Modeling Glioblastoma with Brain Organoids: New Frontiers in Oncology and Space Research

Abstract

1. Background

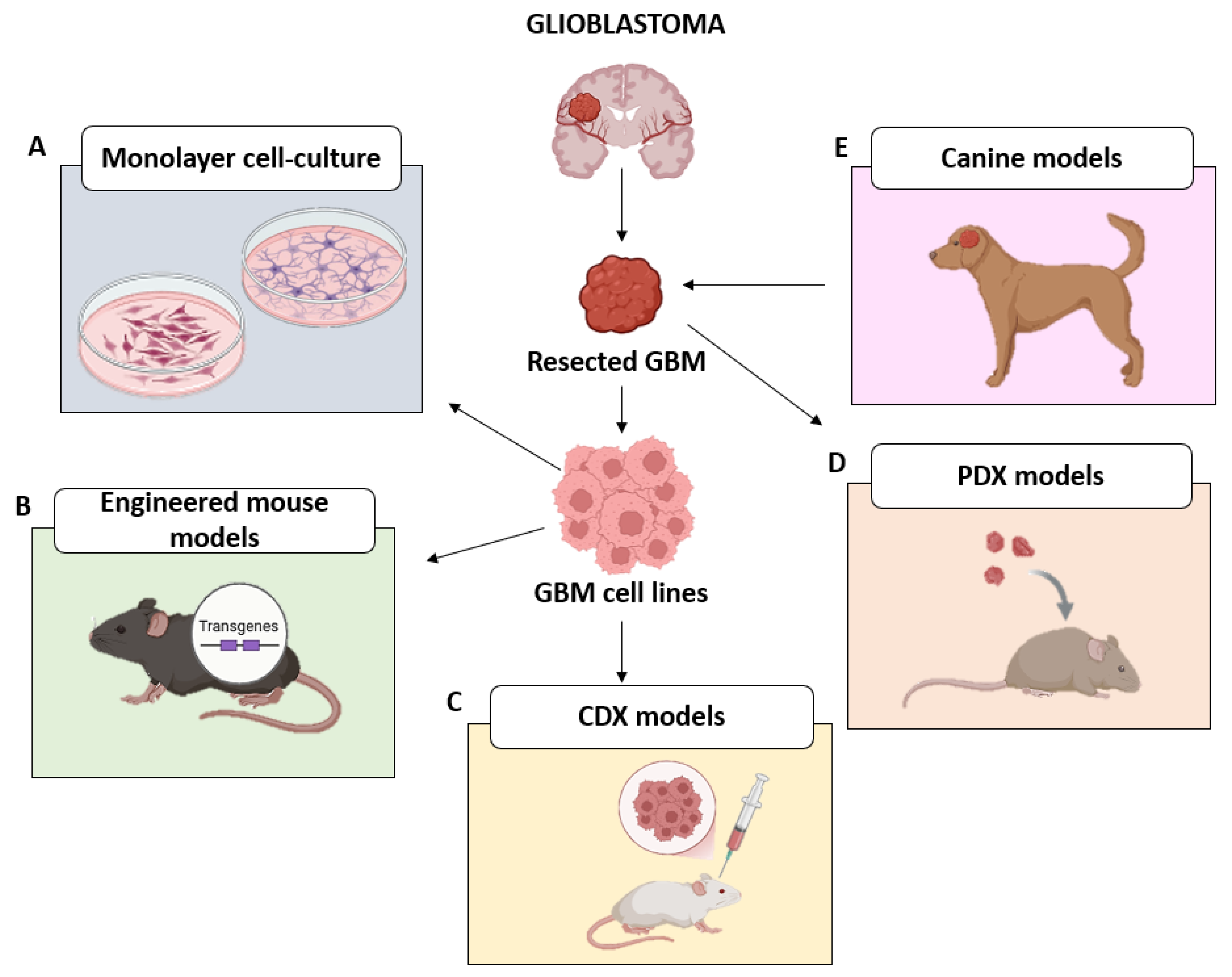

2. Conventional Approaches in GBM Research

2.1. 2D Models

2.2. In Vivo Models

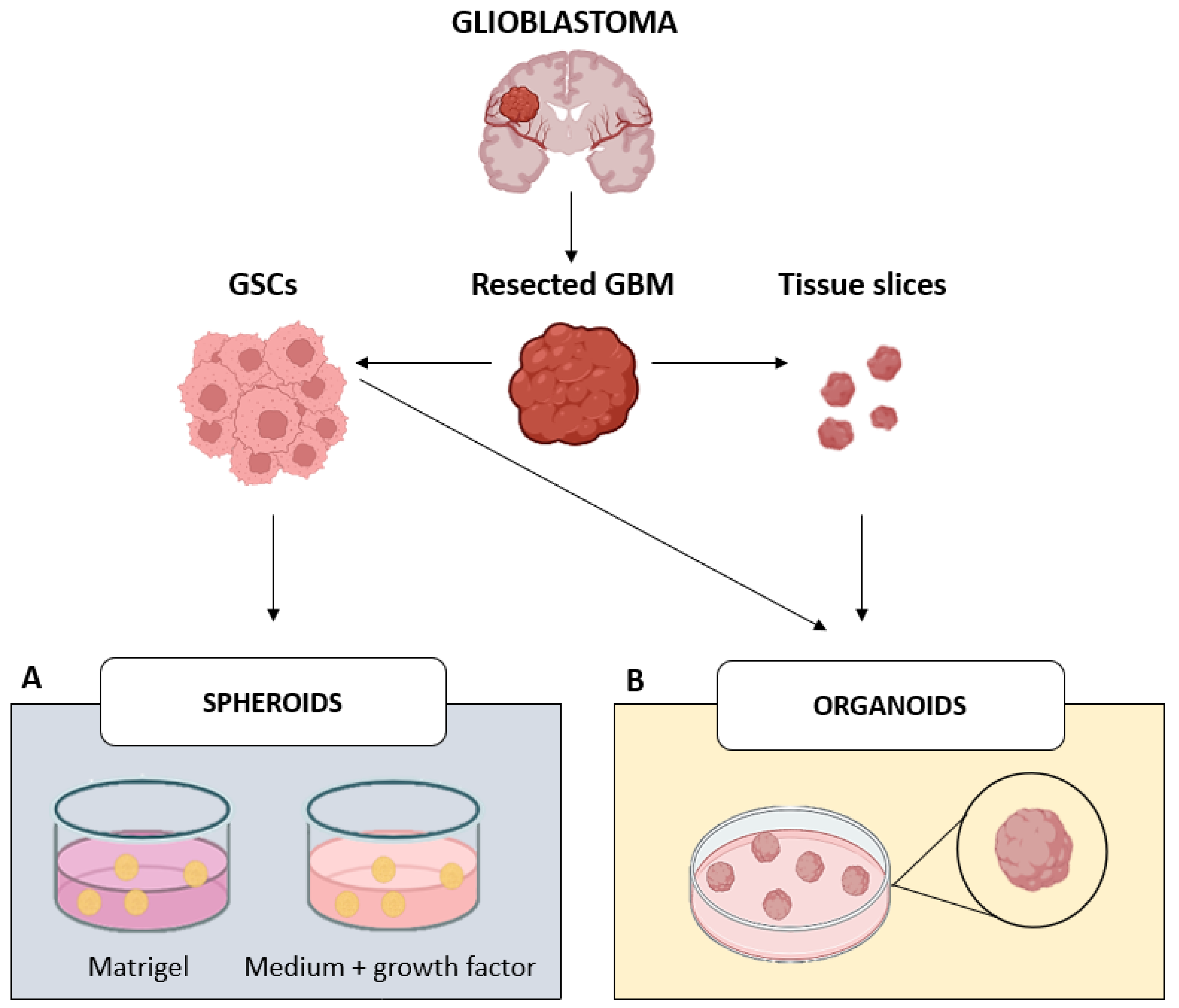

3. In Vitro 3D Models: The Bridge Between Past and Future of GBM Research

3.1. Spheroids

3.2. Organoids

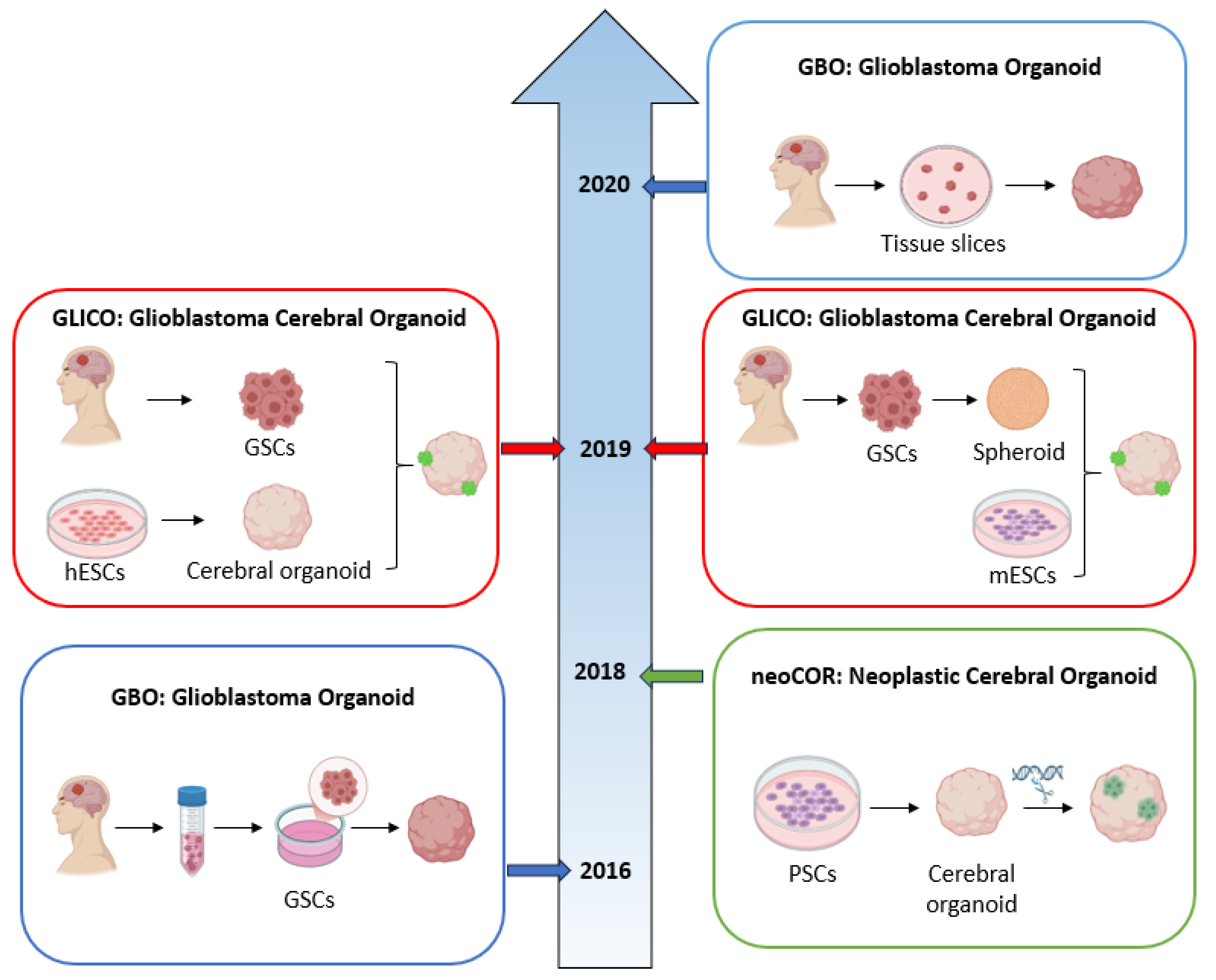

3.2.1. GBO: Glioblastoma Organoid

3.2.2. NeoCOR: Neoplastic Cerebral Organoid

3.2.3. GLICO: Glioblastoma Cerebral Organoid

4. Clinical Applications of GBM Organoids

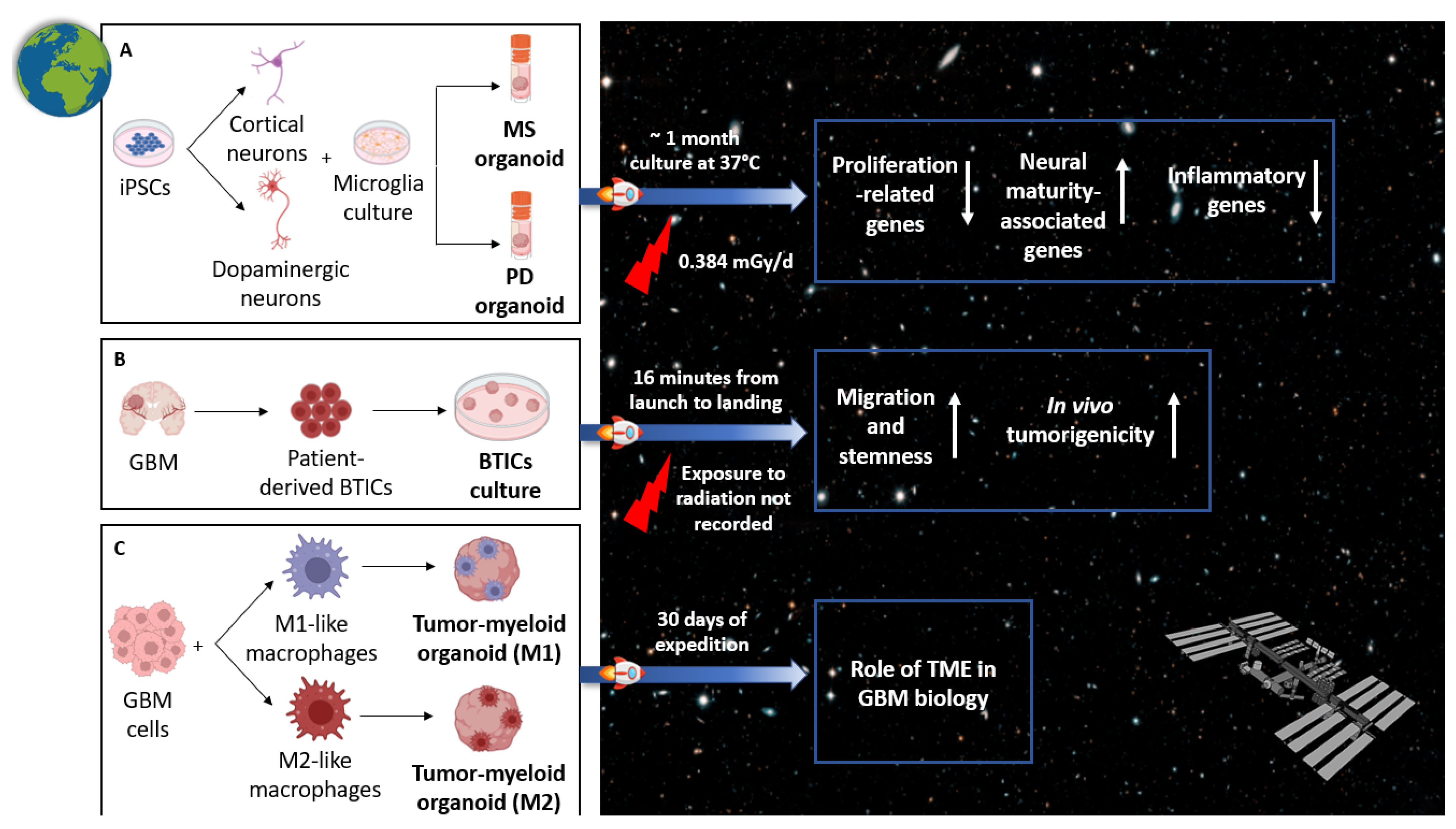

5. Modeling GBM in Space

5.1. Rationale of GBM Research in Open Space

5.2. Recent Advances in GBM Organoid Modeling in Space

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ah-Pine, F.; Khettab, M.; Bedoui, Y.; Slama, Y.; Daniel, M.; Doray, B.; Gasque, P. On the origin and development of glioblastoma: Multifaceted role of perivascular mesenchymal stromal cells. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.D.; Calado, S.M.; Matos, A.; Esteves, F.; De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Campinho, M.A.; Fernandes, M.T. Advancing Glioblastoma Research with Innovative Brain Organoid-Based Models. Cells 2025, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Price, M.; Neff, C.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2016–2020. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, iv1–iv99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Ji, Z.; Jain, V.; Smith, V.L.; Hocke, E.; Patel, A.P.; McLendon, R.E.; Ashley, D.M.; Gregory, S.G.; López, G.Y. Spatial transcriptomics reveals segregation of tumor cell states in glioblastoma and marked immunosuppression within the perinecrotic niche. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navone, S.E.; Guarnaccia, L.; Rizzaro, M.D.; Begani, L.; Barilla, E.; Alotta, G.; Garzia, E.; Caroli, M.; Ampollini, A.; Violetti, A.; et al. Role of Luteolin as Potential New Therapeutic Option for Patients with Glioblastoma through Regulation of Sphingolipid Rheostat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.; Aittaleb, M.; Tissir, F. Targeting Glioma Stem Cells: Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges. Cells 2025, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballato, M.; Germanà, E.; Ricciardi, G.; Giordano, W.G.; Tralongo, P.; Buccarelli, M.; Castellani, G.; Ricci-Vitiani, L.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Giuffrè, G.; et al. Understanding Neovascularization in Glioblastoma: Insights from the Current Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Rahman, R. Evolution of Preclinical Models for Glioblastoma Modelling and Drug Screening. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yuan, X.; Hou, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Fang, C.; Tan, Y. Development of Glioblastoma Organoids and Their Applications in Personalized Therapy. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 20, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slika, H.; Karimov, Z.; Alimonti, P.; Abou-Mrad, T.; De Fazio, E.; Alomari, S.; Tyler, B. Preclinical Models and Technologies in Glioblastoma Research: Evolution, Current State, and Future Avenues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, P.; Lightbody, J.; Sato, G.; Levine, L.; Sweet, W. Differentiated Rat Glial Cell Strain in Tissue Culture. Science 1968, 161, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigner, D.D.; Bigner, S.H.; Pontén, J.; Westermark, B.; Mahaley, M.S.; Ruoslahti, E.; Herschman, H.; Eng, L.F.; Wikstrand, C.J. Heterogeneity of Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of fifteen permanent cell lines derived from human gliomas. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1981, 40, 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccellato, C.; Rehm, M. Glioblastoma, from disease understanding towards optimal cell-based in vitro models. Cell. Oncol. 2022, 45, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumettis, D.; Kritis, A.; Foroglou, N. C6 Cell Line: The Gold Standard in Glioma Research. Hippokratia 2018, 22, 105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sibenaller, Z.A.; Etame, A.B.; Ali, M.M.; Barua, M.; Braun, T.A.; Casavant, T.L.; Ryken, T.C. Genetic Characterization of Commonly Used Glioma Cell Lines in the Rat Animal Model System. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, A.F.; Young, J.S.; Amara, D.; Berger, M.S.; Raleigh, D.R.; Aghi, M.K.; Butowski, N.A. Mouse Models of Glioblastoma for the Evaluation of Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdab100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Yang, X.J.; Wang, H.M.; Dong, X.T.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, J.M. Chemoresistance to Temozolomide in Human Glioma Cell Line U251 Is Associated with Increased Activity of O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase and Can be Overcome by Metronomic Temozolomide Regimen. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 62, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.A.; Rodgers, L.T.; Kryscio, R.J.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. Characterization and Comparison of Human Glioblastoma Models. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Oliva, R.; Domínguez-García, S.; Carrascal, L.; Abalos-Martínez, J.; Pardillo-Díaz, R.; Verástegui, C.; Castro, C.; Nunez-Abades, P.; Geribaldi-Doldán, N. Evolution of Experimental Models in the Study of Glioblastoma: Toward Finding Efficient Treatments. