferon mRNA stability and antiviral immunity. Nature 2025, 643, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaldzhyan, A.; Zabrodskaya, Y.; Yolshin, N.; Kudling, T.; Lozhkov, A.; Plotnikova, M.; Ramsay, E.; Taraskin, A.; Nekrasov, P.; Grudinin, M.; et al. Clean and folded: Production of active, high quality recombinant human interferon-λ1. Process Biochem. 2021, 111, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, T.G.; Green, J.D. Comparative pathology of recombinant murine interferon-gamma in mice and recombinant human interferon-gamma in cynomolgus monkeys. Int. Rev. Exp. Pathol. 1993, 34 Pt B, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmadge, J.E. Synergy in the toxicity of cytokines: Preclinical studies. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1992, 14, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Luo, F.; Mei, X. Development of interferon alpha-2b microspheres with constant release. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 410, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, A.L.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Bjørn, M.E.; Eickhardt-Dalbøge, C.S.; Larsen, M.K.; Nielsen, C.H.; Thomsen, C.; Rahbek Gjerdrum, L.M.; Knudsen, T.A.; et al. Combination therapy with ruxolitinib and pegylated interferon alfa-2a in newly diagnosed patients with polycythemia vera. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 5416–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, Y.; Cen, J.; Zhu, M.; Pan, J.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D.; Chen, S. Pegylated Interferon Alpha-2b in Patients With Polycythemia Vera and Essential Thrombocythemia in the Real World. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 797825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Joshi, M.; Zhao, Z.; Mitragotri, S. PEGylated therapeutics in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 9, e10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Chu, X.; Di, L.; Gao, W.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, C.; Mao, J.; Shen, H.; Tang, H.; et al. Recent advances in the translation of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics science for drug discovery and development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2751–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.I.; Villacis-Aguirre, C.A.; Sandoval, F.S.; Martin-Solano, S.; Manrique-Suárez, V.; Rodríguez, H.; Santiago-Padilla, L.; Debut, A.; Gómez-Gaete, C.; Arias, M.T.; et al. Multilayer Nanocarrier for the Codelivery of Interferons: A Promising Strategy for Biocompatible and Long-Acting Antiviral Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, G.; Barbarash, O.; Casset-Semanaz, F.; Jaber, A.; King, J.; Metz, L.; Pardo, G.; Simsarian, J.; Sørensen, P.S.; Stubinski, B. Immunogenicity and tolerability of an investigational formulation of interferon-β1a: 24- and 48-week interim analyses of a 2-year, single-arm, historically controlled, phase IIIb study in adults with multiple sclerosis. Clin. Ther. 2007, 29, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguiga, M.B.; Bonhomme-Faivre, L.; Orbach-Arbouys, S.; Farinotti, R. Modification of the P-Glycoprotein Dependent Pharmacokinetics of Digoxin in Rats by Human Recombinant Interferon-α. Pharm. Res. 2005, 22, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.A.; Rossi, D.L.; Cardillo, T.M.; Stein, R.; Goldenberg, D.M.; Chang, C.H. Preclinical studies on targeted delivery of multiple IFNα2b to HLA-DR in diverse hematologic cancers. Blood 2011, 118, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Ma, F.; Yao, L.; Gao, H.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, L. Development and biological activity of long-acting recombinant human interferon-α2b. BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertowska, P.; Smolak, K.; Mertowski, S.; Grywalska, E. Immunomodulatory Role of Interferons in Viral and Bacterial Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Bhardwaj, S.; Sikarwar, M.; Sriwastaw, S.; Sharma, G.; Gupta, M. Nanotoxicity Unveiled: Evaluating Exposure Risks and Assessing the Impact of Nanoparticles on Human Health. J. Trace Elem. Miner. 2025, 13, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowvat, M.H.; Babaeipour, V.; Rajabi-Memari, H.; Vahidi, H.; Maghsoudi, N. Overexpression of Recombinant Human Beta Interferon (rhINF-β) in Periplasmic Space of Escherichia coli. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 13, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grabarz, F.; Lopes, A.P.Y.; Barbosa, F.F.; Barazzone, G.C.; Santos, J.C.; Botosso, V.F.; Jorge, S.A.C.; Nascimento, A.; Astray, R.M.; Gonçalves, V.M. Strategies for the Production of Soluble Interferon-Alpha Consensus and Potential Application in Arboviruses and SARS-CoV-2. Life 2021, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, A.; Purkayastha, A.; Mandal, B.; Kumar, P.; Mandal, B.; Dasu, V. A novel reverse micellar purification strategy for histidine tagged human interferon gamma (hIFN-γ) protein from Pichia pastoris. