Regulation of Tissue Regeneration by Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

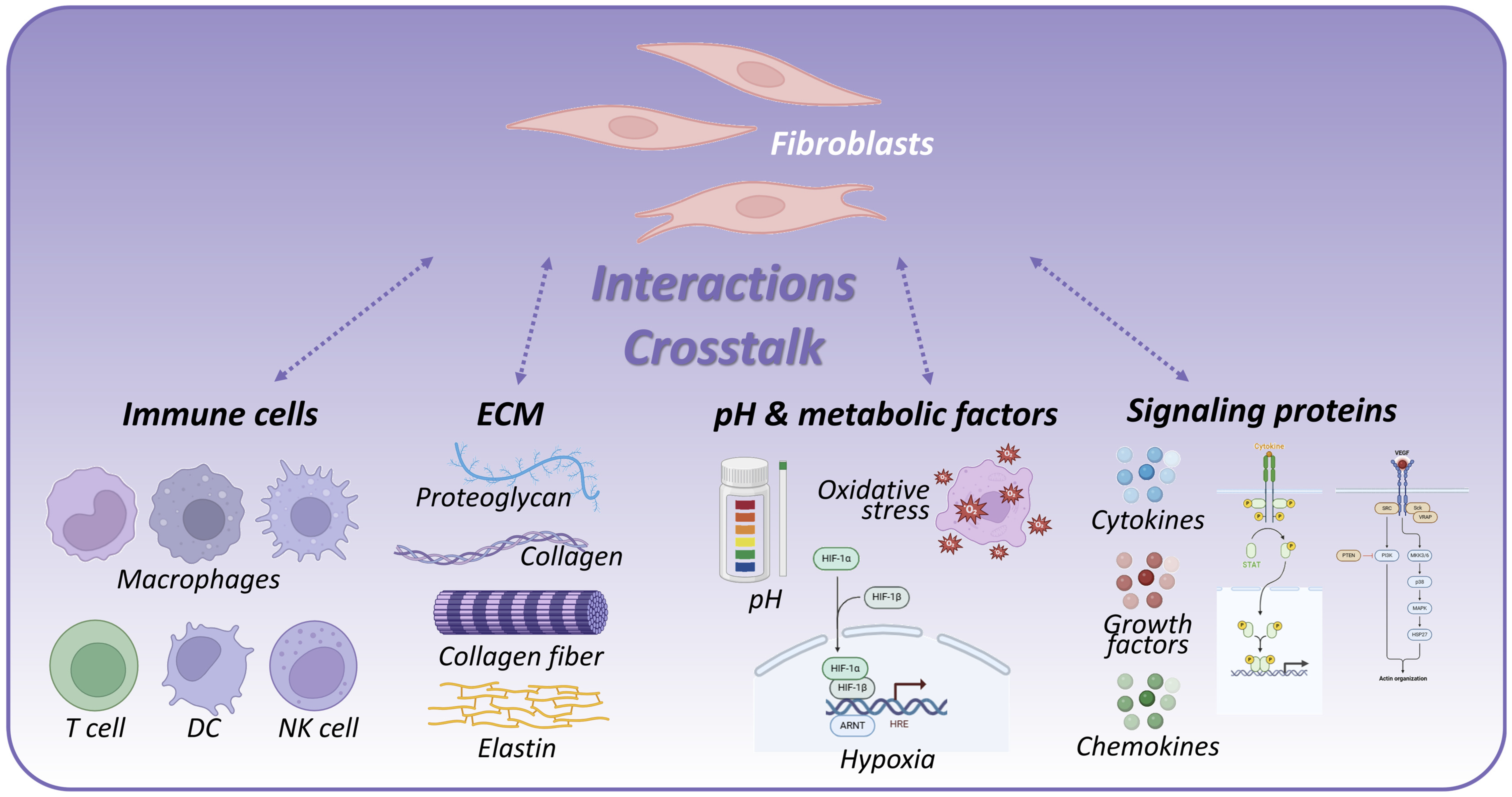

2. Components and Features of the Immune Microenvironment

2.1. Immune Cells

2.2. ECM

2.3. pH and Metabolic Environment

2.4. Proteins and Signaling Molecules

| Role and Function | Features and Impact | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Cells | |||

