Beyond Viral Assembly: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 p17 in Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) p17 Biology and Secretion

3. Extracellular Activities of p17

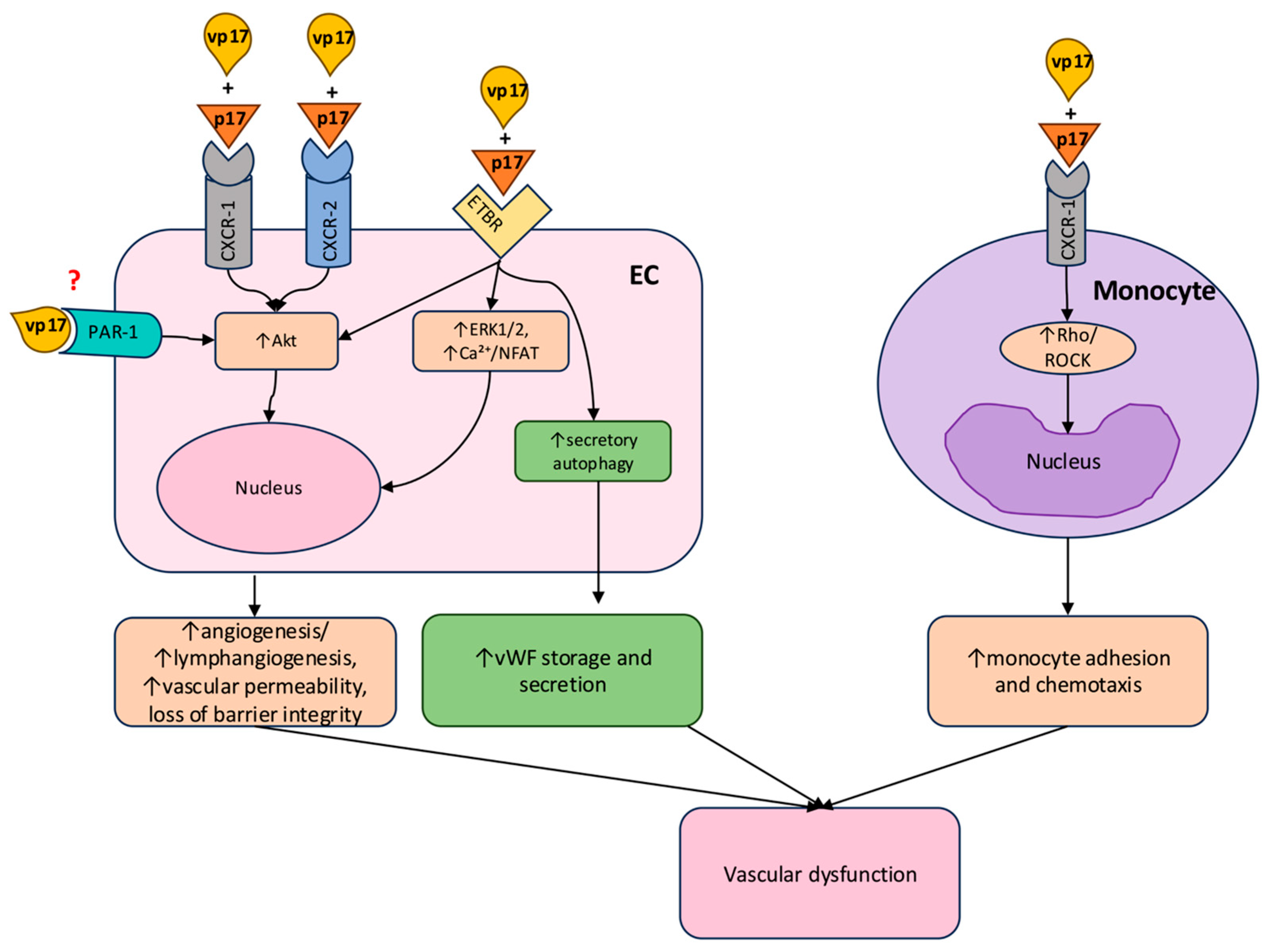

4. Potential Mechanisms of p17-Induced Vascular Damage

4.1. Endothelial Activation and Proangiogenic and Lymphangiogenic Modulation

4.2. Pro-Thrombotic Effects

4.3. Tumorigenic Effects

4.4. Systemic Pro-Inflammatory Signaling

4.5. Neuroinflammatory Signatures

5. Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) and Vascular Function in Chronic HIV-1 Infection