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 614295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyai, M.; Tomita, H.; Soeda, A.; Yano, H.; Iwama, T.; Hara, A. Current trends in mouse models of glioblastoma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 135, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.W.; Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.C.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Siu, I.M.; Gallia, G.L.; et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 2008, 321, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Roncari, L.; Shannon, P.; Wu, X.; Lau, N.; Karaskova, J.; Gutmann, D.H.; Squire, J.A.; Nagy, A.; Guha, A. Astrocyte-specific expression of activated p21-ras results in malignant astrocytoma formation in a transgenic mouse model of human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 3826–3836. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, M.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Jin, W. Organoid models of glioblastoma: Advances, applications and challenges. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 2242–2257. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, A.T.; Alférez, D.G.; Amant, F.; Annibali, D.; Arribas, J.; Biankin, A.V.; Bruna, A.; Budinská, E.; Caldas, C.; Chang, D.K.; et al. Interrogating open issues in cancer precision medicine with patient-derived xenografts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 254–268, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumchenko, E.; Paz, K.; Ciznadija, D.; Sloma, I.; Katz, A.; Vasquez-Dunddel, D.; Ben-Zvi, I.; Stebbing, J.; McGuire, W.; Harris, W.; et al. Patient-derived xenografts effectively capture responses to oncology therapy in a heterogeneous cohort of patients with solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-David, U.; Ha, G.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Greenwald, N.F.; Oh, C.; Shih, J.; McFarland, J.M.; Wong, B.; Boehm, J.S.; Beroukhim, R.; et al. Patient-derived xenografts undergo mouse-specific tumor evolution. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszthy, P.C.; Daphu, I.; Niclou, S.P.; Stieber, D.; Nigro, J.M.; Sakariassen, P.Ø.; Miletic, H.; Thorsen, F.; Bjerkvig, R. In Vivo Models of Primary Brain Tumors: Pitfalls and Perspectives. Neuro-Oncology 2012, 14, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kotliarova, S.; Kotliarov, Y.; Li, A.; Su, Q.; Donin, N.M.; Pastorino, S.; Purow, B.W.; Christopher, N.; Zhang, W.; et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshead, C.M.; van der Kooy, D. Disguising adult neural stem cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004, 14, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanai, N.; Alvarez-Buylla, A.; Berger, M.S. Neural stem cells and the origin of gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Clarke, I.D.; Terasaki, M.; Bonn, V.E.; Hawkins, C.; Squire, J.