NETosis and Neutrophil Activity Quantification in Pediatric Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Neutrophils and Tendency for NETosis in LRP Smears and in the Suspension

2.2. Optimization of Anticoagulation

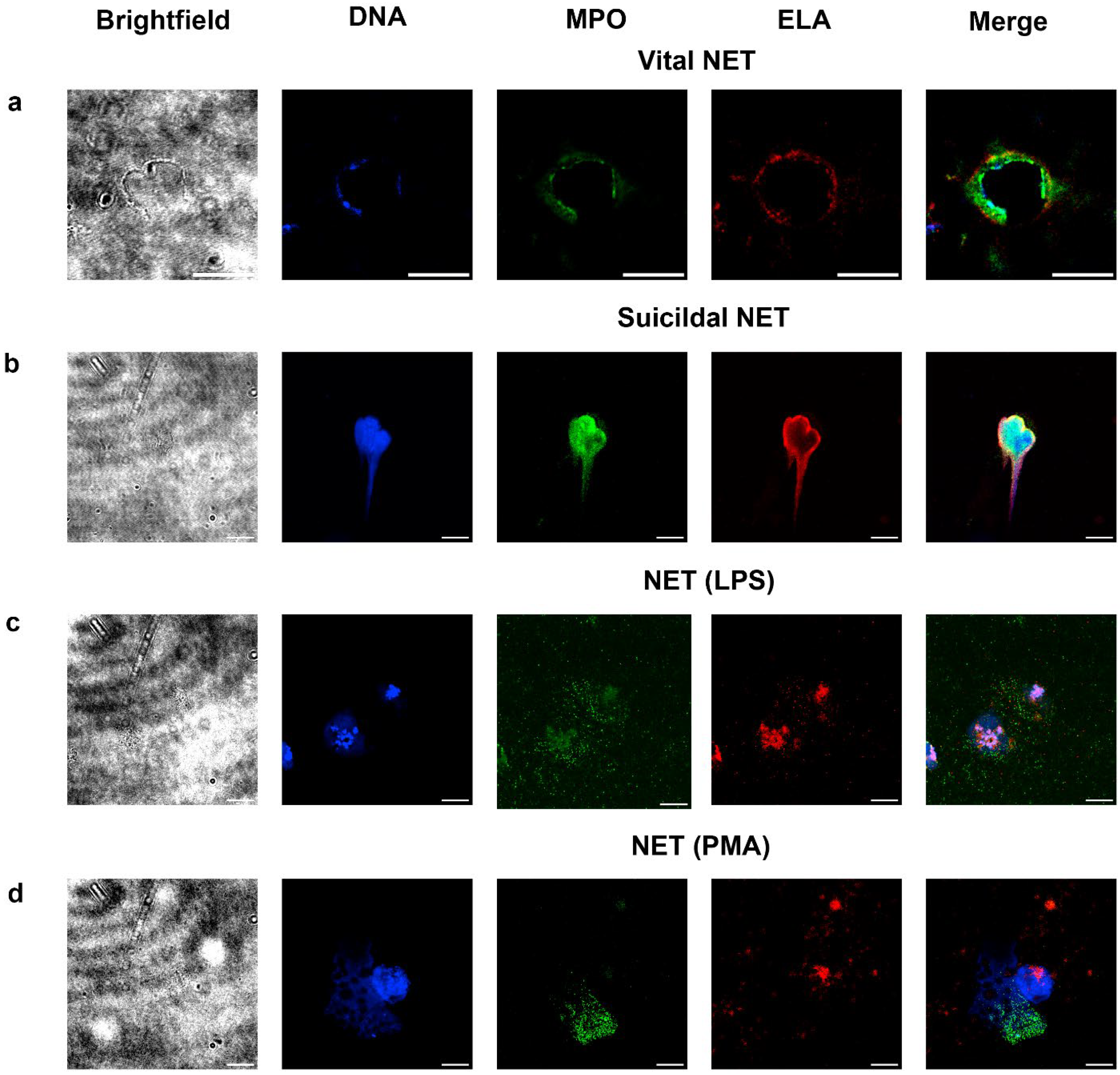

2.3. Detection of Vital and Suicidal NETosis in LRP Smears

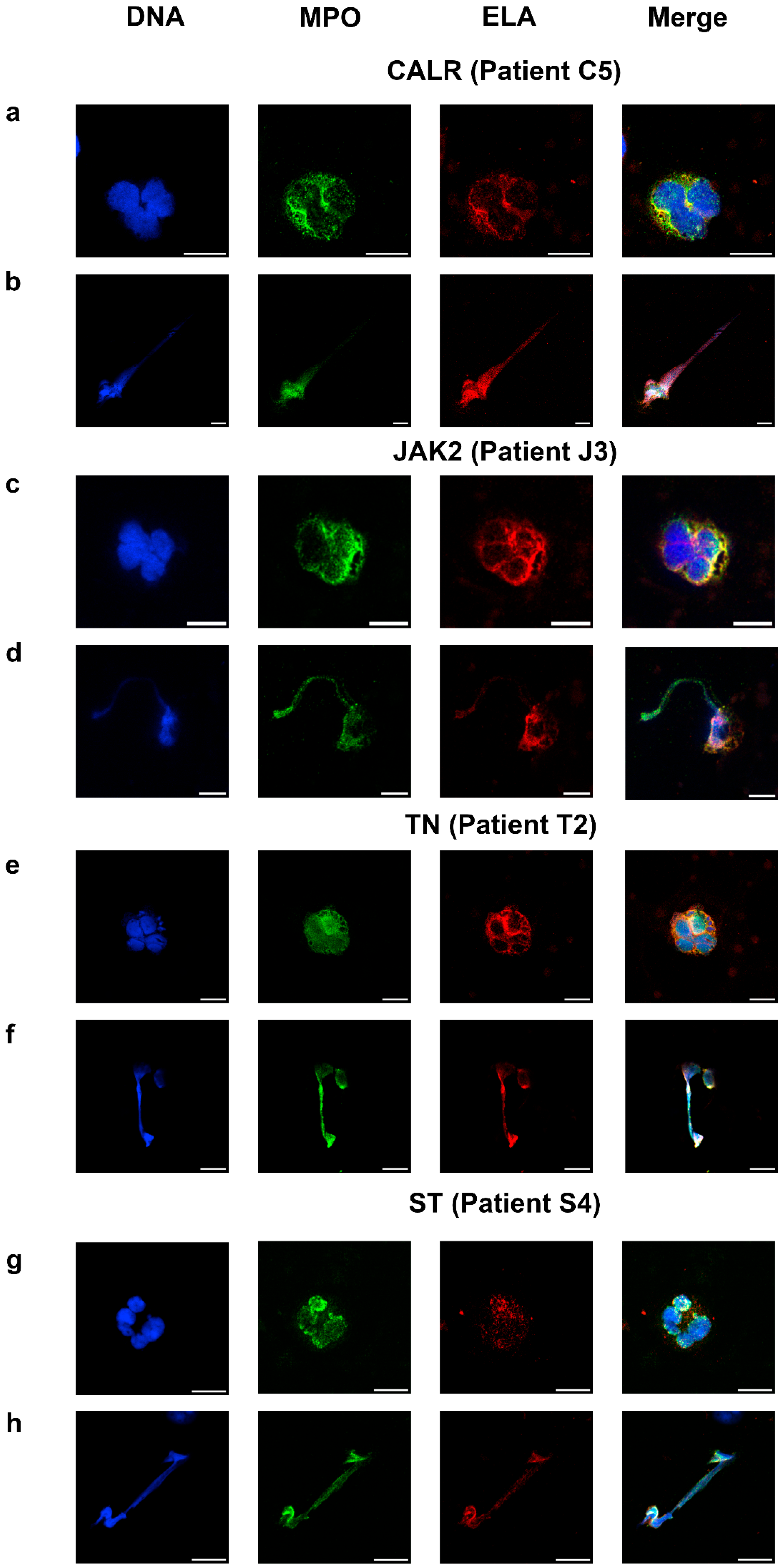

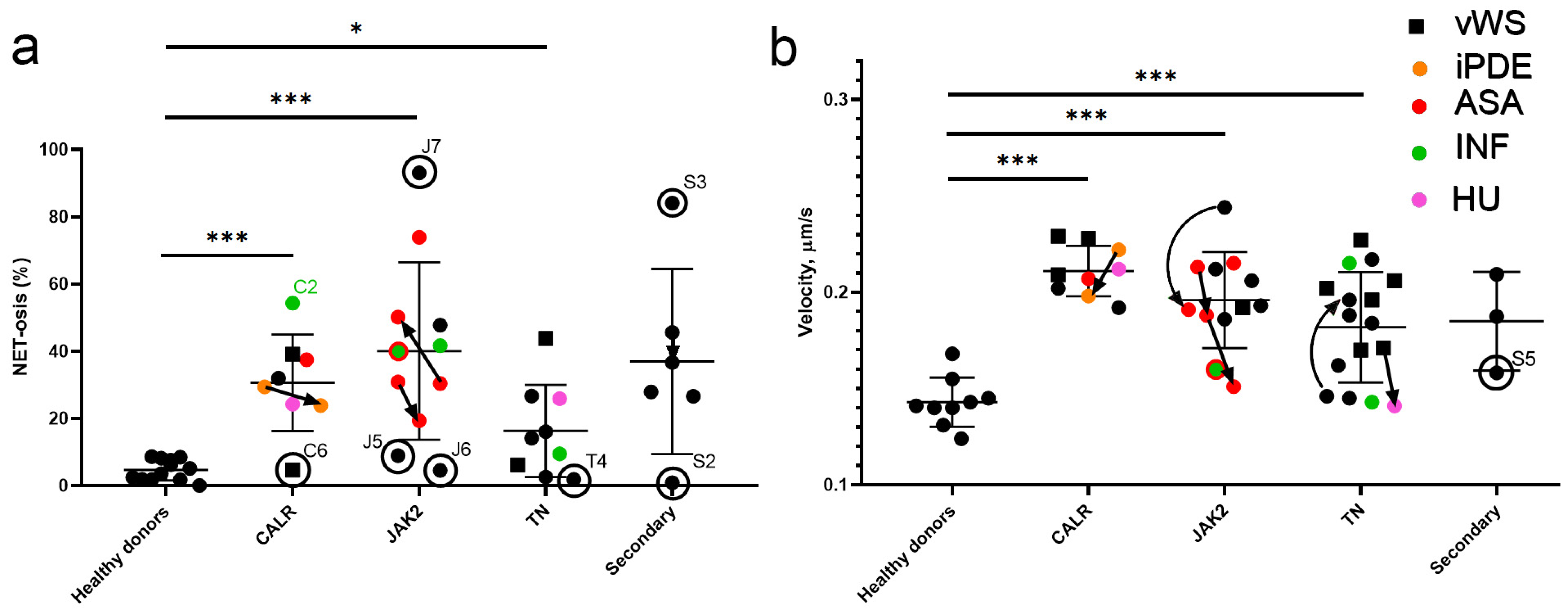

2.4. NETosis and Neutrophil Activity in Essential Thrombocythemia

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Patients and Volunteers

4.3. Immunofluorescence Microscopy of Neutrophils and NETs in LRP Smears

4.4. Immunofluorescent Microscopy of Neutrophils and NETs Produced in Suspension

4.5. Fixation and Drying of Smears

4.6. Staining of Smears

4.7. Canonical Induction of NETosis

4.8. Ex Vivo Fluorescent Microscopy

4.9. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NET | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| ET | Essential thrombocythemia |

| MPN | Myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| PV | Polycythemia vera |

| LRP | Leucocyte-rich plasma |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| PMA | Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| ELA | Neutrophil elastase |