6. Comparative Roles of Other HIV-1 Proteins on Endothelial Dysfunction and Neuroinflammation: Tat and Nef

6.1. Tat

6.2. Nef

7. Therapeutic Implications: Could Targeting p17 Reduce Vascular Comorbidities?

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| cART | Combined antiretroviral therapy |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CXCR-1/2 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor-1/2 |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| EC | Endothelial cell |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| EV | Extracellular vesicles |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| GC | Germinal center |

| HAND | HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders |

| HbEC | Human brain endothelial cell |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| HLMVEC | Human lung microvascular endothelial cell |

| HPAEC | Human pulmonary artery endothelial cell |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity CRP |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vein endothelial cell |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule- |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IMT | Intima-media thickness |

| IRIS | Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome |

| LN-LEC | Lymph node-derived lymphatic endothelial cell |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MBP | Myelin basic protein |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MGC | Multinucleated giant cells |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| Nef | Negative regulatory factor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NHL | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| NNRTI | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| Nox-1 | NADPH oxidase 1 |

| NRTI | Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| p17R | p17 receptor |

| PAF | Platelet-activating factor |

| PAR-1 | Protease-activated receptor 1 |

| PI | Protease inhibitor |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase |

| PLC-γ1 | Phospholipase C-gamma 1 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| p-tau | Phosphorylated tau |

| ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Ser/Thr | Serin/Threonin |

| Tat | Trans-activator of transcription |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion protein-1 |

| vp17 | p17 variants |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| vWF | Von Willebrand factor |

