Orchestrating HFpEF: How Noncoding RNAs Drive Pathophysiology and Phenotypic Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

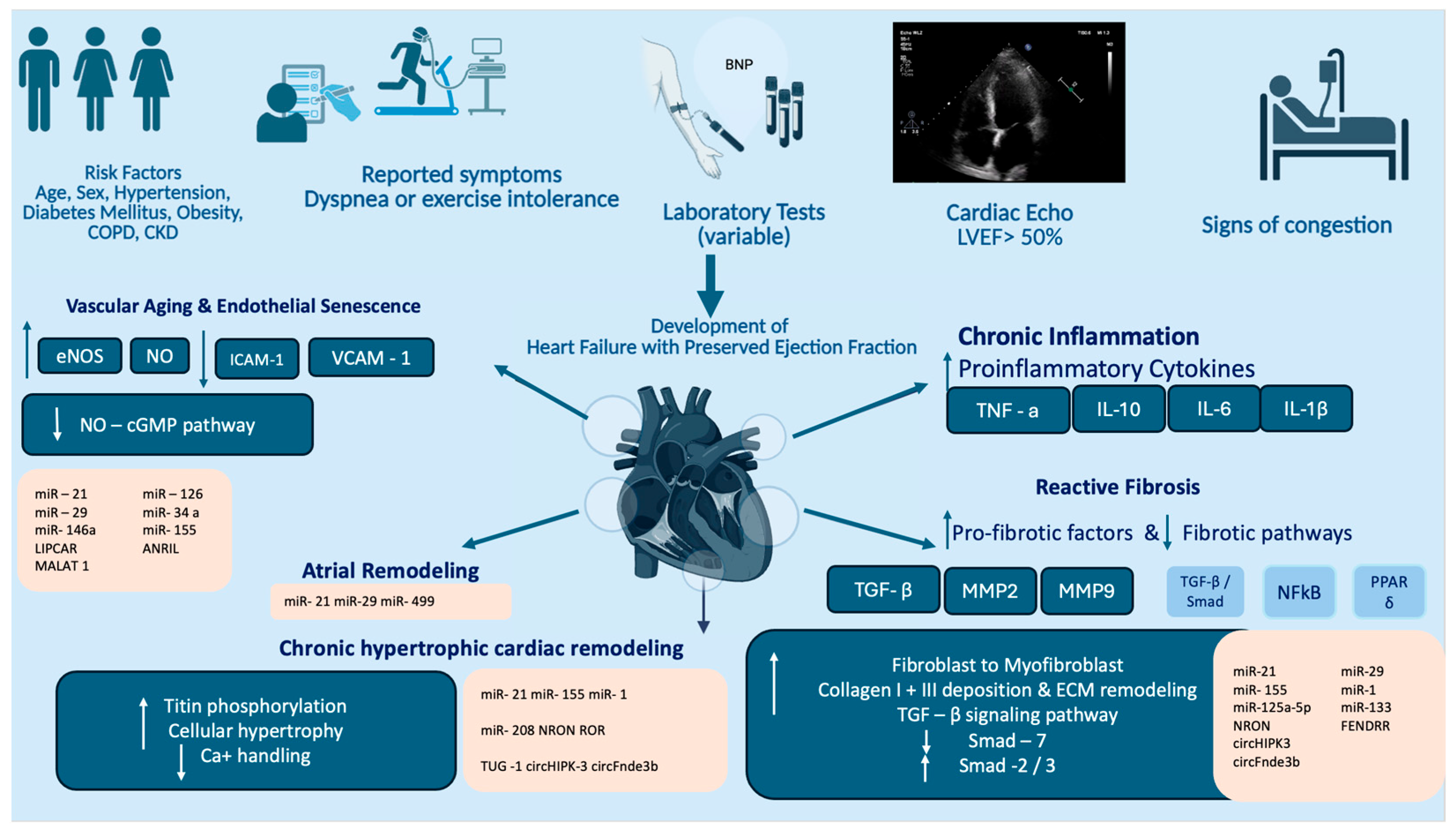

2. Current Pathophysiological Concepts on HFpEF

2.1. Cardiac and Extracardiac Contributors in HFpEF

2.2. Molecular and Cellular Pathways Underlying HFpEF Development

3. Noncoding RNAs as Regulators in Cardiovascular Disease and HFpEF

| Type of Noncoding RNA | Name | Pathophysiological Mechanism | Expression in HFpEF—Disease State | Molecular Pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | miR-21 | Myocardial fibrosis Cardiac hypertrophy Atrial collagen deposition | upregulated | suppression programmed cell death AP-1 and TGF-β1 signaling MAP Kinase pathway | [83,84,85] |

| miR-29 | Myocardial fibrosis ECM remodeling | downregulated | PGC1α pathway | [86,87] | |

| miR-155 | Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis | upregulated in hypertensive individuals | Increased expression associated with greater reductions in SBP following eplerenone treatment | [88,89] | |

| miR-125a-5p | Cardiac fibrosis | antifibrotic role | ETS-1/PDGF-BB signaling pathway | [90] | |

| miRNA-1 | Cardiac hypertrophy Cardiac Fibrosis | downregulated | Inhibition of RasGAP Cdk9 fibronectin Rheb | [91,92,93] | |

| miRNA-133 | Myoblast proliferation Cardiac fibrosis | downregulated | Akt signaling pathway β-adrenergic signaling pathways | [94,95,96,97] | |

| miR-208 | Cardiac Hypertrophy | promotes cardiac hypertrophy in response to high pressure stress | TGF-β signaling | [98,99,100] | |

| miR-499 | Cardiac Remodeling Cardiac contractility | variable | Akt and MAPK signaling pathways | [101,102,103] | |

| Long ncRNAs | NRON | Cardiac hypertrophy Cardiac fibrosis | variable | Calcineurin/NFAT pathway | [104] |

| ROR | Cardiac Hypertrophy | variable | Sponging to miR-133 Suppression of fibrotic gene | [105] | |

| FENDRR | Cardiac fibrosis | upregulated | Upregulated in fibrotic remodeling Depression SMAD3 signaling/miR-106b increased synthesis CTGF, and ACTA2 | [106,107] | |

| CARMEN | Cardiac Differentiation | upregulated | Increased activation of fibrotic and hypertrophic gene networks | [6,108] | |

| TUG-1 | Myocardial fibrosis Cardiac hypertrophy | upregulated | miRNA sponge to miR-29b-3p, miR-29c, miR-133b, miR-129-5p Depression tissue growth factor (CTGF), ATG7, and SMAD3 Activation CHI3L1 | [109,110,111,112] | |