| Macrophages | Exhibit plasticity polarized into pro-inflammatory M1 (debris clearance) and anti-inflammatory M2 (fibroblast activation, ECM synthesis) phenotypes | M1 promotes inflammation and pathogen clearance; M2 supports tissue repair and fibrosis resolution; balance determines regenerative or fibrotic outcomes | [24,25,26] |

| T Cells | Modulate regenerative and immunologic balance via interaction with stem cells and fibroblasts | Th1 cells promote inflammation; Th2 cells promote anti-inflammatory responses and fibrosis; regulating immune balance during repair | [27] |

| DCs | Antigen presentation and immune response modulation | Influence initiation and resolution of inflammation; key to immune system education | [28] |

| NK Cells | Cytotoxic activity and immune regulation | Play roles in eliminating infected or damaged cells; contribute to inflammation resolution | |

| ECM | |||

| Collagen | Provides structural support and tissue strength | Major ECM component; influences cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation; altered composition affects healing and fibrosis | [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

| Fibronectin | Facilitates cell adhesion and migration | Acts as growth factor reservoir; mediates signal transduction pathways | |

| Elastin | Maintains tissue elasticity | Important for tissue resilience and function | |

| Proteoglycans | Modulate extracellular space, growth factor concentrations | Regulate water retention and bioavailability of signaling molecules | |

| MMPs | Mediate ECM degradation and remodeling | Critical for dynamic ECM turnover; regulate tissue repair vs. fibrosis depending on activity | [35] |

| pH and Metabolic Environment | |||

| Local pH | Regulates receptor binding, enzyme activities, signal transduction | Acidic microenvironment alters cytokine signaling, immune cell polarization, and fibroblast functions | [22,38,39,40] |

| Oxygen Levels | Influences cellular metabolism and survival | Hypoxia triggers inflammatory and fibrotic pathways; affects angiogenesis | |

| Proteins and Signaling Molecules | |||

| Cytokines | |||

| TNF-α | Promotes inflammatory responses, activates immune cells, induces clearance of cellular debris at injury sites | Enhances NF-κB activity causing feedback loop formation, amplifies and sustains inflammation, high levels can cause tissue damage and toxicity | [41,42,43] |

| IL-6 | Regulates diverse cell activation and differentiation, modulates acute inflammatory responses, involved in regeneration and fibrosis | Increases during infection and tissue damage, key to immune response regulation, chronic elevation promotes tissue damage | |

| IL-10 | Anti-inflammatory cytokine, suppresses inflammation, maintains immune balance and protects tissues | Inhibits Th1 cytokines, promotes anti-inflammatory responses, reduces excessive inflammation and tissue damage | |

| Growth Factors | |||

| FGF | Promotes cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and angiogenesis | Central role in regeneration and wound healing, important for cell regeneration and ECM remodeling | [41,42,43] |

| VEGF | Stimulates angiogenesis, enhances oxygen and nutrient supply to damaged tissues | Essential for vascular regeneration and function recovery, improves oxygen and metabolic environment | |

| EGF | Stimulates epidermal cell proliferation and differentiation, supports wound healing and tissue regeneration | Directly contributes to cell proliferation and regeneration at wound sites | |

| Chemokines | |||

| CCL2 | Recruits monocytes and macrophages, promotes immune cell recruitment to inflammation sites | Essential for immune cell mobilization and activation in inflammatory and regenerative areas | [41,42,43] |

| CXCL12 | Attracts stem cells and immune cells, promotes tissue regeneration and vascular remodeling | Key for creating regenerative environment, crucial for stem cell recruitment and function maintenance | |

3. Biological Characteristics and Functions of Fibroblasts

3.1. Migration and Proliferation

3.2. Differentiation and Mechanotransduction

3.3. ECM Synthesis and Remodeling Regulation

3.4. Immunomodulation and Regenerative Signaling

4. Fibroblast Immune Regulation: Subsets, Organ Specificity, and Signaling

4.1. Immune-Regulatory Fibroblast Subsets in Single-Cell and Spatial Omics

4.2. Tissue-Specific Fibroblast Subsets and Immune Signaling Pathways

5. The Role of Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions

5.1. Fibroblast–Immune Cell Interaction Mechanisms

5.2. Impact of ECM Remodeling on Regeneration and Immune Cell Recruitment

5.3. Physiological Impact of pH and Acidic Microenvironments

5.4. Immune Cell-Derived Signals and Fibroblast Function

5.5. Role of Key Proteins (MMPs, Growth Factors, Chemokines)

| Fibroblast Interaction Partner | Specific Examples of Interaction | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Cells | ||