References

- Williams, A.; Menon, S.; Crowe, M.; Agarwal, N.; Biccler, J.; Bbosa, N.; Ssemwanga, D.; Adungo, F.; Moecklinghoff, C.; Macartney, M.; et al. Geographic and Population Distributions of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 Circulating Subtypes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis (2010–2021). J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonaguro, L.; Tornesello, M.L.; Buonaguro, F.M. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Subtype Distribution in the Worldwide Epidemic: Pathogenetic and Therapeutic Implications. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10209–10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinstein, M.J. HIV and Cardiovascular Disease: From Insights to Interventions. Top. Antivir. Med. 2021, 29, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ntsekhe, M.; Baker, J.V. Cardiovascular Disease Among Persons Living With HIV: New Insights Into Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations in a Global Context. Circulation 2023, 147, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șoldea, S.; Iovănescu, M.; Berceanu, M.; Mirea, O.; Raicea, V.; Beznă, M.C.; Rocșoreanu, A.; Donoiu, I. Cardiovascular Disease in HIV Patients: A Comprehensive Review of Current Knowledge and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, K.; Nqebelele, U.; Murray, L.; Thomas, T.S.; Mpanya, D.; Tsabedze, N. Cardiac and Renal Comorbidities in Aging People Living With HIV. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1636–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Duan, W.; Ma, X.; Guan, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Tian, T.; et al. Higher Cardiovascular Disease Risks in People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.; Kwok, M.; Boucher, K.-A.; Haji, M.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Longenecker, C.T.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Ross, D.; Jutkowtiz, E.; Sullivan, J.L.; et al. Performance of Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Models Among People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbune, M.; Plesea-Condratovici, A.; Arbune, A.-A.; Andronache, G.; Plesea-Condratovici, C.; Gutu, C. Cardiovascular Risk in People Living with HIV: A Preliminary Case Study from Romania. Medicina 2025, 61, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Rodriguez, L.; Sahrmann, J.M.; Butler, A.M.; Olsen, M.A.; Powderly, W.G.; O’Halloran, J.A. Antiretroviral Therapy and Cardiovascular Risk in People with HIV in the United States—An Updated Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccuri, F.; Rueckert, C.; Giagulli, C.; Schulze, K.; Basta, D.; Zicari, S.; Marsico, S.; Cervi, E.; Fiorentini, S.; Slevin, M.; et al. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Promotes Lymphangiogenesis and Activates the Endothelin-1/Endothelin B Receptor Axis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccuri, F.; Messali, S.; Zani, A.; Campisi, G.; Giovanetti, M.; Zanussi, S.; Vaccher, E.; Fabris, S.; Bugatti, A.; Focà, E.; et al. HIV-1 Mutants Expressing B Cell Clonogenic Matrix Protein P17 Variants Are Increasing Their Prevalence Worldwide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2122050119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Lin, F.; Guo, R.; Wu, D.; Shen, R.; Harypursat, V.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17: A Key Factor in HIV-Associated Cancers. Front. Virol. 2025, 5, 1584507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccuri, F.; Iaria, M.L.; Campilongo, F.; Varney, K.; Rossi, A.; Mitola, S.; Schiarea, S.; Bugatti, A.; Mazzuca, P.; Giagulli, C.; et al. Cellular Aspartyl Proteases Promote the Unconventional Secretion of Biologically Active HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O. HIV-1 Assembly, Release and Maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Huan, C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Zheng, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. NF-κB-Interacting Long Noncoding RNA Regulates HIV-1 Replication and Latency by Repressing NF-κB Signaling. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugatti, A.; Caccuri, F.; Filippini, F.; Ravelli, C.; Caruso, A. Binding to PI(4,5)P2 Is Indispensable for Secretion of B-Cell Clonogenic HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Variants. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.; Behrens-Bradley, N.; Ahmad, A.; Wertheimer, A.; Klotz, S.; Ahmad, N. Plasma Levels of Secreted Cytokines in Virologically Controlled HIV-Infected Aging Adult Individuals on Long-Term Antiretroviral Therapy. Viral Immunol. 2024, 37, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagulli, C.; Caccuri, F.; Zorzan, S.; Bugatti, A.; Zani, A.; Filippini, F.; Manocha, E.; D’Ursi, P.; Orro, A.; Dolcetti, R.; et al. B-Cell Clonogenic Activity of HIV-1 P17 Variants Is Driven by PAR1-Mediated EGF Transactivation. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motozono, C.; Mwimanzi, P.; Ueno, T. Dynamic Interplay between Viral Adaptation and Immune Recognition during HIV-1 Infection. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Yau, S.S.-T. In-Depth Investigation of the Point Mutation Pattern of HIV-1. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1033481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, D.; Song, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, A.; Xu, J.; Guo, W.; Wu, M.; Shi, Y.; et al. High Expression of HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 in Both Lymphoma and Lymph Node Tissues of AIDS Patients. Pathol.-Res. Pract. 2022, 237, 154061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giagulli, C.; Marsico, S.; Magiera, A.K.; Bruno, R.; Caccuri, F.; Barone, I.; Fiorentini, S.; Andò, S.; Caruso, A. Opposite Effects of HIV-1 P17 Variants on PTEN Activation and Cell Growth in B Cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Francesco, M.A.; Baronio, M.; Fiorentini, S.; Signorini, C.; Bonfanti, C.; Poiesi, C.; Popovic, M.; Grassi, M.; Garrafa, E.; Bozzo, L.; et al. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Increases the Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Counteracts IL-4 Activity by Binding to a Cellular Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9972–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.