| circular RNAs | circHIPK3 circFndc3b | Cardiac Hypertrophy and Cardiac fibrosis | - | Calcium handling and pro-fibrotic signaling. | [113,114,115] |

| circIGF1R | Cardiac Fibrosis | - |

3.1. The Role of miRNAs in HFpEF Pathogenesis

3.2. Other Noncoding RNAs in HFpEF

3.3. Age- and Sex-Dependent ncRNA Regulation in HFpEF

4. Diagnostic Biomarkers in HFpEF: Focus on miRNAs and Other Noncoding RNAs

| Type of Noncoding RNA | Clinical Use | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-424-5p miR-206 miR-328-5p miR-30c-5p miR-221-3p miR-375-3p miR-19b-3p | Distinguish between individuals with HFpEF and HFrEF | [160] |

| miR-19-b | Distinguish between individuals with HFpEF and HFrEF | [161] | |

| miR-21 | Prognosis of HFpEF among hypertensive individuals | [162,163,164] | |

| miR-423-5p | Multi-microRNA panels to distinguish HFpEF from healthy controls | [178,179] | |

| Long noncoding RNAs | MHRT | Marker of functional capacity in HFpEF patients Prognostic potential | [6] |

| NRON | Prognostic biomarker in heart failure | [165] | |

| LIPCAR | Associated with adverse cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF Predict risk of cardiovascular hospitalization and mortality | [167,168] | |

5. Noncoding RNA-Based Therapies for HFpEF: Potential and Limitations

5.1. Preclinical Data of Noncoding RNAs in Developing HFpEF Therapies

5.2. Advantages and Limitations in Integration of Noncoding RNA Therapies in Clinical Setting

6. Conclusions

7. Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| PKG | Protein kinase G |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 |

| SIRT | Sirtuin |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cell |

| VCAM | Vascular cell adhesion molecule |

| ICAM | Intracellular Adhesion molecule |

| TNF | Tissue Necrosis Factor |

| NFkB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| FENDRR | FOXF1 Adjacent Noncoding Developmental Regulatory RNA |

| LIPCAR | Long intergenic noncoding RNA predicting cardiac remodeling |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