| Macrophages | M1 macrophages promote fibroblast activation and ECM degradation; M2 macrophages secrete TGF-β to induce fibroblast proliferation and wound healing via AKT, ERK1/2, STAT3 pathways | [7] |

| T Cells | Fibroblasts interact with T cells via human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA-II), modulating helper T cell 1/2 (Th1/Th2) balance; Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13) promote fibroblast transition to myofibroblasts enhancing fibrosis | |

| ECM | Fibroblast-deposited collagen increases ECM stiffness guiding macrophage migration; fibronectin fragments act as immune cell activators | [77,78] |

| pH and Metabolic Factors | Acidic microenvironment promotes fibroblast pro-fibrotic phenotype; low pH modulates MMP activity affecting ECM remodeling; lactate influences macrophage M2 polarization | [79,80] |

| Signaling Proteins | ||

| Growth Factors | PDGF-D enhances cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration; FGF and TGF-β regulate fibroblast–myofibroblast differentiation crucial for tissue repair | [54,83,84] |

| Chemokines | Fibroblast-produced CCL2 recruits monocytes/macrophages; CXCL12 attracts hematopoietic stem cells and lymphocytes facilitating regeneration and immune cell organization |

6. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Fibroblast–Immune Microenvironment Interactions for Enhanced Tissue Regeneration