-H.; Liu, L.-Z. PI3K/PTEN Signaling in Tumorigenesis and Angiogenesis. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2008, 1784, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Tiberio, L.; Caracciolo, S.; Tosti, G.; Guzman, C.A.; Schiaffonati, L.; Fiorentini, S.; Caruso, A. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Binds to Monocytes and Selectively Stimulates MCP-1 Secretion: Role of Transcriptional Factor AP-1. Cell Microbiol. 2008, 10, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagulli, C.; Magiera, A.K.; Bugatti, A.; Caccuri, F.; Marsico, S.; Rusnati, M.; Vermi, W.; Fiorentini, S.; Caruso, A. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Binds to the IL-8 Receptor CXCR1 and Shows IL-8–like Chemokine Activity on Monocytes through Rho/ROCK Activation. Blood 2012, 119, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, C.L.; Daniel, T.O.; Burdick, M.D.; Liu, H.; Ehlert, J.E.; Xue, Y.Y.; Buechi, L.; Walz, A.; Richmond, A.; Strieter, R.M. The CXC Chemokine Receptor 2, CXCR2, Is the Putative Receptor for ELR+ CXC Chemokine-Induced Angiogenic Activity. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 5269–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccuri, F.; Giagulli, C.; Bugatti, A.; Benetti, A.; Alessandri, G.; Ribatti, D.; Marsico, S.; Apostoli, P.; Slevin, M.A.; Rusnati, M.; et al. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Promotes Angiogenesis via Chemokine Receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14580–14585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, D.; Latinovic, O.; Lafferty, M.K.; Sun, L.; Bryant, J.; Lu, W.; Caccuri, F.; Caruso, A.; Gallo, R.; Garzino-Demo, A. Angiogenic, Lymphangiogenic and Adipogenic Effects of HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17. Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, ftv062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D.; Ushiyama, A.; Duda, D.G.; Xu, L.; Tam, J.; Krishna, V.; Chatterjee, K.; Garkavtsev, I.; Jain, R.K. Paracrine Regulation of Angiogenesis and Adipocyte Differentiation During In Vivo Adipogenesis. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, e88–e97, Erratum in Circ. Res. 2004, 94, e16; Erratum in Circ. Res. 2005, 96, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merfeld-Clauss, S.; Gollahalli, N.; March, K.L.; Traktuev, D.O. Adipose Tissue Progenitor Cells Directly Interact with Endothelial Cells to Induce Vascular Network Formation. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 2953–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zeinolabediny, Y.; Caccuri, F.; Ferris, G.; Fang, W.-H.; Weston, R.; Krupinski, J.; Colombo, L.; Salmona, M.; Corpas, R.; et al. P17 from HIV Induces Brain Endothelial Cell Angiogenesis through EGFR-1-Mediated Cell Signalling Activation. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugatti, A.; Marsico, S.; Mazzuca, P.; Schulze, K.; Ebensen, T.; Giagulli, C.; Peña, E.; Badimón, L.; Slevin, M.; Caruso, A.; et al. Role of Autophagy in Von Willebrand Factor Secretion by Endothelial Cells and in the In Vivo Thrombin-Antithrombin Complex Formation Promoted by the HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torisu, T.; Torisu, K.; Lee, I.H.; Liu, J.; Malide, D.; Combs, C.A.; Wu, X.S.; Rovira, I.I.; Fergusson, M.M.; Weigert, R.; et al. Autophagy Regulates Endothelial Cell Processing, Maturation and Secretion of von Willebrand Factor. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Tan, H.-L.; Shui, G.; Bauvy, C.; Huang, Q.; Wenk, M.R.; Ong, C.-N.; Codogno, P.; Shen, H.-M. Dual Role of 3-Methyladenine in Modulation of Autophagy via Different Temporal Patterns of Inhibition on Class I and III Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 10850–10861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M.; Tenner-Racz, K.; Pelser, C.; Stellbrink, H.-J.; Van Lunzen, J.; Lewis, G.; Kalyanaraman, V.S.; Gallo, R.C.; Racz, P. Persistence of HIV-1 Structural Proteins and Glycoproteins in Lymph Nodes of Patients under Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14807–14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcetti, R.; Giagulli, C.; He, W.; Selleri, M.; Caccuri, F.; Eyzaguirre, L.M.; Mazzuca, P.; Corbellini, S.; Campilongo, F.; Marsico, S.; et al. Role of HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Variants in Lymphoma Pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 14331–14336, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccuri, F.; Muraro, E.; Gloghini, A.; Turriziani, O.; Riminucci, M.; Giagulli, C.; Mastorci, K.; Fae’, D.A.; Fiorentini, S.; Caruso, A.; et al. Lymphomagenic Properties of a HIV P17 Variant Derived from a Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma Occurred in a HIV-infected Patient. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 37, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorelli, D.; Muraro, E.; Mastorci, K.; Dal Col, J.; Faè, D.A.; Furlan, C.; Giagulli, C.; Caccuri, F.; Rusnati, M.; Fiorentini, S.; et al. A Natural HIV P17 Protein Variant Up-Regulates the LMP-1 EBV Oncoprotein and Promotes the Growth of EBV-Infected B-Lymphocytes: Implications for EBV-Driven Lymphomagenesis in the HIV Setting: HIV P17 and EBV-Driven Lymphomagenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, D.R.; Hullsiek, K.H.; Puronen, C.E.; Rupert, A.; Baker, J.V.; French, M.A.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Novak, R.M.; Neaton, J.D.; Sereti, I. Higher Levels of CRP, D-Dimer, IL-6, and Hyaluronic Acid Before Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Are Associated with Increased Risk of AIDS or Death. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, B.O.; Ouedraogo, G.L.; Hodge, J.N.; Smith, M.A.; Pau, A.; Roby, G.; Kwan, R.; Bishop, R.J.; Rehm, C.; Mican, J.; et al. D-Dimer and CRP Levels Are Elevated Prior to Antiretroviral Treatment in Patients Who Develop IRIS. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 136, 42–50, Erratum in Clin. Immunol. 2010, 136, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, A.J.; Fox, Z.; Lundgren, J.D.; Kuller, L.H.; Boesecke, C.; Gey, D.; Skoutelis, A.; Goetz, M.B.; Phillips, A.N. The INSIGHT Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) Study Group. Activation and Coagulation Biomarkers Are Independent Predictors of the Development of Opportunistic Disease in Patients with HIV Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, B. C-Reactive Protein Is a Marker for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease Progression. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccuri, F.; Neves, V.; Gano, L.; Correia, J.D.G.; Oliveira, M.C.; Mazzuca, P.; Caruso, A.; Castanho, M. The HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Does Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e01200-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinolabediny, Y.; Caccuri, F.; Colombo, L.; Morelli, F.; Romeo, M.; Rossi, A.; Schiarea, S.; Ciaramelli, C.; Airoldi, C.; Weston, R.; et al. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Misfolding Forms Toxic Amyloidogenic Assemblies That Induce Neurocognitive Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budka, H. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Envelope and Core Proteins in CNS Tissues of Patients with the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Acta Neuropathol. 1990, 79, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geny, C.; Gherardi, R.; Boudes, P.; Lionnet, F.; Cesaro, P.; Gray, F. Multifocal Multinucleated Giant Cell Myelitis in an AIDS Patient. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1991, 17, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, P.; Vago, L.; Mengozzi, M.; Torri, V.; Ceresa, D.; Vicenzi, E.; Transidico, P.; Vagani, A.; Sozzani, S.; Mantovani, A.; et al. Elevated Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1 Correlate with HIV-1 Encephalitis and Local Viral Replication. AIDS 1998, 12, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, K.; Garzino-Demo, A.; Nath, A.; McArthur, J.C.; Halliday, W.; Power, C.; Gallo, R.C.; Major, E.O. Induction of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 in HIV-1 Tat-Stimulated Astrocytes and Elevation in AIDS Dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3117–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsch, O.; Oh, J.-W.; Nath, A.; Benveniste, E.N. Induction of the Chemokines Interleukin-8 and IP-10 by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Tat in Astrocytes. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 9214–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, B.R.; Lore, K.; Bock, P.J.; Andersson, J.; Coffey, M.J.; Strieter, R.M.; Markovitz, D.M. Interleukin-8 Stimulates Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Replication and Is a Potential New Target for Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 8195–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.P.; Worthylake, D.; Bancroft, D.P.; Christensen, A.M.; Sundquist, W.I. Crystal Structures of the Trimeric Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Protein: Implications for Membrane Association and Assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 3099–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massiah, M.A.; Starich, M.R.; Paschall, C.; Summers, M.F.; Christensen, A.M.; Sundquist, W.I. Three-Dimensional Structure of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 244, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R.S.; De Oliveira, T.; Seebregts, C.; Danaviah, S.; Gordon, M.; Cassol, S. BioAfrica’s HIV-1 Proteomics Resource: Combining Protein Data with Bioinformatics Tools. Retrovirology 2005, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Hoe, H.-S. EGFR Is a Potential Dual Molecular Target for Cancer and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1238639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.M.; Fawzy, H.M.; El-Khatib, A.S.; Khattab, M.M. Repurposed Anti-Cancer Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors: Mechanisms of Neuroprotective Effects in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemnic, T.; Gulick, P. HIV Antiretroviral Therapy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Weichseldorfer, M.; Reitz, M.; Latinovic, O.S. Past HIV-1 Medications and the Current Status of Combined Antiretroviral Therapy Options for HIV-1 Patients. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.T.; Landovitz, R.J.; Sax, P.E.; Smith, D.M.; Springer, S.A.; Günthard, H.F.; Thompson, M.A.; Bedimo, R.J.; Benson, C.A.; Buchbinder, S.P.; et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV in Adults: 2024 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. JAMA 2025, 333, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, R.M.; Baxter, J.D.; Kim, T.; Marlowe, E.M. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Trends in the Era of Modern Antiretrovirals: 2018–2024. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere, A.; Alonso, R.; Berrocal, L.; Calvo, J.; Foncillas, A.; Chivite, I.; de la Mora, L.; Inciarte, A.; Torres, B.; Martínez-Rebollar, M.; et al. The Role of Protease Inhibitors in HIV Treatment: Who Still Needs Them in 2025? Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 14, 2551–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taramasso, L.; Andreoni, M.; Antinori, A.; Bandera, A.; Bonfanti, P.; Bonora, S.; Borderi, M.; Castagna, A.; Cattelan, A.M.; Celesia, B.M.; et al. Pillars of Long-Term Antiretroviral Therapy Success. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 196, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanmogne, G.D. HIV Infection, Antiretroviral Drugs, and the Vascular Endothelium. Cells 2024, 13, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gaetano Donati, K.; Cauda, R.; Iacoviello, L. HIV Infection, Antiretroviral Therapy and Cardiovascular Risk. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, e2010034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, J.A. Cardiovascular Complications in HIV Management: Past, Present, and Future. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009, 50, 54–64, Erratum in JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009, 51, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Evans, P.C.; Strijdom, H.; Xu, S. HIV Infection, Antiretroviral Therapy and Vascular Dysfunction: Effects, Mechanisms and Treatments. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 217, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.M.M.; Greco, D.B.; Figueiredo, S.M.D.; Fóscolo, R.B.; Oliveira, A.R.D.; Machado, L.J.D.C. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Levels in HIV-Infected Patients Treated or Not with Antiretroviral Drugs and Their Correlation with Factors Related to Cardiovascular Risk and HIV Infection. Atherosclerosis 2008, 201, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhida, S.E.; Mchiza, Z.J.; Mokgalaboni, K.; Hanser, S.; Choshi, J.; Mokoena, H.; Ziqubu, K.; Masilela, C.; Nkambule, B.B.; Ndwandwe, D.E.; et al. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein among People Living with HIV on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Yacovo, S.; Saumoy, M.; Sánchez-Quesada, J.L.; Navarro, A.; Sviridov, D.; Javaloyas, M.; Vila, R.; Vernet, A.; Low, H.; Peñafiel, J.; et al. Lipids, Biomarkers, and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Treatment-Naive HIV Patients Starting or Not Starting Antiretroviral Therapy: Comparison with a Healthy Control Group in a 2-Year Prospective Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.P.; Tibiriçá, E.; Soares, P.P.S.; Benedito, B.; Lima, D.B.; Gomes, M.B.; Farinatti, P.T.V. Assessment of Vascular Function in HIV-Infected Patients. HIV Clin. Trials 2011, 12, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.W.; Stephan, C.; Harmjanz, A.; Staszewski, S.; Buehler, A.; Bickel, M.; Von Kegler, S.; Ruhkamp, D.; Steinmetz, H.; Sitzer, M. Both Long-Term HIV Infection and Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Are Independent Risk Factors for Early Carotid Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2008, 196, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaberg, E.C.; Benning, L.; Sharrett, A.R.; Lazar, J.M.; Hodis, H.N.; Mack, W.J.; Siedner, M.J.; Phair, J.P.; Kingsley, L.A.; Kaplan, R.C. Association between Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Stiffness of the Common Carotid Artery. Stroke 2010, 41, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X. Irreversible Phenotypic Perturbation and Functional Impairment of B Cells during HIV-1 Infection. Front. Med. 2017, 11, 536–547, Erratum in Front. Med. 2019, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.R.; Rachel, G.; Parthasarathy, D. HIV Proteins and Endothelial Dysfunction: Implications in Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Adler, M.; Chen, L.; Kaur, S.; Dhillon, N.K. HIV-Tat and Vascular Endothelium: Implications in the HIV Associated Brain, Heart, and Lung Complications. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1621338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.K.; Lujea, N.C.; Baig, J.; Heath, E.; Nguyen, M.T.; Rodriguez, M.; Campbell, P.; Castro Piedras, I.; Suarez Martinez, E.; Almodovar, S. Differential Effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Nef Variants on Pulmonary Vascular Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chai, L.; Fasae, M.B.; Bai, Y. The Role of HIV Tat Protein in HIV-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, A.; Schietroma, I.; Sernicola, L.; Belli, R.; Campagna, M.; Mancini, F.; Farcomeni, S.; Pavone-Cossut, M.R.; Borsetti, A.; Monini, P.; et al. Role of HIV-1 Tat Protein Interactions with Host Receptors in HIV Infection and Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Nava, B.; Caputi, M. Tat Is a Multifunctional Viral Protein That Modulates Cellular Gene Expression and Functions. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 27569–27581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.P.; Ajasin, D.O.; Ramasamy, S.; DesMarais, V.; Eugenin, E.A.; Prasad, V.R. A Naturally Occurring Polymorphism in the HIV-1 Tat Basic Domain Inhibits Uptake by Bystander Cells and Leads to Reduced Neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.R.; Marino, J.; Dampier, W.; Wigdahl, B.; Nonnemacher, M.R. HIV-1 Tat Length: Comparative and Functional Considerations. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhamija, N.; Choudhary, D.; Ladha, J.S.; Pillai, B.; Mitra, D. Tat Predominantly Associates with Host Promoter Elements in HIV -1-infected T-cells–Regulatory Basis of Transcriptional Repression of c-Rel. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatignol, A.; Duarte, M.; Daviet, L.; Chang, Y.N.; Jeang, K.T. Sequential Steps in Tat Trans-Activation of HIV-1 Mediated through Cellular DNA, RNA, and Protein Binding Factors. Gene Expr. 1996, 5, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Debaisieux, S.; Rayne, F.; Yezid, H.; Beaumelle, B. The Ins and Outs of HIV-1 Tat. Traffic 2012, 13, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritis, M. Endothelial Dysfunction in HIV Infection: Experimental and Clinical Evidence on the Role of Oxidative Stress. Ann. Res. Hosp. 2019, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota-Gomez, A.; Flores, N.C.; Cruz, C.; Casullo, A.; Aw, T.Y.; Ichikawa, H.; Schaack, J.; Scheinman, R.; Flores, S.C. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Tat Protein Activates Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell E-Selectin Expression via an NF-κB-Dependent Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 14390–14399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.; Puri, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Duplan, H.; Masson, J.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1-Tat Protein Induces the Cell Surface Expression of Endothelial Leukocyte Adhesion Molecule-1, Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1, and Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 in Human Endothelial Cells. Blood 1997, 90, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Arese, M.; Ferrandi, C.; Primo, L.; Camussi, G.; Bussolino, F. HIV-1 Tat Protein Stimulates In Vivo Vascular Permeability and Lymphomononuclear Cell Recruitment. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, L.; Bruder-Nascimento, T.; Greene, L.; Kennard, S.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Chronic Exposure to HIV-Derived Protein Tat Impairs Endothelial Function via Indirect Alteration in Fat Mass and Nox1-Mediated Mechanisms in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Ju, S.M.; Seo, W.Y.; Goh, A.R.; Lee, J.-K.; Bae, Y.S.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, J. Nox2-Based NADPH Oxidase Mediates HIV-1 Tat-Induced up-Regulation of VCAM-1/ICAM-1 and Subsequent Monocyte Adhesion in Human Astrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibrand, C.R.; Paris, J.J.; Ghandour, M.S.; Knapp, P.E.; Kim, W.