References

- Cannata, A.; McDonagh, T.A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owan, T.E.; Hodge, D.O.; Herges, R.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Roger, V.L.; Redfield, M.M. Trends in Prevalence and Outcome of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Redfield, M.M. Diastolic and Systolic Heart Failure Are Distinct Phenotypes within the Heart Failure Spectrum. Circulation 2011, 123, 2006–2013, discussion 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global Burden of Heart Failure: A Comprehensive and Updated Review of Epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287, Erratum in Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Teng, T.-H.; Tay, W.T.; Hung, C.L.; Narasimhan, C.; Shimizu, W.; Park, S.W.; Liew, H.B.; Ngarmukos, T.; Reyes, E.B.; et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Asia. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontaraki, J.E.; Marketou, M.E.; Kochiadakis, G.E.; Patrianakos, A.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Plevritaki, A.; Papadaki, S.; Alevizaki, A.; Theodosaki, O.; Parthenakis, F.I. Long Noncoding RNAs in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Hypertensive Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Relation to Their Functional Capacity. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2021, 62, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights into Diagnosis and Pathophysiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Pang, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, N.; Yang, L. Cardiac Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 221, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyberg, D.J.; Patel, R.B.; Zhang, M.J. Time’s Imprint on the Left Atrium: Aging and Atrial Myopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Aging 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, C.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Tang, X. The Aging Heart in Focus: The Advanced Understanding of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Rhee, J.; Li, H. The Dark Side of Vascular Aging: Noncoding Ribonucleic Acids in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Cells 2025, 14, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharagozloo, K.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Heckman, G.; Rose, R.A.; Howlett, J.; Howlett, S.E.; Nattel, S. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Elderly Population: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Considerations. Can. J. Cardiol. 2024, 40, 1424–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, H.; Hassoun, R.; Mügge, A.; Kovács, Á.; Hamdani, N. Current Understanding of Molecular Pathophysiology of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 928232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.S.; Sorrell, V.L. Cell- and Molecular-Level Mechanisms Contributing to Diastolic Dysfunction in HFpEF. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikert, A.; Fontana, M.; Solomon, S.D.; Thum, T. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Myocardial Fibrosis in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Mechanisms and Treatment. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.; Rutten, F.H.; Lee, M.M.; Hawkins, N.M.; Petrie, M.C. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Everything the Clinician Needs to Know. Lancet 2024, 403, 1083–1092, Erratum in Lancet 2024, 403, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.N.V.; Obokata, M.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Lin, G.; Borlaug, B.A. Atrial Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. The Adipokine Hypothesis of Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Novel Framework to Explain Pathogenesis and Guide Treatment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 1269–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Zile, M.R. From Systemic Inflammation to Myocardial Fibrosis: The Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Paradigm Revisited. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1451–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Rodolico, D.; Hill, J.A. Metabolic Inflammation in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Parrott, C.F.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Brubaker, P.H.; Ye, F.; Upadhya, B. Skeletal Muscle Abnormalities in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzman, D.W.; Nicklas, B.; Kraus, W.E.; Lyles, M.F.; Eggebeen, J.; Morgan, T.M.; Haykowsky, M. Skeletal Muscle Abnormalities and Exercise Intolerance in Older Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 306, H1364–H1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandalis, L.; Kitzman, D.W.; Nicklas, B.J.; Lyles, M.; Brubaker, P.; Nelson, M.B.; Gordon, M.; Stone, J.; Bergstrom, J.; Neufer, P.D.; et al. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Respiration and Exercise Intolerance in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamo, C.E.; DeJong, C.; Hartshorne-Evans, N.; Lund, L.H.; Shah, S.J.; Solomon, S.; Lam, C.S.P. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatner, S.F.; Zhang, J.; Vyzas, C.; Mishra, K.; Graham, R.M.; Vatner, D.E. Vascular Stiffness in Aging and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 762437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, J.C.; Lampi, M.C.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Age-Related Vascular Stiffening: Causes and Consequences. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Navarro, I.; Botana, L.; Diez-Mata, J.; Tesoro, L.; Jimenez-Guirado, B.; Gonzalez-Cucharero, C.; Alcharani, N.; Zamorano, J.L.; Saura, M.; Zaragoza, C. Replicative Endothelial Cell Senescence May Lead to Endothelial Dysfunction by Increasing the BH2/BH4 Ratio Induced by Oxidative Stress, Reducing BH4 Availability, and Decreasing the Expression of eNOS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bink, D.I.; Pauli, J.; Maegdefessel, L.; Boon, R.A. Endothelial microRNAs and Long Noncoding RNAs in Cardiovascular Ageing. Atherosclerosis 2023, 374, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucci, A.; Macrì, F.; Castiglione, S.; Badi, I.; Vinci, M.C.; Zuccolo, E. MicroRNA-34a: The Bad Guy in Age-Related Vascular Diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 7355–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantler, P.D.; Lakatta, E.G. Arterial-Ventricular Coupling with Aging and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Chan, W.X.; Charles, C.J.; Richards, A.M.; Lee, L.C.; Leo, H.L.; Yap, C.H. Morphological, Functional, and Biomechanical Progression of LV Remodelling in a Porcine Model of HFpEF. J. Biomech. 2022, 144, 111348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.R.; Marletta, M.A. Structure and Regulation of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhao, M.; Zu, L. The NO-cGMP-PKG Axis in HFpEF: From Pathological Mechanisms to Potential Therapies. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Comorbidities Drive Myocardial Dysfunction and Remodeling through Coronary Microvascular Endothelial Inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teuber, J.P.; Essandoh, K.; Hummel, S.L.; Madamanchi, N.R.; Brody, M.J. NADPH Oxidases in Diastolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momot, K.; Krauz, K.; Czarzasta, K.; Zarębiński, M.; Puchalska, L.; Wojciechowska, M. Evaluation of Nitrosative/Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soucy, K.G.; Ryoo, S.; Benjo, A.; Lim, H.K.; Gupta, G.; Sohi, J.S.; Elser, J.; Aon, M.A.; Nyhan, D.; Shoukas, A.A.; et al. Impaired Shear Stress-Induced Nitric Oxide Production through Decreased NOS Phosphorylation Contributes to Age-Related Vascular Stiffness. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, R.S.; Preedy, M.E.J.; Dukinfield, M.S.; Chu, S.M.; Aubdool, A.A.; Bubb, K.J.; Moyes, A.J.; Tones, M.A.; Hobbs, A.J. Phosphodiesterase 2 Inhibition Preferentially Promotes NO/Guanylyl Cyclase/cGMP Signaling to Reverse the Development of Heart Failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7428–E7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshiri, K.; Ataei Ataabadi, E.; Portilla Fernandez, E.C.; Jan Danser, A.H.; Roks, A.J.M. The Importance of the Nitric Oxide-cGMP Pathway in Age-Related Cardiovascular Disease: Focus on Phosphodiesterase-1 and Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 127, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Chuang, C.