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5821–5828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paolillo, M.; Comincini, S.; Schinelli, S. In Vitro Glioblastoma Models: A Journey into the Third Dimension. Cancers 2021, 13, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Ming, G.L.; Song, H. Glioblastoma modeling with 3D organoids: Progress and challenges. Oxf. Open Neurosci. 2023, 2, kvad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, F.L.; Marqués-Torrejón, M.A.; Morrison, G.M.; Pollard, S.M. Experimental models and tools to tackle glioblastoma. Dis. Models Mech. 2019, 12, dmm040386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.; Dowbaj, A.M.; Sljukic, A.; Bratlie, K.; Lin, L.; Fong, E.L.S.; Balachander, G.M.; Chen, Z.; Soragni, A.; et al. Organoids. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauss, R.W.; Hazekamp, M.G.; Oppenhuizen, F.; van Munsteren, C.J.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; DeRuiter, M.C. Histological evaluation of decellularised porcine aortic valves: Matrix changes due to different decellularisation methods. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2005, 27, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.; Hau, A.C.; Oudin, A.; Golebiewska, A.; Niclou, S.P. Glioblastoma Organoids: Pre-Clinical Applications and Challenges in the Context of Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 604121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, C.G.; Rivera, M.; Spangler, L.C.; Wu, Q.; Mack, S.C.; Prager, B.C.; Couce, M.; McLendon, R.E.; Sloan, A.E.; Rich, J.N. A Three-Dimensional Organoid Culture System Derived from Human Glioblastomas Recapitulates the Hypoxic Gradients and Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity of Tumors Found In Vivo. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Salinas, R.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Schnoll, J.G.; Wong, S.Z.H.; Thokala, R.; Sheikh, S.; Saxena, D.; Prokop, S.; et al. A Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoid Model and Biobank Recapitulates Inter- and Intra-tumoral Heterogeneity. Cell 2020, 180, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, J.; Pao, G.M.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Verma, I.M. Glioblastoma Model Using Human Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Repic, M.; Guo, Z.; Kavirayani, A.; Burkard, T.; Bagley, J.A.; Krauditsch, C.; Knoblich, J.A. Genetically engineered cerebral organoids model brain tumor formation. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 631–639, Erratum in Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, B.; Mathew, R.K.; Polson, E.S.; Williams, J.; Wurdak, H. Spontaneous glioblastoma spheroid infiltration of early-stage cerebral organoids models brain tumor invasion. SLAS Discov. 2018, 23, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkous, A.; Balamatsias, D.; Snuderl, M.; Edwards, L.; Miyaguchi, K.; Milner, T.; Reich, B.; Cohen-Gould, L.; Storaska, A.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Modeling Patient-Derived Glioblastoma with Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3203–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybin, M.J.; Ivan, M.E.; Ayad, N.G.; Zeier, Z. Organoid Models of Glioblastoma and Their Role in Drug Discovery. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 605255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.Y.; Xing, K.; Yeo, E.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Holland, E.; Yao, L.; Qin, L.; et al. Wnt-mediated endothelial transformation into mesenchymal stem cell-like cells induces chemoresistance in glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; He, P. A reference for selecting an appropriate method for generating glioblastoma organoids from the application perspective. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaak, R.G.; Hoadley, K.A.; Purdom, E.; Wang, V.; Qi, Y.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Miller, C.R.; Ding, L.; Golub, T.; Mesirov, J.P.; et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, V.; Pospisilova, V.; Vanova, T.; Amruz Cerna, K.; Abaffy, P.; Sedmik, J.; Raska, J.; Vochyanova, S.; Matusova, Z.; Houserova, J.; et al. Glioblastoma and cerebral organoids: Development and analysis of an in vitro model for glioblastoma migration. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straehla, J.P.; Hajal, C.; Safford, H.C.; Offeddu, G.S.; Boehnke, N.; Dacoba, T.G.; Wyckoff, J.; Kamm, R.D.; Hammond, P.T. A predictive microfluidic model of human glioblastoma to assess trafficking of blood-brain barrier-penetrant nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118697119. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, D.; Fiorelli, R.; Barrientos, E.S.; Melendez, E.L.; Sanai, N.; Mehta, S.; Nikkhah, M. A three-dimensional (3D) organotypic microfluidic model for glioma stem cells—Vascular interactions. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenuwara, G.; Javed, B.; Singh, B.; Tian, F. Biosensor-Enhanced Organ-on-a-Chip Models for Investigating Glioblastoma Tumor Microenvironment Dynamics. Sensors 2024, 24, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Dai, J.; Fang, J.