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 107, 2512–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBI. Interferon Alpha-2 Precursor [Homo Sapiens]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/NP_000596.2 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- NCBI. Interferon Gamma Precursor [Homo Sapiens]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/NP_000610.2 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Tripathi, N.K.; Shrivastava, A. Recent Developments in Bioprocessing of Recombinant Proteins: Expression Hosts and Process Development. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Corujo, A.; Uchida, Y.; Saaranen, M.J.; Ruddock, L.W. Escherichia coli Cytoplasmic Expression of Disulfide-Bonded Proteins: Side-by-Side Comparison between Two Competing Strategies. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peciak, K.; Tommasi, R.; Choi, J.W.; Brocchini, S.; Laurine, E. Expression of soluble and active interferon consensus in SUMO fusion expression system in E. coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2014, 99, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowvat, M.H.; Babaeipour, V.; Rajabi Memari, H.; Vahidi, H. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions for Recombinant Human Interferon Beta Production by Escherichia coli Using the Response Surface Methodology. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015, 8, e16236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meager, A. The Interferons: Characterization and Application; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, A.Q.; Queiroz, J.A.; Passarinha, L.A. Smoothing membrane protein structure determination by initial upstream stage improvements. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5483–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.L.; Ceccarelli, E.A. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: Advances and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, L.M.; Hernández, V.E.; Rivero, E.M.; Barba de la Rosa, A.P.; Flores, J.L.; Acevedo, L.G.; De León Rodríguez, A. Optimization of culture conditions for a synthetic gene expression in Escherichia coli using response surface methodology: The case of human interferon beta. Biomol. Engl. 2007, 24, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaeipour, V.; Shojaosadati, S.A.; Maghsoudi, N. Maximizing Production of Human Interferon-γ in HCDC of Recombinant E. coli. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. IJPR 2013, 12, 563–572. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, H.P.; Mortensen, K.K. Advanced genetic strategies for recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 115, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.; Rodriguez, I.; Baez, R.; Aldana, R. Stability of an extemporaneously prepared recombinant human interferon alfa-2b eye drop formulation. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2007, 64, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozala, A.F.; Geraldes, D.C.; Tundisi, L.L.; Feitosa, V.A.; Breyer, C.A.; Cardoso, S.L.; Mazzola, P.G.; Oliveira-Nascimento, L.; Rangel-Yagui, C.O.; Magalhães, P.O.; et al. Biopharmaceuticals from microorganisms: From production to purification. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47 (Suppl. 1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Fágáin, C.; Cummins, P.M.; O’Connor, B.F. Gel-filtration chromatography. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 681, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, F.; Gardner, Q.A.; Rashid, N.; Towers, G.J.; Akhtar, M. Preventing the N-terminal processing of human interferon α-2b and its chimeric derivatives expressed in Escherichia coli. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 76, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughran, S.T.; Bree, R.T.; Walls, D. Poly-Histidine-Tagged Protein Purification Using Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC). Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2699, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, A.A.; Veeranki, V.D.; Dsilva, S.J. Improving the production of human interferon gamma (hIFN-γ) in Pichia pastoris cell factory: An approach of cell level. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.S.; Gull, I.; Mahmood, M.S.; Iqbal, M.M.; Abbas, Z.; Tipu, I.; Ahmed, A.; Athar, M.A. High yield expression, characterization, and biological activity of IFNα2-Tα1 fusion protein. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 50, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, A.I.; Domingues, L.; Aguiar, T.Q. Tag-mediated single-step purification and immobilization of recombinant proteins toward protein-engineered advanced materials. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 36, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, B.; Gerszberg, A.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K. A Brief Reminder of Systems of Production and Chromatography-Based Recovery of Recombinant Protein Biopharmaceuticals. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 4216060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, D.; Sharma, C.; Jaglan, S.; Lichtfouse, E. Pharmaceuticals from Microbes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiäinen, T.; Peltoniemi, M.; Sarkhel, S.; Yrjönen, T.; Vuorela, H.; Urtti, A.; Juppo, A. Formulation and Stability of Cytokine Therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceaglio, N.; Gugliotta, A.; Tardivo, M.B.; Cravero, D.; Etcheverrigaray, M.; Kratje, R.; Oggero, M. Improvement of in vitro stability and pharmacokinetics of hIFN-α by fusing the carboxyl-terminal peptide of hCG β-subunit. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 221, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.R.A.; Lima, B.M.M.P.; de Moura, W.C.; Nogueira, A.C.M.D.A. Reduction of cell viability induced by IFN-alpha generates impaired data on antiviral assay using Hep-2C cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2013, 400, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Veroli, G.Y.; Fornari, C.; Goldlust, I.; Mills, G.; Koh, S.B.; Bramhall, J.L.; Richards, F.M.; Jodrell, D.I. An automated fitting procedure and software for dose-response curves with multiphasic features. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, S.; Familletti, P.C.; Pestka, S. Convenient assay for interferons. J. Virol. 1981, 37, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bis, R.L.; Stauffer, T.M.; Singh, S.M.; Lavoie, T.B.; Mallela, K.M.G. High yield soluble bacterial expression and streamlined purification of recombinant human interferon α-2a. Protein Expr. Purif. 2014, 99, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: A review. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, P.; Shen, X.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Suksamrarn, A.; Zhang, G.; Wang, F. Emodin potentiates the antiproliferative effect of interferon α/β by activation of JAK/STAT pathway signaling through inhibition of the 26S proteasome. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 4664–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.-J.; Chen, F.-Z.; Chen, H.-C.; Wan, X.-X.; Zhou, X.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, D.-Z. ISG15 inhibits cancer cell growth and promotes apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelke, G.; Jagtap, J.; Kim, D.-K.; Shah, R.; Das, G.; Shivayogi, M.; Pujari, R.; Shastry, P. TNF-α and IFN-γ Together Up-Regulates Par-4 Expression and Induce Apoptosis in Human Neuroblastomas. Biomedicines 2017, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.-Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, L. Interferon α Induces the Apoptosis of Cervical Cancer HeLa Cells by Activating both the Intrinsic Mitochondrial Pathway and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, L.; Castro-Manrreza, M.E. TNF-α and IFN-γ Participate in Improving the Immunoregulatory Capacity of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells: Importance of Cell–Cell Contact and Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, A.A.; Codner, D.; Hirasawa, K.; Komatsu, Y.; Young, M.N.; Steimle, V.; Drover, S. Activation of ERα signaling differentially modulates IFN-γ induced HLA-class II expression in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F.M.; Fellous, M. Regulation of HLA-DR gene by IFN-gamma. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control. J Immunol 1988, 140, 1660–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, N.; Sugimoto, M.; Yorozu, K.; Kurasawa, M.; Kondoh, O. Anti-VEGF antibody triggers the effect of anti-PD-L1 antibody in PD-L1(low) and immune desert-like mouse tumors. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 47, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, P.G.; Lim, S.A.; Huang, C.S.; Sharma, P.; Dagdas, Y.S.; Bulutoglu, B.; Sockolosky, J.T. Engineering interferons and interleukins for cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2022, 182, 114112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, H.; Dingfelder, F.; Condado Morales, I.; Patel, B.; Heding, K.E.; Bjelke, J.R.; Egebjerg, T.; Butté, A.; Sokolov, M.; Lorenzen, N.; et al. Design of Biopharmaceutical Formulations Accelerated by Machine Learning. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3843–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Moon, D.B.; Kim, N.Y.; Shin, Y.K. Stability and Activity of the Hyperglycosylated Human Interferon-β R27T Variant. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Khan, S.; Sun, A.; Bai, Q.; Cheng, H.; Akhtari, K. Enhancement of interferon gamma stability as an anticancer therapeutic protein against hepatocellular carcinoma upon interaction with calycosin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingman, R.; Balu-Iyer, S.V. Immunogenicity of Protein Pharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1637–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarji, B.; Abed, S.N.; Bairagi, U.; Deb, P.K.; Al-Attraqchi, O.; Choudhury, A.A.; Tekade, R.K. Chapter 18—Four Stages of Pharmaceutical Product Development: Preformulation, Prototype Development and Scale-Up, Biological Aspects, and Commercialization. In Dosage Form Design Considerations; Tekade, R.K., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 637–668. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, S.W.; Knight, R.; Royle, J.; Stephenson, L. Chapter 22—Pharmaceutical toxicology. In Principles of Translational Science in Medicine, 3rd ed.; Wehling, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Huang, Y.-F.; Liang, J.; Zhou, H. Improved up-and-down procedure for acute toxicity measurement with reliable LD50 verified by typical toxic alkaloids and modified Karber method. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (OECD Publishing). Test No. 425: Acute Oral Toxicity: Up-and-Down Procedure; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Borgert, C.J.; Fuentes, C.; Burgoon, L.D. Principles of dose-setting in toxicology studies: The importance of kinetics for ensuring human safety. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 3651–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH Expert Working Group. M3(R2) Nonclinical Safety Studies for the Conduct of Human Clinical Trials and Marketing Authorization for Pharmaceuticals. 2013. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/71542/download (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Miklosz, J.; Kalaska, B.; Zajaczkowski, S.; Pawlak, D.; Mogielnicki, A. Monitoring of Cardiorespiratory Parameters in Rats—Validation Based on Pharmacological Stimulation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K.; Ebert, O.; Suriawinata, A.; Thung, S.N.; Woo, S.L. Prophylactic alpha interferon treatment increases the therapeutic index of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus virotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in immune-competent rats. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13705–13713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, F.; Corvaro, M.; Andrus, A.; Burke, J.; Daston, G.; Delaney, B.; Domoradzki, J.; Forlini, C.; Green, M.L.; Hofmann, T.; et al. Recommendations on dose level selection for repeat dose toxicity studies. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1921–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (OECD Publishing). Test No. 407: Repeated Dose 28-day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wangikar, P.; Sandhya, M.; Choudhari, P. Exploring the Intraperitoneal Route in a New Way for Preclinical Testing. In Exploring Drug Delivery to the Peritoneum; Shegokar, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Shoyaib, A.A.; Archie, S.; Karamyan, V. Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should it Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies? Pharm. Res. 2019, 37, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USP-42-NF37; The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc.: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019.

- Food and Drug Administration. Bacterial Endotoxins/Pyrogens. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/inspection-technical-guides/bacterial-endotoxinspyrogens (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Gad, S.C.; Pham, T. Safrole. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, H.; Merika, A.; Ningrum, R.A.; Anggadiredja, K.; Retnoningrum, D.S. Evaluation of adverse effects of mutein forms of recombinant human interferon alpha-2b in female swiss webster mice. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 943687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Ma, L.L.; Jiang, J.D.; Pang, R.; Chen, Y.J.; Li, Y.H. Recombinant human interferon alpha 2b broad-spectrum anti-respiratory viruses pharmacodynamics study in vitro. Yao Xue Xue Bao Acta Pharm. Sin. 2014, 49, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, S.; Strander, H. Is interferon tissue specific?—Effect of human leukocyte and fibroblast interferons on the growth of lymphoblastoid and osteosarcoma cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 35, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.D.; Al-Humadi, N.H. Chapter 27—Preclinical Toxicology of Vaccines11Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this chapter have not been formally disseminated by the Food and Drug Administration and should not be construed to represent any Agency determination or policy. In A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development, 2nd ed.; Faqi, A.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 709–735. [Google Scholar]