-C.; Hemmelgarn, B.T.; Best, T.M. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Defining the Function of ROS and NO. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, S.; Farmakis, I.T.; Milioglou, I.; Doundoulakis, I.; Gorodeski, E.Z.; Konstantinides, S.V.; Cooper, L.; Zanos, S.; Stavrakis, S.; Giamouzis, G.; et al. Pharmacological Treatments in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced and Preserved Ejection Fraction: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Butler, J.; Kosiborod, M.N. Chapter 3: Clinical Trials of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors for Treatment of Heart Failure. Am. J. Med. 2024, 137, S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micu, M.A.; Cozac, D.A.; Scridon, A. miRNA-Orchestrated Fibroinflammatory Responses in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Translational Opportunities for Precision Medicine. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.F.; Malik, A.; Brozovich, F.V. Aging and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Compr. Physiol. 2022, 12, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.B.; Colangelo, L.A.; Reiner, A.P.; Gross, M.D.; Jacobs, D.R.; Launer, L.J.; Lima, J.A.C.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Shah, S.J. Cellular Adhesion Molecules in Young Adulthood and Cardiac Function in Later Life. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2156–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Lecarpentier, Y. TGF-β in Fibrosis by Acting as a Conductor for Contractile Properties of Myofibroblasts. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelullo, M.; Zema, S.; Nardozza, F.; Checquolo, S.; Screpanti, I.; Bellavia, D. Wnt, Notch, and TGF-β Pathways Impinge on Hedgehog Signaling Complexity: An Open Window on Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigert, C.; Brodbeck, K.; Klopfer, K.; Häring, H.U.; Schleicher, E.D. Angiotensin II Induces Human TGF-Beta 1 Promoter Activation: Similarity to Hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 2002, 45, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Regulation of the Inflammatory Response in Cardiac Repair. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, A.; Humeres, C.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The Role of Smad Signaling Cascades in Cardiac Fibrosis. Cell. Signal. 2021, 77, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, I.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Diabetes-Associated Cardiac Fibrosis: Cellular Effectors, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 90, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-K.; Lee, J.-K.; Hsu, J.-C.; Su, M.-Y.M.; Wu, Y.-F.; Lin, T.-T.; Lan, C.-W.; Hwang, J.-J.; Lin, L.-Y. Myocardial Adipose Deposition and the Development of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantsila, E.; Shantsila, A.; Blann, A.D.; Lip, G.Y.H. Left Ventricular Fibrosis in Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidis, I.; Lekakis, J.P.; Nikolaou, M.; Paraskevaidis, I.; Andreadou, I.; Kaplanoglou, T.; Katsimbri, P.; Skarantavos, G.; Soucacos, P.N.; Kremastinos, D.T. Inhibition of Interleukin-1 by Anakinra Improves Vascular and Left Ventricular Function in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Circulation 2008, 117, 2662–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, K.; Sun, Z. Aging Impairs Arterial Compliance via Klotho-Mediated Downregulation of B-Cell Population and IgG Levels. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Niu, K.; Lian, P.; Hu, Y.; Shuai, Z.; Gao, S.; Ge, S.; Xu, T.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, Z. Pathological Bases and Clinical Application of Long Noncoding RNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases. Hypertension 2021, 78, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darden, C.M.; Vasu, S.; Mattke, J.; Liu, Y.; Rhodes, C.J.; Naziruddin, B.; Lawrence, M.C. Calcineurin/NFATc2 and PI3K/AKT Signaling Maintains β-Cell Identity and Function during Metabolic and Inflammatory Stress. iScience 2022, 25, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ding, F.; Xiang, Y.K.; Hao, L.; Zhao, M. Noncoding RNAs in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. Cells 2022, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovich, S.J.; Wang, W.; Tu, Y.; Eschenbacher, W.H.; Dorn, L.E.; Condorelli, G.; Diwan, A.; Nerbonne, J.M.; Dorn, G.W. MicroRNA-133a Protects Against Myocardial Fibrosis and Modulates Electrical Repolarization Without Affecting Hypertrophy in Pressure-Overloaded Adult Hearts. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.-L.; Chen, C.; Huo, R.; Wang, N.; Li, Z.; Tu, Y.-J.; Hu, J.-T.; Chu, X.; Huang, W.; Yang, B.-F. Reciprocal Repression between microRNA-133 and Calcineurin Regulates Cardiac Hypertrophy: A Novel Mechanism for Progressive Cardiac Hypertrophy. Hypertension 2010, 55, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Chong, L.; Lin, P.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Q.; Li, C. MicroRNA-133a Alleviates Airway Remodeling in Asthtama Through PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway by Targeting IGF1R. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 4068–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callis, T.E.; Pandya, K.; Seok, H.Y.; Tang, R.-H.; Tatsuguchi, M.; Huang, Z.-P.; Chen, J.-F.; Deng, Z.; Gunn, B.; Shumate, J.; et al. MicroRNA-208a Is a Regulator of Cardiac Hypertrophy and Conduction in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 2772–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.L.; Hullinger, T.G.; Semus, H.M.; Dickinson, B.A.; Seto, A.G.; Lynch, J.M.; Stack, C.; Latimer, P.A.; Olson, E.N.; van Rooij, E. Therapeutic Inhibition of miR-208a Improves Cardiac Function and Survival during Heart Failure. Circulation 2011, 124, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2008, 214, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beermann, J.; Piccoli, M.-T.; Viereck, J.; Thum, T. Non-Coding RNAs in Development and Disease: Background, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Approaches. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1297–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.L.; Sheppard, D.; Duffield, J.S.; Violette, S. Therapy for Fibrotic Diseases: Nearing the Starting Line. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 167sr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boichenko, V.; Noakes, V.M.; Reilly-O’Donnell, B.; Luciani, G.B.; Emanueli, C.; Martelli, F.; Gorelik, J. Circulating Non-Coding RNAs as Indicators of Fibrosis and Heart Failure Severity. Cells 2025, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, R.; Bugg, D.; Olszewski, E.; Davis, J. Regulators of Cardiac Fibroblast Cell State. Matrix Biol. 2020, 91–92, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, D.; Wang, J. Noncoding RNAs: Master Regulator of Fibroblast to Myofibroblast Transition in Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Chi, J.-T.; Dudoit, S.; Bondre, C.; van de Rijn, M.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Diversity, Topographic Differentiation, and Positional Memory in Human Fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12877–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Vitorino, T.; Ferraz do Prado, A.; Bruno de Assis Cau, S.; Rizzi, E. MMP-2 and Its Implications on Cardiac Function and Structure: Interplay with Inflammation in Hypertension. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 215, 115684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, Y.L.L.; do Carmo Neto, J.R.; Franco, P.I.R.; Helmo, F.R.; Dos Reis, M.A.; de Oliveira, F.A.; Celes, M.R.N.; da Silva, M.V.; Machado, J.R. The Influence of IL-11 on Cardiac Fibrosis in Experimental Models: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, H.; Ge, D.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ge, T.; et al. Mir-21 Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis After Myocardial Infarction Via Targeting Smad7. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgaard, L.T.; Sørensen, A.E.; Hardikar, A.A.; Joglekar, M.V. The microRNA-29 Family: Role in Metabolism and Metabolic Disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 323, C367–C377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Prattichizzo, F.; Giuliani, A.; Matacchione, G.; Rippo, M.R.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Bonafè, M. miR-21 and miR-146a: The microRNAs of Inflammaging and Age-Related Diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Qiu, B.; Li, H.; Shi, R. Shenge powder inhibits myocardial fibrosis in rats with post-myocardial infarction heart failure through LOXL2/TGF-β1/IL-11 signaling pathway. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2025, 54, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Duan, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. TGF-Β1/IL-11 Positive Loop between Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell and Fibroblast Promotes the Ectopic Calcification of Renal Interstitial Fibroblasts in Rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 240, 117074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartekova, M.; Radosinska, J.; Jelemensky, M.; Dhalla, N.S. Role of Cytokines and Inflammation in Heart Function During Health and Disease. Heart Fail. Rev. 2018, 23, 733–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarswamy, R.; Volkmann, I.; Jazbutyte, V.; Dangwal, S.; Park, D.-H.; Thum, T. Transforming Growth Factor-β-Induced Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is Partly Mediated by microRNA-21. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Komers, R.; Carew, R.; Winbanks, C.E.; Xu, B.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Koh, P.; Thomas, M.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Gregorevic, P.; et al. Suppression of microRNA-29 Expression by TGF-Β1 Promotes Collagen Expression and Renal Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, D.C.; Bell, P.D.; Hill, J.A. Fibrosis—A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.L.; Armugam, A.; Sepramaniam, S.; Karolina, D.S.; Lim, K.Y.; Lim, J.Y.; Chong, J.P.C.; Ng, J.Y.X.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chan, M.M.Y.; et al. Circulating microRNAs in Heart Failure with Reduced and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, C.; Batkai, S.; Dangwal, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Foinquinos, A.; Holzmann, A.; Just, A.; Remke, J.; Zimmer, K.; Zeug, A.; et al. Cardiac Fibroblast-Derived microRNA Passenger Strand-Enriched Exosomes Mediate Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thum, T.; Gross, C.; Fiedler, J.; Fischer, T.; Kissler, S.; Bussen, M.; Galuppo, P.; Just, S.; Rottbauer, W.; Frantz, S.; et al. MicroRNA-21 Contributes to Myocardial Disease by Stimulating MAP Kinase Signalling in Fibroblasts. Nature 2008, 456, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, O.; Löhfelm, B.; Thum, T.; Gupta, S.K.; Puhl, S.-L.; Schäfers, H.-J.; Böhm, M.; Laufs, U. Role of miR-21 in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrosis. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2012, 107, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravia, X.M.; Fanjul, V.; Oliver, E.; Roiz-Valle, D.; Morán-Álvarez, A.; Desdín-Micó, G.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Cabo, R.; Vega, J.A.; Rodríguez, F.; et al. The microRNA-29/PGC1α Regulatory Axis Is Critical for Metabolic Control of Cardiac Function. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; McLendon, J.M.; Peck, B.D.; Chen, B.; Song, L.-S.; Boudreau, R.L. Modulation of miR-29 Influences Myocardial Compliance Likely through Coordinated Regulation of Calcium Handling and Extracellular Matrix. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 34, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, R.S.; Rajagopalan, S.; Natarajan, R.; Deiuliis, J.A. Noncoding RNAs in Cardiovascular Disease: Pathological Relevance and Emerging Role as Biomarkers and Therapeutics. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, J.J.; McCurley, A.; Davel, A.P.; McCarthy, J.; Bender, S.B.; Hong, K.; Yang, Y.; Yoo, J.-K.; Aronovitz, M.; Baur, W.E.; et al. Vascular Mineralocorticoid Receptor Regulates microRNA-155 to Promote Vasoconstriction and Rising Blood Pressure with Aging. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e88942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethupathy, P.; Borel, C.; Gagnebin, M.; Grant, G.R.; Deutsch, S.; Elton, T.S.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G.; Antonarakis, S.E. Human microRNA-155 on Chromosome 21 Differentially Interacts with Its Polymorphic Target in the AGTR1 3′ Untranslated Region: A Mechanism for Functional Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Related to Phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Chen, Y.; He, R.; Shi, Y.; Su, L. Rescuing Infusion of miRNA-1 Prevents Cardiac Remodeling in a Heart-Selective miRNA Deficient Mouse. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 607–613, Erratum in Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 498, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.K.; Toyama, Y.; Chiang, H.R.; Gupta, S.; Bauer, M.; Medvid, R.; Reinhardt, F.; Liao, R.; Krieger, M.; Jaenisch, R.; et al. Loss of Cardiac microRNA-Mediated Regulation Leads to Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, D.; Hong, C.; Chen, I.-Y.; Lypowy, J.; Abdellatif, M. MicroRNAs Play an Essential Role in the Development of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.-Q.; Jiang, Z.-M.; Zhao, Q.-P.; Xin, F. MicroRNA-133a Improves the Cardiac Function and Fibrosis Through Inhibiting Akt in Heart Failure Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 71, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carè, A.; Catalucci, D.; Felicetti, F.; Bonci, D.; Addario, A.; Gallo, P.; Bang, M.-L.; Segnalini, P.; Gu, Y.; Dalton, N.D.; et al. MicroRNA-133 Controls Cardiac Hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Williams, A.H.; Qi, X.; Richardson, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. microRNA-133a Regulates Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Suppresses Smooth Muscle Gene Expression in the Heart. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 3242–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, A.; Zaglia, T.; Di Mauro, V.; Carullo, P.; Viggiani, G.; Borile, G.; Di Stefano, B.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Gualazzi, M.G.; Elia, L.; et al. MicroRNA-133 Modulates the Β1-Adrenergic Receptor Transduction Cascade. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X. The Functions of microRNA-208 in the Heart. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 160, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E.; Sutherland, L.B.; Qi, X.; Richardson, J.A.; Hill, J.; Olson, E.N. Control of Stress-Dependent Cardiac Growth and Gene Expression by a microRNA. Science 2007, 316, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, J.T.C.; Huang, Y.; Gilmore, J.; Srivastava, D. Elevated miR-499 Levels Blunt the Cardiac Stress Response. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-X.; Jiao, J.-Q.; Li, Q.; Long, B.; Wang, K.; Liu, J.-P.; Li, Y.-R.; Li, P.-F. miR-499 Regulates Mitochondrial Dynamics by Targeting Calcineurin and Dynamin-Related Protein-1. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, G.W.; Matkovich, S.J.; Eschenbacher, W.H.; Zhang, Y. A Human 3′ miR-499 Mutation Alters Cardiac mRNA Targeting and Function. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovich, S.J.; Hu, Y.; Eschenbacher, W.H.; Dorn, L.E.; Dorn, G.W. Direct and Indirect Involvement of microRNA-499 in Clinical and Experimental Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepfner, J.; Leonardy, J.; Lu, D.; Schmidt, K.; Hunkler, H.J.; Biß, S.; Foinquinos, A.; Xiao, K.; Regalla, K.; Ramanujam, D.; et al. The Long Non-Coding RNA NRON Promotes the Development of Cardiac Hypertrophy in the Murine Heart. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J. Long Non-Coding RNA-ROR Mediates the Reprogramming in Cardiac Hypertrophy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranski, P.; Stankiewicz, P. Long Non-Coding RNA FENDRR: Gene Structure, Expression, and Biological Relevance. Genes 2021, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Liao, C.; Li, H.; Yu, G. LncRNA SOX2OT/Smad3 Feedback Loop Promotes Myocardial Fibrosis in Heart Failure. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2469–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounzain, S.; Micheletti, R.; Arnan, C.; Plaisance, I.; Cecchi, D.; Schroen, B.; Reverter, F.; Alexanian, M.; Gonzales, C.; Ng, S.Y.; et al. CARMEN, a Human Super Enhancer-Associated Long Noncoding RNA Controlling Cardiac Specification, Differentiation and Homeostasis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 89, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. Taurine Up-Regulated 1: A Dual Regulator in Immune Cell-Mediated Pathogenesis of Human Diseases. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2025, 197, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Jian, Z.; Xiao, Y. Long Noncoding RNA TUG1 Promotes Cardiac Fibroblast Transformation to Myofibroblasts via miR-29c in Chronic Hypoxia. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, N.; Ma, Q.; Fan, F.; Ma, X. LncRNA TUG1 Acts as a Competing Endogenous RNA to Mediate CTGF Expression by Sponging miR-133b in Myocardial Fibrosis after Myocardial Infarction. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shan, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, D. CHI3L1 Promotes Myocardial Fibrosis via Regulating lncRNA TUG1/miR-495-3p/ETS1 Axis. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 1436–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsanathan, R.; Sunil, S.; Byju, R. Circular RNAs in Cardiovascular Disease: A Paradigm Shift in Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Life Sci. 2025, 379, 123877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Bartekova, M.; Gandhi, S.; Greco, S.; Madè, A.; Sarkar, M.; Stopa, V.; Tastsoglou, S.; de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; Devaux, Y.; et al. Circular RNA Regulatory Role in Pathological Cardiac Remodelling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Schmidt, K.; Groß, S.; Lu, D.; Xiao, K.; Neufeldt, D.; Cushman, S.; Lehmann, N.; Thum, S.; Pfanne, A.; et al. Circular RNA circIGF1R Controls Cardiac Fibroblast Proliferation through Regulation of Carbohydrate Metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarswamy, R.; Thum, T. Non-Coding RNAs in Cardiac Remodeling and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, S.; Guasch, E.; Luo, X.; Naud, P.; Le Quang, K.; Shi, Y.; Tardif, J.-C.; Comtois, P.; Nattel, S. Role for MicroRNA-21 in Atrial Profibrillatory Fibrotic Remodeling Associated with Experimental Postinfarction Heart Failure. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-T.; Shih, J.-Y.; Lin, Y.-W.; Huang, T.-L.; Chen, Z.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Chu, J.-S.; Liu, P.Y. miR-21 Upregulation Exacerbates Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Aged Hearts. Aging 2022, 14, 5925–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Zhao, X.-D.; Shi, K.-H.; Ding, X.-S.; Tao, H. MiR-21-3p Triggers Cardiac Fibroblasts Pyroptosis in Diabetic Cardiac Fibrosis via Inhibiting Androgen Receptor. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 399, 112464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, F.; Furini, G.; Casieri, V.; Mariani, M.; Bianchi, G.; Storti, S.; Chiappino, D.; Maffei, S.; Solinas, M.; Aquaro, G.D.; et al. Late Plasma Exosome microRNA-21-5p Depicts Magnitude of Reverse Ventricular Remodeling after Early Surgical Repair of Primary Mitral Valve Regurgitation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 943068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, M.; Farquharson, C.; Stephen, L.A. The Role of miR-29 Family in Disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 122, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E.; Sutherland, L.B.; Thatcher, J.E.; DiMaio, J.M.; Naseem, R.H.; Marshall, W.S.; Hill, J.A.; Olson, E.N. Dysregulation of microRNAs after Myocardial Infarction Reveals a Role of miR-29 in Cardiac Fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13027–13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, N.; Rao, P.; Wang, L.; Lu, D.; Sun, L. Role of the microRNA-29 Family in Myocardial Fibrosis. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 77, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derda, A.A.; Thum, S.; Lorenzen, J.M.; Bavendiek, U.; Heineke, J.; Keyser, B.; Stuhrmann, M.; Givens, R.C.; Kennel, P.J.; Schulze, P.C.; et al. Blood-Based microRNA Signatures Differentiate Various Forms of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 196, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yin, Z.; Dai, F.-F.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M.-J.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhang, S.-F.; Fu, Z.-F.; Mei, Y.-W.; Zang, M.-X.; et al. miR-29a Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy through Inhibition of PPARδ Expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 13252–13262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-T.; Xu, M.-G. Potential Link between microRNA-208 and Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Xiangya Med. 2021, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupfeld, J.; Ernst, M.; Knyrim, M.; Binas, S.; Kloeckner, U.; Rabe, S.; Quarch, K.; Misiak, D.; Fuszard, M.; Grossmann, C.; et al. miR-208b Reduces the Expression of Kcnj5 in a Cardiomyocyte Cell Line. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, D.C.; Nevis, K.R.; Cashman, T.J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Washko, D.; Guner-Ataman, B.; Burns, C.G.; Burns, C.E. The miR-143-Adducin3 Pathway Is Essential for Cardiac Chamber Morphogenesis. Development 2010, 137, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, S.U.; Scherz, P.J.; Cordes, K.R.; Ivey, K.N.; Stainier, D.Y.R.; Srivastava, D. microRNA-138 Modulates Cardiac Patterning during Embryonic Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17830–17835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrello, E.R.; Johnson, B.A.; Aurora, A.B.; Simpson, E.; Nam, Y.-J.; Matkovich, S.J.; Dorn, G.W.; van Rooij, E.; Olson, E.N. MiR-15 Family Regulates Postnatal Mitotic Arrest of Cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Minobe, W.; Bristow, M.R.; Leinwand, L.A. Myosin Heavy Chain Isoform Expression in the Failing and Nonfailing Human Heart. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thum, T.; Galuppo, P.; Wolf, C.; Fiedler, J.; Kneitz, S.; van Laake, L.W.; Doevendans, P.A.; Mummery, C.L.; Borlak, J.; Haverich, A.; et al. MicroRNAs in the Human Heart: A Clue to Fetal Gene Reprogramming in Heart Failure. Circulation 2007, 116, 258–267, Erratum in Circulation 2007, 116, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Yalcin, A.; Meyer, J.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl, T. Identification of Tissue-Specific microRNAs from Mouse. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Q. miR-133: A Suppressor of Cardiac Remodeling? Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Narumi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Otaki, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Aono, T.; Goto, J.; Toshima, T.; Sugai, T.; Wanezaki, M.; et al. The Association between microRNA-21 and Hypertension-Induced Cardiac Remodeling. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Friggeri, A.; Yang, Y.; Milosevic, J.; Ding, Q.; Thannickal, V.J.; Kaminski, N.; Abraham, E. miR-21 Mediates Fibrogenic Activation of Pulmonary Fibroblasts and Lung Fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zhu, L.; Yang, T. Fendrr Involves in the Pathogenesis of Cardiac Fibrosis via Regulating miR-106b/SMAD3 Axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketou, M.; Kontaraki, J.; Kochiadakis, G.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Vernardos, M.; Fragkiadakis, K.; Lempidakis, D.; Theodosaki, O.; Logakis, J.; Parthenakis, F. Long Non Coding Rnas in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in Hypertensives with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Their Relation to Their Functional Capacity. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygitowicz, G.; Sitkiewicz, D. Involvement of circRNAs in the Development of Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Gao, X.-M.; Winbanks, C.E.; Boey, E.J.H.; Tham, Y.K.; Kiriazis, H.; Gregorevic, P.; Obad, S.; Kauppinen, S.; Du, X.