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Hong, Z.; Chai, Y. Construction of a novel blood brain barrier-glioma microfluidic chip model: Applications in the evaluation of permeability and anti-glioma activity of traditional Chinese medicine components. Talanta 2023, 253, 123971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Chen, M.; Lian, J.; Wang, H.; Ma, J. Glioblastoma-on-a-chip construction and therapeutic applications. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1183059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.G.; Jeong, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Moon, H.E.; Park, S.H.; Kang, K.S.; Bae, M.; Jang, J.; Youn, H.; et al. A bioprinted human-glioblastoma-on-a-chip for the identification of patient-specific responses to chemoradiotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Xie, Q.; Gimple, R.C.; Zhong, Z.; Tam, T.; Tian, J.; Kidwell, R.L.; Wu, Q.; Prager, B.C.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Three-dimensional bioprinted glioblastoma microenvironments model cellular dependencies and immune interactions. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, M.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Gamboa, C.M.; Jara, K.; Lee, H.; Sabaawy, H.E. Rapid Processing and Drug Evaluation in Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Organoid Models with 4D Bioprinted Arrays. iScience 2020, 23, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Y.T.; Chen, Y.C.; Derr, K.; Wilson, K.; Song, M.J.; Ferrer, M. A 3D Bioprinted Human Neurovascular Unit Model of Glioblastoma Tumor Growth. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2302831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, G.C.; Germani, M.M.; Caiani, E.G.; Barravecchia, I.; Passino, C.; Angeloni, D. Human Pathophysiological Adaptations to the Space Environment. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfia, G.; Navone, S.E.; Guarnaccia, L.; Campanella, R.; Locatelli, M.; Miozzo, M.; Perelli, P.; Della Morte, G.; Catamo, L.; Tondo, P.; et al. Space flight and central nervous system: Friends or enemies? Challenges and opportunities for neuroscience and neuro-oncology. J. Neurosci. Res. 2022, 100, 1649–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloulakou, S.; Poulia, K.A.; Karayiannis, D. Physiological Alterations in Relation to Space Flight: The Role of Nutrition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Liu, R.; Tian, X.; Han, Z.; Chen, J. Simulated microgravity inhibits the viability and migration of glioma via FAK/RhoA/Rock and FAK/Nek2 signaling. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Anim. 2019, 55, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.X.; Rao, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, N.D.; Si, J.W.