Integrated Role of Arginine Vasotocin in the Control of Spermatogenesis in Zebrafish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

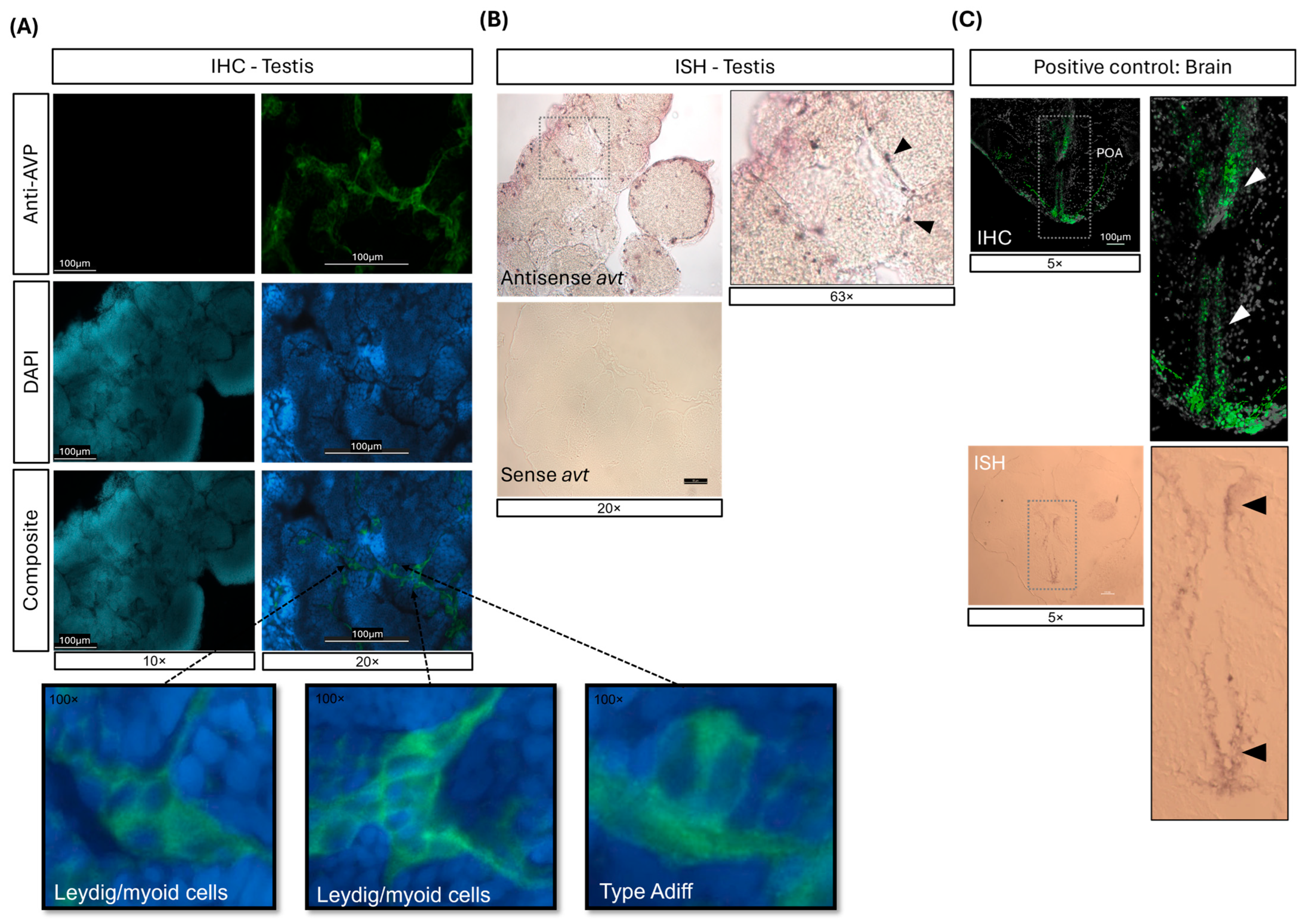

2.1. mRNA and Protein Expression of AVT in the Adult Zebrafish Testis

2.2. AVT Actions on Spermatogonial Dynamics and Late-Stage Germ Cell Proportions

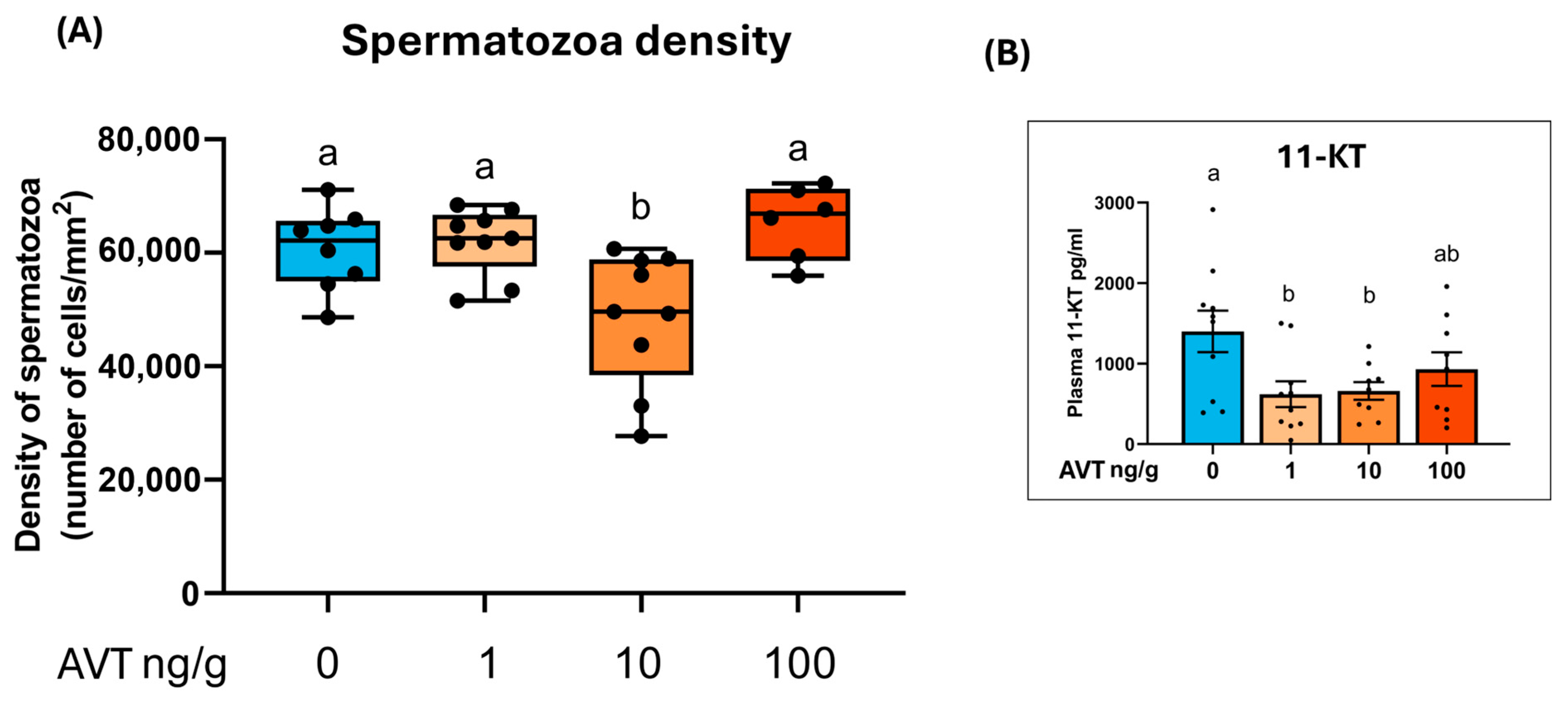

2.3. Spermatozoa Density and Androgen Levels

2.4. Transcript Levels of Gonadotropin Receptors and Apoptotic Signal

2.5. Avt and Avt Receptors Transcripts Are Downregulated in the Testis of Pre-Spawning Fish

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Zebrafish

4.2. Arginine Vasotocin

4.3. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) Injections, In Vivo

4.4. Pre-Spawning Experimental Design

4.5. Histology and Germ Cell Quantification

4.6. Testicular Localization of Avt by In Situ Hybridization (ISH)

4.7. Localization of Testicular Avt-Expressing Cells by Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

4.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

4.9. Quantification of Plasma 11-Ketotestosterone (ELISA)

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andreu-Vieyra, C.V.; Buret, A.G.; Habibi, H.R. Gronadotropin-releasing hormone induction of apoptosis in the testes of goldfish (Caraasius auratus). Endocrinology 2005, 146, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, D.; Assis, L.H.; Zhang, Y.T.; Safian, D.; Furmanek, T.; Skaftnesmo, K.O.; Norberg, B.; Ge, W.; Choi, Y.C.; den Broeder, M.J.; et al. Insulin-like 3 affects zebrafish spermatogenic cells directly and via Sertoli cells. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.S.; Jiao, B.; Hu, C.; Huang, X.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, C.H.K. Discovery of a gonad-specific IGF subtype in teleost. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 367, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Nóbrega, R.; Pšenička, M. Spermatogonial stem cells in fish: Characterization, isolation, enrichment, and recent advances of in vitro culture systems. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doretto, L.B.; Butzge, A.J.; Nakajima, R.T.; Martinez, E.R.; de Souza, B.M.; Rodrigues, M.D.S.; Rosa, I.F.; Ricci, J.M.; Tovo-Neto, A.; Costa, D.F.; et al. Gdnf Acts as a Germ Cell-Derived Growth Factor and Regulates the Zebrafish Germ Stem Cell Niche in Autocrine- and Paracrine-Dependent Manners. Cells 2022, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, H.R.; Andreu-Vieyra, C.V. Hormonal regulation of follicular atresia in teleost fish. In The Fish Oocyte: From Basic Studies to Biotechnological Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, Y.; Habas, R. Wnt Secretion and Extra-Cellular Regulators. Organogenesis 2008, 4, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, R.H.; Morais, R.D.V.D.S.; Crespo, D.; De Waal, P.P.; De França, L.R.; Schulz, R.W.; Bogerd, J. Fsh stimulates spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation in zebrafish via Igf3. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 3804–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, D.; Habibi, H.R. Direct action of GnRH variants on goldfish oocyte meiosis and follicular steroidogenesis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000, 160, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.; Zanuy, S.; Gómez, A. Conserved anti-müllerian hormone: Anti-müllerian hormone type-2 receptor specific interaction and intracellular signaling in teleosts. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, D.; Assis, L.H.; Van De Kant, H.J.; De Waard, S.; Safian, D.; Lemos, M.S.; Bogerd, J.; Schulz, R.W. Endocrine and local signaling interact to regulate spermatogenesis in zebrafish: Follicle-stimulating hormone, retinoic acid and androgens. Development 2019, 146, dev178665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KSkaar, S.; Nóbrega, R.H.; Magaraki, A.; Olsen, L.C.; Schulz, R.W.; Male, R. Proteolytically activated, recombinant anti-Müllerian hormone inhibits androgen secretion, proliferation, and differentiation of spermatogonia in adult zebrafish testis organ cultures. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3527–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, H.P.; Tovo-Neto, A.; Yeung, E.C.; Nóbrega, R.H.; Habibi, H.R. Paracrine/autocrine control of spermatogenesis by gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 492, 110440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, H.P.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Zanardini, M.; Nóbrega, R.H.; Habibi, H.R. Effects of gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone on early and late stages of spermatogenesis in ex-vivo culture of zebrafish testis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 520, 111087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, H.P.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Corchuelo, S.; Nóbrega, R.H.; Habibi, H.R. Role of GnRH Isoforms in Paracrine/Autocrine Control of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, K.P.; Chaube, R. Vasotocin—A new player in the control of oocyte maturation and ovulation in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2015, 221, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennigen, J.A.; Ramachandran, D.; Shaw, K.; Chaube, R.; Joy, K.P.; Trudeau, V.L. Reproductive roles of the vasopressin/oxytocin neuropeptide family in teleost fishes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1005863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanardini, M.; Zhang, W.; Habibi, H.R. Arginine Vasotocin Directly Regulates Spermatogenesis in Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Testes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, D.; Sharma, K.; Saxena, V.; Nipu, N.; Rajapaksha, D.C.; Mennigen, J.A. Knock-out of vasotocin reduces reproductive success in female zebrafish, Danio rerio. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1151299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Chaube, R.; Joy, K.P. Vasotocin stimulates maturation-inducing hormone, oocyte maturation and ovulation in the catfish Heteropneustes fossilis: Evidence for a preferential calcium involvement. Theriogenology 2021, 167, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Joy, K.P. Effects of hCG and ovarian steroid hormones on vasotocin levels in the female catfish Heteropneustes fossilis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2009, 162, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Joy, K.P. An involvement of vasotocin in oocyte hydration in the catfish Heteropneustes fossilis: A comparison with effects of isotocin and hCG. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 166, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, A.; Chauvigné, F.; Gozdowska, M.; Kulczykowska, E.; Finn, R.N.; Cerdà, J. Neurohypophysial and paracrine vasopressinergic signaling regulates aquaporin trafficking to hydrate marine teleost oocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1222724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanardini, M.; Habibi, H.R. The Role of Neurohypophysial Hormones in the Endocrine and Paracrine Control of Gametogenesis in Fish. Cells 2025, 14, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.M.; Goodson, J.L. Behavioral relevance of species-specific vasotocin anatomy in gregarious finches. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, J.L. Nonapeptides and the evolutionary patterning of sociality. Prog. Brain Res. 2008, 170, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, N.; Bass, A.H. Individual behavioral and neuronal phenotypes for arginine vasotocin mediated courtship and aggression in a territorial teleost. Brain Behav. Evol. 2010, 75, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, J.; Thompson, R. Nonapeptides and Social Behavior in Fishes. Horm. Behav. 2012, 61, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.C.; Paitio, J.R.; Oliveira, R.F.; Bshary, R.; Soares, M.C. Arginine vasotocin reduces levels of cooperative behaviour in a cleaner fish. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 139, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmieme, Z.; Jubouri, M.; Touma, K.; Coté, G.; Fonseca, M.; Julian, T.; Mennigen, J.A. A reproductive role for the nonapeptides vasotocin and isotocin in male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 238, 110333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramallo, M.R.; Grober, M.; Cánepa, M.M.; Morandini, L.; Pandolfi, M. Arginine-vasotocin expression and participation in reproduction and social behavior in males of the cichlid fish Cichlasoma dimerus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2012, 179, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lema, S.C.; Sanders, K.E.; Walti, K.A. Arginine Vasotocin, Isotocin and Nonapeptide Receptor Gene Expression Link to Social Status and Aggression in Sex-Dependent Patterns. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 27, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozdowska, M.; Kleszczyńska, A.; Sokołowska, E.; Kulczykowska, E. Arginine vasotocin (AVT) and isotocin (IT) in fish brain: Diurnal and seasonal variations. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 143, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karigo, T.; Kanda, S.; Takahashi, A.; Abe, H.; Okubo, K.; Oka, Y. Time-of-Day-Dependent Changes in GnRH1 Neuronal Activities and Gonadotropin mRNA Expression in a Daily Spawning Fish, Medaka. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3394–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balment, R.J.; Lu, W.; Weybourne, E.; Warne, J.M. Arginine vasotocin a key hormone in fish physiology and behaviour: A review with insights from mammalian models. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 147, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Illamola, A.; Patiño, M.A.L.; Soengas, J.L.; Ceinos, R.M.; Míguez, J.M. Diurnal rhythms in hypothalamic/pituitary AVT synthesis and secretion in rainbow trout: Evidence for a circadian regulation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 170, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, T.; Swaney, W.T.; Reddon, A.R. Dominance and aggressiveness are associated with vasotocin neuron numbers in a cooperatively breeding cichlid fish. Horm. Behav. 2024, 168, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Kline, R.J.; Vázquez, O.A.; Khan, I.A.; Thomas, P. Molecular characterization and expression of arginine vasotocin V1a2 receptor in Atlantic croaker brain: Potential mechanisms of its downregulation by PCB77. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, A.K.; Wark, A.R.; Fernald, R.D.; Hofmann, H.A. Expression of arginine vasotocin in distinct preoptic regions is associated with dominant and subordinate behaviour in an African cichlid fish. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 2393–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardini, M.; Parker, N.; Ma, Y.; Habibi, H.R. Arginine vasotocin is a player in the multifactorial control of spermatogenesis in zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1672823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, E.; Gozdowska, M.; Kulczykowska, E. Nonapeptides Arginine Vasotocin and Isotocin in Fishes: Advantage of Bioactive Molecules Measurement. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Chaube, R.; Joy, K.P. In situ localization of vasotocin receptor gene transcripts in the brain-pituitary-gonadal axis of the catfish Heteropneustes fossilis: A morpho-functional study. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofanopoulou, C.; Gedman, G.; Cahill, J.A.; Boeckx, C.; Jarvis, E.D. Universal nomenclature for oxytocin–vasotocin ligand and receptor families. Nature 2021, 592, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.S.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H.; You, Y.A.; Kim, I.C.; Pang, M.G. Vasopressin Effectively Suppresses Male Fertility. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Fujinoki, M.; Azuma, M.; Koshimizu, T. Vasopressin V1a receptor and oxytocin receptor regulate murine sperm motility differently. Life Sci. Alliance 2023, 6, e202201488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, G.L.; Hammes, T.O.; Escobar, T.D.C.; Fracasso, L.B.; Forgiarini, L.F.; da Silveira, T.R. Blood Collection for Biochemical Analysis in Adult Zebrafish. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 26, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerfield, M. The zebrafish book. In A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), 4th ed.; University of Oregon Press: Eugene, OR, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Avdesh, A.; Chen, M.; Martin-Iverson, M.T.; Mondal, A.; Ong, D.; Rainey-Smith, S.; Taddei, K.; Lardelli, M.; Groth, D.M.; Verdile, G.; et al. Regular Care and Maintenance of a Zebrafish Laboratory: An Introduction. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 69, e4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, K.O.; Harris, W.A. Characterization and Development of Courtship in Zebrafish, Danio rerio. Zebrafish 2004, 1, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2019, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thisse, C.; Thisse, B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeswari, J.J.; Gilbert, G.N.Y.; Khalid, E.; Vijayan, M.M. Brain monoamine changes modulate the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1-mediated behavioural response to acute thermal stress in zebrafish larvae. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2025, 600, 112494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, K.; Lu, C.; Liu, X.; Trudeau, V.L. Arginine vasopressin injection rescues delayed oviposition in cyp19a1b-/- mutant female zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1308675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toni, L.S.; Garcia, A.M.; Jeffrey, D.A.; Jiang, X.; Stauffer, B.L.; Miyamoto, S.D.; Sucharov, C.C. Optimization of phenol-chloroform RNA extraction. MethodsX 2018, 5, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Probe | Primer Combination | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Sense avt | T7-FW + RV | 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGTCAGACTCTCTGCTGTCT + TAGGCGATGTGTTCAGAAAGG-3′ |

| Antisense avt | FW + T7-RV | 5′–TGTCAGACTCTCTGCTGTCT + TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTAGGCGATGTGTTCAGAAAGG-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zanardini, M.; Habibi, H.R. Integrated Role of Arginine Vasotocin in the Control of Spermatogenesis in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411938

Zanardini M, Habibi HR. Integrated Role of Arginine Vasotocin in the Control of Spermatogenesis in Zebrafish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411938

Chicago/Turabian StyleZanardini, Maya, and Hamid R. Habibi. 2025. "Integrated Role of Arginine Vasotocin in the Control of Spermatogenesis in Zebrafish" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411938

APA StyleZanardini, M., & Habibi, H. R. (2025). Integrated Role of Arginine Vasotocin in the Control of Spermatogenesis in Zebrafish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411938