-K.; Hauser, K.F.; McRae, M. HIV-1 Tat Disrupts Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Increases Phagocytic Perivascular Macrophages and Microglia in the Dorsal Striatum of Transgenic Mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 640, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basmaciogullari, S.; Pizzato, M. The Activity of Nef on HIV-1 Infectivity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudt, R.P.; Alvarado, J.J.; Emert-Sedlak, L.A.; Shi, H.; Shu, S.T.; Wales, T.E.; Engen, J.R.; Smithgall, T.E. Structure, Function, and Inhibitor Targeting of HIV-1 Nef-Effector Kinase Complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15158–15171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.-J.; Xie, C.; Li, L.; Jin, X.; Cui, J.; Wang, J.-H. HIV-1 Nef Activates Proviral DNA Transcription by Recruiting Src Kinase to Phosphorylate Host Protein Nef-Associated Factor 1 to Compromise Its Viral Restrictive Function. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0028025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Dash, P.K.; Kumari, T.; Guo, M.; Ghosh, J.K.; Buch, S.J.; Tripathi, R.K. HIV-1 Nef Hijacks Both Exocytic and Endocytic Pathways of Host Intracellular Trafficking through Differential Regulation of Rab GTPases. Biol. Cell 2022, 114, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirk, B.S.; Pawlak, E.N.; Johnson, A.L.; Van Nynatten, L.R.; Jacob, R.A.; Heit, B.; Dikeakos, J.D. HIV-1 Nef Sequesters MHC-I Intracellularly by Targeting Early Stages of Endocytosis and Recycling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, G.; Fagone, P.; Petralia, M.C.; Nicoletti, F.; Basile, M.S. Multifaceted Role of Nef in HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: Histopathological Alterations and Underlying Mechanisms. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Green, L.A.; Gupta, S.K.; Kim, C.; Wang, L.; Almodovar, S.; Flores, S.C.; Prudovsky, I.A.; Jolicoeur, P.; Liu, Z.; et al. Transfer of Intracellular HIV Nef to Endothelium Causes Endothelial Dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelvanambi, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Chen, X.; Ellis, B.W.; Maier, B.F.; Colbert, T.M.; Kuriakose, J.; Zorlutuna, P.; Jolicoeur, P.; Obukhov, A.G.; et al. HIV-Nef Protein Transfer to Endothelial Cells Requires Rac1 Activation and Leads to Endothelial Dysfunction Implications for Statin Treatment in HIV Patients. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, P.; Wang, X.; Lin, P.H.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. HIV Nef Protein Causes Endothelial Dysfunction in Porcine Pulmonary Arteries and Human Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells. J. Surg. Res. 2009, 156, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.; Isidro, R.A.; Loucil-Alicea, R.Y.; Cruz, M.L.; Appleyard, C.B.; Isidro, A.A.; Chompre, G.; Colon-Rivera, K.; Noel, R.J. Infusion of HIV-1 Nef-Expressing Astrocytes into the Rat Hippocampus Induces Enteropathy and Interstitial Pneumonitis and Increases Blood–Brain-Barrier Permeability. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chompre, G.; Cruz, E.; Maldonado, L.; Rivera-Amill, V.; Porter, J.T.; Noel, R.J. Astrocytic Expression of HIV-1 Nef Impairs Spatial and Recognition Memory. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 49, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, J.K.; Karl, M.T.; Clarkson-Paredes, C.; Bastin, A.; Pushkarsky, T.; Brichacek, B.; Miller, R.H.; Bukrinsky, M.I. Extracellular Vesicles Produced by HIV-1 Nef-Expressing Cells Induce Myelin Impairment and Oligodendrocyte Damage in the Mouse Central Nervous System. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentini, S.; Marini, E.; Bozzo, L.; Trainini, L.; Saadoune, L.; Avolio, M.; Pontillo, A.; Bonfanti, C.; Sarmientos, P.; Caruso, A. Preclinical Studies on Immunogenicity of the HIV-1 P17-based Synthetic Peptide AT20-KLH. Biopolymers 2004, 76, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentini, S.; Marsico, S.; Becker, P.D.; Iaria, M.L.; Bruno, R.; Guzmán, C.A.; Caruso, A. Synthetic Peptide AT20 Coupled to KLH Elicits Antibodies against a Conserved Conformational Epitope from a Major Functional Area of the HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17. Vaccine 2008, 26, 4758–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, S.; Giagulli, C.; Caccuri, F.; Magiera, A.K.; Caruso, A. HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17: A Candidate Antigen for Therapeutic Vaccines against AIDS. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 128, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaria, M.L.; Fiorentini, S.; Focà, E.; Zicari, S.; Giagulli, C.; Caccuri, F.; Francisci, D.; Di Perri, G.; Castelli, F.; Baldelli, F.; et al. Synthetic HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17-Based AT20-KLH Therapeutic Immunization in HIV-1-Infected Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment: A Phase I Safety and Immunogenicity Study. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focà, E.; Iaria, M.L.; Caccuri, F.; Fiorentini, S.; Motta, D.; Giagulli, C.; Castelli, F.; Caruso, A. Long-Lasting Humoral Immune Response Induced in HIV-1-Infected Patients by a Synthetic Peptide (AT20) Derived from the HIV-1 Matrix Protein P17 Functional Epitope. HIV Clin. Trials 2015, 16, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, B.; Paul, S.; Terrat, C.; Bastide, L.; Ensinas, A.; Phelip, C.; Chanut, B.; Bulens-Grassigny, L.; Jospin, F.; Guillon, C. Exploiting Natural Cross-Reactivity between Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 P17 Protein and Anti-Gp41 2F5 Antibody to Induce HIV-1 Neutralizing Responses In Vivo. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathological Biological Activity | p17 (Canonical) | S75X Variant | C-terminal Insertions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Immune Activation | Triggers pro-inflammatory cytokines via p17R/MAPK/ERK in monocytes [24,26] | Enhances B-cell proliferation and IL-6 production in EBV-infected B cells via PI3K/Akt [23,25,40] | Promotes B-cell activation in germinal centers [38,39] |