-J.; et al. Therapeutic Inhibition of the miR-34 Family Attenuates Pathological Cardiac Remodeling and Improves Heart Function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17615–17620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, F.S.; Pancoast, J.R.; Lee, R.T. Keep PNUTS in Your Heart. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, R.A.; Iekushi, K.; Lechner, S.; Seeger, T.; Fischer, A.; Heydt, S.; Kaluza, D.; Tréguer, K.; Carmona, G.; Bonauer, A.; et al. MicroRNA-34a Regulates Cardiac Ageing and Function. Nature 2013, 495, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazbutyte, V.; Fiedler, J.; Kneitz, S.; Galuppo, P.; Just, A.; Holzmann, A.; Bauersachs, J.; Thum, T. MicroRNA-22 Increases Senescence and Activates Cardiac Fibroblasts in the Aging Heart. Age 2013, 35, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Almen, G.C.; Verhesen, W.; van Leeuwen, R.E.W.; van de Vrie, M.; Eurlings, C.; Schellings, M.W.M.; Swinnen, M.; Cleutjens, J.P.M.; van Zandvoort, M.A.M.J.; Heymans, S.; et al. MicroRNA-18 and microRNA-19 Regulate CTGF and TSP-1 Expression in Age-Related Heart Failure. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florijn, B.W.; Bijkerk, R.; van der Veer, E.P.; van Zonneveld, A.J. Gender and Cardiovascular Disease: Are Sex-Biased microRNA Networks a Driving Force Behind Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Women? Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, R.; Penzkofer, D.; Zühlke, S.; Fischer, A.; Husada, W.; Xu, Q.-F.; Baloch, E.; van Rooij, E.; Zeiher, A.M.; Kupatt, C.; et al. Inhibition of microRNA-92a Protects against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in a Large-Animal Model. Circulation 2013, 128, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Buchan, R.J.; Cook, S.A. MicroRNA-223 Regulates Glut4 Expression and Cardiomyocyte Glucose Metabolism. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 86, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusic, A.; Salgado-Somoza, A.; Paes, A.B.; Stefanizzi, F.M.; Martínez-Alarcón, N.; Pinet, F.; Martelli, F.; Devaux, Y.; Robinson, E.L.; Novella, S.; et al. Approaching Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Non-Coding RNA Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, P.; Alihemmati, A.; Nasirzadeh, M.; Yousefi, H.; Habibi, M.; Ahmadiasl, N. Involvement of microRNA-133 and -29 in Cardiac Disturbances in Diabetic Ovariectomized Rats. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2016, 19, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, J.A.; Collins, F.S. Policy: NIH to Balance Sex in Cell and Animal Studies. Nature 2014, 509, 282–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Nishikimi, T.; Kuwahara, K. Atrial and Brain Natriuretic Peptides: Hormones Secreted from the Heart. Peptides 2019, 111, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C. Essential Biochemistry and Physiology of (NT-pro)BNP. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2004, 6, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.L.; Maisel, A.S.; Anand, I.; Bozkurt, B.; de Boer, R.A.; Felker, G.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greenberg, B.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Kiernan, M.S.; et al. Role of Biomarkers for the Prevention, Assessment, and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e1054–e1091. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000490 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Neuen, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Beldhuis, I.; Myhre, P.; Desai, A.S.; Skali, H.; Mc Causland, F.R.; McGrath, M.; Anand, I.; et al. Natriuretic Peptides, Kidney Function, and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Huang, W.; Fan, J.; Lei, H. Midregional Pro-Atrial Natriuretic Peptide Is a Superior Biomarker to N-Terminal pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in the Diagnosis of Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Medicine 2018, 97, e12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudim, M.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Sun, J.-L.; Anstrom, K.J.; Bart, B.A.; Butler, J.; AbouEzzeddine, O.; Greene, S.J.; Mentz, R.J.; Redfield, M.M.; et al. High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Hospitalized and Ambulatory Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights from the Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e010364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, W.C.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Mebazaa, A.; Bauersachs, J.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Januzzi, J.L.; Maisel, A.S.; McDonald, K.; Mueller, T.; et al. Circulating Heart Failure Biomarkers beyond Natriuretic Peptides: Review from the Biomarker Study Group of the Heart Failure Association (HFA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1610–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, C.; Blankenberg, S. Biomarkers for Heart Failure: Small Molecules with High Clinical Relevance. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvan, R.; Hosseinpour, M.; Moradi, Y.; Devaux, Y.; Cataliotti, A.; da Silva, G.J.J. Diagnostic Performance of microRNAs in the Detection of Heart Failure with Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 2212–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, R.-L.; Liu, S.-X.; Dong, S.-H.; Zhao, X.-X.; Zhang, B.-L. Diagnostic Value of Circulating microRNA-19b in Heart Failure. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marketou, M.; Kontaraki, J.; Zacharis, E.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Fragkiadakis, K.; Kampanieris, E.; Plevritaki, A.; Savva, E.; Malikides, O.; Chlouverakis, G.; et al. Peripheral Blood MicroRNA-21 as a Predictive Biomarker for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Old Hypertensives. Am. J. Hypertens. 2024, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, F.; Liu, H. Correlation Between Serum Levels of microRNA-21 and Inflammatory Factors in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Medicine 2022, 101, e30596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nun, D.; Buja, L.M.; Fuentes, F. Prevention of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF): Reexamining microRNA-21 Inhibition in the Era of Oligonucleotide-Based Therapeutics. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020, 49, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, L.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, Y.; Feng, B.; Cui, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Circulating Long Non-Coding RNAs NRON and MHRT as Novel Predictive Biomarkers of Heart Failure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Masihipour, N.; Milasi, Y.E.; Dehmordi, R.M.; Reiner, Ž.; Asadi, S.; Mohammadi, F.; Khalilzadeh, P.; Rostami, M.; Asemi, Z.; et al. New Insights into the Long Non-Coding RNAs Dependent Modulation of Heart Failure and Cardiac Hypertrophy: From Molecular Function to Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 1404–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meessen, J.M.T.A.; Bär, C.; di Dona, F.M.; Staszewsky, L.I.; Di Giulio, P.; Di Tano, G.; Costa, A.; Leonardy, J.; Novelli, D.; Nicolis, E.B.; et al. LIPCAR Is Increased in Chronic Symptomatic HF Patients. A Sub-Study of the GISSI-HF Trial. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarswamy, R.; Bauters, C.; Volkmann, I.; Maury, F.; Fetisch, J.; Holzmann, A.; Lemesle, G.; de Groote, P.; Pinet, F.; Thum, T. Circulating Long Noncoding RNA, LIPCAR, Predicts Survival in Patients with Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; Kenneweg, F.; Bang, C.; Toro, R.; van der Meer, R.W.; Rijzewijk, L.J.; Smit, J.W.; Lamb, H.J.; Llorente-Cortes, V.; Thum, T. Circulating Long-Non Coding RNAs as Biomarkers of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function and Remodelling in Patients with Well-Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkieh, A.; Beseme, O.; Saura, O.; Charrier, H.; Michel, J.-B.; Amouyel, P.; Thum, T.; Bauters, C.; Pinet, F. LIPCAR Levels in Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Is Associated with Left Ventricle Remodeling Post-Myocardial Infarction. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresci, S.; Pereira, N.L.; Ahmad, F.; Byku, M.; de las Fuentes, L.; Lanfear, D.E.; Reilly, C.M.; Owens, A.T.; Wolf, M.J. Heart Failure in the Era of Precision Medicine: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2019, 12, 458–485. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HCG.0000000000000058 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Chen, X.; Ba, Y.; Ma, L.; Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; et al. Characterization of microRNAs in Serum: A Novel Class of Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Cancer and Other Diseases. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.-K.; Zhu, J.-Q.; Zhang, J.-T.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Qin, Y.-W.; Jing, Q. Circulating microRNA: A Novel Potential Biomarker for Early Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Humans. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK HFpEF Collaborative Group. Rationale and Design of the United Kingdom Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Registry. Heart 2024, 110, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zile, M.R.; Jhund, P.S.; Baicu, C.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Pieske, B.; Voors, A.A.; Prescott, M.F.; Shi, V.; Lefkowitz, M.; McMurray, J.J.V.; et al. Plasma Biomarkers Reflecting Profibrotic Processes in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction: Data from the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e002551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, R.; Batkai, S.; Bähr, A.; Bozoglu, T.; Straub, S.; Borchert, T.; Viereck, J.; Howe, A.; Hornaschewitz, N.; Oberberger, L.; et al. AntimiR-132 Attenuates Myocardial Hypertrophy in an Animal Model of Percutaneous Aortic Constriction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2923–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täubel, J.; Hauke, W.; Rump, S.; Viereck, J.; Batkai, S.; Poetzsch, J.; Rode, L.; Weigt, H.; Genschel, C.; Lorch, U.; et al. Novel Antisense Therapy Targeting microRNA-132 in Patients with Heart Failure: Results of a First-in-Human Phase 1b Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, X. MiR-423-5p Inhibition Alleviates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Caused by Hypoxia/Reoxygenation through Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway via Targeting MYBL2. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 22034–22043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Gupta, S.K.; O’Connell, E.; Thum, S.; Glezeva, N.; Fendrich, J.; Gallagher, J.; Ledwidge, M.; Grote-Levi, L.; McDonald, K.; et al. MicroRNA Signatures Differentiate Preserved from Reduced Ejection Fraction Heart Failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.G.F.; Tendera, M.; Adamus, J.; Freemantle, N.; Polonski, L.; Taylor, J.; PEP-CHF Investigators. The Perindopril in Elderly People with Chronic Heart Failure (PEP-CHF) Study. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 2338–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, B.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; Clausell, N.; Desai, A.S.; Diaz, R.; Fleg, J.L.; et al. Spironolactone for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorescu, R.M.; Lazar, R.-D.; Ruda, A.; Buda, A.P.; Chiorescu, S.; Mocan, M.; Blendea, D. Current Insights and Future Directions in the Treatment of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, N.; Costantino, S.; Mügge, A.; Lebeche, D.; Tschöpe, C.; Thum, T.; Paneni, F. Leveraging Clinical Epigenetics in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Call for Individualized Therapies. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1940–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casieri, V.; Matteucci, M.; Pasanisi, E.M.; Papa, A.; Barile, L.; Fritsche-Danielson, R.; Lionetti, V. Ticagrelor Enhances Release of Anti-Hypoxic Cardiac Progenitor Cell-Derived Exosomes Through Increasing Cell Proliferation In Vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grune, J.; Beyhoff, N.; Smeir, E.; Chudek, R.; Blumrich, A.; Ban, Z.; Brix, S.; Betz, I.R.; Schupp, M.; Foryst-Ludwig, A.; et al. Selective Mineralocorticoid Receptor Cofactor Modulation as Molecular Basis for Finerenone’s Antifibrotic Activity. Hypertension 2018, 71, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papini, G.; Furini, G.; Matteucci, M.; Biemmi, V.; Casieri, V.; Di Lascio, N.; Milano, G.; Chincoli, L.R.; Faita, F.; Barile, L.; et al. Cardiomyocyte-Targeting Exosomes from Sulforaphane-Treated Fibroblasts Affords Cardioprotection in Infarcted Rats. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Ma, C.; Cui, J.; Zheng, Y. Sulforaphane Protects against Cardiovascular Disease via Nrf2 Activation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 407580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B. Effect of Hypoxia-Induced MicroRNA-210 Expression on Cardiovascular Disease and the Underlying Mechanism. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4727283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, V.; Mohammadi, M.; Dariushnejad, H.; Abhari, A.; Chodari, L.; Mohaddes, G. Cardioprotective Effect of Crocin Combined with Voluntary Exercise in Rat: Role of Mir-126 and Mir-210 in Heart Angiogenesis. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017, 109, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L. Genome-Wide Screening for circRNAs in Epicardial Adipose Tissue of Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 4610–4619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gabisonia, K.; Prosdocimo, G.; Aquaro, G.D.; Carlucci, L.; Zentilin, L.; Secco, I.; Ali, H.; Braga, L.; Gorgodze, N.; Bernini, F.; et al. MicroRNA Therapy Stimulates Uncontrolled Cardiac Repair after Myocardial Infarction in Pigs. Nature 2019, 569, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-K.; Kafert-Kasting, S.; Thum, T. Preclinical and Clinical Development of Noncoding RNA Therapeutics for Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibrandi, L.; Lionetti, V. Interspecies Differences in Mitochondria: Implications for Cardiac and Vascular Translational Research. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 159, 107476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.S.; Kale, P.; Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Grogan, M.; Gustafsson, F.; Hung, R.R.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Damy, T.; González-Duarte, A.; et al. Patisiran Treatment in Patients with Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyer, X.; Vion, A.-C.; Tedgui, A.; Boulanger, C.M. Microvesicles as Cell-Cell Messengers in Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkle, M.; El-Daly, S.M.; Fabbri, M.; Calin, G.A. Noncoding RNA Therapeutics—Challenges and Potential Solutions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi, N.; Ishikawa, K.; Hajjar, R.J. Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2015, 30, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alifragki, A.; Katsi, V.; Fragkiadakis, K.; Karagkounis, T.; Kopidakis, N.; Kallergis, E.; Zacharis, E.; Kampanieris, E.; Simantirakis, E.; Tsioufis, K.; et al. Orchestrating HFpEF: How Noncoding RNAs Drive Pathophysiology and Phenotypic Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411937

Alifragki A, Katsi V, Fragkiadakis K, Karagkounis T, Kopidakis N, Kallergis E, Zacharis E, Kampanieris E, Simantirakis E, Tsioufis K, et al. Orchestrating HFpEF: How Noncoding RNAs Drive Pathophysiology and Phenotypic Outcomes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411937

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlifragki, Angeliki, Vasiliki Katsi, Konstantinos Fragkiadakis, Thomas Karagkounis, Nikolaos Kopidakis, Eleutherios Kallergis, Evangelos Zacharis, Emmanouil Kampanieris, Emmanouil Simantirakis, Konstantinos Tsioufis, and et al. 2025. "Orchestrating HFpEF: How Noncoding RNAs Drive Pathophysiology and Phenotypic Outcomes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411937

APA StyleAlifragki, A., Katsi, V., Fragkiadakis, K., Karagkounis, T., Kopidakis, N., Kallergis, E., Zacharis, E., Kampanieris, E., Simantirakis, E., Tsioufis, K., & Marketou, M. (2025). Orchestrating HFpEF: How Noncoding RNAs Drive Pathophysiology and Phenotypic Outcomes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411937