| WN | Whole neutrophil |

| TN | Triple negative |

| ST | Secondary thrombocytosis |

| vWS | von Willebrand syndrome |

| iPDE | anagrelide |

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic acid |

| INF | Pegylated interferon alfa-2a |

| HU | Hydroxyurea |

References

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; Centre International de Recherche sur le Cancer (Eds.) WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, B.N.; Beckman, J.D. Novel Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Thrombosis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2021, 16, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.J. Myeloproliferative and thrombotic burden and treatment outcome of thrombocythemia and polycythemia patients. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 4, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.L.; Wadleigh, M.; Cools, J.; Ebert, B.L.; Wernig, G.; Huntly, B.J.P.; Boggon, T.J.; Wlodarska, I.; Clark, J.J.; Moore, S.; et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolles, B.; Mullally, A. Molecular Pathogenesis of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2022, 17, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Carobbio, A.; Cervantes, F.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Guglielmelli, P.; Antonioli, E.; Alvarez-Larrán, A.; Rambaldi, A.; Finazzi, G.; Barosi, G. Thrombosis in primary myelofibrosis: Incidence and risk factors. Blood 2010, 115, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Stefano, V.; Za, T.; Rossi, E.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Ruggeri, M.; Elli, E.; Micò, C.; Tieghi, A.; Cacciola, R.R.; Santoro, C.; et al. Recurrent thrombosis in patients with polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: Incidence, risk factors, and effect of treatments. Haematologica 2008, 93, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinod, K.; Wagner, D.D. Thrombosis: Tangled up in NETs. Blood 2014, 123, 2768–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, S.; Nakazawa, D.; Shida, H.; Miyoshi, A.; Kusunoki, Y.; Tomaru, U.; Ishizu, A. NETosis markers: Quest for specific, objective, and quantitative markers. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 459, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.K.; Arthur, J.F.; Gardiner, E.E. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and the role of platelets in infection. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 112, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Hurwitz, R.; Schulze, I.; Wahn, V.; Weinrauch, Y.; Brinkmann, V.; Zychlinsky, A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, A.; Mall, M.A. Mucus obstruction and inflammation in early cystic fibrosis lung disease: Emerging role of the IL-1 signaling pathway. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, O. The role of platelets in sepsis. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolach, O.; Sellar, R.S.; Martinod, K.; Cherpokova, D.; McConkey, M.; Chappell, R.J.; Silver, A.J.; Adams, D.; Castellano, C.A.; Schneider, R.K.; et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation promotes thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaan8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Daniliants, D.; Hiller, E.; Gunsilius, E.; Wolf, D.; Feistritzer, C. Increased levels of NETosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms are not linked to thrombotic events. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 3515–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yipp, B.G.; Petri, B.; Salina, D.; Jenne, C.N.; Scott, B.N.V.; Zbytnuik, L.D.; Pittman, K.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Wu, K.; Meijndert, H.C.; et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveshnikova, A.N.; Adamanskaya, E.A.; Panteleev, M.A. Conditions for the implementation of the phenomenon of programmed death of neutrophils with the appearance of DNA extracellular traps during thrombus formation. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. Immunopathol. 2024, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzi, R.; Pacini, S.; Testi, R.; Azzarà, A.; Galimberti, S.; Testi, C.; Trombi, L.; Metelli, M.R.; Petrini, M. Carboxy-terminal fragment of osteogenic growth peptide in vitro increases bone marrow cell density in idiopathic myelofibrosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 121, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmieder, S.; Chatain, N. Role of inflammation in the biology of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Rev. 2020, 42, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocchia, M.; Galimberti, S.; Aprile, L.; Sicuranza, A.; Gozzini, A.; Santilli, F.; Abruzzese, E.; Baratè, C.; Scappini, B.; Fontanelli, G.; et al. Genetic predisposition and induced pro-inflammatory/pro-oxidative status may play a role in increased atherothrombotic events in nilotinib treated chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 72311–72321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polokhov, D.M.; Ershov, N.M.; Ignatova, A.A.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; Gaskova, M.V.; Zharkov, P.A.; Fedorova, D.V.; Poletaev, A.V.; Seregina, E.A.; Novichkova, G.A.; et al. Platelet function and blood coagulation system status in childhood essential thrombocythemia. Platelets 2020, 31, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dömer, D.; Walther, T.; Möller, S.; Behnen, M.; Laskay, T. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Activate Proinflammatory Functions of Human Neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 636954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavillet, M.; Martinod, K.; Renella, R.; Harris, C.; Shapiro, N.I.; Wagner, D.D.; Williams, D.A. Flow cytometric assay for direct quantification of neutrophil extracellular traps in blood samples. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Yadav, S.; Chandra, T.; Mulay, S.R.; Gaikwad, A.N.; Kumar, S. An Imaging and Computational Algorithm for Efficient Identification and Quantification of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Cells 2022, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorov, K.; Barouqa, M.; Yin, D.; Kushnir, M.; Billett, H.H.; Reyes Gil, M. Identifying Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Blood Samples Using Peripheral Smear Autoanalyzers. Life 2023, 13, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, O.R.; Mora, N.; Cortes-Vieyra, R.; Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Differential Use of Human Neutrophil Fc γ Receptors for Inducing Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 2908034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S.; Ravi, J.; Rauova, L.; Johnson, A.; Lee, G.M.; Gilner, J.B.; Gunti, S.; Notkins, A.L.; Kuchibhatla, M.; Frank, M.; et al. Polyreactive IgM initiates complement activation by PF4/heparin complexes through the classical pathway. Blood 2018, 132, 2431–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorieva, D.V.; Gorudko, I.V.; Kostevich, V.A.; Vasilyev, V.B.; Cherenkevich, S.N.; Panasenko, O.M.; Sokolov, A. Exocytosis of myeloperoxidase from activated neutrophils in the presence of heparin. Biomeditsinskaya Khimiya 2018, 64, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Zlatar, L.; Muñoz-Becerra, M.; Lochnit, G.; Herrmann, I.; Pfister, F.; Janko, C.; Knopf, J.; Leppkes, M.; Schoen, J.; et al. Calpain-1 weakens the nuclear envelope and promotes the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaninetti, C.; Vater, L.; Kaderali, L.; Crodel, C.C.; Schnöder, T.M.; Fuhrmann, J.; Swensson, L.; Wesche, J.; Freyer, C.; Greinacher, A.; et al. Immunofluorescence microscopy on the blood smear identifies patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia 2024, 38, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Buhr, N.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M. How Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Become Visible. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, e4604713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilsczek, F.H.; Salina, D.; Poon, K.K.H.; Fahey, C.; Yipp, B.G.; Sibley, C.D.; Robbins, S.M.; Green, F.H.Y.; Surette, M.G.; Sugai, M.; et al. A Novel Mechanism of Rapid Nuclear Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation in Response to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyanov, A.A.; Boldova, A.E.; Stepanyan, M.G.; An, O.I.; Gur’ev, A.S.; Kassina, D.V.; Volkov, A.Y.; Balatskiy, A.V.; Butylin, A.A.; Karamzin, S.S.; et al. Longitudinal multiparametric characterization of platelet dysfunction in COVID-19, Effects of disease severity, anticoagulation therapy and inflammatory status. Thromb. Res. 2022, 211, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, D.; Kurz, T.; Motamedi, A.; Hellmark, T.; Eriksson, P.; Segelmark, M. Increased levels of neutrophil extracellular trap remnants in the circulation of patients with small vessel vasculitis, but an inverse correlation to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies during remission. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Goosmann, C.; Kühn, L.I.; Zychlinsky, A. Automatic quantification of in vitro NET formation. Front. Immunol. 2013, 3, 41017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorov, A.S.; Shepelyuk, T.O.; Balabin, F.A.; Martyanov, A.A.; Nechipurenko, D.Y.; Sveshnikova, A.N. Modeling of Granule Secretion upon Platelet Activation through the TLR4-Receptor. Biophysics 2018, 63, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Silva, L.M.R.; Conejeros, I.; Velásquez, Z.D.; Hirz, M.; Gärtner, U.; Jacquiet, P.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C. Besnoitia besnoiti bradyzoite stages induce suicidal- and rapid vital-NETosis. Parasitology 2020, 147, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Fogg, D.K.; Kaplan, M.J. A novel image-based quantitative method for the characterization of NETosis. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 423, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chi, D.; Ju, S.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Mang, G.; et al. Platelet factor 4 promotes deep venous thrombosis by regulating the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Thromb. Res. 2024, 237, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Moriconi, F.R.; Galimberti, S.; Libby, P.; De Caterina, R. The JAK–STAT pathway: An emerging target for cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4389–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, T.P.; Xue, C.; Yalcinkaya, M.; Hardaway, B.; Abramowicz, S.; Xiao, T.; Liu, W.; Thomas, D.G.; Hajebrahimi, M.A.; Pircher, J.; et al. The AIM2 inflammasome exacerbates atherosclerosis in clonal haematopoiesis. Nature 2021, 592, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freysd’ottir, J. Production of Monoclonal Antibodies. In Diagnostic and Therapeutic Antibodies [Internet]; George, A.J.T., Urch, C.E., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Thiele, J.; Gisslinger, H.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Guglielmelli, P.; Orazi, A.; Tefferi, A. The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: Document summary and in-depth discussion. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Pecci, A.; Kunishima, S.; Althaus, K.; Nurden, P.; Balduini, C.L.; Bakchoul, T. Diagnosis of inherited platelet disorders on a blood smear: A tool to facilitate worldwide diagnosis of platelet disorders. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkin, J.-J.D.; Deordieva, E.A.; Tesakov, I.P.; Adamanskaya, E.-I.A.; Boldova, A.E.; Boldyreva, A.A.; Galkina, S.V.; Lazutova, D.P.; Martyanov, A.A.; Pustovalov, V.A.; et al. Dissecting thrombus-directed chemotaxis and random movement in neutrophil near-thrombus motion in flow chambers. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, D.S.; Martyanov, A.A.; Obydennyi, S.I.; Korobkin, J.-J.D.; Sokolov, A.V.; Shamova, E.V.; Gorudko, I.V.; Khoreva, A.L.; Shcherbina, A.; Panteleev, M.A.; et al. Ex vivo observation of granulocyte activity during thrombus formation. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechipurenko, D.Y.; Receveur, N.; Yakimenko, A.O.; Shepelyuk, T.O.; Yakusheva, A.A.; Kerimov, R.R.; Obydennyy, S.I.; Eckly, A.; Leon, C.; Gachet, C.; et al. Clot Contraction Drives the Translocation of Procoagulant Platelets to Thrombus Surface. Arter. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kruchten, R.; Cosemans, J.M.E.M.; Heemskerk, J.W.M. Measurement of whole blood thrombus formation using parallel-plate flow chambers—A practical guide. Platelets 2012, 23, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, J.C.; Hoffman, B.D. Multiple-particle tracking and two-point microrheology in cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2007, 83, 141–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Patient | Genetics | Point | Age, y | PLT ## 204–356 109/L | NEUT ## 1.5–8.5 109/L | Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome | Treatment * | NET/PMNs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALR | C1 | CALR (exon 9) 42.8% $ | 1 | 12 | 617 | 5.44 | iPDE | 63/214 | |