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.C.; Wang, Z.R. Modeled microgravity suppressed invasion and migration of human glioblastoma U87 cells through downregulating store-operated calcium entry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 457, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbey, E.G.; Kim, J.; Tierney, B.T.; Park, J.; Houerbi, N.; Lucaci, A.G.; Garcia Medina, S.; Damle, N.; Najjar, D.; Grigorev, K.; et al. The Space Omics and Medical Atlas (SOMA) and international astronaut biobank. Nature 2024, 632, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, D.; Ijaz, L.; Barbar, L.; Nijsure, M.; Stein, J.; Pirjanian, N.; Kruglikov, I.; Clements, T.; Stoudemire, J.; Grisanti, P.; et al. Effects of microgravity on human iPSC-derived neural organoids on the International Space Station. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2024, 13, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A.; Suárez-Meade, P.; Brooks, M.; Bhargav, A.G.; Freeman, M.L.; Harvey, L.M.; Quinn, J.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A. Behavior of glioblastoma brain tumor stem cells following a suborbital rocket flight: Reaching the “edge” of outer space. Npj Microgravity 2023, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalad, A.; Katakowski, M.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, F.; Chopp, M. Transcription factor Sp1 induces ADAM17 and contributes to tumor cell invasiveness under hypoxia. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 28, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armento, A.; Ehlers, J.; Schötterl, S.; Naumann, U. Molecular Mechanisms of Glioma Cell Motility. In Glioblastoma; De Vleeschouwer, S., Ed.; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2017; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, B.; Khwaja, F.W.; Severson, E.A.; Matheny, S.L.; Brat, D.J.; Van Meir, E.G. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro-Oncology 2005, 7, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.H.; Tran, A.N.; Bernstock, J.D.; Etminan, T.; Jones, A.B.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Friedman, G.K.; Hjelmeland, A.B. Glioma stem cells and their roles within the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Theranostics 2021, 11, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchett, A.; Zarodniuk, M.; Lay, F.; Satpathy, I.; Zhao, W.; Torrens, K.; Marco, H.; Mendez, M.; Najera, J.; Giza, S.; et al. Abstract 5190: Leveraging the International Space Station to study glioblastoma-immune interactions in microgravity-grown organoids. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GBM Model | Features | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional models | ||||