- Nantachit, N.; Sunintaboon, P.; Ubol, S. Responses of primary human nasal epithelial cells to EDIII-DENV stimulation: The first step to intranasal dengue vaccination. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Dziergowska, K.; Alagawany, M.; Farag, M.R.; El-Shall, N.A.; Tuli, H.S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K. The effect of metal-containing nanoparticles on the health, performance and production of livestock animals and poultry. Vet. Q. 2022, 42, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducournau, C.; Moiré, N.; Carpentier, R.; Cantin, P.; Herkt, C.; Lantier, I.; Betbeder, D.; Dimier-Poisson, I. Effective Nanoparticle-Based Nasal Vaccine Against Latent and Congenital Toxoplasmosis in Sheep. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.P.; Moreira, J.N.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Silva, A.C. Intranasal delivery of nanostructured lipid carriers, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsions: A current overview of in vivo studies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias-Valle, L.; Finkelstein-Kulka, A.; Manji, J.; Okpaleke, C.; Al-Salihi, S.; Javer, A.R. Evaluation of sheep sinonasal endoscopic anatomy as a model for rhinologic research. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 4, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.T. Have safety and efficacy assessments of bioactives come of age? Mol. Asp. Med. 2023, 89, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Lima, B.; Videira, M.A. Toxicology and Biodistribution: The Clinical Value of Animal Biodistribution Studies. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 8, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doroud, D.; Daneshi, M.; Kazemi-Lomedash, F.; Eftekhari, Z. Comprehensive review of preclinical evaluation strategies for COVID-19 vaccine candidates: Assessing immunogenicity, toxicology, and safety profiles. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2025, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, F.P.; Gander, M.; Kuster, B.; The, M. CurveCurator: A recalibrated F-statistic to assess, classify, and explore significance of dose–response curves. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P. Chapter Eight—Structural basis of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase nucleotide addition cycle in picornaviruses. In The Enzymes; Cameron, C.E., Arnold, J.J., Kaguni, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 49, pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Interferon α-2b European Pharmacopoeia (EP) Reference Standard. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/EC/es/product/sial/i0320301 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Interferon gamma Standard. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/antibody/product/Human-IFN-gamma-Recombinant-Protein/RP-8607 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Chauhan, Y.S.; Nex, R.; Sevak, G.; Rathore, M.S. Stability Testing of Pharmaceutical Products. J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleci Çelik, F.; Karaduman, G. A multivariate interpolation approach for predicting drug LD50 value. J. Fac. Pharm. Ank. Univ. 2024, 48, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etna, M.; Giacomini, E.; Rizzo, F.; Severa, M.; Ricci, D.; Shaid, S.; Lambrigts, D.; Valentini, S.; Stampino, L.G.; Alleri, L.; et al. Optimization of the monocyte-activation-test for evaluating pyrogenicity of tick-borne encephalitis virus vaccine. ALTEX-Altern. Anim. Exp. 2020, 37, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Body Weight/Treatment | Group I Control | Group II rhIFNα-2b 10,000,000 IU/kg | Group III rhIFNα-2b 30,000,000 IU/kg | Group IV rhIFN-γ 10,000,000 IU/kg | ANOVA F (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Start/Mean ± SD | 26.8 ± 0.9 | 26.5 ± 0.8 * | 26.6 ± 1.2 * | 27.2 ± 0.7 | 0.952 (0.429) | |

| End/Mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 0.7 | 25.6 ± 0.7 * | 25.1 ± 1.2 * | 26.3 ± 1.6 | 2.526 (0.078) | |

| p (Student’s t) | Start vs. End | 0.108 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.059 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, T.I.; Villacis-Aguirre, C.A.; Lamazares, E.; Manrique-Suárez, V.; Sandoval, F.; Culqui-Tapia, C.N.; Martin-Solano, S.; Mansilla, R.; Cabezas, I.; Sánchez, O.; et al. From Genetic Engineering to Preclinical Safety: A Study on Recombinant Human Interferons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411982

Ramos TI, Villacis-Aguirre CA, Lamazares E, Manrique-Suárez V, Sandoval F, Culqui-Tapia CN, Martin-Solano S, Mansilla R, Cabezas I, Sánchez O, et al. From Genetic Engineering to Preclinical Safety: A Study on Recombinant Human Interferons. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411982

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Thelvia I., Carlos A. Villacis-Aguirre, Emilio Lamazares, Viana Manrique-Suárez, Felipe Sandoval, Cristy N. Culqui-Tapia, Sarah Martin-Solano, Rodrigo Mansilla, Ignacio Cabezas, Oliberto Sánchez, and et al. 2025. "From Genetic Engineering to Preclinical Safety: A Study on Recombinant Human Interferons" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411982

APA StyleRamos, T. I., Villacis-Aguirre, C. A., Lamazares, E., Manrique-Suárez, V., Sandoval, F., Culqui-Tapia, C. N., Martin-Solano, S., Mansilla, R., Cabezas, I., Sánchez, O., Donoso-Erch, S., Parra, N. C., Contreras, M. A., & Santiago-Vispo, N. (2025). From Genetic Engineering to Preclinical Safety: A Study on Recombinant Human Interferons. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411982