| 2 | 12 | 230 | 1.67 | iPDE | 11/46 | ||||

| C2 | CALR (exon 9) | 1 | 13 | 393 | 2.7 | INF | 89/164 | ||

| C3 | CALR (exon 9) 37% $ | 1 | 15 | 894 | 6.19 | - | 8/25 | ||

| C4 | CALR (exon 9) | 1 | 17 | 1695 | 5.03 | ASA | 54/144 | ||

| C5 | CALR (exon 9) 11% $# | 1 | 15 | 167 | 1.92 | HU | 19/78 | ||

| C6 | CALR (exon 9) 31% $ | 1 | 9 | 1868 | 7.09 | + | - | 10/213 | |

| C7 | CALR (exon 9) 39.5% $ | 1 | 7 | 1832 | 5.48 | + | - | 9/23 | |

| C8 | CALR (exon 9) 59% $ | 1 | 6 | 865 | 3.07 | - | - | ||

| C9 | CALR (exon 9) | 1 | 8 | 2406 | 7.94 | + | - | - | |

| JAK2 | J1 | JAK2 (V617F) | 1 | 17 | 310 | 1.88 | INF | 10/24 | |

| J2 | JAK2 (V617F) 26% $ | 1 | 13 | 404 | 1.46 | ASA, INF | 10/25 | ||

| J3 | JAK2 (V617F) | 1 | 10 | 1651 | 5.34 | ASA | 24/79 | ||

| 2 | 10 | 1351 | 6.83 | ASA | - | ||||

| 3 | 11 | 678 | 4.75 | ASA | 100/199 | ||||

| J4 | JAK2 (V617F) 6% $ | 1 | 10 | 1199 | 4.61 | ASA | 52/168 | ||

| 2 | 11 | 1337 | 5.13 | ASA | 74/381 | ||||

| J5 | JAK2 (V617F) 11% $# | 1 | 16 | 589 | 3.96 | - | 30/332 | ||

| J6 | JAK2 (V617F) 5.5% $ | 1 | 16 | 830 | 7.54 | - | 4/87 | ||

| J7 | JAK2 (V617F) | 1 | 4 | 1280 | 7.7 | - | 3/44 & | ||

| J8 | JAK2 (V617F) 15% $# | 1 | 17 | 1156 | 7.71 | - | 44/92 | ||

| J9 | JAK2 (V617F) 14% $ | 1 | 16 | 1151 | 10.06 | - | - | ||

| 2 | 17 | 1196 | 10.3 | ASA | 99/134 | ||||

| J10 | JAK2 (V617F) 39% $ | 1 | 5 | 1172 | 8.34 | - | - | ||

| J11 | JAK2 (V617F) 32% $# | 1 | 16 | 1724 | 7.61 | + | - | - | |

| TN | T1 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 11 | 943 | 4.42 | - | 44/165 | |