| Vascular Dysfunction | Induces endothelial activation, EGFR/ERK/FAK signaling, and abnormal remodeling via CXCR-1/2 in brain and lymphatic ECs [11,29,33] | More potent angiogenesis in ECs and Matrigel models [30,33] | Potential PAR-1 binding on ECs speculated to prothrombotic states |

| Lymphangiogenesis | Promotes lymphatic vessel formation via CXCR1/2-Akt/ERK and endothelin-1/ETBR axis in LN-LECs [11] | Stronger in vivo lymphangiogenesis than p17; adipogenic invasion linked to vascular support [30] | Contributes to pro-lymphangiogenic tumor microenvironment in NHL [38] |

| Pro-thrombotic States | Promotes vWF accumulation and secretion in HUVECs/HLMVECs via secretory autophagy [34] | Not specifically reported | Not specifically reported; possible via PAR-1 on ECs |

| Tumorigenesis | Antiproliferative on B cells via PTEN activation/PI3K/Akt inhibition; supports tumor microenvironment by increased angiogenesis/lymphangiogenesis [23] | Strong B-cell clonogenicity via PI3K/Akt activation, PTEN inactivation; lymphoma promotion [23,38] | Confers B-cell growth via PAR-1-EGFR-PI3K/Akt; prevalent in NHL [38] |

| Systemic Inflammation | Sustains IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ production; contributes to HIV-associated IL-6, CRP, D-dimer elevation and inflammaging [24,41] | Amplifies IL-6 and broader cascades in B cells [40] | Indirect, via chronic B-cell dysregulation [38] |

| Neuroinflammatory Processes | Crosses BBB via CXCR2; induces MCP-1, amyloidogenic aggregates, EGFR in neurons and microvessels; cognitive deficits [33,45,46] | More potent angiogenesis in ECs and Matrigel models [30,33]. Potential link to vascular dementia | Not specifically reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastorello, Y.; Arnaut, N.; Straistă, M.; Caccuri, F.; Caruso, A.; Slevin, M. Beyond Viral Assembly: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 p17 in Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411949

Pastorello Y, Arnaut N, Straistă M, Caccuri F, Caruso A, Slevin M. Beyond Viral Assembly: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 p17 in Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411949

Chicago/Turabian StylePastorello, Ylenia, Nicoleta Arnaut, Mihaela Straistă, Francesca Caccuri, Arnaldo Caruso, and Mark Slevin. 2025. "Beyond Viral Assembly: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 p17 in Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411949

APA StylePastorello, Y., Arnaut, N., Straistă, M., Caccuri, F., Caruso, A., & Slevin, M. (2025). Beyond Viral Assembly: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 p17 in Vascular Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411949