6.1. Modulation of Fibroblast–Immune Crosstalk

6.2. Regulation of ECM–Fibroblast Signaling Network

6.3. Targeting Physicochemical Microenvironmental Factors

6.4. Growth Factor and Chemokine Signaling–Mediated Regulation of Fibroblast Function

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldman, J.A.; Poss, K.D. Gene regulatory programmes of tissue regeneration. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Liu, Y. The role of the immune microenvironment in bone regeneration. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 3697–3707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Man, M.-Q.; Hu, L. Aging in the dermis: Fibroblast senescence and its significance. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, N.; Takayanagi, H. Mechanisms of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis—Immune cell–fibroblast–bone interactions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, M.; Quinn, S.M.; Fearon, U.; Ansboro, S.; Rakovic, T.; Southern, J.M.; Kelly, V.P.; Connon, S.J. A new class of 7-deazaguanine agents targeting autoimmune diseases: Dramatic reduction of synovial fibroblast IL-6 production from human rheumatoid arthritis patients and improved performance against murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felisbino, M.B.; Rubino, M.; Travers, J.G.; Schuetze, K.B.; Lemieux, M.E.; Anseth, K.S.; Aguado, B.A.; McKinsey, T.A. Substrate stiffness modulates cardiac fibroblast activation, senescence, and proinflammatory secretory phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H61–H73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Gallegos, D.; Jiang, D.; Rinkevich, Y. Fibroblasts as confederates of the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2021, 302, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.; Coles, M.; Thomas, T.; Kollias, G.; Ludewig, B.; Turley, S.; Brenner, M.; Buckley, C.D. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.X.; Yu, Q.Y.; Tang, X.X. Role of interleukins in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, N.; Golin, A.P.; Jalili, R.B.; Ghahary, A. Roles of cutaneous cell-cell communication in wound healing outcome: An emphasis on keratinocyte-fibroblast crosstalk. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Yu, J.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Guo, K.; Qing, R.; Wang, G.; Ren, J. Micro-gel ensembles for accelerated healing of chronic wound via pH regulation. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2201254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbandhu, V.; Tallapragada, V.; Patrick, R.; Li, Y.; Abeygunawardena, D.; Humphreys, D.T.; Martin, E.M.M.A.; Ward, A.O.; Contreras, O.; Farbehi, N.; et al. Hif-1a suppresses ROS-induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts following myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 281–297.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, T.; Ahmed, A.; Rognoni, E. Fibroblast memory in development, homeostasis and disease. Cells 2021, 10, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, H.E.; Mascharak, S.; Griffin, M.; Wan, D.C.; Longaker, M.T. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1161–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lou, Y.; Hong, Z.; Wei, S.; Sun, K.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Sheng, J.; et al. Dynamic profiling of immune microenvironment during pancreatic cancer development suggests early intervention and combination strategy of immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 2022, 78, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antinozzi, C.; Sgrò, P.; Marampon, F.; Caporossi, D.; Del Galdo, F.; Dimauro, I.; Di Luigi, L. Sildenafil counteracts the in vitro activation of CXCL-9, CXCL-10 and CXCL-11/CXCR3 axis induced by reactive oxygen species in scleroderma fibroblasts. Biology 2021, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baima, G.; Arce, M.; Romandini, M.; Van Dyke, T. Inflammatory and Immunological Basis of Periodontal Diseases. J. Periodontal Res. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I.; Wei, K.; Pohin, M.; Kim, E.Y.; Barone, F.; Major, T.; Taylor, E.; Ravindran, R.; Kemble, S.; Watts, G.F.; et al. Cross-tissue, single-cell stromal atlas identifies shared pathological fibroblast phenotypes in four chronic inflammatory diseases. Med 2022, 3, 481–518.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kumar, D.S.; Nitta, R.K.; Rani, M.H.S.; Gajbhiye, N. Understanding the influence of tumour microenvironment variability on therapeutic effectiveness. Int. J. Trends OncoSci. 2024, 5, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.-C.; Voß, L.; Schwerdt, G.; Gekle, M. Epithelial–Fibroblast Crosstalk Protects against Acidosis-Induced Inflammatory and Fibrotic Alterations. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Molley, T.G.; Jalandhra, G.K.; Fang, J.; Kruzic, J.J.; Kilian, K.A. Magnetoactive Nanotopography on Hydrogels for Stimulated Cell Adhesion and Differentiation. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2400468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.-D.; Gao, J.; Tang, A.-F.; Feng, C. Shaping the immune landscape: Multidimensional environmental stimuli refine macrophage polarization and foster revolutionary approaches in tissue regeneration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e03172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.M.; Xie, W.M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.M.; Zhan, Y.; Wu, X.D.; Dai, Y.X.; Pei, Y.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, G.X. Chitosan scaffolds for bone applications: A detailed review of main types, features and multifaceted uses. Eur. Cells Mater. 2025, 52, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Sánchez, N.; Alonso-Alonso, S.; Nagy, L. Regenerative inflammation: When immune cells help to re-build tissues. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qu, Y.; Chu, B.; Wu, T.; Pan, M.; Mo, D.; Li, L.; Ming, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Research progress on biomaterials with immunomodulatory effects in bone regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e01209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.T.; Henao Agudelo, J.S.; Camara, N.O.S. Macrophages during the fibrotic process: M2 as friend and foe. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurora, A.B.; Olson, E.N. Immune modulation of stem cells and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurts, C.; Ginhoux, F.; Panzer, U. Kidney dendritic cells: Fundamental biology and functional roles in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Bose, B. A snapshot of cytokine dynamics: A fine balance between health and disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 126, e30680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenin-Mace, L.; Konieczny, P.; Naik, S. Immune-epithelial cross talk in regeneration and repair. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 41, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdoz, J.C.; Johnson, B.C.; Jacobs, D.J.; Franks, N.A.; Dodson, E.L.; Sanders, C.; Cribbs, C.G.; Van Ry, P.M. The ECM: To scaffold, or not to scaffold, that is the question. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farach-Carson, M.C.; Wu, D.; França, C.M. Proteoglycans in mechanobiology of tissues and organs: Normal functions and mechanopathology. Proteoglycan Res. 2024, 2, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zheng, L.; Yuan, Q.; Zhen, G.; Crane, J.L.; Zhou, X.; Cao, X. Transforming growth factor-β in stem cells and tissue homeostasis. Bone Res. 2018, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vizely, K.; Li, C.Y.; Shen, K.; Shakeri, A.; Khosravi, R.; Smith, J.R.; Alteza, E.A.I.I.; Zhao, Y.; Radisic, M. Biomaterials for immunomodulation in wound healing. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, M.M.; Abohashema, D.M.; Abdelwahab, M.S.; Fayed, M.T.; Ghanem, A.; Mohamed, O.A.A. The Role of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) in Wound Healing (IE, Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Growth Factors). In Nanotechnology in Wound Healing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 124–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kalli, M.; Poskus, M.D.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Zervantonakis, I.K. Beyond matrix stiffness: Targeting force-induced cancer drug resistance. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 937–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Manon-Jensen, T.; Genovese, F.; Kristensen, J.H.; Nielsen, M.J.; Sand, J.M.B.; Hansen, N.U.B.; Bay-Jensen, A.C.; Bager, C.L.; Krag, A.; et al. Novel insights into the function and dynamics of extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 308, G807–G830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.; Duda, G.N.; Sass, F.A.; Dienelt, A. The metabolic microenvironment steers bone tissue regeneration. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjar, S.; Zhou, X. pH sensing at the intersection of tissue homeostasis and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasciglione, G.F.; Marini, S.; D’Alessio, S.; Politi, V.; Coletta, M. pH-and temperature-dependence of functional modulation in metalloproteinases. A comparison between neutrophil collagenase and gelatinases A and B. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureka, N.; Zaheer, S. Regulatory T Cells in Tumor Microenvironment: Therapeutic Approaches and Clinical Implications. Cell Biol. Int. 2025, 49, 897–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S.; Stojadinovic, O.; Golinko, M.S.; Brem, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: Signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdai, F.; Risaliti, C.; Monici, M. Role of fibroblasts in wound healing and tissue remodeling on Earth and in space. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 958381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Z.Y.; Nee, E.; Coles, M.; Buckley, C.D. Why does understanding the biology of fibroblasts in immunity really matter? PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3001954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F. The role of mechanotransduction in contact inhibition of locomotion and proliferation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdroudi, F.B.; Malek, A. Optimal controlling of anti-TGF-β and anti-PDGF medicines for preventing pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Lu, Z.; Su, J.; Qian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Song, S.; Hang, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, F. ASIC1a promotes the proliferation of synovial fibroblasts via the ERK/MAPK pathway. Lab. Investig. 2021, 101, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, T.; Yadu, H.; Sahu, P. Protective Role of Herbal Bioactive in Modulation of PDGF-VEGF-TGFβ-EGF Fibroblast Proliferation and Re-epithelialization for the Enhancement of Tissue Strength and Wound Healing. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čoma, M.; Fröhlichová, L.; Urban, L.; Zajíček, R.; Urban, T.; Szabo, P.; Novák, Š.; Fetissov, V.; Dvořánková, B.; Smetana, K.; et al. Molecular changes underlying hypertrophic scarring following burns involve specific deregulations at all wound healing stages (inflammation, proliferation and maturation). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Lin, Q.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, J.J.; Xing, D. Fibroblast–Myofibroblast Transition in Osteoarthritis Progression: Current Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wen, D.; Xu, X.; Zhao, R.; Jiang, F.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q. Extracellular matrix stiffness—The central cue for skin fibrosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1132353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bartleson, J.M.; Butenko, S.; Alonso, V.; Liu, W.F.; Winer, D.A.; Butte, M.J. Tuning immunity through tissue mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, F.S.; Miller, A.E.; Barker, T.H.; Rossi, F.M.V.; Hinz, B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 617–638, Correction in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Theocharis, A.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Manou, D.; Passi, A.; Skandalis, S.S.; Vynios, D.H.; Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ricard-Blum, S.; Schmelzer, C.E.; et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6850–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naba, A. Mechanisms of assembly and remodelling of the extracellular matrix. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarte David, V.A.; Güiza-Argüello, V.R.; Arango-Rodríguez, M.L.; Sossa, C.L.; Becerra-Bayona, S.M. Decellularized tissues for wound healing: Towards closing the gap between scaffold design and effective extracellular matrix remodeling. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 821852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Sahel, D.; Kubal, B.; Postwala, H.; Shah, Y.; Chavda, V.P.; Fernandes, C.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Role of the extracellular matrix in cancer: Insights into tumor progression and therapy. Adv. Ther. 2025, 8, 2400370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Murray, P.J.; Pearce, E.J. Metabolic orchestration of the wound healing response. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1726–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalyte, R.; Denkovskij, J.; Bernotiene, E.; Stropuviene, S.; Mikulenaite, S.O.; Kvederas, G.; Porvaneckas, N.; Tutkus, V.; Venalis, A.; Butrimiene, I. The expression of inflammasomes NLRP1 and NLRP3, toll-like receptors, and vitamin D receptor in synovial fibroblasts from patients with different types of knee arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 767512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellevik, T.; Berzaghi, R.; Lode, K.; Islam, A.; Martinez-Zubiaurre, I. Immunobiology of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the context of radiotherapy. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Cui, Y.; Han, H.; Guo, E.; Shi, X.; Xiong, K.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, S.; Sang, S.; Liu, M.; et al. Fibroblast atlas: Shared and specific cell types across tissues. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eado0173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L.; Olabi, B.; Roberts, K.; Mazin, P.V.; Koplev, S.; Tudor, C.; Rumney, B.; Admane, C.; Jiang, T.; Correa-Gallegos, D.; et al. A single-cell and spatial genomics atlas of human skin fibroblasts reveals shared disease-related fibroblast subtypes across tissues. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 1807–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T. Dermal fibroblast subsets and their roles in inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2025, 120, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsthuber, A.; Aschenbrenner, B.; Korosec, A.; Jacob, T.; Annusver, K.; Krajic, N.; Kholodniuk, D.; Frech, S.; Zhu, S.; Purkhauser, K.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment and are associated with skin cancer malignancy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Debnath, R.; Chikelu, I.; Zhou, J.X.; Ko, K.I. Primed inflammatory response by fibroblast subset is necessary for proper oral and cutaneous wound healing. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2024, 39, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, C.J.; Waise, S.; Ellis, M.J.; Lopez, M.A.; Pun, W.Y.; Taylor, J.; Parker, R.; Kimbley, L.M.; Chee, S.J.; Shaw, E.C.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals prognostic fibroblast subpopulations linked to molecular and immunological subtypes of lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Fibroblast activation and heterogeneity in fibrotic disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Mhaidly, R.; Croizer, H.; Kieffer, Y.; Leclere, R.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Robley, C.; Anglicheau, D.; Rabant, M.; Sannier, A.; et al. WNT-dependent interaction between inflammatory fibroblasts and FOLR2+ macrophages promotes fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidereit, E.M.; Mavrommatis, L.; Kuppe, C. Cell–cell crosstalk in kidney health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Injury-induced Clusterin+ cardiomyocytes suppress inflammation and promote regeneration in neonatal and adult hearts by reprogramming macrophages. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 136, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, S.; Qin, J.; Tao, B.; Thomas, N.E.; Cao, E.; Wu, R.; Sandoval, D.R.; Piermatteo, A.; Grunddal, K.V.; Ma, F.; et al. Bone-marrow macrophage-derived GPNMB protein binds to orphan receptor GPR39 and plays a critical role in cardiac repair. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 1356–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarig, R.; Tzahor, E. Fibroblast signaling is required for cardiac regeneration. Nature 2024, 3, 897–898. [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, F.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Massey, W.J.; Wang, Y.; Fiocchi, C. Fibrosis in IBD: From pathogenesis to therapeutic targets. Gut 2024, 73, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Typiak, M.; Żurawa-Janicka, D. Not an immune cell, but they may act like one—Cells with immune properties outside the immune system. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2024, 102, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Ren, Y.; Liu, S.; Ba, Y.; Zuo, A.; Luo, P.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, H.; Han, X. Multi-stage mechanisms of tumor metastasis and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, E.J.; Paterson, K.; Riera-Domingo, C.; Sumpton, D.; Däbritz, J.H.M.; Tardito, S.; Boldrini, C.; Hernandez-Fernaud, J.R.; Athineos, D.; Dhayade, S.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts require proline synthesis by PYCR1 for the deposition of pro-tumorigenic extracellular matrix. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, M.; Nizamoglu, M.; Kaper, H.J.; Brouwer, L.A.; Borghuis, T.; Burgess, J.K.; Harmsen, M.C.; Sharma, P.K. Fibroblast alignment and matrix remodeling induced by a stiffness gradient in a skin-derived extracellular matrix hydrogel. Acta Biomater. 2024, 182, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, C.; Shen, A.N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R. pH of Microenvironment Directly Modulates the Phenotype and Function of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 3937–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Do, H.