| 2D model | Monolayer adherent cells |

|

| [9,10,19] |

| Genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) | Manipulated mouse model expressing GBM genetic alterations |

|

| [22,23,45] |

| Cell line-derived xenografts (CDX) | Established cell line implanted into mouse brain |

|

| [20] |

| Patient-derived xenografts (PDX) | Tissue fragments implanted into mouse brain |

|

| [10,19,23,45] |

| Canine model | Spontaneous canine GBM |

|

| [10] |

| Innovative 3D in vitro models | ||||

| Spheroid | Glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) cultured as neurospheres |

|

| [2,32,33] |

| GBO | Patient-derived GSCs cultured in Matrigel |

|

| [39] |

| Patient-derived tissue fragments cultured in organoid medium |

|

| [40] | |

| neoCOR | PSC-derived cerebral organoid genetically modified by CRISPR/Cas9 technology |

|

| [41,42] |

| GLICO | Human GBM spheroids co-cultured with mouse ESC GSCs co-cultured with human-ESC derived cerebral organoid |

|

| [43,44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Begani, L.; Remore, L.G.; Ragosta, S.; Rizzaro, M.D.; Guarnaccia, L.; Alotta, G.A.; Riboni, L.; Miozzo, M.R.; Barilla, E.; Gaudino, C.; et al. Modeling Glioblastoma with Brain Organoids: New Frontiers in Oncology and Space Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110664

Begani L, Remore LG, Ragosta S, Rizzaro MD, Guarnaccia L, Alotta GA, Riboni L, Miozzo MR, Barilla E, Gaudino C, et al. Modeling Glioblastoma with Brain Organoids: New Frontiers in Oncology and Space Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110664

Chicago/Turabian StyleBegani, Laura, Luigi Gianmaria Remore, Stefania Ragosta, Massimiliano Domenico Rizzaro, Laura Guarnaccia, Giovanni Andrea Alotta, Laura Riboni, Monica Rosa Miozzo, Emanuela Barilla, Chiara Gaudino, and et al. 2025. "Modeling Glioblastoma with Brain Organoids: New Frontiers in Oncology and Space Research" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110664

APA StyleBegani, L., Remore, L. G., Ragosta, S., Rizzaro, M. D., Guarnaccia, L., Alotta, G. A., Riboni, L., Miozzo, M. R., Barilla, E., Gaudino, C., Locatelli, M., Garzia, E., Marfia, G., & Navone, S. E. (2025). Modeling Glioblastoma with Brain Organoids: New Frontiers in Oncology and Space Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110664