| T2 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 17 | 495 | 1.52 | INF | 15/157 | ||

| T3 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) # | 1 | 13 | 1701 | 6.32 | + | - | 32/73 | |

| T4 | Negative: MPL, JAK2 | 1 | 9 | 811 | 4.13 | - | 7/366 | ||

| T5 | Negative: CALR, MPL, JAK2(12,14), BCR\ABL1 | 1 | 11 | 1840 | 9.63 | + | - | 12/192 | |

| 2 | 12 | 439 | 1.89 | HU | 7/27 | ||||

| T6 | Negative: CALR, MPL, JAK2(12) | 1 | 14 | 1072 | 3.94 | - | 27/168 | ||

| T7 | Negative: CALR, MPL, JAK2(12) | 1 | 14 | 657 | 2.15 | - | - | ||

| 2 | 15 | 848 | 3.4 | - | 4/152 | ||||

| T8 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14), 515L | 1 | 4 | 810 | 4.41 | - | 3/21 | ||

| T9 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 10 | 918 | 4.63 | INF | - | ||

| T10 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 3 | 2600 | 4.68 | + | - | - | |

| T11 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 13 | 1323 | 4.5 | - | - | ||

| T12 | Negative: CALR, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 7 | 1903 | 4.31 | + | - | - | |

| T13 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 6 | 1964 | 4.22 | + | - | - | |

| T14 | Negative: CALR, CALR-indel, MPL, JAK2(12,14) | 1 | 16 | 1824 | 6.85 | + | ASA | - | |

| Secondary | S1 | Hereditary spherocytosis after splenectomy | 1 | 6 | 762 | 3.94 | - | 36/79 | |

| 2 | 7 | 976 | 2.43 | - | 18/49 | ||||

| S2 | IDA | 1 | 6 | 602 | 3.17 | - | 2/214 | ||

| S3 | IDA | 1 | 11 | 460 | 1.44 | - | 37/44 | ||

| S4 | Asplenia | 1 | 7 | 827 | 6 | - | 131/469 | ||

| S5 | Congenital sideroblastic anemia (ABCB7 c.383A>T hetero) | 1 | 14 | 535 | 3.55 | - | 73/274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamanskaya, E.-I.A.; Korobkin, J.-J.D.; Pshonkin, A.V.; Bogdanov, A.V.; Galkina, S.V.; Podoplelova, N.A.; Yushkova, E.V.; Panteleev, M.A.; Novichkova, G.A.; Smetanina, N.S.; et al. NETosis and Neutrophil Activity Quantification in Pediatric Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411958

Adamanskaya E-IA, Korobkin J-JD, Pshonkin AV, Bogdanov AV, Galkina SV, Podoplelova NA, Yushkova EV, Panteleev MA, Novichkova GA, Smetanina NS, et al. NETosis and Neutrophil Activity Quantification in Pediatric Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411958

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamanskaya, Ekaterina-Iva A., Julia-Jessica D. Korobkin, Alexey V. Pshonkin, Alexey V. Bogdanov, Sofia V. Galkina, Nadezhda A. Podoplelova, Eugenia V. Yushkova, Mikhail A. Panteleev, Galina A. Novichkova, Nataliya S. Smetanina, and et al. 2025. "NETosis and Neutrophil Activity Quantification in Pediatric Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411958

APA StyleAdamanskaya, E.-I. A., Korobkin, J.-J. D., Pshonkin, A. V., Bogdanov, A. V., Galkina, S. V., Podoplelova, N. A., Yushkova, E. V., Panteleev, M. A., Novichkova, G. A., Smetanina, N. S., & Sveshnikova, A. N. (2025). NETosis and Neutrophil Activity Quantification in Pediatric Patients with Essential Thrombocythemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411958