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, W. Impact of chlorogenic acid on modulation of significant genes in dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 583, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerneur, C.; Cano, C.E.; Olive, D. Major pathways involved in macrophage polarization in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J.; Hsieh, M.-S.; Chang, G.-C.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-M.; Chen, Y.-L.; Yang, P.-C.; Yu, S.-L. Tp53 determines the spatial dynamics of M1/M2 tumor-associated macrophages and M1-driven tumoricidal effects. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhartha, R.; Goel, A.; Singhai, A.; Garg, M. Matrix metalloproteinases-2 and-9, vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor and CD105-micro-vessel density are predictive markers of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and muscle invasive bladder cancer subtypes. Biochem. Genet. 2025, 63, 4057–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, A.E.; Kongthong, S.; Mueller, A.A.; Brenner, M.B. Fibroblasts in immune responses, inflammatory diseases and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Yuan, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, N. Tissue regeneration: Unraveling strategies for resolving pathological fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiam, F.; Phogat, S.; Abokor, F.A.; Osei, E.T. In vitro co-culture studies and the crucial role of fibroblast-immune cell crosstalk in IPF pathogenesis. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Guan, L.; Wang, C.; Hu, R.; Ou, L.; Jiang, Q. The role of fibroblast-neutrophil crosstalk in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases: A multi-tissue perspective. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1588667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Cheng, W.; Diao, T.; Liu, H.; Bo, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Cross-tissue human fibroblast atlas reveals myofibroblast subtypes with distinct roles in immune modulation. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1764–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setten, E.; Castagna, A.; Nava-Sedeño, J.M.; Weber, J.; Carriero, R.; Reppas, A.; Volk, V.; Schmitz, J.; Gwinner, W.; Hatzikirou, H.; et al. Understanding fibrosis pathogenesis via modeling macrophage-fibroblast interplay in immune-metabolic context. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, S.-H.; Shin, K. Crosstalk between fibroblasts and T cells in immune networks. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F. Strategies for targeting cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.; Hernaez-Estrada, B.; Hernandez, R.M.; Santos-Vizcaino, E.; Spiller, K.L. Immunomodulatory biomaterials for tissue repair. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11305–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Lin, C.; Tao, B.; Deng, Z.; Gao, P.; Yang, Y.; Cai, K. A pH-responsive hyaluronic acid hydrogel for regulating the inflammation and remodeling of the ECM in diabetic wounds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 2875–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Luo, Q.; Yang, Y.; Shao, N.; Nie, T.; Deng, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Hu, K.; et al. Injectable pH Responsive Conductive Hydrogel for Intelligent Delivery of Metformin and Exosomes to Enhance Cardiac Repair after Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2410590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siani, A.; Infante-Teixeira, L.; d’Arcy, R.; Roberts, I.V.; El Mohtadi, F.; Donno, R.; Tirelli, N. Polysulfide nanoparticles inhibit fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via extracellular ROS scavenging and have potential anti-fibrotic properties. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 153, 213537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharaziha, M.; Salehi, S.; Shokri, M.; Ahmadi Tafti, S.M.; Scheibel, T. ROS-Scavenging Multifunctional Microneedle Patch Facilitating Wound Healing. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2025, 14, e01886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q.; Cai, J.; Yu, B.; Dai, Q.; Bao, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.; et al. Glucocorticoid-loaded pH/ROS dual-responsive nanoparticles alleviate joint destruction by down-regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Acta Biomater. 2023, 164, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Saengow, C.; Ju, L.; Ren, W.; Ewoldt, R.H.; Irudayaraj, J. Exosome-coated oxygen nanobubble-laden hydrogel augments intracellular delivery of exosomes for enhanced wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Belly, H.; Paluch, E.K.; Chalut, K.J. Interplay between mechanics and signalling in regulating cell fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Li, T.; Liao, B. Targeting fibrosis: From molecular mechanisms to advanced therapies. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2410416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, C.; Chen, X. Designing hydrogels for immunomodulation in cancer therapy and regenerative medicine. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2308894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.A.; Sato, Y.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Harashima, H. Reprogramming activated hepatic stellate cells by siRNA-loaded nanocarriers reverses liver fibrosis in mice. J. Control. Release 2023, 361, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chogan, F.; Mirmajidi, T.; Rezayan, A.H.; Sharifi, A.M.; Ghahary, A.; Nourmohammadi, J.; Kamali, A.; Rahaie, M. Design, fabrication, and optimization of a dual function three-layer scaffold for controlled release of metformin hydrochloride to alleviate fibrosis and accelerate wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Son, B. Regulation of Tissue Regeneration by Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411950

Son B. Regulation of Tissue Regeneration by Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411950

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Boram. 2025. "Regulation of Tissue Regeneration by Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411950

APA StyleSon, B. (2025). Regulation of Tissue Regeneration by Immune Microenvironment–Fibroblast Interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411950